Abstract

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) frequently have an activating mutation in the gene encoding Janus kinase 2 (JAK2). Thus, targeting the pathway mediated by JAK and its downstream substrate, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), may yield clinical benefit for patients with MPNs containing the JAK2V617F mutation. Although JAK inhibitor therapy reduces splenomegaly and improves systemic symptoms in patients, this treatment does not appreciably reduce the number of neoplastic cells. To identify potential mechanisms underlying this inherent resistance phenomenon, we performed pathway-centric, gain-of-function screens in JAK2V617F hematopoietic cells and found that the activation of the guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) RAS or its effector pathways (mediated by the kinases AKT and ERK) renders cells insensitive to JAK inhibition. Resistant MPN cells became sensitized to JAK inhibitors when also exposed to inhibitors of the AKT or ERK pathways. Mechanistically, in JAK2V617F cells a JAK2-mediated inactivating phosphorylation of the pro-apoptotic protein BAD [B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2)-associated death promoter] promoted cell survival. In sensitive cells, exposure to a JAK inhibitor resulted in dephosphorylation of BAD, enabling BAD to bind and sequester the pro-survival protein BCL-XL (also known as BCL2-like 1), thereby triggering apoptosis. In resistant cells, RAS effector pathways maintained BAD phosphorylation in the presence of JAK inhibitors, yielding a specific dependence on BCL-XL for survival. BCL-XL inhibitors potently induced apoptosis in JAK inhibitor-resistant cells. In patients with MPNs, activating mutations in RAS co-occur with the JAK2V617F mutation in the malignant cells, suggesting that RAS effector pathways likely play an important role in clinically observed resistance.

Introduction

In 2005, a recurrent somatic point mutation in the pseudokinase domain of the Janus kinase 2 gene (JAK2) was discovered in a large proportion of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms [MPNs,(1–3)], a class of hematologic malignancies arising from hematopoietic progenitors that includes acute and chronic myeloid leukemias, polycythaemia vera, essential thrombocythaemia, and primary myelofibrosis. The prevalence of the JAK2V617F mutation and the subsequent finding that these malignancies are dependent upon constitutive Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling prompted strong interest in targeting JAK2 in these patients, leading to the development of several JAK catalytic inhibitors, such as TG101348 (SAR302503), INCB018424 (Ruxolitinib), and CYT387 (4–6). In clinical studies, JAK inhibitors were found to produce palliative effects associated with decreased inflammatory cytokine abundance and reduced splenomegaly but were unable to reverse the disease by decreasing the malignant clone burden (7, 8).

The inability of JAK inhibitor therapy to reduce or eliminate the MPN clone may be caused by a number of factors, including: (i) second site mutations in the JAK2 kinase domain which block effective drug binding to its target (9); (ii) the reactivation of JAK/-STAT signaling in the presence of JAK inhibitors, for example through the heterodimerization of JAK2 with JAK1 or non-receptor tyrosine-protein kinase 2 (TYK2), (10); and (iii) the activation of compensatory signaling pathways which enable malignant cells to circumvent the toxic effects of JAK inhibition. Informative studies were recently conducted to examine options (i) and (ii) above, indicating that these mechanisms may contribute to the resistance observed in some patients. However, despite considerable evidence that compensatory signaling pathways can contribute to resistance to anticancer drugs, including kinase targeted therapies (11–14), no studies have systematically assessed the potential roles of such pathways in the resistance of MPNs to JAK inhibitors.

Thus, we investigated the potential role of compensatory pathways using gain-of-function screens in JAK2V617F–positive cell lines to uncover new therapeutic strategies for refractory disease.

Results

RAS signaling activation confers resistance to JAK inhibition

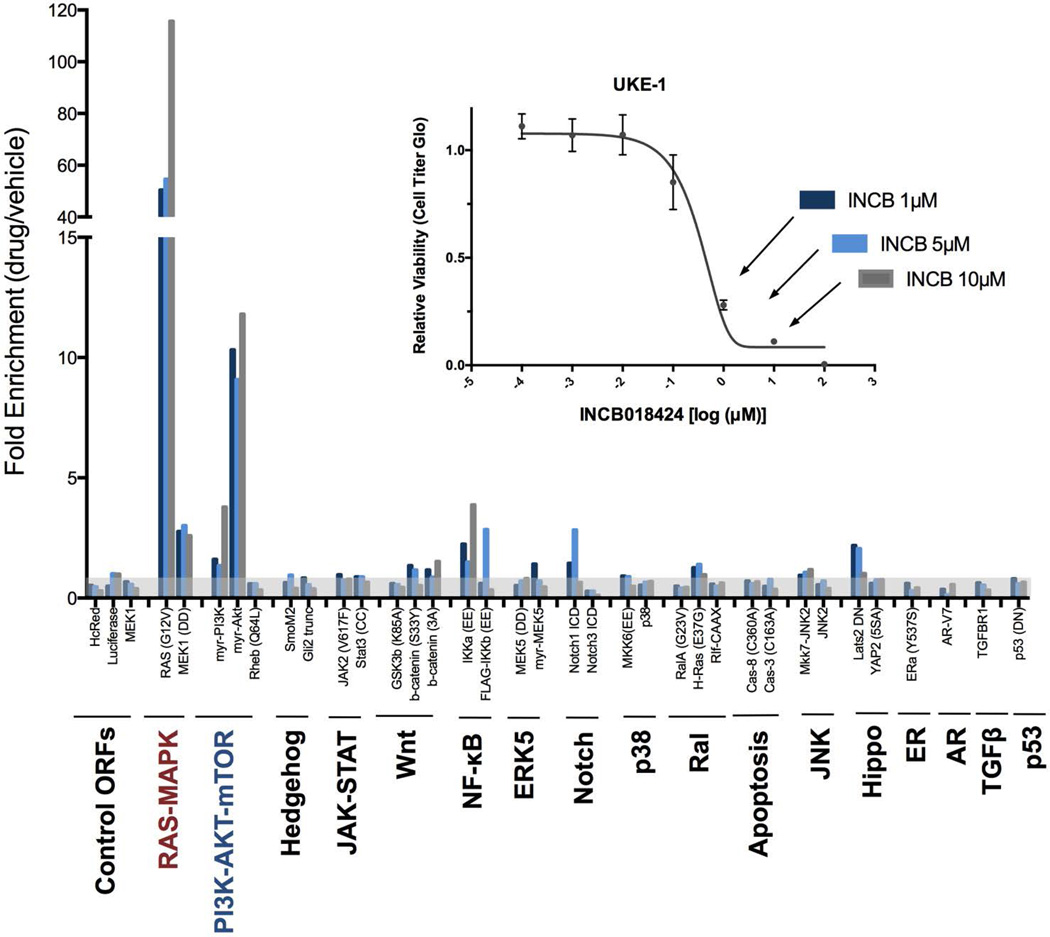

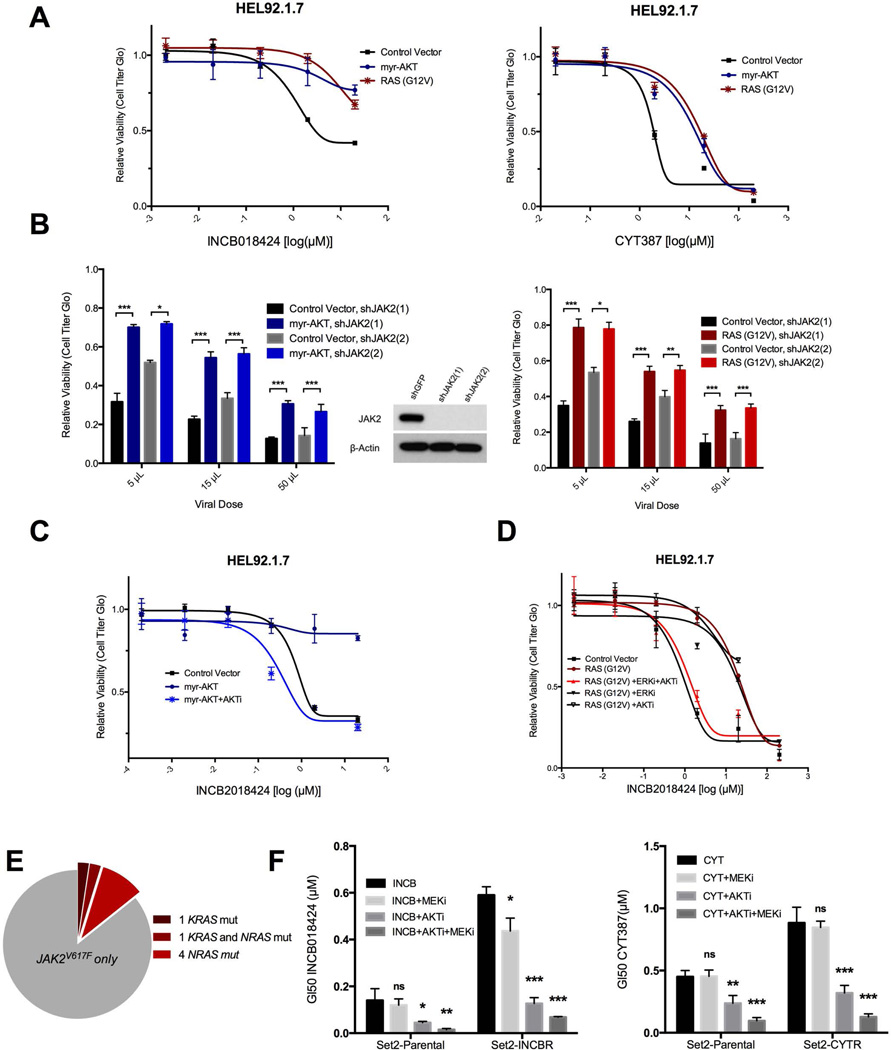

Using constructs that encode constitutively active mutants, 17 oncogenic signaling pathways (table S1) were screened in JAK2V617F UKE-1 cells to identify those pathways capable of driving resistance to the JAK inhibitor INCB018424 (INCB). Screens were performed using low multiplicity of infection (MOI) conditions to ensure that only a single transgene was introduced into each cell. Further, the moderate-strength PGK promoter was used to minimize the likelihood of superphysiological pathway activation caused by overexpression (15). Two constructs — myristolated-AKT (myr-AKT) and RAS-G12V — scored as strong hits (Fig. 1), consistently enriched in the screens by greater than 10- and 50-fold, respectively. Our recent study involving 110 similar drug-modifier screens spanning diverse drugs and cancer types found that enrichment of a hit by greater than 10-fold is rare (14). In GI50 (50% growth inhibition) validation assays, the activation of AKT and RAS resulted in 10- to 50-fold shifts in the GI50 concentrations of two different JAK inhibitors [INCB and CYT387 (CYT)] in two additional JAK2V617F-positive cell lines (HEL92.1.7 and Set2), thus confirming the potential of these pathways to drive resistance when abnormally activated (Fig. 2A and fig. S1). Separately, AKT and RAS activation also conferred resistance to the direct knockdown of JAK2 by two independent short hairpin RNA (shRNA) constructs (Fig. 2B), suggesting that, unlike the recently reported phenomenon of heterodimerization between JAK2-JAK1 or JAK2-TYK2 (10), AKT- and RAS-mediated resistance can operate independently of JAK2 expression. Constructs from the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and Notch pathways also scored weakly in the primary screen (~3 fold enrichment; Fig. 1) but failed to confer robust resistance to INCB in subsequent GI50 validation assays (fig. S2).

Fig. 1. Pathway-activating ORF screen reveals potential modes of resistance to JAK inhibition.

UKE-1 cells (JAK2V617F) were transduced with a pooled lentiviral library and cultured in the presence of three different lethal concentrations of INCB018424 (inset) or vehicle. Bars show the fold increase in the representation of each construct in the INCB-treated samples relative to vehicle-treated samples. Transparent grey shading marks the threshold fold-enrichment score of 1.0. A full list of the constructs used in this library is available in table S1.

Fig. 2. The RAS effector pathways AKT and ERK drive resistance to JAK inhibitors.

(A) Cell viability of HEL92.1.7 cells expressing myr-AKT or RAS-G12V and treated with the indicated concentrations of INCB018424 or CYT387. (B) The relative viability of either control or myr-AKT expressing HEL92.1.7 cells transduced with independent JAK2 shRNAs at three viral doses. (C and D) Relative proliferation of HEL92.1.7 cells expressing myr-AKT (C) or RAS-G12V (D) and treated with INCB alone or in combination with MK2206 (AKTi) and/or VX-11E (ERKi). (E) Coincident RAS mutations in isolated cells from 42 JAK2V617F-positive MDS/MPN patients. (F) GI50 in parental or drug-resistant Set2 cells, treated with INCB or CYT alone or in combination with AKTi and/or MEKi (AZD6244). Data are means ± SD (A, C, D, and F) or SEM (B) of three experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Student’s t test.

RAS effector pathways through AKT and MEK-ERK mediate resistance to JAK inhibitors

Both AKT and RAS mutant constructs are activators of RAS effector pathways, a diverse set of pathways that have been implicated extensively in cell proliferation and survival processes downstream of activated RAS (16). To better understand which particular effector pathways control AKT- and RAS-mediated resistance in JAK2V617F cells, we sought to reverse resistance in these cells using small-molecule inhibitors. Sensitization to INCB in myr-AKT-expressing cells could be fully restored with an allosteric AKT inhibitor, MK-2206 (Fig. 2C), but not with the dual phosphoinostitide 3- kinase (PI3K)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor BEZ-235 (fig. S3), suggesting that resistance in these cells does not depend on AKT-mediated mTOR activation. RAS-G12V-expressing cells could be re-sensitized by dual inhibition of the ERK and AKT effector pathways [using the mitogen-activated protein kinase 2 (ERK 2) inhibitor VX-11E or the AKT inhibitor MK-2206, respectively], but not by inhibition of either pathway alone (Fig. 2D), suggesting that RAS-driven resistance involves the concerted activation of these two effector pathways.

To investigate the potential clinical relevance of JAK inhibitor resistance mediated by RAS effector pathways, we first queried a cohort of JAK2V617F-positive myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/MPN patients for coincident activating mutations in KRAS or NRAS (table S2). In a cohort of 42 treatment-naïve patients, six (14.3%) carried mutations in either KRAS or NRAS, with five occurring at canonical activating sites. The cohort also included one patient with activating mutations in both genes (Fig. 2E). For a second set of experiments, we obtained JAK2V617F Set2 cells that had evolved under selective pressure in culture to become resistant to JAK inhibitors CYT (Set2-CYTR) or INCB (Set2-INCBR) (10). As expected, Set2-CYTR and Set2-INCBR cells were resistant to JAK inhibition relative to parental cells (Fig. 2F). AKT inhibition using MK-2206 re-sensitized both Set2-CYTR and Set2-INCBR cells to GI50 values exhibited by parental cells, and co-inhibition of both AKT and ERK effector pathways [the latter using the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinases 1 and 2 (MEK1/2) inhibitor AZD-6244] further sensitized both resistant and parental cells.

Together, these data establish that (i) activation of RAS or RAS effector pathways can confer considerable resistance to JAK inhibitors; (ii) a subset of JAK2V617F-positive patients carry mutations in RAS capable of activating RAS effector signaling; and (iii) resistance in both engineered and evolved JAK inhibitor-resistant cell lines can be reversed by inhibition of RAS effector pathways mediated by AKT or AKT and either MEK or ERK.

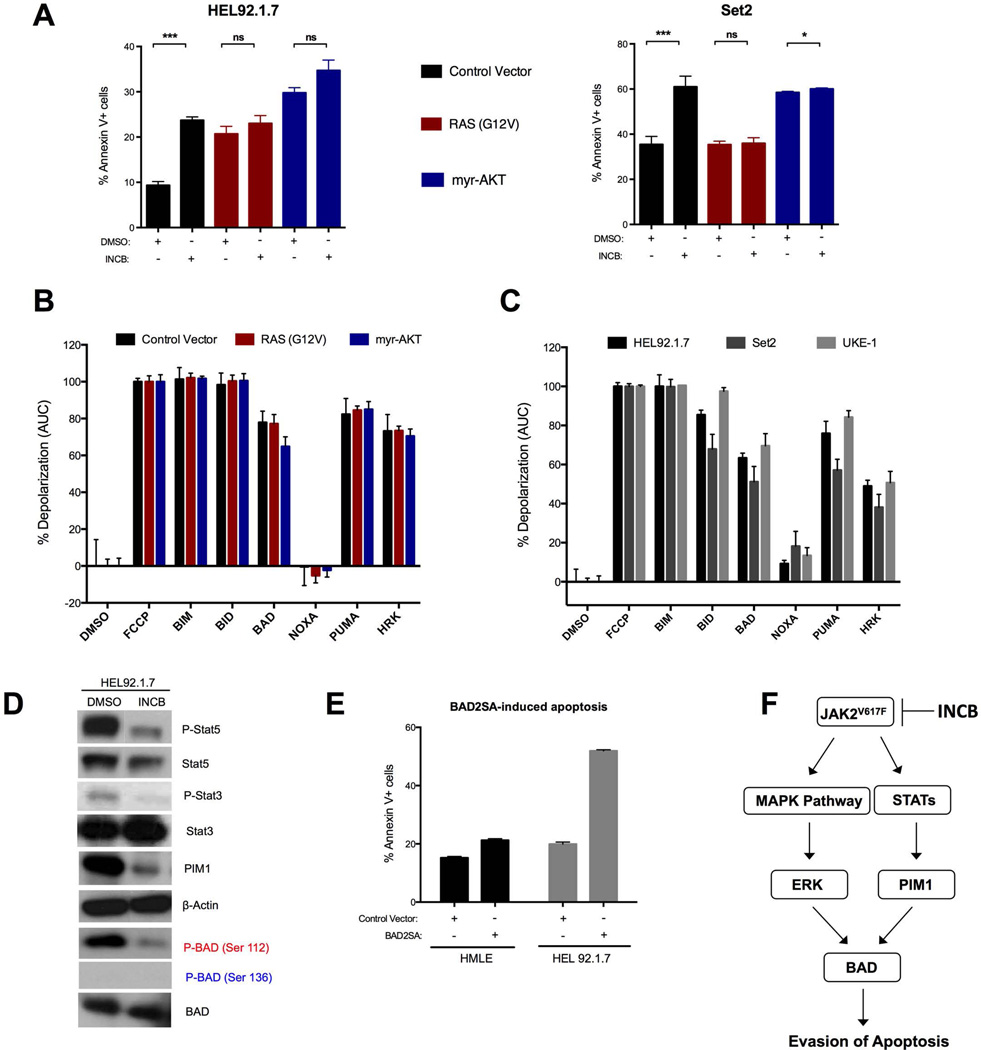

JAK inhibitor-induced apoptosis is normally stimulated by BCL-2-associated death promoter (BAD) in JAK2V617F cells

Whereas parental JAK2V617F cells underwent substantial cell death after INCB treatment, cells expressing constitutively active RAS or AKT did not, suggesting that resistance may involve the suppression of apoptosis. Using Annexin-V staining as a marker of apoptosis, INCB treatment induced apoptosis in multiple JAK2V617F cell lines, but not in cells expressing RAS-G12V or myr-AKT (Fig. 3A). To gain potential insight into the molecular regulation of apoptosis in JAK2V617F cells, we performed BH3 profiling. In this assay, cells are permeabilized, stained with a mitochondrial-potential sensitive dye, and treated with peptides derived from the BH3 domains of pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins. In our study, we used peptides representing the activator BH3-only proteins: B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2)-like protein 11 (BIM) and BH3-interacting domain death agonist (BID); as well as the sensitizer BH3-only proteins: BAD, PUMA (also known as BCL-2-binding component 3), NOXA (also known as phorbol-12-myrisate-13-acetate-induced protein 1), and HRK (harakiri, BCL-2 interacting protein). Sensitizer BH3 peptides representing the full-length proteins listed above can bind and inactivate specific anti-apoptotic proteins to indirectly trigger mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), leading to mitochondrial depolarization in cells dependent on those proteins (17–19). Thus, BH3 profiling can measure overall priming for apoptosis (20) or identify dependence on specific anti-apoptotic proteins. In our experiments, mitochondria from parental and resistant HEL92.1.7 cells were capable of undergoing apoptosis, demonstrated by their response to the BIM and BID peptides, and were equally primed for apoptosis, evident by extensive depolarization induced by the PUMA peptide (which can bind and inactivate all of the major anti-apoptotic proteins), as well as BAD and HRK peptides (which bind either BCL-2 and BCL-XL or only BCL-XL, respectively) (Fig. 3B and fig. S4), suggesting a potential dependence specifically on BCL-XL for survival (18, 21). We then profiled all three lines (HEL92.1.7, Set2, and UKE-1) and confirmed that this pattern was consistent across multiple JAK2V617F cells (Fig. 3C).

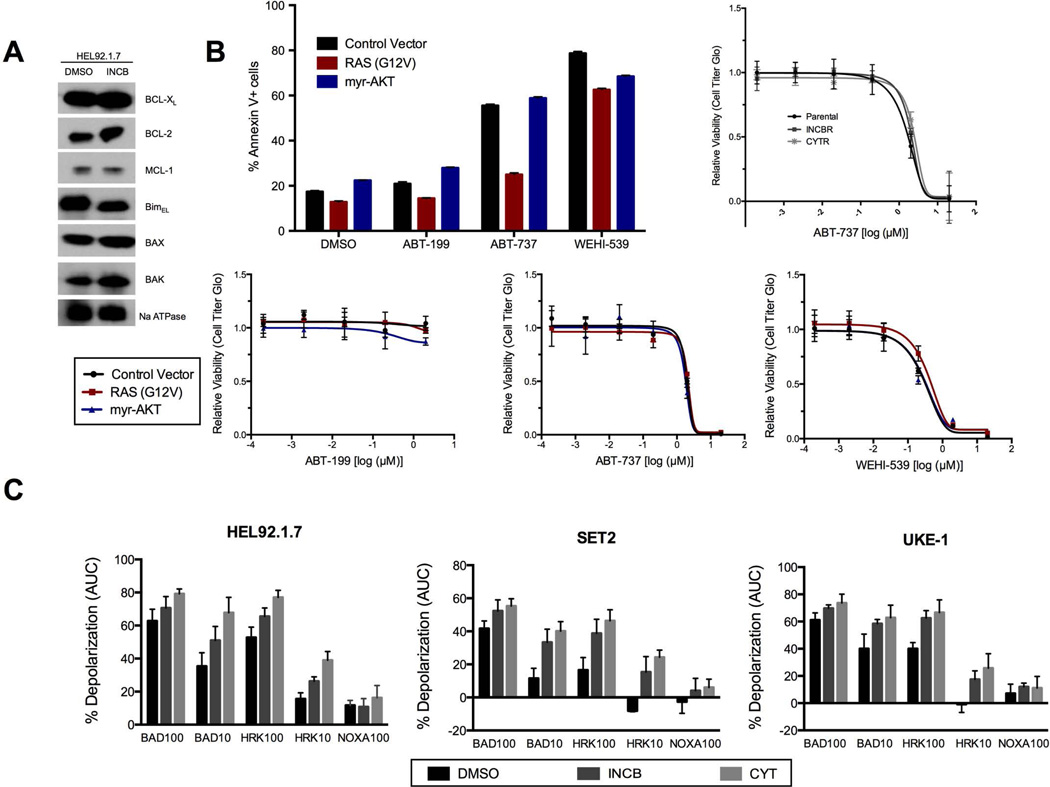

Fig. 3. RAS effector pathway activation rescues JAK inhibitor-induced apoptosis and BH3-profiling suggests BAD as a key gatekeeper to apoptosis in JAK2V617F positive cells.

(A) Apoptosis assays in HEL92.1.7 and Set2 cells transduced with the indicated constructs, treated with INCB, and stained with 7AAD and Annexin V at 72 and 24 hours post drug treatment, respectively. (B) Mitochondrial depolarization of digitonin-permeabilized HEL92.1.7 cells transduced with the indicated constructs, stained with the mitochondrial potential-sensitive JC1 dye, and treated with a panel of BH3 peptides. Percent depolarization is shown as the area under the curve (AUC) normalized to positive control fully depolarized mitochondria (FCCP). DMSO serves as the negative control. C Same as in (B) except in this case the indicated JAK2V617F positive cell lines were profiled. D Western blot analysis of HEL92.1.7 cells immunoblotted as indicated after treatment with INCB for 6 hours. Blots are representative of three replicate experiments. E Analysis of apoptosis induction in HMLE and HEL92.1.7 cells as in (A) 24 hours after transduction with the indicated ORF. F A model depicting the putative signaling axis downstream of mutant JAK2. Data are means ± SD of three experiments. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 by Student’s t test.

The pro-apoptotic function of BAD is known to be inhibited by phosphorylation at either Ser112 or Ser136 by a number of kinases (22–25). Two of these kinases, the serine/threonine kinase PIM1 and ERK, which both phosphorylate BAD at Ser112 (23, 25, 26) are stimulated by JAK–STAT signaling (10, 27). Consistent with this, we found that PIM1 expression was inhibited by JAK2 inhibition (Fig. 3D and fig. S5A). Additionally, to effectively phenocopy the reduction of Ser112-phosphorylated BAD conferred by JAK inhibition, it was necessary to inhibit both ERK and PIM1 (fig. S5B). Further, in apoptosis assays, ERK inhibition alone had no detectable affect, whereas PIM1 inhibition induced apoptosis, although to a lesser extent than did direct JAK inhibition (fig. S5C). Combined inhibition of PIM1 and ERK yielded a greater-than-additive effect, resulting in a higher amount of apoptosis than that induced by direct JAK inhibition. These data demonstrate that the relevant BAD kinases in the setting of normally proliferating JAK2V617F cells are likely ERK and PIM1. To functionally verify that BAD phosphorylation is critical to apoptosis in JAK2V617F cells, we transduced HEL92.1.7 cells with either a control vector or a double Ser-to-Ala murine BAD mutant called BAD2SA, which cannot be phosphorylated at sites Ser112 and Ser136 (22, 23, 28). BAD2SA expression in HEL92.1.7 cells induced apoptosis that was comparable to JAK or PIM1+ERK inhibition (Fig. 3E), whereas the expression of BAD2SA in HMLE cells, a control cell line that is insensitive to BAD-induced apoptosis, had an expectedly negligible effect on apoptosis (Fig. 3E and fig. S6). Together, these results support a model wherein BAD phosphorylation inhibits apoptosis and survival downstream of JAK2 and PIM1/ERK in JAK2V617F-positive cells (Fig. 3F).

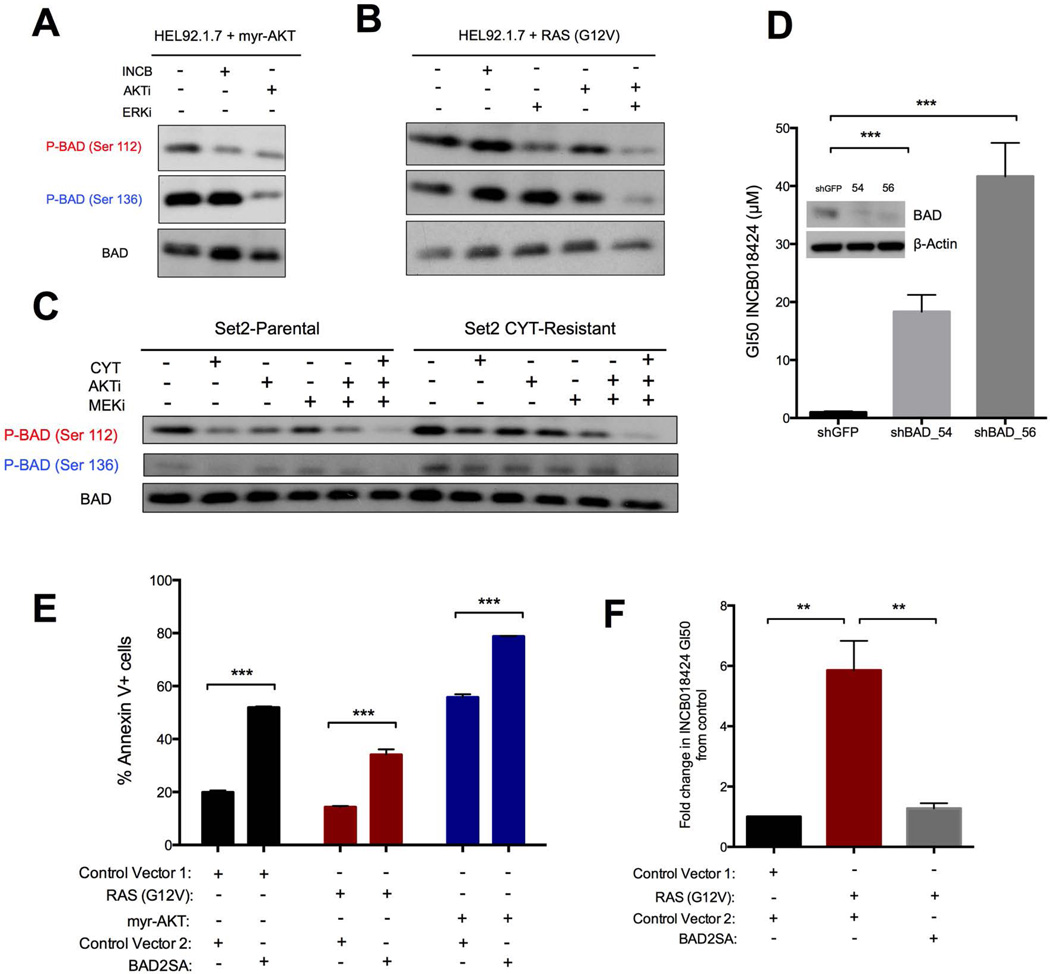

RAS effector pathways drive resistance by blocking BAD-induced apoptosis

Activation of the RAS effector pathways AKT and ERK leads to inhibitory phosphorylation of BAD at Ser136 and Ser112, respectively, independently of PIM1 (22, 25). We therefore hypothesized that resistance to JAK inhibition by RAS effector pathways may be mediated through the phosphorylation of BAD. To test this, we examined BAD phosphorylation in cells expressing constitutively active AKT or RAS in the presence of INCB. In cells expressing active AKT, the phosphorylation of Ser112 was lost whereas Ser136 phosphorylation was unaffected by the presence of INCB; however, it ultimately decreased in the presence of an AKT inhibitor (Fig. 4A). In cells expressing RAS-G12V, neither Ser112 nor Ser136 phosphorylation was decreased by INCB or an AKT inhibitor, whereas both were decreased by combined treatment with AKT and ERK pathway inhibitors (Fig. 4B). Similarly, BAD was phosphorylated at Ser112 in parental Set2 cells, and this phosphorylation was sensitive to JAK inhibition by CYT (Fig. 4C). Conversely, in independently evolved CYT-resistant Set2 cells, BAD was phosphorylated at both Ser112 and Ser136. The phosphorylation at both sites was not lost in CYT-resistant cells in the presence of the inhibitor (Fig. 4C), compared with nearly complete abrogation in the presence of combined inhibition of JAK, AKT, and the ERK pathways (Fig. 4C). In sum, these data demonstrate that activation of the RAS effector pathways AKT and ERK promotes the inhibitory phosphorylation of BAD despite the presence of JAK inhibitors in both engineered and evolved JAK inhibitor-resistant cells.

Fig. 4. BAD activity, regulated by its phosphorylation status at Ser112 and Ser136, dictates drug sensitivity and apoptosis induction in both the drug-sensitive and drug-resistant states.

(A–C) Western blotting in protein lysates from myr-AKT-transduced HEL92.1.7 (A), RAS(G12V)-transduced HEL92.1.7 (B), Set2-Parental, or Set2-CYTR (C) cells 6 hours after treatment with the specified drugs. Blots are representative of three experiments. (D) INCB GI50 values for HEL92.1.7 cells expressing the indicated short hairpin vectors. Protein knockdown assessed 72 hours after lentiviral transduction and selection is shown inset. (E, F) Apoptosis assessed by 7AAD and Annexin V staining (E) and fold-change in INCB GI50 (F) in HEL92.1.7 cells stably expressing the indicated ORFs and transduced with a second ORF expressing either a second control vector or BAD2SA. Data are means ± SD of three experiments. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, Student’s t test.

If inactivating phosphorylation of BAD by RAS effector pathways is responsible for the observed resistance, then knockdown of BAD should also confer resistance independently of RAS activation. Indeed, knockdown of BAD by two independent shRNA constructs conferred robust resistance to INCB (JAK inhibitor INCB018424) (Fig. 4D) that phenocopied the desensitization of cells with RAS effector activation (Fig. 2F), suggesting that resistance is mediated through BAD. To further substantiate the role of BAD in resistance, we transfected cells expressing RAS-G12V or myr-AKT with BAD2SA and evaluated its effects on apoptosis. For both resistant HEL derivative cell lines, BAD2SA expression alone was sufficient to induce marked apoptosis, similar to the response observed in the parental cells (Fig. 4E). Finally, to demonstrate that BAD governs sensitivity to JAK inhibitors downstream of RAS effector pathways, we sought to reverse the resistance seen in cells expressing constitutively active AKT or RAS by co-expressing BAD2SA. Cells co-expressing myr-AKT and BAD2SA were unable to survive long enough to complete the GI50 assay, underscoring the importance of BAD in these cells. We were, however, able to preserve a population of cells co-expressing RAS-G12V and BAD2SA. Consistent with a model of resistance driven by the inactivating phosphorylation of BAD by RAS effectors, expression of BAD2SA was sufficient to re-sensitize these cells to JAK inhibitors (Fig. 4F).

BCL-XL is the relevant anti-apoptotic target downstream of JAK and BAD

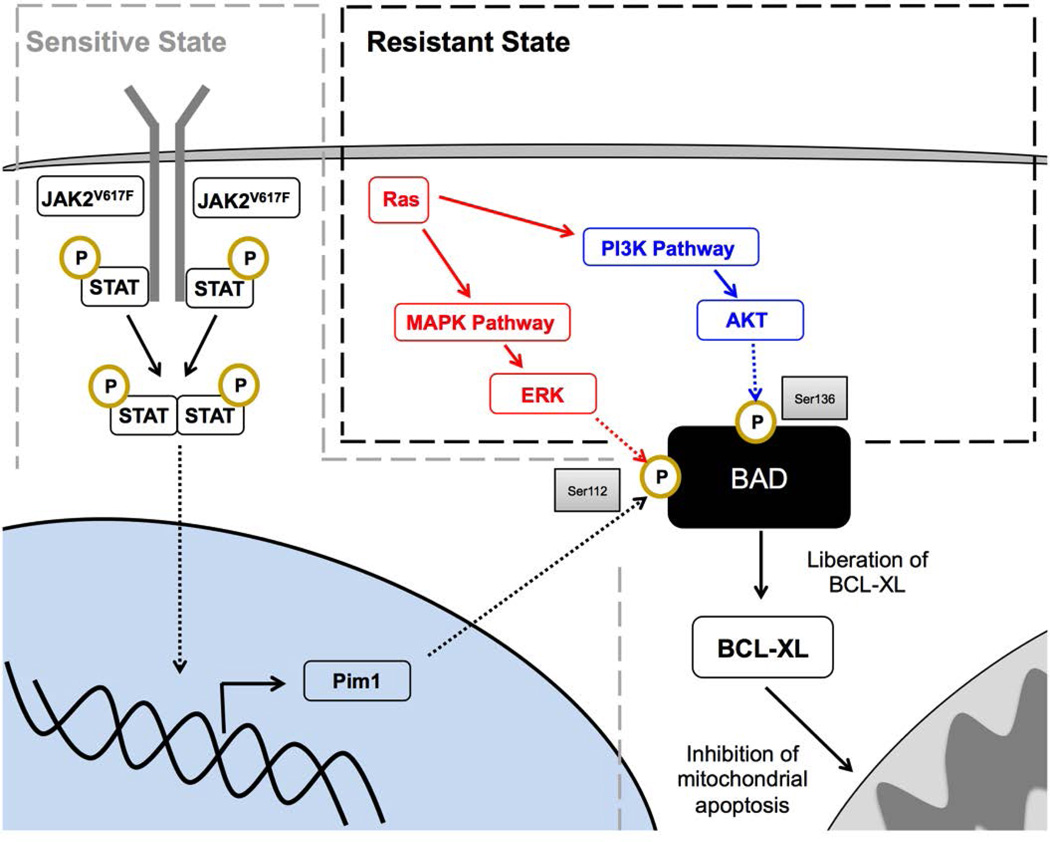

BAD can potentially bind and inactivate BCL-2, BCL-XL, and BCL-2-like protein 2 (BCL-w) (19). HRK is only able to bind BCL-XL. Thus the BH3 profiling results predicted that these cells are specifically dependent upon only BCL-XL (Fig. 3B and C). Immunoblotting of HEL92.1.7 cells showed that BCL-XL was highly expressed compared to the other anti-apoptotic proteins BCL-2 and myeloid cell leukemia 1 (MCL-1) (Fig. 5A); thus, it might be expected that inhibition of BCL-XL would be toxic to these cells. To test this hypothesis, we measured viability and apoptosis in cells treated with ABT-199 (a selective BCL-2 inhibitor), WEHI-539 (a selective BCL-XL inhibitor), and ABT-737 (a dual BCL-2/BCL-XL inhibitor). Parental cells and cells expressing RAS-G12V or myr-AKT were insensitive to ABT-199 but sensitive to both WEHI-539 and ABT-737 (Fig 5B, fig S7). Additionally, independently evolved JAK inhibitor-resistant cells were also equally sensitive to ABT-737 compared with matched parental cells (Fig. 5B). To confirm this BCL-XL dependency downstream of JAK signaling, we examined the effects of JAK inhibition on the BH3 profiles of our JAK2V617F-positive cells. After incubation with two different JAK inhibitors for 8 hours, all three lines showed increased sensitivity to titrations of both the BAD and HRK peptides (Fig. 5C), suggesting that abrogation of BCL-XL occurs downstream of JAK inhibition. The sensitivity to the NOXA peptide (which binds only MCL-1) did not appreciably increase, implying little to no role for MCL-1 in this setting. Collectively, these data support a model in which cell survival in JAK2-driven MPNs relies specifically on the activation state of BAD and its consequent downstream regulation of BCL-XL. Resistance to JAK inhibition can thus be driven by RAS effector-mediated suppression of the BAD/BCL-XL signaling axis, and reciprocally, resistance can be circumvented by either co-inhibition of JAK and the RAS effector pathways AKT and ERK or by direct inhibition of BCL-XL (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. BCL-XL, not BCL-2 or MCL-1, is the key anti-apoptotic effector downstream of JAK and BAD.

(A) Western blot analysis of HEL92.1.7 cells treated with INCB for 6 hours and immunoblotted as shown. Blots are representative of three replicate experiments. B Annexin V-positive HEL92.1.7 ORF-expressing cells after treatment with a selective BCL-2 inhibitor (ABT-199), a selective BCL-XL inhibitor (WEHI-539), or BCL-family inhibitor (ABT-737) for 48 hours. (Below and Right) As in Fig. 2A, the relative proliferation for the indicated HEL92.1.7 derivatives or Set2-Parental, -INCBR, and -CYTR cell lines treated with the specified inhibitors is shown. C BH3-profiling of HEL92.1.7, Set2, and UKE-1 cells as before with slight alterations. Cells were incubated with the indicated JAK inhibitors for 8 hours and then profiled using either 100 µM or 10 µM of the indicated peptide. Data are means ± SD [(B) line graphs, and (C)] or SEM [(B) bar graph] of three experiments.

Fig. 6. A BAD/BCL-XL-centric model governing survival in JAK inhibitor-resistant and sensitive cells.

In the sensitive state (grey dashed line), survival is predominantly controlled by canonical JAK signaling-mediated inactivation of BAD at the Ser112 site. In the resistant state (black dashed line), RAS effector pathways ERK and AKT, driven by activating mutations in RAS or other upstream signals, provide compensatory survival signals at the functionally equivalent Ser112 and Ser136 sites, rescuing the effects of JAK2 inhibition and representing a coalescent signaling node through which survival is orchestrated in JAK2V617F cells.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that the activation of RAS or its effector pathways AKT and ERK can efficiently rescue JAK inhibitor-driven apoptosis in JAK2V617F MPN cells. Rescue was based on the fact that RAS effector pathways and the JAK2-PIM1/ERK pathway can each redundantly phosphorylate and inactivate BAD, the pro-apoptotic protein whose activation status determines survival in these cells. In normally proliferating cells the inhibition of JAK2 lead to dephosphorylation of BAD and its sequestration of the pro-survival protein BCL-XL (22, 24, 29–31). In cells with activated RAS effector pathways, JAK2 inhibition was insufficient to dephosphorylate BAD because of its redundant phosphorylation by the AKT and ERK pathways. These findings suggest that compensatory activation of the AKT and/or ERK pathways may explain the inability of JAK inhibitor monotherapy to reduce the malignant clone burden in JAK2V617F MPN patients, a hypothesis which was supported by both (i) the observation that these RAS effector pathways are hyperactivated in resistant cells (32, 33) and (ii) our finding that co-inhibition of these pathways sensitized resistant cells to JAK inhibitor therapy. Further, while a diverse array of upstream events may potentially lead to the activation of RAS effector pathways to drive resistance (16), including the overexpression or mutational activation of receptor tyrosine kinases, the stimulation of MPN cells with soluble growth factors or cytokines in their microenvironment, or the mutational activation of either the ERK or AKT effector pathways, our evidence suggests that this was achieved in a subset of JAK2V617F MPN patients through direct activating mutations in KRAS or NRAS.

The results presented here unify several recent findings in the field of JAK2V617F positive MPNs. First, a recent study demonstrated that heterodimerization of JAK2 with JAK1 or TYK2 occurs in JAK2V617F cells that are resistant to JAK inhibitors and further hypothesized that this heterodimerization may drive resistance through reactivation of STAT signaling (10). The evidence presented here suggests that resistance in cells with JAK2 heterodimerization may function through the transactivation of Ras effector pathways rather than the reactivation of STAT signaling, as pharmacological inhibition of Ras effector pathways fully re-sensitized these cells in our hands. Second, redundant survival signaling through the JAK/STAT, AKT, and ERK pathways described here provides a mechanistic explanation for the limited activities of monotherapies targeting MEK, PI3K/mTOR, and AKT in both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant JAK2V617F cells despite the constitutive activity of these pathways (32, 34, 35). Third, while a previous study identified a correlation between JAK2/STAT/PIM1 activity and BAD phosphorylation in drug-sensitive cells (36), more recent studies have excluded BAD as a potential regulator of apoptosis by demonstrating that phosphorylation levels at Ser136 are unchanged by JAK inhibitor treatment. The latter study suggested instead that BIM is the key apoptosis regulator in these cells (37). Our results reconcile these discrepancies by demonstrating that BAD phosphorylation at Ser112 is the relevant target of JAK/STAT signaling in drug sensitive cells; that BAD phosphorylation at Ser 112 and 136 by the RAS effectors ERK and AKT, respectively, can rescue JAK inhibitior-induced loss of Ser112 phosphorylation; and finally, that BAD phosphorylation is required for survival and RAS effector-mediated drug resistance. BIM, on the other hand, is necessary for the execution of apoptosis via its efficient activation of BCL-2-associated X protein (BAX) (38), and its knockdown is sufficient to drive resistance to JAK inhibitors (37), but it acts downstream of BAD. Fourth, by demonstrating that survival in both sensitive and resistant cells is dependent on BCL-XL, we provide a mechanistic rationale for the recent findings that (i) JAK2V617F cells show marked insensitivity to BCL-2 inhibition (39) and (ii) combination therapy involving a JAK inhibitor combined with a dual BCL-2/BCL-XL inhibitor (ABT-737) yields improved responses in animal models of JAK2V617F MPN relative to JAK inhibitor monotherapy (32).

Finally, this work suggests that the combined inhibition of JAK2 and RAS effector pathways, or the direct, selective inhibition of BCL-XL, may yield more robust and durable responses in patients than JAK inhibitor monotherapy. In the near term, the former approach may be more tractable, as the direct inhibition of BCL-XL using early-generation inhibitors has been associated with on-target toxicities (40, 41). Generally, however, our studies suggest that therapies based on the combination of JAK inhibitors with (i) AKT inhibitors; (ii) AKT plus MEK or ERK inhibitors; or (iii) selective BCL-XL inhibitors, or monotherapies involving selective BCL-XL inhibitors alone, warrant further preclinical investigation.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and pharmacological agents

All cell lines were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. UKE-1 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal calf serum, 10% horse serum and 1µM hydrocortisone. HEL92.1.7 cells were grown in RPMI with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Set2 cells were grown in RPMI with 20% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Set2-inhibitor resistant (CYTR and INCBR) and control cells (Parental) were grown as above in media supplemented with 0.7µM INCB018424, 0.5µM CYT387, or DMSO respectively. UKE-1 and HEL92.1.7 cells were obtained from Ann Mullally, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Set2 parental and resistant cell lines were obtained from Ross Levine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering. Drugs were purchased from Selleck Chemicals, ChemieTek, and ApexBio and were used at the following concentrations: 2 µM for VX-11E, 10 µM for MK-2206, 2 µM for AZD-6244, 0.2 µM for BEZ-235 (GI50 assay and western blots), 4 µM for SGI-1776 (western blots and apoptosis assays) 1 µM for INCB and CYT (Western blots, BH3 profiling), and 5 µM for INCB, 1.6 µM for ABT-737 and ABT-199, and 0.8 µM for WEHI-539 (apoptosis assays).

Pathway-activating screen

We performed pooled lentiviral screens as previously described (14). UKE-1 cells were infected with the pooled library (MOI = 0.3) and treated separately with either vehicle [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] or three concentrations of INCB018424 (1 µM, 5 µM, and 10 µM). After three weeks of culture, all drug- and vehicle-treated cells were subjected to genomic DNA purification and PCR-based barcode amplification. Results were de-convoluted as previously described using the Illumina Hi-Seq 2000 sequencing platform.

GI50 assay

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates and infected with the desired ORF activating allele or control vector. Lentiviruses were produced and applied as previously described (42). Following two days of puromycin selection (2 µg/ml), infected cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 5,000 cells/well. To generate GI50 curves, cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or an eight-log serial dilution of drug to yield final concentrations of 200, 20, 2, 0.2, 0.02, 0.002, 0.0002, or 0.00002 µM. Each treatment condition was represented by at least three replicates. Three to four days after drug addition, cell viability was measured using Cell Titer Glo® (Promega). Relative viability was then calculated by normalizing luminescence values for each treatment condition to control treated wells. To generate GI50 curves for drug combinations, slight modifications are made. Primary drug was applied and diluted as above while the second drug was kept at a constant concentration across all wells except the DMSO-only condition. Viability for all primary drug dilutions was then calculated relative to luminescence values from the secondary drug-only condition. Dose-response curves were fit using Graph pad/ Prism 6 software.

Western blotting and antibodies

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (42) and membranes were probed with primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution) recognizing p-STAT5, STAT5, p-STAT3, STAT3, BAD, p-BAD Ser112, p-BAD Ser136, p-AKT (Thr308), AKT, p-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), ERK1/2, PIM1, BCL-XL, BCL-2, MCL-1, BIM, BAX, BAK, NaATPase, and β-Actin. All antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

shRNA constructs

TRC shRNA clones were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and the Duke RNAi Facility as glycerol stocks. Constructs were prepared in lentiviral form and used to infect target cells as previously described (43). TRC IDs and hairpin sequences can be found in table S3.

Quantification of apoptosis by Annexin-V

Cells were seeded in six-well plates and treated with either the indicated amount of drug or vehicle (DMSO). Cells were incubated for the indicated time, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and resuspended in 1X Annexin V binding buffer (10mM HEPES, 140mM NaCl, 2.5mM CaCl2; BD Biosciences). Surface exposure of phosphatidylserine was measured using APC-conjugated Annexin V (BD Biosciences). 7-AAD (BD Biosciences) was used as a viability probe. Experiments were analyzed at 20,000 counts/sample using BD FACSVantage SE. Gatings were defined using untreated/unstained cells as appropriate.

qRT-PCR

Real-time PCR was performed as previously described (14). Human PIM1; forward primer 5’-TTATCGACCTCAATCGCGGC-3’; reverse primer 5’-GGTAGCGATGGTAGCGGATC-3’; Human GAPDH; forward primer 5’-CCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGAC-3’; reverse primer 5’-ACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAA-3’.

BH3 profiling

HMLE, Set2, UKE-1 and HEL92.1.7 cells were BH3 profiled as previously described (38).

Phospho-null BAD mutants

Wild-type and double Ser-to-Ala (S112A/S136A) mutant murine BAD constructs were obtained from Addgene and cloned using the Gateway® system (Life Technologies) into the pLX-303 vector and prepared for lentiviral infection as previously described (44).

Patient cohort

The patient cohort consisted of 42 patients. The male to female ratio was 1.8 (27/15). The median age was 75.9 years, ranging from 55.3 to 89.1 years. All patients were diagnosed following the WHO 2008 criteria, including 16 cases with Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), 2 with Myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm, unclassifiable (MDS/MPN, U), 6 with MPN and 18 with Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis (RARS-T). The study design adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by our institutional review board before its initiation.

Mutational analyses

JAK2V617F mutation was analyzed by melting curve analysis, as described in Schnittger et al. (45) NRAS mutations were analyzed either by melting curve analysis described previously (46) or Next-generation deep-sequencing using the 454 GS FLX amplicon chemistry (Roche Applied Science) as previously described (47). In melting curve analysis, positive NRAS cases were subsequently further characterized by Next-generation sequencing. KRAS mutations were either sequenced by the Sanger method or Next-generation deep-sequencing (45, 47).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ross Levine for JAK inhibitor resistant Set2 cells and helpful discussions. We thank Colin Martz, Sara Meyer, Murat Arcasoy, Joanne Dai, Alex Jaeger, and members of the Wood lab for scientific input and technical assistance.

Funding: This work was supported by Duke University start-up funds (K.C.W.), the National Institutes for Health Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program (K.C.W.), the Stewart Trust (K.C.W.), Golfers Against Cancer (K.C.W.), the Speer Memorial Fellowship (P.S.W.), the Duke Medical Scientist Training Program (T32 GM007171 to K.H.L.), the American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship (121360-PF-11-256-01-TBG to K.A.S.), and the National Cancer Institute (NCI 2R01 CA129974 to A.L.).

Footnotes

Author contributions: P.S.W. performed experiments and analyzed data with assistance from K.A.S. (BH3 profiling), K.H.L. (apoptosis analysis), and K.C.W. (primary screens). M.M. and S.S. obtained and genotyped patient samples. All authors contributed to the design of experiments and analysis of results. P.S.W. and K.C.W. wrote the manuscript, and all authors provided editorial input.

Competing financial interests: S.S. declares equity ownership in MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory GmbH. M.M. is employed by MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory GmbH. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data and materials availability: P.S.W. and K.C.W. have filed a preliminary patent with Duke University covering aspects of the work described in this paper. Data for the lentiviral screen are deposited in [DATABASE NAME] ([URL HERE]), accession number [XXXXXXX].

References and Notes

- 1.Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, Teo SS, Tiedt R, Passweg JR, Tichelli A, Cazzola M, Skoda RC. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352:1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Cools J, Ebert BL, Wernig G, Huntly BJ, Boggon TJ, Wlodarska I, Clark JJ, Moore S, Adelsperger J, Koo S, Lee JC, Gabriel S, Mercher T, D'Andrea A, Frohling S, Dohner K, Marynen P, Vandenberghe P, Mesa RA, Tefferi A, Griffin JD, Eck MJ, Sellers WR, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Lee SJ, Gilliland DG. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer cell. 2005;7:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James C, Ugo V, Le Couedic JP, Staerk J, Delhommeau F, Lacout C, Garcon L, Raslova H, Berger R, Bennaceur-Griscelli A, Villeval JL, Constantinescu SN, Casadevall N, Vainchenker W. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434:1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quintas-Cardama A, Vaddi K, Liu P, Manshouri T, Li J, Scherle PA, Caulder E, Wen X, Li Y, Waeltz P, Rupar M, Burn T, Lo Y, Kelley J, Covington M, Shepard S, Rodgers JD, Haley P, Kantarjian H, Fridman JS, Verstovsek S. Preclinical characterization of the selective JAK1/2 inhibitor INCB018424: therapeutic implications for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;115:3109–3117. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-214957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pardanani A, Lasho T, Smith G, Burns CJ, Fantino E, Tefferi A. CYT387, a selective JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor: in vitro assessment of kinase selectivity and preclinical studies using cell lines and primary cells from polycythemia vera patients. Leukemia. 2009;23:1441–1445. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wernig G, Kharas MG, Okabe R, Moore SA, Leeman DS, Cullen DE, Gozo M, McDowell EP, Levine RL, Doukas J, Mak CC, Noronha G, Martin M, Ko YD, Lee BH, Soll RM, Tefferi A, Hood JD, Gilliland DG. Efficacy of TG101348, a selective JAK2 inhibitor, in treatment of a murine model of JAK2V617F-induced polycythemia vera. Cancer cell. 2008;13:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verstovsek S, Kantarjian H, Mesa RA, Pardanani AD, Cortes-Franco J, Thomas DA, Estrov Z, Fridman JS, Bradley EC, Erickson-Viitanen S, Vaddi K, Levy R, Tefferi A. Safety and efficacy of INCB018424, a JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, in myelofibrosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:1117–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardanani A, Gotlib JR, Jamieson C, Cortes JE, Talpaz M, Stone RM, Silverman MH, Gilliland DG, Shorr J, Tefferi A. Safety and efficacy of TG101348, a selective JAK2 inhibitor, in myelofibrosis. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:789–796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.8021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshpande A, Reddy MM, Schade GO, Ray A, Chowdary TK, Griffin JD, Sattler M. Kinase domain mutations confer resistance to novel inhibitors targeting JAK2V617F in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2012;26:708–715. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koppikar P, Bhagwat N, Kilpivaara O, Manshouri T, Adli M, Hricik T, Liu F, Saunders LM, Mullally A, Abdel-Wahab O, Leung L, Weinstein A, Marubayashi S, Goel A, Gonen M, Estrov Z, Ebert BL, Chiosis G, Nimer SD, Bernstein BE, Verstovsek S, Levine RL. Heterodimeric JAK-STAT activation as a mechanism of persistence to JAK2 inhibitor therapy. Nature. 2012;489:155–159. doi: 10.1038/nature11303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong CR, Janne PA. The quest to overcome resistance to EGFR-targeted therapies in cancer. Nature medicine. 2013;19:1389–1400. doi: 10.1038/nm.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glickman MS, Sawyers CL. Converting cancer therapies into cures: lessons from infectious diseases. Cell. 2012;148:1089–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poulikakos PI, Rosen N. Mutant BRAF melanomas--dependence and resistance. Cancer cell. 2011;19:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martz CA, Ottina KA, Singleton KR, Jasper JS, Wardell SE, Peraza-Penton A, Anderson GR, Winter PS, Wang T, Rathmell JC, Wargo JA, McDonnell DP, Sabatini DM, Wood KC. Systematic identification of signalling pathways with potential to confer anticancer drug resistance. Science. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaa1877. In revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin JY, Zhang L, Clift KL, Hulur I, Xiang AP, Ren BZ, Lahn BT. Systematic comparison of constitutive promoters and the doxycycline-inducible promoter. PloS one. 2010;5:e10611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng J, Carlson N, Takeyama K, Dal Cin P, Shipp M, Letai A. BH3 profiling identifies three distinct classes of apoptotic blocks to predict response to ABT-737 and conventional chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer cell. 2007;12:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Certo M, Del Gaizo Moore V, Nishino M, Wei G, Korsmeyer S, Armstrong SA, Letai A. Mitochondria primed by death signals determine cellular addiction to antiapoptotic BCL-2 family members. Cancer cell. 2006;9:351–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Letai AG. Diagnosing and exploiting cancer's addiction to blocks in apoptosis. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2008;8:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrc2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ni Chonghaile T, Sarosiek KA, Vo TT, Ryan JA, Tammareddi A, Moore Vdel G, Deng J, Anderson KC, Richardson P, Tai YT, Mitsiades CS, Matulonis UA, Drapkin R, Stone R, Deangelo DJ, McConkey DJ, Sallan SE, Silverman L, Hirsch MS, Carrasco DR, Letai A. Pretreatment mitochondrial priming correlates with clinical response to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Science. 2011;334:1129–1133. doi: 10.1126/science.1206727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan JA, Brunelle JK, Letai A. Heightened mitochondrial priming is the basis for apoptotic hypersensitivity of CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:12895–12900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914878107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, Greenberg ME. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonni A, Brunet A, West AE, Datta SR, Takasu MA, Greenberg ME. Cell survival promoted by the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway by transcription-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Science. 1999;286:1358–1362. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer SJ. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-X(L) Cell. 1996;87:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang X, Yu S, Eder A, Mao M, Bast RC, Jr, Boyd D, Mills GB. Regulation of BAD phosphorylation at serine 112 by the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Oncogene. 1999;18:6635–6640. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aho TL, Sandholm J, Peltola KJ, Mankonen HP, Lilly M, Koskinen PJ. Pim-1 kinase promotes inactivation of the pro-apoptotic Bad protein by phosphorylating it on the Ser112 gatekeeper site. FEBS letters. 2004;571:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine RL, Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Gilliland DG. Role of JAK2 in the pathogenesis and therapy of myeloproliferative disorders. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2007;7:673–683. doi: 10.1038/nrc2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.She QB, Solit DB, Ye Q, O'Reilly KE, Lobo J, Rosen N. The BAD protein integrates survival signaling by EGFR/MAPK and PI3K/Akt kinase pathways in PTEN-deficient tumor cells. Cancer cell. 2005;8:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelekar A, Chang BS, Harlan JE, Fesik SW, Thompson CB. Bad is a BH3 domain-containing protein that forms an inactivating dimer with Bcl-XL. Molecular and cellular biology. 1997;17:7040–7046. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheid MP, Schubert KM, Duronio V. Regulation of bad phosphorylation and association with Bcl-x(L) by the MAPK/Erk kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:31108–31113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.31108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang E, Zha J, Jockel J, Boise LH, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Bad, a heterodimeric partner for Bcl-XL and Bcl-2, displaces Bax and promotes cell death. Cell. 1995;80:285–291. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waibel M, Solomon VS, Knight DA, Ralli RA, Kim SK, Banks KM, Vidacs E, Virely C, Sia KC, Bracken LS, Collins-Underwood R, Drenberg C, Ramsey LB, Meyer SC, Takiguchi M, Dickins RA, Levine R, Ghysdael J, Dawson MA, Lock RB, Mullighan CG, Johnstone RW. Combined targeting of JAK2 and Bcl-2/Bcl-xL to cure mutant JAK2-driven malignancies and overcome acquired resistance to JAK2 inhibitors. Cell reports. 2013;5:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiskus W, Verstovsek S, Manshouri T, Rao R, Balusu R, Venkannagari S, Rao NN, Ha K, Smith JE, Hembruff SL, Abhyankar S, McGuirk J, Bhalla KN. Heat shock protein 90 inhibitor is synergistic with JAK2 inhibitor and overcomes resistance to JAK2-TKI in human myeloproliferative neoplasm cells. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:7347–7358. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan I, Huang Z, Wen Q, Stankiewicz MJ, Gilles L, Goldenson B, Schultz R, Diebold L, Gurbuxani S, Finke CM, Lasho TL, Koppikar P, Pardanani A, Stein B, Altman JK, Levine RL, Tefferi A, Crispino JD. AKT is a therapeutic target in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2013;27:1882–1890. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiskus W, Verstovsek S, Manshouri T, Smith JE, Peth K, Abhyankar S, McGuirk J, Bhalla KN. Dual PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitor BEZ235 synergistically enhances the activity of JAK2 inhibitor against cultured and primary human myeloproliferative neoplasm cells. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2013;12:577–588. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gozgit JM, Bebernitz G, Patil P, Ye M, Parmentier J, Wu J, Su N, Wang T, Ioannidis S, Davies A, Huszar D, Zinda M. Effects of the JAK2 inhibitor, AZ960, on Pim/BAD/BCL-xL survival signaling in the human JAK2 V617F cell line SET-2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:32334–32343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Will B, Siddiqi T, Jorda MA, Shimamura T, Luptakova K, Staber PB, Costa DB, Steidl U, Tenen DG, Kobayashi S. Apoptosis induced by JAK2 inhibition is mediated by Bim and enhanced by the BH3 mimetic ABT-737 in JAK2 mutant human erythroid cells. Blood. 2010;115:2901–2909. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarosiek KA, Chi X, Bachman JA, Sims JJ, Montero J, Patel L, Flanagan A, Andrews DW, Sorger P, Letai A. BID preferentially activates BAK while BIM preferentially activates BAX, affecting chemotherapy response. Molecular cell. 2013;51:751–765. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan R, Hogdal LJ, Benito JM, Bucci D, Han L, Borthakur G, Cortes J, Deangelo DJ, Debose L, Mu H, Dohner H, Gaidzik VI, Galinsky I, Golfman LS, Haferlach T, Harutyunyan KG, Hu J, Leverson JD, Marcucci G, Muschen M, Newman R, Park E, Ruvolo PP, Ruvolo V, Ryan J, Schindela S, Zweidler-McKay P, Stone RM, Kantarjian H, Andreeff M, Konopleva M, Letai AG. Selective BCL-2 Inhibition by ABT-199 Causes On-Target Cell Death in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer discovery. 2014;4:362–375. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tse C, Shoemaker AR, Adickes J, Anderson MG, Chen J, Jin S, Johnson EF, Marsh KC, Mitten MJ, Nimmer P, Roberts L, Tahir SK, Xiao Y, Yang X, Zhang H, Fesik S, Rosenberg SH, Elmore SW. ABT-263: a potent and orally bioavailable Bcl-2 family inhibitor. Cancer research. 2008;68:3421–3428. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gandhi L, Camidge DR, Ribeiro de Oliveira M, Bonomi P, Gandara D, Khaira D, Hann CL, McKeegan EM, Litvinovich E, Hemken PM, Dive C, Enschede SH, Nolan C, Chiu YL, Busman T, Xiong H, Krivoshik AP, Humerickhouse R, Shapiro GI, Rudin CM. Phase I study of Navitoclax (ABT-263), a novel Bcl-2 family inhibitor, in patients with small-cell lung cancer and other solid tumors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:909–916. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wood KC, Konieczkowski DJ, Johannessen CM, Boehm JS, Tamayo P, Botvinnik OB, Mesirov JP, Hahn WC, Root DE, Garraway LA, Sabatini DM. MicroSCALE screening reveals genetic modifiers of therapeutic response in melanoma. Science signaling. 2012;5:rs4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Root DE, Hacohen N, Hahn WC, Lander ES, Sabatini DM. Genomescale loss-of-function screening with a lentiviral RNAi library. Nature methods. 2006;3:715–719. doi: 10.1038/nmeth924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang X, Boehm JS, Yang X, Salehi-Ashtiani K, Hao T, Shen Y, Lubonja R, Thomas SR, Alkan O, Bhimdi T, Green TM, Johannessen CM, Silver SJ, Nguyen C, Murray RR, Hieronymus H, Balcha D, Fan C, Lin C, Ghamsari L, Vidal M, Hahn WC, Hill DE, Root DE. A public genome-scale lentiviral expression library of human ORFs. Nature methods. 2011;8:659–661. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnittger S, Bacher U, Kern W, Schroder M, Haferlach T, Schoch C. Report on two novel nucleotide exchanges in the JAK2 pseudokinase domain: D620E and E627E. Leukemia. 2006;20:2195–2197. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakao M, Janssen JW, Seriu T, Bartram CR. Rapid and reliable detection of N-ras mutations in acute lymphoblastic leukemia by melting curve analysis using LightCycler technology. Leukemia. 2000;14:312–315. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kohlmann A, Martinelli G, Hofmann W, Kronnie G, Chiaretti S, Preudhomme C, Tagliafico E, Hernandez J, Gabriel C, Lion T, Vandenberghe P, Polakova KM, Béné M, Brueggemann M, Cazzaniga G, Yeoh A, Lehmann S, Ernst T, Leibundgut EO, Ozbek U, Mills KI, Dugas M, Thiede C, Spinelli O, Foroni L, Jansen JH, Hochhaus A, Haferlach T. The Interlaboratory Robustness of Next-Generation Sequencing (IRON) Study Phase II: Deep-Sequencing Analyses of Hematological Malignancies Performed by an International Network Involving 26 Laboratories. Blood. 2012;120:1399. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.