Abstract

Purpose

To determine if day of embryo transfer (ET) affects gestational age (GA) and/or birth weight (BW) at a single university fertility center that primarily performs day 5/6 ET.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of 2392 singleton live births resulting from IVF/ICSI at a single large university fertility center from 2003 to 2012. Patients were stratified by day 3 or day 5/6 ET. Outcome variables included patient age, gravidity, prior miscarriages, prior assisted reproduction technology cycles, number of embryos transferred, number of single ET, infertility diagnosis, neonatal sex, GA at birth, and BW. Subanalyses were performed on subgroups of preterm infants. A comparison was made between the study data and the Society of Assisted Reproductive Technologies (SART) published data.

Results

There was no difference in GA at birth (39 ± 2.1 weeks for day 3 ET, 39 ± 1.9 weeks for day 5/6 ET) or BW between ET groups (3308 ± 568 g for day 3 ET, 3268 ± 543 g for day 5/6 ET). There was also no difference in the number of preterm deliveries (8.5 % for day 3 ET vs. 10.8 % for day 5/6 ET). The day 5/6 ET study data had significantly fewer pre-term deliveries than the SART day 5/6 ET data.

Conclusion

In contrast to published SART data, GA and BW were not influenced by day of ET. Data may be more uniform at a single institution. Day 5/6 ET continues to offer improved pregnancy rates without compromising birth outcomes.

Keywords: Embryo transfer, In vitro fertilization, Preterm birth, Birth weight, Blastocyst

Introduction

In assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles, ET at the blastocyst stage (on day 5/6 of culture) has become increasingly utilized due to several advantages over cleavage stage or day 3 ET. Blastocysts have been found to have higher implantation rates over cleavage stage embryos [1], which may be related to the physiology of the endometrium and the developing embryo. Cleavage stage embryos naturally reside in the oviduct and progress to the blastocyst stage by the time they enter the uterine cavity [2]. The uterine environment, therefore, may be more suited for the blastocyst resulting in improved implantation rates [3, 4]. Higher implantation rates allow for the transfer of fewer embryos with the benefit of decreasing the number of higher order multiple gestations and increasing the success rate of single ET [1, 5, 6]. A recent Cochrane review found that blastocyst ET has a statistically significant higher live birth rate than cleavage stage ET, 32–42 vs 31 % respectively [7]. Furthermore, longer cell culture allows for improved selection of higher grade embryos and decreases the rate of aneuploidy [8–12].

Despite these advantages, a recent analysis of singleton live births from the SART database demonstrated an increased risk of preterm delivery after transfer of blastocyst-stage embryos compared to cleavage-stage embryos (18.6 vs 14.4 % between 32 and 37 weeks gestation and 2.8 vs 2.2 % for less than 32 weeks gestation) [13]. The objective of this study was to determine if the day of ET impacted the gestational age at birth or birth weight of singleton pregnancies at a single large university-based fertility center that primarily performs day 5/6 ETs. We hypothesized that there would be no difference between birth weights and gestational ages at birth between day 3 and day 5/6 ETs given more uniform practices at a large fertility center with experience performing day 5/6 ETs.

Materials and methods

This retrospective cohort study reviewed all singleton live births from 2003 to 2012 resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) and/or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) at the New York University Fertility Center (NYUFC). The exposure group was defined as a singleton live birth following fresh ET on day 5 or 6 after oocyte retrieval and fertilization. The comparison group was defined as a singleton live birth following fresh ET on day 3 after oocyte retrieval and fertilization. The primary outcome variables were gestational age at birth and birth weight. Secondary variables included patient age, gravidity, parity, prior miscarriages, prior ART cycles, number of embryos transferred, number of single ET, infertility diagnosis, and neonatal sex. Exclusion criteria included donor oocyte cycles, frozen oocyte cycles, cycles undergoing pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), multiple gestations, still births or pre-viable births, and singleton live births that were initially multiple gestations (vanishing twins).

Patients underwent stimulation using standard gonadotropin protocols with luteinizing hormone suppression using either a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist or agonist. Ovulation was triggered with human chorionic gonadotropin or GnRH agonist, with oocyte retrieval occurring 35 hours later. Oocytes were fertilized using standard insemination in the majority of cases. ICSI was performed only when indicated (e.g. prior fertilization failure, severe oligospermia, sperm acquired via biopsy, etc.). Embryos were cultured until day 3. If a sufficient number of embryos (generally >3 although criteria varied slightly during the study period) were considered viable at that time, then embryo culture was extended until day 5 or 6.

The statistical analysis of continuous outcome variables was conducted using the t-test with p < 0.05 considered significant. Categorical data were analyzed using Fishers exact test with p < 0.05 considered significant. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov Two-sample test was used to compare the distributions of our two data sets in terms of gestational age at birth and birth weight. Multiple linear regression was performed for gestational age and birth weight in order to adjust for possible confounders. In order to normalize the distributions, gestational age was transformed as –log(323-Gestational Age in days) and birth weight was transformed as –log(7200-birth weight in grams). Multiple linear regression of gestational age was performed considering as independent variables patient age, the diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve, parity, prior ART cycles, prior number of spontaneous losses, the year of the procedure, the day of the embryo transfer, and number of embryos transferred. Multiple linear regression of birth weight was performed considering as independent variables patient age, the diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve, parity, prior ART cycles, prior number of spontaneous losses, the year of the procedure, the day of the embryo transfer, the number of embryos transferred, and the gestational age at birth. Following the multiple regression, gestational age and birth weight could be compared using values adjusted for these possible confounding parameters.

Subanalyses examining groups of preterm infants were performed using Fishers exact test with p < 0.05 considered significant. Subgroups of preterm infants were created based on commonly studied perinatology definitions of preterm infants. Very preterm was defined as <32 weeks gestation, moderately preterm as 32–34 weeks gestation, late preterm as 34–37 weeks gestation, and total preterm as < 37 weeks gestation. A final comparison was made between day 3 and day 5/6 ET data collected at NYUFC and day 3 and day 5/6 ET SART data collected by Kalra et al. [13] using Chi squared with Yate’s correction, p < 0.05 considered significant.

A post-hoc multiple regression power analysis was performed to determine if the study sample size was sufficient to detect a difference in gestational age or birth weight between groups. This study was approved by the institutional review board of New York University School of Medicine.

Results

2392 singleton live births resulting from IVF/ICSI at NYUFC were identified from 2003 to 2012. The 78 patients who underwent ET on days 2, 4, or after day 6 were excluded. Of the remaining 2314 births, 421 underwent day 3 ET and 1893 underwent day 5/6 ET. 14 patients were excluded from the day 3 ET group and 57 patients from the day 5/6 ET group for incomplete birth outcome data. 95 patients in the day 5/6 ET group underwent PGD and were thus excluded. 30 cases of vanishing twins were excluded from the day 3 ET group (30/408, 7.4 %) and 257 cases of vanishing twins were excluded from the day 5/6 ET group (257/1741, 14.8 %). 377 day 3 ETs and 1484 day 5/6 ETs were available for analysis. Table 1 outlines the comparison of primary and secondary outcome variables between exposure and comparison groups. Women undergoing day 3 ET were approximately 2 years older than those undergoing day 5/6 ET. There was no difference in the gravidity, parity, or number of prior miscarriages between groups. Women undergoing day 3 ET were more likely to have had prior ART cycles, more embryos transferred, and fewer single ETs than women undergoing day 5/6 ET. They were also more likely to be undergoing ART due to diminished ovarian reserve.

Table 1.

Results of primary and secondary outcome variables between Day 3 and Day 5/6 ET

| Patients | Day 3 ET (n = 377) | Day 5/6 ET (n = 1484) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 37.9 ± 3.9 | 35.5 ± 4.2 | <0.0001 |

| Gravidity | 1.1 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 1.2 | 0.32 |

| Parity | 0.37 ± 0.6 | 0.34 ± 0.6 | 0.38 |

| Prior Miscarriages | 0.7 ± 1.0 | 0.7 ± 1.0 | 0.54 |

| Prior ART cycles | 1.9 ± 2.0 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| Number Embryos Transferred | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | <0.0001 |

| Single Embryo Transfer | 31 (8.2 %) | 184 (12.4 %) | 0.024 |

| Uterine/Tubal Infertility | 82 (21.8 %) | 308 (20.8 %) | 0.67 |

| Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome | 25 (6.6 %) | 209 (14.1 %) | <0.0001 |

| Endometriosis | 28 (7.4 %) | 104 (7 %) | 0.7375 |

| Diminished Ovarian Reserve | 124 (32.9 %) | 174 (11.7 %) | <0.0001 |

| Male Factor Infertility | 55 (14.6 %) | 269 (18.1 %) | 0.11 |

| Unexplained Infertility | 62 (16.4 %) | 416 (28 %) | <0.0001 |

| Male Sex of Neonate | 188 (49.9 %) | 780 (52.6 %) | 0.3562 |

| Female Sex of Neonate | 189 (50.1 %) | 704 (47.4 %) | 0.3562 |

| Gest Age (wks) | 39.0 ± 2.1 | 39.0 ± 1.9 | 0.93 |

| Gest Age (wks) Adjusted (95%CI)b,c | 39.3 (39.1–39.5) | 39.26 (39.22–39.3) | N/A |

| Birth Weight (gms) | 3308 ± 568 | 3268 ± 543 | 0.22 |

| Birth Weight (gms) Adjusted (95 % CI)b,d | 3324 (3273–3375) | 3311 (3298–3324) | N/A |

a T-test

bAdjusted for patient age, infertility diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve, year of cycle, parity, prior spontaneous abortions, prior ART cycles, number of embryos transferred

cLinear regression of gestational age transformed as –log (323-Gestational Age in days)

dLinear regression of birth weight transformed as –log (7200-birth weight in grams)

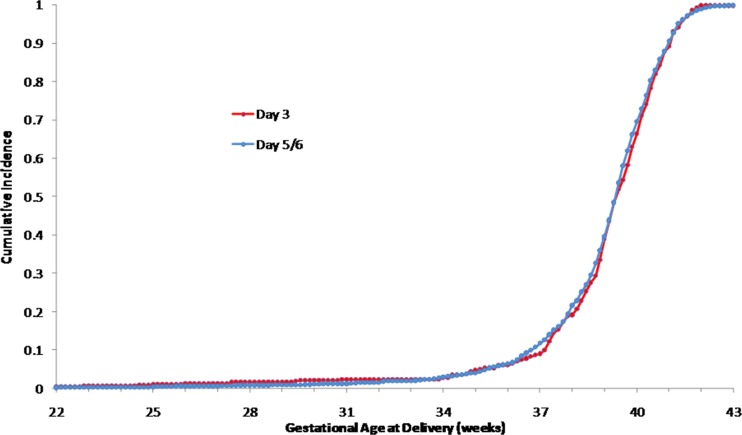

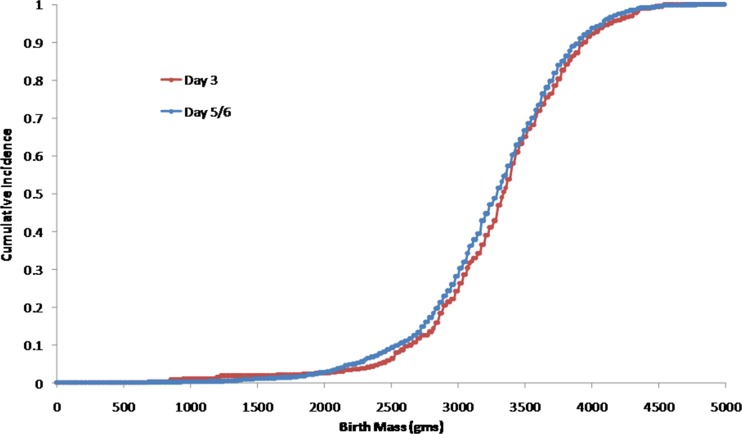

The distributions of the day 3 ET and day 5/6 ET data sets were plotted as cumulative distributions (Figs. 1 and 2) using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test. There was no difference between the distributions of gestational age at birth (Fig. 1, p > 0.999) or the distributions of birth weights for the two study groups (Fig. 2, p > 0.2).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative histograms of gestational age at delivery for Day 3 and Day 5/6 ET (Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test, p > 0.999)

Fig. 2.

Cumulative histograms of birth mass at delivery for Day 3 and Day 5/6 ET (Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test, p > 0.2)

Multiple linear regression of gestational age and birth weight provided adjustments for the possible confounders of patient age, the diagnosis with diminished ovarian reserve, parity, prior ART cycles, prior number of spontaneous losses, the year of the procedure, and the number of embryos transferred. There was no significant association between gestational age and day of ET. Adjusted mean values (95 % confidence limits) of gestational age were 39.3 weeks for day 3 ET (39.1–39.5) and 39.26 weeks for day 5/6 ET (39.22–39.3) (Table 1). Post hoc power was estimated to be >0.99. There was also no significant association between birth weight and day of ET. Adjusted mean values (95 % confidence limits) of birth weight were 3324 g for day 3 ET (3273–3375) and 3311 g for day 5/6 ET (3298–3324) (Table 1). Post hoc power was estimated to be 0.984.

Subanalyses of preterm groups of infants between day 3 and day 5/6 ET were performed (Table 2). The results revealed no statistical difference between ET groups in the number of very preterm, moderate preterm, late preterm, or total preterm births.

Table 2.

Number of patients delivered preterm in Day 3 and Day 5/6 ET groups

| Preterm Groups | Day 3 ET NYUFC (n = 377) | Day 3 ET SARTa

(n = 32351) |

Day 5/6 ET NYUFC (n = 1484) |

Day 5/6 ET SARTa (n = 14743) | NYUFC Day 3 vs Day 5 ET P valueb | NYUFC vs SARTa Day 3 ET P valuec | NYUFC vs SARTa Day 5/6 ET P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <32 weeks | 6 (1.6 %) | 714 (2.2 %) | 12 (0.8 %) | 414 (2.8 %) | 0.23 | 0.53 | <0.0001 |

| 32–34 weeks | 1 (0.3 %) | N/A | 16 (1.1 %) | N/A | 0.22 | N/A | N/A |

| 34–37 weeks | 25 (6.6 %) | N/A | 132 (8.9 %) | N/A | 0.18 | N/A | N/A |

| 32–37 weeks | 26 (6.9 %) | 4645 (14.4 %) | 148 (10 %) | 2743 (18.6 %) | 0.07 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| <37 weeks | 32 (8.5 %) | 5359 (16.6 %) | 160 (10.8 %) | 3170 (21.5 %) | 0.22 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

There was an overall difference in the incidence of preterm deliveries between the NYUFC day 3 ET and day 5/6 ET data compared to the SART data published by Kalra et al. [13] (Table 2). There was a significant difference between the NYUFC day 3 ET data and the SART day 3 ET data in the preterm group between 32 and 37 weeks gestation and for the <37 weeks gestation group. The incidence of premature deliveries in the NYUFC day 5/6 ET data was significantly less than the incidence in the SART data for all preterm groups.

Discussion

In contrast to the SART data published by Kalra et al. [13], we found no overall difference in birth weight or gestational age between day 3 and day 5/6 ET for patients at NYUFC. Comparing day 3 and day 5/6 ET we found no difference in the subgroups of very preterm, moderately preterm, late preterm, and total preterm deliveries. When comparing the distributions of data between day 3 and day 5/6 ET in terms of birth weight or gestational age at birth we also did not find a difference. Furthermore, the incidence of premature delivery among NYUFC patients was significantly less than that observed for the SART data [13] for both day 3 and day 5/6 ET groups.

Data from a single fertility center may be more uniform compared to a nationwide database such as SART that represents a wide range of practices with inherent variations. This may explain why there was a statistically significant difference between the NYUFC day 3 and day 5/6 ET data compared to the SART day 3 and day 5/6 ET data. These differences may be secondary to differences in embryo culture techniques, embryo selection criteria, patient demographics, or regional access to specialists during the antenatal period.

Our data excluded pregnancies with documented vanishing twins. Singleton pregnancies that began as multiple gestations are known to be at increased risk of pre-term birth [14, 15]. There were significantly more vanishing twins among day 5/6 ETs than day 3 ETs (14.8 vs 7.4 %, p < 0.0001). This may be secondary to improved implantation rates with blastocyst transfers [1, 3–5]. The SART data did not exclude vanishing twins; however, the study was able to adjust for reduction in fetal heart tones to diminish this confounder [13]. The possible contribution of vanishing twins to preterm birth with day 5/6 ET should be further investigated. Because day 5/6 ETs may be associated with a higher rate of vanishing twins with a theoretical increased risk of preterm birth, transfer of fewer blastocysts or single ET should be considered with blastocyst transfers.

This study was limited by its retrospective design and possible selection bias. Patients with poor prognostic factors such as age >35yo, fewer embryos available for transfer, or multiple failed IVF cycles were more likely to undergo day 3 ET due to the risk of losing viable embryos in the process of extended embryo culture. These poor prognostic factors in and of themselves may increase the risk of poor birth outcomes such as preterm birth or low birth weight. The study data spans 9 years, and over this time period laboratory techniques, clinical practices, and culture conditions likely changed. Over time, more patients became candidates for day 5/6 ET and a greater proportion of day 5/6 ETs were performed. An attempt to control for these confounders was made by performing a multiple linear regression. When controlling for patient age, diminished ovarian reserve diagnosis, year of cycle, parity, prior spontaneous abortions, prior ART cycles, and number of embryos transferred, transfer day was not significantly associated with gestational age or birth weight. Our study groups were smaller than the published SART data [13]; however, post-hoc power analysis revealed that our study was sufficiently powered to detect a difference in birth weight or gestational age between groups (Gestational Age Power > 0.99, Birth Weight P = 0.984).

Extended embryo culture to the blastocyst stage has emerged as a way to select the single best embryo for transfer. Elective single blastocyst embryo transfer has been shown to have equivalent implantation and pregnancy rates compared to double embryo transfer while significantly reducing the rate of twin gestations [16]. Emerging technology like pre-implantation genetic screening (PGS) is used to select a single euploid embryo for transfer, therefore, improving pregnancy rates and decreasing the miscarriage rate due to aneuploidy [17–20]. PGS relies more on blastocyst-stage biopsies which pose less risk of damage to the embryo and allow for the genetic analysis of a greater number of cells reducing the risk of misdiagnosis secondary to mosaicism [21–24]. With the increasing reliance of blastocyst-stage ET in ART cycles, any adverse perinatal outcomes associated with extended embryo culture needs to be identified.

Our results do not support the national SART trends published by Kalra et al. [13]. Prospective studies are needed to investigate the relationship between day of embryo transfer and birth outcomes. Day 5/6 ETs continue to offer the advantages of enhanced pregnancy rates, improved implantation rates, and decreased risk of multiple gestations with single ET.

Acknowledgments

All NYU Fertility Center physicians, embryologists, nurses, and support staff.

These data were presented at the 61st annual meeting of the Pacific Coast Reproductive Society, April 17–21, 2013, Indian Wells, CA.

Financial support

None

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Capsule

This retrospective cohort study of singleton live births resulting from IVF/ICSI at the New York University Fertility Center found no difference in birth outcomes between day 3 and day 5/6 embryo transfers.

References

- 1.Blake DA, Farquhau CM, Johnson N, Proctor M. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stage embryo transfer in assisted conception. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4, Art. No.: CD002118. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002118.pub3.

- 2.Croxatto HB, Ortiz ME, Diaz S, et al. Studies on the duration of egg transport by the human oviduct. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978;132:629–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(78)90854-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bavister BD. Culture of preimplantation embryos: facts and artifacts. Hum Reprod Update. 1995;1:91–148. doi: 10.1093/humupd/1.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner DK, Lane M, Calderon I, Leeton J. Environment of the pre-implantation human embryo in vivo: metabolite analysis of oviduct and uterine fluids and metabolism of cumulus cells. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:349–353. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner DK, Vella P, Lane M, Wagley L, Schlenker T, Schoolcraft WB. Culture and transfer of human blastocysts increases implantation rates and reduces the need for multiple embryo transfers. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:84–8. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)00438-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grifo JA, Flisser E, Adler A, McCaffrey C, Krey LC, Licciardi F, et al. Programmatic implementation of blastocyst transfer in a university-based in vitro fertilization clinic: maximizing pregnancy rates and minimizing triplet rates. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glujovsky D, Blake D, Bardach A, Farquhar C. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 7, Art. No.:CD002118. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002118.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ata B, Kaplan B, Danzer H, Glassner M, Opsahl M, Tan SL, et al. Array CGH analysis shows that aneuploidy is not related with the number of embryos generated. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;24:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munné S, Alikani M, Tomkin G, Grifo J, Cohen J. Embryo morphology, developmental rates, and maternal age are correlated with chromosome abnormalities. Fertil Steril. 1995;64(2):382–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staessen C, Platteau P, Van Assche E, et al. Comparison of blastocyst transfer with or without preimplantation genetic diagnosis for aneuploidy screening in couples with advance maternal age: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Human Reprod. 2004;19:2849–58. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler A, Lee HL, McCulloh DH, Ampeloquio E, Clarke-Williams M, Hodes-Wertz B, et al. Blasotcyst culture selects for euploid embryos: comparison of blastomere biopsy and trophectoderm biopsy. Reprod BioMed Online. 2013;28(4):485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harton GL, Munne S, Surrey M, Grifo J, Kaplan B, McCulloh DH, et al. Diminished effect of maternal age on implantation after preimplantation genetic diagnosis with array comparative genomic hybridization. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(6):1695–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalra SK, Ratcliffe SJ, Barnhart KT, Coutifaris C. Extended embryo culture and an increased risk of preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:69–75. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31825b88fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinborg A, Lidegaard O, la Cour Freiesleben N, Andersen AN. Consequences of vanishing twins in IVF/ICSI pregnancies. Human Reprod. 2005;20(10):2821–29. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickey RP, Taylor SN, Lu PY, Sartor BM, Storment JM, Rye PH, et al. Spontaneous reduction of multiple pregnancy: incidence and effect on outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:77–83. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.118915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Criniti A, Thyer A, Chow G, Lin P, Klein N, Soules M. Elective single blastocyst transfer reduces twin rates without compromising pregnancy rates. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grifo JA, Hodes-Wertz B, Lee HL, Amperloquio E, Clarke-Williams M, Adler A. Single thawed euploid embryo transfer improves IVF pregnancy, miscarriage, and multiple gestation outcomes and has similar implantation rates as egg donation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30(2):259–264. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9929-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoolcraft WB, Fragouli E, Stevens J, Munné S, Katz-Jaffe MG, Wells D. Clinical application of comprehensive chromosomal screening at the blastocyst stage. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1700–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott RT, Ferry K, Su J, Tao X, Scott K, Treff NR. Comprehensive chromosome screening is highly predictive of the reproductive potential of human embryos: a prospective, blinded, nonselection study. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:870–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Z, Liu J, Collins GS, Salem SA, Liu X, Lyle SS, et al. Selection of single blastocysts for fresh transfer via standard morphology assessment alone and with array CGH for good prognosis IVF patients: results from a randomized pilot study. Mol Cytogenet. 2012;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capalbo A, Wright G, Themaat L, Elliott T, Rienzi L, Nagy ZP. Fish reanalysis of inner cell mass and trophectoderm samples of previously array-CGH screened blastocysts reveals high accuracy of diagnosis and no sign of mosaicism or preferential allocation. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:S22. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mottla GL, Adelman MR, Hall JL, Gindoff PR, Stillman RJ, Johnson KE. Liineage tracing demonstrates that blastomeres of early cleavage-stage human pre-embryos contribute to both trophectoderm and inner cell mass. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:384–91. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Northrop LE, Treff NR, Levy B, Scott RT. SNP microarray-based 24 chromosome aneuploidy screening demonstrates that cleavage-stage FISH poorly predicts aneuploidy in embryos that develop to morphologically normal blastocysts. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16:590–600. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanneste E, Voet T, le Caignec C, Ampe M, Konings P, Melotte C, et al. Chromosome instability is common in human cleavage-stage embryos. Nat Med. 2009;15:577–83. doi: 10.1038/nm.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]