Abstract

HuR (ELAV1), an RNA binding protein abundant in cancer cells, primarily resides in the nucleus, but under specific stress (e.g., gemcitabine), HuR translocates to the cytoplasm where it tightly modulates the expression of mRNA survival cargo. Herein, we demonstrate for the first time that stressing pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) cells by treatment with DNA damaging anti-cancer agents (mitomycin C, oxaliplatin, cisplatin, carboplatin and a PARP-inhibitor) results in HuR’s translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Importantly, silencing HuR in PDA cells sensitized the cells to these agents, while overexpressing HuR caused resistance. HuR’s role in the efficacy of DNA damaging agents in PDA cells was, in part, attributed to the acute upregulation of WEE1 by HuR. WEE1, a mitotic inhibitor kinase, regulates the DNA damage repair pathway, and therapeutic inhibition of WEE1 in combination with chemotherapy is currently in early phase trials for the treatment of cancer. We validate WEE1 as a HuR target in vitro and in vivo by demonstrating: (1) direct binding of HuR to WEE1’s mRNA (a discrete 56-bp region residing in the 3’UTR), and (2) HuR siRNA silencing and overexpression directly affects the protein levels of WEE1, especially after DNA damage. HuR’s positive regulation of WEE1 increases γH2AX levels, induces Cdk1-phosphorylation and promotes cell cycle arrest at the G2/M transition. We describe a novel mechanism that PDA cells utilize to protect against DNA damage in which HuR post-transcriptionally regulates the expression and downstream function of WEE1 upon exposure to DNA damaging agents.

Keywords: DNA damage, γH2AX, WEE1, HuR, Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Introduction

Despite high-throughput sequencing of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) genomes (1), effective targeted therapies remain elusive. A recent phase III trial reported (2) that a combination of three DNA damaging agents (5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan; FOLFIRINOX) resulted in an improvement in response from 9.4% to 31.6% (p<0.001). Despite this significant progress, virtually all PDA patients acquire resistance to DNA damaging-based chemotherapies. Since all of the cytotoxic agents used to treat PDA, including the components of FOLFIRINOX, work through DNA damage, there is an urgent need to better understand how PDA cells respond to cytotoxic stress and develop either acute or acquired drug resistance.

Prior work reveals that cell cycle checkpoints enable cells to undergo DNA repair in response to DNA damage (3, 4); and defects in the DNA damage response (DDR) can lead to cancer (3). The DDR network encompasses several signaling pathways (3, 5) that ultimately recruit a cascade of proteins to the site of DNA damage. In normal cells, damaged DNA is typically repaired during the G1/S checkpoint (6, 7). In contrast, most cancer cells, including PDA cells, have defects in the G1/S checkpoint mainly due to genetic inactivation of TP53; therefore, in many instances cancer cells depend on the G2/M checkpoint to repair damaged DNA (6–8). The G2/M checkpoint depends predominantly on post-translational modification of cyclin-dependent kinase-1 (CDK1, also known as CDC2) by WEE1, a tyrosine kinase; and CDC25, a tyrosine phosphatase. WEE1 and Myt1 phosphorylate CDK1 at tyrosine-15 (Y15) and threonine-14 (T14), causing G2/M arrest during DNA replication (9–13). These molecular events provide a checkpoint for DNA repair to occur before cells progress into mitosis (14, 15).

Previously, WEE1’s activity has been shown to be down-regulated via proteasome-dependent degradation through phosphorylation by polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) (13). WEE1 activity is also reduced through ubiquitin-mediated degradation by ubiquitin ligase SCF, β-TrCP, and Tome-1 (16–18). Additionally, WEE1’s activation domain is responsible for its degradation through phosphorylation on Ser-472 (19). More recently, it was shown that Cdc14A takes part in WEE1 degradation through CDK-mediated phosphorylation of WEE1 on Ser-123 and Ser-139 (20). These multiple independent post-translational modifications function to inhibit WEE1’s kinase activity during the entry into mitosis.

The importance of WEE1 as a regulator of the G2/M checkpoint in cancer cells has been demonstrated. WEE1 has been found to be highly expressed in various cancer types and is thought to play a role in transformation (15, 21) as well as resistance to DNA damaging agents (22–24). In fact, inhibition of WEE1 by small interfering RNA (siRNA) silencing or a small molecule inhibitor (MK1775) in pre-clinical models abrogate the G2/M cell cycle arrest and drive cells into mitosis without successful DNA repair, resulting in reduced tumor growth (25–27). These findings are the basis for combining WEE1 inhibitors with chemotherapeutic agents as a potential therapeutic strategy (23, 24, 28). However, many questions remain unanswered such as: 1) whether WEE1 expression levels remain stable in response to DNA damage? And 2) what is the underlying mechanism that may govern WEE1 expression levels upon or during DNA damage?

A candidate mechanism of WEE1 regulation in response to DNA damage is post-transcriptional gene regulation. A key RNA binding protein in cancer, HuR, a member of the embryonic lethal abnormal vision 1 (ELAV1) family, is primarily localized to the nucleus (29). HuR binds to its target mRNAs that contain AU- or U- rich (ARE) elements in their 3’ UTR (30), and translocates to the cytoplasm upon specific stress and post-transcriptionally regulates specific mRNAs. Through this action, HuR affects several signaling pathways including cell cycle dynamics and cancer cell metabolism (31–33). In fact, we demonstrated that HuR affects response to different anti-cancer therapeutics such as a Death Receptor 5 agonist and gemcitabine through the regulation of specific mRNA targets (31, 32). Thus, we expanded our survey of anti-cancer agents and hypothesized that similarly HuR could regulate the efficiency DNA damage anti-cancer agents. Insights gained from this work have direct implications for optimizing front-line treatment (i.e., FOLFIRINOX) of PDA patients.

Material and Methods

Cell culture

MiaPaCa2, PL5, and Panc1 cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% FBS (Gibco/Invitrogen), 1% L-glutamine (Gibco/Invitrogen), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C in 5% humidified CO2 incubators. Transient transfections were performed as previously described (31, 32). Unless otherwise specified, all cells were treated with the IC50 values of the DNA damaging agents (mitomycin C (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), oxaliplatin (Sigma), cisplatin (USB, Ocala, FL), carboplatin (USB), gemcitabine (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN), and PARP inhibitor (ABT-888; Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) by adding directly into the culture medium.

Cytoplasmic, Nuclear and Whole cell Extracts

Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were isolated using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (ThermoScientific, Rockford, IL) as previously described (31). Whole cell lysates were prepared using RIPA lysis buffer (Invitrogen) supplemented with phosphatase inhibitor (Pierce; ThermoScientific) as previously described (31).

Western Blotting

Samples were mixed 1:1 with 2× Laemmli buffer and boiled for 5 min. Approximately 10–50 µg of protein were separated as previously described (32). The membrane was blocked in 3% Bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated with HuR (3A2, 1:1,000, Santa Cruz, CA), GAPDH (1:1,000, Cell Signaling), γH2AX (1:1,000, Millipore), pCDK1-Y15 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling), CDK1 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling), Lamin A/C (1:1,000, Cell Signaling), hnRNP (1:1,000, Santa Cruz) or WEE1 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling) antibodies. Protein complexes were visualized with ECL (ThermoScientific) or Licor.

Immunofluorescence

HuR subcellular localization

MiaPaCa2 cells plated onto chamber slides at 1,000 cells per chamber cell density. After treatments, cells were processed as previously described (31) and analyzed with a Zeiss LSM-510 Confocal Laser Microscope.

γH2AX foci detection

Cells were seeded at 104 cell density on coverslips in 6-well plates. Cells were treated with MMC, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min in the dark at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton-X for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were incubated with γH2AX antibody (Millipore) for 1 h at 37°C followed by Alexa Fluor 488 F anti-mouse secondary antibody for 1 h in the dark at room temperature. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (Invitrogen) and mounted for analysis with a Zeiss LSM-510 Confocal Laser Microscope. Approximately 100–150 cells were used for counting the number of foci using ImageJ 1.47a software (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded at 106 cell density in T-75 flasks and treated with MMC (150 nM) for 2 h, washed 3 times with PBS, replenished with fresh complete media and incubated for 24 h. BrdU (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) was added to actively growing cells for 1 h and cells were fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol for 2 h. Cells were denatured with 2 M HCl for 20 min and neutralized with 0.1 M sodium borate, and probed with FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Cells were, washed and re-suspended in 10 µg/ml propidium iodide supplemented with 100 µg/ml RNase for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Samples were analyzed on flow cytometry BD FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Time-lapse video microscopy

MiaPaCa2 cells stably expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP):histone H2B were seeded in 6 cm dishes and 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with MMC (150 nM) for 2 h. MMC was removed by washing cells 3 times with PBS, followed by replenishment with complete media. Cells were then supplemented with HEPES (25 mM), layered with mineral oil (Sigma) and placed into a housing chamber which maintained the temperature at 37°C. Using a Nikon TE2000 microscope (Nikon) controlled by MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices), bright field and fluorescent images were captured every 5 min for up to 48 h. Individual movies were manually analyzed using MetaMorph software (Molecular devices) and approximately 100 cells per sample were assessed for the indicated measurements. Visible chromosome condensation was used score mitotic cells, with telophase chromosomes marking the end of mitosis. Chromosome fragmentation was used to score apoptotic cells. Selected frames representing different cell morphologies are presented as montages.

Cell Growth, Drug Sensitivity and Apoptosis Assays

Soft-agar anchorage independence growth assay

Cell growth assays were performed in 60 mm tissue culture dishes (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). A bottom layer of 0.75% agar was prepared in the complete media. A top layer was prepared with 0.36% agar supplemented with 104 cells/ml. Dishes were incubated at 37°C for 3 weeks and colonies were counted.

Drug Sensitivity Assay

Transfected cells were seeded at 1,000 cells per well in 96-well plates in triplicate, and treated after 24 h and stained as previously described (31). Scatter plots were generated using Excel (Microsoft, Santa Rosa, CA).

Apoptosis Assays

Transfected cells were treated with MMC (150 nM) for 16 h. Annexin V13242 labeling kit (Invitrogen) was used following manufacture’s protocol to measure apoptosis using flow cytometry on a BD Biosciences FACS Calibur system (BD Biosciences).

Ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation (RNP-IP) assays

MiaPaCa2 cells were plated at 30 – 50% confluency in T-150 flasks and treated with gemcitabine (1 µM) for 12 h or MMC (150 nM) for 16 h. Immunoprecipitation was performed using either anti-HuR or IgG control antibodies as described previously (31). RNA was isolated from the immunoprecipitation, and WEE1 mRNA binding was validated via RT-qPCR.

In-vivo RNP-IP assay

Mouse studies were conducted at Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-accredited Thomas Jefferson University, and all study protocols were approved by IACUC (Protocol Number 832B). MiaPaCa2 cells were injected at 5 million cells s.c. (n = 16) and allowed to grow for 4 weeks. Mice were treated once intra-peritoneally (i.p.) with gemcitabine (1 mg/kg) for 12 h and euthanized. Tumors were harvested and lysed using digitonin based buffer (see above). Immunoprecipitation was performed using either anti-HuR or IgG control antibodies as described previously (31).

Luciferase assay

PCR products corresponding to the 56-bp of WEE1 3’UTR and mutations in the 56-bp of WEE1 3’UTR region were purified and cloned into Promega psiCHECK2 luciferase vector (Promega). MiaPaCa2 cells were transfected with these plasmids in 6-well plates. After 48 h of transfections, cells were treated and luciferase activity was measured with a luciferase assay report kit (Promega) as previously described (32). For double transfections, cells were first transfected with siRNA HuR or control and 24 h later transfected with luciferase constructs.

Results

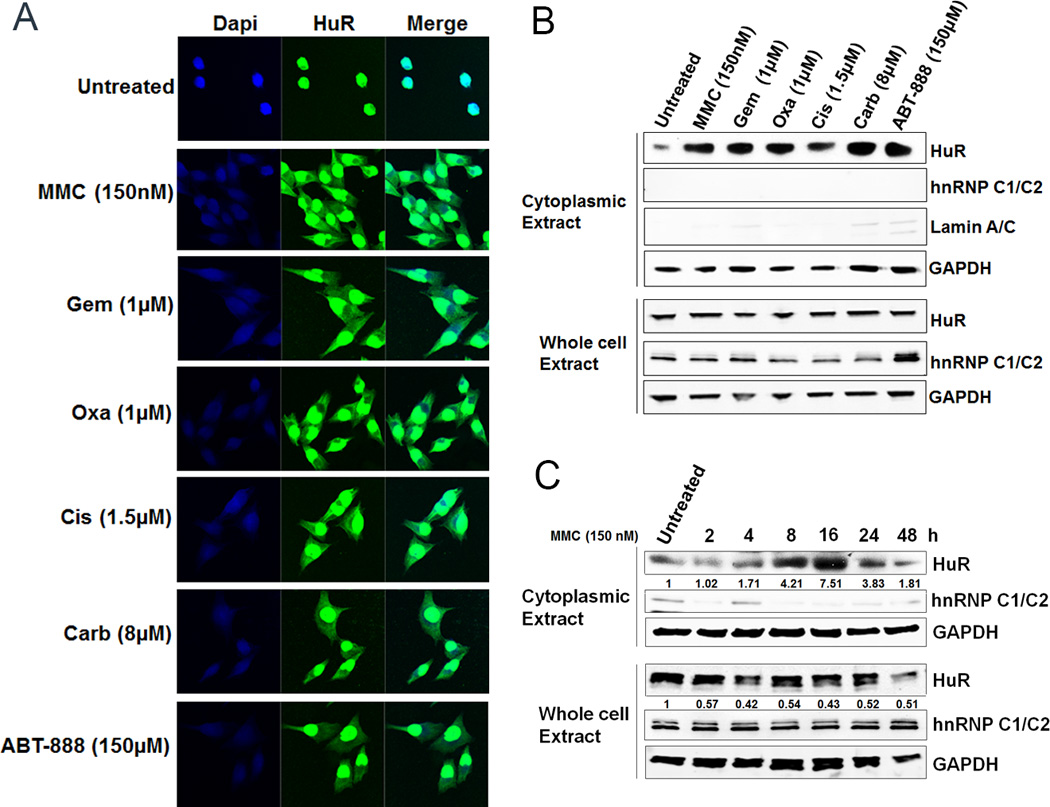

DNA damaging agents induce HuR translocation

MiaPaCa2 cells were stressed with pre-determined IC50 doses (Supplementary Table S1) of chemotherapies for 12 hours: mitomycin C (MMC), oxaliplatin (Oxa), cisplatin (Cis) and carboplatin (Carb), PARP inhibitor (ABT-888), and the positive control gemcitabine (GEM) (31). First, an immunofluorescence (IF) assay validated that HuR was primarily localized to the nucleus in untreated cells while HuR was predominantly cytoplasmic after treatment (Fig. 1A). Immunoblotting demonstrated a high abundance of cytoplasmic HuR in all treated lysates (Fig. 1B and Supplementary S1D), while HuR expression in whole cell and nuclear lysates did not significantly change (Fig. 1B and Supplementary S1A). Specifically, cytoplasmic HuR levels increased after 4 hours in MiaPaCa2 cells treated with MMC compared to untreated cells. Peak enhanced cytoplasmic HuR levels occurred 16 hours post-treatment and decreased back to baseline levels 48 hours after treatment (Fig. 1C and Supplementary S1E). Panc1 and PL5 cells demonstrated enhanced cytoplasmic HuR levels at 24 hours after MMC treatment and then a decline in cytoplasmic HuR levels after 36 hours (Supplementary Fig. S1F). Similarly, enhanced cytoplasmic HuR accumulation was detected in MiaPaCa2 cells after 2 hours of oxaliplatin treatment (1 µM), peaking after 8 hours and decreasing back to baseline after 36 hours (Supplementary Fig. S1C). For MiaPaCa2, PL5 and Panc1 cells, HuR protein expression in whole cell and nuclear lysates did not significantly change between cells treated with MMC or oxaliplatin as compared to the untreated controls (Supplementary Fig. S1B–C and S1F), indicating that these compounds enhance HuR translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm.

Figure 1.

Chemotherapeutic agents induce HuR translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. A, MiaPaCa2 cells after treatment with DNA damaging agents showed HuR cytoplasmic localization. B, Cytoplasmic HuR abundance increases after treatment with IC50 doses of chemotherapies while total HuR was not significantly altered. C, MiaPaCa2 cells treated with MMC (150 nM) showed time-dependent increase in HuR cytoplasmic levels. The numbers indicate relative HuR expression normalized to GAPDH.

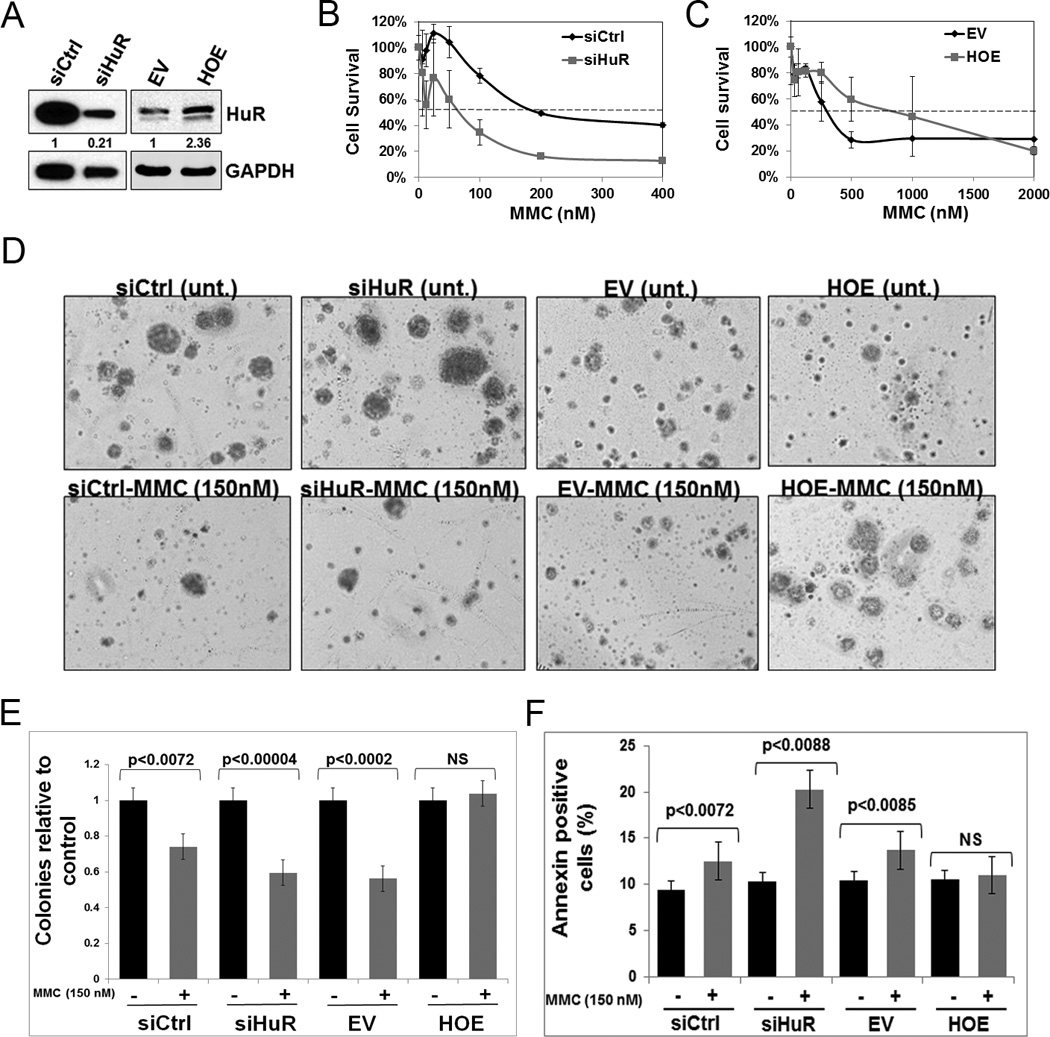

HuR manipulation alters chemotherapeutic efficacy

Short-term cell survival assay

Having established that DNA damaging agents induce HuR translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, we determined the impact of this activity on PDA cell sensitivity to these agents. A cell survival assay was performed in MiaPaCa2 and Panc1 cells transiently transfected with: a) siRNA oligos against HuR (siHuR) and control (siCtrl) sequences; or b) with a plasmid overexpressing HuR (HOE) and control empty vector (EV) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S2C). In the majority of DNA damaging agents tested (MMC, Oxa, Cis, Carb and ABT-888), HuR-silenced MiaPaCa2 and Panc1 cells showed reduced cell survival compared to control cells (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. S2A, S2D and S2F). Accordingly, HuR-overexpressing cells showed increased resistance against these DNA damaging agents (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Fig. S2B, S2E and S2G).

Figure 2.

HuR manipulation alters chemotherapeutic efficacy. A, HuR expression in MiaPaCa2 cells after transfections with siCtrl, siHuR, EV or HOE. The numbers indicate relative HuR expression normalized to GAPDH. B and C, Cell survival assay after treatment with MMC, assessed after 7 days. D and E, Soft agar colony formation assay after treatment with MMC (150 nM), assessed after 21 days. F, The percentage of Annexin V staining after MMC (150 nM) treatment. Error bars indicate the standard deviation between three replicates in B, C, E and F. NS: Not significant.

Long-term cell survival assay

We focused on understanding the efficacy of MMC, a potent DNA crosslinker that causes severe DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) (34). To further characterize the impact of HuR on MMC efficacy, we observed colony formation for 3 weeks in MiaPaCa2 cells. The number of colonies formed in control and HuR-silenced cells upon MMC treatment were not dramatically different (Fig. 2D–E). In contrast, when HuR was overexpressed, MMC failed to reduce the number of colonies indicating that cells became resistant to MMC treatment (Fig. 2D–E). Additionally, we observed differences in the microscopic appearance of colonies after MMC treatment depending on whether HuR was silenced or overexpressed. Specifically, colony size of cells treated with MMC in HuR-silenced and control conditions was reduced while HuR overexpressing cells maintained colony size as compared to the controls (Fig. 2D).

Apoptosis analysis

Apoptosis significantly increased with MMC treatment in HuR-silenced cells, from 10% to 20%. In contrast, no dramatic increase was observed in the siRNA control cells. Consistent with cell survival assays above, HuR overexpression appeared to protect cells from apoptosis with MMC treatment (Fig. 2F). These results indicate that HuR expression plays a critical role in modulating PDA cell response to MMC treatment.

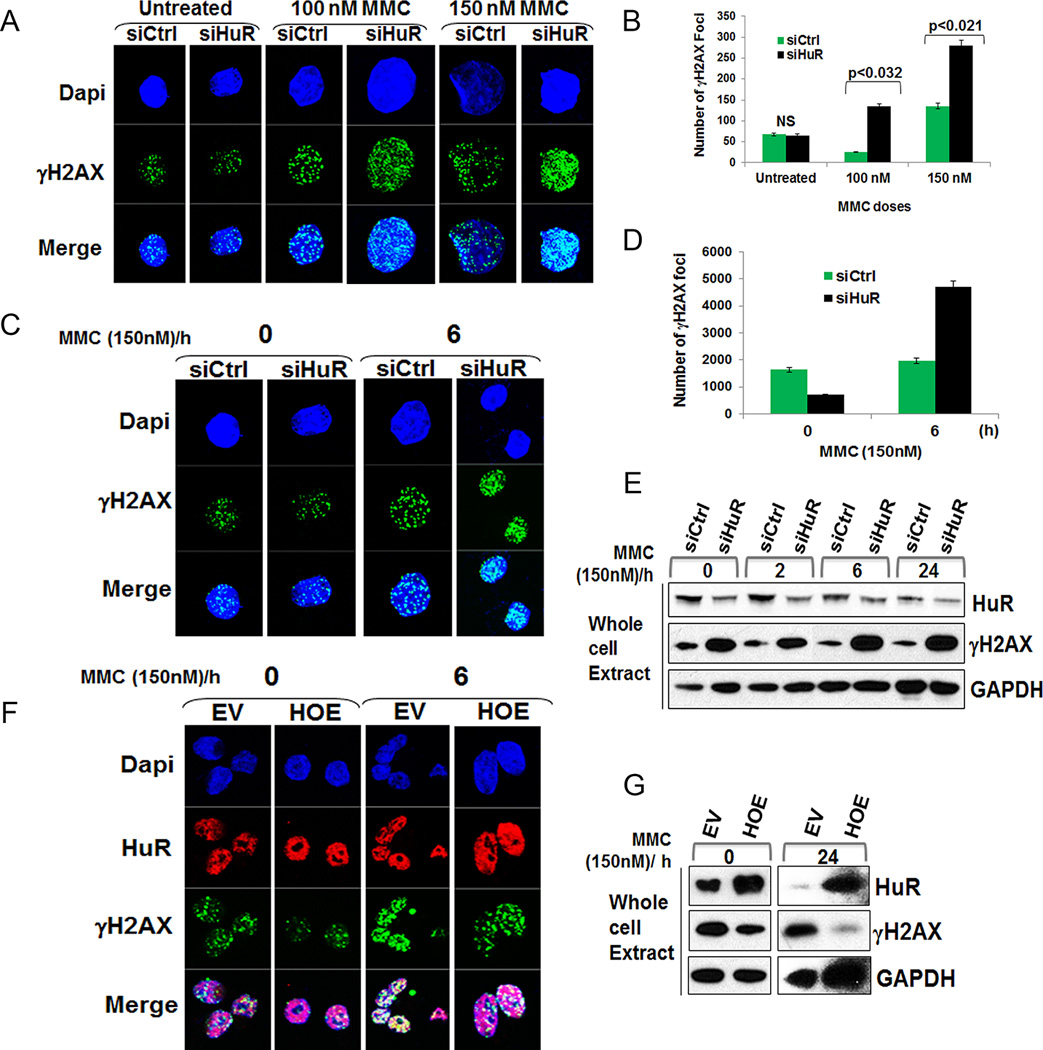

HuR silencing enhances DNA damage breaks in PDA cells

Since HuR levels directly affected chemotherapeutic efficacy, we next investigated HuR’s role in the DDR upon MMC exposure. Control and HuR-silenced cells were treated with variable doses of MMC for 6 hours. This time point was selected based on the determined time-course of HuR translocation and its predicted time of affecting the downstream events related to the DDR (Fig. 1C). Histone H2AX phosphorylation at serine-139 (also known as γH2AX), is an established marker of DSBs (35). Under no treatment, IF assay detected some baseline background γH2AX foci formation in both control and HuR-silenced cells (Fig. 3A–B). MMC treatment increased γH2AX foci in both control and HuR-silenced cells, indicating that MMC treatment induced DNA damage (Fig. 3A–B). However, HuR-silenced cells treated with MMC (150 nM) had dramatically increased γH2AX foci formation compared to control cells demonstrating that DNA damage persisted and DNA repair was considerably delayed in the absence of HuR (Fig. 3A–B).

Figure 3.

HuR silencing enhanced DNA damage breaks. A, Cells treated with MMC for 6 h showing γH2AX foci formation. B, Approximately 100–150 nuclei were evaluated for γH2AX foci formation for each sample. NS: Not significant. C, Transfected cells treated with MMC (150 nM) for 2 h, washed with PBS, replenished with complete media and fixed at indicated time points showing increased γH2AX foci formation after 6 h in siHuR cells. D, A total of 120 nuclei was evaluated for γH2AX foci formation for each sample. The numbers indicate the total number of foci for each sample. E, siHuR transfected cells showed increase in γH2AX levels after 6 h. F, Transfected cells were treated with MMC (150 nM) for 2 h, washed with PBS, replenished with complete media and fixed at indicated time points showing reduced γH2AX foci formation after 6 h in HOE cells. G, Representative immunoblot of H2AX phosphorylation decreases after HuR overexpression following MMC treatment.

Manipulation of HuR levels modulates the DDR

We next assessed whether HuR plays a role in DNA repair. MiaPaCa2 and PL5 cells (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. S3A) transfected with control or HuR siRNA were treated with MMC (150 nM) for 2 hours. This dose was chosen based on a pre-determined IC50 value enough to induce DNA damage without causing significant cell death (Fig. 2B). After 2 hours of MMC treatment, cells were washed to remove MMC and replenished with fresh complete media and allowed to repair DNA. The IF assay revealed that MMC treatment induced γH2AX foci in both control and HuR-silenced cells after 2 hours of MMC treatment and 0 hour of repair, indicating the presence of DNA damage breaks (Fig. 3C–D and Supplementary Fig. S3B). Remarkably, 6 hours after washing MMC the number of γH2AX foci increased significantly in HuR-silenced cells compared to the control (Fig. 3C–D and Supplementary Fig. S3B). These findings suggest that DNA damage persisted and DNA repair was considerably delayed in the absence of HuR. Immunoblot analysis of protein lysates validated this finding, demonstrating that HuR status affects H2AX phosphorylation following MMC treatment (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. S3C). Accordingly, HuR overexpression reduced γH2AX foci formation and phosphorylation following MMC treatment (Fig. 3F–G and Supplementary Fig. S3C). These data suggest that HuR silencing enhances MMC efficacy in PDA cells. Since total H2AX levels were affected upon MMC treatment (data not shown), we evaluated the possibility that HuR silencing combined with MMC treatment might directly affect protein expression. We performed RT-qPCR on HuR-bound mRNA (from RNP-IP) and did not observe any significant binding of HuR to H2AX mRNA (Supplementary Fig. S3D).

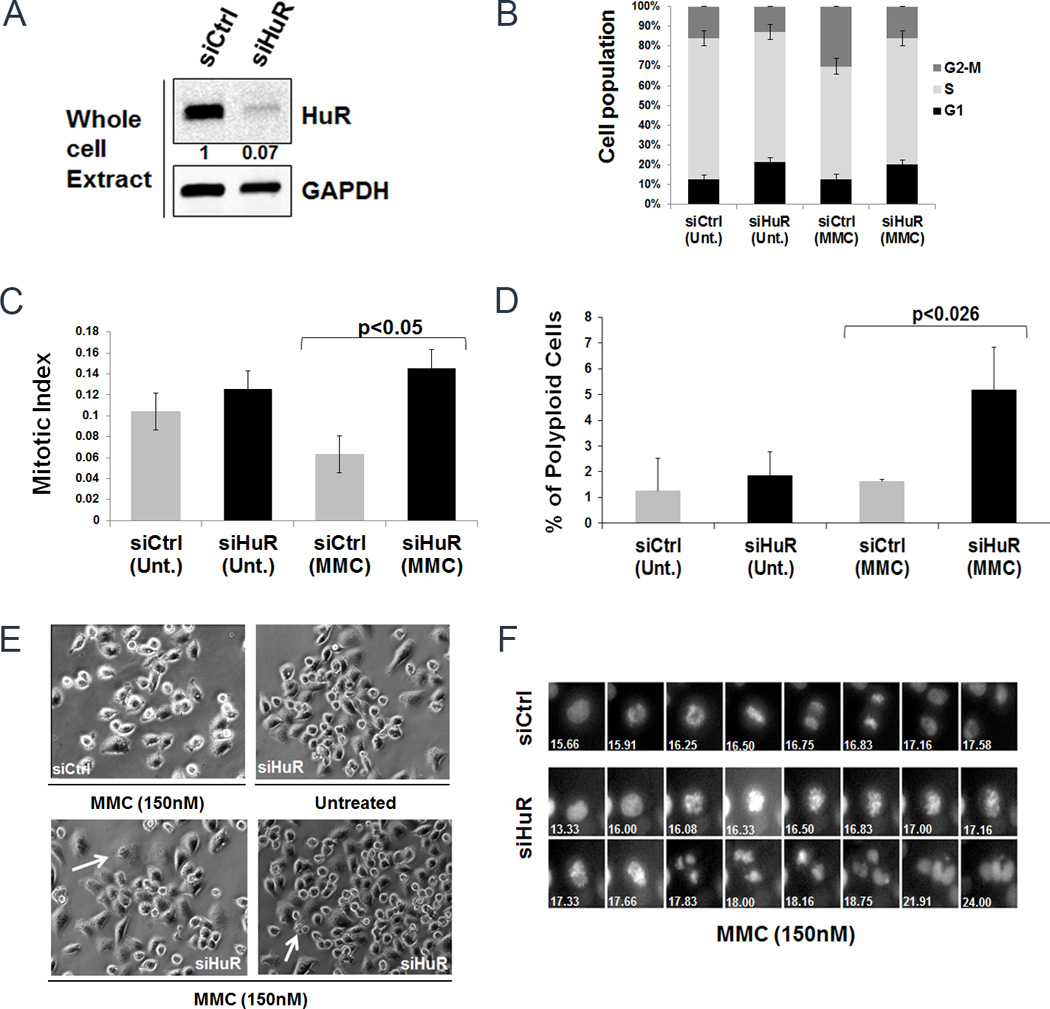

HuR silencing affects the cell cycle progression following DNA damage

We determined the effect of HuR silencing on cell cycle kinetics in PDA cells in the context of DNA damage. After 48 hours of transfection, control and HuR-silenced cells (Fig. 4A) were exposed to MMC (150 nM) for 2 hours. We found that cell cycle progression was not adversely impaired by HuR silencing compared to control cells. Although, we observed a slightly higher percentage of cells in G2/M phase in HuR-silenced cells after 2 hours of MMC treatment compared to control-treated cells (data not shown), we detected a higher percentage of cells in G2/M phase, after 24 hours, in control treated cells as compared to untreated control or HuR-silenced cells (Fig. 4B), consistent with previous reports of a MMC induced G2/M arrest in PDA cells at a longer time points (36). To further corroborate the effects of HuR silencing and MMC treatment on cell cycle dynamics, we performed live cell video-microscopy using MiaPaCa2 cells stably expressing GFP:Histone H2B. Control siRNA cells that were treated with MMC reduced the number of cells to enter mitosis. However, in HuR-silenced cells, the effect of MMC in causing reduced cell cycle progression was augmented (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Movies S1–3). Quantification of time-lapse movies showed that control siRNA treated cells entered mitosis approximately 15 hours after treatment, while HuR siRNA treated cells entered into mitosis 2 hours earlier than control cells. However, HuR siRNA and MMC-treated cells either died in mitosis or exited later than control cells (Fig. 4F – siRNA control greater than 17 hours and siRNA HuR greater than 24 hours). Moreover, the fidelity of the mitoses in HuR-silenced cells was greatly impaired, resulting in the increase (~3-fold) of polyploid cells (Fig. 4D–E and Supplementary Movies S1–3), suggesting that they undergo mitotic catastrophe in the absence of HuR expression. These results are consistent with the notion that HuR silencing increases the cytotoxic effect of MMC in PDA cells and forces cells to enter mitosis without adequate DNA repair.

Figure 4.

HuR manipulation upon DNA damage enhances accumulation of cells in mitotic phase. A, HuR expression levels were analyzed by immunoblot of lysates from MiaPaCa2 cells transfected with siCtrl or siHuR. The numbers indicate relative HuR expression normalized to GAPDH. B, Cell cycle kinetics after treatment with MMC (150 nM). Error bars indicate the standard deviation between three replicates with p<0.05. C, MiaPaCa2 cells stably expressing GFP:H2B were used for live cell video-microscopy. After transfection cells were treated with MMC (150 nM) and subjected to live cell imaging. The graph represents the number of cells progressing through mitosis. D, The graph represents the percentage of polyploidy cells in mitosis. Error bars indicate the standard deviation between three replicates in both C and D. E, A still image of the cells showing multinucleated phenotype (arrow). F, Representative montage of cells progressing through mitosis. Numbers indicate time in hours.

WEE1, a mitotic inhibitor, is a novel HuR target

In order to find novel HuR targets in the cell cycle and DDR pathways, we performed RNP-IP assay (31) in MiaPaCa2 cells using an antibody against HuR. HuR-bound mRNA transcripts were isolated and identified by sequencing analysis (Unpublished data; EL, IR and JB). Concurrently, we performed a genome-wide siRNA screen under low-dose gemcitabine therapy to identify genes whose silencing sensitized MiaPaCa2 cells to DNA damage (Unpublished data; VB, TY, JB). Data from these two screening strategies were integrated and WEE1 was identified as a novel HuR target in the DDR pathway.

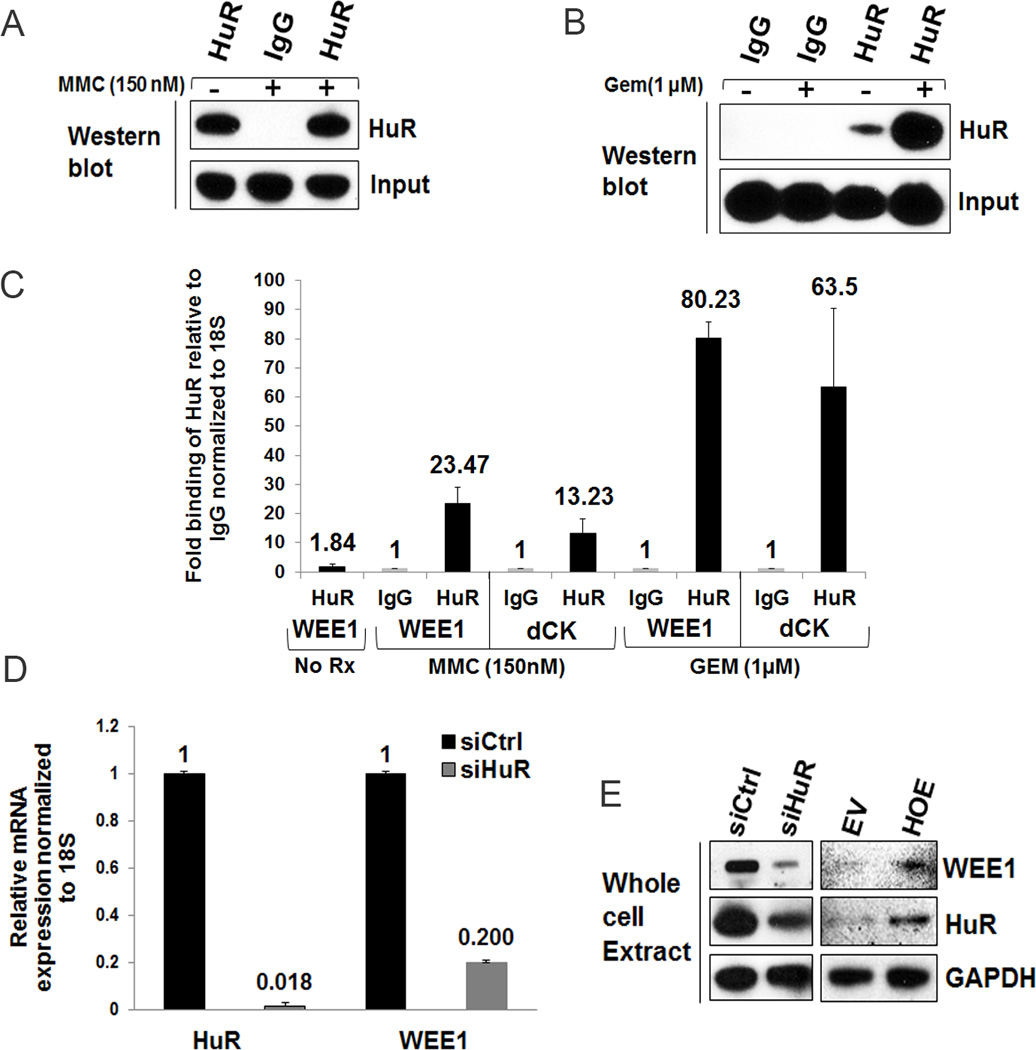

Validation that WEE1 is a bona fide HuR target upon chemotherapeutic stress

We next performed an RNP-IP assay in the presence or absence of chemotherapeutic stress to validate the association of the HuR protein with endogenous WEE1 mRNA. MiaPaCa2 cells were stressed with gemcitabine (1 µM) for 12 hours and MMC (150 nM) for 16 hours. An RNP-IP with a HuR antibody was performed to test the binding of HuR with WEE1 (IgG RNP-IP was performed as a negative control) (Fig. 5A–C). The WEE1 expression was enriched by 80-fold upon gemcitabine treatment and 23-fold upon MMC treatment in the HuR-IP, compared to an IgG control-IP (Fig. 5C). As a positive control, dCK mRNA (a known HuR target (31)) was enriched by 13-fold upon MMC stress and 63-fold upon gemcitabine stress, (Fig. 5C). In addition, we confirmed the binding of HuR with WEE1 under another established HuR stressor, tamoxifen (37) (Supplementary Fig. S4A–B). These results indicate that WEE1 is a bona fide HuR target. We further verified WEE1 expression levels upon HuR manipulation. HuR silencing resulted in significant down-regulation of WEE1 at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 5D–E). Accordingly, overexpressing HuR increased WEE1 levels indicating that HuR regulates WEE1 expression (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

WEE1, a mitotic inhibitor, is a novel HuR target in DNA damage control pathway. A and B, immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitates isolated from MMC-treated (A) and GEM-treated (B) PDA cells using either control IgG or anti-HuR antibodies. C, RNP-IP analysis of MiaCaPa2 cells treated with GEM (1 µM) for 12 h and MMC (150 nM) for 16 h. HuR binding to WEE1 mRNA was analyzed by RT-qPCR. D, WEE1 and HuR mRNA levels were analyzed by RT-qPCR in transfected cells. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from three replicates in C and D. E, Immunoblot analysis of WEE1 and HuR protein levels.

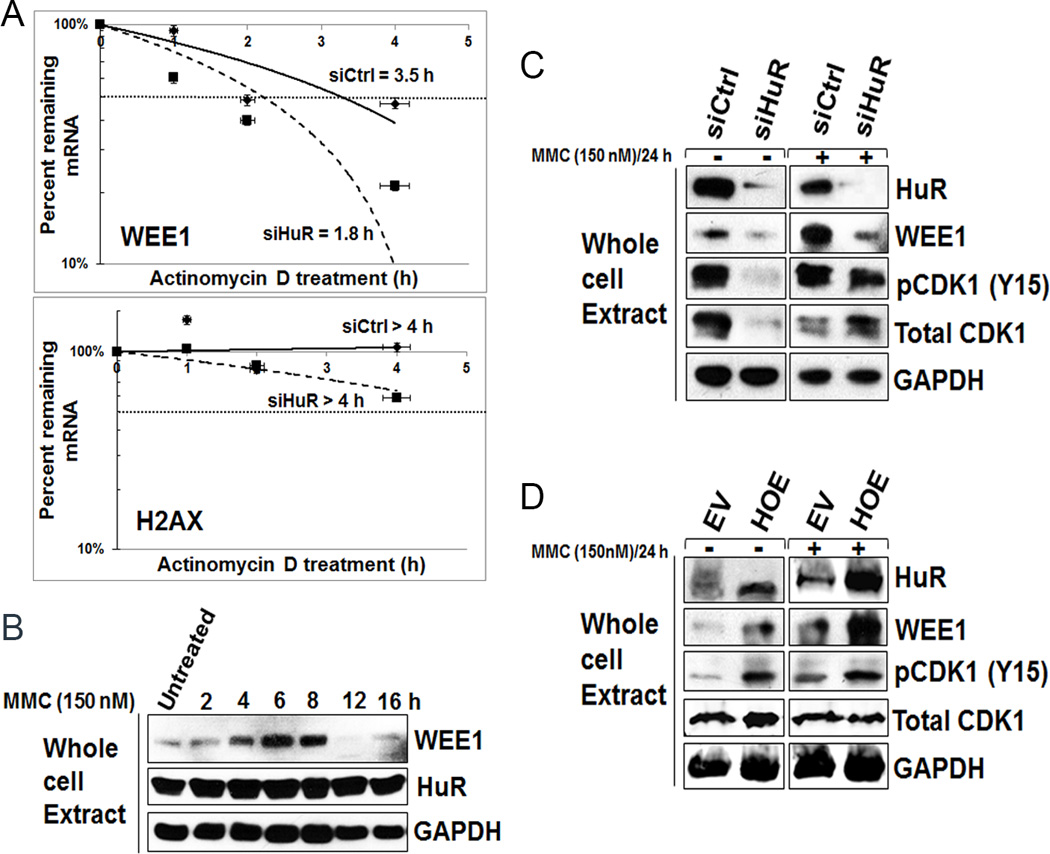

WEE1 is post-transcriptionally regulated by HuR upon DNA damage

HuR typically regulates target protein expression by either affecting RNA stability or facilitating protein translation (38). To investigate whether HuR regulates WEE1 through mRNA stability or protein translation upon DNA damage, we treated cells 48 hours after transfection with MMC (150 nM) for 2 hours and analyzed mRNA half-life after actinomycin D treatment, which inhibits transcription. As a control, mRNA stability of H2AX and GAPDH (both are not HuR targets) were also analyzed. In control treated cells, WEE1 mRNA levels degraded with a half-life of approximately 3.5 hours. In contrast, WEE1 mRNA in HuR-silenced MMC-treated cells degraded at a faster rate, with an estimated half-life of 1.8 hours (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Fig. S5A). These data demonstrate that HuR enhances WEE1 mRNA stability. WEE1 protein levels in MiaPaCa2 cells increased significantly after 4 hours of MMC treatment, corresponding with the time when HuR becomes cytoplasmic (Fig. 1C), and dramatically reduced after 12 hours (Fig. 6B). WEE1 expression levels upon MMC treatment in Panc1 cells also increased after 2 hours and reduced after 36 hours (Fig. S5B). Similarly, in PL5 cells, this pattern persisted with WEE1 levels increasing after 2 hours of treatment prior to returning below baseline after 36 hours (Supplementary Fig. S5C). Similar patterns of WEE1 protein expression were observed when MiaPaCa2 cells were treated with oxaliplatin (1 µM) and gemcitabine (1 µM) (Supplementary Fig. S5D–E). Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that HuR stabilizes WEE1 mRNA and post-transcriptionally regulates WEE1 upon DNA damage insult.

Figure 6.

WEE1 is post-transcriptionally regulated upon MMC treatment. A, WEE1 mRNA stability was analyzed after MMC (150 nM) followed by actinomycin D treatment in siCtrl and siHuR cells. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from three replicates. B, WEE1 protein levels increase in MiaPaCa2 cells after MMC (150 nM) treatment. C and D, WEE1 and pCDK1-Y15 signals abolished after HuR silencing (C) while restored after HuR overexpression (D).

Functional implications of HuR’s regulation of WEE1

WEE1 affects downstream cell cycle regulators (e.g. CDK1) resulting in cell cycle arrest (10, 12). In order to determine the impact of HuR inhibition on MMC-induced DNA damage and cell cycle regulation, we evaluated protein expression of WEE1 and phosphorylated CDK1 in MiaPaCa2 and Panc1 cells. Following transfection with siRNA HuR or control oligos, cells were exposed to MMC (150 nM) for 2 hours, washed, and replenished with complete media to allow for DNA repair over 24 hours. Consistent with prior experiments (Fig. 5E), HuR silencing reduced WEE1 expression in both MiaPaCa2 (Fig. 6C and Supplementary Fig. S5H) and Panc1 cells (Supplementary Fig. S5F). Further, HuR silencing also resulted in the reduced phosphorylation of CDK1, a key cell cycle regulator at G2/M phase (Fig. 6C and Supplementary Fig. S5F), particularly under untreated conditions. Accordingly, HuR overexpression also resulted in enhanced phosphorylation of CDK1 (Fig. 6D and Supplementary Fig. S5G and Fig. S5I) in both untreated and MMC treated samples, providing mechanistic evidence of the G2/M arrest upon MMC treatment (Fig. 6D and Supplementary Fig. S5G). Moreover, reduced phosphorylation of H2AX (i.e., decreased double strand breaks) was observed in HuR overexpressed lysates, further demonstrating HuR’s effects on the efficacy of MMC and the DDR (Fig. 3G). These data demonstrate that HuR can mediate the DNA damage response via post-transcriptionally regulating WEE1 which leads to the inhibitory phosphorylation of CDK1 and G2/M cell cycle arrest (Fig. 5–6 and Supplementary Fig. S4–S5).

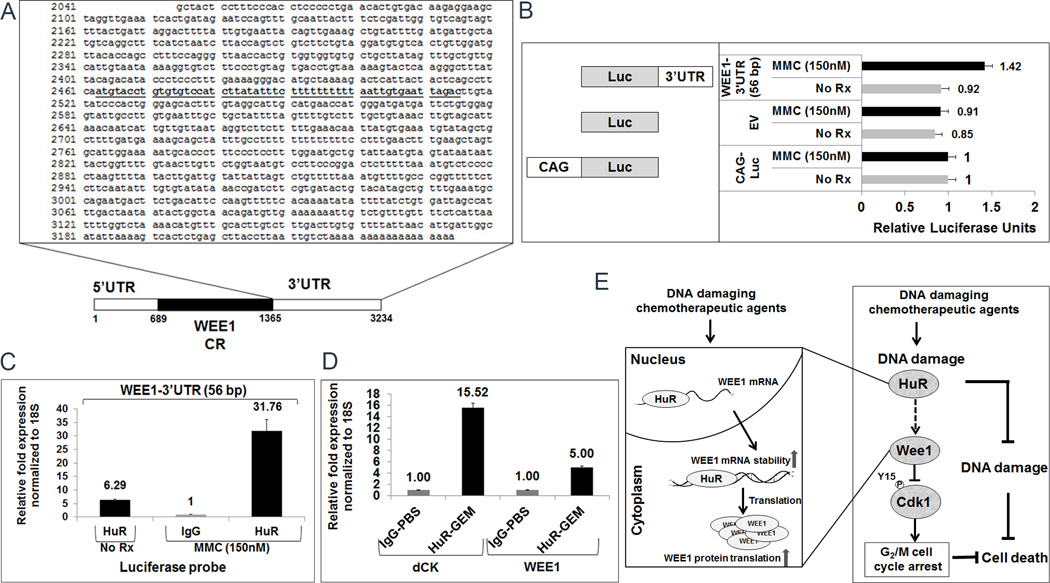

HuR binds to the WEE1 mRNA via 3’UTR

In order to determine the molecular interaction between HuR and WEE1 mRNA, we identified HuR binding sites in the 3’UTR of WEE1 by analyzing publicly available HuR-cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP) datasets (39–41). The WEE1 transcript contains a HuR binding site in its 3’UTR (Fig. 7A). To independently confirm the binding site in our context, the 56 bp putative HuR binding site sequence was subcloned into a luciferase expression construct and transfected into MiaPaCa2 cells (Fig. 7B; left panel) (31, 32). A construct with CAG promoter that ubiquitously drives luciferase was used as a positive control (Fig. 7B; left panel). After 48 hours of transfection, cells were treated with MMC (150 nM) for 2 hours and luciferase activity was measured. Results showed increased luciferase activity in 3’UTR (56 bp) construct compared to the empty vector, providing support that HuR regulates WEE1 expression through this binding site (Fig. 7B; right panel). Moreover, these data prove that target protein expression and function are induced by stressors (e.g., MMC) that activate HuR. In addition, cells transfected with the constructs were also treated with gemcitabine (1 µM) and oxaliplatin (1 µM) for 2 hours and results showed more than 2-fold increase in the luciferase activity suggesting that HuR’s regulation of WEE1 through 3’UTR is not entirely stress- dependent (Supplementary Fig. S6A).

Figure 7.

HuR binds to the WEE1 mRNA via 3’UTR. A, Schematic of the 3′ UTR sequence of WEE1. The putative HuR binding site is underlined. CR: coding region; UTR: untranslated region B, Schematic of the constructs used for transfection studies (left panel). WEE1-3’UTR (56 bp) sequences are cloned into pCHECK2 luciferase vector. A plasmid without WEE1-3’UTR (56 bp) sequence (Empty vector; EV) was used as a control. CAG- driven promoter construct was used to normalize the luciferase activity. All three plasmids were transfected into MiaPaCa2 cells treated with MMC (150 nM) for 2 h before luciferase activity was measured (right panel). Error bars indicate the standard deviation between three replicates. C, HuR binding to WEE1-3’UTR (56 bp) mRNA was analyzed by RT-qPCR using a luciferase probe. D, RNP-IP analysis of mouse xenograft treated with inter-peritoneal GEM (1 µM) for 12 h before the tumor tissues were harvested. HuR binding to WEE1 and dCK (positive control) mRNA was analyzed by RT-qPCR. E, Schematic of HuR’s role in the DDR pathway and a novel mechanism of drug resistance to common cytotoxic therapies. Chemotherapy results in the activation of HuR (i.e. HuR translocates to the cytoplasm from the nucleus) and subsequent stabilization of the WEE1 transcript, thereby causing cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase and enhancing DNA repair.

To validate that the 56 bp binding sequence directly binds to HuR, an RNP-IP assay with a HuR antibody and IgG as a negative control was performed. After 48 hours, MiaPaCa2 cells that were transfected with WEE1-3’UTR (56 bp) construct are treated with MMC (150 nM) for 16 hours. RT-qPCR analysis with a luciferase probe showed more than 31-fold increase upon MMC treatment confirming the specificity of HuR binding to 56 bp region in WEE1 3’UTR (Fig. 7C). We next co-transfected the MiaPaCa2 cells with WEE1-3’UTR (56 bp) construct and siHuR along with appropriate controls. After 48 hours of transfection, cells were treated with MMC (150 nM), gemcitabine (1 µM) and oxaliplatin (1 µM) for 2 hours. Results showed a significant decrease in luciferase activity when HuR was silenced, demonstrating the dependence on HuR for regulation of this construct (Supplementary Fig. S6B). We further validated the binding of HuR to the 56 bp site by creating two deletion constructs in the WEE1-3’UTR (56 bp) construct. The first deletional construct contains the first half while the second construct contains the c-terminal end of the 56 bp sequence. The luciferase activity was significantly decreased in the deletion constructs confirming the specificity and the importance of the entire 56 bp binding sequence of WEE1 regulation by HuR (Supplementary Fig. S6C).

WEE1 mRNA binds to HuR in vivo

We validated in-vivo HuR regulation of WEE1 in a mouse PDA xenograft model. MiaPaCa2 PDA cells were injected into a mouse (i.e., xenografted) and treated with intraperitoneal gemcitabine (1 mg/kg) for 12 h. Tumors were harvested and an RNP-IP assay with a HuR antibody and IgG as a negative control was performed. RT-qPCR validated that WEE1 expression increased up to 5-fold and dCK mRNA (a known HuR target) increased up to 15-fold upon gemcitabine treatment compared to an IgG control-IP (Fig. 7D). These results indicate that HuR regulates WEE1 under chemotherapeutic stress in vivo.

Discussion

In-depth understanding of WEE1’s regulation of cell cycle dynamics and related aspects of the DDR stems from work performed by Novel Prize winner Paul Nurse (42) and this basic work has recently been translated to pre-clinical models. Previously, it has been shown that WEE1 levels are balanced by its degradation and synthesis throughout the cell cycle (i.e., on the onset of mitosis, WEE1 levels are low, while during S and G2 phases, WEE1 levels increase) (12). WEE1’s degradation is achieved by several phospho-dependent mechanisms. In the current study, we provide the first evidence that this cell cycle checkpoint kinase is also tightly regulated by RNA binding protein HuR. Thus, we provide evidence that post-transcriptional regulation of WEE1 by HuR may be critical for PDA cell survival under clinically relevant drug exposure. These findings are particularly intriguing in light of recent discoveries that have shown that inhibition of WEE1 can sensitize various chemotherapeutic agents to cancer cells, and hence this strategy is being tested pre-clinically and in the clinic (21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 43). Specifically, this strategy is being tested with the WEE1 inhibitor, MK-1775, which has been shown to sensitize cancer cells to DNA damaging agents by disrupting the G2/M arrest (44). In this study, we put forth a novel acute checkpoint mechanism (which involves WEE1) by which cells can arrest and potentially ‘out last’ any abrupt DNA damage insult encountered (e.g., chemotherapy exposure). This checkpoint mechanism, like most in the cell cycle, is highly regulated. For example, building on previous work (45), HuR’s regulation of WEE1 can, in turn, inhibit CDK1’s ability to keep HuR ‘inactive’ in the nucleus (Fig. 7E).

These findings open up new questions. First, we have not addressed whether this mechanism is unique to cancer cells, although it is of note that HuR levels are more abundant in cancer cells compared to normal cells (31, 46, 47) and cancer cells most likely rely on WEE1 due to frequent inactivation of TP53 (48–50). Second, we need to determine the relevance of WEE1 regulation by HuR in other tumor types. Third, since HuR translocates to the cytoplasm in response to various DNA damaging agents, it will be important to determine the specific phosphorylation site(s) implicated in the response to these DNA damaging agents. Such insights might lead to new therapeutic strategies (e.g., kinase inhibitors) against chemotherapy resistance. Finally, future studies will determine if this pathway is equally relevant for both acute and acquired drug resistance mechanisms.

HuR’s regulation of WEE1 may be a survival mechanism by PDA cells in the face of acute fluctuations in the tumor microenvironment (33), including chemotherapy exposure. Thus, targeting the molecular interaction between HuR and WEE1 represents a novel opportunity to enhance outcomes in patients receiving the current ‘best available’ treatments (e.g. FOLFIRINOX). Designing therapies that inactivate ‘moving targets’ such as HuR and its regulation of mRNAs such as WEE1 may turn out to be more successful therapeutic strategies than the ongoing attempts of targeting genetic alterations in PDA cells. Specifically, this study along with others may lead us to sequencing and targeting non-exonic areas (e.g., HuR binding sites) of the genome in an effort to enhance current treatment strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant from the AACR-PanCAN grant # 10-20-25-BROD, ACS grant # RSG-10-119-01-CDD, and grants from the WW Smith Foundation (C1004 and C1104) to J.B. This work was also, in part, supported from resources provided by the “Fund a Cure for Pancreatic Cancer” project.

Footnotes

Disclosure: These authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose regarding this manuscript.

References

- 1.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science (New York, NY. 2008;321(5897):1801–1806. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus Gemcitabine for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(19):1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nature reviews. 2003;3(3):155–168. doi: 10.1038/nrc1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarden RI, Pardo-Reoyo S, Sgagias M, Cowan KH, Brody LC. BRCA1 regulates the G2/M checkpoint by activating Chk1 kinase upon DNA damage. Nature genetics. 2002;30(3):285–289. doi: 10.1038/ng837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou BSaL. Single-Stranded DNA Orchestrates an ATM-to-ATR Switch at DNA Breaks. Mol Cell March. 2009;13(33(5)):547–558. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bargonetti J, Manfredi JJ. Multiple roles of the tumor suppressor p53. Current opinion in oncology. 2002;14(1):86–91. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal ML, Agarwal A, Taylor WR, Stark GR. p53 controls both the G2/M and the G1 cell cycle checkpoints and mediates reversible growth arrest in human fibroblasts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1995;92(18):8493–8497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinhardt HC, Aslanian AS, Lees JA, Yaffe MB. p53-deficient cells rely on ATM- and ATR-mediated checkpoint signaling through the p38MAPK/MK2 pathway for survival after DNA damage. Cancer cell. 2007;11(2):175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindqvist AR-BV, Medema RH. The decision to enter mitosis: feedback and redundancy in the mitotic entry network. The Journal of cell biology. 2009;185:193–202. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200812045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sørensen CS, Syljuåsen RG. Safeguarding genome integrity: the checkpoint kinases ATR, CHK1 and WEE1 restrain CDK activity during normal DNA replication. Nucleic acids research. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mueller PRCT, Kumagai A, Dunphy WG. Myt1: a membrane-associated inhibitory kinase that phosphorylates Cdc2 on both threonine-14 and tyrosine-15. Science. 1995;270:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5233.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nobumoto Watanabe MBaTH. Regulation of the human WEE1Hu CDK tyrosine 15-kinase during the cell cycle. The EMBO Journal. 1995;14(9):1878–1891. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07180.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe N, Arai H, Iwasaki J-i, Shiina M, Ogata K, Hunter T, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) phosphorylation destabilizes somatic Wee1 via multiple pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(33):11663–11668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500410102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masuda H, Fong CS, Ohtsuki C, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y. Spatiotemporal regulations of Wee1 at the G2/M transition. Molecular biology of the cell. 2011;22(5):555–569. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mir SE, De Witt Hamer PC, Krawczyk PM, Balaj L, Claes A, Niers JM, et al. In Silico Analysis of Kinase Expression Identifies WEE1 as a Gatekeeper against Mitotic Catastrophe in Glioblastoma. Cancer cell. 2010;18(3):244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe N, Arai H, Nishihara Y, Taniguchi M, Watanabe N, Hunter T, et al. M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCFβ-TrCP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(13):4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith ASS, Fallahi M, Ayad NG. Redundant ubiquitin ligase activities regulate wee1 degradation and mitotic entry. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2795–2799. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.22.4919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayad NG, Rankin S, Murakami M, Jebanathirajah J, Gygi S, Kirschner MW. Tome-1, a Trigger of Mitotic Entry, Is Degraded during G1 via the APC. Cell. 2003;113(1):101–113. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owens L, Simanski S, Squire C, Smith A, Cartzendafner J, Cavett V, et al. Activation Domain-dependent Degradation of Somatic Wee1 Kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(9):6761–6769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ovejero S, Ayala P, Bueno A, Sacristán MP. Human Cdc14A regulates Wee1 stability by counteracting CDK-mediated phosphorylation. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2012;23(23):4515–4525. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-04-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magnussen GI, Holm R, Emilsen E, Rosnes AKR, Slipicevic A, Flørenes VA. High Expression of Wee1 Is Associated with Poor Disease-Free Survival in Malignant Melanoma: Potential for Targeted Therapy. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e38254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bridges KA, Hirai H, Buser CA, Brooks C, Liu H, Buchholz TA, et al. MK-1775, a Novel Wee1 Kinase Inhibitor, Radiosensitizes p53-Defective Human Tumor Cells. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(17):5638–5648. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirai H, Iwasawa Y, Okada M, Arai T, Nishibata T, Kobayashi M. Small-molecule inhibition of Wee1 kinase by MK-1775 selectively sensitizes p53-deficient tumor cells to DNA-damaging agents. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2009;8:2992–3000. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajeshkumar NV, De Oliveira E, Ottenhof N, Watters J, Brooks D, Demuth T, et al. MK-1775, a Potent Wee1 Inhibitor, Synergizes with Gemcitabine to Achieve Tumor Regressions, Selectively in p53-Deficient Pancreatic Cancer Xenografts. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(9):2799–2806. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murrow L, Garimella S, Jones T, Caplen N, Lipkowitz S. Identification of WEE1 as a potential molecular target in cancer cells by RNAi screening of the human tyrosine kinome. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2010;122(2):347–357. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0571-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aarts M, Sharpe R, Garcia-Murillas I, Gevensleben H, Hurd MS, Shumway SD, et al. Forced Mitotic Entry of S-Phase Cells as a Therapeutic Strategy Induced by Inhibition of WEE1. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(6):524–539. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrassa L, Chilà R, Lupi M, Ricci F, Celenza C, Mazzoletti M, et al. Combined inhibition of Chk1 and Wee1: In vitro synergistic effect translates to tumor growth inhibition in vivo. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(13):2507–2517. doi: 10.4161/cc.20899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krajewska M, Heijink AM, Bisselink YJWM, Seinstra RI, Sillje HHW, de Vries EGE, et al. Forced activation of Cdk1 via wee1 inhibition impairs homologous recombination. Oncogene. 2012 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional regulation of cancer traits by HuR. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. 2010;1(2):214–229. doi: 10.1002/wrna.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopez de Silanes I, Zhan M, Lal A, Yang X, Gorospe M. Identification of a target RNA motif for RNA-binding protein HuR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(9):2987–2992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costantino CL, Witkiewicz AK, Kuwano Y, Cozzitorto JA, Kennedy EP, Dasgupta A, et al. The role of HuR in gemcitabine efficacy in pancreatic cancer: HuR Up-regulates the expression of the gemcitabine metabolizing enzyme deoxycytidine kinase. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4567–4572. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pineda DRD, Valley C, Cozzitorto J, Burkhart R, Leiby B, Winter J, Weber M, Londin E, Rigoutsos I, Yeo C, Gorospe M, Witkiewicz A, Sachs J, Brody J. HuR’s post-transcriptional regulation of death receptor 5 in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:946–955. doi: 10.4161/cbt.20952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burkhart RA, Pineda DM, Chand SN, Romeo C, Londin ER, Karoly ED, et al. HuR is a post-transcriptional regulator of core metabolic enzymes in pancreatic cancer. RNA biology. 2013;10(8):1312–1323. doi: 10.4161/rna.25274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomasz MPY. The mitomycin bioreductive antitumor agents: cross-linking and alkylation of DNA as the molecular basis of their activity. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;76:73–87. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonner WM, Redon CE, Dickey JS, Nakamura AJ, Sedelnikova OA, Solier S, et al. [gamma]H2AX and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(12):957–967. doi: 10.1038/nrc2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Heijden MS, Brody JR, Gallmeier E, Cunningham SC, Dezentje DA, Shen D, et al. Functional defects in the fanconi anemia pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. The American journal of pathology. 2004;165(2):651–657. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63329-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hostetter CLL, Costantino C, Witkiewicz A, Yeo C, Brody J, Keen J. Cytoplasmic accumulation of the RNA binding protein HuR is central to tamoxifen resistance in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2008;7:1496–1506. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.9.6490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HH, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. Regulation of HuR by DNA Damage Response Kinases. Journal of Nucleic Acids. 2010;2010 doi: 10.4061/2010/981487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kishore S, Jaskiewicz L, Burger L, Hausser J, Khorshid M, Zavolan M. A quantitative analysis of CLIP methods for identifying binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nature methods. 8(7):559–564. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lebedeva S, Jens M, Theil K, Schwanhausser B, Selbach M, Landthaler M, et al. Transcriptome-wide analysis of regulatory interactions of the RNA-binding protein HuR. Molecular cell. 43(3):340–352. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mukherjee N, Corcoran DL, Nusbaum JD, Reid DW, Georgiev S, Hafner M, et al. Integrative regulatory mapping indicates that the RNA-binding protein HuR couples pre-mRNA processing and mRNA stability. Molecular cell. 43(3):327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell P, Nurse P. Negative regulation of mitosis by wee1+, a gene encoding a protein kinase homolog. Cell. 1987;49(4):559–567. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirai H, Arai T, Okada M, Nishibata T, Kobayashi M, Sakai N, et al. MK-1775, a small molecule Wee1 inhibitor, enhances anti-tumor efficacy of various DNA-damaging agents, including 5-fluorouracil. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2010;9(7):514–522. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.7.11115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guertin AD, Li J, Liu Y, Hurd MS, Schuller AG, Long B, et al. Preclinical Evaluation of the WEE1 Inhibitor MK-1775 as Single Agent Anticancer Therapy. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2013 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim HH, Abdelmohsen K, Lal A, Pullmann R, Jr, Yang X, Galban S, et al. Nuclear HuR accumulation through phosphorylation by Cdk1. Genes & development. 2008;22(13):1804–1815. doi: 10.1101/gad.1645808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopez de Silanes I, Fan J, Yang X, Zonderman AB, Potapova O, Pizer ES, et al. Role of the RNA-binding protein HuR in colon carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22(46):7146–7154. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richards NG, Rittenhouse DW, Freydin B, Cozzitorto JA, Grenda D, Rui H, et al. HuR status is a powerful marker for prognosis and response to gemcitabine-based chemotherapy for resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients. Annals of surgery. 2010;252(3):499–505. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f1fd44. discussion -6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hruban RH, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Wilentz RE, Goggins M, Kern SE. Molecular pathology of pancreatic cancer. Cancer journal (Sudbury, Mass. 2001;7(4):251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kern SE. p53: tumor suppression through control of the cell cycle. Gastroenterology. 1994;106(6):1708–1711. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Redston MS, Caldas C, Seymour AB, Hruban RH, da Costa L, Yeo CJ, et al. p53 mutations in pancreatic carcinoma and evidence of common involvement of homocopolymer tracts in DNA microdeletions. Cancer research. 1994;54(11):3025–3033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.