Abstract

Bone-marrow-derived stem cells have displayed the potential for myocardial regeneration in animal models as well as in clinical trials. Unfractionated bone marrow mononuclear cell (MNC) population is a heterogeneous group of cells known to include a number of stem cell populations. Cells in the side population (SP) fraction have a high capacity for differentiation into multiple lineages. In the current study, we investigated the role of murine and human bone-marrow-derived side population cells in myocardial regeneration. In these studies, we show that mouse bone-marrow-derived SP cells expressed the contractile protein, alpha-actinin, following culture with neonatal cardiomyocytes and after delivery into the myocardium following injury. Moreover, the number of green-fluorescent-protein-positive cells, of bone marrow side population origin, increased progressively within the injured myocardium over 90 days. Transcriptome analysis of these bone marrow cells reveals a pattern of expression consistent with immature cardiomyocytes. Additionally, the differentiation capacity of human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor stimulated peripheral blood stem cells were assessed following injection into injured rat myocardium. Bone marrow mononuclear cell and side population cells were both readily identified within the rat myocardium 1 month following injection. These human cells expressed human-specific cardiac troponin I as determined by immunohistochemistry as well as numerous cardiac transcripts as determined by polymerase chain reaction. Both human bone marrow mononuclear cells and human side population cells augmented cardiac systolic function following a modest drop in function as a result of cryoinjury. The augmentation of cardiac function following injection of side population cells occurred earlier than with bone marrow mononuclear cells despite the fact that the number of side population cells used was one tenth that of bone marrow mononuclear cells (9 × 105 cells per heart in the MNC group compared to 9 × 104 per heart in the SP group). These results support the hypotheses that rodent and human-bone-marrow derived side population cells are capable of acquiring a cardiac fate and that human bone-marrow-derived side population cells are superior to unfractionated bone marrow mononuclear cells in augmenting left ventricular systolic function following cryoinjury.

Keywords: Human Bone-Marrow-Derived Stem Cells, Side Population Cells, Mononuclear Cells, Myocardial Regeneration, Cryoinjury

Introduction

In recent years, there has been intense interest in the field of cardiac stem cell research. New hopes of revolutionizing the practice of cardiovascular medicine range from restoration of contractile function following myocardial injury to regeneration of cardiac pacemaker cells and even repair of degenerative cardiac valves. Numerous clinical trials attempting to promote myocardial regeneration have been performed with variable results [1–8]. In order to clearly delineate the role of cell-based therapeutic strategies in myocardial regeneration, it is important to identify the fate of therapeutic stem cells and to characterize the regenerative potential of different stem cell populations.

Bone-marrow-derived mononuclear cells (MNCs) have been the most widely used stem cell population in clinical trials [9, 10]. This is, perhaps, attributable to the relative ease of obtaining a large numbers of autologous cells and to their known therapeutic potential in bone marrow transplantation (the only known use of regenerative medicine in modern day medical practice). The MNC population is a heterogeneous group of cells that is primarily comprised of differentiated cells (for example, monocytes form about 50% of the MNC population) and small percentages of stem cells such as CD34+, Lin−, C-kit+, mesenchymal stem cells, and side population (SP) cells [11].

The term “side population” refers to the flow cytometry profile of a rare group of cells that can be identified based on their ability to efflux the nuclear dye Hoescht 33342 [12–16]. This characteristic is attributable to the multidrug-resistant adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding cassette transporter ABCG2 located on their cell membrane [16–18]. Side population cells can be isolated from virtually every organ and have been shown to possess numerous stem cell characteristics [12–16]. Our group has previously isolated these cells from the adult myocardium and demonstrated their ability to express cardiac markers [16]. In the present study, we demonstrate the ability of both rodent and human bone-marrow-derived SP cells to repopulate the injured myocardium and express cardiac markers following myocardial injury. Moreover, we demonstrate that human bone-marrow-derived SP cells are capable of regenerating the injured rodent myocardium with greater efficiency than total MNC population.

Material and Methods

BM SP Co-culture and Differentiation Assay

Murine neonatal cardiomyocytes were harvested as previously described [19] and plated at a density of 5 × 105 cells per milliliter in cardiomyocyte media (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, high glucose 67%, medium 199 17%, horse serum 10%, fetal bovine serum 5%, and Pen-Strep 1%) into 24-well culture plates containing fibronectin-coated glass coverslips. 4’,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the media at a final concentration of 0.01 mg/ml. After 48 h, bone marrow was harvested from 2-month-old enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) mice (Jackson Labs; Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and prepared as described below. Five thousand green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive cardiac SP cells were obtained and added to the wild-type cardiac culture. After 14 days, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS+); the coverslip was removed and the following staining protocol was performed. Cells were permeabilized (0.1% triton in PBS for 2 min), blocked (1.0% bovine serum albumin/PBS for 15 min), and incubated with the primary antisera, monoclonal anti-alpha-actinin clone EA-53 (1:150 dilution, Sigma), for 1 h at room temperature. Next, the sections were rinsed and incubated with lissaminerhodamine-conjugated goat antimouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; 1:50; Jackson Immunoresearch) for 30 min. Slides were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and fluorescence images were collected using a Zeiss Axioplan2i microscope.

Myocardial Cryoinjury

On the day prior to scheduled cryoablative surgery, the human cells were isolated and incubated overnight with DAPI. On the morning of the procedure, DAPI-stained human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were washed, counted, and resuspended in X-vivo 20 and/or murine bone marrow side population (BMSP) cells were isolated from the eGFP mice. NOD/SCID or ROSA26 mice and athymic nude rats (Harlan Tecklad, USA) were anesthetized with isoflurane, intubated, and ventilated using a small animal ventilator (Harvard Apparatus) [20]. A left thoracotomy was performed and the heart was exposed in order to induce cryoinjuries consistently in the same area of the left ventricle (LV). A transmural cryoinjury was induced by exteriorizing the heart and applying a liquid-nitrogencooled probe to the LV for 2–3 and 4–6 s for the mice and rats, respectively. The size of the probe used to induce injury was 2.18 by 2.52 mm. The resulting injury was easily visualized and highly reproducible [20]. For the murine studies, 5 min following injury, 100,000 GFP+ SP cells resuspended in 15 µl were injected into the healthy myocardium adjacent to the well-demarcated cryoinjury zone. For the rat studies, 5 min following cryoinjury, human cells were injected into the healthy myocardium at three sites adjacent to the well-demarcated cryoinjury zone. Each site received 15 µl of cells (~ 300,000 cells per site for MNC or 30,000 cells per site for SP cells). Therefore, the total number of cells injected per animal were 9 × 105 cells per animal in the MNC group and 9 × 104 per animal in the SP group. All injections were done using a Hamilton syringe and 30-gauge needle equipped with a protective sleeve to prevent inadvertent injection of the cells into the ventricular cavity. Baseline left ventricular fractional shortening (FS) was obtained in conscious rats using a Vivid7 Pro echocardiography machine equipped with an 11 mHz transducer (GE). Fractional shortening was calculated from M-mode echocardiographic images by measuring left ventricular end diastolic dimension (LVEDD) and left ventricular end systolic dimension (LVESD) as follows: FS=LVEDD−LVESD]/LVEDD × 100. At specified time points following injury, the rodents were sacrificed and prepared for either fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or molecular or immunohistochemical analyses.

FACS Analysis

Murine bone marrow was extracted from the femur and tibia of eGFP mice (Jackson Labs; Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed, resuspended at 1.0 × 106 cells per milliliter in Hanks buffer containing 2% fetal calf serum, and stained with 5 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 (90 min at 37°C). Human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilized blood was obtained from bone marrow transplant donors by plasmapheresis. The plasmapheresis extract was diluted 1:5 in PBS and separated using Ficoll separation techniques. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed, resuspended at 1.0 × 106 cells per milliliter in X-Vivo 20 media and stained with 2.5 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 (90 min at 37°C). The cells were divided into two samples with one sample receiving fumitremorgin C (kindly provided by Lee Greenberger, Wyeth Research) at a concentration of 10 µM just prior to Hoechst 33342 staining [16, 18]. The cells were then counted and viability determined by trypan blue staining. Cellular viability was consistently above 95%. Murine cardiac tissue was harvested from eGFP mice following a transcardiac perfusion with ice-cold PBS. Tissue was then digested with pronase (10 mg/ml). Cell populations were then rinsed with PBS, pelleted, resuspended in Hanks media, and maintained at 4°C before FACS analysis. A MoFlo flow cytometer (Cytomation, Inc.) equipped with a 488-nm argon laser was used to detect the fluorescence of eEGFP and propidium iodide, respectively.

Transcriptome Analysis

Oligonucleotide array hybridizations were carried out according to the Affymetrix protocol as previously described [20–23]. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from eGFP FACS-sorted cells. Total RNA was isolated from the cell samples using the Tripure Isolation Kit (Roche). Two cycles of RNA amplification were performed for each sample. In the first cycle, double-stranded complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from total RNA using an oligo dT-T7 primer followed by an in vitro transcription reaction to produce primary complementary RNA (cRNA). Primary cRNA (200 ng) was then used for a second cycle of amplification. Following precipitation, the double-stranded cDNA was converted to biotin-labeled csRNA using the Enzo BioArray High-Yield RNA Transcript Labeling Kit (Enzo Biochem, New York, NY, USA). The purified biotin-labeled cRNA was then fragmented using Affymetrix fragmentation buffer for 35 min at 95°C. Labeled fragmented cRNA (15 µg) was then hybridized to the high-density oligonucleotide mouse array. After 6 h of hybridization, the array was washed, stained, and scanned according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The array data were analyzed using the MAS5.0 software package and Dchip to determine significant transcript expression and to determine common and unique expression profiles associated with the respective samples.

Immunohistochemistry

Hearts were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and hydrated with PBS as previously described [24]. Sections (5 µm in thickness) were permeabilized (0.3% triton in PBS for 5 min), blocked (5% normal goat serum/PBS for 30 min), and incubated at 4°C overnight with anti-alpha-sarcomeric actinin serum (1:150 dilution, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) or anti-human cardiac TnI serum (1:1,000 dilution, USBiological). The sections were then rinsed and incubated in lissaminerhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG serum (1:50; Jackson Immunoresearch). β-galactosidase expression was assessed using whole-mount and histological/histochemical techniques [22, 25]. Slides were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) evaluated using a Nikon TE2000-U inverted microscope (Nikon, Inc.) and a CoolSnap digital camera (Photometrics, Inc.) for the presence of DAPI-labeled nuclei.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

cDNA synthesis was performed using SuperScript II RT (Invitrogen) as previously described [22]. All primer pairs spanned an intron and the respective sequences are listed below:

Murine primers:

| Abcg2-For | GTGGCATCTCTGGAGGAGAA |

| Abcg2-Rev | TCCTGAGCTCCTGGAAGTTG |

| Tal1-For | ATGGAGATTTCTGATGGTCCTCAC |

| Tal1-Rev | AGTGTGCTTGGGTGTTGGCTC |

| Tnni3-For | GAAGGACCTGAATGAGCTACAGAC |

| Tnni3-Rev | GATCTTCTTCTTCTTCTCTCTCTCTGTC |

| Myh7-For | TAGAGGAGGCAGTACAGGAGTGTAG |

| Myh7-Rev | CTTCTTGTCTTCCTCTGTCGGGTAG |

| ATP Synth-For | GCCAACCTCATCTACTACTCCCTG |

| ATP Synth-Rev | TCCTGAGCTCCTGGAAGTTG |

Human-specific primers:

| ACTN2-For | AGCAGCAGTGGAGGTGAGTT |

| ACTN2-Rev | ATGGAGCAGGCCTTTAGACA |

| TNNI3-For | GTCCTCGGGGAGTCTCAAG |

| TNNI3-Rev | CGTTTGGAGGGTCAGTGAG |

| NKX 2.5-For | CCTCAACAGCTCCCTGACTC |

| NKX 2.5-Rev | TAGGTCTCCGCAGGAGTGAA |

| GATA-4-For | TCCTAGCCCTTGGTCAGATG |

| GATA-4-Rev | TTGCCTCCTGGACAAAAGAC |

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocol was as follows: 95°C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s.

Results

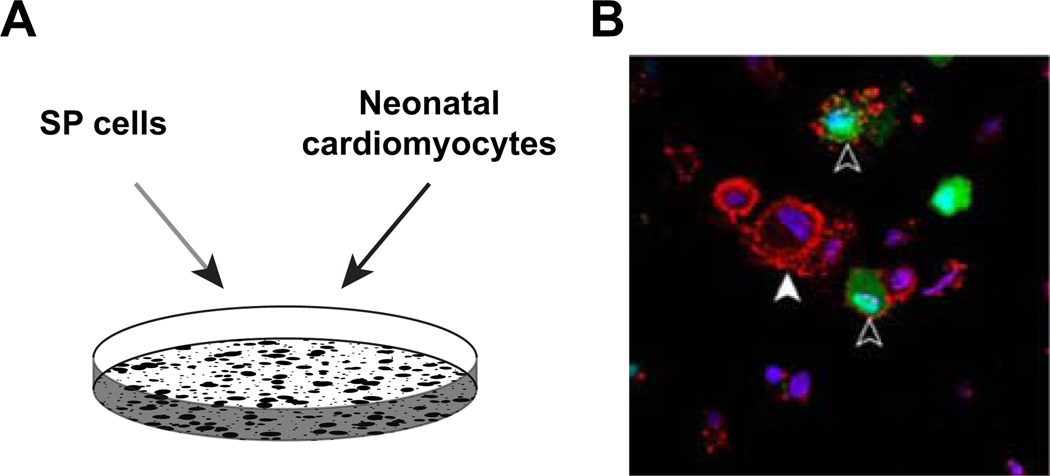

We have previously published that cardiac SP cells are capable of cardiac differentiation under co-culture conditions [16]. To examine the differentiation capacity of the bone marrow SP cell population, we co-cultured bone marrow SP cells isolated from the eGFP mouse with neonatal cardiomyocytes in media initially containing DAPI to label all nuclei. Following a 14-day co-culture period, the cell preparation was fixed and immunostained for alpha-actinin expression. As illustrated in Fig. 1B, a subpopulation of GFP-positive bone marrow SP cells following the co-culture period expressed alpha-actinin.

Fig. 1.

Bone marrow SP cells are capable of cardiac differentiation. A Bone marrow SP cells isolated from the GFP-expressing mouse were co-cultured with wild-type neonatal cardiomyocytes for a 14-day period. B Note that GFP-expressing (green) cells marked with black arrowhead express alpha-actinin (red). dapi-stained nuclei are apparent in all cells. White arrowhead marks non-GFP-expressing neonatal cardiomyocytes that also express alpha-actinin

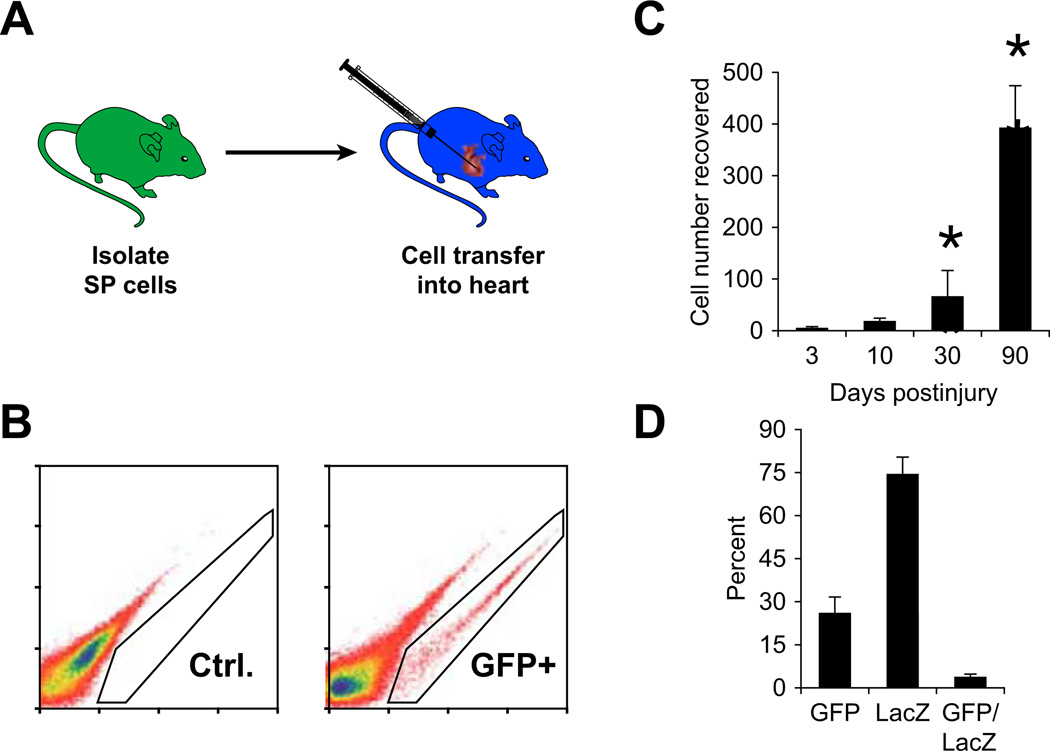

Having established that bone marrow SP cells were capable of expressing cardiac markers, we investigated their in vivo abilities. As schematized in Fig. 2A, 100,000 GFP-positive bone marrow SP cells were injected into the myocardium of immunocompromised mice immediately following myocardial injury. At specific time points, the hearts were harvested and analyzed with FACS. A percentage of GFP-positive cells were easily identified from the wild-type heart as shown in Fig. 2B. As expected, 3 days after injection, greater than 95% of the cells were destroyed (average number of cells recovered at day 3 = 3,867 ± 3,066, n = 3). However, over the following days, the percentage of cells that survived continued to proliferate up to 90 days after injection (average number cells recovered at day 30 = 41,000 ± 10,456, n = 4, p<0.05; day 90 = 331,667 ± 118,500, n = 3, p = 0.05; Fig. 2C). The presence of the GFP-positive cells was confirmed in sections of these hearts harvested 30 days after injury. Within the injured area, we identified a subpopulation of GFP-positive cells which had differentiated into small immature cardiomyocytes illustrated in Fig. 3A which co-express GFP and alpha-sarcomeric actinin. Importantly, this was only seen in a subpopulation of cells as there remained GFP-positive cells that did not express cardiac markers (Fig. 3B). To address the contribution of fusion, a separate experiment was performed. One hundred thousand GFP-positive bone marrow cells were injected into the myocardium of ROSA26 mice immediately after myocardial injury. Again, 30 days following injury and cell injection, the mice were sacrificed and hearts were harvested and sectioned. Beta-gal staining was performed and the sections were analyzed for LacZ-positive cells, GFP-positive cells, and LacZ/GFP-positive cells indicating fusion. We found that fusion occurred at a low frequency accounting for about 3% of the total cells (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Bone marrow SP cells delivered into the cryoinjured murine heart increase in number. A Experimental strategy used in these studies included isolation of GFP-labeled bone marrow SP cells using dual-wavelength FACS analysis. Following cryoinjury of an adult mouse heart, 100,000 GFP-labeled bone marrow SP cells were delivered (IM). B At defined periods, the adult mice that received the intramyocardial delivery of GFP-labeled BMSP cells were sacrificed and the hearts were evaluated for GFP-positive cells using FACS analysis. Left and right panels are representative FACS profiles from control (no cells) and experimental (received GFP-labeled cells) hearts, respectively. Note the absence of GFP-labeled cells in the left panel and presence of GFP-labeled cells in the right panel. C Quantification of GFP-labeled cells obtained by FACS analysis at defined time periods following myocardial injury/delivery. Note the statistically significant increase from day 3 to days 30 and 90 (p<0.05, n = 4). D At 30 days following myocardial injury and cell delivery into the ROSA adult mouse heart, the GFP-positive cells, LacZ-positive cells, and GFP/LacZ-positive cells indicating fusion were quantitated. Note that the double-positive cells account for only about 3% of total cells indicating a low incidence of cell fusion

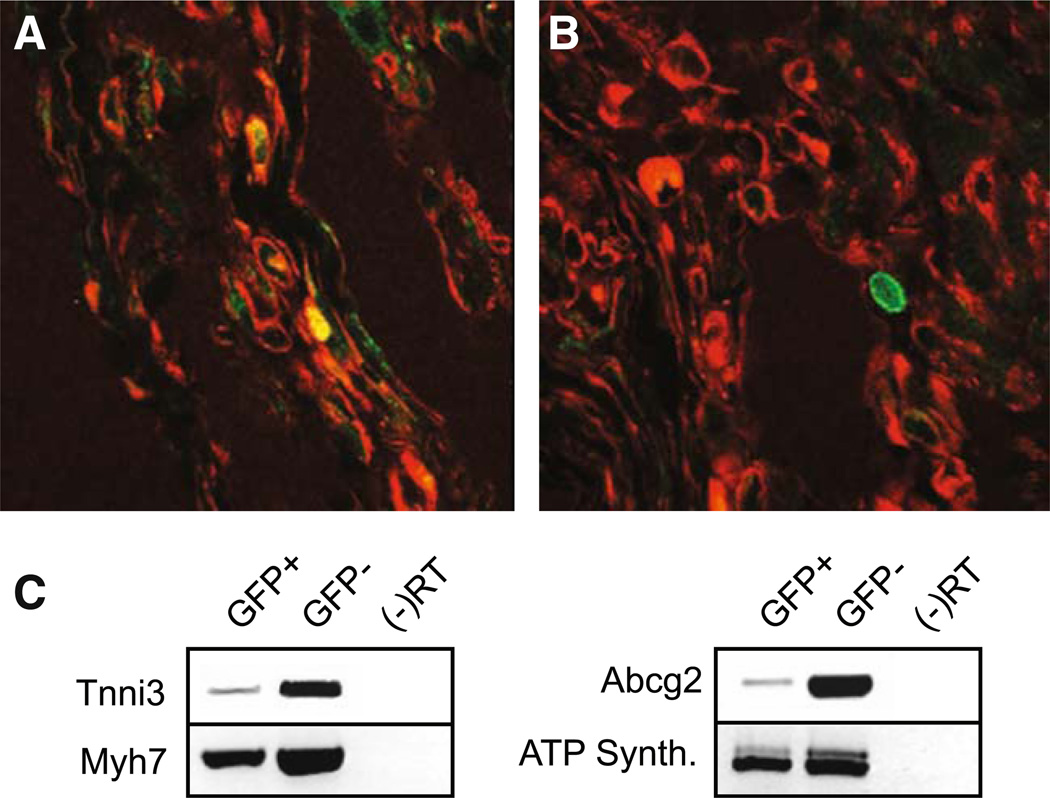

Fig. 3.

GFP-labeled bone marrow SP cells delivered into the injured myocardium express cardiac structural proteins. A Hearts analyzed 30 days after cryoinjury and intramyocardial delivery of GFP-labeled BMSP cells display co-localization of GFP-positive cells (green) and alpha-sarcomeric actinin (red) in a subpopulation of cells. B However, a second subpopulation of GFP-labeled BMSP cells lacked expression of cardiac structural proteins. C RT-PCR analysis of GFP-positive and GFP-negative cells recovered 30 days following myocardial injury/delivery show that the GFP-positive BM cells had increased expression of cardiac transcripts

We collected the GFP-positive cells 30 days following injury, and semi-quantitative PCR indicated that these cells expressed cardiac-specific markers; however, this expression was not as robust as seen in the mature differentiated GFP−cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3C). The GFP-positive cells have also lost expression of the hematopoetic marker Tal-1 (data not shown). Using transcriptome analysis, we further defined the genetic signature of the GFP+ cells recovered 30 days following injury cell compared to native BM SP cells and adult cardiomyocytes (Table 1). We observed that GFP+ cells recovered 30 days after injury showed a significant upregulation of structural cardiac proteins such as troponin and myoglobin and cardiac transcription factors including mef2c and gata4 when compared to native BM SP cells. The stem cell marker Abcg2 was downregulated, while continued expression of sca-1 and CD34 was noted. There was a loss of c-kit expression as well as expression of the hematopoetic cell surface markers CD45 and Tal-1. These cells appear to be immature cardiomyocytes as the level of the structural transcripts was significantly lower when compared to adult cardiomyocytes.

Table 1.

GFP-labeled bone marrow SP cells delivered into the injured myocardium express a cardiomyocyte molecular program

| Probe id | Gene title | Symbol | BMSP | Call | GFP+ | Call | ACM | Call | Call GFP+ / BMSP |

GFP+ / ACM |

BMSP / ACM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | |||||||||||

| 1448826_at | Myosin, heavy polypeptide 6, cardiac muscle, alpha | Myh6 | 45.60 | P | 1,021.80 | P | 20,331.90 | P | 12.13 | −27.86 | −477.71 |

| 1451203_at | Myoglobin | Mb | 13.60 | A | 337.30 | P | 19,109.50 | P | 32.00 | −45.25 | −1,782.89 |

| 1422536_at | Troponin I, cardiac | Tnni3 | 6.20 | A | 177.20 | A | 14,901.20 | P | 24.25 | −73.52 | −2,352.53 |

| 1418726_a_at | Troponin T2, cardiac | Tnnt2 | 1.80 | A | 1,499.60 | P | 19,317.30 | P | 168.90 | −16.00 | −10,809.41 |

| 1425028_a_at | Tropomyosin 2, beta | Tpm2 | 65.80 | A | 2,459.30 | P | 305.50 | P | 36.76 | 8.00 | −4.00 |

| 1427768_s_at | Myosin, light polypeptide 3, alkali; ventricular, skeletal, slow | Myl3 | 38.50 | A | 378.60 | P | 22,348.90 | P | 9.19 | −45.25 | −548.75 |

| 1448394_at | Myosin, light polypeptide 2, regulatory, cardiac, slow | Myl2 | 110.00 | A | 792.80 | P | 18,079.10 | P | 3.03 | −21.11 | −119.43 |

| 1415927_at | Actin, alpha, cardiac | Actc1 | 8.60 | A | 700.30 | P | 17,832.90 | P | 51.98 | −24.25 | −1,782.89 |

| Transcription factors | |||||||||||

| 1421027_a_at | Myocyte enhancer factor 2C | Mef2c | 60.00 | A | 831.50 | P | 511.90 | P | 17.15 | 1.32 | −8.57 |

| 1449566_at | NK2 transcription factor related, locus 5 (Drosophila) | Nkx2–5 | 61.80 | A | 115.80 | A | 649.00 | P | 1.62 | −4.29 | −6.06 |

| 1418863_at | GATA binding protein 4 | Gata4 | 39.50 | A | 102.40 | A | 520.30 | P | 2.30 | −5.66 | −9.85 |

| 1429177_x_at | SRY-box containing gene 17 | Sox17 | 18.90 | A | 1,152.00 | P | 1,177.60 | P | 68.59 | −1.07 | −68.59 |

| 1449135_at | SRY-box containing gene 18 | Sox18 | 31.40 | A | 1,717.50 | P | 746.50 | P | 39.40 | 2.46 | −17.15 |

| 1417447_at | Transcription factor 21 | Tcf21 | 45.20 | A | 1,124.00 | P | 173.90 | P | 27.86 | 6.96 | −3.48 |

| 1436041_at | Heart and neural crest derivatives expressed transcript 2 | Hand2 | 11.90 | A | 187.90 | A | 1,028.10 | P | 19.70 | −4.59 | −64.00 |

| 1423635_at | Bone morphogenetic protein 2 | Bmp2 | 46.00 | P | 243.10 | P | 43.30 | A | 6.06 | 6.50 | 1.15 |

| 1418517_at | Iroquois-related homeobox 3 (Drosophila) | Irx3 | 119.70 | A | 305.30 | P | 469.50 | P | 2.64 | −2.14 | −6.50 |

| Stem cell/cell surface markers | |||||||||||

| 1422906_at | ATP-binding cassette, sub- family G (WHITE), member 2 | Abcg2 | 1,544.50 | P | 896.20 | P | 618.60 | P | −2.46 | 1.23 | 3.25 |

| 1417185_at | Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus A (Sca-1) | Ly6a | 3,966.40 | P | 14,153.90 | P | 6,472.60 | P | 4.29 | 2.46 | −1.52 |

| 1416072_at | CD34 antigen | Cd34 | 683.00 | P | 2,113.20 | P | 1,118.90 | P | 3.48 | 2.30 | −1.62 |

| 1452514_a_at | Kit oncogene | Kit | 1,955.00 | P | 138.70 | A | 87.50 | A | −9.85 | 1.87 | 17.15 |

| 1422124_a_at | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, C (CD45) | Ptprc | 8,026.50 | P | 4,213.80 | P | 27.40 | A | −1.87 | 111.43 | 222.86 |

| 1449389_at | T cell acute lymphocytic leukemia 1 | Tal1 | 1,764.60 | P | 607.80 | P | 98.10 | A | −2.83 | 4.92 | 13.93 |

Thirty days following the delivery of 100,000 GFP-labeled bone marrow SP cells into the injured heart, GFP-labeled cells were isolated using FACS and the molecular program was analyzed using Affymetrix array technology. Note increased expression of cardiac-restricted genes in the GFP-labeled cells suggesting that the bone marrow SP cells are capable of cardiac differentiation.

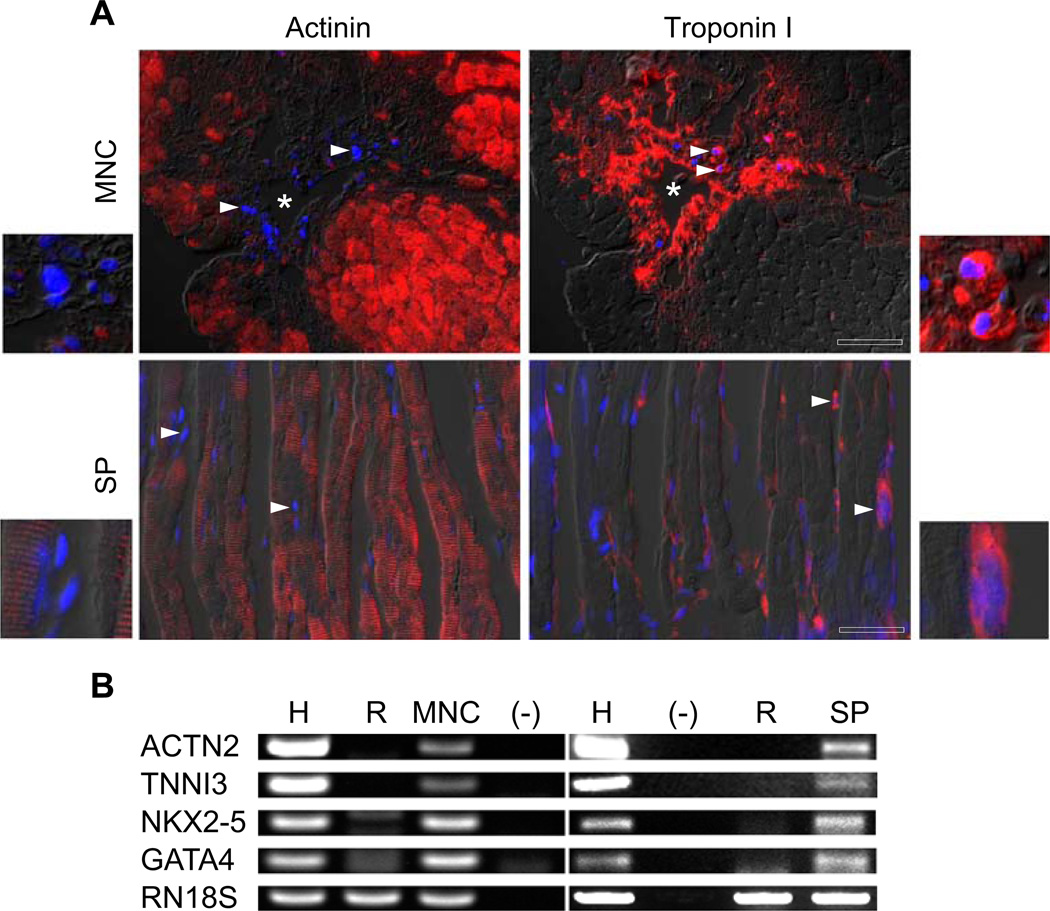

These studies suggest that these cells acquire a cardiac fate but are arrested in differentiation compared to fully functional cardiomyocytes. Having established that murine bone marrow SP possessed the ability to differentiate to a cardiac lineage, we examined the capability of similar human stem cell populations. GSF-stimulated peripheral blood SP cells and MNCs were injected into the myocardium of immunocompromised rats following myocardial injury. At 30 days, the hearts were harvested and analyzed. DAPI-positive cells were identified in both SP- and MNC-treated groups. It is important to note that, while the MNCs were found in clusters closely related to the needle track (marked as an asterisk), the SP cells displayed a more diffuse organization within the injured myocardium (Fig. 4A). Immunohistochemical evaluation was carried out using human-specific cardiac troponin I primary antibody as well as rat-specific alpha-actinin primary antibody to rule out the possibility of fusion (Fig. 4A). The results indicate that the DAPI-labeled human cells, both MNCs and SP cells, expressed human troponin I, while the rat-specific alpha-actinin was expressed solely by the adjacent rat myocardium. Note the discrepancy in cellular distribution between the MNCs and the SP cells with the SP cells arranged more diffusely. Even in areas with normal rat myocardium, the expression of human troponin I was always associated with DAPI-positive SP cells. PCR analysis of cDNA isolated from the anterior left ventricular wall of athymic nude rats using human-specific cardiac primers confirmed the presence of human cardiac transcripts in the hearts treated with human cells (both MNCs and SP cells; Fig. 4B). None of the human transcripts were found in the control (media-injected) hearts. These results provide further support that both human cell populations (MNCs and SP cells) are capable of acquiring a cardiac fate within the injured myocardium.

Fig. 4.

Both MNC and SP cells express human-specific cardiac markers within the rat myocardium. A Immunohistochemical staining of DAPI-labeled human MNC and SP cells within the cryoinjured rat myocardium. The two upper panels show human DAPI-labeled MNC within the rat myocardium 1 month following cryoinjury stained with rat-specific α-actinin (upper left) and human-specific troponin I (upper right). The asterisk marks the needle track through which the injections were performed (scale bar = 25 µm). The two lower panels show human DAPI-labeled SP cells within the rat myocardium 1 month following cryoinjury stained with rat-specific α-actinin (lower left) and human-specific troponin I (lower right; scale bar = 20 µm sera.). Note that the rat-specific α-actinin staining in all the panels colocalizes with the rat myocardium but not the DAPI-labeled human cells and that the human-specific troponin I staining is localized to the DAPI-positive human cells. The arrowheads point to representative human nuclei. The insets are high magnifications of representative cells from each of the four panels, respectively. B RT-PCR analysis (using human-specific cardiac primers) of rodent hearts that received human MNCs, human SP cells, or media as it compared to human heart controls. Note that hearts that received either MNCs or SP cells contained easily detectable levels of human cardiac transcripts

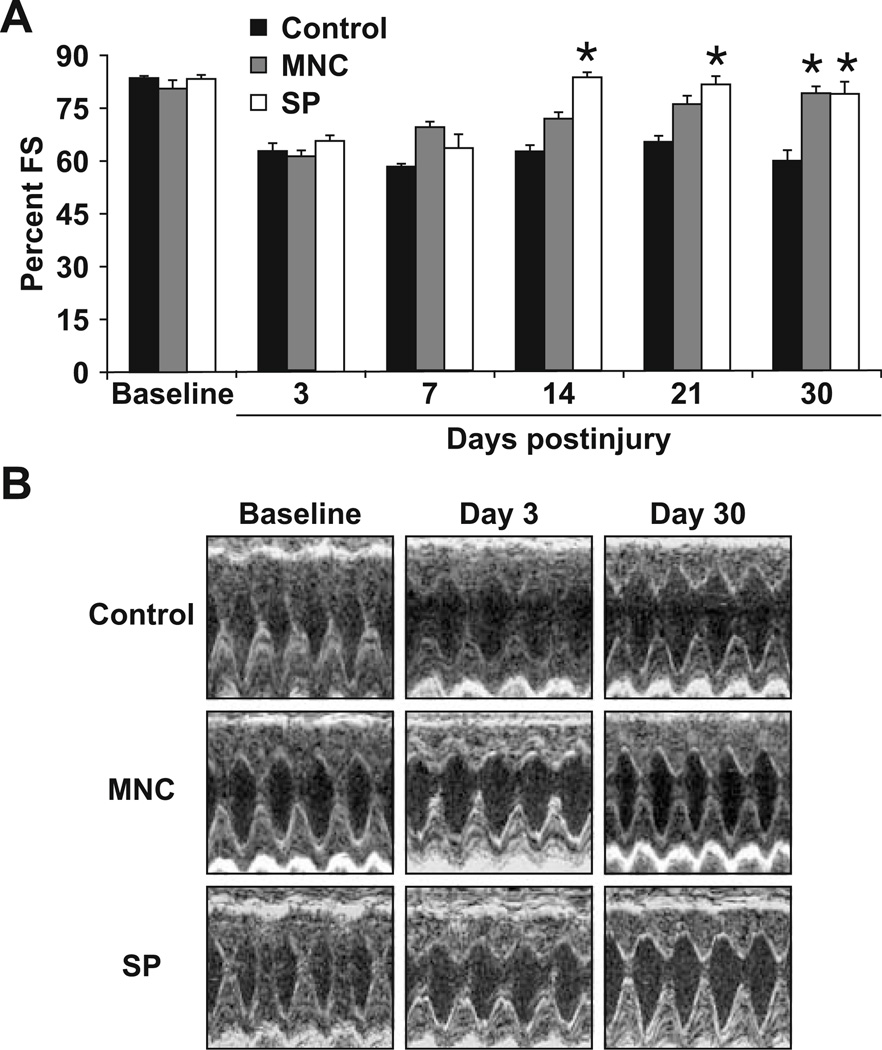

Echocardiographic evaluation at 3 days postinjury demonstrated a significant decline in FS of about 15–20% in all animals (Fig. 5A, B). Serial echocardiographic evaluations revealed normalization of LV FS in the SP group by 14 days (n = 4, p<0.001 compared to both media control and MNC groups, p = NS compared to preinjury FS). This improvement persisted to the conclusion of the study. The MNC-treated group displayed a gradual improvement in LV FS over the study period and normalization of FS by 30 days (p<0.001 compared to media control and p = NS compared to SP group and preinjury FS). In contrast, the control group (injected with media alone) did not show any improvement in FS over the entire study duration. These results indicate that the hearts that were injected with the human SP cells normalized their FS 2 weeks earlier than those that received the MNCs. This occurred despite the fact that the cell count was ten times higher in the MNC group compared to the SP group (9 × 105 cells per heart in the MNC group compared to 9 × 104 per heart in the SP group).

Fig. 5.

Echocardiographic evaluation of left ventricular systolic function following cryoinjury. A Fractional shortening control (media-injected) and mononuclear-cell-injected (MNC) and SP-cellinjected hearts. Note the significant improvement (p<0.001, n = 4) in the fractional shortening of hearts injected with SP cells by 14 days postinjury and the delayed improvement in fractional shortening of the hearts injected with MNC despite the significantly larger number of MNC injected (9 × 104 SP cells vs. 9 × 105 MNC). Also note the lack of improvement in fractional shortening of control hearts injected with media alone. B Representative M-mode echocardiographic images of control, MNC, and SP cell groups

Discussion

Our group and several others have demonstrated that resident cardiac SP cells are activated upon myocardial injury and contribute to new cardiomyocyte formation [26, 27]. However, despite the robust stem cell characteristics displayed by cardiac SP cells and other resident cardiac stem cell populations expressing C-kit or Sca-1 markers [28, 29], the adult heart remains incapable of complete regeneration following injury. Therefore, intense interest has focused on “supplementing” the injured myocardium with extracardiac stem cells to promote regeneration.

The use of bone-marrow-derived stem cells for myocardial repair is already being promoted as a therapeutic option based on positive clinical trial outcomes [1–8]. The most widely used bone-marrow-derived population is the MNC population because of the relative ease of obtaining autologous cells with minimal processing [9, 10]. This heterogeneous population of cells contains both stem and non-stem-cell populations with the potential of differentiating into multiple lineages such as cardiac, endothelial, and smooth muscle lineages [30–32]. It is therefore important to determine the differentiation potential of each stem cell type and the role of using specific stem cell populations as compared to the whole MNC fraction.

In the current study, we provide multiple levels of evidence that bone-marrow-derived SP cells contribute to myocardial regeneration following injury. First, we show that murine BM-derived SP cells express cardiac markers following co-culture with neonatal cardiomyocytes. Second, we demonstrate that murine BM-derived SP cells not only survive but also increase in number following injection into the cryoinjured myocardium. Third, the murine BM-derived SP cells express numerous cardiac-restricted markers and microarray analysis reveals a significant change in their genetic signature from the hematopoietic pattern of native bone marrow to a signature more consistent with immature cardiomyocytes seen in the GFP-positive cells recovered 30 days after injury. Fourth, we demonstrate that human BM-derived SP cells survive within the injured rodent myocardium for the study duration and are more efficient at restoring the left ventricular systolic function than MNCs. Finally, both human cell types (MNC and SP cells) expressed human-specific cardiac-restricted markers by immunohistochemistry and PCR within the rat myocardium with no evidence of fusion with rat cardiomyocytes. Based on these results, we conclude that bone-marrow-derived SP cells have potential for use in myocardial regenerative therapies and are more efficient when compared to unfractionated MNCs.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance provided by Maggie Robeldo, Caroline Humphries, Sean Goetsch, and Nan Jiang.

Sources of Funding Funding was provided by the GlaxoSmithKline (CMM), American Heart Association (DJG, HAS), and March of Dimes Associations (DJG).

Footnotes

Disclosures None

Contributor Information

Hesham A. Sadek, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

Cindy M. Martin, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA Lillehei Heart Institute, University of Minnesota, 312 Church St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

Shuaib S. Latif, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

Mary G. Garry, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA Lillehei Heart Institute, University of Minnesota, 312 Church St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

Daniel J. Garry, Email: garry@umn.edu, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA; Lillehei Heart Institute, University of Minnesota, 312 Church St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

Reference

- 1.Assmus B, et al. Transcoronary transplantation of progenitor cells after myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(12):1222–1232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ince H, et al. Prevention of left ventricular remodeling with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after acute myocardial infarction: final 1-year results of the Front-Integrated Revascularization and Stem Cell Liberation in Evolving Acute Myocardial Infarction by Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (FIRST-LINE-AMI) Trial. Circulation. 2005;112(9 Suppl):I73–I80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janssens S, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem-cell transfer in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9505):113–121. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang HJ, et al. Differential effect of intracoronary infusion of mobilized peripheral blood stem cells by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on left ventricular function and remodeling in patients with acute myocardial infarction versus old myocardial infarction: the MAGIC Cell-3-DES randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2006;114(1 Suppl):I145–I151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunde K, et al. Intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(12):1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer GP, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: eighteen months' follow-up data from the randomized, controlled BOOST (BOne marrOw transfer to enhance ST-elevation infarct regeneration) trial. Circulation. 2006;113(10):1287–1294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.575118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schachinger V, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(12):1210–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wollert KC, et al. Intracoronary autologous bone-marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: The BOOST randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9429):141–148. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menasche P. Cellular therapy in thoracic and cardiovascular disease. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2007;84(1):339–342. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle AJ, et al. Is stem cell therapy ready for patients? Stem Cell Therapy for Cardiac Repair. Ready for the Next Step. Circulation. 2006;114(4):339–352. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser AR, et al. Immature monocytes from G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood stem cell collections carry surface-bound IL-10 and have the potential to modulate alloreactivity. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2006;80(4):862–869. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodell MA, et al. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1996;183(4):1797–1806. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodell MA, et al. Dye efflux studies suggest that hematopoietic stem cells expressing low or undetectable levels of CD34 antigen exist in multiple species. Natural Medicines. 1997;3(12):1337–1345. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gussoni E, et al. Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse restored by stem cell transplantation. Nature. 1999;401(6751):390–394. doi: 10.1038/43919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson KA, Mi T, Goodell MA. Hematopoietic potential of stem cells isolated from murine skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(25):14482–14486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin CM, et al. Persistent expression of the ATP-binding cassette transporter, Abcg2, identifies cardiac SP cells in the developing and adult heart. Developmental Biology. 2004;265(1):262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bunting KD. ABC transporters as phenotypic markers and functional regulators of stem cells. Stem Cells. 2002;20(1):11–20. doi: 10.1002/stem.200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scharenberg CW, Harkey MA, Torok-Storb B. The ABCG2 transporter is an efficient Hoechst 33342 efflux pump and is preferentially expressed by immature human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 2002;99(2):507–512. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molkentin JD, et al. A calcineurin-dependent transcriptional pathway for cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 1998;93(2):215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81573-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naseem RH, et al. Reparative myocardial mechanisms in adult C57BL/6 and MRL mice following injury. Physiological Genomics. 2007;30:44–52. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00070.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallardo TD, Hammer RE, Garry DJ. RNA amplification and transcriptional profiling for analysis of stem cell populations. Genesis. 2003;37(2):57–63. doi: 10.1002/gene.10223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masino AM, et al. Transcriptional regulation of cardiac progenitor cell populations. Circulation Research. 2004;95(4):389–397. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000138302.02691.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goetsch SC, et al. Transcriptional profiling and regulation of the extracellular matrix during muscle regeneration. Physiological Genomics. 2003;14(3):261–271. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00056.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garry DJ, et al. Persistent expression of MNF identifies myogenic stem cells in postnatal muscles. Developmental Biology. 1997;188(2):280–294. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng TC, et al. Separable regulatory elements governing myogenin transcription in mouse embryogenesis. Science. 1993;261(5118):215–218. doi: 10.1126/science.8392225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin CM, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha transactivates Abcg2 and promotes cytoprotection in cardiac side population cells. Circulation Research. 2008;102(9):1075–1081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfister O, et al. CD31− but Not CD31+ cardiac side population cells exhibit functional cardiomyogenic differentiation. Circulation Research. 2005;97(1):52–61. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000173297.53793.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beltrami AP, et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114(6):763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuura K, et al. Adult cardiac Sca-1-positive cells differentiate into beating cardiomyocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(12):11384–11391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310822200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bittner RE, et al. Recruitment of bone-marrow-derived cells by skeletal and cardiac muscle in adult dystrophic mdx mice. Anatomy and Embryology (Berl) 1999;199(5):391–396. doi: 10.1007/s004290050237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson KA, et al. Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107(11):1395–1402. doi: 10.1172/JCI12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orlic D, et al. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410(6829):701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]