Abstract

Background:

We aimed to evaluate the effects of Pimpinella anisum (anise) from Apiaceae family on relieving the symptoms of postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) in this double-blind randomized clinical trial.

Materials and Methods:

Totally, 107 patients attending the gastroenterology clinic, aged 18-65 years, diagnosed with PDS according to ROME III criteria and signed a written consent form were enrolled. They were randomized to receive either anise or placebo, blindly, for 4 weeks. Anise group included 47 patients and received anise powders, 3 g after each meal (3 times/day). Control group involved 60 patients and received placebo powders (corn starch), 3 gafter each meal (3 times/day). The severity of Functional dyspepsia (FD) symptoms was assessed by FD severity scale. Assessments were done at baseline and by the end of weeks 2, 4 and 12. Mean scores of severity of FD symptoms and the frequency distribution of patients across the study period were compared.

Results:

The age, sex, body mass index, smoking history, and coffee drinking pattern of the intervention and control groups were not significantly different. Mean (standard deviation) total scores of FD severity scale before intervention in the anise and control groups were 10.6 (4.1) and 10.96 (4.1), respectively (P = 0.6). They were 7.04 (4.1) and 12.30 (4.3) by week 2, respectively (P = 0.0001), 2.44 (4.2) and 13.05 (5.2) by week 4, respectively (P = 0.0001), and 1.08 (3.8) and 13.30 (6.2) by week 12, respectively (P = 0.0001).

Conclusion:

This study showed the effectiveness of anise in relieving the symptoms of postpartum depression. The findings were consistent across the study period at weeks 2, 4 and 12.

Keywords: Anise, functional dyspepsia, Pimpinella anisum, postprandial distress syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a prevalent gastrointestinal (GI) disorder. Its prevalence is different in various populations and outpatient clinics.[1] The patients suffer from dyspepsia, but no pathologic lesion, or metabolic abnormality is identified.[2] They complain about epigastric pain/burning or upper abdomen postprandial discomforts. According to Rome III criteria, FD includes two main subtypes of epigastric pain syndrome and postprandial distress syndrome (PDS).[3,4] The latter involves patients with meal-related symptoms of bothersome postprandial fullness and early satiety. Its etiology is very complex and may include gastric dysmotility (delayed gastric emptying),[5,6,7] Helicobacter pylori infection,[8,9,10,11,12] local inflammations,[2,13,14,15,16,17] abnormal brain-gut interactions,[18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] abnormal acid secretion,[27,28] genetic susceptibility,[29,30,31] imbalanced autonomic nervous system and visceral hypersensitivity.[32,33,34,35,36,37] Although the regular pharmacologic treatments for FD include antacids, kinetic-modifying agents, anti-H. pylori antibiotics, anxiolytics, and antidepressants, their benefits are limited in many cases and remained unsatisfactory.[38,39] That's why the search for optimum treatment is continued, and alternative medicine has gained more and more popularity among the patients and even physicians. It has been estimated by World Health Organization that probably 80% of the population around the world may trust traditional medicine to meet their primary health care needs.[40] Unfortunately, there isn’t enough satisfactory evidence based on randomized clinical trials to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of the majority of herbal medicines. One of the herbs in the latter group used to treat patients in over 4000-year history of Iranian medicine was Pimpinella anisum (Apiaceae).[41] Different therapeutic effects have been reported for anise including antioxidant, antifungal,[42] antimicrobial,[43] analgesic,[44] anticonvulsant[45,46] and antispastic[47] properties. It also has many GI effects. For instance, anise implemented its antiulcer effects by inhibiting gastric mucosal damage.[48] The aromatic effects of anise have been effective in the palliation of nausea.[49] Its laxative property has been effective in the treatment of constipation.[50] The aim of current clinical trial was to assess the effects of anise fruit on patients with PDS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The current study was a double-blind, randomized clinical trial conducted in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IUMS). Patients attending Gastroenterology Clinic of the university hospital from August 2013 to March 2014 were evaluated. Totally, 180 patients were visited and assessed. Those who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and signed a written consent form were enrolled in the study. The research protocol was approved by Ethical Committee. The study was registered in Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (registration number, 2013101214980). Inclusion criteria were age of 18-65 years and diagnosed with PDS according to ROME III criteria. The patients had at least one of the following symptoms occurring several times a week in the past 6 months: The discomfort feeling of postprandial fullness and/or early satiety. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, breastfeeding, peptic ulcer, gastroesophageal reflux disease, dysphagia, celiac, GI surgery, irritable bowel syndrome, abdominal pain, night diarrhea, greasy or black stool, blood in stool, mental retardation, immune system disorders, major depression, bipolar disorder and psychosomatic disorders, severe recent weight loss, cancer, renal disorders, current use of antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers, bismuth, metoclopramide, domperidone, lactulose, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, herbal medicines and drug abuse. Patients who took <80% of administered medication or had drug intolerance were withdrawn from the study.

Subjects and intervention

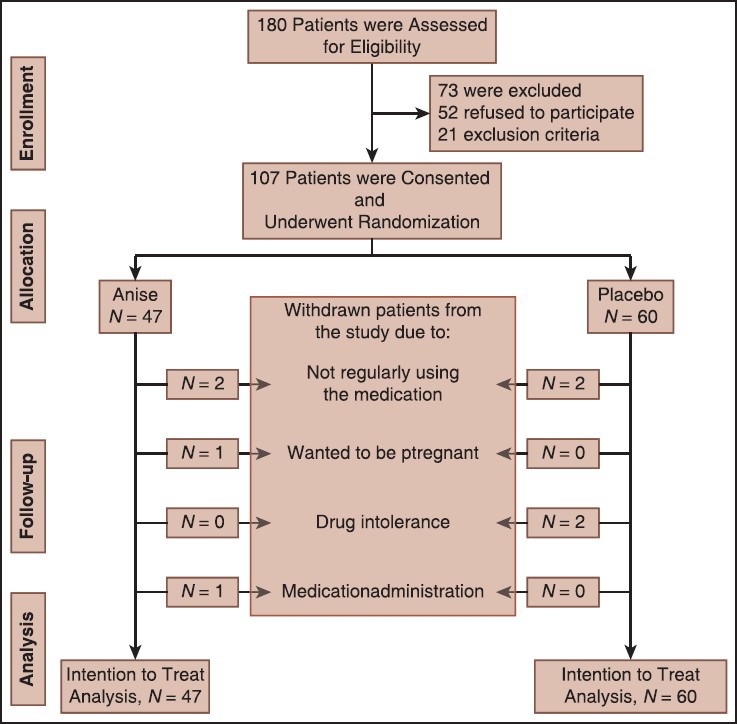

Totally, 107 patients were enrolled in the study [Figure 1]. They were randomized by simple randomization method to blindly receive either anise or placebo for 4 weeks. Intervention group consisted of 47 patients and received anise powder, 3 gafter each meal (3 times/day). According to the Barnes et al.,[51] administration of up to 20 g/day anise powder is safe. The anise seeds were prepared by Barij Essence Pharmaceutical Company (MashhadArdehal, Iran) as a gift. This plant specimen was kept in their herbarium with number 1697.[52] Control group included 60 patients and received placebo powder, 3 g after each meal (3 times/day). The latter included corn starch and were similar to anise package in shape, color, and size. Both powders were prepared in similar packages by Pharmacognosy Department of Isfahan School of Pharmacy at IUMS. One week medications were supplied to the patients at the beginning of the each week for 4 weeks. Both patients and doctors were blind to the treatments.

Figure 1.

Consort flowchart of the study

Instruments and outcomes

To evaluate the presence or absence of symptoms of FD, modified ROME III questionnaire,[3,53] was used. Its validity and reliability have been tested before.[54] The diagnosis of FD was based on the questionnaire filled out individually. To assess the severity of the disorder, FD severity scale was employed.[55] 4-item Likert scale (never or rarely, not very unpleasant, very unpleasant but tolerable, and can’t tolerate) was employed to answer the questions. Each participant's total score was between 0 and 48. A detailed questionnaire was prepared to record the medication side effects too.

All patients were followed-up for 12 weeks. The primary and secondary endpoints were the mean score of severity of FD and the frequency distribution of patients with various severities across the study period, respectively. Assessments were carried out at baseline and at the end of weeks 2, 4 and 12.

Statistical analysis

Intention to treat analysis was used to avoid the bias associated with nonrandom loss of patients. Characteristics of the two groups were compared before and after intervention using Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests for nonparametric variables and Student's t-test for parametric variables. The changes from the baseline to the end of study period within each group were tested using Friedman test and related samples Friedman's two-way analysis of variance by ranks test. P < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), version 17 for Windows was used to conduct statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Totally, 107 patients were enrolled in the study. Totally, 32 (53.3%) and 21 (44.7%) females were included in the control and intervention groups, respectively. The difference was not significant (P = 0.3). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of patients in the control group was 41 (11.7) and in the intervention group was 45.5 (15.5) years (P = 0.1). Totally, 34 (56.7%) and 32 (68%) patients had body mass index ≤25 in the control and intervention groups, respectively (P = 0.4). Totally, 47 (78.3%) patients in the control group and 36 (76.6%) patients in the intervention group never smoked cigarettes (P = 0.9). Totally, 58 (96.7%) and 43 (91%) patients didn’t drink coffee in the control and intervention groups, respectively (P = 0.1). Four patients were withdrawn from the study in each group [Figure 1]. No serious medication side effect was reported in anise group.

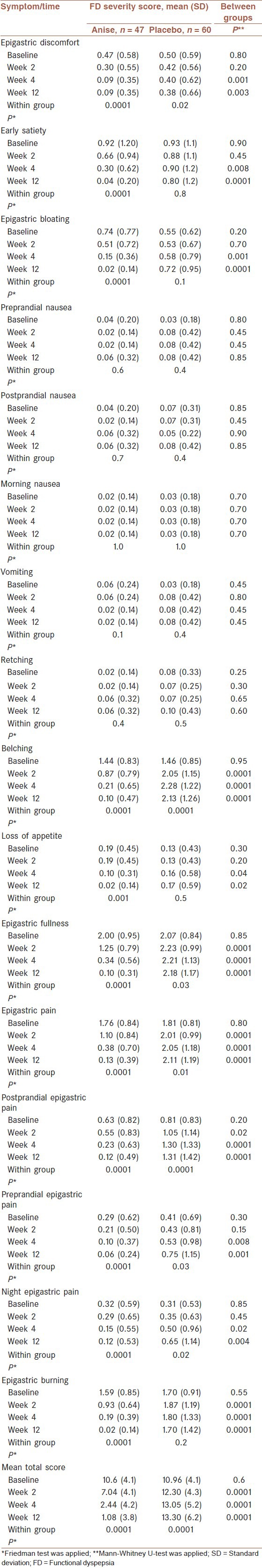

Mean (SD) scores of 16 questions of FD severity scale in the two groups across the study period are shown in Table 1. Among all symptoms, epigastric fullness showed the highest severity and nausea demonstrated the lowest severity in both groups before the intervention [Table 1]. In other words, about 90% of patients had epigastric fullness whereas ≤5% suffered from nausea in both groups at baseline. The baseline mean scores of different FD symptoms were not significantly different between the two groups. After intervention, all symptoms were significantly different between the two groups at weeks 4 and 12, but retching, nausea and vomiting. Similarly, mean total scores of FD severity scale were not significantly different between the two groups before the intervention. But, they were significantly different between the two groups at weeks 2, 4 and 12 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of mean (SD) scores of severity of FD within and between the two groups across the study period

Mean severity scores of epigastric fullness, epigastric discomfort, epigastric burning/pain, early satiety, bloating, belching, and loss of appetite decreased significantly within anise group after intervention whereas only epigastric discomfort showed similar pattern within placebo group. On the other hand, mean severity scores of epigastric pain, epigastric fullness and belching increased significantly within the placebo group after intervention whereas no symptom revealed such an increasing score pattern within anise group [Table 1].

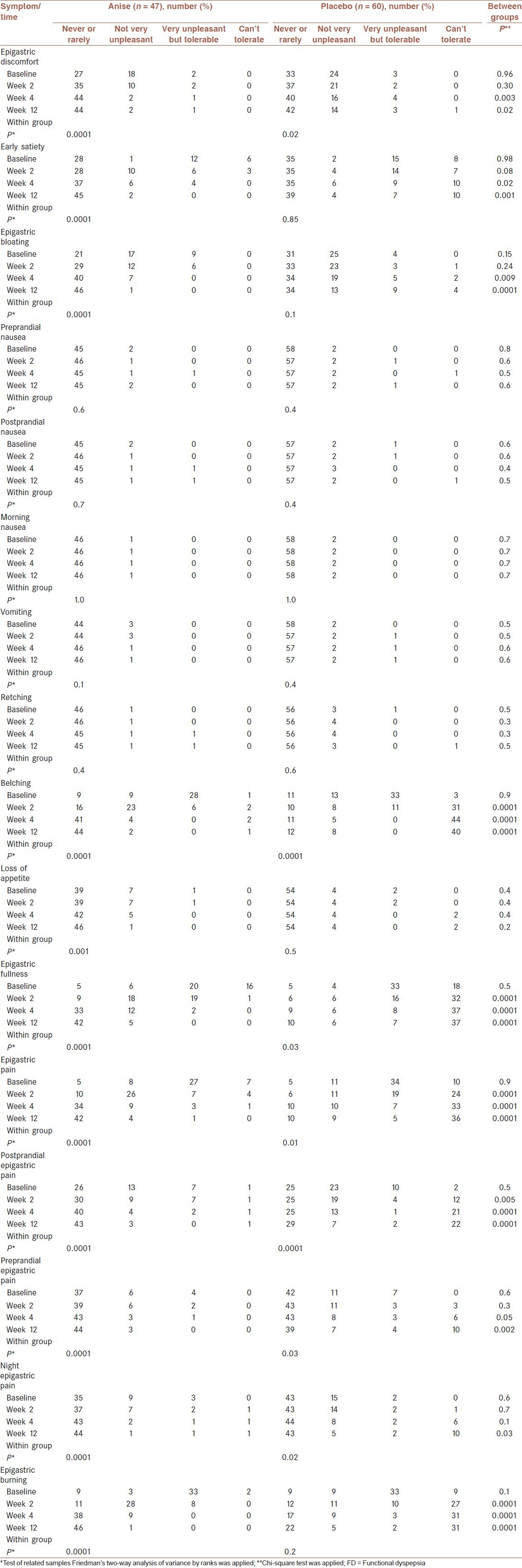

Distributions of the patients in different scales of severity of FD symptoms across the study period are demonstrated in Table 2. Similar to the mean severity scores, the distributions of patients before intervention were not significantly different between the two groups [Table 2]. Furthermore, the patterns of significance and nonsignificance of distributions of patients within each group and between the two groups were similar to those of the severity scores.

Table 2.

Distributions of the patients according to various degrees of severity of FD and comparison of distributions within and between the two groups across the study period

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrated that anise was effective in the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD). Since the pathophysiology of FD is multifactorial and since anise has broad spectrum of pharmacological effects on GI, nervous, muscular and immune systems, it is not a surprise to see significant improvements of symptoms in patients with FD. The spasmolytic feature[50] of anise and its pain relieving character may explain the improvement of postprandial pain and epigastric discomfort. Antimicrobial effects[43] of anise against most bacteria may decrease or inhibit the activities of H. pylori in these patients. Inhibitory effects of anise on gastric mucosal damage[48] may decrease the micro-inflammation of FD. The most important constituents of aniseeds essential oils responsible for the reported effects are trans-anethole, estragole, γ-hymachalen, p-anisaldehyde, and methyl chavicol.[56]

Some other herbs have also been investigated to find out their effectiveness on FD treatment with various results. The most famous ones were Iberogas (a herbal combination preparation, STW 5) which improved the symptoms of FD in 52-68% of cases and peppermint which was effective in 67-97% of patients.[57] Some of them have also been recognized to relieve bloating and intestinal gas. They are called carminatives. Anise, peppermint, and cinnamon are the prototypes of these herbs but few clinical trials have been carried out to show the evidence.[58] This was the first randomized clinical trial assessing the therapeutic effects of anise on patients with FD. But, this study had the following limitations. First, it was conducted in a single center. Thus, the study population was homogenous which limited the external validity of the results. Second, the sample size was small, and the follow-up period was relatively short. It is suggested to include larger numbers of patients with longer periods of follow-up in multiple centers in the future investigations.

CONCLUSIONS

Anise was effective and tolerable in the relieving the symptoms of PPD. These effects were observed even 8 weeks after discontinuation of anise administration.

AUTHOR'S CONTRIBUTION

MM was the principal investigator of the study. MT participated in preparing the design of the study and collecting the data. PA participated in preparing the design of the study, revisited the manuscript and critically evaluated the intellectual contents. AF conducted the analysis of data. AG participated in preparing the final draft of the manuscript, revisited the manuscript and critically evaluated the intellectual contents. MK coordinated in study design and data collection. SAG participated in the preparation of the final draft of the manuscript, revisited the manuscript and critically evaluated the intellectual contents. MB participated in data collection and preparation of the final draft of the manuscript, revisited the manuscript and critically evaluated the intellectual contents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Dr. Maryam Mohammadi Masoodi, who assisted us in the execution of the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chang L, Toner BB, Fukudo S, Guthrie E, Locke GR, Norton NJ, et al. Gender, age, society, culture, and the patient's perspective in the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1435–46. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen MK, Liu SZ, Zhang L. Immunoinflammation and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:225–9. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.98420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: New standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, Spiller R, Talley NJ, Thompson WG. Appendix B: Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2010;75:511–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cogliandro RF, Antonucci A, De Giorgio R, Barbara G, Cremon C, Cogliandro L, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and gut dysmotility in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:1084–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizuta Y, Shikuwa S, Isomoto H, Mishima R, Akazawa Y, Masuda J, et al. Recent insights into digestive motility in functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1025–40. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1966-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorena SL, de Souza Almeida JR, Mesquita MA. Orocecal transit time in patients with functional dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:21–4. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bektas M, Soykan I, Altan M, Alkan M, Ozden A. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on dyspeptic symptoms, acid reflux and quality of life in patients with functional dyspepsia. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:419–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki H, Masaoka T, Sakai G, Ishii H, Hibi T. Improvement of gastrointestinal quality of life scores in cases of Helicobacter pylori-positive functional dyspepsia after successful eradication therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1652–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ladron de GL, Pena-Alfaro NG, Padilla L, Lichtinger A, Figueroa S, Shapiro I, et al. Evaluation of the symptomatology and quality of life in functional dyspepsia before and after Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2004;69:203–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alekseenko SA, Krapivnaia OV, Kamalova OK, Vasiaev VI, Pyrkh AV. Dynamics of clinical symptoms, indices of quality of life, and the state of motor function of the esophagus and rectum in patients with functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Eksp Klin Gastroenterol. 2003;115:54–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su YC, Wang WM, Wang SY, Lu SN, Chen LT, Wu DC, et al. The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and functional dyspepsia in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1900–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer EA, Collins SM. Evolving pathophysiologic models of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:2032–48. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mearin F, Balboa A. Post-infectious functional gastrointestinal disorders: From the acute episode to chronicity. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;34:415–21. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mearin F, Perelló A, Balboa A, Perona M, Sans M, Salas A, et al. Pathogenic mechanisms of postinfectious functional gastrointestinal disorders: Results 3 years after gastroenteritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1173–85. doi: 10.1080/00365520903171276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos J, Alonso C, Guilarte M, Vicario M, Malagelada JR. Targeting mast cells in the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:541–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schurman JV, Singh M, Singh V, Neilan N, Friesen CA. Symptoms and subtypes in pediatric functional dyspepsia: Relation to mucosal inflammation and psychological functioning. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:298–303. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d1363c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou G, Qin W, Zeng F, Liu P, Yang X, von Deneen KM, et al. White-matter microstructural changes in functional dyspepsia: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:260–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koloski NA, Jones M, Kalantar J, Weltman M, Zaguirre J, Talley NJ. The brain - gut pathway in functional gastrointestinal disorders is bidirectional: A 12-year prospective population-based study. Gut. 2012;61:1284–90. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koloski NA, Jones M, Talley NJ. Investigating the directionality of the brain-gut mechanism in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 2012;61:1776–7. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu ML, Liang FR, Zeng F, Tang Y, Lan L, Song WZ. Cortical-limbic regions modulate depression and anxiety factors in functional dyspepsia: A PET-CT study. Ann Nucl Med. 2012;26:35–40. doi: 10.1007/s12149-011-0537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitehouse HJ, Ford AC. Direction of the brain – gut pathway in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 2012;61:1368. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tillisch K, Labus JS. Advances in imaging the brain-gut axis: Functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:407–411.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Böhmelt AH, Nater UM, Franke S, Hellhammer DH, Ehlert U. Basal and stimulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders and healthy controls. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:288–94. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000157064.72831.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobson AR, Aziz Q. Brain imaging and functional gastrointestinal disorders: Has it helped our understanding? Gut. 2004;53:1198–206. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clouse RE. Pharmacotherapy of altered brain-gut interactions in functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25(Suppl 1):S18–9. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199700002-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collingwood S, Witherington J. Therapeutic approaches towards the treatment of gastroinstestinal disorders. Drug News Perspect. 2007;20:139–44. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2007.20.2.1113595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farré R, Tack J. Food and symptom generation in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Physiological aspects. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:698–706. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adam B, Liebregts T, Holtmann G. Mechanisms of disease: Genetics of functional gastrointestinal disorders – searching the genes that matter. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:102–10. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camilleri M, Carlson P, Zinsmeister AR, McKinzie S, Busciglio I, Burton D, et al. Neuropeptide S receptor induces neuropeptide expression and associates with intermediate phenotypes of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:98–107.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holtmann G, Liebregts T, Siffert W. Molecular basis of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:633–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castilloux J, Noble A, Faure C. Is visceral hypersensitivity correlated with symptom severity in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:272–8. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31814b91e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faure C, Giguère L. Functional gastrointestinal disorders and visceral hypersensitivity in children and adolescents suffering from Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1569–74. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faure C, Wieckowska A. Somatic referral of visceral sensations and rectal sensory threshold for pain in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Pediatr. 2007;150:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malagelada JR. Sensation and gas dynamics in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 2002;51(Suppl 1):i72–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.suppl_1.i72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mönnikes H, Tebbe JJ, Hildebrandt M, Arck P, Osmanoglou E, Rose M, et al. Role of stress in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Evidence for stress-induced alterations in gastrointestinal motility and sensitivity. Dig Dis. 2001;19:201–11. doi: 10.1159/000050681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quigley EM. Disturbances of motility and visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome: Biological markers or epiphenomenon. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:221–33. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.010. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zwolinska-Wcislo M, Galicka-Latala D. Epidemiology, classification and management of functional dyspepsia. Przegl Lek. 2008;65:867–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu JC. Psychological co-morbidity in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Epidemiology, mechanisms and management. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:13–8. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. World Health Organization. The World Health Report, Mental Health: New Understanding New Hope. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdollahi Fard M, Shojaii A. Efficacy of Iranian traditional medicine in the treatment of epilepsy. Biomed Res Int 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/692751. 692751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kosalec I, Pepeljnjak S, Kustrak D. Antifungal activity of fluid extract and essential oil from anise fruits (Pimpinella anisum L. Apiaceae) Acta Pharm. 2005;55:377–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaudhry NM, Tariq P. Bactericidal activity of black pepper, bay leaf, aniseed and coriander against oral isolates. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2006;19:214–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tas A. Analgesic effect of Pimpinella anisum L. essential oil extract in mice. Indian Vet J. 2009;86:145–7. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karimzadeh F, Hosseini M, Mangeng D, Alavi H, Hassanzadeh GR, Bayat M, et al. Anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects of Pimpinella anisum in rat brain. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:76. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pourgholami MH, Majzoob S, Javadi M, Kamalinejad M, Fanaee GH, Sayyah M. The fruit essential oil of Pimpinella anisum exerts anticonvulsant effects in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;66:211–5. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tirapelli CR, de Andrade CR, Cassano AO, De Souza FA, Ambrosio SR, da Costa FB, et al. Antispasmodic and relaxant effects of the hidroalcoholic extract of Pimpinella anisum (Apiaceae) on rat anococcygeus smooth muscle. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al Mofleh IA, Alhaider AA, Mossa JS, Al-Soohaibani MO, Rafatullah S. Aqueous suspension of anise “Pimpinella anisum” protects rats against chemically induced gastric ulcers. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1112–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i7.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gilligan NP. The palliation of nausea in hospice and palliative care patients with essential oils of Pimpinella anisum (aniseed), Foeniculum vulgare var. dulce (sweet fennel), Anthemis nobilis (Roman chamomile) and Mentha x piperita (peppermint) Int J Aromather. 2005;15:163–7. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Picon PD, Picon RV, Costa AF, Sander GB, Amaral KM, Aboy AL, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a phytotherapic compound containing Pimpinella anisum, Foeniculum vulgare, Sambucus nigra, and Cassia augustifolia for chronic constipation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barnes J, Anderson LA, Phillipson JD. Herbal Medicine: A Guide for Health Care Professionals. 3rd ed. IL, USA: Pharmaceutical Press; 2007. Aniseed. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kazemi M, Eshraghi A, Yegdaneh A, Ghannadi A. “Clinical pharmacognosy”- A new interesting era of pharmacy in the third millennium. Daru. 2012;20:18. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-20-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1377–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sorouri M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Safaee A, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Pourhoseingholi A, et al. Functional bowel disorders in Iranian population using Rome III criteria. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:154–60. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.65183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adibi P, Keshteli AH, Esmaillzadeh A, Afshar H, Roohafza H, Bagherian-Sararoudi R, et al. The study on the epidemiology of psychological, alimentary health and nutrition (SEPAHAN): Overview of methodology. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17(Spec 2):S291–S297. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shojaii A, Abdollahi Fard M. Review of pharmacological properties and chemical constituents of Pimpinella anisum. ISRN Pharm 2012. 2012 doi: 10.5402/2012/510795. 510795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson Coon J, Ernst E. Systematic review: Herbal medicinal products for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1689–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Low Dog T. A reason to season: The therapeutic benefits of spices and culinary herbs. Explore (NY) 2006;2:446–9. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]