Abstract

Recombinant spider silks produced in transgenic goat milk were studied as cell culture matrices for neuronal growth. Major ampullate spidroin 1 (MaSp1) supported neuronal growth, axon extension and network connectivity, with cell morphology comparable to the gold standard poly-lysine. In addition, neurons growing on MaSp1 films had increased neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) expression at both mRNA and protein levels. The results indicate that MaSp1 films present useful surface charge and substrate stiffness to support the growth of primary rat cortical neurons. Moreover, a putative neuron-specific surface binding sequence GRGGL within MaSp1 may contribute to the biological regulation of neuron growth. These findings indicate that MaSp1 could regulate neuron growth through its physical and biological features. This dual regulation mode of MaSp1 could provide an alternative strategy for generating functional silk materials for neural tissue engineering.

Keywords: Biomaterial, Neural cell, Silk, Recombinant protein, Tissue engineering

INTRODUCTION

Central nervous system regeneration remains one of the most challenging tasks in regenerative medicine. Neural engineering strategies have been explored for aiding nerve regeneration, including implanted artificial extracellular matrixes to support neural cell grafts[1, 2], nerve guidance conduits for promoting glial cell migration and axon outgrowth[3] and controlled delivery systems for growth factors and suppressing inhibitory scar formation[4]. These approaches provide control of the microenvironment of neural cells by presenting biophysical, topographical and biochemical cues to assist neuronal adhesion, extension and connectivity. To support these applications, it is necessary to have suitable biomaterials that promote optimal neuronal growth. Accordingly, a variety of biocompatible materials have been explored in primary neuronal cultures, including extracellular matrix proteins[5] and synthetic polymers[6]. However, there are limited options for neural-compatible materials due to the insufficient understanding of neuron-material interactions.

It is well-known that the physical properties of the matrix play an important role in neuronal growth. Extensive studies have shown that substrate stiffness can modulate axon outgrowth, as neuronal cells display a preference to a particular range of mechanical stiffness[7-10]. This effect is thought to interact with the contractile forces generated by the cytoskeletal components such as the microtubule and actin filaments of the axon during different stages of axonal outgrowth, including extension, retraction and elongation[8, 11]. In addition, positive surface charge is necessary for neuronal surface adhesion to the substrate[12]. Surface coatings with positively charged poly-peptides such as poly-lysine are routinely used to facilitate neuronal adhesion to synthetic materials.

Specific cell-interacting motifs are necessary for cells to sense the surroundings and convert the information to modulate cellular behavior. Neurons have neural specific cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), such as NCAM, that are involved in mediating neuronal cell-cell adhesion[13]. As one of the first adhesion molecules extensively characterized[14]. NCAM has been shown to mediate cell-cell binding by homophilic interactions[15] as well as interacting with a variety of other cellular proteins such as receptors[16], membrane-cytoskeletal components[17] and the cellular prion protein (PrP)[18]. NCAM-mediated cell adhesion is found to be a critical step for triggering signaling events that lead to neurite outgrowth[19].

Considering these various needs for neuronal growth, a useful biomaterial for neural engineering should provide suitable surface binding cues as well as appropriate physical properties. Traditional cell culture matrices include chemically synthesized polymers (e.g. poly-lysine, poly-ethylene glycol, poly-lactic acid) as well as naturally extracted extracellular matrix proteins from mammalian organs and tissues (e.g. collagen, fibronectin, laminin, Matrigel™). While synthetic polymers may possess higher versatility in material fabrication for specific needs, they usually lack biologically active sites to communicate with cells and assist their growth, and thus do not mimic the in vivo environment very well. On the other hand, naturally extracted extracellular matrix proteins are usually bioactive and have positive influences on cell growth. However, they suffer from batch-to-batch variations and generally have more undefined components due to the lack of standardized extraction protocols[20, 21]. There is a need for new sources of matrices for tissue engineering that could overcome both the limitations of synthetic and naturally extracted materials. Recently, the excellent material properties of silk proteins originated from silkworms and spiders, have drawn increased attention from tissue engineers to investigate their potential as biomaterials for tissue regeneration[22, 23].

Silk fibroins are attractive biomaterials due to their tunable mechanical properties and biocompatibility. Using silkworm (Bombyx mori) silk-based biomaterials, we have previously identified the optimal ranges of physical properties, such as surface charge and mechanical stiffness, to support the growth of primary rat cortical neurons[9, 10]. Recombinant silk-elastin proteins have also been shown to support neuronal growth when combined in appropriate ratios[12]. Furthermore, spider silk has been used to repair nerve defects[24] and a recombinant spider silk mimic supported the growth of neuron stem cells in both 2D and 3D cultures[22].

Spider silks represent a unique group of fibrous proteins that contain multiple basic protein motifs which control various structural and functional aspects of the protein. Typical orb-weaving spider produces seven types of silks[25]. Among them, dragline silk, the lifeline of spider, displays the most extraordinary mechanical properties with both high tensile strength and elasticity, it is known as one of the toughest materials by weight in the world. Despite being an ancient material, the molecular nature of dragline silk has only started to be unraveled over the last two decades[25, 26]. Previous studies have identified that dragline silk is comprised by two proteins: major ampullate spidroin 1 (MaSp1) and major ampullate spidroin 2 (MaSp2)[27, 28]. MaSp1 contains two distinct motifs: a poly-alanine region that forms tightly packed beta-sheet crystalline that contribute to the tensile strength of dragline silk; a GGX motif (X=L, Y, Q, A), which forms glycine II helix to connects crystalline regions in an amorphous matrix and may provide elasticity. MaSp2 also contains poly-alanine regions, but is distinct from MaSp1 due to a GPGXX motif (X= G, Q, Y) which forms beta-spirals and is responsible for dragline silk's high elasticity[29]. In the native spider silk sequence, these motifs were repeated hundreds of times to form proteins with molecular sizes of more than 300kDa[25]. Besides the main repetitive sequences, spider silk also contains a highly conserved terminal domain[30, 31] which likely plays a role in protein aggregation and fiber formation[32] and to control protein solubility when the secreted protein is stored in the silk gland at high concentrations[33].

In order to investigate the mechanisms behind the interaction between neuron cells and the silk matrices, and potentially expand the candidates pool of silk matrices for neuron culture, recombinant MaSp1 and MaSp2 proteins based on Nephila clavipes dragline silks were produced in this study. The two silk proteins were studied for their ability to support the growth of rat cortical neurons in comparison to poly-L-lysine as well as to B. mori silk coatings that have been routinely used in our lab for neuronal growth.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant spider silk protein expression and purification

MaSp 1 and MaSp2 were purified and analyzed according to published procedures by Tucker, et al.[34]. Briefly, goat milk was collected and defatted before pumping through a tangential flow filtration system with 750KDa and 50KDa membrane to obtain clarified and concentrated solution with recombinant spider silks. The spider silk proteins were precipitated by ammonium sulfate from remaining milk proteins, washed with dH2O and lyophilized. Protein purity was tested by Western blots using M5 as primary antibody and AP conjugated anti-rabbit antibody as secondary antibody.

Regenerated silkworm silk preparation

The procedure to prepare lyophilized silkworm silk from B. mori cocoons was previously described[35]. Briefly, cocoons were degummed by boiling 60 min in Na2CO3 solution (20 mM) to remove sericin. Silk fibroin was dissolved in LiBr solution (9.3 M) at 60°C for a final concentration of 20 wt%. This solution was dialyzed against water using Slide-a-Lyzer dialysis cassettes (Pierce, MWCO 3,500) for 72 h. The aqueous silk solution was lyophilized to obtain dried silk fibroin.

Peptide synthesis

Peptide (GRGGLAAAGRGGLAAAGRGGLGY) carrying the putative NCAM binding sequence GRGGL was synthesized by FMOC chemistry at the Tufts core facility. Half of the peptide was labeled by FITC-AHA (fluorescein-5-aminohexylacrylamide) at the N-terminus for neuron surface coatings. All peptides were purified to 95% pure by HPLC and molecular weight confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Silk film preparation

Lyophilized silks (MaSp1, MaSp2 and silkworm silk) were dissolved in 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) to prepare a 2 wt% solution, For cell culture, 150 ul of solution were applied to each well in 24-well tissue culture plates and dried completely in a laminar flow hood. For dynamic mechanical analysis, silk films were cast on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) molds instead of tissue culture plastic for easy peeling. Silk films were annealed by submerging the samples in 90% methanol for 30 min and washing with ethanol followed by Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) three times and the allowed to dry completely.

Primary cortical neuronal culture

Primary cortical neurons from embryonic day 18 (E18) Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA) were plated on 24-well plates with different silk substrates described previously. The brain tissue isolation protocol was approved by Tufts University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and complies with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (IACUC # B2011-45). Control wells were coated with 1 mg/mL poly-L-lysine (Mr=75,000-150,000D, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to Sigma's procedure. For synthetic GRGGL peptide coatings, the peptide solution with varied concentrations were added to each well and incubated in room temperature overnight. The solution was removed by aspiration and plates were thoroughly rinsed by DPBS before cell seeding. Cells were plated at a density of 250,000 cells per well (125,000 cells/cm2) and cultured in NeuroBasal media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with B-27 neural supplement, penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml and 100 μg/ml), and GlutaMax™ (2 mM) (Invitrogen). Cells were cultured in an incubator (Forma Scientific, Marietta, OH, USA) with 37°C, 100% humidity and 5% CO2 for up to 7 days in vitro (DIV).

Cell viability assay and image analysis

Cell viability was assessed using the LIVE/DEAD Viability Assay Kit (Invitrogen). Briefly, culture media was replaced with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; Invitrogen) containing calcein AM (4 μM) and ethidium homodimer-1 (2 μM). After a 30 minute incubation at 37°C, the cells were changed into fresh culture media, and viewed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DM IL; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a digital camera (Leica DFC340 FX).

Fluorescence images were acquired using excitation at 470±20 nm and emission at 525 ±25 nm for live cells, and excitation at 560±20 nm and emission at 645 ±40 nm for dead cells, respectively. Images were analyzed using NIH ImageJ software. Thresholds for positive live staining and positive dead staining were selected for each image. Particles of positive staining with sizes in-between 10-50 μm were counted as individual cells.

To quantify neuronal growth, a custom-made Image J plugin based on NeurphologyJ[36] was used. Cell soma and neurites were separately identified based on their different intensity thresholds, and simultaneously measured for their numbers and morphological features.

Synthetic peptide cell-binding assays

Peptide (GRGGLAAAGRGGLAAAGRGGLGYC) was tested as either coatings on tissue culture plastic or by direct neuron surface labeling when conjugated with FITC. For plate coating, 1 mL aqueous solution of 10, 100, 1000 μg/mL peptides were applied to each well in 24-well tissue culture plates and dried completely in a laminar flow hood. Neurons were seeded and cultured for 4 days. At DIV3, cultures were subjected to cell viability assay. For cell surface binding, DIV5 neurons grown on Poly-L-lysine coated tissue culture plate (TCP-pll) surfaces were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed, and incubated with FITC-tagged peptides (10, 100, 1000 μg/mL) overnight. After three 10 min washes, cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (1 g/mL, Sigma), and subjected to fluorescence microscopy. For inhibition studies, cells were incubated with the peptides (10, 100, 500 μg/mL) for 30 min prior to seeding. Cell/peptide mixture was plated on MaSp1 films and cultured for 3 days. At 3hr post seeding, cultures were subjected to phase-contrast microscopy.

NCAM solid state binding assay

The affinity of NCAM to different substrates was evaluated using solid state binding assay. Different types of silk films and poly-lysine were coated onto Immulon 2 HB 96-well assay plates (Thermo Scientific) with method mentioned above but scaled down according to the surface areas. Plates were blocked by 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hr at RT. Recombinant NCAM (R&D Cat#2408-NC-050) was subsequently added to each well at a concentration of 10 μg/ml and incubated for 1 hrs. Bound NCAM on silk films were detected by mouse anti-human NCAM antibody (1:500, R&D) for 1 hr. Secondary anti-mouse HRP antibody (1:3000, Santa Cruz) was incubated for 1 hr and 50 μl of TMB (3,30,5,50-tetramethylbenzidine) solution (Invitrogen) was added for the colorimetric reaction. Plates were washed by 150 μl of PBST for 6 times between every step. Color was allowed to develop at room temperature for 10 min and 50 μl of 1 N HCl was added to stop the reaction. OD450nm was recorded from the 96-well plate using a Spectra Max M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) for data analysis. Appropriate controls included NCAM directly coated onto plates (+) and uncoated plates blocked by BSA (−). All assays were performed in triplicates.

mRNA expression analysis

After 12-days of culture on the different matrices, total RNA from the neurons was extracted using an RNAesy Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and quantified by UV absorbance at 260 nm. Aliquots of 5μg of RNA were treated with DNAase I (Sigma), and then reverse transcribed to cDNA using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad). The level of NCAM mRNA expression was determined by real-time qPCR using Brilliant QPCR Master Mix (Agilent) and Rat Ncam1 TaqMan Probe and primers (cat#Rn00580526_m1, Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The final results were normalized with GAPDH (cat#Rn01775763_g1, Applied Biosystems) expression levels.

NCAM expression analysis

Total protein from neuron cell culture was isolated by standard RIPA buffer extraction (Pierce) after 12-days of culture. Protein concentration was determined by BCA assay (Pierce) before Western blotting following the manufacturer's instruction. Samples were denatured in NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer 4X (Invitrogen) at 98°C. Then 15 μg of protein was run on 4-12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) at 150 V for 1.5 hr following membrane transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) at 30 V for 1 hr. Membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBST for 2 hrs prior to incubation with mouse polyclonal antibodies directed against NCAM (1:500, R&D) or β-actin (1:1000, R&D) for 48-72 hrs at 4°C. Anti-mouse IgG (H+L) HRP secondary antibody (was applied for 60 minutes at room temperature (1:3000) prior to washing with PBST. Membranes were visualized by Novex® ECL Chemiluminescent Substrate Reagent Kit (Invitrogen). Blots were subsequently imaged on Syngene G:BOX system.

Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA)

Free-standing MaSp1 and MaSp2 films were trimmed into rectangular shape (25 mm length, 7 mm width). Films were pre-hydrated in neuron basal medium for 1 h to reach a swelling equilibrium prior to testing. Thickness of the films was measured by micrometer and found to be 62μm ± 7.5μm. The studies were performed on a TA Instruments RSA3 dynamic mechanical analyzer with RSA-G2 immersion system. Test samples were submerged in neuron basal medium in an RSA-G2 solvent cup during DMA measurements. The frequency/temperature sweep tests at a strain of 0.1%, with 3 different frequencies, 0.1, 1.0, and 10 Hz, were performed from 23°C to 40°C with an increase of 1°C per step and a soak time of 45 s per step. The storage modulus, E', which is related to the elastic deformation[37], and the loss modulus, E”, which is related to the viscous deformation and energy absorption[37] were measured.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative analyses were performed at least in triplicate, and the mean values obtained. Results presented were based on the averages of data points and standard error of mean as error bars. The significance level was determined by p-value using two sample paired student's t-test between the means of two samples, p<0.05 is considered statistically significant. Figures were plotted in Microcal Origin 6.0 or Microsoft Excel 2010.

Results

Recombinant protein production and purification

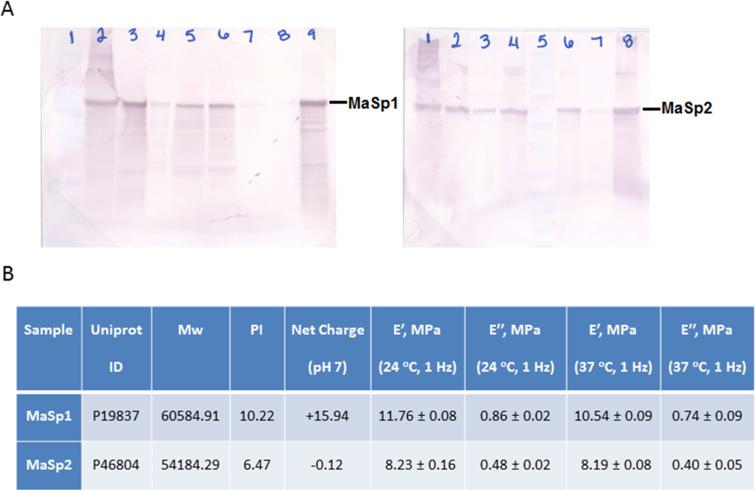

The purified protein recovery was 1g/L for MaSp1 and 0.2g/L for MaSp2. Recombinant spider silk proteins after successive washes have been analyzed by western blots (Figure 1A), last lane of each blot shows the final product. Small amount of degradation were detect but the final products are better than 90% pure particularly since the spider silk proteins stain poorly with protein stains.

Figure 1.

Recombinant protein purification and characterization. (A) Western blot analysis of recombinant MaSp1 (left) and MaSp2 (right) preparations. Final products are shown in lane 9 (left) and lane 8 (right) respectively. Lane 1 (left) and lane 5 (right) are the protein standard. All other lanes show successive washes steps of the sample after ammonium sulfate precipitation. (B) A summarized table shows MaSp1 and MaSp2 sequence, calculated molecular weights and isoelectric points, net charges at physiology condition and the storage and loss modulus measured by DMA.

MaSp1 supports cortical neuron growth

Live imaging was used to examine primary rat cortical neuronal growth on silk films (Figure 2). Cultures grow on TCP-pll were used as positive controls. Similar to our previous findings[12], cortical neurons did not attach to un-coated B. mori silk films. In contrast, neurons attached to MaSp1 films by 24 hr and showed robust neurite outgrowth by 3 days in vitro (DIV3), and formed extensive networks by DIV7. The growth on MaSp1 was almost indistinguishable from that on TCP-pll, except that the neuronal clusters were slightly larger indicating greater aggregation of neurons. Interestingly, neurons did not grow on MaSp2 films.

Figure 2.

Primary rat cortical neuron growth on silk films. (A) Representative fluorescence live images of primary rat cortical neurons (live cells in green, dead cells in red) growing on different substrates: poly-L-lysine coated tissue culture plate (TCP-pll), b. mori silk film, MaSp1 film, and MaSp2 film. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Image processing of neuronal networks. For a representative fluorescence image of neuronal culture (m), this method first identifies cell soma and neurite based on their different intensity thresholds from the background (n), followed with segmentation and nucleus removal procedures that outline the morphological features (o). Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Quantification of neuronal growth: (p) Live cell percentage (live cell count/total cell count). (q) Axon length.

To quantify neuronal growth, we adapted the NeurophysiologyJ program[36] in order to batch process complex neural networks (Fig. 2B). In this method, cell soma and neurites were separately identified based on their different intensity thresholds, and simultaneously measured for their numbers and morphological features. Live cell percentage (live cell count/total cell count, Fig. 2C-p) showed that neurons had similar initial attachment on TCP-pll and MaSp1, yet more viable cells at DIV3 on MaSp1 compared to the positive control (TCP-pll). Axon length quantification (Fig. 2C-q) showed that though the neurites on MaSp1 were significantly shorter than on TCP-pll at 24hr, they eventually grew to similar lengths by DIV3.

Physical properties of MaSp1 contribute to improved neuronal growth

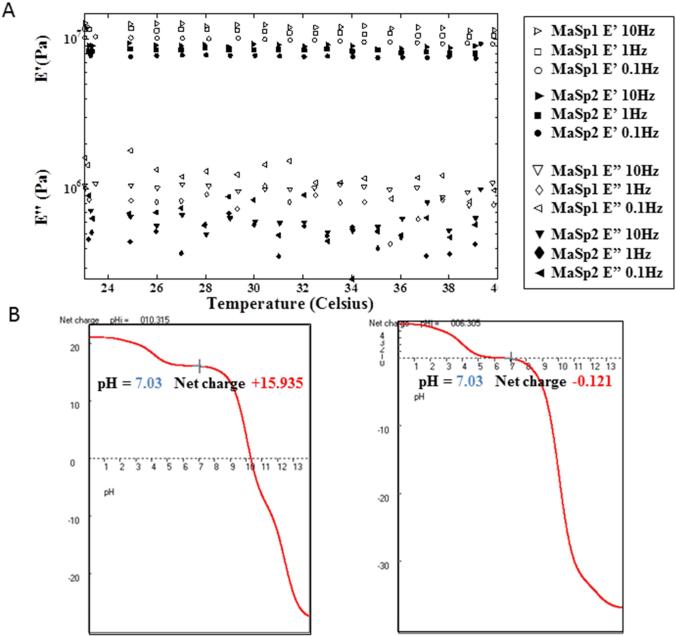

Previous studies have reported that many physical properties of matrices affect neuronal growth, requiring optimal substrate stiffness[7] and positive charge[12], MaSp1 is believed to be stiffer than MaSp2, due to the higher poly-alanine crystalline content and the presence of a unique GPGXX elastic module in the MaSp2 sequence[29, 38]. To investigate whether the fabricated recombinant MaSp1 film was stiffer than MaSp2 films, dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) of the films was carried out in NeuroBasal media to best mimic the growth environment of neurons (Figure 3A). At physiological temperatures, MaSp1 had a higher storage modulus (10.54 ± 0.09 MPa versus 8.19 ± 0.08 MPa) as well as a higher loss modulus (0.74 ± 0.09 MPa versus 0.40 ± 0.05 MPa) compared to MaSp2 films, indicating greater elasticity and viscosity, respectively. A temperature change from 23°C to 40°C did not affect the stiffness significantly.

Figure 3.

MaSp 1 and MaSp2 films viscoelastic profile and charge calculation. (A) Dynamic mechanical analysis of MaSp1 and MaSp2 films in neuron basal medium (B) Net charge of MaSp1 and MaSp2 under various pH.

Sequence analysis of MaSp1 and MaSp2 determined that MaSp1 had a higher isoelectric point (pI) than MaSp2 (10.22 versus 6.47). The net charge of MaSp1 and MaSp2 at various pHs was calculated in ANTHEPROT server (http://antheprot-pbil.ibcp.fr) to evaluate potential charge effects on neurons. Based on the calculations (Figure 3B), at pH7 MaSp1 is positively charged (+15.94), while MaSp2 is close to 0. Interestingly, a silk-elastin chimeric protein SE75 (75% w/w silk fibroin blended with 25% tropoelastin) previously characterized in our lab that supported neuron cell growth also carried a similar charge (+15.6) at pH7[12].

The MaSp1 and MaSp2 sequences as well as their physical characterization data were summarized in Figure 1B. Both stiffness and net charge analysis showed that MaSp1 had suitable physical properties for neuronal growth. This may partially explain our observation that cortical neurons grew better on MaSp1 compared to MaSp2.

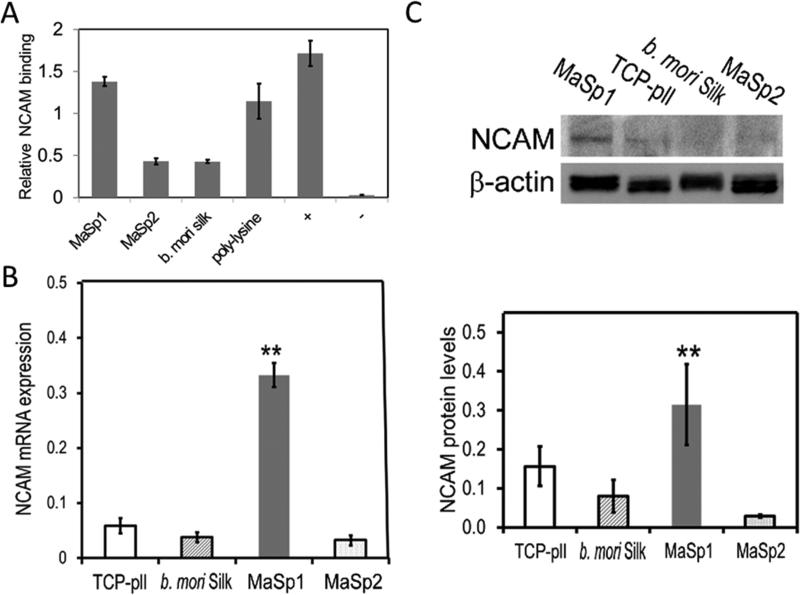

NCAM has higher affinity to MaSp1 film in solid state binding assay

Due to its role in regulating neuronal adhesion and interactions, the affinity level of neuronal cell adhesion molecules (NCAM) to different types of silk surfaces were measured using solid binding assay (Figure 4A). Human recombinant NCAM were used due to the unavailability of commercial rat NCAM. Human and rat NCAM sequence shared 95.2% of similarity based on alignment of human and rat NCAM sequence in UniProt database (www.uniprot.org, entry ID P13591 for Homo sapiens and P13596 for Rattus norvegicus). The binding assay showed that the amount of NCAM bound to MaSp1 film was comparable to the positive controls which coated NCAM directly onto the assay plate. MaSp2 and b. mori silk showed significant less binding which was only 1/3 compared to MaSp1, while poly-L-lysine coating also had good affinity to NCAM similar to MaSp1 film. Results from this binding assay suggested that MaSp1 has improved binding to NCAM.

Figure 4.

Affinity of NCAM on different substrates, mRNA and protein expressions of neurons cultured on silk films (A) Solid state binding of human recombinant NCAM on silk films. (B) Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) of NCAM mRNA levels of neurons at DIV12. (C) Western blot of NCAM protein: (upper) representative blot; (bottom) quantification of protein levels, expressed as NCAM blot density normalized again β-actin blot density.

NCAM expression was upregulated in neurons cultured on MaSp1 film

The mRNA and protein levels of NCAM in neuronal cultures on different substrates were evaluated by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and Western blot. Neurons grown on MaSp1 showed more than a 4-fold higher NCAM mRNA expression level than on TCP-pll (0.27 ±0.08 vs 0.06±0.01; Student's t-test, **, p<0.01; n =5 and 3, respectively) (Figure 4B). In comparison, NCAM mRNA expression was significantly lower of neurons grown on B. mori silk or MaSp2 (0.04± 0.01 vs. 0.03± 0.01, n=3 and 3, respectively).

In addition, Western blots showed that neurons grown on MaSp1 had a NCAM protein level almost 2-fold that on TCP-pll (0.31 ±0.10 vs 0.16±0.05; Student's t-test, **, p<0.01; n =5 and 3, respectively) (Figure 4C). In comparison, NCAM protein levels were significantly lower for neurons grown on B mori silk or MaSp2 (0.08± 0.04 vs. 0.03± 0.003, n=3 and 2, respectively).

A putative peptide sequence that interacts with neuronal surface

The cell morphology differences accompanied by the change in NCAM expression between MaSp1 and MaSp2 led us to hypothesize that there might be other factors besides physical properties that regulate neuronal growth, for example, amino acid sequence that could bind to cell surface receptors and mediate cell signaling. Scanning of MaSp1 and MaSp2 sequences identified no known amino acid sequences that have been previously characterized to enhance cell adhesion, such as RGD[39] or GFPGER[40]. Sequences previously reported to specifically bind NCAM were also not found[15]. MaSp1 and MaSp2 primary sequences bear some similarities, such us poly-alanine motifs and a homologous C-terminus. The most significant sequence difference is between the GGX motif in MaSp1 and the GPGXX motif in MaSp2. Sequence alignment analysis was used to identify peptide sequences that had homology with known brain ECM proteins and neuron-neuron adhesion proteins. A total of 32 proteins were aligned with MaSp1 sequences by ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) using standard settings. A short sequence GRGGL was found to share homology with brain aggrecan core protein[41]. MaSp1 has eight repeats of GRGGL, while MaSp2 has none.

Peptide (GRGGLAAAGRGGLAAAGRGGLGYC) was synthesized in order to investigate the possibility that the GRGGL sequence interacted with neurons. To reach sufficient length for effective cell culture coatings, three GRGGL repeats were linked by three alanine residues and a cysteine residue was included for disulfide coupling. A tyrosine residue is also added at the C-terminus for concentration determination by UV absorbance at 280nm. Peptides were tested as either coatings on tissue culture plastic or by direct neuron surface labeling when conjugated with FITC. Neurons were grown on TCP surfaces that were coated with different concentrations of GRGGL peptides (10, 100, 1000 μg/mL; Figure 5A). Live cell staining showed robust neuronal growth on peptide-coated surfaces, and the growth was proportional to the peptide concentration on the surface. Indeed, neurite length measurements at DIV3 showed that the highest concentration of peptide coating (1,000 μg/mL) had the longest neurites compared to lower concentrations of peptide in the coatings. Conversely, FITC-tagged GRGGL peptides were applied to neurons grown on TCP-pll surfaces at different concentrations (10, 100, 1000 μg/mL; Figure 5B). FITC-tagged goat IgG was used as control protein and showed negative binding to neuronal cell surfaces. FITC-tagged GRGGL peptides appeared to bind to most neurons in the culture.

Figure 5.

A synthetic peptide, GRGGL repeats, binding to neuronal surface. (A) Peptides as surface coating on tissue culture plates for neuronal cultures. (a-d) Representative fluorescence live images of primary rat cortical neurons (live cells in green, dead cells in red) growing on un-coated TCP surfaces (a), compared to TCP surfaces that were coated with GRGGL peptides at 10 μg/mL (b), 100 μg/mL (c), 1000 μg/mL (d). (e) Quantification of neurite lengths of neurons at DIV3. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) FITC-tagged GRGGL peptides applied to DIV5 neurons (counter-stained with DAPI in blue) cultured on TCP-pll surfaces. (f-i) Representative fluorescence images of FITC-tagged mouse IgG (green) used as control protein (f), compared to FITC-tagged GRGGL peptides (green) at 10 μg/mL (g), 100 μg/mL (h), 1000 μg/mL (i). Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Inhibition with GRGGL peptides to neuronal binding to MaSp1 films. (j-m) Representative phase-contrast images of neurons at 3hr post-seeding on MaSp1 films: no peptide control (Sham) (j), compared to co-incubation with GRGGL peptides at 10 μg/mL (k), 100 μg/mL (l), 500 μg/mL (m). Scale bar: 100 μm.

To examine whether GRGGL peptides inhibit neuronal binding to MaSp1, cells were pre-incubated with the peptides before seeding (Figure 5C). At 3hr post-seeding, neurons showed decreasing binding to MaSp1 films at the presence of increasing concentrations of GRGGL peptides. Co-incubation with 100 g/mL peptide showed noticeable decrease of cell density, whereas with 500 g/mL peptide most cells were dead.

Discussion

Unlike silkworm silk, spider silks are historically difficult to obtain due to the territorial nature of spiders that prevents stable production of spider silk via farming spiders in large populations. Recombinant production seems to be a more viable method and is widely used in spider silk research. However current challenges for recombinant spider silk technologies include: 1) Producing recombinant silk protein with the ability to form continuous fibers that have comparable mechanical properties to the native silk. 2) Producing recombinant protein at large scale in a cost-efficient manner. It is generally believed that in order to achieve comparable mechanical properties to native silk, the recombinant silk protein needs to have comparable molecular weight with a similar spinning process that mimics the spider[42, 43]. Various efforts have been made in terms of sequence manipulation[38, 44-46], as well as precise control of spinning conditions[47, 48]. On the other hand, in terms of large scale protein production, recombinant spider silk expression via mammal lactation has advantages over other host organisms that have been previously used for spider silk expression, such as Escherichia coli[49], Pichia pastoris[50], baby hamster kidney (BHK) cell line[51] and tobacco[52]. This transgenic animal approach has industrial levels of protein production with scalability as well as a simple and cost-effective production and purification methodologies.

Recombinant MaSp1 films supported the growth of primary cortical neurons, including surface adhesion, axon outgrowth and network connectivity. Similarly, a miniature recombinant spider silk protein based on the dragline silk of Euprosthenops australis dubbed 4RepCT have been reported to be able to support the growth of human neural stem cells, peripheral neurons and Schwann cells in vitro[22]. For in vivo study, native Nephila dragline silk has been used in artificial nerve constructs as guiding materials for long distance nerve defect repair[53]. Nerve constructs with spider silk enhanced Schwann cell migration, axonal regrowth and remyelination which resulted in the functional recovery of the nerve defect in an adult sheep model. However, these previous studies pointed out that the molecular mechanisms of how this spider silk protein interact and regulate neuron growth are not understood. Both the 4RepCT and the MaSp1 protein have relatively high isoelectric points (8.9 and 10.2, respectively), which means that at physiological pH, they both carry a net positive charge. Neuron cell has been known to have improved adhesion to positively charged surfaces, for example, poly-lysine has been routinely used as coating for 2D neuron tissue culture. Recently, a recombinant silk-elastin chimeric protein with tunable surface charges has also demonstrated the effect of positive charge on neuron morphology[12]. Combining this evidence in previous work with the observations in this study, we concluded that the surface positive charge is the most obvious reason that recombinant MaSp1 supported neuron growth. However, poly-L-lysine carries more positive charges than MaSp1 silk, yet the ability of MaSp1 to binding cell surface NCAM and support neuron cell growth was comparable to poly-L-lysine. Furthermore, analysis of NCAM expression at both mRNA and protein levels indicated upregulation of this neuron specific adhesion molecule. All of these phenomena suggested that there were other factors contributing to the improved adhesion and growth of neuron cells.

Through sequence homology analysis of extracellular matrix proteins such as fibronectin, collagen and laminin, as well as synthetic peptide studies, a series of cell binding motifs that may regulate cell adhesion have been suggested, including the widely used RGD, GFPGER sequences[54-56] as well as rarer LDV, RTD, KQAGD and YRGRD[57]. In contrast, those known sequences are not present in the MaSp1 silk studied here. Instead, a new sequence GRGGL was evaluated here as a putative neuron-interacting motif within the recombinant MaSp1 sequence. GRGGL peptides could also support neuron growth like MaSp1, although the cells displayed a more clustered pattern with shorter axon in cell morphology. Fluorescently tagged peptides when added as solution to neuron cultures were found to bind to cell surfaces directly, indicating this sequence may be able to bind neuron surface receptors. Conversely, when neurons were incubated with the peptides during seeding, cell adhesion to MaSp1 films was significantly inhibited in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that GRGGL peptides directly competes with whole-length MaSp1 for neuronal surface binding. Together, these findings suggest a potential link between specific cell-binding to MaSp1 and NCAM-depending neural cell signaling that results in enhanced neuronal growth. NCAM plays important roles in regulating neuronal growth via its homophilic or heterophilic binding with fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors[58] and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) receptors[59]. Previous study using single residue mutated NCAM indicated that electrostatic interaction played a role in NCAM homophilic interaction[60]. The rat NCAM sequence has a calculated PI of 4.83, so it carries net negative charge in physiology pH. Together with the positively charged MaSp1 substrate, our finding suggests that the heterophilic interaction between NCAM and substrate may also mediated by electrostatic interactions. It is likely that instead of mimicking the neural ECM, MaSp1-based matrices may trigger cell-cell interactions by initiating neural-specific cell binding to substrate, thereby promoting neuronal growth. These findings point to a new direction for designing neural cell-binding sites for recombinant protein biomaterials.

Coating with the synthetic peptides on tissue-culture plates induced neuron adhesion and initial axon outgrowth, but led to cluster formation and shorter axons as the culture progressed, when compared to the extensive neural networks formed on MaSp1 films. These results indicate that neural-specific cell binding alone may not be sufficient for supporting neural network formation. The initial growth was consistent with the significant binding of the peptide to neuronal surfaces. However, compared to the peptide being “tethered” within the MaSp1 sequence, the synthetic peptide may change their spatial distribution during neuronal growth due to their smaller size and higher mobility in solution or as a surface coating (Figure 6). Other studies based on the well-known RGD site-integrin interaction have demonstrated that spatial presentation of cell binding sites at the nano-scale play profound roles in modulating cell adhesion and motility[61]. Our study further demonstrates that physical properties of the matrices affect long-term stability of the binding sites that is important for neural network formation. In our previous study using poly-lysine coated B. mori silk films, we showed a positive correlation between film stiffness and neuronal growth with an optimal Young's modulus > 40 MPa in dry state[10]. In this study, MaSp1 film stiffness was comparable to the optimal stiffness, and showed better neural networks consisting of more connections and thicker bundles compared to the TCP-pll control cultures. Matrix stiffness could counteract axon growth-generated tension, thereby maintaining the stability of neuronal binding. Combined, these studies suggest that neuron-specific surface binding sites need to be presented with neuron-compatible mechanical support, in order to promote long-term neuronal growth and network formation. Furthermore, as suggested previously [62], other material properties such as morphology, roughness and wettability may play roles in regulating cell growth on silk films. While the present study only investigated flat films, future studies to compare various matrices for neuron growth and network formation may be useful.

Figure 6.

Hypothesized mechanism of MaSp1 supporting neuronal growth. Interaction of surface binding ligand GRGGL with neuron cells. (upper) when GRGGL motif is tethered within MaSp1 film, neuron cell spread better and forms larger network. (bottom) synthesized GRGGL peptides have higher mobility which could slides on surface and leads to more clustered cell morphology.

For engineering peripheral nerves, spider silk protein-based nerve conduits have demonstrated capability for nerve guidance, Schwann cell migration, and utility as transplants[24, 63]. For the central nervous system, we have published a series of reports of silkworm silk-based matrices for modulating neuronal growth and function, including alignment, electrical responses, and connectivity, and as brain implants[10, 23]. The present study adds insight on the mechanism of silk protein-neuron interaction; this understanding may facilitate future designs of multi-functional materials for neural engineering.

Conclusions

This study presents evidence that the recombinant MaSp1 silk protein has favorable properties to regulate neuron growth. These properties include both physical regulation e.g. higher stiffness and positive surface charges, as well as biological regulation with primary sequence of protein substrate that interact with neuron surface receptors and upregulate NCAM expression. These findings suggest a mechanism involving surface binding motifs tethered by matrix structure with neuron-compatible mechanical stiffness and provide direct evidence of the dual requirements of physical properties and surface binding sites for neural matrices. Recombinant MaSp1 spider silk matrices may serve as appealing biomaterials for neuron cell culture and may provide new strategies for generating synthetic materials with both physical and biological regulating mechanisms suitable for neural tissue engineering.

Acknowledgement

A. B. and M.D.T contributed equally to this paper; the order was determined alphabetically. We thank the NIH (R01 EB014283, P41 EB002520, R01 EY020856) to D.L.K and USTAR, DOE (DE-SC0004791), NSF (IIP-1318194) to R.V.L for funding support for these studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.Park KI, Teng YD, Snyder EY. The injured brain interacts reciprocally with neural stem cells supported by scaffolds to reconstitute lost tissue. Nat Biotech. 2002;20:1111–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qu C, Mahmood A, Liu XS, Xiong Y, Wang L, Wu H, et al. The treatment of TBI with human marrow stromal cells impregnated into collagen scaffold: Functional outcome and gene expression profile. Brain Research. 2011;1371:129–39. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daly W, Yao L, Zeugolis D, Windebank A, Pandit A. A biomaterials approach to peripheral nerve regeneration: bridging the peripheral nerve gap and enhancing functional recovery. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 2012;9:202–21. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Cooke MJ, Sachewsky N, Morshead CM, Shoichet MS. Bioengineered sequential growth factor delivery stimulates brain tissue regeneration after stroke. Journal of Controlled Release. 2013;172:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ju Y-E, Janmey PA, McCormick ME, Sawyer ES, Flanagan LA. Enhanced neurite growth from mammalian neurons in three-dimensional salmon fibrin gels. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2097–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKinnon DD, Brown TE, Kyburz KA, Kiyotake E, Anseth KS. Design and Characterization of a Synthetically Accessible, Photodegradable Hydrogel for User-Directed Formation of Neural Networks. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:2808–16. doi: 10.1021/bm500731b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georges PC, Miller WJ, Meaney DF, Sawyer ES, Janmey PA. Matrices with compliance comparable to that of brain tissue select neuronal over glial growth in mixed cortical cultures. Biophysical journal. 2006;90:3012–8. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch D, Rosoff WJ, Jiang J, Geller HM, Urbach JS. Strength in the periphery: growth cone biomechanics and substrate rigidity response in peripheral and central nervous system neurons. Biophysical journal. 2012;102:452–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins AM, De Laporte L, Tortelli F, Spedden E, Staii C, Atherton TJ, et al. Silk Hydrogels as Soft Substrates for Neural Tissue Engineering. Advanced functional materials. 2013;23:5140–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang-Schomer MD, Hu X, Hronik-Tupaj M, Tien LW, Whalen MJ, Omenetto FG, et al. Film-Based Implants for Supporting Neuron–Electrode Integrated Interfaces for The Brain. Advanced functional materials. 2014;24:1938–48. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201303196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franze K. The mechanical control of nervous system development. Development (Cambridge, England) 2013;140:3069–77. doi: 10.1242/dev.079145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu X, Tang-Schomer MD, Huang W, Xia XX, Weiss AS, Kaplan DL. Charge-Tunable Silk-Tropoelastin Protein Alloys That Control Neuron Cell Responses. Advanced functional materials. 2013;23:3875–84. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201202685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiryushko D, Berezin V, Bock E. Regulators of neurite outgrowth: role of cell adhesion molecules. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1014:140–54. doi: 10.1196/annals.1294.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutishauser U, Hoffman S, Edelman GM. Binding properties of a cell adhesion molecule from neural tissue. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1982;79:685–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.2.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandig M, Rao Y, Siu CH. The homophilic binding site of the neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM is directly involved in promoting neurite outgrowth from cultured neural retinal cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:14841–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams EJ, Furness J, Walsh FS, Doherty P. Activation of the FGF receptor underlies neurite outgrowth stimulated by L1, N-CAM, and N-cadherin. Neuron. 1994;13:583–94. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JQ, Bennett V. Ankyrin binding activity shared by the neurofascin/L1/NrCAM family of nervous system cell adhesion molecules. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:27163–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santuccione A, Sytnyk V, Leshchyns'ka I, Schachner M. Prion protein recruits its neuronal receptor NCAM to lipid rafts to activate p59fyn and to enhance neurite outgrowth. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;169:341–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maness PF, Schachner M. Neural recognition molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily: signaling transducers of axon guidance and neuronal migration. Nature neuroscience. 2007;10:19–26. doi: 10.1038/nn1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruggiero F, Koch M. Making recombinant extracellular matrix proteins. Methods (San Diego, Calif) 2008;45:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An B, Kaplan DL, Brodsky B. Engineered recombinant bacterial collagen as an alternative collagen-based biomaterial for tissue engineering. Frontiers in Chemistry. 2014:2. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewicka M, Hermanson O, Rising AU. Recombinant spider silk matrices for neural stem cell cultures. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7712–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hronik-Tupaj M, Raja WK, Tang-Schomer M, Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. Neural responses to electrical stimulation on patterned silk films. Journal of biomedical materials research Part A. 2013;101:2559–72. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radtke C, Allmeling C, Waldmann KH, Reimers K, Thies K, Schenk HC, et al. Spider silk constructs enhance axonal regeneration and remyelination in long nerve defects in sheep. PloS one. 2011;6:e16990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis RV. Spider Silk: Ancient Ideas for New Biomaterials. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3762–74. doi: 10.1021/cr010194g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gosline JM, DeMont ME, Denny MW. The structure and properties of spider silk. Endeavour. 1986;10:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu M, Lewis R. Structure of a protein superfiber: spider dragline silk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7120–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinman M, Lewis RV. Isolation of a clone encoding a second dragline silk fibroin. Nephila clavipes dragline silk is a two-protein fiber. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19320–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashi CY, Shipley NH, Lewis RV. Hypotheses that correlate the sequence, structure, and mechanical properties of spider silk proteins. Int J Biol Macromol. 1999;24:271–5. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(98)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garb JE, Ayoub NA, Hayashi CY. Untangling spider silk evolution with spidroin terminal domains. BMC evolutionary biology. 2010;10:243. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisoldt L, Thamm C, Scheibel T. The role of terminal domains during storage and assembly of spider silk proteins. Biopolymers. 2012;97:355–61. doi: 10.1002/bip.22006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ittah S, Cohen S, Garty S, Cohn D, Gat U. An essential role for the C-terminal domain of a dragline spider silk protein in directing fiber formation. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1790–5. doi: 10.1021/bm060120k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KS, Kim BY, Je YH, Woo SD, Sohn HD, Jin BR. Molecular cloning and expression of the C-terminus of spider flagelliform silk protein from Araneus ventricosus. J Biosci. 2007;32:705–12. doi: 10.1007/s12038-007-0070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tucker CL, Jones JA, Bringhurst HN, Copeland CG, Addison JB, Weber WS, et al. Mechanical and Physical Properties of Recombinant Spider Silk Films Using Organic and Aqueous Solvents. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:3158–70. doi: 10.1021/bm5007823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Kim H-J, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL. Stem cell-based tissue engineering with silk biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2006;27:6064–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho S-Y, Chao C-Y, Huang H-L, Chiu T-W, Charoenkwan P, Hwang E. NeurphologyJ: An automatic neuronal morphology quantification method and its application in pharmacological discovery. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang W, Edenzon K, Fernandez L, Razmpour S, Woodburn J, Cebe P. Nanocomposites of poly(vinylidene fluoride) with multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2010;115:3238–48. [Google Scholar]

- 38.An B, Jenkins JE, Sampath S, Holland GP, Hinman M, Yarger JL, et al. Reproducing natural spider silks' copolymer behavior in synthetic silk mimics. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:3938–48. doi: 10.1021/bm301110s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruoslahti E, Pierschbacher MD. Arg-Gly-Asp: a versatile cell recognition signal. Cell. 1986;44:517–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knight CG, Morton LF, Peachey AR, Tuckwell DS, Farndale RW, Barnes MJ. The collagen-binding A-domains of integrins alpha(1)beta(1) and alpha(2)beta(1) recognize the same specific amino acid sequence, GFOGER, in native (triple-helical) collagens. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:35–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Virgintino D, Perissinotto D, Girolamo F, Mucignat MT, Montanini L, Errede M, et al. Differential distribution of aggrecan isoforms in perineuronal nets of the human cerebral cortex. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2009;13:3151–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00694.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia X, Qian Z, Ki C, Park Y, Kaplan DL, Lee S. Native-sized recombinant spider silk protein produced in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli results in a strong fiber. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14059–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003366107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vollrath F, Knight DP. Liquid crystalline spinning of spider silk. Nature. 2001;410:541–8. doi: 10.1038/35069000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adrianos SL, Teulé F, Hinman MB, Jones JA, Weber WS, Yarger JL, et al. Nephila clavipes Flagelliform Silk-Like GGX Motifs Contribute to Extensibility and Spacer Motifs Contribute to Strength in Synthetic Spider Silk Fibers. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:1751–60. doi: 10.1021/bm400125w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hinman M, Teulé F, Perry D, An B, Adrianos S, Albertson A, et al. Asakura T, Miller T, editors. Modular Spider Silk Fibers: Defining New Modules and Optimizing Fiber Properties. Biotechnology of Silk: Springer Netherlands. 2014:137–64. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teulé F, Addison B, Cooper AR, Ayon J, Henning RW, Benmore CJ, et al. Combining flagelliform and dragline spider silk motifs to produce tunable synthetic biopolymer fibers. Biopolymers. 2012;97:418–31. doi: 10.1002/bip.21724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.An B, Hinman MB, Holland GP, Yarger JL, Lewis RV. Inducing β-sheets formation in synthetic spider silk fibers by aqueous post-spin stretching. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:2375–81. doi: 10.1021/bm200463e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rammensee S, Slotta U, Scheibel T, Bausch AR. Assembly mechanism of recombinant spider silk proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:6590–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709246105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia XX, Xu Q, Hu X, Qin G, Kaplan DL. Tunable self-assembly of genetically engineered silk--elastin-like protein polymers. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:3844–50. doi: 10.1021/bm201165h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fahnestock SR, Bedzyk LA. Production of synthetic spider dragline silk protein in Pichia pastoris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;47:33–9. doi: 10.1007/s002530050884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lazaris A, Arcidiacono S, Huang Y, Zhou JF, Duguay F, Chretien N, et al. Spider silk fibers spun from soluble recombinant silk produced in mammalian cells. Science (New York, NY) 2002;295:472–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1065780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Menassa R, Zhu H, Karatzas CN, Lazaris A, Richman A, Brandle J. Spider dragline silk proteins in transgenic tobacco leaves: accumulation and field production. Plant Biotechnol J. 2004;2:431–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2004.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allmeling C, Jokuszies A, Reimers K, Kall S, Choi CY, Brandes G, et al. Spider silk fibres in artificial nerve constructs promote peripheral nerve regeneration. Cell Proliferation. 2008;41:408–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruoslahti E, Pierschbacher MD. New perspectives in cell adhesion: RGD and integrins. Science (New York, NY) 1987;238:491–7. doi: 10.1126/science.2821619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seo N, Russell BH, Rivera JJ, Liang X, Xu X, Afshar-Kharghan V, et al. An engineered alpha1 integrin-binding collagenous sequence. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:31046–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.An B, DesRochers TM, Qin G, Xia X, Thiagarajan G, Brodsky B, et al. The influence of specific binding of collagen–silk chimeras to silk biomaterials on hMSC behavior. Biomaterials. 2013;34:402–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuhbier JW, Allmeling C, Reimers K, Hillmer A, Kasper C, Menger B, et al. Interactions between Spider Silk and Cells – NIH/3T3 Fibroblasts Seeded on Miniature Weaving Frames. PloS one. 2010;5:e12032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kiselyov V. NCAM and the FGF-Receptor. In: Berezin V, editor. Structure and Function of the Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule NCAM. Springer; New York: 2010. pp. 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paratcha G, Ledda F, Ibáñez CF. The Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule NCAM Is an Alternative Signaling Receptor for GDNF Family Ligands. Cell. 113:867–79. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00435-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rao Y, Wu XF, Yip P, Gariepy J, Siu CH. Structural characterization of a homophilic binding site in the neural cell adhesion molecule. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:20630–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maheshwari G, Brown G, Lauffenburger DA, Wells A, Griffith LG. Cell adhesion and motility depend on nanoscale RGD clustering. Journal of Cell Science. 2000;113:1677–86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Widhe M, Bysell H, Nystedt S, Schenning I, Malmsten M, Johansson J, et al. Recombinant spider silk as matrices for cell culture. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9575–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang W, Begum R, Barber T, Ibba V, Tee NCH, Hussain M, et al. Regenerative potential of silk conduits in repair of peripheral nerve injury in adult rats. Biomaterials. 2012;33:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]