Abstract

Combining agents with different mechanisms of action may be necessary for meaningful results in treating ALS. The combinations of minocycline-creatine and celecoxib-creatine have additive effects in the murine model. New trial designs are needed to efficiently screen the growing number of potential neuroprotective agents. Our objective was to assess two drug combinations in ALS using a novel phase II trial design. We conducted a randomized, double-blind selection trial in sequential pools of 60 patients. Participants received minocycline (100 mg)-creatine (10 g) twice daily or celecoxib (400 mg)-creatine (10 g) twice daily for six months. The primary objective was treatment selection based on which combination best slowed deterioration in the ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R); the trial could be stopped after one pool if the difference between the two arms was adequately large. At trial conclusion, each arm was compared to a historical control group in a futility analysis. Safety measures were also examined. After the first patient pool, the mean six-month decline in ALSFRS-R was 5.27 (SD=5.54) in the celecoxib-creatine group and 6.47 (SD=9.14) in the minocycline-creatine group. The corresponding decline was 5.82 (SD=6.77) in the historical controls. The difference between the two sample means exceeded the stopping criterion. The null hypothesis of superiority was not rejected in the futility analysis. Skin rash occurred more frequently in the celecoxib-creatine group. In conclusion, the celecoxib-creatine combination was selected as preferable to the minocycline-creatine combination for further evaluation. This phase II design was efficient, leading to treatment selection after just 60 patients, and can be used in other phase II trials to assess different agents.

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS, minocycline, celecoxib, creatine, clinical trial, neuroprotection, combination therapy, selection trial

Introduction

Although the mechanisms of cell death in ALS are not fully elucidated, free radical toxicity, glutamate excitotoxicity, and mitochondrial dysfunction seem to activate enzymes that promote inflammation and apoptosis (1–6). Since the advent of the murine model of ALS (7) all but one of the numerous treatment trials aimed at a specific mechanism of neurodegeneration have failed in humans (8). Until stronger agents are identified, combining therapies that target more than one mechanism of neurodegeneration might give a more meaningful benefit than single agents. Several potential neuroprotective medications have additive effects when administered in combination in the mouse model. Individually, minocycline, creatine and celecoxib prolong survival in the ALS model by targeting different mechanisms of neurode-generation (9–13). When given together, the combinations of minocycline and creatine, as well as celecoxib and creatine have enhanced benefit (14,15).

The number of agents that are being examined in the laboratory is increasing, but the low prevalence of ALS limits how many potential neuroprotective agents can be tested for efficacy in human trials, either individually or in combination. Consequently, more efficient phase II trial designs are needed to screen promising agents so that the few possible efficacy trials are conducted only with those agents most likely to succeed. We report the results of a multicenter phase II trial that examined the combinations of celecoxib-creatine and minocycline-creatine in ALS using an efficient selection paradigm (16).

Patients and methods

Patients

Eligible patients had a clinical diagnosis of possible, laboratory-supported probable, probable or definite ALS according to modified El Escorial criteria (17), were 21–85 years of age, had a forced vital capacity (FVC) greater than or equal to 60% of predicted, and had onset of weakness ≤5 years before enrollment. If patients were taking riluzole, they were on a stable dose for at least 30 days prior to enrollment. Women of childbearing potential were non-lactating, using an effective method of birth control, and had a negative pregnancy test. All participants signed informed consent approved by the individual institutional review boards.

Exclusion criteria were tracheostomy ventilation (or non-invasive ventilation >23 h/day); diagnosis of another neurodegenerative disease in addition to ALS; history of an unstable medical condition in the previous one year; history of systemic lupus erythematosus; history of congestive heart failure; a first degree relative with ALS; pregnancy, lactation, or inadequate use of birth control; allergy to minocycline, celecoxib, sulfonamides, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or creatine; renal disease (serum creatinine >1.5 for men, >1.2 for women); hepatic disease (serum aminotransferase or bilirubin >1.5 × normal); use of an investigational agent within 30 days of enrollment; or history of non-compliance with other experimental protocols.

Study design

This investigator-initiated, phase II, randomized, double-blind, selection trial was conducted at 17 centers in the United States, and could enroll up to 120 patients with ALS in two sequential pools of 60 patients each. Patients were randomized to one of two arms – minocycline-creatine or celecoxib-creatine. The total study length could have taken up to 24 months: four months for accrual and six months of follow-up per pool (20 months total), and four months for data analysis. Five of the scheduled patient evaluations were conducted in the center (baseline, months 1, 3, 5, 6) and two by telephone (months 2, 4). If a patient became too disabled to travel to the clinic for a scheduled incenter evaluation, the primary outcome measure was obtained by telephone (18).

Data on eligibility were collected at a screening visit. Randomization, which occurred at a baseline visit within 14 days of the screening visit, was stratified by center and by the disease rate of progression so as to enhance within-stratum patient homogeneity. An individual’s rate of progression was calculated by taking 48 minus the ALSFRS-R score at the screening visit divided by the time from symptom onset in months (19). Patients were randomized into slow or rapid strata based on whether their calculated rate of progression fell above or below 0.5 units/month, the median value from our clinic population (20). The Data Coordinating Center developed an online randomization system that automated protocol-specified interactions and information transmission among the site coordinators, principal investigator and pharmacy. Using this system, the principal investigator assessed each screened candidate for inclusion in the trial and assigned the stratum. Drug codes were provided by the system at the time of the baseline visit. Blinded treatment assignment reports were available to the pharmacy and to the statistician through the system, which also alerted the pharmacy when a site was low on drug supply.

Following randomization, participants were given either 10 g of creatine powder (tricreatine ascorbate, The Avicena Group Inc., California) plus minocycline (VA Cooperative Group, New Mexico) in 100-mg capsules twice each day, or the same dose of creatine plus celecoxib (Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, New York) in 400-mg capsules twice daily. The doses were chosen to balance safety as mandated by the U.S. FDA in approving the trial, and seeking doses for which there is evidence of CNS penetration (21,22). Minocycline and celecoxib were encapsulated in identical size white opaque capsules, which were packaged into high density polyethylene screwtop pharmacy bottles with seals and cotton. The bottles were filled according to the randomization assignment, and each bottle was labeled in a patient specific, double-blinded manner. Bottles and creatine packets were then placed into kits, with each kit being specific for one patient. All medications were used within the manufacturers’ expiry date.

The site investigators could temporarily reduce or discontinue the study combination if an adverse event occurred. A single drug holiday lasting not more than three weeks could be invoked at the site investigator’s discretion. If the adverse event was serious or resulted in elevated renal function (a rise in creatinine >35% above baseline), the study medication was stopped permanently. All patients received creatine; minocycline and celecoxib were administered in a double-blind fashion. No code break reports occurred during the study.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was change in function as measured by the change over six months in the the 48-point ALS Functional Rating Scale, Revised (ALSFRS-R) (23–28). The six-month decline for each individual was calculated by subtracting the six-month score from the baseline ALSFRS-R score. Every possible effort was made to obtain the six-month score for every patient. The six-month score was imputed for patients who died in less than six months by assigning it a value of zero. Secondary outcome measures, used to assess safety, comprised the following: changes in FVC (percent predicted) (29); the Single Item McGill Quality of Life (QoL) Scale (30); the Timed Up and Go Test (TUG) (31); death from any cause, tracheostomy, or chronic assisted ventilation; and the occurrence of adverse events, abnormal laboratory studies, or changes in the electrocardiogram (EKG). The EKG was assessed three times, the FVC and TUG were measured five times, the QoL scale monthly, and laboratory studies, including blood counts and chemistry as well as renal and liver function tests, were performed every two weeks. Serum riluzole levels were obtained from 14 patients at the baseline, month 1 and month 3 visits.

Data were collected on paper forms and entered by investigative staff at each site within 24 h of a patient’s visit into a secure web-based data entry system, using Scientific Web-based Information Management software. Automated error-checking programs were run by the Clinical Coordinating Center; the resulting queries were sent to the sites and resolved online. An independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board inspected unblinded data during the trial for safety. An independent safety monitor reviewed serious adverse events when they occurred, and monthly reports prepared by the data manager, summarizing all serious and minor adverse events. The trial had US Food and Drug Administration oversight.

Statistical analysis

Primary selection analysis

The primary objective of the trial was to select the better arm between the two in terms of the six-month decline in ALSFRS-R scores. The analysis used the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, comprising all patients who were randomized. After the first 60 patients completed six months of follow-up, the trial could be stopped if the difference in the mean decline in scores between the two arms was at least as large as 0.75 times the standard error of a single sample mean, i.e. sp/√30, where sp is the pooled sample standard deviation of individual ALSFRS-R declines from both arms. The combination inducing the smaller mean decline in ALSFRS-R would be selected. Otherwise, the trial would enroll a second pool for a total of 120 patients, after which the arm with the smaller mean decline would be selected. The sample size and stopping criterion were determined so that we could correctly select the better arm with at least 80% probability, assuming the true mean decline in the better arm was at least 1.16 points less than that of the inferior arm and that the standard deviation of an individual decline was 6.77 points. These design parameters were based on the historical control data from a randomized trial of gabapentin versus placebo (26), which had a combined-arm average decline in ALSFRS over six months of 5.82 and a standard deviation of 6.77. A true difference of 1.16 points corresponds to a 20% improvement over the historical control mean of 5.82 points.

Secondary futility analysis

The secondary objective of the trial called for a non-superiority or ‘futility’ test (32). The null hypothesis for the futility comparison stated that the selected treatment confers at least a 25% reduction in the mean six-month decline in ALSFRS-R compared to the historical control mean. The test was designed to be conducted sequentially. Specifically, if the selection stopping criterion was met after one pool, we would reject the null hypothesis for a treatment arm and conclude that the treatment was futile if its average decline was more than 0.75 times the historical control mean plus 1.91 times the standard error, i.e.:

where μ0 = 5.82 is the historical mean, X̄30 is the observed sample mean decline of the treatment arm based on a sample size of 30, and s.e.(X̄30) is the observed standard error (the square root of the treatment-specific sample variance of an individual observation divided by √30). The critical constant 1.911 is the upper 3.3rd percentile of the t-distribution with 29 degrees of freedom. If the selection stopping criterion was not met after the first pool, we would proceed to the second stage and enroll an additional 60 patients unless either of the arms was significantly futile at the nominal α=0.005 one-sided level, which was an interim stopping criterion for futility:

where the critical constant 2.756 is the upper 0.005th quantile of the t-distribution with 29 degrees of freedom. If the trial was stopped for neither selection nor futility after the first pool of 60 patients, a final futility analysis would be conducted after the second pool, wherein a treatment arm would be declared futile if its average decline was more than 0.75 times the decline of the historical controls plus 1.58 times the standard error:

where X̄60 is the sample mean based on the 60 patients from both pools, and 1.578 is the upper 6th percentile of the t-distribution with 59 degrees of freedom. The critical constants for the futility analysis (1.911, 2.756 and 1.578) were chosen to compensate for selection bias, so that the overall type 1 error level was no greater than 0.05 when one arm was 25% superior (i.e. with mean decline equal to 0.75μ0) and the other arm was the same as the historical control.

Statistical analyses of baseline and secondary endpoints

The treatment groups were compared at baseline for comparability. Continuous and discrete outcomes, FVC, QOL, TUG test and the number of adverse events, were compared between arms using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables such as occurrence of adverse events and abnormal laboratory tests were compared using Pearson’s χ2 test, or a Fisher’s exact test when an expected cell count was less than 5. For the secondary functional outcome measures, missing observations at month 6 were imputed by assigning the worst possible value (FVC=0, TUG=180, and QoL=0) to all those missing data due to death or weakness (for TUG only); missing values due to phone call or study personnel error were assigned the most recent valid observed value from a previous visit. Riluzole levels were compared between groups using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Results

Patients

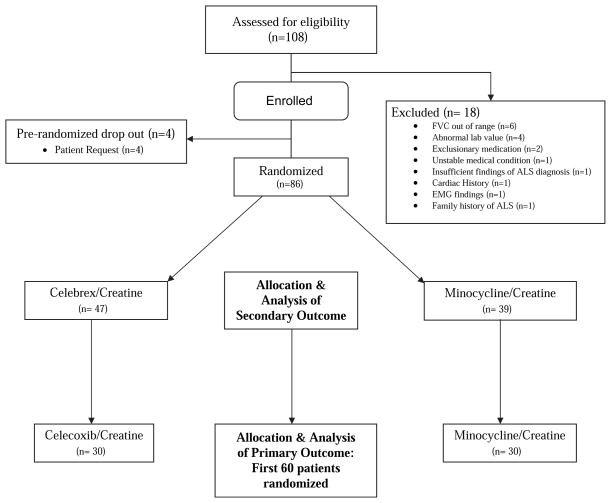

From July 2006 to September 2006, 86 patients were randomized to one of the two drug combinations (Figure 1). The first 60 patients constituted the selection criterion and futility analysis sample as planned for the primary outcome measure. An additional 26 subjects were randomized because of an unanticipated high rate of screening and recruitment. The results for the secondary outcome measures are given for both the initial 60 patients randomized in pool 1 and for the full set of 86 patients. There were 18 screening failures; the most common reasons were FVC less than 60% of predicted and abnormal laboratory value. Demographic and baseline characteristics were similar in both groups (Table I), including baseline ALSFRS-R and FVC values, rate of progression, and the number taking riluzole.

Figure 1.

The Consort E-Flowchart combination Drug Trial in ALS.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics.

| Primary analysis (n=60)

|

Secondary analysis (n=86)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocyline/Creatine | Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocyline/Creatine | |

| No. of patients randomized (%) | 30 (50.0) | 30 (50.0) | 47 (54.7) | 39 (45.3) |

| Sex, no. (% within drug group) | ||||

| Male | 23 (76.7) | 15 (50.0) | 36 (76.6) | 23 (59.0) |

| Female | 7 (23.3) | 15 (50.0) | 11 (23.4) | 16 (41.0) |

| Age at enrollment, years (Mean) (SD) | 55.43 (10.89) | 58.50 (13.24) | 55.62 (11.48) | 58.62 (12.87) |

| Race, no. (%) | ||||

| White | 26 (86.7) | 27 (90.0) | 41 (87.2) | 35 (89.7) |

| Black or African American | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 3 (6.4) | 1 (2.6) |

| Asian | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 2 (6.7) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (4.3) | 3 (7.7) |

| Hispanic ethnicity (race classified as Other for 5 and as White for 1): no. (%) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (4.8) | 4 (10.3) |

| Site of onset, no. (%) | ||||

| Arm | 11 (36.7) | 15 (50.0) | 18 (38.2) | 20 (51.3) |

| Leg | 12 (40.0) | 10 (33.3) | 16 (34.0) | 11 (28.2) |

| Bulbar | 7 (23.3) | 5 (16.7) | 13 (27.7) | 8 (20.5) |

| Progression rate, no. (%) | ||||

| Slow | 18 (60.0) | 17 (56.7) | 25 (53.2) | 23 (59.0) |

| Fast | 12 (40.0) | 13 (43.3) | 22 (46.8) | 16 (41.0) |

| ALSFRS-R: Mean (SD) | 38.73 (5.11) | 38.60 (4.59) | 38.79 (4.91) | 38.51 (4.77) |

| FVC: Mean percent predicted (SD) | 88.90 (13.64) | 94.07 (15.11) | 87.96 (15.02) | 92.08 (15.13) |

| TUG: Mean time (SD) | 20.54 (35.59) | 11.91 (5.89) | 19.89 (29.98) | 11.26 (5.24) |

| Mean number of days from symptom onset to enrollment (SD) | 734.10 (415.96) | 703.93 (401.12) | 650.72 (396.83) | 732.56 (381.90) |

| On riluzole, no. (%) | 20 (66.7) | 21 (70.0) | 28 (59.6) | 27 (69.2) |

| Weight, pounds: Mean (SD) | 173.47 (24.52) | 174.17 (33.19) | 177.66 (32.21) | 171.77 (30.95) |

ALSFRS-R: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale, Revised; FVC: Forced Vital Capacity.

Twelve patients in the celecoxib-creatine group and 10 in the minocycline-creatine group discontinued treatment prematurely. Patients who stopped taking drug continued to undergo the scheduled monthly evaluations. Based on pill counts, the celecoxib-creatine group had a mean treatment adherence of 85% compared to 92% in the minocycline-creatine group. There were no dropouts during the trial; all randomized patients reached the end of study by virtue of completion of six months of follow-up or death. The final patient completed the trial in March 2007.

Primary analysis: selection based on the ALSFRS-R

Of the first 60 patients, 58 had the ALSFRS-R score measured at their six-month follow-up; two patients died and were assigned an ALSFRS-R score of zero as their six-month outcome. The mean declines in ALSFRS-R were 5.27 (SD=5.54, 95% CI 3.3–7.3) in the celecoxib-creatine arm and 6.47 (SD=9.14, 95% CI 3.2–9.7) in the minocycline-creatine arm. The absolute difference between the two sample means was 1.200. The pooled sample standard deviation of individual ALSFRS-R declines was 7.556, and the numerical selection criterion was therefore equal to 0.75×7.556/√30=1.035. Thus, the absolute mean difference between the arms exceeded the threshold in the selection stopping criterion.

Secondary futility analyses

Because the selection stopping criterion was met, we used

as the criterion for the futility test. For the celecoxib-creatine arm,

so we did not reject the null hypothesis of superiority. Similarly, the futility criterion was not met for the minocycline-creatine arm.

Analyses of secondary outcome measures (Tables II and III)

Table II.

Secondary functional outcomes: FVC, TUG, QoL.

| Outcome measure | Baseline Mean

|

6-month Mean

|

Mean change in scores

|

p-value Wilcoxon rank-sum test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis (n=60) | Celecoxib/Creatine (n=30) | Minocycline/Creatine (n=30) | Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocycline/Creatine | Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocycline/Creatine | |

| Primary analysis (n=60) | |||||||

| Mean FVC (SD) | 88.90 (13.64) | 94.07 (15.11) | 76.57 (24.81) | 76.00 (31.27) | −12.33 (15.88) | −18.07 (24.75) | 0.482 |

| Mean TUG (SD) n=46 | 20.54 (35.59) | 11.91 (5.89) | 37.27 (56.10) | 36.00 (60.44) | 16.73 (44.53) | 24.09 (57.35) | 0.201 |

| Mean QoL (SD) | 8.20 (1.61) | 7.43 (2.06) | 6.53 (2.16) | 5.87 (2.79) | −1.67 (2.28) | −1.57 (2.87) | 0.589 |

| Secondary analysis (n=86) | Celecoxib/Creatine (n=47) | Minocycline/Creatine (n=39) | Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocycline/Creatine | Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocycline/Creatine | |

| Mean FVC (SD) | 87.96 (15.02) | 92.08 (15.13) | 72.68 (27.23) | 70.51 (33.75) | −15.28 (18.09) | −21.56 (27.02) | 0.342 |

| Mean TUG (SD) | 19.89 (29.98) | 11.26 (5.24) | 53.13 (69.15) | 51.16 (72.43) | 33.24 (61.27) | 39.90 (70.53) | 0.508 |

| Mean QoL (SD) n=72 | 7.83 (1.85) | 7.31 (2.08) | 6.21 (2.47) | 5.72 (3.02) | −1.62 (2.39) | −1.59 (2.90) | 0.728 |

FVC: Forced Vital Capacity; TUG: Timed Up and Go Test; QoL: Quality of Life. Fourteen participants were missing the baseline TUG values and the month 6 values and so were excluded from these analyses.

Table III.

Number (percent) of patients with ≥1 adverse events by body system in which event occurred.

| Primary analysis (n=60) | Serious adverse events

|

Non-serious adverse events

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body system | Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocycline/Creatine | p-value for χ2 | Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocycline/Creatine | p-value for χ2 |

| Cardiovascular | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 1.000a | 3 (10.0) | 2 (6.7) | 1.000a |

| Dermatological | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (50.0) | 10 (33.3) | 0.190 | |

| Ears, Nose and Throat | NA | NA | 13 (43.3) | 10 (33.3) | 0.426 | |

| Endocrine/metabolic | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) | 0.492a | |

| Eyes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (30.0) | 5 (16.7) | 0.222 | |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 (3.3) | 2 (6.7) | 1.000a | 19 (63.3) | 21 (70.0) | 0.584 |

| Genitourinary | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (33.3) | 7 (23.3) | 0.390 | |

| Hematological | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000a | |

| Musculoskeletal | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.3) | 1.000a | 14 (46.7) | 12 (40.0) | 0.602 |

| Neurological | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.3) | 6 (20.0) | 0.488 | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (23.3) | 7 (23.3) | 1.000 | |

| Psychological | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.3) | 9 (30.0) | 0.117 | |

| Respiratory | 1 (3.3) | 2 (6.7) | 1.000a | 6 (20.0) | 3 (10.0) | 0.472a |

| Total | 5 (16.7) | 5 (16.7) | 1.000 | 29 (96.7) | 30 (100.0) | 1.000a |

| Mean number of AEs per person (SD) | 0.23 (0.57) | 0.37 (0.89) | 0.873b | 5.33 (3.89) | 5.00 (2.92) | 0.994b |

| Cardiovascular | 2 (4.3) | 2 (5.1) | 1.000a | 7 (14.9) | 2 (5.1) | 0.174a |

| Dermatological | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (48.9) | 12 (30.8) | 0.088 | |

| Ears, Nose and Throat | NA | NA | 19 (40.4) | 12 (30.8) | 0.353 | |

| Endocrine/metabolic | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.1) | 0.203a | |

| Eyes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (23.4) | 5 (12.8) | 0.209 | |

| Gastrointestinal | 2 (4.3) | 2 (5.1) | 1.000a | 27 (57.4) | 28 (71.8) | 0.168 |

| Genitourinary | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (27.7) | 10 (25.6) | 0.833 | |

| Hematological | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000a | |

| Musculoskeletal | 3 (6.4) | 1 (2.6) | 0.623a | 21 (44.7) | 16 (41.0) | 0.733 |

| Neurological | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (12.8) | 7 (17.9) | 0.504 | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0.453a | 10 (21.3) | 8 (20.5) | 0.931 |

| Psychological | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (12.8) | 11 (28.2) | 0.073 | |

| Respiratory | 2 (4.3) | 4 (10.3) | 0.254a | 11 (23.4) | 4 (10.3) | 0.110 |

| Total | 9 (19.1) | 8 (20.5) | 0.874 | 45 (95.7) | 39 (100.00) | 0.498a |

| Mean number of AEs per person (SD) | 0.30 (0.69) | 0.41 (0.88) | 0.760b | 4.98 (3.44) | 4.67 (2.88) | 0.814b |

Fisher’s exact test due to expected cell counts <5.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

While the deterioration was slightly worse in the minocycline-creatine group for FVC and TUG, both in the initial 60 patients and the total 86 patients, the differences did not reach statistical significance for these measures or for QoL. Of the initial 60 patients, two in the minocycline-creatine group died and 58 patients completed the trial. Of the entire 86 patients enrolled, 35 patients completed the trial and four patients died in the minocycline-creatine group, and 46 patients completed the trial with one death in the celecoxib-creatine group (p=0.16 for the difference in death rate between groups, using Fisher’s exact test).

There were no statistically significant differences in the numbers of patients affected by serious adverse events (SAE) or non-serious adverse events (NSAE) between groups (Table III). SAE were most commonly reported in the respiratory system. NSAE most commonly occurred in the gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal and dermatologic systems, with the latter reaching a trend toward more frequent occurrence in the celecoxib-creatine group (n=86). When examining specific adverse events (Table IV), rash occurred more frequently in the celecoxib-creatine arm (n=86), and depression as well as constipation occurred significantly more often in the minocycline-creatine group.

Table IV.

Number (%) of individuals with specific non-serious adverse events for those events reported by at least eight (≈10%) of the participants.

| Specific event | Primary analysis (n=60)

|

Secondary analysis (n=86)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocycline/Creatine | p-value for χ2 | Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocycline/Creatine | p-value for χ2 | |

| Dermatological | ||||||

| Dry skin | 2 (6.7) | 4 (13.3) | 0.671a | 4 (8.5) | 6 (15.4) | 0.501a |

| Rash | 7 (23.3) | 1 (3.3) | 0.052a | 10 (21.3) | 1 (2.6) | 0.010a |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||||

| Fall | 11 (36.7) | 7 (23.3) | 0.260 | 14 (29.8) | 10 (25.6) | 0.670 |

| Muscle ache or pain | 3 (10.0) | 4 (13.3) | 1.000a | 4 (8.5) | 5 (12.8) | 0.726a |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||

| Constipation | 4 (13.3) | 9 (30.0) | 0.117 | 4 (8.5) | 10 (25.6) | 0.032 |

| Diarrhea | 9 (30.0) | 5 (16.7) | 0.222 | 16 (34.0) | 9 (23.1) | 0.265 |

| Nausea | 4 (13.3) | 9 (30.0) | 0.117 | 5 (10.6) | 10 (25.6) | 0.068 |

| Psychological | ||||||

| Depression | 1 (3.3) | 8 (26.7) | 0.026a | 2 (4.3) | 9 (23.1) | 0.020 |

| Other | ||||||

| Fatigue | 4 (13.3) | 4 (13.3) | 1.000a | 4 (8.5) | 5 (12.8) | 0.726a |

| Clinically abnormal serum creatinine | 3 (10.0) | 2 (6.7) | 1.000a | 4 (8.5) | 4 (10.3) | 1.00a |

Fisher’s exact due to small expected cell count (<5).

Eight patients had clinically significant elevations in serum creatinine, but the change in this value or in other laboratory findings was not significantly different between groups (Table V). When the study drugs were stopped, the creatinine levels normalized. Serum riluzole levels were measured in five patients in the celecoxib-creatine arm and nine patients in the minocycline-creatine arm. The median change in riluzole concentrations did not differ between groups either at month 1 (celecoxib-creatine=8.2 ng/ml, minocycline-creatine=6.3 ng/ml; p=0.57 for the difference between groups) or at month 3 (celecoxib-creatine=6.3 ng/ml, minocycline-creatine=2.9 ng/ml; p=0.79).

Table V.

Number (%) of patients with abnormal laboratory studies.

| Primary analysis (n=60) | Baseline (n=60)

|

At any follow-up visit (n=60)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab name | Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocyline/Creatine | p-value for χ2 | Celecoxib/Creatine | Minocyline/Creatine | p-value for χ2 |

| WBC | 4 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.112a | 6 (20.0) | 4 (13.3) | 0.488 |

| Hematocrit | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 1.000a | 5 (16.7) | 3 (10.0) | 0.706a |

| Platelets | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000a | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 1.000a |

| BUN | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (23.3) | 4 (13.3) | 0.317 | |

| Cr >35% change from baseline | NA | NA | 9 (30.0) | 7 (23.3) | 0.559 | |

| Cr abnormal (based on gender-specific ranges) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (16.7) | 8 (26.7) | 0.347 | |

| AST | 5 (16.7) | 2 (6.7) | 0.424a | 12 (40.0) | 10 (33.3) | 0.592 |

| ALT | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.3) | 1.000a | 9 (30.0) | 7 (23.3) | 0.559 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | 1.000a | 4 (13.3) | 5 (16.7) | 1.000a |

| Total bilirubin | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.3) | 1.000a | 3 (10.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0.612a |

| Any laboratory test | 11 (36.7) | 5 (16.7) | 0.080 | 25 (83.3) | 24 (80.0) | 0.739 |

| Secondary analysis (n=86) | Baseline (n=86) | At any follow-up visit (n=85) | ||||

| WBC | 5 (10.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0.215a | 8 (17.4) | 5 (12.8) | 0.560 |

| Hematocrit | 4 (8.5) | 2 (5.1) | 0.685a | 8 (17.4) | 5 (12.8) | 0.560 |

| Platelets | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000a | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.6) | 1.000a |

| BUN | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (23.9) | 4 (10.3) | 0.100 | |

| Cr >35% change from baseline | NA | NA | 10 (21.7) | 11 (28.2) | 0.491 | |

| Cr abnormal (based on gender-specific ranges) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (13.0) | 11 (28.2) | 0.082 | |

| AST | 7 (14.9) | 3 (7.7) | 0.337a | 15 (32.6) | 11 (28.2) | 0.661 |

| ALT | 4 (8.5) | 1 (2.6) | 0.371a | 14 (30.4) | 10 (25.6) | 0.625 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.6) | 1.000a | 4 (8.7) | 6 (15.4) | 0.502a |

| Total bilirubin | 4 (8.5) | 1 (2.6) | 0.371a | 5 (10.9) | 1 (2.6) | 0.212a |

| Any laboratory test | 16 (34.0) | 8 (20.5) | 0.164 | 37 (78.7) | 31 (79.5) | 0.931 |

Fisher’s exact test.

ALT: serum alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; Cr: serum creatinine; WBC: white blood cell count.

Discussion

The purpose of this trial was to determine which of two drug combinations best slowed deterioration in the ALSFRS-R, and whether the selection trial design could be an effective screening method for potential therapies in ALS. Treatments strong enough to prevent deterioration or reverse symptoms in ALS might be identified only after the specific causes of the disorder are found. In the meantime, researchers target mechanisms of cell death that occur downstream from the inciting event. Unfortunately, trials of agents that impact a single mechanism of neurodegeneration have thus far been largely negative; it has been over 10 years since the last clearly positive drug trial in ALS, and different ways to select and utilize interventions are needed.

One approach is to combine therapies, wherein targeting different and multiple mechanisms of neurodegeneration might be more effective than using single agents alone. There are several ways to combine therapy. One is to identify an agent with a positive effect in humans and then test another agent in combination with it. This approach has not yet been helpful in trials that used riluzole as the effective agent (26,28,33–35). Another route is to combine agents in human trials once scientific justification has been established by showing additive effects in the laboratory.

We chose the latter course, studying the combinations of minocycline-creatine and celecoxib-creatine because they are the only agents so far shown to have evident additive properties in blinded placebo-controlled trials in the murine model. Each of the drugs individually has meaningful neuroprotective effects in different models of neurodegeneration. Minocycline reduces pro-apoptotic and pro-inflammatory enzyme activation (9–11), creatine buffers cellular energy supplies in mitochondria (12,36), and celecoxib inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 as well as reduces prostaglandin-induced release of glutamate (13,37). When combined in the ALS model, these agents reduce neurodegeneration and prolong survival more than when given alone. In one murine study, minocycline extended survival 13% more than placebo, creatine 12%, and the combination 25% (14), and in a separate study, creatine extended survival 18% more than placebo, celecoxib 19%, and the combination 29% (15). The large therapeutic benefit of these combinations of agents on survival in transgenic mice provides scientific evidence that using combined therapies may be the currently most expedient means of improving the course of ALS.

To our knowledge, this was the first time the phase II selection trial design was used to select a potential therapy in ALS. The selection trial allows the study of groups of medications with reduced sample size, selecting a treatment based on predefined procedures that have a high probability of correct selection when one treatment is truly better than the other, and can be used to compare different therapies or different dosages of a single therapy. Our trial design selects the better treatment with 80% probability if one truly achieves a 20% advantage over the other. In that case, the group sequential design allows for stopping the trial after one pool with 67% probability, as it did in our study. Even if the better combination reduces the decline in ALSFRS-R by less than 20%, the selection procedure still identifies the better combination more often than not and also stops after one pool more often than not. The design was more efficient than standard phase II trials because it studied multiple active treatment arms without a placebo group, formal significance testing was declared a secondary objective to the selection goal, and group sequential analysis allowed early termination. Futility testing then determined whether the data could reject a hypothesis of substantial superiority. In the event that a combination could not support the superiority hypothesis, we would have been able to conclude futility for one or both treatments with at most only 120 patients. We were able to close the trial early and select the celecoxib-creatine arm, which had a smaller mean decline and was non-futile compared to the historical control group. These decisions were made along with the comparable safety data of the combinations. The entire trial, including the enrollment, evaluation and analysis phases, took just 13 months to complete.

We highlight some aspects of the methodology: 1) The design does not select an efficacious therapy, but selects the better performing of two treatment arms. 2) The primary analysis does not involve a comparison of the result with historical controls in a non-futility analysis, but rather a comparison of two drug combinations in the current trial. Secondary analyses considered performance of each combination compared with historical control data. In the context of the primary analysis, this secondary analysis is relevant to the celecoxib/creatine arm.

The primary outcome measure for the trial was the change in the ALSFRS-R, which reduced the number of dropouts because it was administered over the telephone when patients became too sick to travel to the clinic. There were, in fact, no dropouts, a probable first in a trial of ALS which maximized power and minimized bias. While not the case in every study, most indicate that the ALSFRS-R is a strong predictor of survival which, coupled with its ease of administration and ability to reduce dropout, makes it the most dependable surrogate for survival in early phase trials (24–26,28,38,39). Another feature of this trial was the stratification by rate of progression at enrollment. The site of onset and riluzole use may each impart modest outcome effects, but, until clear clinical subgroups are defined, the rate of progression within an individual may be the most important predictor of outcome (19,20), and proved to be a readily identifiable variable in this trial. Randomization within strata defined by this predictor helped to assure balanced assignment between the combination therapies within each stratum.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the results of the trial cannot and should not be construed as proof of efficacy. They are, however, consistent with the results of a recent phase III trial in which patients assigned to minocycline had more severe deterioration in the ALSFRS-R than patients assigned to placebo (28). Furthermore, each of the three drugs individually has failed a phase III trial in ALS. Minocycline caused patients to have a faster rate of progression, and creatine and celecoxib had no effect in recent trials (28,40–42), although the dosages used for creatine were lower than in our trial. Stronger agents are needed, but a failure individually does not equate with failure in combination. Secondly, our trial did not randomize patients to a placebo group, instead comparing two active arms for the selection procedure. This feature was appealing to patients; enrollment was so robust that the study overenrolled the first pool in three months instead of the planned four months. Absence of a placebo group may also have reduced the dropout rate, but it prevented a direct comparison to a concurrent control group for the primary and safety outcome measures, and so the usual cautions apply, principally that the sample under study somehow differs from the historical control sample, and therefore that a placebo group in the current trial would have been different from the historical controls (32). We used historical data from a phase III ALS trial (26), but only to produce a definition of absolute superiority in the futility analysis, and we used the same enrollment criteria as that trial did to limit differences. Thirdly, our study did not compare different doses of the combinations, and budgetary limitations prevented formal sampling of blood and spinal fluid drug levels. While this trial piloted the design, it was not a dose-ranging study. We emphasize the importance of correct dose selection in early phase trials before proceeding to phase III trials. As reported previously, this design can be coupled with a phase I component to efficiently select doses (16). We found no significant changes in serum riluzole levels due to either combination, but power was limited for these assessments. Finally, some patients had modest elevations in serum creatinine levels, presumably due to the high dose of creatine (43), but future studies should include an assessment of creatinine clearance to ensure that renal insufficiency is not caused by the drugs.

We emphasize that the utility of the selection approach is not to conclude significance or efficacy. Rather, the goal is to prioritize different possible regimens for further testing, i.e. to select the best performing from among currently available potential neuroprotective agents. It is true that if no available agent is effective, then this design will not produce an effective treatment for further testing. However, if one or two drugs are effective, the standard approach of opinion-based testing of one drug at a time in long large trials makes it unlikely that a truly effective therapy will be identified. The selection screening process increases the likelihood that efficacy trials are performed with the agents most likely to succeed. A converse interpretation is that the non-selected potential agents, in this case the minocycline combination, can be excluded from further consideration, a reasonable conclusion, particularly in light of the results of the phase III trial and the difference in efficiency between the two trials. It would be a meaningful benefit to the field if ineffective drugs could be identified as such in screening trials of 60 patients conducted in one year rather than proceeding with them to efficacy studies of hundreds of patients conducted over multiple years, as is still the current approach in the field.

Despite advances in understanding its pathogenesis, ALS remains an untreatable disease. Given the myriad mechanisms of neurodegeneration, it is possible that combinations of agents, targeting different processes, will be necessary for a meaningful effect. To our knowledge, this was the first time the selection paradigm was used to select a promising combination. According to the primary and secondary analyses, there is no evidence to preclude celecoxib/creatine from further study. The design can lead to future phase II selection trials testing several medications simultaneously, thereby improving the speed and efficiency of drug screening in ALS.

Acknowledgments

The trial was supported by an ALSA TREAT ALS grant, MDA Wings Over Wall Street, Avicena Corporation, Carol and Bill Spina and Ross Bowen Funds, and Ride for Life. Dr. Gordon received $30,000 from Avicena Group, Inc to support the trial.

Appendix 1: Study personnel

Performance and Safety Monitoring Board: C. Armon, R. Conwit, Y. Palesh, K. Reilly Powderly; Steering Committee: J. Florence, J. Rowin, K. Boylan, P.H. Gordon, T. Mozaffar, P. Kelkar, R. Tandan; ALSA Program Management: L. Bruijn; Clinical Coordinating Center: P.H. Gordon, R.B. MacArthur, C. Doorish, K. Bednarz, M. Lewis, S. Chew, A. Altincatal; Data Coordinating Center: Y.K. Cheung, H. Andrews, B. Levin, E. Kelvin, M. Garcia; Safety Monitor: D. Chad.

California Pacific Medical Center: R. G. Miller, J. Katz, C. Madison, T. Santos, G. Kushner; Columbia University: P.H. Gordon, H. Mitsumoto, P. Kaufmann, J. Bhatt, C. Doorish, K. Bednarz, S. Chew, J. Montes, M. Lewis, R.B. MacArthur, A. Altincatal; Duke University: R. Bedlack, P. Burke, K. Grace; Mayo Clinic Jacksonville: K. Boylan, A. Evans, K. Overstreet; Mayo Clinic Rochester: E. J. Sorenson, S. Paxton, S. Klingerman; Medical College of Georgia: M. Rivner, J. Iyer, L. Edmonds; Oregon Health and Science University: J.S. Lou, S. Johnson; Phoenix Neurological Associates: D. Saperstein, T. Levine, K. Clarke, L. Flynn; University of California Irvine: T. Mozaffar, K. Lee, R. Karayan, V. Martin, S. Rao; University of California Los Angeles: M. Graves, M. Wiedau-Pazos, R. Alvarez, J. Albu; University of Kansas: R. Barohn, A. Dick, A. McVey, M. Walsh, L. Herbelin, V. Watts, P. Cagle; UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, NJ: J. Belsh, B. Belsh, M. Mertz; University of New Mexico: J. Chapin, J. Boyle; University of Pennsylvania: L.F. McCluskey, M. Kelley, L. Klenke-Borgmann, L. Elman; University of Vermont: R. Tandan, A. Quick, S. Lenox, C. Potter, M. Jones; Washington University: A. Pestronk, J. Florence, B. Abrams, C. Wulf.

The trial was also supported in part by the following GCRC grants: NIH MO1 RR023940 supporting the University of Kansas Medical Center; NIH UL1RR024992 supporting the Center for Applied Research Sciences at the Washington University School of Medicine; NIH 5M01RR 00827-29 supporting the University of California Irvine; and NIH RR-00109 supporting the University of Vermont.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Rowland LP, Shneider NA. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1688–700. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menzies FM, Ince PG, Shaw PF. Mitochondrial involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurochemistry International. 2002;40:543–51. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guegan C, Vila M, Rosoklija G, Hays AP, Przedborski S. Recruitment of the mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic pathway in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6569–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06569.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothstein JD, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW. Decreased glutamate transport by the brain and spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. New Engl J Med. 1992;236:1464–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205283262204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshihara T, Ishigaki S, Yamamoto M, Liang Y, Niwa J, Takeuchi H, et al. Differential expression of inflammation-and apoptosis-related genes in spinal cords of a mutant SOD1 transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem. 2002;80:158–67. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall ED, Oostveen JA, Gurney ME. Relationship of microglial and astrocytic activation to disease onset and progression in a transgenic model of familial ALS. Glia. 1998;23:249–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199807)23:3<249::aid-glia7>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–5. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacomblez L, Bensimon G, Leigh PN, Guillet P, Meininger V. Dose-ranging study of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/Riluzole Study Group II. Lancet. 1996;347:1425–31. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu S, Stravrovskaya IG, Drozda M, Kim BY, Ona V, Li M, et al. Minocycline inhibits cytochrome c release and delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. Nature. 2002;417:74–8. doi: 10.1038/417074a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Bosch L, Tillkin P, Lemmens G, Robberecht W. Minocycline delays disease onset and mortality in a transgenic model of ALS. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1067–70. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200206120-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kriz J, Nguyen M, Julien J. Minocycline slows disease progression in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:268. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klivenyi P, Ferrante RJ, Matthews RT, Bogdanov MB, Klein AM, Andreassen OA, et al. Neuroprotective effects of creatine in a transgenic animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature Med. 1999;5:347–50. doi: 10.1038/6568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drachman DB, Frank K, Dykes-Hoberg M, Teismann P, Almer G, Przedborski S, et al. Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibition protects motor neurons and prolongs survival in a transgenic mouse model of ALS. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:771–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.10374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang W, Narayanan M, Friedlander RM. Additive neuro-protective effects of minocycline with creatine in a mouse model of ALS. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:267–70. doi: 10.1002/ana.10476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klivenyi P, Kiaei M, Gardian G, Calingasan NY, Beal MF. Additive neuroprotective effects of creatine and cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;88:576–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung YK, Gordon PH, Levin B. Selecting promising ALS therapies in clinical trials. Neurology. 2006;67:1748–51. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244464.73221.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL for the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1:557–60. doi: 10.1080/146608200300079536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Florence JM, Moore D, Spitalny GM, Miller RG, Gordon PH. Performance of in-person vs. phone ALSFRS-R in a randomized, controlled phase III clinical trial of minocycline in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2006;7(Suppl 1):116. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura F, Fujimura C, Ishida S, Nakajima H, Furutama D, Uehara H, et al. Progression rate of ALSFRS-R at time of diagnosis predicts survival time in ALS. Neurology. 2006;66:265–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194316.91908.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon PH, Cheung YK. Progression rate of ALSFRS-R at time of diagnosis predicts survival time in ALS. Neurology. 2006;67:1314–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000243812.25517.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saivin S, Hovin G. Clinical pharmacokinetics of doxycycline and minocycline. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1988;15:355–66. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198815060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jhee SS, Frackiewicz EJ, Tolbert D. A pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and safety study of celecoxib in subjects with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical research and regulatory affairs. Marcel Dekker. 2004;21:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- 23.The ALS CNTF Treatment Study (ACTS) Phase I-II Study Group. The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale. Assessment of activities of daily living in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:141–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N. Performance of the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale (ALSFRS) in multicenter clinical trials. J Neurol Sci. 1997;152(Suppl 1):S1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, Fuller C, Hilt D, Thurmond B, et al. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase II/III) J Neurol Sci. 1999;169:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller RG, Moore D, Barohn RJ, Gelinas DF, Dronsky V, Mendoza M, et al. Phase II/III randomized trial of gabapentin in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2001;56:843–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scelsa SN, MacGowan DJ, Mitsumoto H, Imperato T, LeValley AJ, Liu MH, et al. A pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of indinavir in patients with ALS. Neurology. 2005;64:1298–300. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000156913.24701.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon PH, Moore DH, Miller RG, Florence JM, Verheijde JL, Doorish C, et al. Efficacy of minocycline in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase III randomized trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:1045–53. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.A Controlled trial of recombinant methionyl human BDNF in ALS: The BDNF Study Group (Phase III) Neurology. 1999;52:1427–33. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robbins RA, Simmons Z, Bremer BA, Walsh SM, Fischer S. Quality of life in ALS is maintained as physical function declines. Neurology. 2001;56:442–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montes J, Cheng B, Diamond B, Doorish C, Mitsumoto H, Gordon PH. The Timed Up and Go test: predicting falls in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2007;8:292–5. doi: 10.1080/17482960701435931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin B. The utility of futility. Stroke. 2005;36:2331–2. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185722.99167.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cudkowicz ME, Shefner JM, Schoenfeld DA, Brown RH, Jr, Johnson H, Qureshi M, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2003;61:456–64. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.4.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller R, Bradley W, Cudkowicz, Hubble J, Meininger V, Mitsumoto H, et al. Phase II/III randomized trial of TCH346 in patients with ALS. Neurology. 2007;69:776–84. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000269676.07319.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meininger V, Bensimon G, Bradley WR, Brooks B, Douillet P, Eisen AA, et al. Efficacy and safety of xaliproden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: results of two phase III trials. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2004;5:107–17. doi: 10.1080/14660820410019602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellis AC, Rosenfeld J. The role of creatine in the management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other neurodegenerative disorders. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:967–80. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418140-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakayama M, Uchimura K, Zhu R, Nagayama T, Rose ME, Stetler RA, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition prevents delayed death of CA1 hippocampal neurons following global ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10954–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufmann P, Levy G, Thompson JL, Delbene ML, Battista V, Gordon PH, et al. The ALSFRS-R predicts survival time in an ALS clinic population. Neurology. 2005;64:38–43. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000148648.38313.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gordon PH, Cheng B, Montes J, Doorish C, Albert SM, Mitsumoto H. Outcome measures for early phase clinical trials. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2007;8:270–3. doi: 10.1080/17482960701547958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groeneveld GJ, Veldink JH, van der Tweel I, Kalmijn S, Beijer C, de Visser M, et al. A randomized sequential trial of creatine in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:437–45. doi: 10.1002/ana.10554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shefner JM, Cudkowicz ME, Schoenfeld D, Conrad T, Taft J, Chilton M, et al. A clinical trial of creatine in ALS. Neurology. 2004;63:1656–61. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142992.81995.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cudkowicz ME, Shefner JM, Schoenfeld DA, Zhang H, Andreasson KI, Rothstein JD, Drachman DB. Trial of celecoxib in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:22–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.20903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hersch SM, Gevorkian S, Marder K, Moskowitz C, Feigin A, Cox M, et al. Creatine in Huntington’s disease is safe, tolerable, bioavailable in brain and reduces serum 8OH2’dG. Neurology. 2006;66:250–2. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194318.74946.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]