Abstract

A 6-year-old male India-origin Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) presented with thin body condition and muscular atrophy. Thoracic auscultation revealed a grade VI/VI pansystolic murmur bilaterally. Radiographs showed cardiomegaly with significant left atrial and biventricular enlargement, a dilated pulmonary artery, and hepatomegaly. Electrocardiogram revealed a normal sinus rhythm interspersed with ventricular bigeminy. Hematology showed mild polycythemia and prerenal azotemia. Necropsy demonstrated double-outlet right ventricle with a large subaortic ventricular septal defect, subpulmonary stenosis, small atrial septal defect, and right ventricular hypertrophy. The major histological finding was severe chronic passive hepatic congestion. Double-outlet right ventricle is a rare congenital heart disease, both in human beings and animals.

Keywords: Congenital cardiac defect, double-outlet right ventricle, nonhuman primate, ventricular septal defect

Double-outlet right ventricle (DORV) is a rare form of congenital heart defect, in which both great arteries (aorta and pulmonary trunk) arise from the right ventricle. The defect affects 1–1.5% of patients with congenital heart disease with a frequency of 1 in 10,000 live births in human beings.16 DORV has been described in the veterinary literature in cats,1,9,15,19 foals5,7,21 and calves,17,23,24 with variable clinical and pathologic manifestations. In the current report, the clinical observations, radiographs, electrocardiogram, gross, and histopathologic findings in a Rhesus macaque with a DORV are described.

A 6-year-old male India-origin Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) with no history of illness or trauma presented for project pre-assignment physical examination from the outdoor breeding colony at the Tulane National Primate Research Center (Covington, Louisiana). Upon physical examination, the animal was found to have poor body condition with a body condition score of 1 out of 5. Thoracic auscultation revealed caudal displacement of the heart with a grade VI/VI pansystolic murmur bilaterally. Thoracic radiographs showed a globoid heart with significant enlargement of the left atrium, left auricle, and both ventricles. The aortic shadow was not prominent, but the pulmonary artery trunk was enlarged (Fig. 1). Electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm regularly interspersed with ventricular bigeminy, characterized by tall QRS complexes with deep S-waves at lead II. Hematology showed mild polycythemia and mild prerenal azotemia. All remaining parameters of the complete blood count and serum chemistry were within reference ranges. A body weight of 6.22 kg at the time of presentation was considerably low (mean body weight of 10.24 kg for animals of the same age), and the body weight record showed a consistently poor weight gain since birth. Following 3 months of indoor cage rest, diagnostic testing, and daily observations, the animal had lost 1.22 kg. Stifles were contracted bilaterally with severely reduced range of motion and severe muscle atrophy. Because of deteriorating physical condition, the macaque was humanely euthanized.

Figure 1.

India-origin Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), chest radiograph. The ventrodorsal view shows a generalized cardiomegaly. The prominent bulge (*) indicates main pulmonary artery enlargement. The lower bulge (thick arrow) represents the enlargement of the left auricle. The globoid silhouette of the right heart border indicates right heart enlargement (thin arrow).

Grossly, the animal was severely emaciated and dehydrated with diffuse muscular atrophy. The skin and external mucosa were moderately cyanotic. The heart was markedly enlarged and globoid with severe dilation of the left atrium and auricle and marked enlargement of both ventricles. Externally, the ascending aorta lay nearly parallel, right, and slightly posterior to the dilated and thin-walled pulmonary trunk (Fig. 2). Further examination showed that the aorta originated entirely from the right ventricle. The aortic orifice lay to the right and posterior to the outlet of the normally situated pulmonary trunk. The outflow tracts of the great vessels were separated by the crista supraventricularis. Located in the superior interventricular septum and posterior to the infundibular septum, a 10 mm in diameter ventricular septal defect (VSD) opened at the base of the mitral leaflet and extended beneath the outlet of the aorta in the right ventricle. This interventricular communication was bounded superiorly by the inner ventriculo-infundibular fold and inferiorly by the crest of the muscular septum. With this arrangement of the ventriculo-arterial junctions, the direction of blood flow from the left ventricle appeared to proceed predominantly to the aorta. Below the pulmonary valve, the pulmonary outflow tract was narrowed by a vertical limb of the crista supraventricularis (subpulmonary stenosis). The right ventricle was moderately dilated, and the right ventricular wall was markedly hypertrophied with a thickness of 15 mm (5 mm in a healthy age-matched animal). The left ventricle was mildly hypertrophic with a wall thickness of 15 mm (normally 12 mm; Fig. 3). The papillary muscles in the left ventricle were prominent. The mitral, tricuspid, and semilunar valves were normal, and the coronary arteries were normally distributed. The left atrium was markedly dilated with a thin (2-mm) fibrotic wall. Similar but milder changes were noted in the right atrium. There was a 4-mm irregular hole in the center of the atrial septum (Fig. 4). The liver had diffuse, chronic, passive congestion characterized by severe enlargement with rounded edges of all lobes and an enhanced lobular pattern, especially evidenced on cut surface. The skeletal muscles, especially those of the hind limbs, were severely atrophied.

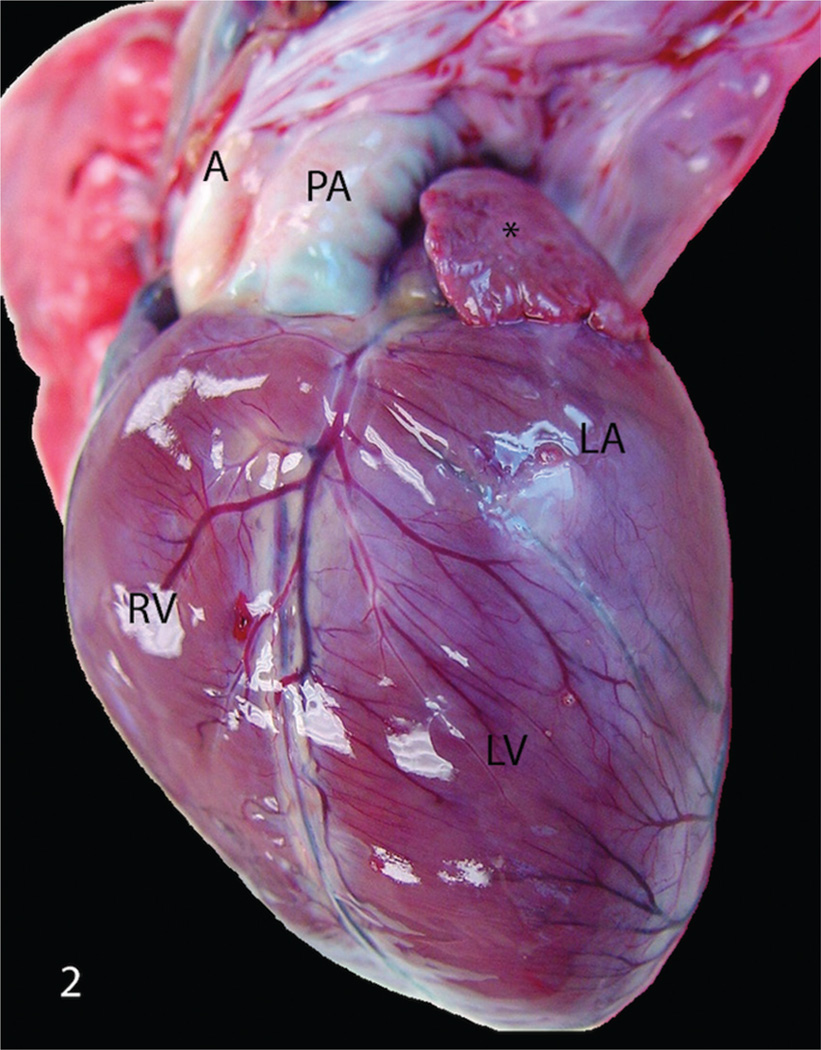

Figure 2.

India-origin Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), heart. Aorta (A) runs parallel to the enlarged pulmonary artery (PA) with the enlargement of the right ventricle (RV), left atrium (LA), and left auricle (*). LV = left ventricle.

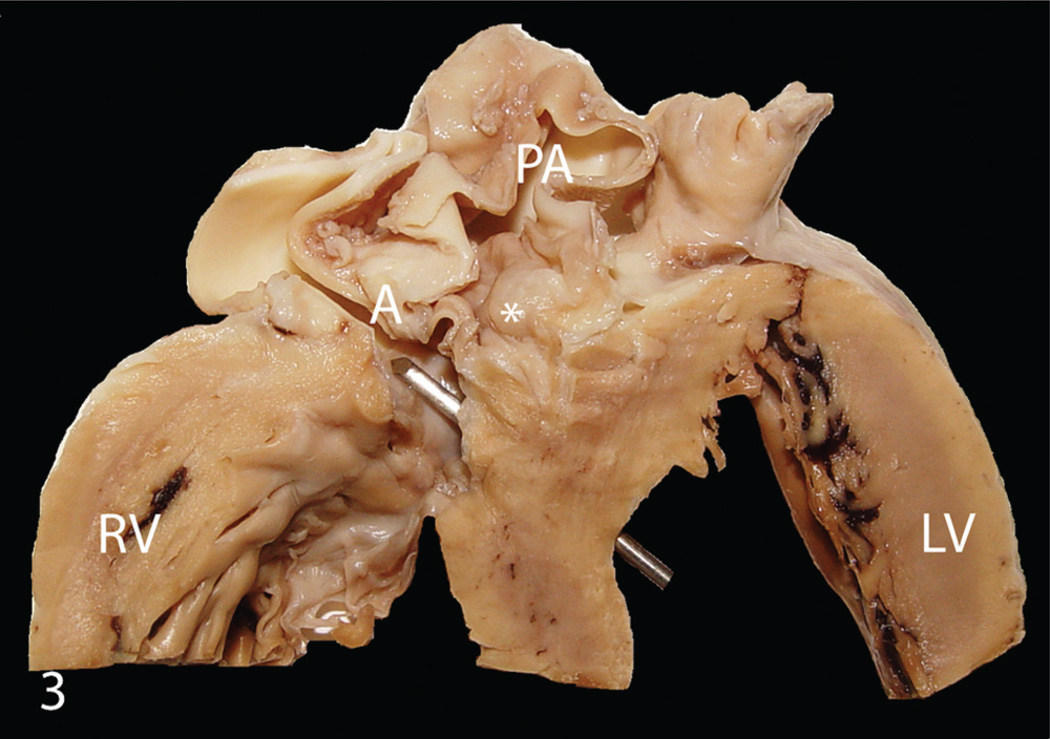

Figure 3.

India-origin Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), cross section of heart. Double-outlet right ventricle characterized by both the aorta (A) and pulmonary artery originating entirely from the right ventricle with a large (10 mm in diameter) subaortic ventricular septal defect (metal bar), subpulmonary stenosis (*), marked hypertrophy of the right ventricular wall (RV), and a severely dilated pulmonary artery (PA). LV = left ventricle.

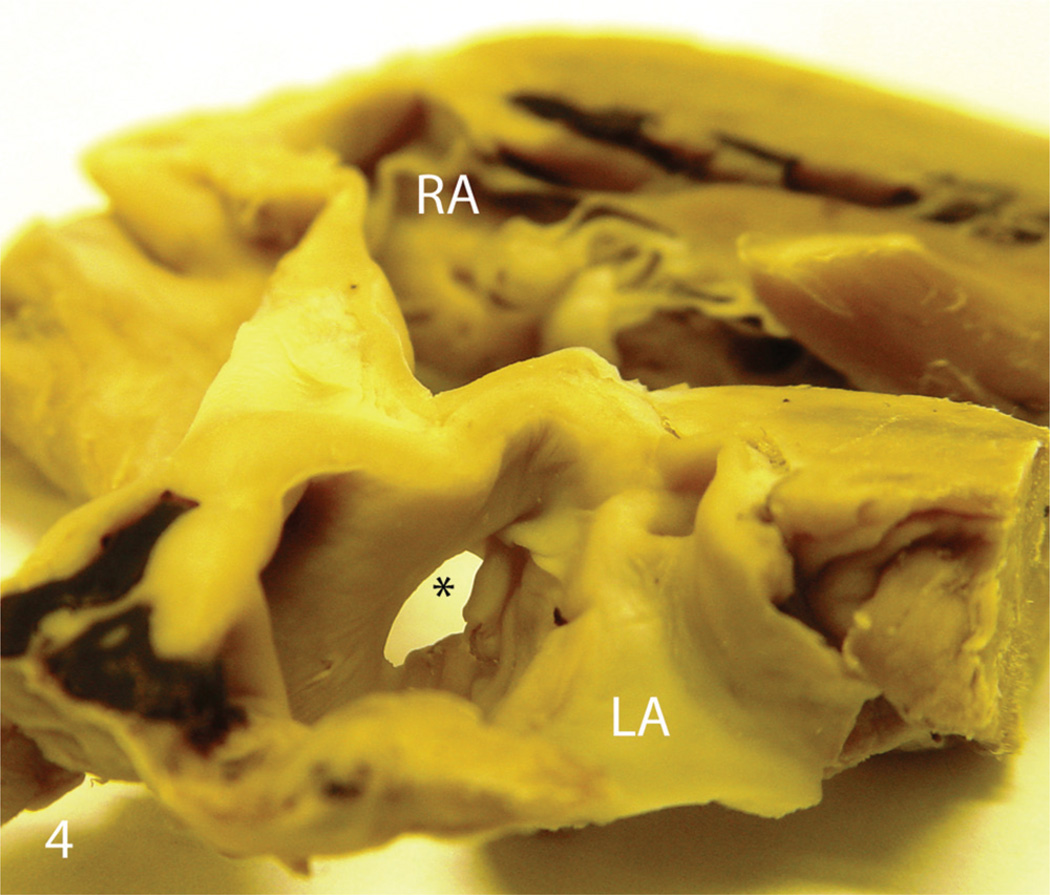

Figure 4.

India-origin Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), cross section of heart. There is a small (4 mm in diameter) atrial septal defect (*) at the center of atrial septum. LA = left atrium; RA = right atrium.

Histopathologically, the right ventricular free wall was approximately 4 times thicker than normal. Diffusely, cardiomyocytes were markedly hypertrophic and enlarged 2–3 times more than normal with abundant eosinophilic fibrillar sarcoplasm and a large vesicular central nucleus. Multifocally, there was myocardial necrosis characterized by eosinophilic sarcoplasma and pyknotic nuclei. The fibrosis was minimal, and an increased amount of connective tissue surrounded the vessels. Similar but milder changes were present in the left ventricle, papillary muscle, and interventricular septum. In the liver, there was severe, diffuse hepatic congestion with marked engorgement of central veins, which were surrounded by an increased amount of connective tissue. The hepatocytes were moderately to severely atrophic, and hepatic cords were tortuous, disorganized, and compressed by markedly dilated sinusoids. These changes were especially severe near the central veins. Mild chronic fibrosis was present in the hepatic capsule and most portal areas, and was accompanied by mild biliary hyperplasia and a small number of infiltrates of mononuclear leukocytes. The lungs presented with mild pulmonary congestion and edema. The vessels were moderately dilated and surrounded by an increased amount of fibrotic tissue. The alveolar septae were mildly thickened by fibrous tissue.

DORV comprises a group of cardiac anomalies in which both the aorta and pulmonary trunk originate predominantly or entirely from the right ventricle.14 A ventricular septal defect is almost invariably present and serves to eject blood from the blind left ventricle into the right ventricle since the left ventricle has no direct communication to either great artery. Currently in human medicine, DORV is classified into 4 distinct groups according to the relationship between the VSD and blood vessels: DORV with subaortic VSD, DORV with subpulmonary VSD (Taussig Bing malformation), DORV with doubly committed VSD, and DORV with noncommitted VSD.16,22 The most frequent anatomic type is the subaortic VSD, which is further divided into the Fallot type if pulmonary stenosis is present or the Eisenmenger anomaly if pulmonary stenosis is absent.3,6 Approximately 50% of patients with DORV have pulmonary stenosis. The resulting physiology is similar to tetralogy of Fallot, in which systolic pressures are equal in both ventricles and in the aorta.18 On physical examination, patients usually have a prominent right ventricular impulse, systolic thrill at the left upper sternal border, a harsh systolic murmur, and a single second heart sound.2

The case described herein is similar to the Fallot type of DORV in human beings. Clinically, DORV with subaortic VSD and pulmonary stenosis is indistinguishable from classic tetralogy of Fallot.6 With subaortic VSD, the left ventricular outflow is directed toward the aorta, resulting in aortic oxygen saturation that exceeds pulmonary saturation. Due to a combination of turbulent flow and aberrant pulmonary pressure, the pulmonary trunk becomes dilated and thin walled. Because of the increased blood pressure from the left ventricle by the VSD, concentric right ventricular hypertrophy is always present.13 In the present case, mild polycythemia and prerenal azotemia were likely due to dehydration and chronic passive hepatic congestion. Electrocardiogram revealed a normal sinus rhythm interspersed by ventricular bigeminy, but electrocardiogram has low predictive value for the diagnosis of DORV.12

In human beings, the incidence of cardiovascular malformations is 0.8% of live births, and 4.5% of them are DORV.16 In horses, 0.5% of equine necropsy specimens have cardiovascular malformations. Of these, 12.5% have DORV, suggesting that it is a more common malformation in horses.7 DORV is rarely documented in other animals. Interestingly, the macaque in the present study also had an atrial septal defect. Atrial septal shunt was reported in 5 DORV patients with a high left atrial pressure associated with a true atrial septal defect as opposed to a dilated foramen ovale.20

Like many other conotruncal heart defects, DORV is probably of neural crest origin.11 The cardiac septum is derived from the neural crest, and removal of the neural crest during development results in outflow tract malformations. Malformations such as DORV, tetralogy of Fallot, and Eisenmenger complex are common if smaller portions of the cardiac neural crest are deleted. A chromosome band 22q11 deletion has been confirmed to be associated with congenital heart diseases.8,10 Approximately 5% of patients with DORV have this deletion.4 The assay for 22q11 deletion was not performed in the current case. In summary, the clinical signs, radiographic findings, and postmortem and histopathological examination reported herein of a Rhesus macaque showed a rare congenital heart defect characterized by DORV, large ventricular septal defect, subpulmonary stenosis, and a small atrial septal defect.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the technicians and animal care staff at Tulane National Primate Research Center, and Dr. Drew Baldwin at Tulane Heart & Vascular Institute for the interpretation of electrocardiogram.

Funding

This work was supported by Tulane National Primate Research Center base grant P51 RR000164 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Abduch MC, Tonini PL, de Oliveira Domingos Barbusci L, et al. Double-outlet right ventricle associated with discordant atrioventricular connection and dextrocardia in a cat. J Small Anim Pract. 2003;44:374–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2003.tb00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson RN, McCarthy K, Cook AC. Double outlet right ventricle. Cardiol Young. 2001;11:329–344. doi: 10.1017/s1047951101000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartelings MM, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Morphogenetic considerations on congenital malformations of the outflow tract. Part 2: complete transposition of the great arteries and double outlet right ventricle. Intl J Cardiol. 1991;33:5–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(91)90147-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belli E, Serraf A, Lacour-Gayet F, et al. Double-outlet right ventricle with non-committed ventricular septal defect. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:747–752. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaffin MK, Miller MW, Morris EL. Double outlet right ventricle and other associated congenital cardiac anomalies in an American miniature horse foal. Equine Vet J. 1992;24:402–406. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1992.tb02865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards WD. Double-outlet right ventricle and tetralogy of Fallot. Two distinct but not mutually exclusive entities. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1981;82:418–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fennell L, Church S, Tyrell D, et al. Double-outlet right ventricle in a 10-month-old Friesian filly. Aust Vet J. 2009;87:204–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2009.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldmuntz E, Clark BJ, Mitchell LE, et al. Frequency of 22q11 deletions in patients with conotruncal defects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:492–498. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeraj K, Ogburn PN, Jessen CA, et al. Double outlet right ventricle in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1978;173:1356–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khositseth A, Tocharoentanaphol C, Khowsathit P, Ruangdaraganon N. Chromosome 22q11 deletions in patients with conotruncal heart defects. Pediatr Cardiol. 2005;26:570–573. doi: 10.1007/s00246-004-0775-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirby ML, Waldo KL. Role of neural crest in congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1990;82:332–340. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krongrad E, Ritrer DG, Weidman WH, DuShane JW. Hemodynamic and anatomic correlation of electrocardiogram in double-outlet right ventricle. Circulation. 1972;46:995–1004. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.46.5.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maxie MG, Robinson WF. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s pathology of domestic animals. 4th ed. Vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007. Cardiovascular system; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neufeld HN, DuShane JW, Edwards JE. Origin of both great vessels from the right ventricle. II. With pulmonary stenosis. Circulation. 1961;23:630–612. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.23.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Northway RB. Use of an aortic homograft for surgical correction of a double-outlet right ventricle in a kitten. Vet Med Small Anim Clin. 1979;74:191–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peixoto LB, Leal SM, Silva CE, et al. Double outlet right ventricle with anterior and left-sided aorta and subpulmonary ventricular septal defect. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1999;73:441–450. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x1999001100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prosek R, Oyama MA, Church WM, et al. Double-outlet right ventricle in an Angus calf. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19:262–267. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2005)19<262:drviaa>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sondheimer HM, Freedom RM, Olley PM. Double outlet right ventricle: clinical spectrum and prognosis. Am J Cardiol. 1977;39:709–714. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(77)80133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Linde-Sipman JS, van den Ingh TS, Koeman JP. Congenital heart abnormalities in the cat. A description of sixteen cases. Zentralbl Veterinarmed A. 1973;20:419–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.1973.tb00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venables AW, Campbell PE. Double outlet right ventricle. A review of 16 cases with 10 necropsy specimens. Br Heart J. 1966;28:461–471. doi: 10.1136/hrt.28.4.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vitums A. Origin of the aorta and pulmonary trunk from the right ventricle in a horse. Pathol Vet. 1970;7:482–491. doi: 10.1177/030098587000700602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walters HL, 3rd, Mavroudis C, Tchervenkov CI, et al. Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project: double outlet right ventricle. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:S249–S263. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson RB, Cave JS, Horn JB, Kasselberg AG. Double outlet right ventricle in a calf. Can J Comp Med. 1985;49:115–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zulauf M, Tschudi P, Meylan M. [Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) in a 15 month old heifer] Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2001;143:149–154. In German. Abstract in English. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]