Abstract

Background and Objective:

Ambulatory total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) could lead to significant cost savings, but some fear the effects of what could be premature postsurgical discharge. We sought to estimate the feasibility and safety of TLH as an outpatient procedure for benign gynecologic conditions.

Methods:

We report a prospective, consecutive case series of 128 outpatient TLHs performed for benign gynecologic conditions in a tertiary care center.

Results:

Of the 295 women scheduled for a TLH, 151 (51%) were attempted as an outpatient procedure. A total of 128 women (85%) were actually discharged home the day of their surgery. The most common reasons for admission the same day were urinary retention (19%) and nausea (15%). Indications for hysterectomy were mainly leiomyomas (62%), menorrhagia (24%), and pelvic pain (9%). Endometriosis and adhesions were found in 23% and 25% of the cases, respectively. Mean estimated blood loss was 56 mL and mean uterus weight was 215 g, with the heaviest uterus weighing 841 g. Unplanned consultation and readmission were infrequent, occurring in 3.1% and 0.8% of cases, respectively, in the first 72 hours. At 3 months, unplanned consultation, complication, and readmission had occurred in a similar proportion of inpatient and outpatient TLHs (17.2%, 12.5%, and 4.7% versus 18.1%, 12.7%, and 5.4%, respectively). In a logistic regression model, uterus weight, presence of adhesions or endometriosis, and duration of the operation were not associated with adverse outcomes.

Conclusion:

Same-day discharge is a feasible and safe option for carefully selected patients who undergo an uncomplicated TLH, even in the presence of leiomyomas, severe adhesions, or endometriosis.

Keywords: Ambulatory surgical procedure, Feasibility study, Hysterectomy, Laparoscopy, Safety

INTRODUCTION

Advances in surgery and anaesthesia have allowed hysterectomy to be performed in an ever less invasive manner. Formerly, hysterectomies that could not be completed vaginally were performed by laparotomy. More recently, laparoscopy has become an alternative for a challenging uterus and has shown several advantages over laparotomy, including fewer infections, less postoperative pain, and faster recovery time.1 Laparoscopy is also associated with a shorter hospital stay,1 to a point where hysterectomy can now be an outpatient procedure.2

Although ambulatory hysterectomies could lead to significant cost savings, some experts fear the effects of what could be premature postsurgical discharge. Decreased length of stay has been associated with increased readmission rates after procedures such as cholecystectomy and vaginal delivery.3 However, it has been suggested that proper selection of candidates could help ensure a safe same-day discharge.4

A few case series of outpatient laparoscopic hysterectomies, mostly subtotal, have been published supporting it is a safe practice.2,5–12 However, it is important to distinguish outpatient total laparoscopic hysterectomies (TLHs) from subtotal procedures, given that the former represents a greater challenge for outpatient surgery because of its association with longer operative time and increased morbidity.1

The objective of this study was to estimate the feasibility and safety of TLH as an outpatient procedure for benign gynecologic conditions. We looked at the proportion of TLHs attempted and performed as outpatient procedures and the frequency of unplanned postoperative readmission, consultation, and complication up to 3 months. As a secondary outcome, we looked at the predictors of adverse outcomes.

METHODS

We report a consecutive case series of TLHs performed from January 1, 2010, through July 31, 2013, in a tertiary hospital center by 2 gynecologists with 6 and 22 years in practice. All women scheduled for TLH were prospectively identified for further chart review of medical records, to assess eligibility and perform data abstraction. We included all patients who underwent TLH and were discharged home before midnight on the same day. We excluded subtotal and laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomies and operations performed for malignant disease, as they are associated with different risk and morbidity profiles.1

The women were routinely offered outpatient TLH as long as they met the following preoperative selection criteria:

Adequate motivation and understanding.

Age <60 years.

ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) class 1 or 2, with no sleep apnea.

Presumed benign disease.

No anticipated surgical complications.

Convalescence at a location less than 1 hour from the hospital.

Continuous home support for the first 2 days.

The operations were performed in patients under general anesthesia, with a traditional 4-port laparoscopic technique (port size range, 5–11 mm). No single-port or robot-assisted surgeries were performed. Residents and fellows routinely participated in most cases. A harmonic scalpel (Harmonic Ace; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, Ohio; or Sonicision, Mansfield, Massachusetts) was used in all procedures. Morcellation, when needed, was performed laparoscopically with a power morcellator or vaginally with a cold knife. Either an intracorporeal or extracorporeal knot-tying technique was used to achieve laparoscopic closure of the vaginal vault. A Cohen cannula and a tenaculum were used for uterine manipulation, and an endotracheal tube, inserted into the vagina, ensured further maintenance of pneumoperitoneum. Cystoscopy was routinely performed in all cases, to assess the ureteral jets and bladder integrity. In the absence of contraindication, preoperative medication included acetaminophen, an anti-inflammatory drug, dexamethasone, a 5-HT3 antagonist, a first-generation cephalosporin, and low-dose heparin. Also, port sites were routinely injected with bupivacaine hydrochloride before incision. Given the growing evidence that prophylactic salpingectomy reduces the risk of ovarian cancer13 without increasing morbidity,14 bilateral salpingectomy was progressively offered to most of the patients during the course of the study.

After surgery, a hemoglobin assay was performed approximately 6 hours after the operation. The women had to meet the following discharge criteria; otherwise, they were admitted:

Surgery performed without complication.

- Minimal postoperative observation of 6 hours, after which the patient:

- had adequate pain control,

- tolerated oral liquids without significant nausea,

- could ambulate with support,

- were able to void spontaneously,

- had a soft abdomen and unremarkable wounds, and

- showed a decrease in hemoglobin of less than 20 g/L.

Discharge medications included acetaminophen, an anti-inflammatory drug, and a narcotic, if not contraindicated. The women were given an appointment 8 weeks after the operation. They were asked to refrain from intercourse for 8 weeks and informed of the warning signs that should prompt them to ask for a physician's advice or a consultation at the emergency department. These recommendations were also detailed in a handout. A nurse contacted each woman by phone on postoperative day 1 to conduct a postoperative interview. A verbal report was made to the surgeon when necessary.

Medical records of all the women scheduled for TLH were reviewed. We looked at unplanned admissions, clinic and emergency department visits, and complications during the first 3 postoperative months. We also recorded pre- and perioperative characteristics. Operative time was defined as the period from incision to complete closure, excluding room and anaesthesia time. Blood loss was estimated by suction container contents with irrigation fluid subtracted. The data from medical records were collected by 2 of the authors.

All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Means (±SD), frequencies (%), and range were used to describe population characteristics and outcomes. Missing data and aberrations were investigated and corrected. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine predictors of adverse outcomes, defined as an unplanned admission, consultation, or complication within 3 months. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Key descriptive statistics for inpatient TLHs were provided for guidance. No statistical test was performed to compare outpatient and inpatient TLH, given that the groups were intentionally noncomparable, due to the strict selection criteria for the outpatient candidates. The research ethics committee of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) de Québec approved the study protocol (C11-11-128).

RESULTS

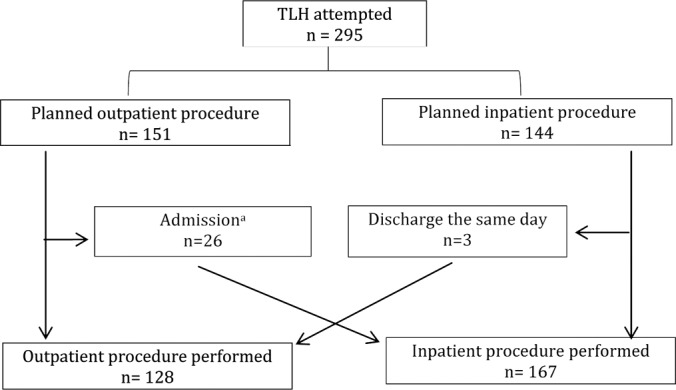

Two hundred ninety-five consecutive TLHs were performed during the study period (Figure 1). One hundred fifty-one (51%) were scheduled as outpatient surgeries and 128 (43%) were actually discharged the same day. The annual proportion of ambulatory TLHs increased from 23% (18/78) to 62% (47/76) during the study period.

Figure 1.

Distribution of total laparoscopic hysterectomies according to the admission status. aReasons for admission: urinary retention (n = 5), nausea (n = 4), hemoglobin decrease ≥20 g/L (n = 3), pain (n = 2), drowsiness (n = 2), stage IV endometriosis requiring extensive dissection (n = 2), conversion to laparotomy because of severe adhesions (n = 2), hematoma of the abdominal wall (n = 2), surgery ending late (n = 1), perioperative bladder trauma (n = 1), perioperative hypertension (n = 1), and upper limb numbness (n = 1).

Of the planned outpatient TLHs (n = 151), admission the day of the surgery occurred in 17%. The most common reasons for admission were urinary retention (19%), nausea (15%), and a decrease in hemoglobin of more than 20 g/L (12%). In the last year of the study, the proportion of unplanned admissions the day of the surgery decreased to 13% of cases.

The characteristics of the women who underwent outpatient TLH are presented in Table 1. Their average age and weight were 45 years and 68 kg, respectively. Most were nonsmokers (80%) and parous (72%). More than half (54%) had undergone 1 or more abdominal operations. The main indications for hysterectomy were leiomyomas (62%), menorrhagia (24%), and pelvic pain (9%). The perioperative characteristics are presented in Table 2. The mean estimated blood loss was 56 mL, with an average decline in hemoglobin of 9 g/L. Endometriosis and adhesions were found in 23% and 25% of cases, respectively, and 41% of the women underwent concomitant oophorectomy. The procedure lasted 131 minutes, on average, and the mean uterus weight was 215 g, the heaviest being 841 g.

Table 1.

Preoperative Characteristics

| Variable | Mean ± SD (range) |

|---|---|

| or n (%) | |

| Mean age, y | 45 ± 5 (34–59) |

| Mean weight, kg | 68 ± 15 (40–149) |

| Parous | 92 (72) |

| Smoker | 26 (20) |

| Comorbiditiesa | 32 (25) |

| Previous abdominal operationsb | |

| None | 59 (46) |

| 1 | 47 (37) |

| 2 | 15 (12) |

| 3+ | 7 (5) |

| Hysterectomy indication | |

| Leiomyomas | 79 (62) |

| Menorrhagia | 31 (24) |

| Pelvic pain | 11 (9) |

| Other | 7 (5) |

n = 128.

Including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.

Including laparoscopy and laparotomy.

Table 2.

Perioperative Characteristics

| Variable | Mean ± SD (range) |

|---|---|

| or n (%) | |

| Estimated blood loss, mL | 56 ± 84 (5–350) |

| Postoperative haemoglobin, g/L | 124 ± 11 (84–145) |

| Variation in hemoglobin, g/L | 9 ± 8 (−36–6) |

| Endometriosis | 30 (23) |

| Adhesions | 32 (25) |

| Oophorectomy | 53 (41) |

| Duration of surgery, min | 131 ±35 (67–221) |

| Uterus weight, g | 215 ±157 (49–841) |

n = 128.

In the first 72 hours after the procedure, 4 women (3.1%) returned to the emergency department for consultation (Table 3). Of them, only 1 was readmitted, with unexplained hyperthermia. During the 3-month postoperative period, 17% of the women consulted either at the emergency department or at the clinic outside of their usual postoperative appointment. Complications, most of them minor, occurred in 10% of cases. In 6 patients (4.7%), the complications were serious enough to warrant readmission. There were 2 cases of vaginal cuff dehiscence (1.6%): 1 was partial and 1 complete. Unplanned consultations, complications, and readmission occurred in similar proportion among the women who underwent inpatient TLH (18.1%, 12.7%, and 5.4%, respectively). No factor, including uterus weight, presence of adhesions or endometriosis, and operative duration, was significantly associated with adverse outcomes in logistic regression analyses.

Table 3.

Readmission, Consultation, and Complication Rates During the 3-Month Follow-up

| Variable | n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 72 Hours | 3 Months | |

| Consultation | 4 (3.1)a | 22 (17.2)b |

| Emergency room | 4 (3.1) | 16 (12.5) |

| Clinic | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.7) |

| Postoperative complication | 2 (1.6) | 13 (10.2) |

| Readmission | 1 (0.8) | 6 (4.7) |

Pain (n = 2), cystitis (n = 1), and unexplained hyperthermia (n = 1*).

Pain (n = 3), normal vaginal discharge (n = 3), constipation (n = 2), cystitis (n = 2), gastritis (n = 2), dysuria without infection (n = 1), vaginal cuff hematoma (n = 1), wound infection (n = 1), infectious enteritis (n = 1), unexplained hyperthermia (n = 1*), complete vaginal cuff dehiscence (n = 1*), partial vaginal cuff dehiscence (n = 1*), vaginal cuff abscess (n = 1*), appendicitis (n = 1*), and pulmonary embolism (n = 1*). *Patient admitted.

DISCUSSION

This study describes a series of outpatient TLHs performed for benign gynecologic conditions. We observed that TLH is feasible in an outpatient context. In fact, in our study, 51% of women who were scheduled for TLH were eligible and agreed to an outpatient procedure. Overall, 43% of the women who underwent TLH were discharged the day of the surgery, a proportion that increased throughout the study period, to 62% in the final year. This proportion is smaller than the one reported for laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy, the latter being as much as 90% to 93%.8,10,11 However, it is larger than the 34% reported for TLH,11 suggesting that advances in technology and the increasing experience of gynecologists will continue to expand the proportion of TLHs performed in a ambulatory setting.

Although outpatient TLH can be planned in a large number of women, some of them will have to be admitted after the operation. During the last year of this study, the proportion corresponded to 13% of cases. The 2 most common reasons were urinary retention and nausea. The key to minimizing admissions is most likely the optimal use of pain and nausea prophylaxis. In addition to medication, simple techniques, such as reduction of the pneumoperitoneum in the Trendelenburg position with manual inflation of the lungs15 and having the patient chew gum,16 were shown to be effective in decreasing postoperative pain and nausea. Moreover, to avoid admission in cases of urinary retention, some centers have established protocols to enable discharge with a Foley catheter or intermittent self-catheterization.11

We established clear pre- and postoperative criteria to select appropriate candidates who could safely undergo outpatient TLH. The operations had to be uncomplicated; however, there was no limitation in uterus weight or the duration and complexity of the surgery. In a logistic regression analysis, we did not find those factors to be associated with adverse outcomes. In the literature, a heavy uterus (>500 g) was not associated with increased morbidity5 or a higher readmission rate11 after laparoscopic hysterectomy. In our study, the heaviest uterus in an outpatient TLH was 841 g. Patients were discharged home the same day, despite the presence of leiomyomas, adhesions, and endometriosis in 62%, 25%, and 23% of cases, respectively. In fact, the outpatient setting is now used for hysterectomies that are increasingly challenging. A recent case series reported its use in laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for severe endometriosis.17

In a reassuring finding, we observed very few emergency department visits and readmissions in the first 72 hours after the operation. Unplanned consultations occurred in 3% of cases, compared to the 6% reported by Perron-Burdick et al.11 We also observed a readmission rate of 0.7% at 72 hours, which is similar to the rate reported by the same authors11 for TLH (0.4%) and subtotal hysterectomy (0.7%). Finally, unplanned consultation, complication, and readmission at 3 months occurred in proportions that are consistent with the range observed in the literature for total and subtotal hysterectomies.8,12,18,19 Most important, proportions were similar to those observed for TLH with postoperative admission to our center.

The surgical technique for TLH is constantly changing, to improve efficiency and patient safety. The practice of morcellation has recently raised concerns about the potential for dissemination of undetected malignant disease.20 At present, the risk is difficult to define, but it should be included in the informed consent.20 Laparoscopy-assisted minilaparotomy, tissue removal through a vaginal incision, and manual morcellation within an endoscopic bag have been proposed as alternatives, but the risks and benefits of such techniques have still to be clarified.20,21 By increasing the technical difficulty of the procedure, we have to make sure that women are not exposed to a higher risk of complication than that of dissemination of an occult cancer. Finally, the increased operative time and morbidity (eg, minilaparotomy) of those techniques could undermine the success of outpatient operations.

In our center, we opt for the routine use of cystoscopy for early detection of urinary tract injury. However, this practice has been debated, given the low incidence of such injuries and the potential disadvantages of cystoscopy, including increased operative time, procedure cost, and incidence of complications, such as bladder trauma, urinary tract infection, and reactions related to the intravenous dye.22 Nevertheless, selective use of cystoscopy in more complex cases or when the integrity of the ureters or bladder is of concern seems reasonable.

This study was observational and clearly differentiated TLH from other types of laparoscopic hysterectomies. We defined outpatient as discharge home before midnight the day of the surgery rather than a stay of less than 24 hours. The latter definition would have led to a greater proportion of outpatient procedures, but we found it important to limit them to cases where no overnight stay was necessary, representing a real reduction in hospital costs. The study was not designed to compare outpatient and inpatient procedures but to describe outcomes of outpatient TLH. Our logistic regression analysis could have been limited by the rarity of adverse outcomes. Complications may have been underestimated if patients presented to outside institutions for treatment. However, these complications could then be documented at the routine postoperative visit scheduled at our center. Finally, some studies have reported a high satisfaction rate with outpatient laparoscopic hysterectomies (≥90%).6,7,12 Patient satisfaction should be assessed in further studies, as it is an important consideration.

CONCLUSION

Same-day discharge is a feasible and safe option for carefully selected patients who undergo uncomplicated TLH. It can be performed in a large proportion of women, even in the presence of leiomyomas, severe adhesions, or endometriosis. Continuing growth in the number of outpatient TLHs is certain to lead to the positive financial impact of substantially decreased hospital costs.

Contributor Information

Sarah Maheux-Lacroix, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Université Laval, Québec City, Québec, Canada.; Center Hospitalier de Québec Research Center, Québec City, Québec, Canada.

Madeleine Lemyre, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Université Laval, Québec City, Québec, Canada.; Center Hospitalier de Québec Research Center, Québec City, Québec, Canada.

Vanessa Couture, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Université Laval, Québec City, Québec, Canada..

Gabrielle Bernier, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Université Laval, Québec City, Québec, Canada..

Philippe Y. Laberge, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Université Laval, Québec City, Québec, Canada.; Center Hospitalier de Québec Research Center, Québec City, Québec, Canada.

References:

- 1. Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD003677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schiavone MB, Herzog TJ, Ananth CV, et al. Feasibility and economic impact of same-day discharge for women who undergo laparoscopic hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:382.e1–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bahrami S, Holstein J, Chatellier G, Le Roux YE, Dormont B. Using administrative data to assess the impact of length of stay on readmissions: study of two procedures in surgery and obstetrics [in French]. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2008;56:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gien LT, Kupets R, Covens A. Feasibility of same-day discharge after laparoscopic surgery in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alperin M, Kivnick S, Poon KY. Outpatient laparoscopic hysterectomy for large uteri. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:689–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Lapasse C, Rabischong B, Bolandard F, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy and early discharge: satisfaction and feasibility study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lassen PD, Moeller-Larsen H, DE Nully P. Same-day discharge after laparoscopic hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91:1339–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lieng M, Istre O, Langebrekke A, Jungersen M, Busund B. Outpatient laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy with assistance of the lap loop. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McClellan SN, Hamilton B, Rettenmaier MA, et al. Individual physician experience with laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy in a single outpatient setting. Surg Innov. 2007;14:102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morrison JE, Jr, Jacobs VR. Outpatient laparoscopic hysterectomy in a rural ambulatory surgery center. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perron-Burdick M, Yamamoto M, Zaritsky E. Same-day discharge after laparoscopic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1136–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thiel J, Gamelin A. Outpatient total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:481–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dietl J, Wischhusen J, Hausler SF. The post-reproductive fallopian tube: better removed? Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2918–2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vorwergk J, Radosa MP, Nicolaus K, et al. Prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy (pbs) to reduce ovarian cancer risk incorporated in standard premenopausal hysterectomy: complications and re-operation rate. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:859–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Phelps P, Cakmakkaya OS, Apfel CC, Radke OC. A simple clinical maneuver to reduce laparoscopy-induced shoulder pain: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1155–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Husslein H, Franz M, Gutschi M, Worda C, Polterauer S, Leipold H. Postoperative gum chewing after gynecologic laparoscopic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nezhat C, Xie J, Aldape D, Balassiano E, Soliemannjad RR, Nezhat F. Use of laparoscopic modified nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for the treatment of extensive endometriosis. Cureus. 2014;6:e159. [Google Scholar]

- 18. David-Montefiore E, Rouzier R, Chapron C, Darai E. Surgical routes and complications of hysterectomy for benign disorders: a prospective observational study in French university hospitals. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoffman CP, Kennedy J, Borschel L, Burchette R, Kidd A. Laparoscopic hysterectomy: the Kaiser Permanente San Diego experience. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kho KA, Nezhat CH. Evaluating the risks of electric uterine morcellation. JAMA. 2014;311:905–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kho KA, Shin JH, Nezhat C. Vaginal extraction of large uteri with the Alexis retractor. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:616–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sandberg EM, Cohen SL, Hurwit S, Einarsson JI. Utility of cystoscopy during hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1363–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]