Abstract

Objective

To identify factors important to parents making decisions for their critically ill child.

Design

Prospective cross-sectional study.

Setting

Single center, tertiary care PICU.

Subjects

Parents making critical treatment decisions for their child.

Intervention

One-on-one interviews that used the Good Parent Tool-2 open-ended question that asks parents to describe factors important for parenting their ill child and how clinicians could help them achieve their definition of “being a good parent” to their child. Parent responses were analyzed thematically. Parents also ranked themes in order of importance to them using the Good Parent Ranking Exercise.

Measurement and Main Results

Of 53 eligible parents, 43 (81%) participated. We identified nine themes through content analysis of the parent’s narrative statements from the Good Parent Tool. Most commonly (60% of quotes) components of being a good parent described by parents included focusing on their child’s quality of life, advocating for their child with the medical team, and putting their child’s needs above their own. Themes key to parental decision making were similar regardless of parent race and socioeconomic status or child’s clinical status. We identified nine clinician strategies identified by parents as helping them fulfill their parenting role, most commonly, parents wanted to be kept informed (32% of quotes). Using the Good Parent Ranking Exercise, fathers ranked making informed medical decisions as most important, whereas mothers ranked focusing on the child’s health and putting their child’s needs above their own as most important. However, mothers who were not part of a couple ranked making informed medical decisions as most important.

Conclusion

These findings suggest a range of themes important for parents to “be a good parent” to their child while making critical decisions. Further studies need to explore whether clinician’s knowledge of the parent’s most valued factor can improve family-centered care.

Keywords: communication, decision making, family, palliative care, parents, qualitative research

Life-altering treatment decisions for critically ill children rely on communication between parents and PICU clinicians (1). Most parents report a preference for open communication (2, 3), framed by shared decision making when discussing treatment options with clinicians (4–6). Shared decision making, where the clinicians, parent, and patient work together to choose the best option for the child, is optimized when the family’s values and preferences around treatment decisions are central to the discussion (7, 8). Despite the call for a family-centered approach to decision making (9, 10) and an increased need to understand family values and preferences, there are no interventions in pediatric critical care that aim to improve exploration of factors important to parents during decision making.

The Good Parent Tool (11), an empirically based decision-making construct, is a promising possibility to explore parent’s values and preferences around decision making in the PICU. In describing their parental responsibilities, parents of children with cancer making end-of-life decisions reported trying to “be a good parent” in making care decisions in their child’s best interests. The definition of being a good parent was developed into eight themes using content analysis of parent narrative responses. Of these themes, the two most common were “doing right by my child” and “being there for my child.” Achievement of their internal definition of being a good parent was described by the parent as helping them cope with their child’s clinical situation (12).

The Good Parent Tool has been used effectively to elicit themes around end-of-life decision making among non- Hispanic white mothers of children with incurable cancer (11). We do not know if the themes that influence parents’ definition of being a good parent differ in a diverse population of parents of children in the PICU involved in broader treatment decisions. The primary objective of this study was to use the Good Parent Tool to elicit factors important to parents of children in the PICU involved in a critical treatment decision for their child and develop these factors into themes. We also aimed to identify clinician strategies that may help parents fulfill their individualized definition of their responsibilities for their ill child while in the PICU.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting, Design, and Participants

This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted in the PICU of a single urban, tertiary medical center from June 2012 to April 2013. Institutional review board approval was obtained. English-speaking parents of children in the PICU for whom a family conference was being convened to discuss a clinical treatment decision for their child were eligible for enrollment. A critical treatment decision was defined as a decision to initiate, escalate, or withdraw life-sustaining therapies and included management decisions, such as tracheostomy placement, gastrostomy tube placement, and other procedures, resuscitation status, and complex discharge planning.

Each weekday, the PICU attending physician on service was approached by study investigators to determine whether he/she anticipated conducting a family conference to discuss a critical treatment decision with parents of children in the PICU. We limited enrollment to weekdays because preliminary work demonstrated most decision-making family conferences occurred during the weekday when consultants and support staff are most available to parents. Prior to approaching parents, the study investigator obtained permission from the PICU attending, social worker, and bedside nurse. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent prior to the family conference, and parent interviews were conducted within 24 hours of the conference. Parents were defined as adults with primary decision-making responsibilities for the critically ill child. This person(s) may be the biological parent, adopted or foster parent, or member of the extended family. Couples were defined as two parents who both participate in decision making for their child, regardless of marital status or sex. Parents could be interviewed together or separately, depending on their preference.

Data Collection

Data collected from patients were obtained from the patient’s medical chart and included demographics, PICU length of stay, Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) score, primary diagnosis, and presence of a complex chronic condition, as defined by Feudtner et al (13). Demographic data were also collected from parents using a demographics survey. Within 24 hours of completion of the family conference, parents were asked to complete a survey (the Good Parent Tool) and a ranking exercise (the Good Parent Ranking Exercise), regarding their parental role to their child in the PICU. The Good Parent Tool is a two-question open-ended survey completed by one-on-one interview. Study investigators read the following statements: “In our previous studies with parents who face making a difficult decision, such as the one you are considering on behalf of your child, we learned that parents make their decisions to benefit their child in some way. These parents described their decision making as ‘doing what a good parent would do’ or ‘deciding as a good parent would.’ It is important to staff to do all they can to support your definition of what a good parent is or what a good parent would do. 1) Please share with me your definition of being a good parent for your child at this point in your child’s life. 2) Please describe for me the actions from the staff that would help you in your efforts to be a good parent to your child now.” Parent responses were written down and confirmed by reading the statements back to the parent. Parents were interviewed only once.

The Good Parent Ranking Exercise (C. Feudtner, unpublished observation, 2009) is a 5-minute exercise that results in a best/worst scaling called maximum difference scaling (14). Eight of the 12 potential Good Parent priorities were drawn from the original Good Parent Tool, which was developed in the pediatric oncology setting regarding end-of-life decision making. These eight potential priorities were reviewed by members of an interdisciplinary palliative care team and by a focus group of parents of children, including children living with serious illness, resulting in four additional potential priorities that may be pertinent to parents making decisions that were not endof- life decisions. The four additional items include “keeping a positive outlook,” “keeping a realistic outlook,” “focusing on my child’s health,” and “focusing on my child having as long a life as possible.” The 12 potential good parent priorities are arrayed into 12 sets of four items each—selecting among the many permutations and combinations of item sets that provide equal representation of all 12 items. For each set of four items, we then asked the parent to select the “most important” and “least important” items. The Good Parent Ranking Exercise enables quantitative analysis of an individual’s compiled responses, resulting in an important score for each item.

Data Analysis

A mixed methods approach was used. The primary qualitative analytic method used was content analysis (15), as it allows for the intended meaning of narrative content to be systematically extracted and described. The resulting codes were described in terms of meaning and frequency. The meaning and frequency of each code were examined at the level of the total parent sample, by gender and by couples. Two independent coders evaluated the parent responses to the Good Parent Tool to establish recurring themes and to formulate definitions for these themes. Previously published codes for the Good Parent Tool were carefully examined for their conceptual match with our parent interviews and were used when they matched parent interview data in this study. New codes were developed for content that represented new areas of meaning not identified in previous studies. Each individual parent quotation was repeatedly compared with other parent responses within and across all parent interviews to ensure the code accurately described the quotes and to assess for code overlapping. Codes with overlapping meaning were subsequently combined and the definition altered accordingly to allow for a reduced number of unique codes. After reduction of the codes, a random sample of 10% of the quotes was selected for interrater reliability between the two coders. The Cohen’s κ was 0.91 (p < 0.001). Parents were enrolled until data saturation was reached. Saturation was determined when no new codes emerged after five consecutive interviews.

Quantitative analysis of the Good Parent Ranking Exercise was performed using MaxDiff/Web v.6.0 software (Sawtooth software, Orem, UT), which uses multinomial logistic regression modeling, employed within a hierarchical Bayes estimation framework, to calculate the probability of choosing a specific priority as the best or the worst for each individual parent and for the entire sample of parents. The overall average rankings for the entire sample of parents provide a summary measure, whereas the individual rankings can be used as predictors for identifying groups of similar parents, such as by race, gender, or treatment decision. The 12 priorities are then rank ordered on a relative scale, based on the weights that each priority had in the regression models, with the scores for all of the priorities summing to 100 points.

Descriptive statistics were applied to demographic data. Continuous data were expressed as means and sds or medians and interquartile ranges as appropriate. Chi-square test or Fisher exact test were applied, as appropriate, to categorical data with findings expressed as absolute counts and percentages when comparing parent and patient demographic and clinical characteristics with qualitative parent responses. Data were analyzed using the Stata 11.0 software package (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

During the study period, there were 53 eligible parents of 34 patients. Three parents (6%) declined to participate secondary to the critical status of their child, six (11%) consented, but did not complete the interview due to rapid clinical deterioration of their child, and one parent (2%) submitted an uninterpretable Good Parent Ranking Exercise, which was excluded from analysis. We had complete data for 43 parents of 29 children (81%). There were no missing data, and the mean interview and Good Parent Ranking Exercise completion time was 8 minutes. Of the parents surveyed, 25 of 43 (58%) were mothers and 30 of 43 parents (70%) were couples, of which 22 of 30 (73%) were married. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients (Table 1) and parents (Table 2) revealed that patient and parent diversity reflect the demographics of the community we serve in Washington, DC. Although the mortality rate in our PICU was 1.8% and average PRISM score was 0.98% in 2011–2012, the mortality rate and PRISM score of the cohort of children who had a treatment decision conference was 34% and 4%, respectively. The most frequent decision was tracheostomy placement (10, 35%). Other procedures (7, 24%) included gastrostomy tube placement (n = 2), high-risk lung biopsy in an oncology patient (n = 1), second bone marrow transplant (n = 1), appendectomy (n = 1), bronchopulmonary fistula repair (n = 1), and subtotal colon resection (n = 1). Discussion about resuscitation status (6, 21%) included decisions to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining therapies. Discharge planning (3, 10%) involved discussions about the patient’s disposition to home on hospice (n = 2) and rehabilitation facility preference for a child with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus infection who recovered from extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and a below the knee amputation (n = 1). There were conferences in which the attending physician identified more than one primary purpose of the family conference (3, 10%). These decisions included tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube placement (n = 2) and chemotherapy options with tracheostomy placement (n = 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Patient Characteristics | n = 29 (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender female | 16 (55) |

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 4 (1.4–10) |

| PICU length of stay, d, median (IQR) | 29 (16.5–46.5) |

| Pediatric Risk of Mortality Score median (range) | 4 (0.5–12) |

| Disposition from hospital | |

| Home | 10 (34) |

| Chronic care facility | 7 (25) |

| Hospice | 2 (7) |

| Mortality | 10 (34) |

| Primary diagnostic category | |

| Hematologic/oncologic | 10 (34) |

| Respiratory | 6 (21) |

| Neurologic | 4 (14) |

| Trauma | 4 (14) |

| Gastrointestinal | 2 (7) |

| Metabolic/genetic | 2 (7) |

| Sepsis/shock | 1 (3) |

| Complex chronic condition present | 18 (62) |

| Treatment decision considered by parents | |

| Tracheostomy placement | 10 (35) |

| Other proceduresa | 7 (24) |

| Resuscitation status | 6 (21) |

| Discharge planning | 3 (10) |

| Multiple decisionsb | 3 (10) |

IQR = interquartile range.

Other procedures included gastrostomy tube placement (n = 2), high-risk lung biopsy in an oncology patient (n = 1), second bone marrow transplant (n = 1), appendectomy (n = 1), bronchopulmonary fistula repair (n = 1), and subtotal colon resection (n = 1).

Multiple decisions included tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube placement (n = 2) and chemotherapy options with tracheostomy placement (n = 1).

Table 2.

Parent Demographic Characteristics

| Parent Characteristics | n = 43 (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender female | 25 (58) |

| Age, yr, mean (sd) | 38 (11.6) |

| Race | |

| African-American | 28 (65) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 11 (25) |

| Asian | 2 (5) |

| Other | 2 (5) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 22 (51) |

| Single | 21 (49) |

| Couple | 30 (35) |

| Religion | |

| Christian | 27 (63) |

| Jewish | 2 (5) |

| Other | 8 (18) |

| None designated | 6 (14) |

| Education completed | |

| Less than college | 16 (37) |

| Some college | 11 (26) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 9 (21) |

| Postgraduate degree | 7 (16) |

| Household income | |

| $0–$29,999 | 9 (21) |

| $30,000–$49,999 | 5 (11) |

| $50,000–$89,999 | 11 (26) |

| $90,000 or more | 7 (16) |

| Would rather not say | 11 (26) |

Nine key themes important in decision making for their ill child were coded from 132 individual quotes using the Good Parent Tool (Table 3). The most common themes reported were “focusing on my child’s quality of life,” “advocating for my child,” and “putting my child’s needs above my own” (60% of quotes). There were no associations between parental race, age, religion or socioeconomic status, and parental theme identified. We also did not find any associations between underlying disease, presence of complex chronic condition, or demographic variables of patients and parent theme identified (p > 0.05, data not shown). “Having a legacy” is the only new theme that emerged in our sample compared with the originally established Good Parent Tool. Parents who were part of a couple identified an average of 3.6 themes, of which approximately 22% of the themes were identified by both parents. Single parents identified an average of 1.6 themes important to them while parenting their ill child.

Table 3.

Themes of Being a Good Parent During Critical Decision Making for Their Child

| Themes | Definition | Frequency, n = 132 (%) |

Sample Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focusing on my child’s quality of life | Parent desires the ill child to be comfortable with minimal pain or suffering | 28 (21) | I don’t want him to feel as if he is leading a half life |

| Advocating for my child | Parent nurtures the child through the illness and alerts the clinical team to the child’s physical, emotional, and spiritual needs | 26 (20) | A good parent is someone who wants to understand the child’s needs and makes sure they (the child) get it |

| Putting my child’s needs above my own | Parent strives to make quality, unselfish decisions in the best interest of the ill child even if there’s conflict with the parent’s wishes | 25 (19) | I don’t want to cause her death because it hurts too much, but I need to figure out what she needs instead of what I need |

| Making informed medical care decisions | Parent must have the data to actively participate in making choices that benefit the ill child, are safe, and will be supported by the rest of the family | 18 (14) | Gathering as much information as possible to make the best long-term decisions for her |

| Staying at my child’s side | Parent prefers being at the bedside in case the child awakens, even if the ill child does not seem to know the parent is present | 14 (11) | Being physically present with him every step of the way and holding his hand literally and figuratively |

| Focusing on my child’s health and longevity | Parent seeks to initiate every possible action to save the ill child with hopes that the child will get healthy | 10 (8) | Doing whatever you can to save your child |

| Making sure my child feels loved | Parent needs the ill child to know he is cherished to the last possible moment of life | 7 (5) | I want to give her our love to the last minute |

| Maintaining faith | Parent believes in a higher power and trusts that the child will be healed | 2 (1) | Most importantly, it means being faithful and praying for my son’s healing and exercising faith through advocacy and hands-on care |

| Having a legacy | Parent wants to honor the ill child’s memory by allowing the child to live on in someone else | 2 (1) | Allowing her to live on in someone else |

When asked to describe the actions from staff that would “help you parent your ill child,” parent responses yielded 111 quotes from which nine themes were derived. “Keeping us informed” was the most frequent theme identified (32%) (Table 4) followed by “be attentive,” “keep providing good care,” and “nothing else” (32%). Parental desire to “be allowed to parent their child” by assisting in daily care activities was the only new theme specific to clinician actions that emerged in our PICU study population in comparison with the previous study in an oncology population (11). Three themes identified in the previous study were absent in our sample: staff asking about spirituality, conveying hope, and including the child during decision making.

Table 4.

Clinician Strategies to Support Parent’s Efforts in Being a Good Parent

| Strategy | Definition | Frequency, n = 111 (%) |

Sample Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keep me informed | Parent requests open, frequent communication that uses simple language, includes all the facts and provides answers to questions | 36 (32) | Give us all the options. It makes it easy to help her Explain it to me. That empowers me to have better knowledge of her illness |

| Be attentive | Parent wants the staff to provide the ill child with the same care, engagement, and devotion as they do for a healthy child | 13 (12) | A focus on her while avoiding Facebook and excessive texting |

| Keep providing good care | Parent is appreciative of staff and knows they are doing the best they can to heal the ill child | 13 (12) | I wouldn’t change anything You’ve been doing your best |

| Nothing | Parent believes care of the ill child is the sole responsibility of the parent | 11 (10) | Nothing. It’s all on me |

| Be considerate | Parent wishes the staff to show common courtesies, such as introducing themselves, listening to the family, and keeping promises | 9 (8) | Having a doctor really take the time to listen to the family about their child and their family |

| Have a team approach | Parent prefers when the child and family’s values are incorporated into the staff’s recommendations for care of the ill child | 9 (8) | He said “I think.” I want to hear “we think.” He didn’t ask our opinion |

| Provide support | Parent values comfort and reassurance from the clinical team to allow the parent to focus on the ill child | 8 (7) | They’ve made me as comfortable as possible, which has made me able to support her |

| Be honest | Parent expects truthful interactions without masking information, appreciates when the team admits they don’t know the answers but takes action to find the answers | 8 (7) | Give us the truth I want to hear the good and bad to better prepare |

| Let me be a parent to my child | Parent wants to participate in the everyday care of the ill child and strives to maintain normalcy | 4 (4) | I want to help with whatever I can Empower me to care for my son |

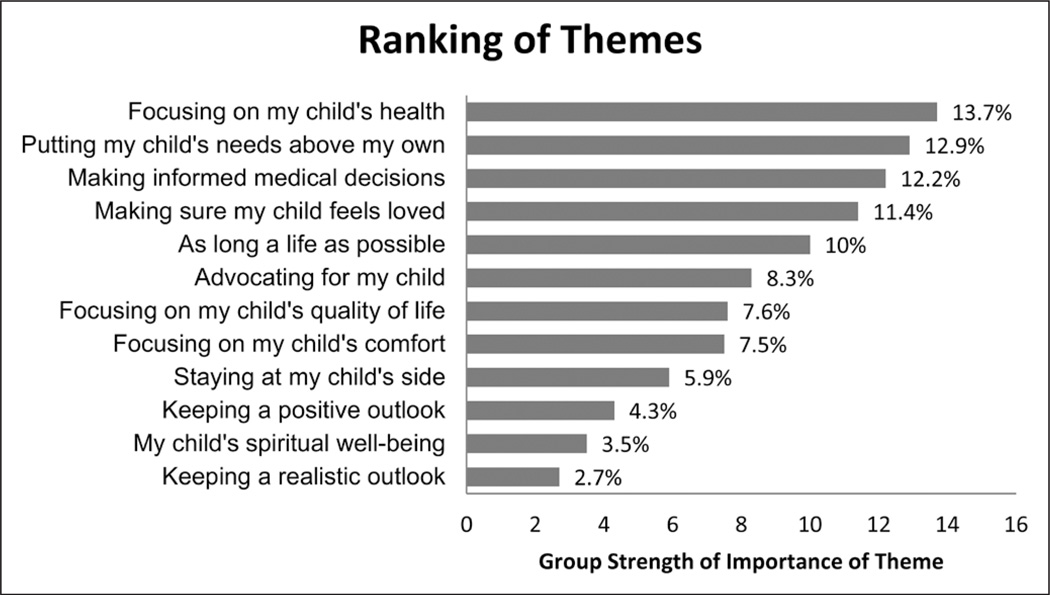

The Good Parent Ranking Exercise, which enables parents to rank the themes in order of most important to least important, revealed that at the group level, parents identified “focusing on my child’s health,” “putting my child’s needs above my own,” “making informed medical decisions,” and “making sure my child feels loved” (50%) (Fig. 1) as the top four most important. The 12 ranking themes presented in Figure 1 are on a relative scale out of 100 points, and scores represent the strength of the groups’ preferences. The ranking takes into account the relative importance of each of the 12 themes when compared with each other. When looking at ranking of the themes at the group level stratified by gender, we found an association between gender of the parent and the most important theme in parental decision making using chi-square analysis. Among the top four ranking themes, the category making informed medical decisions was ranked most important theme by fathers 75% of the time and by mothers 25% of the time (p = 0.045). All the mothers who identified this category as most important were mothers not part of a couple. Mothers who were part of a couple ranked the category focusing on my child’s health as most important 75% of the time. At the individual level, the top four themes ranked as most important by each parent using the Good Parent Ranking Exercise frequently matched at least one of the themes identified by the same parent using the Good Parent Tool (35 of 43, 81%).

Figure 1.

Ranking of potential priorities most important to parents during decision making. The scores for each of the potential priorities are relative to each other, such that a priority with a score of 10 is twice as likely to be chosen as being important (and not chosen as being least important) as is a priority with a score of 5.

DISCUSSION

Parents of critically ill children, regardless of race, socioeconomic status, gender, age, religion, underlying diagnosis, and treatment decision being considered identified their individual meaning of being a good parent to their child using the Good Parent Tool. Parents described the themes of “putting my child’s needs first,” “advocating for my child with the clinical team,” and “focusing on my child’s quality of life” as most important during critical decision making. These results support the findings of prior studies using the Good Parent Tool in parents of children with cancer (11, 12) and expand knowledge of parent perspectives by including a diverse group of mothers, fathers, and couples. Prior studies that have explored parents’ perception of their role in the PICU have also found that being present, forming a partnership with the medical team based on honesty, and being informed are highly valued themes we found present in our study as well (16–19).

Parents identified efforts the clinical team can initiate to help fulfill their internal definition of being a good parent to their child while in the PICU. These strategies clustered into three broad categories: 1) strategies that promote open communication in a team approach, including the clinical team, parents, and child; 2) strategies that encourage the empathetic side of critical care, such as being attentive, considerate, and honest; and 3) strategies that parents currently benefit from and would not change as seen in responses of keep providing good care and there is nothing else the clinical team can do. These results are similar to other studies that document parents’ preferences around decision making in that parents frequently report the desire to have open, updated communication and for clinicians to show empathy (4, 20–23). One important strategy that was absent in our study was that our parents did not report a desire for the staff to inquire about spirituality. Although other studies have reported the importance of spiritual support in the PICU (24, 25), spirituality was ranked eighth of 12 themes in terms of importance to parents in our study. This difference may be related to our research method which included a ranking that placed spirituality in comparison to another theme such as being at my child’s side. Previous studies reporting the importance of spirituality involved bereaved parents or parents making end-of-life decisions (26, 27). Parents making broader critical care decisions, such as those in our study, may not lean as heavily on spiritual support as parents making end-of-life decisions.

We anticipated that parents of children with complex chronic conditions might have different definitions of parenting an ill child compared with parents of children with acute illnesses, such as traumatic injuries, because parents of children with chronic conditions may have had more time to think about their role as a parent of an ill child. We were surprised to find that regardless of the acuteness of the illness, parents expressed similar definitions of being a good parent to their ill child, which speaks to the generalizability of the Good Parent Tool in that it can be used in a broader PICU population.

We were concerned that the term “being a good parent” may offend some parents when introducing the concept to parents. We found that parents were not offended by the title and often embraced it because it accurately described how they see their role in the child’s illness. Being a good parent is a parent-derived term that we acknowledge may be concerning for some others, but the low refusal rate (6%) confirms that asking parents these value-based questions during the decision-making process is feasible and welcomed by parents.

The mixed methods design allowed us to compare qualitative data obtained from the Good Parent Tool with quantitative data from the Good Parent Ranking Exercise. “Putting my child’s needs above my own” and “making informed medical decisions” were common themes of both surveys, of which there appeared to be a gender association. Overall, fathers reported their ability to make informed medical decisions as most important. Mothers who were part of a couple focused more on the child’s health and the child’s needs, whereas mothers who did not identify as part of a couple reported making informed medical decisions, similar to the fathers in our study. We suspect that mothers who are part of a couple also value making informed decisions, but having a partner take on that role may have allowed the mother to focus more on the immediate physical and emotional needs of their ill child. On average, a couple identified an average of 3.6 themes important to them, of which there was minimal overlap between the themes chosen by the mother and father, while parents not part of a couple identified an average of 1.6 themes. This finding may demonstrate a conscious or subconscious strategy by parents to focus on different themes such that together they cover a wider range of themes that are important to parenting their child and making difficult decisions. Parents who made decisions independently did not have the benefit of a second parent to balance all the themes he/she may have deemed important.

There are several limitations to this study. We did not include Spanish-speaking parents, which represents a significant portion of our general PICU population (20%). We chose to include only English-speaking parents because the Good Parent Tool and Good Parent Ranking Exercise have previously been validated among English speakers only. Although our study population was quite diverse in terms of parent and patient demographics, the ability to generalize these results is limited by not including Spanish-speaking parents, conducting this study at a single site, and having a large population of children with complex chronic conditions (62%) compared with children with acute illnesses. Of the 15 couples who participated in our study, three were interviewed together. The survey responses of these couples may have been influenced by one another and may not be independent. In addition, the small number of parents who identified “maintaining faith” (n = 2) and “having a legacy” (n = 2) suggests that these themes are not as grounded in the data as our other themes. Finally, six parents were not approached for survey completion after they had consented to participation due to clinical deterioration of their child. We do not know if parental themes for these parents differ from those themes of our sample that completed surveys, but we thought it important to respect the needs of the parents to focus on their role as parents.

CONCLUSION

The Good Parent Tool elicits factors important to parents of children in the PICU involved in a broad range of critical treatment decisions for their child. Although mothers who are part of a couple report caretaking themes as most important to them, fathers who are part of a couple and mothers who are not part of a couple report being kept informed as most important. Parents overall want the clinical team to keep them informed with honest, frequent communication. Future studies need to explore the impact of using the Good Parent Tool to elicit a parent’s individualized views on factors important to them while making decisions and potentially improve parent- clinician communication in the PICU.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank James W. Womer, BA, for his assistance.

Supported, in part, by NICHD (grant number 5K12HD047349-08) and NINR (grant number 1RO1H5018425).

Dr. October received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Her institution received grant support from the NIH and NICHD. Dr. Feudtner received grant support from NIH R01 (developed the GP quantitative methodology with NIH support) and received support for article research from the NIH.

Footnotes

This work was performed at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC.

The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.October TW, Watson AC, Hinds PS. Characteristics of family conferences at the bedside versus the conference room in pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:e135–e142. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318272048d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon C, Barton E, Meert KL, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network: Accounting for medical communication: Parents’ perceptions of communicative roles and responsibilities in the pediatric intensive care unit. Commun Med. 2009;6:177–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levetown M. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics: Communicating with children and families: From everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1441–e1460. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madrigal VN, Carroll KW, Hexem KR, et al. Parental decision-making preferences in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2876–2882. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825b9151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Osorio CA, Dominguez-Cherit G. Medical decision making: Paternalism versus patient-centered (autonomous) care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:708–713. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328315a611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: A consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:953–963. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: Revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiks AG, Jimenez ME. The promise of shared decision-making in paediatrics. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1464–1466. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truog RD, Meyer EC, Burns JP. Toward interventions to improve end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S373–S379. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237043.70264.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipstein EA, Brinkman WB, Britto MT. What is known about parents’ treatment decisions? A narrative review of pediatric decision making. Med Decis Making. 2012;32:246–258. doi: 10.1177/0272989X11421528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5979–5985. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maurer SH, Hinds PS, Spunt SL, et al. Decision making by parents of children with incurable cancer who opt for enrollment on a phase I trial compared with choosing a do not resuscitate/terminal care option. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3292–3298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: A population-based study of Washington State, 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The MaxDiff/Web v6.0. Sawtooth Software. [Accessed April 5, 2013]; Available at http://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/products/maxdiff/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Third Edition. London UK: Sage Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latour JM, van Goudoever JB, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. Differences in the perceptions of parents and healthcare professionals on pediatric intensive care practices. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:e211–e215. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181fe3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latour JM, van Goudoever JB, Schuurman BE, et al. A qualitative study exploring the experiences of parents of children admitted to seven Dutch pediatric intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:319–325. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2074-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasper JW, Nyamathi AM. Parents of children in the pediatric intensive care unit: What are their needs? Heart Lung. 1988;17:574–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ames KE, Rennick JE, Baillargeon S. A qualitative interpretive study exploring parents’ perception of the parental role in the paediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2011;27:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meert KL, Eggly S, Pollack M, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network: Parents’ perspectives on physician-parent communication near the time of a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:2–7. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000298644.13882.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renjilian CB, Womer JW, Carroll KW, et al. Parental explicit heuristics in decision-making for children with life-threatening illnesses. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e566–e572. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsiao JL, Evan EE, Zeltzer LK. Parent and child perspectives on physician communication in pediatric palliative care. Palliat Support Care. 2007;5:355–365. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507000557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harbaugh BL, Tomlinson PS, Kirschbaum M. Parents’ perceptions of nurses’ caregiving behaviors in the pediatric intensive care unit. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2004;27:163–178. doi: 10.1080/01460860490497985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson MR, Thiel MM, Backus MM, et al. Matters of spirituality at the end of life in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e719–e729. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meert KL, Thurston CS, Briller SH. The spiritual needs of parents at the time of their child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit and during bereavement: A qualitative study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:420–427. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000163679.87749.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies B, Brenner P, Orloff S, et al. Addressing spirituality in pediatric hospice and palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2002;18:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hexem KR, Mollen CJ, Carroll K, et al. How parents of children receiving pediatric palliative care use religion, spirituality, or life philosophy in tough times. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:39–44. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]