Abstract

Background

The “four core genotypes” (FCG) mouse model has emerged as a major model testing if sex differences in phenotypes are caused by sex chromosome complement (XX vs. XY) or gonadal hormones or both. The model involves deletion of the testis-determining gene Sry from the Y chromosome and insertion of an Sry transgene onto an autosome. It produces XX and XY mice with testes, and XX and XY mice with ovaries, so that XX and XY mice with the same type of gonad can be compared to assess phenotypic effects of sex chromosome complement in cells and tissues.

Findings

We used PCR to amplify the Sry transgene and adjacent genomic sequences, to resolve the location of the Sry transgene to chromosome 3 and confirmed this location by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) of the Sry construct to metaphase chromosomes. Using quantitative PCR, we estimate that 12–14 copies of the transgene were inserted. The anogenital distance (AGD) of FCG pups at 27–29 days after birth was not different in XX vs. XY males, or XX vs. XY females, suggesting that differences between XX and XY mice with the same type of gonad are not caused by difference in prenatal androgen levels.

Conclusion

The Sry transgene in FCG mice is present in multiple copies at one locus on chromosome 3, which does not interrupt known genes. XX and XY mice with the same type of gonad do not show evidence of different androgen levels prenatally.

Keywords: Four core genotypes, Sex chromosome, Sry, Mouse, Vectorette PCR, Inverted PCR, Anogenital distance, Transgene, Fluorescence in situ hybridization, Integration site

The four core genotypes (FCG) mouse model has the advantage of separating two major factors that cause phenotypic sex differences: sex chromosome complement (XX vs. XY) and gonadal hormones [1-10]. The FCG model was established by combining two mutations in the same mouse line: deletion of the Sry gene from the Y chromosome (producing the Y− chromosome), and insertion of an Sry transgene onto an autosome [11,12]. Four genotypes are produced: XX mice with and without the Sry transgene, (XXSry, XX), and XY− mice with and without the Sry transgene (XY−Sry, XY−). Comparing XX and XY mice of the same gonadal type allows the measurement of the effect of sex chromosome complement (XX vs. XY) on traits in a similar hormonal environment. The Sry transgene has been used in over 60 primary literature articles (Table 1), and the FCG model is available commercially (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor ME, strain 010905, B6.Cg-Tg(Sry)2Ei Sry < dl1Rlb>/ArnoJ). Here we report the location and number of copies of the Sry transgene.

Table 1.

Publications using the Sry transgene

| Authors and years | Authors and years |

|---|---|

| Abel et al., 2011 [13] | Markham et al., 2003 [14] |

| Barker et al., 2010 [15] | Mazeyrat et al., 2001 [16] |

| Bonthius et al., 2012 [17] | McPhie-Lalmansingh et al., 2008 [18] |

| Burgoyne et al., 2002 [19] | Moore et al., 2013 [20] |

| Caeiro et al., 2011 [21] | Ngun et al., 2014 [22] |

| Carruth et al., 2002 [23] | Palaszynski et al., 2005 [24] |

| Chen et al., 2008, 2009, 2012, 2013a, 2013b [25-29] | Park et al., 2008 [30] |

| Cocquet et al., 2009 [31] | Quinn et al., 2007 [32] |

| Corre et al., 2014 [33] | Reynard et al., 2009 [34] |

| Cox and Rissman, 2011 [35] | Robinson et al., 2011 [36] |

| Dadam et al., 2014 [37] | Sasidhar et al., 2012 [38] |

| De Vries et al., 2002 [1] | Scerbo et al., 2014 [39] |

| Durcova-Hills et al., 2004 [40] | Seney et al., 2013a, 2013b [41,42] |

| Ehlen et al., 2013 [43] | Seu et al., 2014 [44] |

| Ellis et al., 2005 [45] | Smith-Bouvier et al., 2008 [46] |

| Gatewood et al., 2006 [47] | Szot et al., 2003 [48] |

| Gioiosa et al., 2008a, 2008b [49,50] | Toure et al., 2004, 2005 [51,52] |

| Ishikawa et al., 2003 [53] | Van Nas et al., 2009 [54] |

| Ji et al., 2010 [55] | Vernet et al., 2011, 2012 [56,57] |

| Kopsida et al., 2013 [58] | Wagner et al., 2004 [59] |

| Kuljis et al., 2013 [60] | Ward and Burgoyne, 2006 [61] |

| Kuo et al., 2010 [62] | Wijchers et al., 2010 [63] |

| Li et al., 2014 [64] | Xu and Arnold, 2005 [65] |

| Liu et al., 2010 [66] | Xu et al., 2002, 2005a, 2005b, 2006, 2008a, 2008b [67-72] |

| Mahadevaiah et al., 1998 [12] | Yamauchi et al., 2010 [73] |

| Manwani et al., 2015 [74] |

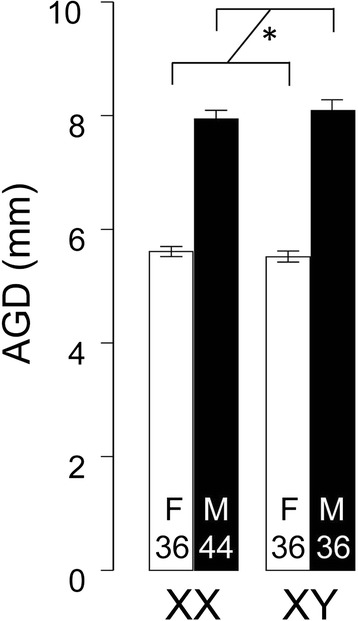

An important issue is whether XX and XY FCG mice with the same type of gonad experience different levels of gonadal hormones, which therefore might confound the effects of sex chromosome complement (XX vs. XY). Previous studies have not detected differences in the levels of testosterone in XX vs. XY adult males, or in estradiol in XX vs. XY females groups [33,38,47,74]; R. Schafer, personal communication), but possible differences in levels of prenatal hormones have not been assessed. Here we measured anogenital distance postnatally. Because androgens secreted prenatally by the testes cause the AGD to be larger in mice with testes than in those with ovaries [75,76], AGD is considered an excellent bioassay for the prenatal levels of androgens. These effects of androgens cause permanent sex differences in AGD, and are classified as “organizational” effects of gonadal hormones.

Methods

To identify the Sry transgene location, we first screened the DNA sequences flanking the transgene using inverted PCR [77] and vectorette PCR [78]. Amplified PCR fragments of the boundaries were sequenced, and their specificities were confirmed by PCR using 6 and 10 pairs of transgene-specific and flanking region primers on each end, using DNA from C57BL/6 FCG mice as templates. PCR was carried out with MyTaq HS Red Mix (Bioline USA Inc.). The PCR reaction started at 94°C for 4 min before the cycling reaction of 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 sec/60°C for 30 sec/72°C for 1 min, and then followed by single reaction at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR reaction mixture was separated by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis in 1 x TAE at 80 V. The primers used in Figure 1 were: a) 5′-CCA TCT GGC CTA TGA TGG AT-3′ (chr 3), b) 5′-CCT GCA GAC ATT CTC TGT GC-3′ (chr 3), c) 5′-GCA AAG CTG AAC AAG CAA CA-3′ (Sry transgene). d) 5′-CCA GGA CCA GGC AAT TAT GT-3′ (Sry transgene), e) 5′-TAA ATG GAG GGA AGC TGG AA-3′ (chr 3). Boundary DNA sequences are deposited in Genbank (accession: KF959637).

Figure 1.

Location of the Sry transgene in four core genotypes mouse model. Samples were from XX and XY mice with testes (XXSry, XY− Sry) and XX and XY mice with ovaries (XX, XY−). Confirmation of transgene-genome boundary by PCR using transgene-specific primer d and Chr3 primer e (A) , with transgene-specific primer c and Chr3 primer b (B), and with transgene-specific primer c and Chr3 primer a (C). (D) The concatemer of Sry transgene is inserted into a repetitive sequence present genome-wide. (E) Sry transgene location on chromosome 3. (F) A visual estimate of the difference in copy number of Sry between wildtype and XY− Sry genomic DNA in agarose gel.

To estimate the number of Sry copies integrated in the insertion site, we used quantitative PCR (standard curve method) to amplify Sry transgenes from genomic DNA. The quantitative PCR primers for Sry and control beta-2 microglobulin (B2m) were: Sry (5′-TTC CAG GAG GCA CAG AGA TT-3′, 5′-GCA GGC TGT AAA ATG CCA CT-3′), B2m (5′-AGG CCA AAA GCT CAC TCA AA-3′, 5′-GTG AGT TCT GGC TCC ACC AT-3′). We also confirmed the FCG vs. WT difference in copy number non-quantitatively and visually on agarose gels with PCR using other primers: Sry (5′- AGC CCT ACA GCC ACA TGA TA-3′, 5′- GTC TTG CCT GTA TGT GAT GG-3′), myogenin (5′- TTA CGT CCA TCG TGG ACA GCA T-3′, 5′- TGG GCT GGG TGT TAG TCT TAT-3′).

To evaluate the influence of the Sry transgene on genes in the vicinity of the transgene, we analyzed the FCG and WT liver microarray expression datasets (GSE13264, GSE13265) [54]. Those comparable datasets were from C57BL/6J background, using the same microarray platform in the same lab. One dataset allows measuring changes in gene expression caused by the Sry transgene in gonadectomized FCG mice (using a 2-way ANOVA with factors of sex chromosome complement (XX vs. XY) and Sry transgene (present vs. absent). The other dataset compares gonadectomized WT males and females, allowing measurement of the effects of the endogenous Sry gene on the Y chromosome (one-way ANOVA). The strain origin of the Y chromosome differed in the two datasets. We report both the p-values of the ANOVAs (non-stringent analysis without correction for multiple testing), as well as more conservative False Discovery Rate p-values [79] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Expression of Chr3 genes near the Sry transgene

| FCG | WT | Distance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probe | ANOVA | FDR | MF | ANOVA | FDR | MF | (bp) |

| Lxn | 0.001 | 0.035 | -0.08 | 0.549 | 0.998 | 0.02 | -3215751 |

| Rarres1 | 0.868 | 0.963 | -0.01 | 0.678 | 0.999 | -0.02 | -3194863 |

| Mfsd1 | 0.187 | 0.530 | -0.04 | 0.339 | 0.951 | -0.05 | -3090981 |

| Schip1 | 0.033 | 0.225 | -0.04 | 0.806 | 0.999 | -0.01 | -2608947 |

| Schip1 | 0.568 | 0.837 | -0.01 | 0.615 | 0.999 | -2608947 | |

| Il12a | 0.310 | 0.656 | -0.01 | 0.598 | 0.999 | 0.01 | -1983105 |

| Trim59 | 0.021 | 0.179 | -0.09 | 0.160 | 0.832 | 0.03 | -1638461 |

| Trim59 | 0.950 | 0.985 | 0.00 | 0.623 | 0.999 | 0.02 | -1638461 |

| Kpna4 | 0.868 | 0.963 | 0.00 | 0.760 | 0.999 | -0.01 | -1606600 |

| Ppm1l | 0.034 | 0.230 | 0.08 | 0.002 | 0.417 | 0.06 | -1356888 |

| Nmd3 | 0.085 | 0.362 | 0.07 | 0.083 | 0.734 | 0.10 | -951764 |

| Sry transgene | 0 | ||||||

| Slitrk3 | 0.346 | 0.684 | -0.02 | 0.728 | 0.999 | 0.02 | 2374377 |

| Bche | 0.060 | 0.306 | 0.10 | 0.931 | 0.999 | -0.01 | 2962059 |

| Serpini2 | 0.676 | 0.890 | 0.01 | 0.942 | 0.999 | 0.00 | 4568621 |

| Pdcd10 | 0.231 | 0.580 | 0.03 | 0.308 | 0.938 | 0.04 | 4842741 |

| Pdcd10 | 0.336 | 0.677 | 0.02 | 0.278 | 0.926 | 0.04 | 4842741 |

| Serpini1 | 0.130 | 0.447 | 0.01 | 0.509 | 0.993 | -0.02 | 4883798 |

| Fstl5 | 0.917 | 0.978 | 0.00 | 0.831 | 0.999 | 0.01 | 5400521 |

| Rapgef2 | 0.900 | 0.973 | 0.00 | 0.319 | 0.946 | 0.03 | 8388767 |

| Ppid | 0.002 | 0.056 | 0.14 | 0.674 | 0.999 | 0.02 | 8917593 |

| Etfdh | 0.024 | 0.191 | 0.09 | 0.987 | 0.999 | 0.00 | 8930039 |

| 4930579G24Rik | 0.658 | 0.880 | 0.02 | 0.118 | 0.776 | -0.07 | 8955330 |

The table shows ANOVA and False Discovery Rate (FDR) p-values of Sry effects on gene expression in liver of FCG mice (effect of Sry transgene) and of WT mice (effect of endogenous Sry). For several genes, p values for two different probes for the same gene are shown. MF is fractional mean difference between males (M, with Sry) and females (F, without Sry). For example, -0.08 means that F had about 8% higher expression than M. Distance is relative to the Sry transgene in FCG mice.

Metaphase chromosome spreads for FISH analysis were prepared from primary fibroblast cells cultured from tail tips. The Sry transgene plasmid construct was labeled with AF555 dUTP by nick-translation and hybridization was performed at 37°C in a humid chamber for 18–20 hours in the presence of 10 ug mouse Cot1 DNA (Invitrogen) and 9.4 mg salmon sperm DNA in Hybrisol VII (MP Biomedicals). Post-hybridization washes were 1× 2 minutes 2XSSC/0.3% NP40 at 68°C, 1 × 2 minutes 2XSSC/0.1% NP40 at 25°C. Images were captured using an Olympus AX-71 equipped with the Genus imaging software (Leica). For chromosome 3 (Chr3) painting, biotin-labeled Chromosome 3 Star*FISH© paint (Cambio) was used with the addition of a pre-annealing step prior to hybridization at 37°C for 90 minutes, followed by signal detection with fluoresceinated avidin.

Anogenital distance was measured in 34–44 C57BL/6 J FCG mouse pups per genotype, at 27–29 days after birth, using a caliper. A two-way ANOVA (factors of sex chromosome complement, XX vs. XY, and Sry (present vs. absent) was used to assess group differences. The investigator was blind to the genotype. Genotypes of FCG mice was determined by standard PCR genotyping methods using the primers: Sry (5′-AGC CCT ACA GCC ACA TGA TA-3′, 5′-GTC TTG CCT GTA TGT GAT GG-3′), Ymt (Y chromosome-specific sequence, 5′-CTG GAG CTC TAC AGT GAT GA-3′, 5′-CAG TTA CCA ATC AAC ACA TCA C-3′), and myogenin (5′-TTA CGT CCA TCG TGG ACA GCA T-3′, 5′-TGG GCT GGG TGT TAG TCT TAT-3′).

Findings

The inverted PCR and vectorette PCR methods indicated that DNA sequences flanking the transgene represent part of a repetitive motif that is found at 210–388 genomic locations (http://www.ensembl.org, Release 73). Figure 1A and B show the transgene-specific PCR amplification between Sry transgene sequence and the surrounding repetitive sequence. These were not informative for mapping the transgene in the genome, but some DNA fragments from vectorette PCR suggested that the transgene was integrated into the motif within Chr3. This conclusion was confirmed by amplification with Chr3-specific primer a and transgene-specific primer c (Figure 1C and D). The Sry transgene integration site was at Chr3 70673749-70673824 bp (Figure 1E, based on Ensembl Release 73), and involved deletion of 74 bp of Chr3 during integration. The integration did not interrupt any known protein coding genes or pseudogenes (Table 3). The gene closest to the integration site is the Gm10780 pseudogene, 15 kb distant from the transgene.

Table 3.

Chr3 genes near the Sry transgene

| Ensembl gene ID | Start (bp) | End (bp) | Gene name |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENSMUSG00000087848 | 69685467 | 69685580 | Gm25621 |

| ENSMUSG00000068969 | 69716986 | 69717393 | Rpl32-ps |

| ENSMUSG00000027787 | 69721985 | 69749042 | Nmd3 |

| ENSMUSG00000043461 | 69819538 | 69859896 | Sptssb |

| ENSMUSG00000077366 | 69962315 | 69962445 | Gm23484 |

| ENSMUSG00000027788 | 70007613 | 70028708 | Otol1 |

| ENSMUSG00000089507 | 70228747 | 70228874 | Gm23477 |

| 70673749 | 70673824 | (Sry transgene) | |

| ENSMUSG00000074877 | 70689092 | 70689380 | Gm10780 |

| ENSMUSG00000097252 | 70772379 | 70807291 | AC105155.1 |

To assess if the transgene affected gene expression nearby, we compared expression of 22 probes in liver in FCG mice with and without the transgene (Table 2). Most nearby genes showed no effect of the transgene. In a few cases, expression was affected by Sry, which could have been a local effect or one mediated by testicular secretions downstream of Sry. To control for hormonally-induced changes in gene expression, we compared expression of the same genes in WT males (with endogenous Sry) vs. females using published microarray gene profiling. Two genes, Lxn and Ppid, show evidence of regulation by the Sry transgene but not by WT Sry, based on conservative analysis. These are about 3 megabases or more from the transgene. Based on less stringent analysis, several other genes are candidates for those differentially expressed by the transgene vs. WT Sry. Further work is needed to determine if the transgene effects are found in different tissues and conditions, and are direct or indirect.

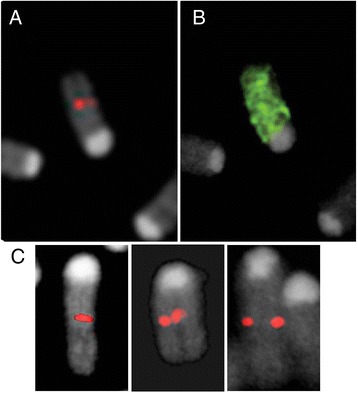

The Sry transgene band in genomic DNA from FCG was stronger than in WT (Figure 1F), suggesting that the transgene was concatemerized during integration at this site. The number of copies of the transgene was estimated with quantitative genomic PCR (not shown) to be 12–14. The Sry transgene probe was co-localized with the Chr3 paint in metaphase spreads from FCG mice (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

FISH mapping of the Sry transgene to Chromosome 3. The Sry transgene signal (A, red) and chromosome Chromosome 3 paint (B, green) hybridize to the same metaphase chromosome. (C) Sry transgene hybridization in three additional metaphase cells demonstrating its location with respect to the p- and q-arm ends.

AGD was found to differ in mice with testes vs. ovaries (Figure 3), but not in XX and XY mice of the same gonadal sex (Figure 3). A two-way ANOVA showed a significant main effect of sex (F(1,146) = 223, p < 0.00001), but no effect of sex chromosome complement (XX vs. XY, F(1,146) = 0.03, p = 0.87) and no significant interaction (F(1,146) = 0.67, p = 0.42).

Figure 3.

Anogenital distance measurement of FCG mice. Asterisk shows the significant effect of sex (two way ANOVA, p < 0.00001).

Discussion

The goal of transgenic insertion is to achieve normal levels of expression of the transgene without influencing other genes because of interruption of coding or regulatory regions in the genome. Transgenic models are often useful even when this goal is not achieved in every respect. In the FCG model, mice with Sry are similar to WT males in numerous traits, but differ for a few other traits, including higher expression of Sry, indicating that the transgene effect is similar but not identical to endogenous Sry [1,74]. Here we show that insertion of Sry onto Chr3 does not disrupt any known coding sequence. Moreover, analysis of gene expression suggests that two genes near Sry may also be altered by the transgenic insertion, as judged by expression levels in liver. Further analysis is required to determine if local genes are affected by the transgene. The FCG model has the advantage of comparing the effects of sex chromosome complement (XX vs. XY) in mice with and without the transgene. The FCG model has been useful for discovering numerous traits that are influenced by sex chromosome complement, which are independent of the presence of the transgene or have been confirmed by analysis of non-transgenic mouse models that vary sex chromosome complement [25-28,64,80]. The concatemeric insertion of 12–14 copies of a transgene at one site is not unexpected, and in the present case is associated with higher than normal expression of Sry in FCG than WT mice [74].

The greater AGD in mice with testes is expected from previous studies that demonstrate that AGD is influenced by the level of prenatal androgens. The present data offer no support for the hypothesis that the levels of androgens secreted prenatally, when AGD is determined, differ in XX and XY mice with the same type of gonad. For example, there was no masculinization of AGD of XY females relative to XX females. That result argues against the idea that XX vs. XY differences observed in numerous tissues are a result of differences in levels of prenatal androgens.

The present results contribute to the understanding of the FCG model which is used increasingly to discriminate effects of sex chromosome complement and gonadal effects on sexually dimorphic non-gonadal phenotypes (Table 1).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Ryohei Sekido for the gift of the Sry construct and Dr. Louise D. McCullough for the gift of tissue for metaphase spreads. This work was supported by NIH grants NS043196, DK083561, and HD076125 and a Yamada Science Foundation grant to Y. Itoh, and an NSF award to RO. All animal use protocols were approved in advance by the UCLA Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee, the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Abbreviations

- FCG

Four core genotypes

- AGD

Anogenital distance

- FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization, WT: Wild type

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YI and APA designed the study and wrote the paper. YI designed and screened the DNA sequences of Sry transgene integration site, sequenced, and confirmed it by PCR. KK and SD contributed to screening. RM measured the anogenital distance in FCG mice. RO and JB confirmed the Sry transgene chromosomal location via FISH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yuichiro Itoh, Email: yitoh@ucla.edu.

Ryan Mackie, Email: mackie90125@gmail.com.

Kathy Kampf, Email: kkampf@mednet.ucla.edu.

Shelly Domadia, Email: shellydomadia@gmail.com.

Judith D Brown, Email: judy.brown@uconn.edu.

Rachel O’Neill, Email: rachel.oneill@uconn.edu.

Arthur P Arnold, Email: arnold@ucla.edu.

References

- 1.De Vries GJ, Rissman EF, Simerly RB, Yang LY, Scordalakes EM, Auger CJ, et al. A model system for study of sex chromosome effects on sexually dimorphic neural and behavioral traits. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9005–9014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-09005.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold AP, Burgoyne PS. Are XX and XY brain cells intrinsically different? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold AP. Sex chromosomes and brain gender. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:701–708. doi: 10.1038/nrn1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold AP. The organizational-activational hypothesis as the foundation for a unified theory of sexual differentiation of all mammalian tissues. Horm Behav. 2009;55:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold AP. Mouse models for evaluating sex chromosome effects that cause sex differences in non-gonadal tissues. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:377–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01831.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnold AP, Chen X. What does the "four core genotypes" mouse model tell us about sex differences in the brain and other tissues? Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy MM, Arnold AP. Reframing sexual differentiation of the brain. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:677–683. doi: 10.1038/nn.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnold AP, Chen X, Link JC, Itoh Y, Reue K. Cell-autonomous sex determination outside of the gonad. Dev Dyn. 2013;242:371–379. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Link JC, Chen X, Arnold AP, Reue K. Metabolic impact of sex chromosomes. Adipocyte. 2013;2:74–79. doi: 10.4161/adip.23320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox KH, Bonthuis PJ, Rissman EF. Mouse model systems to study sex chromosome genes and behavior: Relevance to humans. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35:405–419. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovell-Badge R, Robertson E. XY female mice resulting from a heritable mutation in the primary testis-determining gene. Tdy. Dev. 1990;109:635–646. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.3.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahadevaiah SK, Odorisio T, Elliott DJ, Rattigan A, Szot M, Laval SH, et al. Mouse homologues of the human AZF candidate gene RBM are expressed in spermatogonia and spermatids, and map to a Y chromosome deletion interval associated with a high incidence of sperm abnormalities. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:715–727. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abel JM, Witt DM, Rissman EF. Sex differences in the cerebellum and frontal cortex: roles of estrogen receptor alpha and sex chromosome genes. Neuroendocrinol. 2011;93:230–240. doi: 10.1159/000324402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markham JA, Jurgens HA, Auger CJ, De Vries GJ, Arnold AP, Juraska JM. Sex differences in mouse cortical thickness are independent of the complement of sex chromosomes. Neurosci. 2003;116:71–75. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker JM, Torregrossa MM, Arnold AP, Taylor JR. Dissociation of genetic and hormonal influences on sex differences in alcoholism-related behaviors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9140–9144. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0548-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazeyrat S, Saut N, Grigoriev V, Mahadevaiah SK, Ojarikre OA, Rattigan A, et al. A Y-encoded subunit of the translation initiation factor Eif2 is essential for mouse spermatogenesis. Nat Genet. 2001;29:49–53. doi: 10.1038/ng717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonthuis PJ, Cox KH, Rissman EF. X-chromosome dosage affects male sexual behavior. Horm Behav. 2012;64:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McPhie-Lalmansingh AA, Tejada LD, Weaver JL, Rissman EF. Sex chromosome complement affects social interactions in mice. Horm Behav. 2008;54:565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgoyne PS, Ojarikre OA, Turner JM. Evidence that postnatal growth retardation in XO mice is due to haploinsufficiency for a non-PAR X gene. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;99:252–256. doi: 10.1159/000071601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore S, Patel R, Hannsun G, Yang J, Tiwari-Woodruff SK. Sex chromosome complement influences functional callosal myelination. Neurosci. 2013;245:166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caeiro XE, Mir FR, Vivas LM, Carrer HF, Cambiasso MJ. Sex chromosome complement contributes to sex differences in bradycardic baroreflex response. Hypertension. 2011;58:505–511. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.175661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngun TC, Ghahramani NM, Creek MM, Williams-Burris SM, Barseghyan H, Itoh Y, et al. Feminized behavior and brain gene expression in a novel mouse model of Klinefelter Syndrome. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43:1043–1057. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0316-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carruth LL, Reisert I, Arnold AP. Sex chromosome genes directly affect brain sexual differentiation. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:933–934. doi: 10.1038/nn922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palaszynski KM, Smith DL, Kamrava S, Burgoyne PS, Arnold AP, Voskuhl RR. A Yin-Yang effect between sex chromosome complement and sex hormones on the immune response. Endocrinol. 2005;146:3280–3285. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen X, Watkins R, Delot E, Reliene R, Schiestl RH, Burgoyne PS, et al. Sex difference in neural tube defects in p53-null mice is caused by differences in the complement of X not Y genes. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:265–273. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Grisham W, Arnold AP. X chromosome number causes sex differences in gene expression in adult mouse striatum. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:768–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen X, McClusky R, Chen J, Beaven SW, Tontonoz P, Arnold AP, et al. The number of X chromosomes causes sex differences in adiposity in mice. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen X, McClusky R, Itoh Y, Reue K, Arnold AP. X and Y chromosome complement influence adiposity and metabolism in mice. Endocrinol. 2013;154:1092–1104. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X, Williams-Burris SM, McClusky R, Ngun TC, Ghahramani N, Barseghyan H, et al. The Sex Chromosome Trisomy mouse model of XXY and XYY: metabolism and motor performance. Biol Sex Differ. 2013;4:15. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park JH, Burns-Cusato M, Dominguez-Salazar E, Riggan A, Shetty S, Arnold AP, et al. Effects of sex chromosome aneuploidy on male sexual behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:609–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cocquet J, Ellis PJ, Yamauchi Y, Mahadevaiah SK, Affara NA, Ward MA, et al. The multicopy gene Sly represses the sex chromosomes in the male mouse germline after meiosis. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn JJ, Hitchcott PK, Umeda EA, Arnold AP, Taylor JR. Sex chromosome complement regulates habit formation. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1398–1400. doi: 10.1038/nn1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corre C, Friedel M, Vousden DA, Metcalf A, Spring S, Qiu LR, et al. Separate effects of sex hormones and sex chromosomes on brain structure and function revealed by high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging and spatial navigation assessment of the Four Core Genotype mouse model. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;epub Dec 2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Reynard LN, Cocquet J, Burgoyne PS. The multi-copy mouse gene Sycp3-like Y-linked (Sly) encodes an abundant spermatid protein that interacts with a histone acetyltransferase and an acrosomal protein. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:250–257. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox KH, Rissman EF. Sex differences in juvenile mouse social behavior are influenced by sex chromosomes and social context. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:465–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson DP, Huber SA, Moussawi M, Roberts B, Teuscher C, Watkins R, et al. Sex chromosome complement contributes to sex differences in Coxsackievirus B3 but not Influenza A virus pathogenesis. Biol Sex Differ. 2011;2:8. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dadam FM, Caeiro XE, Cisternas CD, Macchione AF, Cambiasso MJ, Vivas L. Effect of sex chromosome complement on sodium appetite and Fos-immunoreactivity induced by sodium depletion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;306:R175–R184. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00447.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasidhar MV, Itoh N, Gold SM, Lawson GW, Voskuhl RR. The XX sex chromosome complement in mice is associated with increased spontaneous lupus compared with XY. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1418–1422. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scerbo MJ, Freire-Regatillo A, Cisternas CD, Brunotto M, Arevalo MA, Garcia-Segura LM, et al. Neurogenin 3 mediates sex chromosome effects on the generation of sex differences in hypothalamic neuronal development. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:188. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durcova-Hills G, Burgoyne P, McLaren A. Analysis of sex differences in EGC imprinting. Dev Biol. 2004;268:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seney ML, Ekong KI, Ding Y, Tseng GC, Sibille E. Sex chromosome complement regulates expression of mood-related genes. Biol Sex Differ. 2013;4:20. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seney ML, Chang LC, Oh H, Wang X, Tseng GC, Lewis DA, et al. The role of genetic sex in affect regulation and expression of GABA-related enes across species. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:104. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ehlen JC, Hesse S, Pinckney L, Paul KN. Sex chromosomes regulate nighttime sleep propensity during recovery from sleep loss in mice. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seu E, Groman SM, Arnold AP, Jentsch JD. Sex chromosome complement influences operant responding for a palatable food in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2014;13:527–534. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ellis PJ, Clemente EJ, Ball P, Toure A, Ferguson L, Turner JM, et al. Deletions on mouse Yq lead to upregulation of multiple X- and Y-linked transcripts in spermatids. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2705–2715. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith-Bouvier DL, Divekar AA, Sasidhar M, Du S, Tiwari-Woodruff SK, King JK, et al. A role for sex chromosome complement in the female bias in autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1099–1108. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gatewood JD, Wills A, Shetty S, Xu J, Arnold AP, Burgoyne PS, et al. Sex chromosome complement and gonadal sex influence aggressive and parental behaviors in mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2335–2342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3743-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szot M, Grigoriev V, Mahadevaiah SK, Ojarikre OA, Toure A. von GE et al. Does Rbmy have a role in sperm development in mice? Cytogenet Genome Res. 2003;103:330–336. doi: 10.1159/000076821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gioiosa L, Chen X, Watkins R, Klanfer N, Bryant CD, Evans CJ, et al. Sex chromosome complement affects nociception in tests of acute and chronic exposure to morphine in mice. Horm Behav. 2008;53:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gioiosa L, Chen X, Watkins R, Umeda EA, Arnold AP. Sex chromosome complement affects nociception and analgesia in newborn mice. J Pain. 2008;9:962–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toure A, Szot M, Mahadevaiah SK, Rattigan A, Ojarikre OA, Burgoyne PS. A new deletion of the mouse Y chromosome long arm associated with the loss of Ssty expression, abnormal sperm development and sterility. Genetics. 2004;166:901–912. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.2.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toure A, Clemente EJ, Ellis P, Mahadevaiah SK, Ojarikre OA, Ball PA, et al. Identification of novel Y chromosome encoded transcripts by testis transcriptome analysis of mice with deletions of the Y chromosome long arm. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R102. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-12-r102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishikawa H, Rattigan A, Fundele R, Burgoyne PS. Effects of sex chromosome dosage on placental size in mice. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:483–488. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.012641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Nas A, GuhaThakurta D, Wang SS, Yehya N, Horvath S, Zhang B, et al. Elucidating the role of gonadal hormones in sexually dimorphic gene coexpression networks. Endocrinol. 2009;150:1235–1249. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ji H, Zheng W, Wu X, Liu J, Ecelbarger CM, Watkins R, et al. Sex chromosome effects unmasked in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:1275–1282. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.144949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vernet N, Mahadevaiah SK, Ojarikre OA, Longepied G, Prosser HM, Bradley A, et al. The Y-encoded gene zfy2 acts to remove cells with unpaired chromosomes at the first meiotic metaphase in male mice. Curr Biol. 2011;21:787–793. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vernet N, Mahadevaiah SK, Ellis PJ, de Rooij DG, Burgoyne PS. Spermatid development in XO male mice with varying Y chromosome short-arm gene content: evidence for a Y gene controlling the initiation of sperm morphogenesis. Reproduction. 2012;144:433–445. doi: 10.1530/REP-12-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kopsida E, Lynn PM, Humby T, Wilkinson LS, Davies W. Dissociable effects of Sry and sex chromosome complement on activity, feeding and anxiety-related behaviours in mice. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wagner CK, Xu J, Pfau JL, Quadros PS, De Vries GJ, Arnold AP. Neonatal mice possessing an Sry transgene show a masculinized pattern of progesterone receptor expression in the brain independent of sex chromosome status. Endocrinol. 2004;145:1046–1049. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuljis DA, Loh DH, Truong D, Vosko AM, Ong ML, McClusky R, et al. Gonadal- and sex-chromosome-dependent sex differences in the circadian system. Endocrinol. 2013;154:1501–1512. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ward MA, Burgoyne PS. The effects of deletions of the mouse Y chromosome long arm on sperm function–intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)-based analysis. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:652–658. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.048090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuo J, Hamid N, Bondar G, Dewing P, Clarkson J, Micevych P. Sex differences in hypothalamic astrocyte response to estradiol stimulation. Biol Sex Differ. 2010;1:7. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wijchers PJ, Yandim C, Panousopoulou E, Ahmad M, Harker N, Saveliev A, et al. Sexual dimorphism in mammalian autosomal gene regulation is determined not only by Sry but by sex chromosome complement as well. Dev Cell. 2010;19:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li J, Chen X, McClusky R, Ruiz-Sundstrom M, Itoh Y, Umar S, et al. The number of X chromosomes influences protection from cardiac ischaemia/reperfusion injury in mice: one X is better than two. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;102:375–394. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu J, Arnold AP. Sexually dimorphic expression of co-repressor Sin3A in mouse kidneys. Endocr Res. 2005;31:111–119. doi: 10.1080/07435800500229243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu J, Ji H, Zheng W, Wu X, Zhu JJ, Arnold AP, et al. Sex differences in renal angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) activity are 17beta-oestradiol-dependent and sex chromosome-independent. Biol Sex Differ. 2010;1:6. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu J, Deng X, Watkins R, Disteche CM. Sex-specific differences in expression of histone demethylases Utx and Uty in mouse brain and neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4521–4527. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5382-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu J, Deng X, Disteche CM. Sex-specific expression of the X-linked histone demethylase gene Jarid1c in brain. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu J, Burgoyne PS, Arnold AP. Sex differences in sex chromosome gene expression in mouse brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1409–1419. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.12.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu J, Taya S, Kaibuchi K, Arnold AP. Sexually dimorphic expression of Usp9x is related to sex chromosome complement in adult mouse brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:3017–3022. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu J, Taya S, Kaibuchi K, Arnold AP. Spatially and temporally specific expression in mouse hippocampus of Usp9x, a ubiquitin-specific protease involved in synaptic development. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80:47–55. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu J, Watkins R, Arnold AP. Sexually dimorphic expression of the X-linked gene Eif2s3x mRNA but not protein in mouse brain. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamauchi Y, Riel JM, Stoytcheva Z, Burgoyne PS, Ward MA. Deficiency in mouse Y chromosome long arm gene complement is associated with sperm DNA damage. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R66. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-6-r66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Manwani B, Bentivegna K, Benashski SE, Venna VR, Xu Y, Arnold AP, et al. Sex differences in ischemic stroke sensitivity are influenced by gonadal hormones, not by sex chromosome complement. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:221–229. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schneider JE, Wysocki CJ, Nygy J, Whitney G. Determining the sex of neonatal mice (Mus musculus) Behav Res Methods Instrum. 1978;10:105. doi: 10.3758/BF03205110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hotchkiss AK, Vandenbergh JG. The anogenital distance index of mice (Mus musculus domesticus): an analysis. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2005;44:46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ninomiya T, Iwabuchi T, Soga Y, Yuki A. Direct sequencing of flanking regions of a transgene amplified by inverted PCR. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:1869–1872. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.54.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Arnold C, Hodgson IJ. Vectorette PCR: a novel approach to genomic walking. PCR Methods Appl. 1991;1:39–42. doi: 10.1101/gr.1.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:279–284. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Du S, Itoh N, Askarinam S, Hill H, Arnold AP, Voskuhl RR. XY sex chromosome complement, compared with XX, in the CNS confers greater neurodegeneration during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2806–2811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307091111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]