Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder associated with progressive memory loss and neuronal cell death. Although numerous previous studies have been focused on disease progression or reverse pathological symptoms, therapeutic strategies for AD are limited. Alternatively, the identification of traditional herbal medicines or their active compounds has received much attention. The aims of the present study were to characterize the ameliorating effects of spinosin, a C-glucosylflavone isolated from Zizyphus jujuba var. spinosa, on memory impairment or the pathological changes induced through amyloid-β1–42 oligomer (AβO) in mice. Memory impairment was induced by intracerebroventricular injection of AβO (50 μM) and spinosin (5, 10, and 20 mg/kg) was administered for 7 days. In the behavioral tasks, the subchronic administration of spinosin (20 mg/kg, p.o.) significantly ameliorated AβO-induced cognitive impairment in the passive avoidance task or the Y-maze task. To identify the effects of spinosin on the pathological changes induced through AβO, immunohistochemistry and Western blot analyses were performed. Spinosin treatment also reduced the number of activated microglia and astrocytes observed after AβO injection. In addition, spinosin rescued the AβO-induced decrease in choline acetyltransferase expression levels. These results suggest that spinosin ameliorated memory impairment induced through AβO, and these effects were regulated, in part, through neuroprotective activity via the anti-inflammatory effects of spinosin. Therefore, spinosin might be a useful agent against the amyloid b protein-induced cognitive dysfunction observed in AD patients.

Keywords: Spinosin, Amyloid-β oligomer, Alzheimer’s disease, Neuroprotection

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), an insidious neurodegenerative disorder and the leading cause of dementia, induces the deterioration of memory, the reduction in cognitive function, and several neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with memory loss and neuronal cell death in the elderly (Hendrie, 1997; Koo et al., 1999; Cummings, 2004). The cholinergic hypothesis of AD suggests that the downregulation of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) induces the presynaptic cholinergic deficits observed in the brains of AD patients (Coyle et al., 1983; Francis et al., 1999). At the molecular and cellular levels, AD is characterized by the accumulation of abnormally aggregated proteins such as senile plaques, which primarily comprise insoluble β-amyloid (Aβ) protein, and neurofibrillary tangles of tau protein (Hardy and Allsop, 1991; Lublin and Link, 2013). Although previous studies have been focused on unveiling AD pathology and reducing the symptoms of this disease by clearing Aβ protein, this methodology has been unsuccessful (Yoon and Jo, 2012; Chiang and Koo, 2014). However, neuroinflammation in the central nervous system (CNS) is a central event in the pathophysiology of AD (Morales et al., 2014). Moreover, amyloid β1–42 oligomers (AβOs), rather than Aβ fibrillar deposits, significantly inhibit neuronal viability; AβOs are considered to be toxic and inflammatory-inducing peptides (Dahlgren et al., 2002). Therefore, it would be valuable approach to develop a drug which inhibits Aβ oligomerization and neuroinflammation.

The seeds of Zizyphus jujuba var. spinosa (Rhamnoceae) have traditionally been used as hypnotic or sedative drugs to treat psychiatric disorders in China, Japan, and Korea (Zhu, 1998). In addition, various compounds including jujubosides, jujubogenin, and sanjoinine in Z. jujuba var. spinosa are evaluated as active constituents against insomnia (Zhang et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2008; Han et al., 2009). Recently, we reported that spinosin (2″-β-O-glucopyranosyl swertisin), a C-glycoside flavonoid isolated from the seeds of Z. jujuba var. spinosa has an ameliorating effect on scopolamine-induced memory impairment (Jung et al., 2014). However, whether spinosin has neuroprotective effects on AβO-induced cognitive impairment in a mouse model of AD remains unknown. If spinosin exerts neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activities, it would be a potential therapeutic candidate for AD.

In the present study, we evaluated whether spinosin has neuroprotective effects and ameliorates AβO-induced memory impairment in mice. To examine the memory-ameliorating effects and mechanisms of neuroprotection, we used several behavioral tasks, including the Y-maze task and the passive avoidance task. In addition, Western blot and immunohistochemistry analyses were also employed to investigate the effects of spinosin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male ICR mice (25–30 g, 6 weeks old) were purchased from the Orient Co. Ltd, a branch of the Charles River Laboratories (GyeongGi-do, Korea). The mice were housed 5 per cage under a 12 h light/dark cycle (light on 07:30–19:30 h) at a constant temperature (23 ± 1°C) and relative humidity (60 ± 10%) and provided food and water ad libitum. The animals were treated and maintained in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Guidelines of Kyung Hee University. All experimental protocols were approved through the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kyung Hee University (approval number; KHP-2013-01-04).

Materials

Spinosin was provided by one of the authors (D.S. Jang) and the purity of this sample was greater than 99%. The Aβ1–42 protein fragment and donepezil hydrochloride monohydrate were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody was purchased from Invitrogen Co. (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Rat polyclonal anti-OX-42 and goat polyclonal anti-ChAT antibodies were purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA, USA). All other materials were of the highest grade commercially available.

Thioflavin T assay

Inhibitory effect of spinosin on AβO formation was determined using a previously described method (Choi et al., 2012). Briefly, Aβ1–42 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and resuspended in distilled water. The concentration of the Aβ1–42 solution was 100 μM. To prepare the thioflavin T (ThT, 5 mM) stock solution, ThT was dissolved in DMSO and the solution was stored at −20°C. The ThT stock solution was diluted in 50 mM glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 8.5) to generate a 25 μM working solution. Spinosin was dissolved in DMSO and screened at concentrations of 4, 20, 100 and 500 μg/mL. To measure the inhibitory effect of spinosin on AβO formation, the Aβ1–42 solution was incubated in the presence of spinosin (4, 20, 100 and 500 μg/mL, with a final 1% DMSO concentration). The mixture was incubated for 24 h at 4°C. The resultant was mixed with the ThT working solution, and the fluorescence intensity was monitored using a FLUOstar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Germany) at 25°C (excitation, 470 nm; emission, 520 nm). The relative fluorescence intensity was measured to determine the amount of oligomeric aggregates formed in solution. The following equation was used to estimate AβO aggregation based on the fluorescence intensity: AβO aggregation (arbitrary unit, AU)=(F2-F0)/(F1-F0)(F0, dye alone fluorescence; F1, Aβ fluorescence; F2, Aβ+spinosin fluorescence). All measurements were obtained from 2 individual experiments with duplicate.

AβO injection and drug administration

Soluble oligomers were generated as previously described, with slight modifications (Moon et al., 2014). Briefly, Aβ1–42 protein was dissolved in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml at room temperature for 3 days. The peptides were aliquoted and vacuum dried for 1 h. The aliquoted peptides were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO to a final concentration of 1 mM. The protein concentration of the solution was determined using a Bradford assay. Subsequently, the stock was directly diluted into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 8.5) at 50 μM and incubated at 4°C for 24 h to generate oligomeric Aβ protein. The 60 mice were used and randomly divided into 6 groups (10 mice/group) and administered either AβO or PBS (3 μl/3 min, i.c.v.) into the right lateral ventricle at stereotaxic coordinates (AP, −0.2 mm; ML, +1.0 mm; DV, −2.5 mm) taken from the atlas of the mouse brain (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001) under anesthesia using a mixture of N2O and O2 (70:30) containing 2% isoflurane. After 5 min, the needle was removed using three intermediate steps with a 1-min inter-step delay to minimize backflow, and mice were maintained on a warm pad until awakened. Sham animals were injected with the same amount of PBS (3 μl) using an identical manner. Immediately after AβO injection, the mice were administered spinosin (5, 10, or 20 mg/kg, p.o), and the mice were administered spinosin injections once a day for 6 days. The mice in the control group were orally administered 10% Tween 80 solution. Behavioral tests were conducted at 24 h after the last administration of spinosin.

Passive avoidance task

Acquisition and retention trials of the passive avoidance task were performed at 7 and 8 days, respectively, after AβO injection. Testing was performed in a box comprising of two identical chambers (20×20×20 cm) with one illuminated with 50-W bulb and a non-illuminated chamber separated with a guillotine door (5×5 cm). The floor of the non-illuminated compartment comprised 2 mm stainless steel rods spaced 1 cm apart as previously described (Lee et al., 2013). The mice were administered either spinosin (5, 10 or 20 mg/kg, p.o.) or donepezil (5 mg/kg, p.o.) for 6 days, and the last treatment was administered at 24 h before the acquisition trial. The control group received 10% Tween 80 solution at the same volume as used in the experimental groups. The mice were initially placed in the illuminated compartment during the acquisition trial. The door between the two compartments was opened after 10 s. The door automatically closed when the mice entered the non-illuminated compartment, and a 3-s electrical foot shock (0.5 mA) was delivered through the stainless steel rods. The mice that did not enter the non-illuminated compartment within 60 s after opening the door were excluded from retention trial. The retention trial was conducted at 24 h after the acquisition trial when individual mice were returned to the illuminated compartment. The time required for the mouse to enter the dark compartment after opening the door was defined as latency in both trials. The latencies were recorded for up to 300 s.

Y-maze task

The Y-maze task was performed at 7 days after AβO injection. The Y-maze is a three-arm (40-cm-long and 3-cm-wide with 12-cm-high walls) horizontal maze in which the arms were symmetrically disposed at 120° angles from one another. The maze floor and walls were constructed of dark opaque polyvinyl plastic as previously described (Jung et al., 2014). The mice were initially placed within one arm, and the sequence (i.e., ABCCAB, etc.) and number of arm entries were manually recorded for each mouse over an 8-min period. Alternations were defined as entries into all three arms on consecutive choices (i.e., ABC, CAB, or BCA but not BAB). The mice were administered either spinosin (5, 10 or 20 mg/kg, p.o.) or donepezil (5 mg/kg, p.o.) for 6 days, and the last treatment was administered at 24 h before the test. The control group animals received 10% Tween 80 solution rather than spinosin or donepezil. Between each test, the maze arms were thoroughly sprayed with water to remove residual odors and residues. The alternation score (%) for each mouse was defined as the ratio of the actual number of alternations to the possible number (defined as the total number of arm entries minus two multiplied by 100) using the following equation: % Alternation= [(Number of alternations)/(Total arm entries-2)]×100. The number of arm entries was used as an indicator of locomotor activity.

Western blot analysis

The mice were sacrificed at 24 h after the last spinosin administration (20 mg/kg) for Western blotting. The isolated hippocampal tissues were homogenized in ice-chilled Tris-HCl buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) containing 0.32 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM sodium orthovana-date, and one protease inhibitor tablet per 50 ml of buffer. The homogenates (15 μg for protein) were subsequently subjected to SDS-PAGE (8% gel) under reducing conditions. The proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes in transfer buffer [25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 192 mM glycine and 20% v/v methanol] at 400 mA for 2 h at 4°C. The Western blots were blocked at room temperature for 2 h in 5% skim milk and incubated with anti-GFAP, anti-OX-42 or anti-ChAT antibodies (1:1000 dilution) overnight at 4°C, followed by washing ten times with Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 (TBST). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with a 1:3000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature, washed ten times with TBST, and developed with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). The membrane was analyzed using the LAS-4000 mini bio-imaging program (Fuji-film Life Science USA, Stamford, CT, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

After AβO injection, the mice were treated with spinosin (20 mg/kg) or 10% Tween 80 for 7 days. The mice were anesthetized using a mixture of N2O and O2 (70:30) containing 2% isoflurane 24 h after the last administration, and transcardially perfused with 50 mM PBS (pH 7.4) followed by ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were removed and postfixed overnight in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) containing 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by immersion in a solution containing 30% sucrose in 50 mM PBS, and storage at 4°C until sectioning. The frozen brain samples were coronally sectioned. Sections from −1.58 to −2.30 mm were obtained for the hippocampal area, based on the atlas of the mouse brain (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). Free-floating sections were incubated for 24 h in PBS (4°C) containing anti-GFAP (1:1000 dilution), anti-OX-42 (1:1000 dilution) or anti-ChAT (1:1000 dilution) antibodies, 0.3% Triton X-100, 0.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 1.5% normal horse serum, as previously described (Lee et al., 2012).

Statistics

The data are expressed as the means ± S.E.M. The latencies in the passive avoidance task, spontaneous alternations in the Y-maze task, and the data from the Western blot and immunohistochemistry experiments were analyzed using oneway analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

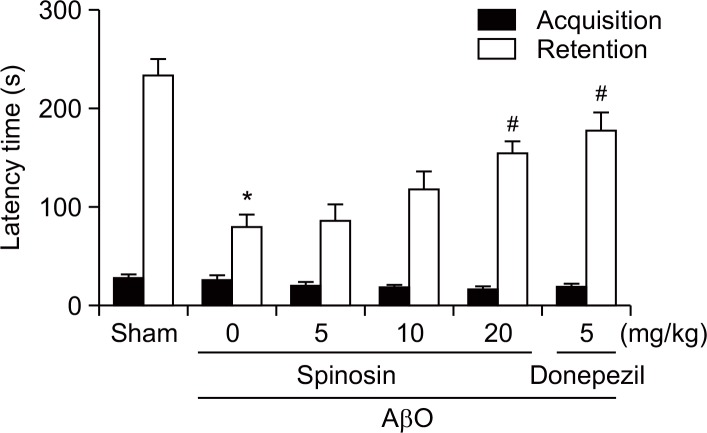

Subchronic administration of spinosin ameliorated AβO-induced cognitive dysfunction in the passive avoidance task

The passive avoidance task was employed to investigate the memory-ameliorating effects of spinosin. Significant group effects in the step-through latency were observed in the retention trial performed 24 h after the acquisition trial [F (5, 49)=13.28, p<0.05]. The reduction in the step-through latency in the AβO-injected group was significantly reversed in the spinosin-treated group (20 mg/kg, p<0.05; Fig. 1). During the acquisition trial, no significant differences in the step-through latencies between the groups were observed.

Fig. 1.

Effects of subchronic spinosin treatment on Aβ1–42 oligomer (AβO)-induced memory impairment in the passive avoidance task. Animals were intracerebroventricularly injected with AβO protein (50 μmol/3 μl) or sterile saline (3 μl). Immediately following Aβ1–42 oligomer protein injection, spinosin (5, 10, or 20 mg/kg), dissolved in 10% Tween 80, was administered for 6 days (once a day, p.o.). The last administration of spinosin or vehicle (same volume of 0.9% normal saline) was conducted at 24 h prior to performing the passive avoidance task. A 5-min retention trial was performed at 24 h after the acquisition trial. The data represent the means ± S.E.M. (n=9–10/group). *p<0.05 compared with the sham group, #p<0.05 compared with the AβO-treated group.

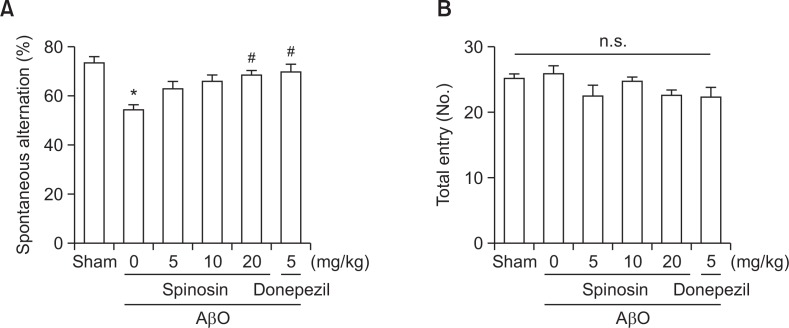

Subchronic administration of spinosin ameliorated memory impairment induced through AβO in the Y-maze task

The Y-maze task was performed to examine the effect of spinosin on spontaneous alternation behaviors in mice. A significant group effect was observed in spontaneous alternation behaviors after the subchronic administration of spinosin [F (5, 50)=6.0141, p<0.05; Fig. 2]. The percentage of spontaneous alternations in the AβO-injected group was significantly lower than that in the vehicle-treated control group (p<0.05, Fig. 2A), and the reduction of spontaneous alternation was significantly ameliorated following the administration of spinosin (20 mg/kg, p.o.) or donepezil (5 mg/kg, p.o.) (p<0.05, Fig. 2A). Therefore, we adopted 20 mg/kg as the administered dosage for the remaining in vivo studies. The mean number of the arm entries was similar across all experimental groups (Fig. 2B), suggesting that general locomotor activity was not affected after spinosin treatment.

Fig. 2.

Effects of subchronic spinosin treatment on Aβ1–42 oligomer (AβO)-induced memory impairment in the Y-maze task. The animals were intracerebroventricularly injected with AβO protein (50 μmol/3 μl) or sterile saline (3 μl). Immediately following Aβ1–42 oligomer protein injection, spinosin (5, 10, or 20 mg/kg), dissolved in 10% Tween 80, was administered for 6 days (once a day, p.o.). The last administration of spinosin or vehicle (same volume of 0.9% normal saline) was conducted at 1 h before performing the Y-maze task. The mice were introduced to the Y-maze task for 8 min. The data represent the means ± S.E.M. (n=8–10/group). *p<0.05 compared with the sham group, #p<0.05 compared with the AβO-treated group. n.s., no significance.

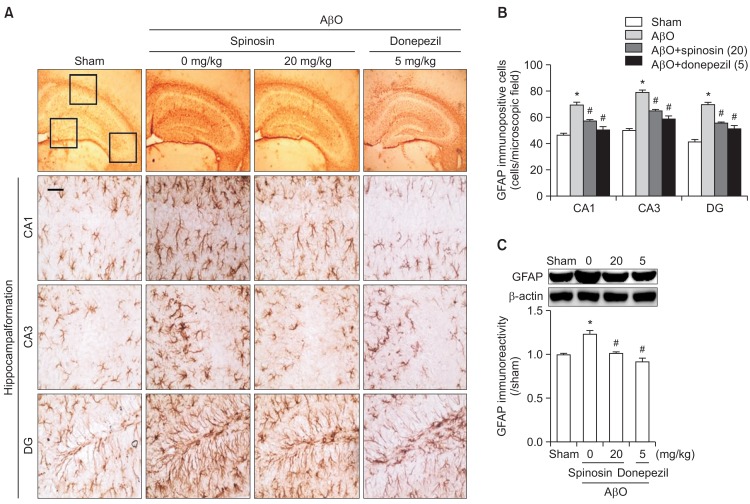

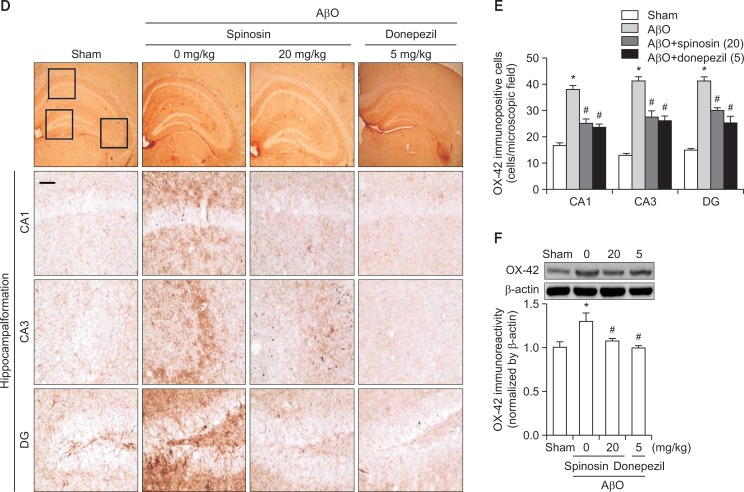

Subchronic administration of spinosin attenuated glial cell activation induced through AβO injection

To examine whether the glial cell activations induced after AβO injection were attenuated through subchronic spinosin administration, we performed immunohistochemistry using either an anti-GFAP or an anti-OX-42 antibody. Representative photomicrographs of the GFAP-immunopositive cells in the CA1, CA3, and DG regions of the hippocampal formation are shown in Fig. 3A. Negligible GFAP-positive cells were observed in the sham control groups, whereas in the AβO-injected group, the GFAP-immunopositive cells in the hippocampal region were hypertrophic and the numbers of cells were increased. The administration of spinosin (20 mg/kg) or donepezil (5 mg/kg), as a positive control, markedly reduced the number of GFAP-immunopositive cells compared with the AβO-injected group [CA1, F (3,12)=24.89, p<0.05; CA3, F (3,12)=48.76, p<0.05; DG, F (3,12)=38.68, p<0.05, Fig. 3B]. Consistent with the results of the GFAP-immunohistochemistry, the Western blot analysis showed that GFAP-immunoreactivity in the hippocampal tissue was significantly increased after the injection of the AβO, and this increase was attenuated by spinosin (20 mg/kg) or donepezil (5 mg/kg) [F (3,12)=18.97, p<0.05, Fig. 3C].

Fig. 3.

The effects of subchronic spinosin treatment on Aβ1–42 oligomer (AβO)-mediated glial cell activation. (A) Microphotographs of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-immunopositive cells, (B) the numbers of GFAP immunopositive cells in the CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus (DG) regions of the hippocampal formation (n=4), and (C) a Western blot of the GFAP immunoreactivity in the hippocampus are presented (n=3). (D) Microphotographs of CD11b (OX-42)-immunopositive cells, (E) the numbers of OX-42-immunopositive cells in the CA1, CA3, and DG regions of the hippocampal formation (n=4), and (F) a Western blot of OX-42 immunoreactivity in the hippocampus are presented (n=4). The rectangular subsets in the top panel showing the CA1, CA3, and DG were magnified in the lower panel. The data represent the means ± S.E.M. *p<0.05 compared with the sham group, #p<0.05 compared with the AβO-injected group. Magnification, 400 ×; Bar, 50 μm.

Representative photomicrographs of the OX-42-immunopositive cells in the CA1, CA3, and DG regions of the hippocampal formation are presented in Fig. 3D. In the sham control group, the OX-42-immunopositive microglial cells were scattered and ramified. However, the OX-42-immunopositive cells in the Aβ1–42 peptide-injected group were condensed and activated, particularly in the DG region. Moreover, Aβ1–42 peptide-induced microglial cell activation was attenuated after treatment with 20 mg/kg of spinosin or 5 mg/kg of donepezil [CA1, F (3,12)=38.82, p<0.05; CA3, F (3,12)=44.52, p<0.05; DG, F (3,12)=54.16, p<0.05, Fig. 3E]. The Western blot analysis also confirmed the OX-42-immunohistochemistry results presented above; OX-42-immunoreactivity was significantly increased after AβO injection, and spinosin (20 mg/kg) or donepezil (5 mg/kg) reversed this increase [F (3,12)=5.273, p<0.05, Fig. 3F].

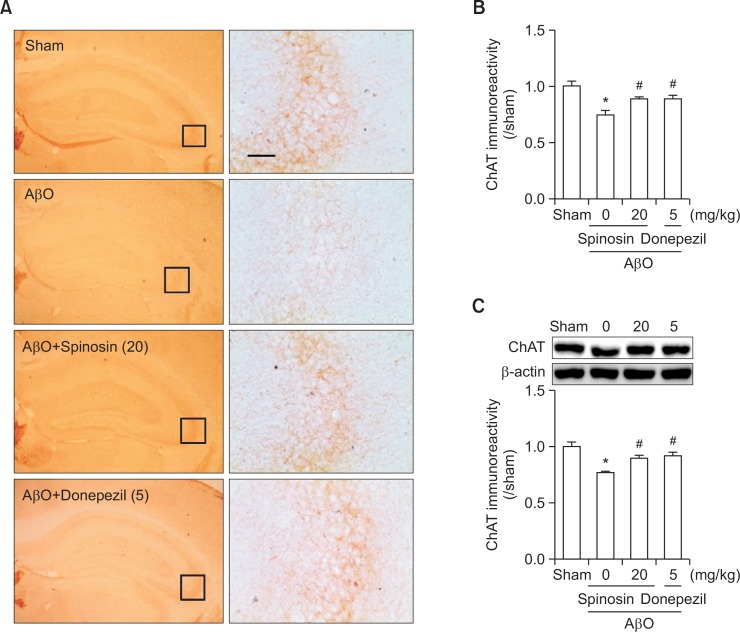

Subchronic administration of spinosin ameliorated the reduction in ChAT expression induced through AβO injection

We performed immunohistochemistry and Western blot analyses to investigate whether spinosin exerts protective effects against the cholinergic neurotransmitter system. Representative photomicrographs of ChAT-immunopositive cells in the CA3 region of the hippocampus are shown in Fig. 4A. The optical density of hippocampal ChAT immunoreactivity, particularly in the CA3 region, was markedly reduced after AβO injection, and this effect was ameliorated after treatment with 20 mg/kg of spinosin or 5 mg/kg of donepezil [F (3,12)=7.790, p<0.05, Fig. 4B]. Similarly, Western blot analysis revealed that the ChAT-immunoreactivity in the hippocampus was significantly reduced after the AβO injection, and spinosin or donepezil administration reversed this reduction to the sham level [F (3,12)=11.30, p<0.05, Fig. 4C].

Fig. 4.

The effects of subchronic spinosin treatment on Aβ1–42 oligomer (AβO) injection-induced decrease in choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) levels. (A) Photomicrographs of ChAT immunoreactivity in the hippocampal regions, (B) the optical density (O.D) of ChAT immunoreactivity in the hippocampal CA3 region (n=3–4/group), and (C) a Western blot of ChAT in the hippocampus (n=4) are presented. The right panel in A was magnified from each of the rectangular subsets in the left panel. The data represent the means ± S.E.M. *p<0.05 compared with the sham group, #p<0.05 compared with the AβO-injected group. Magnification, 400 ×; Bar, 50 μm.

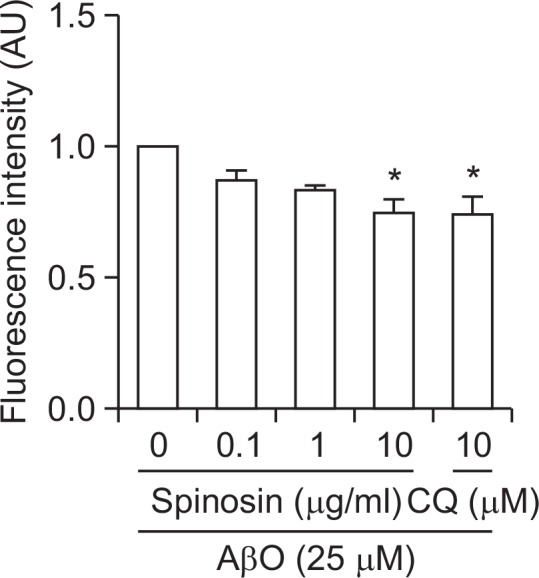

The effects of spinosin on the formation of AβO in vitro

In addition to the anti-inflammatory effect of spinosin, an in vitro assay was conducted to investigate whether spinosin prevents Aβ1–42 oligomerization. The oligomer formation was measured as the amount of ThT fluorescence associated with the oligomers. When we measured the ThT fluorescence intensity in the absence of spinosin, Aβ1–42 oligomers were readily generated through the incubation of Aβ1–42 protein (25 μM) at pH 7.4 and 4°C. Spinosin (0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml) significantly suppressed the formation of Aβ1–42 oligomers in a dose-dependent manner as observed in clioquinol (10 μM), a positive control. In the presence of spinosin (10 μg/ml), oligomerization was reduced 82% compared with the control (Fig. 5). The data were obtained from quadruple individual experiments with duplicate.

Fig. 5.

Inhibitory effects of spinosin on Aβ1–42 oligomerization in vitro. The Aβ1–42 oligomer (AβO) was incubated at 4 °C for 24 h in the presence or absence of spinosin. Oligomer formation was detected using a Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assay. The data represent the means ± S.E.M. (n=4). *p<0.05 compared with AβO-treated group. CQ, clioquinol.

DISCUSSION

We investigate anti-amnesic or anti-dementic herbal agents that affect the central nervous system. Previously, we reported that the ethanolic extract of Zizyphus jujuba var. spinosa ameliorates cognitive function in scopolamine-induced memory impairment and suggested that spinosin, a C-glycosylflavone from Zizyphus jujuba var. spinosa, is an active constituent of this extract (Lee et al., 2013). In addition, we also reported that spinosin exhibits anti-amnesic effects in part through the antagonistic properties of the 5-HT1A receptor. 5-HT1A receptor ligands regulate the release of acetylcholine activity at the pre-synaptic sites of cholinergic nerves (Jung et al., 2014). Thus, the putative attenuation of Aβ-induced neuronal dysfunctions through spinosin implicates this compound as a potential therapeutic for treating AD.

We observed that the subchronic administration of spinosin significantly ameliorated AβO-induced memory impairment. Indeed, AβO, rather than insoluble Aβ plaques, is the primary toxic species underlying AD pathogenesis (Hyman et al., 1984; Resende et al., 2007). While both forms have been detected in the AD brain, soluble AβOs are more associated with AD severity than amyloid plaques containing insoluble Aβ fibrillar deposits (Lue et al., 1999; McLean et al., 1999; Tomic et al., 2009). Thus we employed an AβO injection mouse model in the present study. To avoid the previously observed memory enhancing effect of spinosin (Jung et al., 2014), the last administration was conducted at 24 h before the behavioral tests in the present study. As a result, the subchronic administration of spinosin ameliorated AβO-induced memory impairment in the passive avoidance task and the Y-maze task. These results indicate that the memory-ameliorating effect of spinosin might be derived from the prevention of AβO-induced neuronal damage rather than the acute memory enhancing effects.

In addition, we observed that spinosin decreased the increased AβO-induced immunoreactivity of GFAP or OX-42 in the hippocampus. Activated astrocytes and microglia act as markers of pathological events in the CNS, and these cells are also activated in the AD brain (Nagele et al., 2004). Activated glial cells release various inflammatory mediators under pathological conditions, such as the release of superoxide, nitric oxide or cytokines (Block et al., 2007; Mizuno, 2012). Consistent with the results of previous studies (Dinamarca et al., 2006; Moon et al., 2011), activated astrocytes (GFAP positive) and microglia (OX-42-positive) were markedly increased after the injection of the AβO in the present study. The immunoreactivity of AβO-activated astrocytes and microglia was significantly decreased after subchronic spinosin administration. These results indicate that spinosin attenuated AβO-induced glial cell activation, resulting in neuroprotection through the anti-inflammatory effects of this compound. In addition, spinosin exhibited anti-oligomerogenic effects in vitro. Protein aggregation into Aβ oligomers involves the misfolding of soluble Aβ proteins into insoluble Aβ fibrils comprising cross-β-sheets, and these aggregates have been detected as common symptoms in many neurodegenerative diseases, including AD (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002). Accumulating evidence has shown that Aβ oligomerization or fibrillization is critical for neurodegeneration (Bloom et al., 2005; Glabe, 2005), suggesting that the prevention of this process might be an effective approach for the treatment of AD. For examples, clioquinol or curcumin has been reported as an anti-oligomerogenic or anti-fibrillogenic agent and it was suggested as a candidate for AD therapy (Yang et al., 2005). To our knowledge, however, any compound is not approved for clinical use against anti-oligomerization. Although numerous hurdles should be overcomed for clinical trial, the present study suggests that spinosin alleviates not only AβO-induced neurotoxicity, but also AβO-induced neuronal dysfunctions.

ChAT is abundant in cholinergic neurons and is responsible for the synthesis of acetylcholine (Strauss et al., 1991). Moreover, ChAT expression is reduced in the hippocampus of AD brain (Armstrong et al., 1986). The change in ChAT activity is highly associated with the severe impairment of spatial learning and memory. Many studies have suggested the possibility that AβO suppresses the activity of ChAT (Nunes-Tavares et al., 2012). In the present study, hippocampal levels of ChAT expression were depleted through AβO and reversed through the subchronic administration of spinosin. These results indicate that the memory-ameliorating effects of spinosin on AβO-induced cognitive dysfunction might partially reflect the restoration of ChAT expression in the hippocampus.

Several studies have indicated that spinosin exhibits 5-HT1A receptor antagonistic properties (Wang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012; Jung et al., 2014). However, the effects of 5-HT1A receptor agonists or antagonists on Aβ-induced pathological symptoms have been rarely investigated. Until recently, it is not clear whether the 5-HT1A receptor antagonistic properties of spinosin influence the neuroprotective effects of this compound. According to the results of previous studies, compounds with structures similar to spinosin exhibit neuroprotective effects on Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, with anti-inflammatory properties (Kim et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2014). Therefore, we proposed that the effects of spinosin reflect the structural specificity of this compound, similar to flavonoid or polyhydroxylated compound. Further studies are needed to determine the precise neuroprotection mechanism of spinosin.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that spinosin is effective against AβO-induced memory impairment. These memory-ameliorating effects were derived from the anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective activities of spinosin. Thus, although the present study did not provide clinical outcomes, these findings suggest that spinosin is a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of AD through the targeting of both lowered cholinergic- and Aβ-induced cognitive dysfunctions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported through a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) through the Korean Government (NRF-2013R1A1A2004398).

REFERENCES

- Armstrong DM, Bruce G, Hersh LB, Terry RD. Choline acetyltransferase immunoreactivity in neuritic plaques of Alzheimer brain. Neurosci Lett. 1986;71:229–234. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90564-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom GS, Ren K, Glabe CG. Cultured cell and transgenic mouse models for tau pathology linked to beta-amyloid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1739:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Chen YF, Tsai HY. What is the effective component in suanzaoren decoction for curing insomnia? Discovery by virtual screening and molecular dynamic simulation. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2008;26:57–64. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2008.10507223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang K, Koo EH. Emerging therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;54:381–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DY, Lee JW, Peng J, Lee YJ, Han JY, Lee YH, Choi IS, Han SB, Jung JK, Lee WS, Lee SH, Kwon BM, Oh KW, Hong JT. Obovatol improves cognitive functions in animal models for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2012;120:1048–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Price DL, DeLong MR. Alzheimer’s disease: a disorder of cortical cholinergic innervation. Science. 1983;219:1184–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.6338589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL. Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: current and future therapeutic approaches. Rev Neurol Dis. 2004;1:60–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB, Jr, Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-beta peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinamarca MC, Cerpa W, Garrido J, Hancke JL, Inestrosa NC. Hyperforin prevents beta-amyloid neurotoxicity and spatial memory impairments by disaggregation of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta-deposits. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:1032–1048. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis PT, Palmer AM, Snape M, Wilcock GK. The cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of progress. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1999;66:137–147. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabe CC. Amyloid accumulation and pathogensis of Alzheimer’s disease: significance of monomeric, oligomeric and fibrillar Abeta. Subcell Biochem. 2005;38:167–177. doi: 10.1007/0-387-23226-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H, Ma Y, Eun JS, Li R, Hong JT, Lee MK, Oh KW. Anxiolytic-like effects of sanjoinine A isolated from Zizyphi Spinosi Semen: possible involvement of GABAergic transmission. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatrics. 1997;52(Suppl 2):S4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman BT, Van Hoesen GW, Damasio AR, Barnes CL. Alzheimer’s disease: cell-specific pathology isolates the hippocampal formation. Science. 1984;225:1168–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.6474172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung IH, Lee HE, Park SJ, Ahn YJ, Kwon G, Woo H, Lee SY, Kim JS, Jo YW, Jang DS, Kang SS, Ryu JH. Ameliorating effect of spinosin, a C-glycoside flavonoid, on scopolamine-induced memory impairment in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;120:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Kim S, Jeon SJ, Son KH, Lee S, Yoon BH, Cheong JH, Ko KH, Ryu JH. The effects of acute and repeated oroxylin A treatments on Abeta(25–35)-induced memory impairment in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo EH, Lansbury PT, Jr, Kelly JW. Amyloid diseases: abnormal protein aggregation in neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9989–9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.9989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HE, Kim DH, Park SJ, Kim JM, Lee YW, Jung JM, Lee CH, Hong JG, Liu X, Cai M, Park KJ, Jang DS, Ryu JH. Neuroprotective effect of sinapic acid in a mouse model of amyloid beta(1–42) protein-induced Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2012;103:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HE, Lee SY, Kim JS, Park SJ, Kim JM, Lee YW, Jung JM, Kim DH, Shin BY, Jang DS, Kang SS, Ryu JH. Ethanolic extract of the seed of Zizyphus jujuba var. spinosa ameliorates cognitive impairment induced by cholinergic blockade in mice. Biomol Ther. 2013;21:299–306. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2013.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lublin AL, Link CD. Alzheimer’s disease drug discovery: in vivo screening using Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for beta-amyloid peptide-induced toxicity. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2013;10:e115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, Brachova L, Shen Y, Sue L, Beach T, Kurth JH, Rydel RE, Rogers J. Soluble amyloid beta peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:853–862. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65184-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CA, Cherny RA, Fraser FW, Fuller SJ, Smith MJ, Beyreuther K, Bush AI, Masters CL. Soluble pool of Abeta amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:860–866. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<860::AID-ANA8>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T. The biphasic role of microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:737846. doi: 10.1155/2012/737846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon M, Choi JG, Kim SY, Oh MS. Bombycis excrementum reduces amyloid-beta oligomer-induced memory impairments, neurodegeneration, and neuroinflammation in mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41:599–613. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon M, Choi JG, Nam DW, Hong HS, Choi YJ, Oh MS, Mook-Jung I. Ghrelin ameliorates cognitive dysfunction and neurodegeneration in intrahippocampal amyloid-beta(1–42) oligomer-injected mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23:147–159. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales I, Guzman-Martinez L, Cerda-Troncoso C, Farias GA, Maccioni RB. Neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. A rational framework for the search of novel therapeutic approaches. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:112. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagele RG, Wegiel J, Venkataraman V, Imaki H, Wang KC. Contribution of glial cells to the development of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2004;25:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Tavares N, Santos LE, Stutz B, Brito-Moreira J, Klein WL, Ferreira ST, de Mello FG. Inhibition of choline acetyltransferase as a mechanism for cholinergic dysfunction induced by amyloid-beta peptide oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19377–19385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.321448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KB. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Resende R, Pereira C, Agostinho P, Vieira AP, Malva JO, Oliveira CR. Susceptibility of hippocampal neurons to Abeta peptide toxicity is associated with perturbation of Ca2+ homeostasis. Brain Res. 2007;1143:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss WL, Kemper RR, Jayakar P, Kong CF, Hersh LB, Hilt DC, Rabin M. Human choline acetyltransferase gene maps to region 10q11–q22.2 by in situ hybridization. Genomics. 1991;9:396–398. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90273-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomic JL, Pensalfini A, Head E, Glabe CG. Soluble fibrillar oligomer levels are elevated in Alzheimer’s disease brain and correlate with cognitive dysfunction. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;35:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LE, Cui XY, Cui SY, Cao JX, Zhang J, Zhang YH, Zhang QY, Bai YJ, Zhao YY. Potentiating effect of spinosin, a C-glycoside flavonoid of Semen Ziziphi spinosae, on pentobarbital-induced sleep may be related to postsynaptic 5-HT(1A) receptors. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LE, Zhang XQ, Yin YQ, Zhang YH. Augmentative effect of spinosin on pentobarbital-induced loss of righting reflex in mice associated with presynaptic 5-HT1A receptor. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;64:277–282. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu PX, Wang SW, Yu XL, Su YJ, Wang T, Zhou WW, Zhang H, Wang YJ, Liu RT. Rutin improves spatial memory in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice by reducing Abeta oligomer level and attenuating oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Behav Brain Res. 2014;264:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Lim GP, Begum AN, Ubeda OJ, Simmons MR, Ambegaokar SS, Chen PP, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid beta oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5892–5901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SS, Jo SA. Mechanisms of amyloid-beta peptide clearance: potential therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s disease. Biomol Ther. 2012;20:245–255. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2012.20.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Ning G, Shou C, Lu Y, Hong D, Zheng X. Inhibitory effect of jujuboside A on glutamate-mediated excitatory signal pathway in hippocampus. Planta Med. 2003;69:692–695. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. Chinese Materia Medica: Chemistry, Pharmacology and Applications. Harwood Academic Publishers; The Netherlands: 1998. pp. 513–515. [Google Scholar]