Highlights

-

•

Bowel ischemia and necrosis is an uncommon complication of anorexia nervosa.

-

•

We present a case of a 30 year old woman with long-standing AN complicated by ischemia and necrosis of the entire small bowel and the right hemicolon.

-

•

A high index of suspicion of bowel ischemia is necessary when patients with AN present with abdominal symptoms.

-

•

Timely diagnosis and treatment may prevent bowel necrosis and death.

Abstract

Introduction

Bowel ischemia and necrosis is an uncommon complication of anorexia nervosa (AN), which may pose significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. The review of the existing literature shows that the mortality rate of this condition reaches 80%.

Case

We present a case of a 30 year old woman with long-standing AN complicated by ischemia and necrosis of the entire small bowel and the right hemicolon.

Conclusion

A high index of suspicion of bowel ischemia is necessary when patients with AN present with abdominal symptoms. Timely diagnosis and treatment may prevent bowel necrosis and death.

1. Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is an increasingly common and potentially life-threatening psychiatric disorder with numerous complications from severe weight loss and malnutrition [1], [2], [3]. AN affects predominantly adolescent women with female-to-male ratio 20:1 [4].

Chronic starvation affects all organ systems and causes a myriad of psychological and somatic symptoms. Some complications, including endocrine disbalance, hypothermia, bradycardia, and amenorrhea are pervasive, and may be required to diagnose AN. Other complications are uncommon and may pose significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Bowel ischemia is an uncommon complication of AN, which may lead to bowel infarction (necrosis) and death. Owing to its rarity, the literature on this condition is scant and deals exclusively with case reports. Only 4 cases have been described in the past [5], [6], [7], [8].

We report a case of ischemia and necrosis of the entire small bowel and the right hemicolon and outline possible diagnostic and management options.

2. Case

A 30-year-old woman with long-standing AN and body mass index (BMI) of 11 kg/m2 presented to the emergency department with a several day history of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, an worsening abdominal pain. She had a history of previous hospitalisations for severe weakness and correction of electrolyte disbalance and anemia.

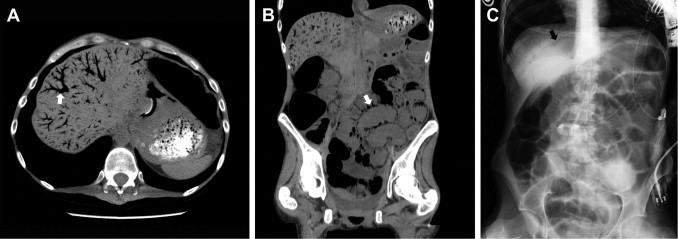

At this admission, she was emaciated and dehydrated with distended abdomen and signs of generalized peritonitis. She was in hypovolemic shock with heart rate of 92/min and blood pressure 70/30 mmHg. She was hypothermic 34.3 °C, tachypneic up to 30/min with oxygen saturation of 98% on 2 L of nasal cannula. Laboratory evaluation revealed metabolic acidosis (pH 7.21, PaCO2 30 mm Hg, base deficit 19 mEq/L) and electrolyte derangement with sodium 116 mmol/L, potassium 3.9 mmol/L, chloride 85 mmol/L, bicarbonate 10 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 94 mg/dL, anion gap 21 mmol/L, and creatinine 3.01 mg/dL. She had microcytic anemia with white blood cell count 14,200/mm3, hemoglobin 10.7 g/dL, hematocrit 31%, mean corpuscular volume 73 fL, and platelets 546,000 /mm3. Abdominal X-ray (AXR) and computer tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1A–C) showed extensive portal venous gas and bowel wall pneumatosis.

Fig. 1.

(A) Axial CT showing extensive portal venous gas (white arrow); (B) coronal CT showing intestinal pneumatosis (white arrow); (C) abdominal X-ray showing portal venous gas (black arrow).

Initial management included aggressive resuscitation with intravenous crystalloids, infusion of sodium bicarbonate, placement of nasogastric tube (NGT) for gastric decompression, broad spectrum systemic antibiotics, and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) for close monitoring.

Despite the intermediate response to continuous fluid boluses in the next three hours, patient’s hemodynamic status remained unstable requiring addition of vasoactive agents to the treatment regimen. At that point, it was felt that patient deterioration secondary to bowel ischemia and uncontrolled sepsis source was unlikely to be reversed with non-operative measures, alone. A detail discussion of potential risks and benefits of operative versus non-operative treatment alternatives was conducted with the patient and patient’s family. The final decision was to take the patient to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy, possible bowel resection, and control of sepsis source. Exploration of the abdomen revealed necrosis of the entire small bowel and the right hemicolon, which was deemed incompatible with survival. Patient expired soon after the surgery.

3. Discussion

Gastrointestinal (GI) complications have been well recognized in patients with AN [9], [10]. Many AN patients (up to 60%) had at some point seen a clinician for GI complaints including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting or bloating. Most of these nonspecific symptoms usually represent some of the frequently seen nonfatal GI complications such as delayed gastric emptying, delayed small bowel transit time or constipation [9]. Therefore, these complaints may be considered more bothersome than dangerous. On the other hand, same symptoms could be the early manifestation of some of the less common, but potentially life-threatening GI complications such as spontaneous rupture of the stomach, pancreatitis or bowel ischemia and necrosis.

Bowel ischemia and necrosis is a rare complication of AN with very few cases described in the literature [5], [6], [7], [8]. All five patients, including our case, were young females with severe weight loss (average BMI 11 ± 1 kg/m2) and worsening AN requiring multiple hospitalizations.

The early presentation and signs including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and bloating were nonspecific and developed insidiously over several days. Therefore, it is hard to argue that distinguishing between possible ischemia and other frequently seen GI complications could be extremely challenging at this early stage. The clinical suspicion of bowel ischemia became much higher when signs of peritonitis, body diarrhea, sepsis and circulatory collapse developed with characteristic radiological features of intestinal pneumatosis and portal venous gas evident on AXR and CT scan. In this regard, it is not surprising that the diagnosis of bowel ischemia was delayed in four out of five patients (80%) with an average time from the onset of GI symptoms to establishing diagnosis and treatment of approximately 3 days (range 1–4). The fifth patient was diagnosed within 12 h of developing GI symptoms while in the hospital for management of worsening nutritional status [7]. Although this patient did not develop peritonitis, she did have the pathognomonic radiographic findings of intestinal pneumatosis and portal venous gas on AXR.

All patients were initially monitored closely and managed by aggressive resuscitation, NGT, intravenous antibiotics, and bowel rest.

All four patients who had late presentation and generalized peritonitis underwent exploratory laparotomy. The patient who had no evidence of peritonitis and was diagnosed within the first 12 h was managed non-operatively.

The pathological intraoperative findings included one case of necrosis of the right hemicolon [6], one case of necrosis of the terminal ileum and cecum [8], and a case of ischemia and necrosis of the entire colon [5]. Our patient had necrosis of the entire small bowel and the right hemicolon. All four patients who underwent laparotomy for generalized peritonitis died. The patient without evidence of peritonitis who was managed non-operatively survived. Overall mortality rate was 80%.

Acute mesenteric ischemia can be due to occlusive or nonocclusive obstruction of arterial or venous blood flow. Occlusive arterial obstruction is most commonly due to emboli or thrombosis of mesenteric arteries, while occlusive venous obstruction is most commonly due to thrombosis or segmental strangulation. Non-occlusive arterial hypoperfusion is most commonly due to splanchnic vasoconstriction secondary to low flow mesenteric circulation. The pathophysiology of bowel ischemia in AN is not completely clarified. However, review of the reported cases showed that all patients seem to develop non-occlusive form of bowel ischemia, most likely related to the numerous medical complications of AN. Among the possible underlying causes are chronic malnutrition followed by electrolyte derangement and major fluid shifts on refeeding, structural cardiovascular abnormalities leading to low flow mesenteric circulation, as well as bowel distension from severe constipation or gastrointestinal paresis.

4. Conclusion

Rapid diagnosis is essential to prevent the catastrophic events associated with intestinal infarction. A high index of suspicion of bowel ischemia is necessary when patients with AN present with abdominal symptoms. As it is implied by the review of the few cases described in the literature, proper and timely diagnosis and treatment of bowel ischemia within the first 24 h of presentation are crucial in preventing bowel necrosis and death.

Conflicts of interest

None

Funding

None

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s guardian for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Vladimir Neychev – contributed for the study design, data collections, data analysis, writing, andreview

John Borruso – contributed for the study design, data analysis, writing, and review

References

- 1.Eagles J.M., Johnston M.I., Hunter D., Lobban M., Millar H.R. Increasing incidence of anorexia nervosa in the female population of northeast scotland. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1995;152(9):1266–1271. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meczekalski B., Podfigurna-Stopa A., Katulski K. Long-term consequences of anorexia nervosa. Maturitas. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McBride O., McManus S., Thompson J., Palmer R.L., Brugha T. Profiling disordered eating patterns and body mass index (BMI) in the english general population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013;48(5):783–793. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0613-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlat D.J., Camargo C.A., Jr., Herzog D.B. Eating disorders in males: a report on 135 patients. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1127–1132. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaye J.C., Madden M.V., Leaper D.J. Anorexia nervosa and necrotizing colitis. Postgrad. Med. J. 1985;61(711):41–42. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.61.711.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakka S., Hurst P., Khawaja H. Anorexia nervosa and necrotizing colitis: case report and review of the literature. Postgrad. Med. J. 1994;70(823):369–370. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.70.823.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diamanti A., Basso M.S., Cecchetti C. Digestive complication in severe malnourished anorexia nervosa patient: a case report of necrotizing colitis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2011;44(1):91–93. doi: 10.1002/eat.20778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamada Y., Nishimura S., Inoue T., Tsujimura T., Fushimi H. Anorexia nervosa with ischemic necrosis of the segmental ileum and cecum. Intern. Med. 2001;40(4):304–307. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell J.E., Crow S. Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2006;19(4):438–443. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000228768.79097.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricanati E.H., Rome E.S. Eating disorders: recognize early to prevent complications. Cleve Clin J. Med. 2005;72(10):895–896. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.72.10.895. 898–900, 902 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]