Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a crucial role in tumor angiogenesis. VEGF induces new vessel formation and tumor growth by inducing mitogenesis and chemotaxis of normal endothelial cells and increasing vascular permeability. However, little is known about VEGF function in the proliferation, survival or migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HCC). In the present study, we have found that VEGF receptors are expressed in HCC line BEL7402 and human hepatocellular carcinoma specimens. Importantly, VEGF receptor expression correlates with the development of the carcinoma. By using a comprehensive approaches including TUNEL assay, transwell and wound healing assays, migration and invasion assays, adhesion assay, western blot and quantitative RT-PCR, we have shown that knockdown of VEGF165 expression by shRNA inhibits the proliferation, migration, survival and adhesion ability of BEL7402. Knockdown of VEGF165 decreased the expression of NF-κB p65 and PKCα while increased the expression of p53 signaling molecules, suggesting that VEGF functions in HCC proliferation and migration are mediated by P65, PKCα and/or p53.

Keywords: RNA interference, vascular endothelial growth factor, hepatocellular carcinoma, migration, proliferation

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignant cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Several factors contribute to the development of HCC including aberrant viral protein expression, genomic instability with/without insertions of viral DNAs, gene mutations, epigenetic gene modification, oxidative stress, and alteration of the microenvironment such as inflammation, fibrosis, and emergence of stem/progenitor cells as a result of repeated necrosis and regeneration of hepatocytes [1]. Current treatments for HCC include surgical approaches such as resection and transplantation, local tumor ablation, and chemoembolization etc. However, none of them is effective for all patients [2]. Angiogenesis is related to the growth and metastasis of human tumors [3]. Although numerous growth factors are involved, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been shown to play a crucial role in tumor angiogenesis [4]. Binding of VEGF to its receptors contributes to new vessel formation and tumor growth by inducing mitogenesis and chemotaxis of normal endothelial cells and increasing vascular permeability [5]. Interestingly, in leukemia, VEGF is involved in cell proliferation, survival and migration [6,7]. Little is known, however, if VEGF regulates human HCC proliferation, survival or migration.

In this study, we explored the effect of VEGF on the proliferation and migration of HCC cell BEL7402 cells. We found that VEGF165 plays an important role in the proliferation, migration and adhesion ability of BEL7402 cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Construction of VEGF short hairpin RNA (shRNA) adenoviral vector

VEGF165 shRNA (shVEGF) were designed using a dedicated program provided by OriGene. Oligonucleotides corresponding to the nucleotides of 532–560 in human VEGF165 mRNA (GenBank accession no: GI: 197692602) were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai). The shRNA sequences were 5′-CGC GTC GAG TTA AAC GAA CGT ACT TGC AGA TGT GAT TCA AGA GAT CAC ATC TGC AAG TACG TTC GTT TAA CTC TTT TTT GGA AA-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGC TTT TCC AAA AAA GAG TTA AAC GAA CGT ACT TGC AGA TGT GAT CTC TTG AAT CAC ATC TGC AAG TAC GTT CGT TTA ACT CGA-3′ (antisense). The Double-stranded DNA fragment was cloned into the MluI/HindIII restriction site of the pRNAT-H1.1/Adeno vector (GenScript Corporation., America), resulting in pRNAT-H1.1-shVEGF165. The inserted sequences were verified by restricted enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing. Adenovirus expressing shVEGF was packaged in BJ5183-AD-1 (Agilent) and propagated in AD-293 cells (Invitrogen) by following the manufacture’s instruction. The adenovirus was purified by cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation [8].

2.2 Transfections and adenovirus infections

The transduction of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells with adenovirus was carried out according to the method described previously [9]. Briefly, BEL 7402 cells were maintained in RPM1640 with 10% FBS, and infected with Ad-GFP and Ad-shVEGF165 viruses at 100 multiplicity of infection (MOI).

2.3 Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA from cultured BEL-7402 cells was extracted using TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen). The RNA concentration was determined by UV spectrophotometry. qRT-PCR was performed using THUNDERBIRD SYBR Master Mix (TOYOBO, Japan). The primer sequences were: hVEGF165: 5′-ACA GAC ACC GCT CCT AGC CC-3′ (forward), 5′-CGA GAA CAG CCC AGA AGT TGG-3′ (reverse); β-actin: 5′-GTC CAC CGC AAA TGC TTC TA-3′ (forward), 5′-TGC TGT CAC CTT CAC CGT TC-3′ (reverse). qPCR was performed on a Real-time PCR Detection System (Slan, Hongshi) with the following cycles: 95 °C for 1 min, followed by 95 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 45 s for 40 cycles. β-actin expression was used as an internal control.

2.4 Western blot

30 μg of proteins were separated in a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore). The membrane was rinsed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) and blocked with 5% fat free milk in TBS at room temperature for 1 h. After being blocked, the membrane was incubated with anti-VEGF (Santa Cruz) or anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma) (1:500 and 1:5000 dilution, respectively) followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10000 dilution; Santa Cruz). The immunoblots were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence reaction (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and measured with densitometry.

2.5 Quantification of VEGF protein secretion

BEL7402 cell culture supernatants were centrifuged for 5 min to remove cells and cell debris. VEGF protein that accumulated in the culture medium and dilutions of a recombinant human VEGF165 protein standard were analyzed using Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D System)[10]. VEGF165 concentrations were measured at the absorbance 450 nm with a Universal Microplate Spectrophotometer (Bio-TEK Instrument).

2.6 Immunostaining and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

VEGF receptor expression in BEL7402 cells was detected by immunostaining. The cells were incubated with primary antibody against VEGF receptors followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:50, Zhongshan Goldenbridge Biotechnology). The stained cells were analyzed with flow cytometry. For IHC staining, human liver cancer specimen sections were rehydrated, blocked with 5% goat serum and permeabilized with 0.01% Triton X-100 in PBS, and incubated with VEGF receptor antibodies overnight at 4 °C followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The receptor expressions were visualized by DAB staining, and the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

2.7 Cell apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis was detected using a TUNEL assay kit (Beyotime) by following the manufacturer’s instruction. Cells were fixed with 4% Paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. After washed with PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS was added for 2 min. The cells were then incubated with 50 μl TUNEL test solution in dark at 37°C for 60 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS. The ratio of cell apoptosis was observed flow cytometry analysis [11].

2.8 Cell migration assay

Cell migration was detected by transwell migration assay as well as wound healing assay. For the transwell assay, BEL7402 cells were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-shVEGF, or treated with VEGFR1-I or VEGFR2-I for 48 hours. The cells were then trypsinized and suspended in 2% FBS contained medium. 200 μl of the cell suspensions containing 2×105 cells were seeded into the upper chamber of a 24-well transwell (pore size, 8 μm, Millipore). Transwells were then inserted into a 24-well plate containing 600μl RPM1640 medium supplemented with10% FBS and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere for 12 h to allow BEL7402 cells to migrate. Cells on the upper side of the filter (not migrated) were removed with cotton swabs. Migrated cells on the lower side of the filter were fixed and stained with DAPI. The number of BEL7402 cells that had migrated to the lower surface of the membrane was counted in 5 random and non-repeated high-power fields under a fluorescence microscope. The average migration cell numbers of each group were calculated. Each assay was performed in triplicate wells. The scrape migration assays were performed using the CytoSelect™ 24-well Wound Healing Assay Kit by following the manufacturer’s protocol. The inserts create a wound field with a defined gap of 0.9 mm for measuring the migratory rates of cells. BEL7402 cells were treated similarly as described in the transwell assay. The cell migration was observed by phase-contrast microscopy. The migration distance was calculated by measuring the distance from the wound edge to several border zones of the maximally migrated cells. The percentage of closure was calculated as migratory distance from both sides versus the distances to the middle of the wound. Each assay was performed in triplicate wells.

2.9 Invasion assay

To test the invasive capability of BEL7402 cells, a barrier of extracellular matrix was established using Matrigel in the transwells. 40 μl of diluted Matrigel (0.125 μg/μl) was added to the upper chamber of each Transwell and incubated in room temparature overnight until the Matrigel has completely dried onto the porous membranes. Matrigel was then reconstituted by adding 40 μl of DMEM to the upper chamber and incubate at 37°C for 1 h prior to the invasion assay. 100 μl of cells infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-shVEGF, or treated with VEGFR1-I or VEGFR2-I (1x106 cells/ml in DMEM containing 2% FBS) were added to the upper chamber of the matrigel-coated Transwells. 600 μl of DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to the bottom well of each Transwell chamber. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 5 h. To determine the invasion, cells in the upper portion of the Transwell filters were removed using cotton swabs. Migrated cells were fixed using methanol at room temperature for 15 min, and stained with propidium iodide for 15 min followed by washing the transwell inserts with H2O to remove the excess stain. The inserts were dried in the air, and photographed under a microscope [12].

2.10 Adhesion assay

BEL7402 cells were transduced with 100 MOI of Ad-GFP or Ad-shVEGF165 for 3 days. Cells were trypsinized, suspended in PBS, counted, and then seeded onto 24-well plates (2×105 cells/well). For static adhesion, cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C for 2 h without shaking. For shaken Adhesion assay, the plates were placed on a horizontal reciprocal shaker (Nippon Genetics, Tokyo, Japan) and shaken at 110 strokes/min for 2 h [13]. Cells were gently washed with PBS for three times to remove the non-adherent cells. The remaining adherent cells were observed using a bright field microscope (Olympus, Shibuya, Japan) and quantified using Image Pro6.0 software. Cells were then treated with 300 μl MTT reagent at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 4h. The absorbance at 490 nm of the colored solution was measured by a spectrophotometer [14]. Each assay was performed in triplicate wells.

2.11 Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± SD. The data were analyzed by Student’s t test to determine statistical significance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 VEGF receptors are expressed in BEL7402 HCC cells and human pathology specimens

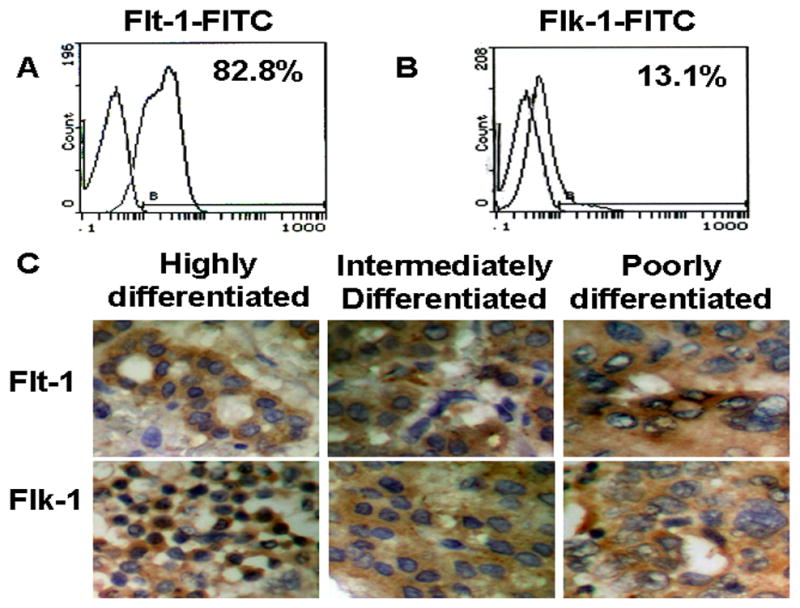

VEGF has been shown to express in HCC [15]. It is unknown, however, if VEGF receptors are also expressed in HCC. In order to test if VEGF plays a role in HCC cellular function, we first detected if HCC express VEGF receptors. In BEL7402 cells, VEGF receptor expression was detected by Flow Cytometry. We found that 82.8% of the cultured BEL7402 cells expressed VEGFR1 (Flt-1) (Fig. 1A), while only 13.1% of the cells expressed VEGFR2 (Flk-1) (Fig. 1B). To test if VEGF receptors are expressed in liver cancer cells in vivo, we performed IHC staining to detect VEGF, Flt-1 and Flk-1 expression in human liver cancer specimens at three different differentiation stages. We found that VEGF, Flk-1 and Flt-1 were all expressed in liver cancer cells (Fig. 1C). Importantly, it appeared that the receptor expression correlated with the cancer development. More Flk-1 and Flt-1 expression were detected in the poorly differentiated cancer cells as compared to the well differentiated cells. These results suggest that VEGF may play a role in the progression or metastasis of liver cancer in vivo.

Fig. 1. Expression of VEGF receptors in BEL7402 cells and human liver cancer specimens.

A–B, The expression of VEGF receptors in BEL7402 cells were detected by Flow Cytometry. C, Expression of VEGF receptors in well-, moderately- and poorly-differentiated human liver cancer specimens was detected by IHC. Brown staining represents the positive expression. Blue-violet stains nuclei.

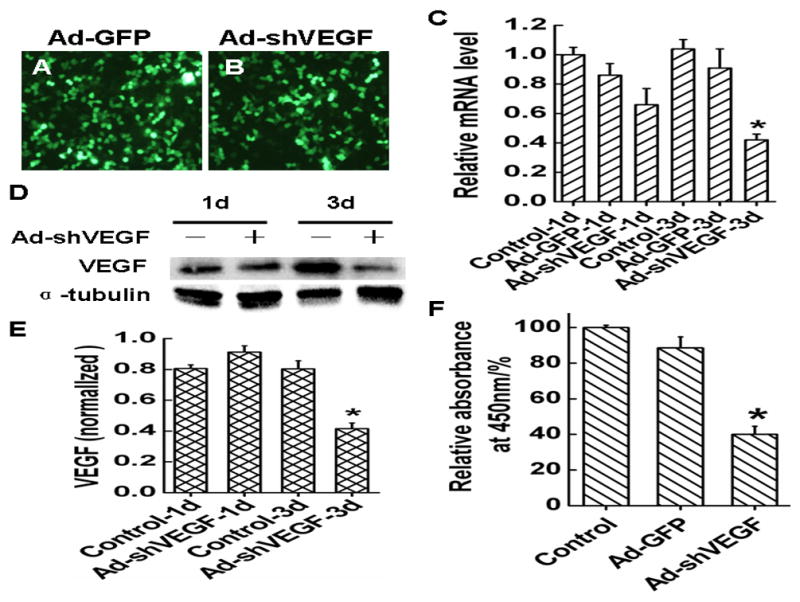

In order to test if VEGF indeed plays a role in adhesion, migration or survival of HCC, we constructed an adenovirus expressing VEGF165 shRNA (Ad-shVEGF165). This adenoviral vector transduction resulted in a 100% of infection efficiency in BEL7402 cells (Fig. 2B), similar to the control adenovirus (Fig. 2A). The shRNA expressed by Ad-shVEGF165 effectively blocked VEGF mRNA (Fig. 2C) and protein expression (Fig. 2D and 2E) after 3 days of the transduction. shRNA knockdown also caused the reduction of VEGF secretion to the supernatant of BEL7402 cell cultures (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2. VEGF shRNA effectively knocks down VEGF expression in BEL7402 cells.

A–B, Adenoviral vector expressing VEGF shRNA (Ad-shVEGF165) infection transduced all the BEL7402 cells, similar to the control Ad-GFP adenovirus. C, Ad-shVEGF165 effectively blocked VEGF mRNA expression after 3 days of transduction. D–E, Ad-shVEGF165 effectively blocked VEGF protein expression after 3 days of transduction. F, Ad-shVEGF165 reduced the VEGF secreted into the supernatant of BEL7402 cell culture.

3.2 VEGF regulates HCC migration

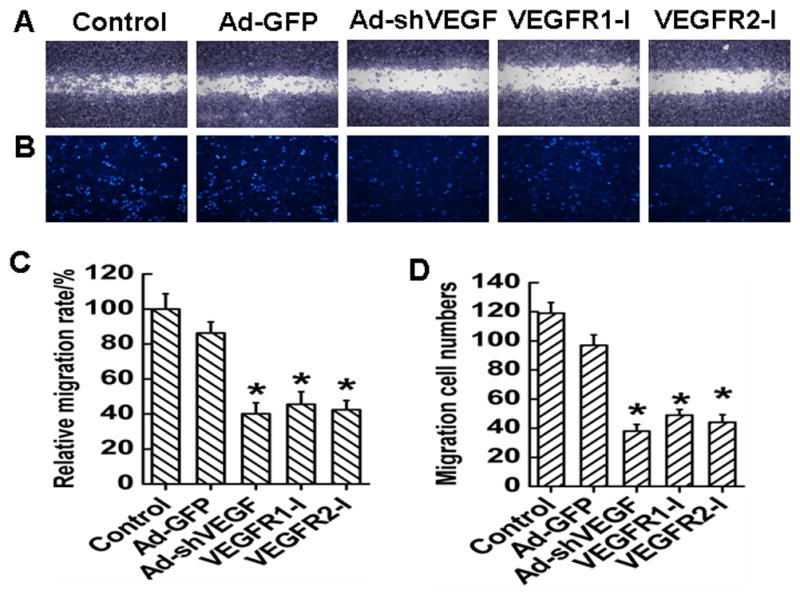

Cell migration is an important process in tumor progression and metastasis. To test whether VEGF plays a role in the migration of HCC, we performed transwell and wound healing assay using BEL7402 cells. Serum was used to induce the migration. Both wound healing (Fig. 3A and .3C) and transwell assays (Fig. 3B and 3D) showed that compared with the control and Ad-GFP groups, the migration of BEL7402 cells was significantly inhibited when VEGF was silenced or VEGF receptors were blocked. These data suggest that VEGF plays a critical role in HCC migration.

Fig. 3. Effect of VEGF on migration of HCC BEL7402 cells.

A, Representative migration images of BEL7402 cells in wound healing assay for 24 h. Cells were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-shVEGF165, or treated with VEGF receptor inhibitors as indicated before the assay. B, Representative migration images of BEL7402 cells in transwell migration system 24 h after serum induction. C, Quantification of the effect of VEGF on BEL7402 cells migration observed in A. Ad-shVEGF165, VEGFR1-I, VEGFR2-I treatment inhibited the migration. D, Quantification of the cells migrated through the transwell observed in B. Ad-shVEGF165, VEGFR1-I, VEGFR2-I treatment reduced the number of BEL7402 cells migrated through the transwell. *P< 0.05 vs control and Ad-GFP groups.

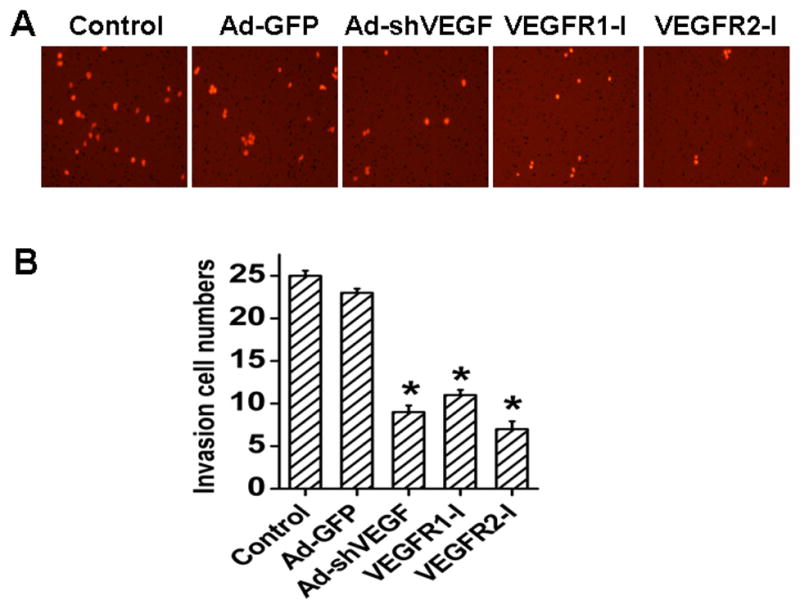

3.3 VEGF is important for the invasive ability of HCC

In order to test if VEGF is important to the invading capability of HCC, invasion assay was performed. BEL7402 cells were tested for their ability to invade through matrigel-coated porous membranes in transwell inserts. Serum was used as a chemoattractant in this assay. As shown in Fig. 4A–4B, VEGF knockdown or VEGF receptor blockade significantly reduced the numbers of the cells that invaded through the matrigel. It appeared that VEGFR2 was more important than VEGFR1 in mediating BEL7402 cell migration because VEGFR2 inhibitor had a greater effect than VEGFR1 inhibitor in blocking the cell migration.

Fig. 4. Effect of VEGF on invasion of BEL7402.

A, Representative images of BEL7402 cells invading the matrigel. Cells were treated with or without Ad-GFP, Ad-shVEGF165, VEGFR1-I, or VEGFR2-I as indicated before the invasion assay. Cells invaded through the matrigel and migrated onto the lower surface of the porous membrane were stained in red. shVEGF165, VEGFR1-I, or VEGFR2-I treatment resulted in a significant inhibition of the invasive ability of BEL7402 cells. B, Quantification of the numbers of cells that invaded through the matrigel observed in panel A. *P< 0.05 vs control and Ad-GFP groups, n=15.

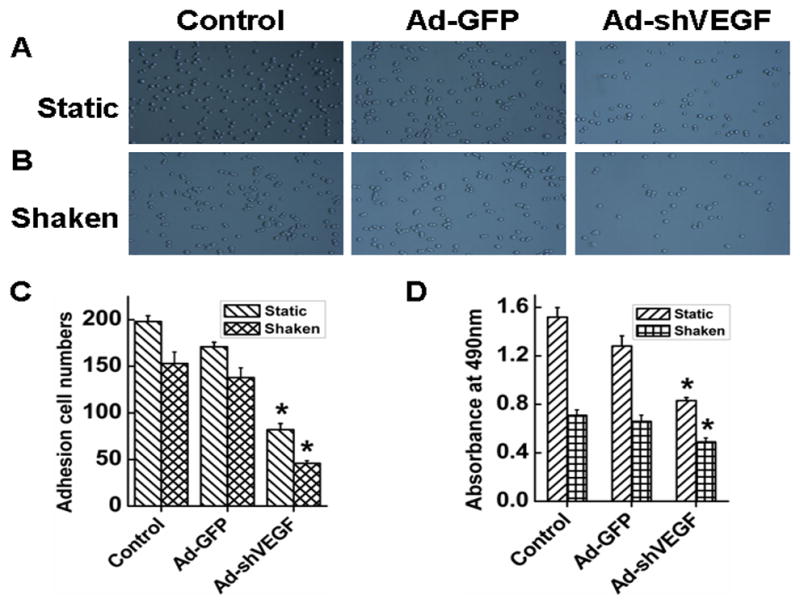

3.4 VEGF promotes HCC adhesion in both static and shaken conditions

Adhesion is an important step in tumor metastasis. HCC may metastasize to other organs through blood flow. Therefore, we sought to determine if VEGF affects HCC adhesion in both static and shaken conditions. As shown in Fig. 5A–5D, compared with the control and Ad-GFP groups, knockdown of VEGF165 significantly reduced the cell adhesion. It appeared that VEGF165 had a greater effect on the adhesion of BEL7402 cells in static condition than shaken condition because knockdown of VEGF165 inhibited most of the adhesion in static condition (Ad-GFP) while inhibiting 50% of the adhesion in shaken conditions. Nevertheless, these data suggest that VEGF is potentially important in promoting HCC metastasis by inducing HCC adhesion to blood vessel, leading to vascular invasion in addition to intrahepatic metastasis. Knockdown of VEGF also reduced the cell proliferation, but the reduction in proliferation is much less than the reduction of the adhesion, demonstrating the role of VEGF in HCC adhesion.

Fig. 5. Effect of VEGF on adhesion of BEL7402 cells.

A–B, Representative images of BEL7402 cell adhesion in static (A) and shaken adhesion conditions (B). Cells were treated or without (Ctrl) Ad-GFP or Ad-shVEGF165 for 3 days before seeding onto the 24-well plates for adhesion assay. C, Quantification of the cells adhering to the substrate in static and shaken conditions as observed in panel A and B. Cells were counted using Image Pro6.01 software. *P<0.05 vs control and Ad-GFP groups in corresponding conditions, n=15. D, Cell proliferation during the adhesion assay was measured by MTT. The absorbance of the cells adhered to the substrate under shaken and static culture conditions was evaluated at 490nm. *P<0.05 vs control and Ad-GFP groups, n=15.

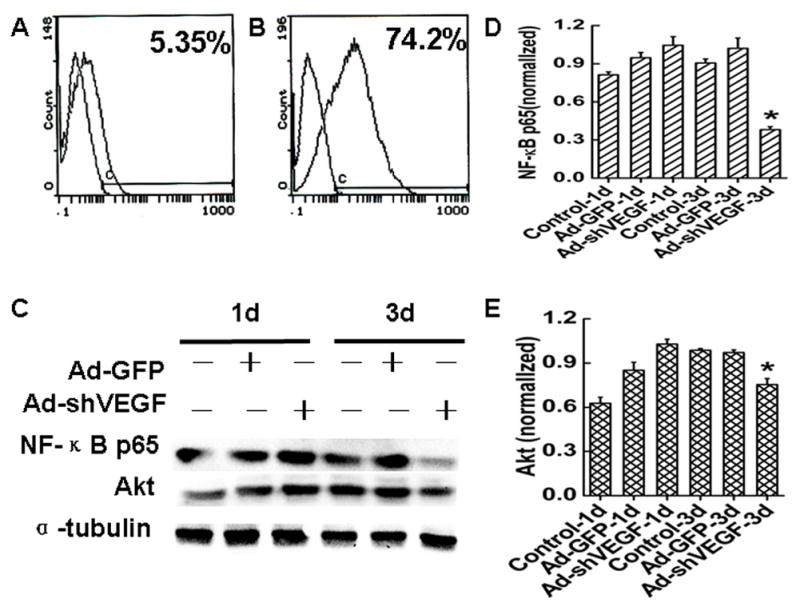

3.5 VEGF plays a role in HCC survival

Cancer cell survival contributes to the tumor growth. To determine if VEGF plays a role in HCC survival, we tested the effect of VEGF on the apoptosis of BEL7402 cells. As shown in Fig 6A and 6B, shRNA knockdown of VEGF caused an apoptosis rate of 74.2% in BEL7402 cells, while control cells only showed a 5.35% of apoptosis. Previously studies have shown that VEGF promotes leukemia cell survival via the activation of nuclear factor kappa B p65 (NF-κB p65), mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK)/Erk and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathways [6,16]. We found that knockdown of VEGF165 in BEL7402 cells decreased the expression of NF-κB p65 and Akt (Fig. 6D and 6E), suggesting that VEGF regulates BEL7402 cell survival through distinct signaling pathways compared with leukemia cells.

Fig. 6. Effects of VEGF on the apoptosis of HCC.

A–B, Effects of VEGF siRNA on BEL7402 cells apoptosis was measured by the FCM assay. The peak of cell apoptosis in Ad-shVEGF165 (B) group was 13 times more than the Ad-GFP (A) groups. C, Western blot analysis of NF-κB p65 and Akt protein levels in BEL7402 cells treated with Ad-shVEGF165. D–E, Quantitative assay of NF-κB p65 (D) (*P< 0.05, vs. control and Ad-GFP groups.) and Akt (E) (*P< 0.05, vs. control and Ad-GFP groups.) proteins expression in BEL7402 cells by optical density value.

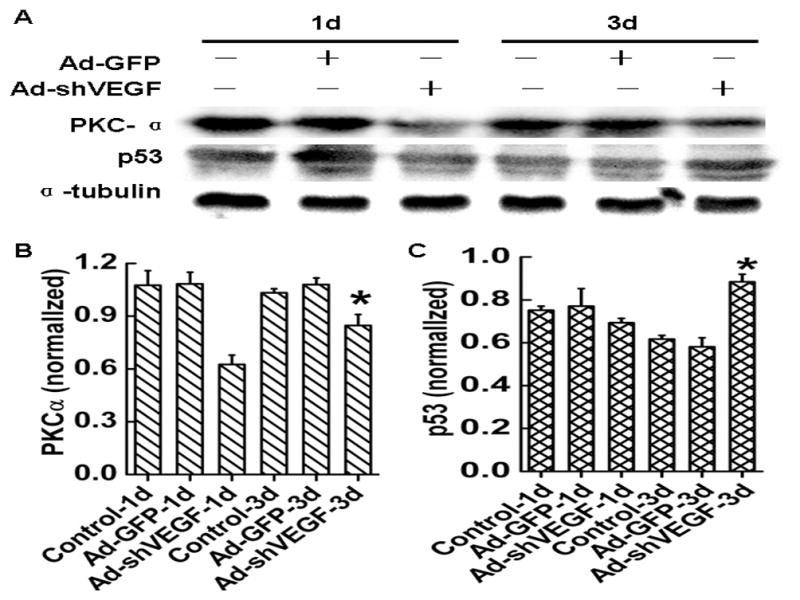

3.6 VEGF regulates expression of protein kinase C alpha (PKCα) and p53 genes

Tumor suppressor genes p53 plays a key role in restraining cancer initiation and progression through the induction of cell-cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence and apoptosis [17–19]. Protein kinase C alpha (PKCα) promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of several cancer cells including human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting the levels of p53 and p21(WAF1/CIP1)[20–23]. To explore the mechanism by which VEGF regulates the survival, migration and adhesion of HCC, we tested if VEGF is involved in the expression of p53 and PKCα. Western blot analysis showed that knockdown of VEGF165 significantly diminished PKCα expression while increased p53 expression compared to the control group (Fig. 7A–7C). These data suggest that VEGF may stimulate the migration, adhesion and survival of HCC through regulating PKCα/p53 signaling pathway.

Fig. 7. Effects of VEGF on PKCα and p53 expression in BEL7402 cells.

A, PKCα and p53 protein levels in BEL7402 cells were detected by western blot analysis. Cells were treated with Ad-GFP or Ad-shVEGF165 for 1 or 3 days as indicated before the blotting analysis. α-tubulin served as an internal control. B–C, Quantitative analysis of PKCα (B) and p53(C) protein expression in BEL7402 cells by optical density value. *P< 0.05 vs control and Ad-GFP groups, n=5.

Discussion

VEGF acts as an angiogenic factor in neo-angiogenesis by promoting the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells [24]. Judah Folkman proposed about 40 years ago that all tumors were angiogenesis-dependent. He assumed that cutting off blood supply would kill the tumor [25]. However, recent studies have showed that the tumor can generate their own vascular system independent of the host blood vessels [26]. VEGF appears to play a crucial role in either exogenous or endogenous neo-angiogenesis [27]. In addition to its angiogenic effect, previous studies have also shown that hematopoietic stem cells (HSC), leukemia, human pancreatic cancer cells and multiple myeloma express VEGF receptors, and are able to generate functional autocrine loops supporting their proliferation, migration, adhesion and survival[6,7,28,29–32]. Our in vitro finding further demonstrates that VEGF may regulate HCC survival or metastasis through a pathway independent of its angiogenesis effect.

Both HCC line BEL7402 cells and cells in human liver cancer specimens express VEGF receptors. Knockdown of VEGF attenuated the migration, invasion, adhesion and survival of BEL7402 cells, suggesting that VEGF may be important for both the development of HCC in liver tissue and metastasis to other organs. Since these assays were all done in vitro, the effects are independent of its angiogenic effect. Interestingly, Knockdown of VEGF inhibits HCC adhesion in both static and shaken conditions, indicating that VEGF may play a role in both vascular invasion and intrahepatic invasion of HCC.

Previously studies have shown that external VEGF promotes leukemia cells survival through the activation of nuclear factor kappa B p65 (NF-κB p65), internal VEGF regulates leukemia cells survival via the constitutive activation of MAPK/Erk and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathways [6,16]. We found that knockdown of VEGF165 in BEL7402 cells inhibits the expression of NF-κB p65 and Akt, suggesting that internal VEGF regulates HCC cell survival through signaling pathways distinct from that in leukemia cells. Studies from many other groups also show that VEGF regulates cell survival via different mechanisms in different cells. For example, Gerber [29] has reported that internal VEGF regulates HSC survival by the activation of Akt. Ulivi’ study [32] has shown that VEGFR blocker (Sorafenib) induces cells apoptosis through RAF/MEK/ERK and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathways in human pancreatic cancer cells. Recently, Ramakrishnan [31] demonstrates that Sorafenib inhibits myeloma cell proliferation through inactivation of STAT3 and MEK/ERK. These studies indicate that VEGF may regulate cell survival and proliferation via various signaling pathways depending on the cellular and environment context.

Tumor suppressor genes, particularly p53, play a key role in restraining cancer initiation and progression through the induction of cell-cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence and apoptosis [17–19]. We found that knockdown of VEGF significantly increased the expression of p53 in BEL7402 cells, concordant with its inhibitory effect in cell migration, invasion, adhesion and survival. Interestingly, PKCα inhibitor or PKCα knockdown decreases the proliferation, migration, and invasion of urinary bladder carcinoma cells and human hepatocellular carcinoma cells, associated with the increase in the levels of p53 and p21(WAF1/CIP1)[20–23]. Our data have shown that shRNA knockdown of VEGF inhibits the expression of PKCα and increases expression of p53. Therefore, VEGF is likely to promote HCC migration, invasion and adhesion through PKCα/p53 pathway.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from National natural Science Foundation of China (81170095; 30700306), Hubei Health Department Science Foundation (JX5B24), Hubei Education Department Science Foundation (T2008010, T201112, Q200524003), China; And National Institutes of Health (HL093429 and HL107526).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

All authors have read and approved the manuscript, and there is no ethical problem or conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Taro Y, Kaneko S. Molecular pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2010;37(1):14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Harry, Xia H. Novel therapeutic approaches for hepatocellulcar carcinoma:Fact and fiction. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(11):1641–2. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrara N. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. Semin Oncol. 2002;29 (6 Suppl 16):10–4. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernando NH, Hurwitz HI. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Semin Oncol. 2003;30(3 Suppl 6):39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(03)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yancopoulos GD, Davis S, Gale NW, Rudge JS, Wiegand SJ, Holash J. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature. 2000;407(6801):242–8. doi: 10.1038/35025215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos SC, Dias S. Internal and external autocrine VEGF/KDR loops regulate survival of subsets of acute leukemia through distinct signaling pathways. Blood. 2004;103(10):3883–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dias S, Hattori K, Heissig B, Zhu Z, Wu Y, Witte L, et al. Inhibition of both paracrine and autocrine VEGF/ VEGFR-2 signaling pathways is essential to induce long-term remission of xenotransplanted human leukemias. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(19):10857–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191117498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chartier C, Degryse E, Gantzer M, Dieterle A, Pavirani A, Mehtali M. Efficient generation of recombinant adenovirus vectors by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1996;70: 4805–10. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4805-4810.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang J, Wang J, Guo L, Kong X, Yang J, Zheng F, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Modified with Stromal Cell-Derived Factor 1α Improve Cardiac Remodeling via Paracrine Activation of Hepatocyte Growth Factor in a Rat Model of Myocardial Infarction. Mol Cells. 2010;29(1):9–19. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang J, Wang J, Kong X, Yang J, Guo L, Zheng F, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes cardiac stem cell migration via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315(20):3521–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Y, Lehrach H, Janitz M. Apoptosis screening of human chromosome 21 proteins reveals novel cell death regulators. Mol Biol Rep. 2010;37(7):3381–7. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9926-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw LM. Tumor cell invasion assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;294:97–105. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-860-9:097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagasaki A, Kanada M, Uyeda TQ. Cell adhesion molecules regulate contractile ring-independent cytokinesis in Dictyostelium discoideum. Cell Res. 2009;19(2):236–46. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Xue L, Yan H, Li J, Lu Y. Effects of ROCK inhibitor, Y-27632, on adhesion and mobility in esophageal squamous cell cancer cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2010;37(4):1971–7. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deli G, Jin CH, Mu R, Yang S, Liang Y, Chen D, et al. Immunohistochemical assessment of angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma and surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(7):960–3. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i7.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fragoso R, Elias AP, Dias S. Autocrine VEGF loops, signaling pathways, and acute leukemia regulation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48(3):481–8. doi: 10.1080/10428190601064720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danilova N, Sakamoto KM, Lin S. p53 family in development. Mech Dev. 2008;125(11–12):919–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molchadsky A, Rivlin N, Brosh R, Rotter V, Sarig R. p53 is balancing development, differentiation and de-differentiation to assure cancer prevention. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(9):1501–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guan Y-H, He Q, La Z. Roles of p53 in carcinogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Mol. 2006;2:191–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aaltonen V, Peltonen J. PKCalpha/beta I inhibitor Go6976 induces dephosphorylation of constitutively hyperphosphorylated Rb and G1 arrest in T24 cells. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(10):3995–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu TT, Hsieh YH, Hsieh YS, Liu JY. Reduction of PKC alpha decreases cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of human malignant hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103(1):9–20. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deeds L, Teodorescu S, Chu M, Yu Q, Chen CY. A p53-independent G1 cell cycle checkpoint induced by the suppression of protein kinase C alpha and theta isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):39782–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coutinho I, Pereira G, Leão M, Gonçalves J, Côrte-Real M, Saraiva L. Differential regulation of p53 function by protein kinase C isoforms revealed by a yeast cell system. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(22):3582–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frankel AE, Gill PS. VEGF and myeloid leukemias. Leuk Res. 2004;28:675. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis. Therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Rong, Chadalavada Kalyani, Wilshire Jennifer, Kowalik Urszula, Hovinga Koos E, Geber Adam, et al. Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour endothelium. Nature. 2010;468:829–33. doi: 10.1038/nature09624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geva R, Prenen H, Topal B, Aerts R, Vannoote J, Van Cutsem E. Biologic modulation of chemotherapy in patients with hepatic colorectal metastases: the role of anti-VEGF and anti-EGFR antibodies. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102(8):937–45. doi: 10.1002/jso.21760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dias S, Hattori K, Zhu Z, Heissig B, Choy M, Lane W, et al. Autocrine stimulation of VEGFR-2 activates human leukemic cell growth and migration. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(4):511–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI8978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerber HP, Malik AK, Solar GP, Sherman D, Liang XH, Meng G, et al. VEGF regulates haematopoietic stem cell survival by an internal autocrine loop mechanism. Nature. 2002;417:954–8. doi: 10.1038/nature00821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Podar K, Anderson KC. Inhibition of VEGF signaling pathways in multiple myeloma and other malignancies. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(5):538–42. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramakrishnan V, Timm M, Haug JL, Kimlinger TK, Wellik LE, Witzig TE, et al. Sorafenib, a dual Raf kinase/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor has significant anti-myeloma activity and synergizes with common anti-myeloma drugs. Oncogene. 2010;29(8):1190–202. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulivi P, Arienti C, Amadori D, Fabbri F, Carloni S, Tesei A, et al. Role of RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, p-STAT-3 and Mcl-1 in sorafenib activity in human pancreatic cancer cell lines. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220(1):214–21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]