Abstract

The present research used the cluster analysis method to examine the acculturation of immigrant Chinese mothers (ICMs), and the demographic characteristics and psychological functioning associated with each acculturation style. The sample was comprised of 83 first-generation ICMs of preschool children residing in Maryland, Unites States (US). Cluster analysis revealed four acculturation styles: psychologically-behaviorally integrated; psychologically-behaviorally assimilated; psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated; and psychologically-behaviorally separated. Assimilated mothers were the youngest at immigration and had resided in the US for the longest time. Separated mothers were older at immigration, resided in the US for a shorter time, were less educated, and had lower psychological functioning than mothers in the other clusters. However, there were no differences in demographic characteristics and psychological functioning between psychologically-behaviorally integrated and psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated clusters. The importance of simultaneously assessing various cultural orientations and components of acculturation was highlighted.

Keywords: acculturation, immigrant Chinese, parents, psychological functioning

Immigrants face many stressors after arriving in a new country, and are at risk for poor psychological outcomes. However, research is inconsistent regarding which acculturation style is most associated with immigrants’ healthy psychological functioning. Another limitation of the acculturation literature pertains to its measurement. Most researchers adopt a categorical approach, using cutoff scores to assign individuals to different acculturation styles (Chia & Costigan, 2006). However, acculturation operates on a continuum (Roysircar-Sodowsky & Maestas, 2000), and such approaches do not effectively capture the multidimensional nature of acculturation.

Although Asian-Americans are perceived to experience low rates of psychopathology, more recent clinical studies clearly indicate a higher prevalence than previously thought (Durvasula & Sue, 1996; Shen, Alden, Sochting, & Tsang, 2006). Further, when Asian-Americans do seek mental health services, they are more impaired than patients from other cultural backgrounds (Surgeon General, US Public Health Services Office of the Surgeon General, 1999). However, the model minority stereotype, or the perception that certain immigrant groups experience successful adaptation without social or psychological problems (Lee, 1996), has resulted in little empirical examination of factors associated with psychological outcomes in immigrant Asian-American families, such as acculturation.

We examined the role of acculturation in the psychological functioning of immigrant Chinese mothers (ICMs) of young children for several reasons. First, Chinese individuals are more interdependent and tend to view the self as connected to others and maintain social relationships (Triandis, 2001). Within the more independent culture of the United States, Chinese immigrants may face greater cultural distance during the acculturation process, which may place them at risk for acculturative stress (Berry, Kim, Minde, & Mok, 1987) and poor adjustment (e.g., Hwang, Chun, Takeuchi, Myers, & Siddarth, 2005).

Additionally, immigrant men and women experience acculturation differently due to gender role socialization (Berry & Sam, 1997). Asian immigrant mothers are more traditional in their child-rearing than other groups (Bornstein & Cote, 2006), perhaps in an attempt to pass on cultural values and practices to their children. Moreover, during the preschool period, mothers interact more with the larger community (i.e., school, child's peers and their parents), and experience a heightened, self-conscious period of parental socialization (Olson, Kashiwagi, & Crystal, 2001). Thus, mothers’ acculturation can significantly impact their psychological functioning (Hwang et al., 2005) and parenting practices (e.g., Dix, Cheng, & Day, 2008). Last, first-generation ICMs were examined because acculturation is more readily visible among first-generation immigrants (Portes & Rumbaut, 1996). The present study specifically examined ICMs residing in Maryland communities.

The present research had three goals: (1) to adopt a multidimensional approach to examine acculturation using the cluster analysis technique (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984), which utilized mothers’ pattern of responses to four acculturation measures to determine the acculturation clusters that existed among the sample; (2) to examine specific demographic factors associated with membership in each acculturation cluster; and (3) to examine differences in the psychological functioning of ICMs across these clusters.

Acculturation

The predominant theory of acculturation conceptualizes four acculturation styles resulting from the ways in which immigrants balance their orientation toward their culture of heritage and the host culture (Berry, 1980, 2006). The integrated style of acculturation occurs when individuals maintain their heritage culture as well as interact with the host culture. In contrast, the marginalized style refers to those individuals who reject both their heritage and host cultures. Assimilated individuals seek out the host culture, leaving their heritage culture behind, whereas separated individuals maintain their heritage culture and disregard the host culture (Berry, 2006).

Acculturation components

The acculturation process can be further distinguished into two components. First, behavioral acculturation refers to the individual's participation in the observable and external aspects of American and Chinese cultures, and reflects his/her ability to fit in behaviorally with a new sociocultural setting and/or maintain his/her heritage culture's practices. Second, psychological acculturation refers to the individual's identification with the values, norms, beliefs, and attitudes of the host or heritage cultures (Berry, 1992; Searle & Ward, 1990).

Although sometimes related, behavioral and psychological acculturation have been shown to be distinct processes (Birman, 2006; Phinney, 1995), associated with different adjustment outcomes (Birman & Tran, 2008), and predicted by different demographic variables (Mariño, Stuart, & Minas, 2000). Psychological acculturation is important to examine among immigrant Chinese families because traditional values and beliefs are particularly salient for Asian-Americans’ identity formation (Phinney, 1990) and are often maintained during the acculturation process (Chun & Akutsu, 2003). However, the unique role of psychological acculturation in the psychological functioning of ICMs has been ignored. The present study examined the unique associations between psychological and behavioral acculturation, and psychological functioning.

Additionally, double-barreled items are often used to measure both dimensions of acculturation, which forces participants to favor one dimension over the other (e.g., the host over the heritage culture; Nguyen, Messe, & Stollak, 1999). To address this limitation, some researchers create separate scales for each dimension and utilize cut-off scores based on the mean or median to group participants into Berry's (1980) four styles. However, this method is also problematic because: (1) researchers often vary in the type of cut-off score utilized (i.e., mean or median); (2) individuals are categorized based on a single score representing their acculturation style; and (3) the data are split into acculturation groups in samples where such heterogeneity may not exist (Arends-Toth & van de Vijver, 2006). Thus, acculturation is treated as a dichotomous variable and sample variance is ignored, potentially mislabeling the acculturation patterns that may exist in immigrant samples.

To address these limitations, our first goal was to adopt a multidimensional approach to create the acculturation styles by using cluster-analysis statistics (Anderberg, 1975). This statistical method creates clusters of individuals based on the pattern of their responses to several different items across a variety of variables (Bergman & Magnusson, 1997). Instead of dichotomizing acculturation by creating groups based on cut-off scores, the cluster-analysis method treats acculturation as a continuous variable and provides insight about the variance that exists in the sample. We utilized this technique to examine mothers’ pattern of responses across four acculturation scales, thereby allowing the simultaneous assessment of mothers’ behavioral and psychological acculturation to both the heritage and the host cultures. The resulting clusters served as the acculturation styles used in subsequent analyses.

Demographic profile of acculturation styles

Our second goal was to examine how various demographic descriptors differed based on mothers’ acculturation style. The notion of acculturation conditions refers to the acculturation context and factors within the individual or setting that influence the acculturation process, such as age and education level (Bourhis, Moïse, Perreault, & Senécal, 1997).

Younger age at immigration and greater length of residence are associated with immigrants’ endorsement of the integrated and assimilated acculturation styles (Lee, Sobal, & Frongillo, 2003). Over time, immigrants are more exposed to the values or behaviors of the host culture, which contributes to their endorsement of the integrated and assimilated styles (Ryder, Alden, & Paulhus, 2000). Moreover, higher education and income levels are positively related to the integrated acculturation style due to greater likelihood of interactions with the host culture (Garcia Coll et al., 2002).

Thus, we explored if the following demographic variables were concurrently related to ICMs’ acculturation style: age at immigration, length of residence in the United States (US), and educational attainment. We predicted that younger age at immigration, longer period of residence in the US, and higher levels of maternal education would be associated with the integrated and assimilated acculturative styles.

Psychological functioning

Our third goal was to examine the psychological functioning of ICMs with different acculturation styles. Recent research indicates that integrated immigrants in many countries have better overall health than assimilated, separated, and marginalized immigrants (e.g., Berry, 2006; Phinney, Horenczyk, Liebkind, & Vedder, 2001). Specifically, Chinese immigrants with social networks comprised of both Chinese and non-Chinese members, and who participate in both Chinese and American activities, reported greater life satisfaction and reduced psychological problems (Ying, 1996). The ability to adapt to both cultures may result in greater cognitive functioning, coping responses, and subsequent mental health.

However, the benefits of the integrated style are less known if we tease apart the behavioral and psychological components. Most researchers assess only the behavioral component of acculturation, using items such as English fluency (e.g., Laroche, Kim, Hui, & Joy, 1996). Moreover, the association between psychological acculturation and well-being may vary depending on whether the host or heritage culture is being examined. Indeed, psychological acculturation towards one's heritage culture and behavioral acculturation towards the host culture are predictive of positive well-being (Birman & Tran, 2008). Immigrants who maintain their traditional values but also participate in American culture appear to have positive psychological functioning.

Researchers also tend to focus on negative outcomes associated with acculturation, such as acculturative stress and depression. However, behavioral acculturation is also predictive of greater self-esteem among Chinese immigrants (Schnittker, 2002). Thus, we examined both positive psychological well-being and depressive symptoms.

As discussed, the integrated acculturation style appears to be associated with positive psychological outcomes. Due to strong ethnic identity among Asian immigrants, ICMs’ identification with and participation in both heritage and host cultures may be salient for their psychological functioning. We expected that integrated ICMs would have greater mean levels of psychological well-being and lower levels of depressive symptoms than those who endorsed other acculturation styles, particularly marginalized ICMs who did not identify with or have access to resources from either host or heritage cultures.

Method

Participants

Eighty-three first-generation married Chinese mothers (M = 37.48 years, SD = 4.04) with a preschool-aged child (M = 4.23 years, SD = .83) participated in the present study. Almost all the mothers had a Bachelor's degree or higher (93.1%), and 2.4% had secondary school education only. Mothers were originally from mainland China (67.5%), Taiwan (24.1%), Hong Kong (6.0%), or other Asian country (2.4%), and had been in the US for 10.51 years (SD = 7.62) on average (4 months to 45.25 years). On average, mothers migrated to the US at 27.13 years of age (SD = 7.38). Reasons for migration included education (32.5%), marriage/came with spouse (25.3%), reunion with family in US (9.6%), better living opportunities (9.6%), employment (7.2%), and political reasons (2.4%). Most mothers had more than one child (43.8% had one child, 41.1% had two children, 13.8% had three children, and 1.3% had four children).

Procedure

The present research utilized data collected at the first wave of a larger longitudinal study examining the parenting and social-emotional development of immigrant Chinese parents with preschool-aged children. Participants were recruited from Chinese organizations, schools, and churches throughout Maryland, US. Data collection was conducted during a home visit by two trained research assistants who were fluent in the preferred language or dialect (English, Mandarin, or Cantonese). After providing written consent, mothers completed the questionnaires in the language of their preference: 26 in English, 52 in simplified Chinese, and five in traditional Chinese. No differences were found between mothers who chose one language over the other. Participants received $40 and project newsletters for their time.

Measures

Several measures were translated from the English language to Chinese using an extensive translation and back-translation process as recommended by Pena (2007).

Demographics

The Family Description Measure was used to obtain demographic information about the mother's age, employment, education, and nationality (Bornstein, 1991). Mothers also reported their length of residence in the US (in years). Maternal age at immigration was calculated from mothers’ current age and length of residence.

Psychological acculturation to American culture

The European-American Values Scale for Asian-Americans—Revised (EAVS-AA-R; Hong, Kim, & Wolfe, 2005) assessed participants’ identification with European-American values regarding child-rearing, marital behavior, autonomy, sexual freedom, career, and friendships, on a scale of “1” (strongly disagree) to “4” (strongly agree). The 25 items were summed to create a score for overall psychological acculturation to American values (sample item: “The world would be a better place if each individual could maximize his or her development”). Fair internal consistency and good divergent validity for this measure (e.g., Park & Kim, 2008) have been demonstrated. For the present sample, α = .65.

Psychological acculturation to Chinese culture

The Asian-American Values Scale—Revised (AAVS-R; Kim & Hong, 2004) assessed participants’ identification with Chinese values regarding filial piety, conformity, hierarchical family structure, humility, collectivism, emotional restraint, and respect for authority, on a scale of “1” (strongly disagree) to “4” (strongly agree). This 25-item scale was summed to create an overall score for psychological acculturation to Chinese values (sample item: “One should be humble and modest”). The AAVS-R has demonstrated good psychometric properties across Chinese samples (Iwamoto, 2008; Trinh, Rho, Lu, & Sanders, 2009). In the present sample, α = .74.

Behavioral acculturation to Chinese and American cultures

Mothers’ behavioral acculturation was measured using the Chinese Parent Acculturation Scale (CPAS; Lee, 1996). The scale is comprised of items regarding participants’ active participation in Chinese culture and American culture across three domains: social activities, language proficiency, and lifestyle. A sample item for social activities includes, “How often do you spend time with your Chinese (non-Chinese) friends?” with a rating scale of “1” (almost never) to “5” (more than once a week). A sample item for language use/proficiency includes, “How well do you speak Chinese (English)?” using a rating scale of “1” (extremely poor) to “5” (extremely well). An example item for lifestyle includes, “Do you celebrate Chinese festivals, such as Chinese New Year, Mid-Autumn Festival, etc. (American holidays)?” using a rating scale of “1” (not at all) to “5” (very much). In the present sample, α = .73 and .78, for the Chinese and American factors, respectively.

Psychological functioning

Depressive symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is comprised of 21 items assessing somatic, affective, and behavioral aspects of depression. A sample item includes, “I feel sad” using a scale of “0” (I do not feel sad), “1” (I feel sad much of the time), “2” (I am sad all the time), and “3” (I am so sad that I can't stand it). The BDI-II has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in Chinese samples (Leong, Okazaki, & Tak, 2003; Shek, 1991). For the present sample, α = .85.

Positive psychological functioning

The Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWBS; Ryff, 1995) was administered to assess mothers’ positive psychological functioning across six dimensions of functioning (e.g., autonomy, environmental mastery, self-acceptance, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life) on a scale of “1” (strongly disagree) to “7” (strongly agree). The items were summed to create an overall well-being score (sample item, “I am quite good at mastering the many responsibilities of my daily life”). The PWBS has demonstrated good psychometric properties in diverse samples (Downie et al., 2007; Iwamoto, 2008). For the present sample, α = .83.

Results

First, outliers and missing data were examined. The univariate and bivariate distributions of the predictors and outcomes were analyzed, which revealed very few cases as potential outliers. Moreover, these cases were not influential on the predictors because they were close to the mean on each predictor, and were therefore included in the analyses. Also, three cases had missing data on a majority of the measures and were removed from the analyses. The mean substitution method was utilized for any of the outcome measures that had minimal missing data. Three cases were missing data on the age at immigration variable and were removed using the pair-wise deletion process.

Aims 1 and 2: Identifying acculturation clusters and associated demographic profiles

The hierarchical clustering method, which does not require a preset number of clusters, was used in the present study (Borgen & Barnett, 1987), and allowed for the exploration of acculturation styles that may exist in our sample in addition to those specified by Berry's (1980) model. Ward's (1963) method is designed to optimize the minimum amount of variance within clusters by combining those entities that have the smallest squared Euclidean distance between them (Borgen & Barnett, 1987). The following acculturation variables were submitted to Ward's (1963) method: (1) behavioral acculturation to American culture (behavioral-American); (2) behavioral acculturation to Chinese culture (behavioral-Chinese); (3) psychological acculturation to American culture (psychological-American); and (4) psychological acculturation to Chinese culture (psychological-Chinese). The four acculturation measures were standardized prior to conducting the cluster analyses due to differences in the scale responses and number of items between the four factors.

Next, we applied three strategies to determine the optimal number of clusters that should be retained: (1) interpretation of the dendogram (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984); (2) application of Mojena's Rule One (Lorr, 1983); and (3) an examination of the fusion coefficients (Milligan & Cooper, 1985). From these three strategies, the four-cluster solution was deemed the most optimal solution and was retained as a grouping variable for all subsequent analyses.1

Importantly, cluster 2 contained only five participants. However, given the limited amount of research on this sample of mothers and that retaining cluster 2 for this specific set of analyses aided in our understanding of the relative makeup of each cluster, cluster 2 was retained for follow-up analyses in aim 1 (labeling of each cluster) and aim 2 (demographic profiles), but not in aim 3 (psychological functioning). Resulting limitations are presented in the Discussion.

Four strategies were utilized to describe the clusters (Chia & Costigan, 2006). First, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed using the four acculturation factors as dependent variables and the cluster groups as independent variables. The MANOVA revealed a significant multivariate effect, F(12, 234) = 16.81, p < .001, which was accounted for by significant univariate effects on all four acculturation factors: psychological-Chinese, F(3, 79) = 2.97, p < .001, f = .33; psychological-American, F(3, 79) = 3.90, p < .001, f = .39; behavioral-Chinese, F(3, 79) = 4.58, p < .001, f = .41; and behavioral-American, F(3, 79) = 6.05, p < .001, f = .48.

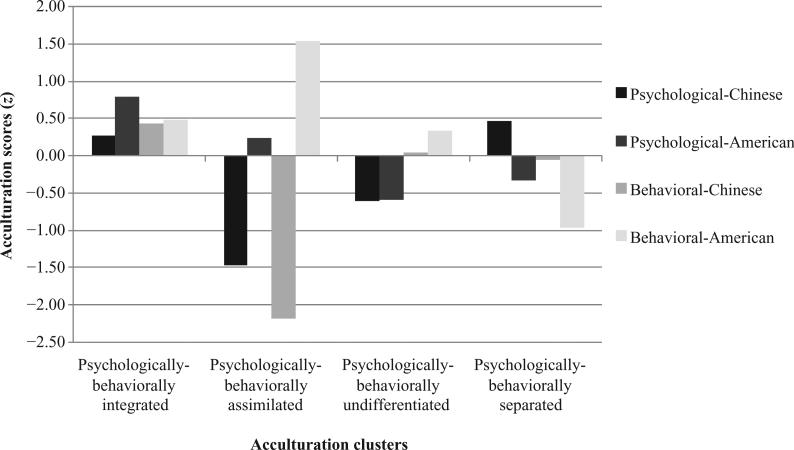

Second, four one-way between-group analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were utilized to test mean differences between the clusters on the four acculturation factors. Third, independent samples t-tests were employed to examine whether the clusters’ means differed from the sample mean within each acculturation factor. Finally, univariate ANOVAs were used to examine the demographic profiles of mothers in each cluster (chi-square analyses were utilized for analyses regarding educational attainment only). The findings from these univariate analyses are presented in Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 1, and the description of each of the clusters are presented in the following sections.

Table 1.

Mean differences between the four acculturation clusters

| Psychologically-behaviorally integrated (cluster 1) (N = 27) M (SD) | Psychologically-behaviorally assimilated (cluster 2) (N = 5) M (SD) | Psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated (cluster 3) (N = 22) M (SD) | Psychologically-behaviorally separated (cluster 4) (N = 29) M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological-American | 36.59 (3.95) | 34.00 (4.30) | 30.14 (3.83) | 31.38 (3.62) |

| F(3, 79) = 13.90, p < .001, f = .71 | ||||

| Sample mean | 32.90 (4.64) | 32.90 (4.64) | 32.90 (4.64) | 32.90 (4.64) |

| t = 4.85*** | t = 0.57 | t = –3.39** | t = –2.28* | |

| f2 = .90 | f2 = .08 | f2 = .55 | f2 = .19 | |

| Psychological-Chinese | 63.70 (4.49) | 52.80 (5.40) | 58.27 (6.06) | 64.97 (5.17) |

| F(3, 79) = 12.97, p < .001, f = .67 | ||||

| Sample mean | 62.05 (6.26) | 62.05 (6.26) | 62.05 (6.26) | 62.05 (6.26) |

| t = 1.92 | t = –3.83* | t = –2.93** | – = 3.04** | |

| f2 = .14 | f2 = 3.67 | f2 = .41 | f2 = .19 | |

| Behavioral-American | 31.93 (4.28) | 38.20 (3.90) | 31.00 (3.13) | 23.28 (4.20) |

| F(3, 79) = 36.05, p < .001, f = 1.15 | ||||

| Sample mean | 29.04 (5.98) | 29.04 (5.98) | 29.04 (5.98) | 29.04 (5.98) |

| t = 3.51** | t = 5.25** | t = 2.94** | t = –7.39*** | |

| f2 = .47 | f2 = 6.89 | f2 = .41 | f2 = 1.95 | |

| Behavioral-Chinese | 42.82 (6.83) | 25.20 (1.64) | 40.23 (2.67) | 39.52 (5.99) |

| F(3, 79) = 14.58, p < .001, f = .72 | ||||

| Sample mean | 32.92 (6.71) | 32.92 (6.71) | 32.92 (6.71) | 32.92 (6.71) |

| t = 2.20* | t = –20.03*** | t = 0.54 | t = –0.36 | |

| f2 = .19 | f2 = 100.30 | f2 = .01 | f2 = .01 | |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Table 2.

Mean differences between acculturation clusters on demographic characteristics and psychological functioning

| Psychologically-behaviorally integrated (cluster 1) (N = 27) M (SD) | Psychologically-behaviorally assimilated (cluster 2) (N = 5) M (SD) | Psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated (cluster 3) (N = 22) M (SD) | Psychologically-behaviorally separated (cluster 4) (N = 29) M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at immigration (years) | 25.71 (5.35) | 9.27 (10.46) | 29.47 (5.13) | 30.05 (4.80) |

| F(3, 76) = 21.84, p < .01; f = .91 | ||||

| Maternal education | ||||

| Bachelor's degree | 5.0 (19%) | — | 5.0 (25%) | 14.0 (54%) |

| Graduate degree | 21.0 (81%) | 15.0 (75%) | 12.0 (46%) | |

| χ2 (2, N = 72) = 7.88, p < .05; ϕ = .33 | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | 5.26 (6.53) | — | 4.23 (5.82) | 8.29 (6.47) |

| F(2,74) = 3.02, p < .05, f = .28 | ||||

| Psychological well-being | 85.30 (10.42) | — | 86.82 (7.20) | 76.41 (9.67) |

| F(2, 75) = 9.73, p < .001, f = .50 | ||||

*p < .05

**p < .01

***p < .001.

Figure 1.

Four-cluster solution of the acculturation clusters.

Cluster 1 (N = 27; 33% of the sample)

Mothers in cluster 1 scored significantly higher on psychological-American than clusters 3 and 4 and the sample mean. Cluster 1 also scored higher on psychological-Chinese compared to clusters 2 and 3. However, cluster 1's mean level on psychological-Chinese was not statistically different from the sample mean. Regarding their behavioral acculturation-American, cluster 1 mothers scored significantly higher than cluster 4 but lower than cluster 2, and higher than the sample mean. Additionally, cluster 1 scored significantly higher than cluster 2 and the sample mean on behavioral-Chinese. Thus, because cluster 1 was higher on both American and Chinese psychological and behavioral orientations than other clusters, it was labeled “psychologically and behaviorally integrated” (psychologically-behaviorally integrated).

Cluster 1 mothers were significantly older at immigration and had lived in the US for a shorter amount of time than cluster 2 (psychologically-behaviorally assimilated) mothers. Cluster 1 mothers were younger but significantly more likely to have a graduate degree than cluster 4 (psychologically-behaviorally separated) mothers.

Cluster 2 (N = 5; 6% of the sample)

Cluster 2 was the smallest in the sample. Cluster 2 mothers scored significantly lower than Cluster 1 and 4 mothers and the sample mean on psychological-Chinese. Additionally, they did not score differently than the other clusters or the psychological-American sample mean. Regarding their behavioral acculturation, cluster 2 mothers scored the highest of all the clusters and significantly higher than the sample mean on behavioral-American. Follow-up paired t-tests indicated that cluster 2 mothers’ behavioral-American scores were significantly greater than their behavioral-Chinese scores, t(4) 6.58, p < .008, d = 3.08. Additionally, cluster 2 mothers scored significantly lower than the other clusters and lower than the sample mean on behavioral-Chinese. Thus, with lower scores on the Chinese psychological and behavioral orientation and higher scores on the American psychological and behavioral orientation than the rest of the sample, cluster 2 was labeled “psychologically and behaviorally assimilated” (psychologically-behaviorally assimilated).

As expected, cluster 2 mothers were the youngest during immigration to the US and had the longest US residence of all the clusters. The small sample size of this cluster prevented its inclusion in the chi-square analyses comparing mothers’ level of educational attainment.

Cluster 3 (N = 22; 27% of the sample)

Mothers in cluster 3 scored significantly lower than those in cluster 1, but were not significantly different from the other two clusters on psychological-American. Also, mothers’ psychological-American scores were lower than the sample mean. Cluster 3 mothers scored lower than those in clusters 1 and 4 and the sample mean on psychological-Chinese. Regarding their behavioral acculturation, cluster 3 mothers scored significantly lower than cluster 2, but higher than cluster 4 and the sample mean on behavioral-American. These mothers did not differ from those in cluster 1 on this factor. Additionally, cluster 3 mothers scored significantly higher than those in cluster 2 on behavioral-Chinese, but did not differ from the sample mean or the other clusters on this factor. Thus, cluster 3 mothers were not consistently different from the other clusters on psychological acculturation to both cultural orientations (i.e., psychological-American and psychological-Chinese). Although these mothers scored lower than the sample means, their scores were not extremely low, indicating partial endorsement of the values of both cultures. Additionally, cluster 3 mothers’ behavioral acculturation scores did not follow a pattern that was consistent with Berry's styles. Therefore this cluster was labeled “psychologically and behaviorally undifferentiated” (psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated).

Cluster 3 mothers were significantly older at immigration and had lived in the US for a shorter amount of time than cluster 2 (psychologically-behaviorally assimilated) mothers. However, these mothers did not differ from cluster 1 (psychologically-behaviorally integrated) and cluster 4 (psychologically-behaviorally separated) on age at immigration and length of residence in the US. A significantly greater proportion of cluster 3 mothers had a post-baccalaureate degree than cluster 4 (psychologically-behaviorally separated) mothers.

Cluster 4 (N = 29; 35% of the sample)

Mothers in this cluster's score on psychological-American was significantly lower than cluster 1 and the sample mean, and was also lower than their psychological-Chinese, t(28) = –25.96, p < .008, d = –4.87 and behavioral-Chinese, t(28) = –6.03, p < .008, d = –1.15, scores. Additionally, cluster 4 mothers’ scores on psychological-Chinese were significantly higher than clusters 2 and 3, and the sample mean. According to paired t-tests, their psychological-Chinese scores were also higher than their scores on psychological-American, t(28) = 25.96, p < .008, d = 4.87, and behavioral-American, t(28) = 46.59, p < .008, d = 8.78. Regarding their behavioral acculturation, cluster 4 mothers scored significantly lower on behavioral-American than all of the other clusters, the sample mean, and their scores on behavioral-Chinese and psychological-Chinese. Additionally, cluster 4 mothers scored significantly higher than cluster 2 on behavioral-Chinese. Although mothers’ behavioral-Chinese scores did not differ significantly from the sample mean, they scored significantly higher on behavioral-Chinese than on behavioral-American and psychological-American. Thus, because cluster 4 mothers scored lower on the American psychological and behavioral orientations, but higher on the Chinese psychological and behavioral orientations than the rest of the sample, this cluster was labeled “psychologically and behaviorally separated” (psychologically-behaviorally separated).

These mothers were significantly older at immigration than mothers in cluster 1 (psychologically-behaviorally integrated) and cluster 2 (psychologically-behaviorally assimilated), but did not differ from cluster 3 (psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated). Additionally, cluster 4 mothers had not resided in the US as long as mothers in cluster 2 (psychologically-behaviorally assimilated). Finally, these mothers were less educated than cluster 1 (psychologically-behaviorally integrated) and cluster 3 (psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated) mothers.

Aim 3: Psychological functioning

The third aim of the present research was to examine whether the clusters (excluding cluster 2; psychologically-behaviorally assimilated) differed on depressive symptoms and psychological well-being (Table 2).

Depressive symptoms

A one-way between-groups ANOVA indicated significant mean differences between the clusters on depressive symptoms. Cluster 4 (psychologically-behaviorally separated) mothers reported more depressive symptoms than cluster 3 (psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated). There were no differences in depressive symptoms between cluster 1 (psychologically-behaviorally integrated) and cluster 3 (psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated) mothers.

Psychological well-being

A one-way BG ANOVA indicated significant overall effect of psychological well-being. Post-hoc tests demonstrated that cluster 4 (psychologically-behaviorally separated) mothers reported significantly lower psychological well-being, than cluster 1 (psychologically-behaviorally integrated) and cluster 3 (psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated) mothers. There were no differences in overall psychological well-being between cluster 1 (psychologically-behaviorally integrated) and cluster 3 (psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated) mothers.

Discussion

The present study adopted a multidimensional approach to examine acculturation by utilizing cluster analysis statistics. Additionally, we were interested in the demographic profiles and psychological functioning associated with each acculturation style for ICMs of preschool-aged children.

Acculturation styles and demographic profiles

The cluster analysis revealed the presence of four acculturation styles in the present sample. The psychologically-behaviorally integrated, psychologically-behaviorally assimilated, and psychologically-behaviorally separated styles were similar to the acculturation styles outlined by Berry's (1980) model, as well as those found in previous research (e.g., Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006; Chia & Costigan, 2006). However, the fourth style (psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated style) was not represented in Berry's (1980) model.

Consistent with previous research, the psychologically-behaviorally integrated style was one of the most prevalent (33%) and the psychologically-behaviorally assimilated style was the least prevalent style (6%) among ICMs (Chia & Costigan, 2006; Eyou, Adair, & Dixon, 2000). Due to their minority status in a smaller co-ethnic community, these mothers were exposed to the mainstream culture and may have been more likely to endorse these two styles. Asian immigrants’ tendency to maintain their cultural values and behaviors (Chun & Akutsu, 2003) and their first-generation status may explain the much larger number of mothers in the psychologically-behaviorally integrated cluster than in the assimilated cluster.

As expected, these mothers were the youngest at immigration and had resided in the US for a longer period of time than psychologically-behaviorally separated mothers (Lee et al., 2003; Liem, Lim, & Liem, 2000). Additionally, psychologically-behaviorally integrated mothers were more educated than psychologically-behaviorally separated mothers. Frequent exposure to and opportunities for interaction with the host culture within higher-education institutions may contribute to greater integration and assimilation (Ryder et al., 2000). Through such ongoing interactions over time, integrated immigrants are constantly navigating various social arenas and developing different cultural scripts to guide their behaviors in these contexts (Sam & Oppedal, 2003). Given the differences in the demographic descriptors of specific immigrant groups, these factors may play an important role in the acculturation process of each group as they learn a new context, and should be examined in future research.

Consistent with past research, there was also a large group of mothers who endorsed the psychologically-behaviorally separated style of acculturation (35%; Berry et al., 2006; Chia & Costigan, 2006). These mothers were less educated and immigrated to the US at later ages, and may have had less exposure to the host culture, be less receptive to new cultural practices and values, or feel less accepted by the mainstream community. Supporting previous research on Chinese immigrants, mothers in this cluster utilized and relied on resources from their co-ethnic settings (Ward & Lin, 2010). These findings suggest that the demographic variations (i.e., length of residence) may be reflective of different bicultural trajectories as immigrants develop in a new sociocultural setting (Sam & Oppedal, 2003), which may change as the level of acculturative stress varies over time (Ward & Rana-Deuba, 1999). Thus, separated immigrants may become integrated over time. Additionally, separated mothers’ moderate endorsement of Chinese behavioral practices suggests potential flexibility in adapting to alternative cultural behaviors over time. More research is needed to examine the interplay of demographic factors and acculturation trajectories over time.

The fourth acculturation cluster was characterized by a psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated style. Examination of mothers’ overall acculturation as comprised of distinct behavioral and psychological components revealed a style that is inconsistent with Berry's (1980) marginalization style. Regarding their psychological-acculturation, mothers in this group were not particularly low on either the American or Chinese cultural dimension, suggesting that they might endorse some values from each culture, although not particularly strongly, or have a hybrid set of values that are not reflected in either culture separately (Coleman, Casali, & Wampold, 2001). Moreover, these mothers’ inconsistent but moderate identification with cultural values may be reflective of the measures used in the present study. Specifically, the American values scale (i.e., EAVS-AA-R) contained items which are skewed towards controversial topics that may be irrelevant to first-generation ICMs. Psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated mothers also participated in both American and Chinese cultural practices, although at levels that were not consistently higher or lower than the other clusters. Thus, it was difficult to label the behavioral component of acculturation according to Berry's (1980) four styles.

The prevalence of an undifferentiated style suggests that, similar to the “identity confusion” concept in the identity literature, some immigrants have not experienced a sense of clarity in their acculturation style (e.g., Chia & Costigan, 2006; Schwartz & Zamboanga, 2008). Given the rapid Westernization experienced in Asian countries (Chen, Wang, & DeSouza, 2006), mothers’ identification with either culture (i.e., Chinese or American) prior to immigration may influence their acculturation process as they try to navigate the two cultural contexts. These ICMs may still be searching for their place in either culture, behaviorally and psychologically. Thus, by examining the two components of acculturation independently (i.e., behavioral and psychological), we were able to capture the unique experiences of ICMs in the undifferentiated cluster. Importantly, the cluster analysis method allowed for a person-centered approach, which provided a more comprehensive understanding of the multidimensionality of acculturation and the nuances of the acculturation styles of mothers in the sample.

Interestingly, mothers in this cluster presented a generally similar demographic profile than psychologically-behaviorally integrated and separated mothers. Thus, the demographic variables we examined may not have provided sufficient information to distinguish this group from the other groups. Future research should examine other demographic factors that may be important for distinguishing mothers’ categorization in the various acculturation clusters, such as socioeconomic status, country of origin, and the ethnic composition of the neighborhood (Berry & Sam, 1997; Myles & Hou, 2003).

Psychological functioning

As expected, psychologically-behaviorally separated mothers reported lower psychological well-being and more depressive symptoms than psychologically-behaviorally integrated and psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated mothers (Berry, 2006). As psychologically-behaviorally separated mothers were older at immigration and had resided in the US for less time, they may be still navigating through two cultural contexts and experiencing stress (Berry, 2006). Moreover, these mothers may only be able to draw from Chinese cultural resources, which are limited by the smaller size of this community in Maryland. Mothers’ endorsement of the separated style and their lower psychological functioning (i.e., lower well-being and greater depressive symptoms) may influence their childrearing abilities. Poorer psychological functioning may explain the greater endorsement of traditionally controlling parenting behaviors among less acculturated (i.e., separated) mothers (Farver & Lee-Shin, 2000), and subsequently lead to more negative child outcomes.

In contrast, psychologically-behaviorally integrated mothers have the opportunity to draw from both Chinese and American resources, which may help promote greater psychological functioning. In turn, integrated mothers’ positive functioning may be the mechanism through which acculturation is associated with more positive parenting (e.g., Kim & Hong, 2007), and subsequent positive child outcomes. However, more research is needed to examine the potentially mediating role of psychological functioning between acculturation and parenting among immigrant mothers, and child adjustment outcomes.

Interestingly, mothers in the psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated cluster reported greater psychological well-being and less depressive symptoms than those in the psychologically-behaviorally separated cluster, and did not differ from psychologically-behaviorally integrated mothers. Given that undifferentiated immigrants moderately endorse both cultures, they potentially have access to resources from both cultures, which may serve some protective function for these mothers’ psychological functioning, unlike marginalized immigrants who report the poorest psychological functioning of the four styles (e.g., Bornstein & Cote, 2006).

Our findings suggest that the protective functions of various acculturation styles may differ based on immigrants’ behavioral and psychological acculturation patterns. As Asian immigrants face greater dissonance between their traditional and mainstream cultural values compared to other immigrant groups (e.g., East-European immigrants; Triandis, 2001), the function of immigrants’ psychological versus behavioral acculturation may vary across different cultural groups. Although the present research examined positive and negative indicators of psychological functioning, future research should also examine positive and negative indicators of behavioral adaptation (e.g., Berry et al., 2006).

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations of the present research should be noted. First, the small sample size, the lack of variability in the education and socioeconomic levels of the mothers, and the recruitment strategy of the present study limited the exploration of the range of acculturation styles in the sample, and the generalizability of our results. Second, the small sample size of the psychologically-behaviorally assimilated cluster may have impacted the comparisons between the acculturation styles, and limited the number of demographic variables that could be assessed. Recruitment from Chinese organizations may have limited the potential size of the assimilated cluster. Future research should utilize better recruitment methods such as geographic sampling.

Third, our data were self-reported by mothers using a cross-sectional design. Fluctuations in mothers’ identification with and participation in each culture may vary over time and across contexts (Ward & Lin, 2010). Importantly, a cross-sectional design does not allow us to demonstrate directionality between the variables. We proposed that psychologically-behaviorally integrated and assimilated mothers were more highly educated than psychologically-behaviorally separated mothers because frequent exposure to the host culture and higher-education institutions provides greater opportunities for interactions with more European-American-centered environments, contributing to immigrants’ endorsement of these styles. However, mothers who participate more in the American culture may also be more likely to pursue higher education in the new environment. Similarly, although psychologically-behaviorally separated mothers may have poorer psychological functioning because of the lack of resources, mothers with poorer psychological functioning may be less receptive to the mainstream culture. Thus, future research should adopt a longitudinal design to determine temporal precedence among these associations.

Another set of limitations pertains to our interpretation of the four clusters. Following previous research (Chia & Costigan, 2006), and due to the small sample size, a within-sample approach was adopted when describing the clusters. Mothers in each cluster were compared to other mothers in the sample and to the overall sample means on the acculturation measures. For example, mothers in the psychologically-behaviorally undifferentiated cluster were labeled as undifferentiated because they were lower on psychological acculturation to both cultures, relative to the rest of the mothers in the sample; however, their scores may not be very low in absolute terms. Relatedly, the present research tested the clusters on the same variables used to create the clusters, which may have amplified the differences between the clusters (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). Future research should validate the retained cluster solution against: (1) an external set of variables that represent the cultural orientations; and (2) the cluster solution obtained from a similar sample. Last, although the CPAS demonstrated good psychometric properties in the present study, it is not a published scale, which may have impacted the interpretation of the cluster solution. Future research should validate the underlying structure of this measure among samples of ICMs. Moreover, the EAVS-AA-R measure demonstrated poor reliability in the present study, and some of the questions in the scale were worded unclearly and may not assess European-American values (e.g., “Cheating on one's partner does not make a marriage unsuccessful”).

Despite these limitations, the multidimensional approach to examining acculturation offers some advancement in our understanding of the complex nature of acculturation and highlights the diversity that exists among ICMs. Our findings presented a more comprehensive understanding of the acculturation and psychological functioning of ICMs of young children towards the promotion of healthy adaptation in these families. In the examination of the benefits of various acculturation styles, we provided preliminary evidence for the need to consider behavioral and psychological components of acculturation to both the host and heritage cultures, as well the demographic context of immigrants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for their valuable time during the course of the research study. The present study was conducted as a part of the first author's Master's Thesis research.

Funding

This work was supported by the Foundation for Child Development: Changing Faces of America's Children—Young Scholars Program (YSP) and 5 R03 HD052827-02 awarded to the second author.

Footnotes

The dendogram provides a visual representation of the clustering process, as individual cases are combined into clusters. Examination of the dendogram suggested that a three or four cluster solution might be optimal. Second, Mojena's Rule One uses within-cluster variance to determine when a jump in coefficients between stages is too large, which suggests that the larger cluster set from the previous stage is a more optimal solution. Based on the most stringent application of Mojena's rule, the fusion coefficients prior to stage 4 were beyond the acceptable alpha level. This finding indicated greater dissimilarity in the clusters, such that fewer than four clusters should not be retained. Finally, the proportional increase in the fusion coefficients between each stage was examined. These findings suggested relatively insignificant jumps in coefficients from all stages prior to stage four, but indicated a significant jump in cluster dissimilarity at stage three. Thus, based on all three strategies, the four-cluster solution was deemed the most optimal solution.

References

- Aldenderfer MS, Blashfield RK. Cluster analysis. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Anderberg MR. Cluster analysis for applications. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. 1975;17:580–582. [Google Scholar]

- Arends-Toth J, van de Vijver FJR. Issues in the conceptualization and assessment of acculturation. In: Bornstein MH, Cote LR, editors. Acculturation and parent–child relationships. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd ed. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR, Magnusson D. A person oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:291–319. doi: 10.1017/s095457949700206x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In: Padilla A, editor. Acculturation: Theory, models, and findings. Boulder, CO; Westview: 1980. pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation and adaptation in a new society. International Migration Quarterly Review. 1992;30:69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation: A conceptual overview. In: Bornstein MH, Cote LR, editors. Acculturation and parent–child relationships. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Kim U, Minde T, Mok D. Comparative studies of acculturative stress. International Migration Review. 1987;21:491–512. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P. Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2006;55:303–332. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Sam DL. Acculturation and adaptation. In: Berry JW, Segall MH, Kağıtçıbaşı C, editors. Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Vol. 3. Social behavior and applications. 2nd ed. Allyn & Bacon; Boston, MA: 1997. pp. 291–326. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D. Acculturation gap and family adjustment: Findings with Soviet Jewish refugees in the United States and implications for measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2006;37:568–589. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Tran N. Psychological distress and adjustment of Vietnamese refugees in the United States: Association with pre- and postmigration factors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78:109–120. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgen FH, Barnett DC. Applying cluster analysis in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34:456–468. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Approaches to parenting in culture. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Cultural approaches to parenting. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Cote LR. Parenting cognitions and practices in the acculturative process. In: Bornstein MH, Cote LR, editors. Acculturation and parent–child relationships. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bourhis RY, Moïse LC, Perreault S, Senécal S. Towards an interactive acculturation model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology. 1997;32:369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang L, DeSouza A. Temperament, socioemotional functioning, and peer relationships in Chinese and north American children. In: Chen X, French D, Schneider BH, editors. Peer relationships in cultural context. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 123–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chia A-L, Costigan CL. A person-centered approach to identifying acculturation groups among Chinese Canadians. International Journal of Psychology. 2006;41:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Chun KM, Akutsu PD. Acculturation among ethnic minority families. In: Chun K, Balls Organista P, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman HLK, Casali SB, Wampold BE. Adolescent strategies for coping with cultural diversity. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2001;79:356–364. [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Cheng N, Day WH. Connecting with parents: Mothers’ depressive symptoms and responsive behaviors in the regulation of social contact by one- and young two-year-olds. Social Development. 2008;18:24–50. [Google Scholar]

- Downie M, Chua SN, Koestner R, Barrios M-F, Rip B, M'Birkou S. The relations of parental autonomy support to cultural internalization and well-being of immigrants and sojourners. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:241–249. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durvasula R, Sue S. Severity of disturbance among Asian American outpatients. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health. 1996;2:43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyou ML, Adair V, Dixon R. Cultural identity and psychological adjustment of adolescent Chinese immigrants in New Zealand. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23:531–543. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farver JAM, Lee-Shin Y. Acculturation and Korean-American children's social and play behavior. Social Development. 2000;9:316–336. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll CT, Akiba D, Palacios N, Bailey B, Silver R, DiMartino L, Chin C. Parental involvement in children's education: Lessons from three immigrant groups. Parenting Science and Practice. 2002;2:303–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Kim BSK, Wolfe MM. A psychometric revision of the European American values scale for Asian Americans using the Rasch model. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2005;37:194–207. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W-C, Chun C-A, Takeuchi DT, Myers HF, Siddarth P. Age of first onset major depression in Chinese Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;11:16–27. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK. The role of racial identity, ethnic identity, and Asian values as mediators of perceived discrimination and psychological well-being among Asian American college students (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim BS, Hong S. A psychometric revision of the Asian values scale using the Rasch model. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2004;37:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Hong S. First generation Korean American parents’ perceptions of discipline. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2007;23:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche M, Kim C, Hui MK, Joy A. An empirical study of multidimensional ethnic change. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1996;27:114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Lee BK. When East meets West: Acculturation and social-emotional adjustment in Canadian-Chinese adolescents (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) University of Western Ontario, Canada: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Sobal J, Frongillo EA. Comparison of models of acculturation: The case of Korean Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2003;34:282–296. [Google Scholar]

- Leong FTL, Okazaki S, Tak J. Assessment of depression and anxiety in east Asia. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15:290–305. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem R, Lim BA, Liem JH. Acculturation and emotion among Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2000;6:13–31. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorr M. Cluster analysis for social scientists. 1st ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mariño R, Stuart GW, Minas IH. Acculturation of values and behavior: A study of Vietnamese immigrants. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development. 2000;33:21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan GW, Cooper MC. An examination of procedures for determining the number of clusters in a data set. Psychometrika. 1985;50:159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Myles J, Hou F. Neighbourhood attainment and residential segregation among Toronto's visible minorities. Statistics Canada: Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, 206. 2003 Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=486146.

- Nguyen H, Messe LA, Stollak GE. Toward a more complex understanding of acculturation and adjustment: Cultural involvements and psychosocial functioning in Vietnamese youth. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1999;30:5–31. [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Kashiwagi K, Crystal D. Concepts of adaptive and maladaptive child behavior: A comparison of US and Japanese mothers of preschool-age children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2001;32:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Park YS, Kim BSK. Asian and European American cultural values and communication styles among Asian American and European American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:47–56. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena ED. Lost in translation: Methodological considerations in cross-cultural research. Child Development. 2007;78:1255–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity and self-esteem: A review and integration. In: Padilla AM, editor. Hispanic psychology: Critical issues in theory and research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Horenczyk G, Liebkind K, Vedder P. Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:493–510. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Immigrant America: A portrait. 2nd ed. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Roysircar-Sodowsky G, Maestas MV. Acculturation, ethnic identity, and acculturative stress: Evidence and measurement. In: Dana RH, editor. Handbook of cross-cultural and multicultural personality assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. pp. 131–172. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Alden LE, Paulhus DL. Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:49–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, Oppedal B. Acculturation as a developmental pathway. In: Lonner WJ, Dinnel DL, Hayes SA, Sattler DN, editors. Online readings in psychology and culture, unit 8. Western Washington University, Department of Psychology, Center for Cross-Cultural Research; Washington, DC: 2003. Retrieved from http://scholar works.gvsu.edu/orpc/vol8/iss1/6. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J. Acculturation in context: The self-esteem of Chinese immigrants. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2002;65:56–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL. Testing Berry's model of acculturation: A confirmatory latent class approach. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:275–285. doi: 10.1037/a0012818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle W, Ward C. The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1990;14:449–464. [Google Scholar]

- Shek DTL. What does the Chinese version of the Beck Depression Inventory measure in Chinese students—general psychopathology or depression? Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1991;47:381–390. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199105)47:3<381::aid-jclp2270470309>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen EK, Alden LE, Sochting I, Tsang P. Clinical observations of a Cantonese cognitive-behavioral treatment program for Chinese immigrants. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43:518–530. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surgeon General, US Public Health Services Office of the Surgeon General . Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. Individualism–collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:907–924. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.696169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh N-H, Rho YC, Lu FG, Sanders KM. Handbook of Mental Health and Acculturation in Asian American Families (Current Clinical Psychiatry) Humana Press; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Lin E-Y. There are homes at four corners of the sea: Acculturation and adaptation in overseas Chinese. In: Bond MH, editor. The Oxford handbook of Chinese psychology. Oxford University Press; Hong Kong, China: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Rana-Deuba A. Acculturation and adaptation revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1999;30(4):422–442. [Google Scholar]

- Ward JH. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1963;58:236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Ying Y. Immigration satisfaction of Chinese Americans: An empirical examination. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:3–16. [Google Scholar]