Abstract

Radiant skin and hair are universal indicators of good health. It was recently shown that feeding of probiotic bacteria to aged mice rapidly induced youthful vitality characterized by thick lustrous skin and hair, and enhanced reproductive fitness, not seen in untreated controls. Probiotic-treated animals displayed integrated immune and hypothalamic-pituitary outputs that were isolated mechanistically to microbe-induced anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 and neuropeptide hormone oxytocin. In this way probiotic microbes interface with mammalian physiological underpinnings to impart superb physical and reproductive fitness displayed as radiant and resilient skin and mucosae, unveiling novel strategies for integumentary health.

Keywords: probiotics, inflammation, regulatory T cells, Lactobacillus reuteri

1. Introduction

Skin and mucosal surfaces of mammals are populated by millions of bacteria (Gordon, 2012; Nicholson et al., 2012; Lee and Mazmanian, 2010; McNulty et al.; Chinen and Rudensky, 2012; Hooper et al., 2012; Maynard et al., 2012). Disruption of the normal balance between resident microbial communities is associated with a wide array of allergic, autoimmune, metabolic, and neoplastic pathologies (Clemente et al., 2012; Fujimura et al., 2010; Neish, 2009; Noverr and Huffnagle, 2004; Tlaskalova-Hogenova et al., 2011). Mechanistically, microbes and their metabolites interact with immunological (Chow and Mazmanian, 2009; Chung et al., 2012; Hooper et al., 2012; Maynard et al., 2012), metabolic (Clemente et al., 2012; Nicholson et al., 2012; Shanahan, 2012; Young, 2012) and neuroendocrine pathways (Bravo et al., 2011; Foster and McVey Neufeld, 2013; Nicholson et al., 2012) that modify stress-related responses in the skin through a gut-brain-skin axis (Arck et al., 2010). As a result, modifying the host microbiota by using dietary prebiotic supplements or probiotic organisms is now an emerging therapeutic and overall health-promoting modality (Floch et al., 2011; Gordon, 2012; Litonjua and Weiss, 2007; Ravel et al., 2011; Shanahan, 2012; Young, 2012). Data from both mice and humans suggest that supplementation with probiotic bacteria has many beneficial effects in the skin (Arck et al.; Chapat et al., 2004; Floch et al., 2011; Gueniche et al., 2010; Gueniche et al., 2006; Krutmann, 2009). Similar microbial organisms dominate under natural conditions of infancy and peak fertility in many animal species (Clemente et al., 2012; Fujimura et al., 2010; Neish, 2009), making them logical choices to promote effects of youthful appeal. The importance of probiotic effects on skin health and radiance extends beyond obvious cosmetic aspects to systemic host health and well-being.

2. Beneficial gut microbes induce quantifiable changes in skin and hair quality

Dramatically improved skin and mucosal health was recently discovered in animal models consuming a probiotic-containing yogurt (Levkovich et al., 2013). Differences in hair luster and density were observed within days after feeding of a probiotic-enriched diet to C57BL/6 strain mice, whereas matched animals receiving control chow alone had duller fur or exhibited alopecia and dermatitis. Microscopy–assisted histomorphometry revealed that consumption of the probiotic-rich diet led to significantly thicker skin and follicular anagenesis, according to the well-established histological parameters of hair follicle development (Muller-Rover et al., 2001; Plikus and Chuong, 2008; Schneider et al., 2009; Sundberg et al., 2005). Likewise, mice fed a purified preparation of human-milk-origin Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC PTA 6475 (hereafter referred to as ‘L. reuteri’), without any yogurt supplementation, also displayed the skin glow and exuberant hair growth. This showed that probiotic microbes, rather than the milk protein or nutrients such as vitamin D (Litonjua and Weiss, 2007), were responsible for stimulating features of dermal thickening, folliculogenesis, and sebocytogenesis comprising the healthy glow effect (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dietary Lactobacillus reuteri induce a “glow of health”.

(A) Aged mice consuming probiotics develop shiny fur readily detectable by sensory and mechanical methods of fur lustre assessment. The same mice show a remarkably accelerated hair re-growth capacity after shaving when compared to control mice. (B) The skin of aged adult C57BL/6 mice with probiotic-induced radiant fur is thicker and shows increased hair follicle anagenesis. Numbers on the y-axis of bar graphs represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. (C) Haematoxylin and eosin staining; bars = 250 mm.

Highly significant differences observed in light reflectivity on hair coat were quantifiable by sensory or mechanical evaluations (Levkovich et al., 2013). Female animals, in particular, had especially shiny hair coinciding with an acidic mucocutaneous pH (Figure 2B). Interestingly, syngeneic mutant mice lacking the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-10 failed to exhibit the glistening hair after eating probiotics, and also had alkaline rather than acidic pH levels. Thus, cytokine IL-10 and immune competency to control host inflammation and pH levels were found to be important for a healthy integument (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Dietary Lactobacillus reuteri induce a “glow of health”.

The Lactobacillus reuteri-induced ‘glow of health’ attributes, including the follicular anagenic shift, depend upon the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, and can be recapitulated by the depletion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17. Numbers on the y-axis of bar graphs represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. (B) Mucocutaneous hyperacidity (a significant decrease in mucocutaneous pH) coincides with shinier hair in probiotic-fed mice. Numbers on the y-axis of bar graphs represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. * = P<0.05; ** = P<0.01; *** = P<0.0001.

Mice of differing genetic backgrounds, for example outbred Swiss mice with white fur, also exhibited dermal thickening, folliculogenesis, and sebocytogenesis, comparable to that seen in C57BL/6 strain animals (Levkovich et al., 2013), providing evidence of a more universal health benefit after consuming probiotics. Sleek pellage arising in white-haired mice yielded an opalescent effect attributed to increased sebum, displaying a colorful halo effect perceptible to the naked eye.

Interestingly, consuming probiotic microbes did not significantly alter the pre-existing microbial ecology when measured using Illumina sequencing of stool (Poutahidis et al., 2013a). Instead, consumption of L. reuteri did up-regulate levels of anti-inflammatory serum protein IL-10 and concomitantly down-regulate levels of pro-inflammatory IL-17A associated with pathogenic microbial infections (Poutahidis et al., 2013a; Levkovich et al., 2013), when compared with matched animals eating a control diet alone. In this context, probiotic microbe-induced IL-10 served to facilitate immune tolerance and fortify mucocutaneous thickness and repair capability in epithelial barriers (Figure 3), making the host animal more resilient to environmental challenges.

Figure 3. Probiotic-induced ‘glow of health’ depends on anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-10.

Consumption of Lactobacillus reuteri led to upregulated levels of IL-10. Immune-regulatory activities of IL-10 are concentrated along host environmental barriers, such as gastrointestinal and reproductive tract mucosae, and the skin. In addition anti- inflammatory IL-10 has also been implicated in regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal hormones, impacting diverse aspects of host attitude and behaviour. Treg = peripheral T regulatory lymphocytes; APC = antigen-presenting cells.

3. Beneficial microbes bestow ‘glow’ via systemic hormone and immune balance

A ‘glow of health’ has long been considered by medicine traditions as a clinical sign of good health and wellness. In mammals, health and fitness involves tightly integrated hormonal and immune feedback loops that permit microbial commensalism and extended placental pregnancy pivotal in mammalian survival (Lee and Mazmanian, 2010; Samstein et al., 2012; Williams, 2012; Zheng et al., 2010). Immune-regulatory activities of IL-10 are concentrated along external environment barrier surfaces such as gastrointestinal and reproductive tract mucosae, and the skin. In addition to immune tolerance, anti-inflammatory IL-10 has also been implicated either directly or indirectly in regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hormones, impacting diverse aspects of physiology, attitude, and behavior (Roque et al., 2009; Smith et al., 1999).

A well-established paradigm of mucosal homeostasis describes that IL-10 serves to down-regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-17 (Maynard et al., 2012), characteristic of host response to microbe challenges. It was found in recent mouse studies that lowering systemic IL-17 levels reproduced many of the beneficial skin effects of eating probiotic organisms including significantly increased dermal thickness, increased hair follicles in subcutis, hair follicle anagen phase predominance, and an increased sebocyte proliferation index (Levkovich et al., 2013). Likewise, neutralization of circulating IL-17 also served to increase reproductive potential in the form of testicular volume and spermatogenesis in male mice (Poutahidis et al., 2014). Whether in the context of microbial commensalism or mammalian reproduction, hormones such as gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH), estrogen, and testosterone are inextricably linked with epithelial and immune cell functions (Somerset et al., 2004; Williams, 2012). During mammalian reproduction, IL-10 secreted from epithelial cells and antigen presenting cells (APC) facilitates immune tolerance to foreign material through induction of peripheral regulatory T (Treg) lymphocytes (Figure 2) (Samstein et al., 2012; Williams, 2012).

Data from many different animal model systems show that probiotic organisms act to prevent diseases and bestow health via IL-10-mediated induction of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg lymphocytes that serve to down-regulate IL-17 and minimize collateral tissue injury at environmental interfaces (Lee and Mazmanian, 2010; Powrie and Maloy, 2003; Sakaguchi et al., 2010; Di Giacinto et al., 2005; Ilan et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Winer et al., 2009; Poutahidis et al., 2013a). Increased percentages of Foxp3+ protein-bearing CD4+ lymphocytes have been observed in slender, sleek mice after consuming probiotic bacteria (Poutahidis et al., 2013a), coinciding with different inflammatory cell components viewed during microscopic cell count comparisons within skin (Figure 4). Amazingly, purified CD4+ green fluorescent protein (gfp)-Foxp3+ cells from cell donors exposed to L. reuteri are sufficient to convey probiotic-induced skin thickness and hair growth attributes to recipient mice otherwise lacking lymphocytes, even when recipients were not themselves consuming L. reuteri (Poutahidis et al., 2013b). These findings conceptually unify skin health with protection from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and some types of cancer (Rao et al., 2007; Chow and Mazmanian, 2009; Erdman et al., 2009; Lee and Mazmanian, 2010; Poutahidis et al., 2007; Powrie and Maloy, 2003; Round and Mazmanian, 2010). Thus, while many different hormonal and innate immune factors contribute to skin health, adaptive immune CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells emerge as key in conveying resilient skin and mucosae to mammalian hosts.

Figure 4. “Glow of health” phenotype is imparted by probiotic microbe-primed regulatory T lymphocytes.

A) Rag2-deficient mice, which entirely lack functional T- and B-lymphocytes of their own, display the skin histological features of the “glow of health” phenomenon after adoptive cell transfer of purified CD4+ CD25+ Gfp-Foxp3+ regulatory T lymphocytes (Treg). Subsequent Foxp3-specific immunohistochemistry shows that transferred Treg populate the skin of host mice and topographically associate with hair follicles. The transferred Treg originating from L. reuteri ATCC-PTA-6475-exposed donors populate the skin of host mice in significantly (p<0.003) higher numbers compared to when Treg are taken from untreated donor controls. Recipient host mice receiving probiotic-induced Treg show phenotypic features including B) increased subcuticular folliculogenesis and increased skin thickness with C) a hair follicle anagenic shift. By contrast, recipients of Treg taken from untreated control mice do not show these integumentary differences. Numbers on the y-axis of bar graphs represent the mean±SEM of skin thickness in image pixels (B) and hair-follicles classified in each hair cycle stage (C).

(A) Circular image: DAB chromogen, Hematoxylin counterstain. Original magnification ×60. (B) Hematoxylin and Eosin. Bars= 250 mm

4. Host hormone oxytocin unifies microbes and their mammalian hosts in fitness and reproductive success

During earlier studies of ‘glow of health’ in mice, increased social grooming behaviors were observed after consuming purified L. reuteri (Levkovich et al., 2013). In many species, social grooming is regulated by the neuropeptide hormone oxytocin featured in reproduction and infant-mother bonding (Lim and Young, 2006). Neurohypophyseal hormones such as oxytocin and prolactin have a profound impact on mammalian reproductive success; indeed, oxytocin has been inversely linked with post-partum depression and maternal neglect in human females (Skrundz et al., 2011). As a result, microbial alterations in host oxytocin levels may have profound consequences on host health from conception through old age.

Subsequent testing of hormone levels in female C57BL/6 wt mice revealed significant elevations in plasma oxytocin only in those animals drinking probiotics daily, when compared with matched untreated controls (Poutahidis et al., 2013b). Mechanistically, anti-inflammatory IL-10 has also been implicated either directly or indirectly in regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary (HPA) hormones (Roque et al., 2009; Smith et al., 1999). Oxytocin and other HPA hormones may mediate these microbe-triggered attitudes and social behaviors, at least in part due to signaling through the vagus nerve (Bravo et al., 2011; Poutahidis et al., 2013b). In turn, oxytocin interfaces with host immunity via CD25 expression and up-regulation of IFN-gamma in thymic and peripheral lymphocytes (Gimpl and Fahrenholz, 2001; Johnson and Torres, 1985; Maccio et al., 2010; Ndiaye et al., 2008). In this way, microbes apparently interact directly and indirectly with neuroendocrine pathways (Bravo et al., 2011; Foster and McVey Neufeld, 2013; Nicholson et al., 2012) and immune pathways (Chow and Mazmanian, 2009; Chung et al., 2012; Hooper et al., 2012; Maynard et al., 2012) to modify stress-related responses in the skin via a gut-brain-skin axis (Arck et al.).

5. Neuropeptide hormone oxytocin enhances skin wound healing capability

In addition to enhanced grooming and radiant skin, the neurohypophyseal hormone oxytocin has also previously been implicated in the wound healing process (Detillion et al., 2004) in the context of beneficial social bonds and host immune functions (Barnard et al., 2008). Indeed, capability to repair wounded skin is inextricably linked with every aspect of fitness, ranging from daily minor injuries to healthful longevity. Using standard wound healing assays, it was discovered that enriching the gut microbiome with probiotic microbes was sufficient to accelerate the wound-healing process to occur in half the time required for matched control animals in an oxytocin-dependent fashion (Poutahidis et al., 2013b). Wound repair capacity was previously correlated with anagen phase folliculogenesis (Ansell et al., 2011), linking the ‘glow’ phenotype with rapid repair after epithelial injury. Integumentary features characteristic of ‘glow’ including dermal thickening, folliculogenesis, and sebocytogenesis emerged in an oxytocin-dependent manner (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Ability of probiotic microbe-primed regulatory T cells to bestow “glow of health” is enhanced by neuropeptide hormone oxytocin. L. reuteri-primed regulatory T-cells induce rapid hair re-growth in recipient mice.

An alternative adoptive cell transfer paradigm utilizes A) mice of the 129S6/SvEv strain using classical regulatory T-cell isolation methodology. Similar to what has been observed in C57BL/6 strain mice, the B) hair-re-growth phenomenon is replicated in syngeneic host recipient mice. However, ability of probiotic microbe-primed regulatory T cells to bestow “glow of health” requires neuropeptide hormone oxytocin. Regulatory T-lymphocytes from oxytocin-potent, but not from oxytocin-deficient, donor mice are able to induce C) increased hair follicle cycling and D) hair follicle anagenesis and thicker skin in recipient host mice.

(C) Hematoxylin and Eosin. Bars= 250 mm . Numbers on the y-axis of bar graph represent the mean±SEM of skin thickness in image pixels.

It was earlier shown that oxytocin serves to up-regulate CD25 expression in thymic and peripheral lymphocytes (Gimpl and Fahrenholz, 2001; Johnson and Torres, 1985; Maccio et al., 2010; Ndiaye et al., 2008), essentially unifying oxytocin with immune proficiency in the L. reuteri-enriched wound repair effect (Costa et al., 2011). During natural history, oxytocin upon birth simultaneously up-regulates IFN-gamma and CD25 expression culminating in robust yet tightly regulated host immunity without immune anergy enabling establishment of commensal microbiota (Johnson and Torres, 1985; Maccio et al., 2010; Ndiaye et al., 2008). These early life oxytocin-mediated events establish a lifelong framework for constructive host self-versus-nonself interactions, that are subsequently recapitulated later throughout life. In this context, microbe-induced oxytocin emerges as pivotal in a gut microbe-brain-immune axis contributing to good health. In a global sense, an oxytocin connection with ‘glow of health’ is further supported by long-standing medical traditions associating frequent social bonds and favorable feelings of self-worth with efficient recovery after injury, ultimately extending to healthful longevity.

6. Systemic microbial benefits are transplantable to new hosts using immune cells alone

A key role for oxytocin in good systemic health, supported by longstanding medical and social practices, is explainable in part by stimulating CD25 expression in thymic and peripheral immune cells (Gimpl and Fahrenholz, 2001; Johnson and Torres, 1985; Maccio et al., 2010; Ndiaye et al., 2008; Belkaid et al., 2010; Erdman et al., 2010; Erdman et al., 2003; Maloy et al., 2003; Powrie and Maloy, 2003). At the same time, regulatory T (Treg) lymphocytes bearing CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ are widely recognized as a basic cellular carrier of gut microbe-induced signals that shape the immune system to maintain homeostasis throughout the body compatible with good health (Rao et al., 2007; Chow and Mazmanian, 2009; Erdman et al., 2009; Lee and Mazmanian, 2010; Oliveira-Pelegrin et al., 2013; Poutahidis et al., 2007; Powrie and Maloy, 2003; Round and Mazmanian, 2010; Williams, 2012). Interestingly, it was recently shown the probiotic benefit of oxytocin including rapid fur re-growth, dermal thickening, folliculogenesis, and sebocytogenesis was transferable to new animal hosts by transfer of CD4+CD25+ Treg lymphocytes alone (Figure 5), as long as those cells were collected from oxytocin-potent donor animals (Poutahidis et al., 2013b). Thus, oxytocin-competent lymphocytes alone were sufficient to convey gut probiotic microbe-induced signals to inhibit inflammatory-associated pathologies in skin as previously shown in other tissues (Rao et al., 2007; Chow and Mazmanian, 2009; Erdman et al., 2009; Lee and Mazmanian, 2010; Oliveira-Pelegrin et al., 2013; Poutahidis et al., 2007; Powrie and Maloy, 2003; Round and Mazmanian, 2010; Williams, 2012).

7. Gender biases emerge as microbes impart a display of reproductive fitness

In addition to glowing skin, hair density has also been associated with peak health and vitality in humans in many cultures (Muscarella and Cunningham, 1996; Wheeler, 1985). An interesting aspect of robust hair growth was recently revealed in aged male mice drinking L. reuteri daily in water (Levkovich et al., 2013). The hirsute outcome was due to a microbe-induced follicular shift toward a robust 70% of follicles in anagen phase (Levkovich et al., 2013). In aging humans, quiescent telogen phase scalp hairs predominate causing thinning hair with increasing age (Barth, 2000). Increased hair growth and sebocyte formation observed in these mice were shown to be strongly regulated by hormones in other systems (Fimmel et al., 2007; Schneiders and Pausb, 2010); in particular, the androgenic hormone testosterone. Elevated levels of serum testosterone found in male mice after feeding probiotic microbes (Poutahidis et al., 2014) may serve to stimulate sebocytes and associated hair follicles (Liva and Voskuhl, 2001; Schneiders and Pausb, 2010). Male pattern baldness in humans is incompletely understood, but is attributed to complex interactions between genetics, hormones, and inflammation (Rebora, 2004). It’s tempting to extrapolate to humans from these data of mice. However, interpretation is complicated by disparities in hair on scalp versus other body sites of these two species (Wheeler, 1985). It is unknown whether eating of probiotic microbes may forestall follicular activities of hormones and inflammation in aging human subjects.

Although the skin of both genders of mice improved significantly after eating dietary probiotics, the female animals, in particular, showed more robust alterations in skin pH and fur luster (Figure 1). The mechanisms underlying gender-related differences in the skin physiology remain elusive, although they likely reflect the differential effects of sex steroid hormones and associated immunology of skin and mucosal surfaces found in each gender (Dao and Kazin, 2007). It was observed separately that female mice consuming L. reuteri have higher serum estradiol levels than untreated control mice with duller fur (data not shown). In women, acidic vaginal pH correlated with Lactobacillus sp abundance, estrogen level, and peak fertility (Ravel et al., 2011). This suggested that probiotic bacteria induce host physiological changes including a more acidic pH that contributes to radiant skin and shiny hair signaling peak health and fertility to conspecifics. It follows logically that the luminous display of superb health is inherently attractive to other members of the same species.

8. The gut-brain-immune-skin axis is more than skin deep

These observations led us to propose mechanistic models where both probiotic organisms and the resident GI microbiome (Mozaffarian et al.; Turnbaugh et al., 2006) affect host hypophyseal–pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis hormones and immunity (Poutahidis et al., 2013a; Poutahidis et al., 2013b; Poutahidis et al., 2014) in systemic health (Figure 6 and 7). Systemic effects of inflammatory cells and cytokines (Chinen and Rudensky, 2012; Hooper et al., 2012; Lee and Mazmanian, 2010; Maynard et al., 2012; Tlaskalova-Hogenova et al., 2011), have been shown to have important roles in skin health and disease (Cavani et al., 2012; Hacini-Rachinel et al., 2009), and in hair follicle cycling (Stenn and Paus, 2001). Immune tolerance in the form of IL-10 and regulatory lymphocytes shapes host health by inhibiting pro-inflammatory skin pathologies, a fitness mechanism more broadly associated with microbial commensals and placental pregnancy (Rao et al., 2007; Chow and Mazmanian, 2009; Erdman et al., 2009; Lee and Mazmanian, 2010; Oliveira-Pelegrin et al., 2013; Poutahidis et al., 2007; Powrie and Maloy, 2003; Round and Mazmanian, 2010; Williams, 2012) that is more than skin deep.

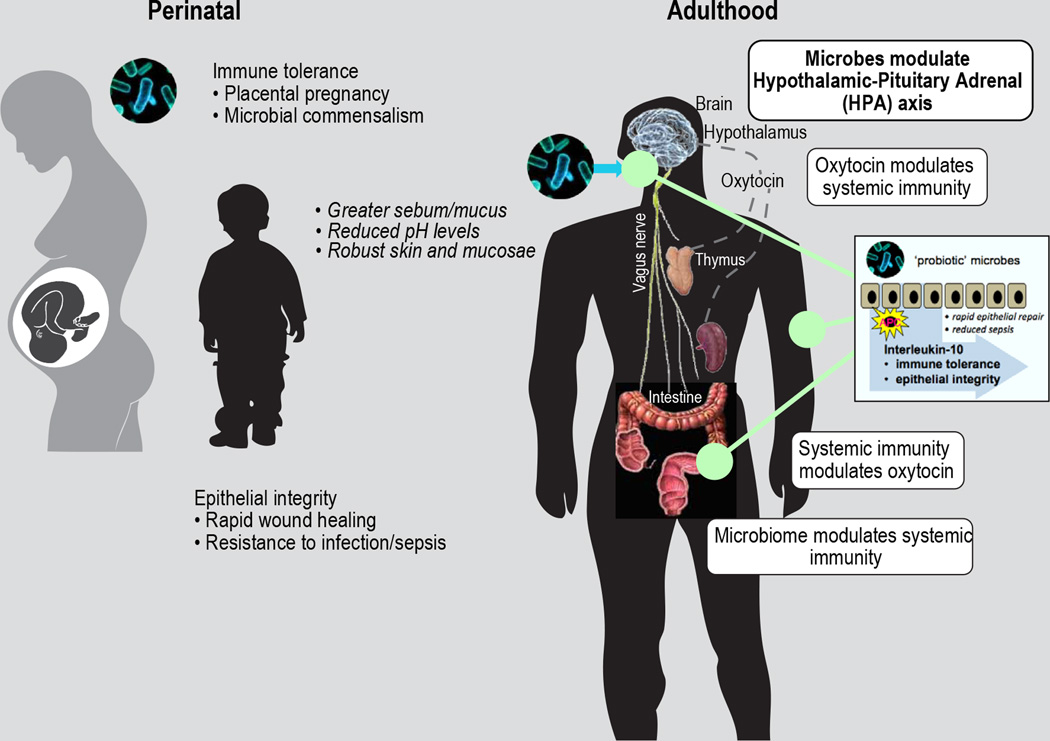

Figure 6. The gut-brain-immune-skin axis.

Imbalanced interactions of commensal bacteria within the gut may lead to a chronic systemic, often subclinical, pro-inflammatory millieu that predisposes to an array of adverse effects that feedback into a destructive inflammation-driven cycle. Dietary probiotic bacteria simultaneously stimulate the hypothalamus and pituitary gland to secrete health stimulating hormones, while also stimulating the regulatory arm of the immune system. Together, these two probiotic microbe-induced events, though not yet fully understood, interact to break the vicious pro-inflammatory cycle and boost good health-associated phenotypes in tissues distant from the GI tract, such as the skin.

Figure 7. Perinatal probiotic microbe host benefits extrapolate to good health in adulthood.

Mammalian good health and fitness involves hormonal and immune feedback loops tightly integrated with physiology that universally eables microbial commensalism and extended placental pregnancy. Upon birth, oxytocin simultaneously up-regulates IFN-gamma and CD25 expression in thymus and the periphery culminating in robust yet tightly regulated host immunity involving immune-regulatory activities of IL-10 concentrated along the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and reproductive tract mucosae, and in the skin. These early life oxytocin-mediated events establish a lifelong framework for constructive host self-versus-nonself interactions, that are subsequently recapitulated later throughout life. probiotic microbe-induced phenotypes not only imbue good health to the host, but are also inherently attractive to others as they overtly signal host leadership and reproductive potential.

From an evolutionary perspective, probiotic commensal bacteria co-evolved with mammals exploiting endogenous hormonal and immune pathways to optimize host physical, mental and social fitness for mutual benefit. Survival advantages linked with oxytocin may extend beyond maternal-infant bonding to social superiority by enhancing cooperation within social groups while promoting aggression towards competitors (De Dreu et al., 2010). These inter-related roles for microbes, IL-10, and oxytocin may impact a natural selection process favoring complex social organizations required for mutual evolutionary success.

9. Conclusions

Dietary probiotic bacteria simultaneously stimulate the anti-inflammatory regulatory arm of the immune system and the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to secrete cytokines and hormones that interrupt a destructive chronic pro-inflammatory cycle, culminating in superb host physique and reproductive health. In practical terms, probiotic-induced phenotypes not only imbue good health to the host, but are also inherently charismatic and attractive to others as they overtly signal leadership and reproductive potential. Under favorable conditions, the probiotic bacteria also benefit, as they are then passed from mother to offspring during birth and nursing, imparting evolutionary success to both species. Humans have cultivated and consumed similar food-grade probiotic organisms in fermented beverages and active yogurts for thousands of years, supporting a low-risk, high-impact population-based microbe-endocrine-immune approach for overall good health.

Acknowledgements

We thank James Versalovic for the gift of ATCC 6475 Lactobacillus reuteri, and special thanks to James G. Fox for encouragement and support.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P30-ES002109 (pilot project award to S.E.E), RO1CA108854 (to S.E.E), and U01 CA164337 (to S.E.E.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Ansell DM, Kloepper JE, Thomason HA, Paus R, Hardman MJ. Exploring the “hair growth-wound healing connection”: anagen phase promotes wound re-epithelialization. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:518–528. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arck P, Handjiski B, Hagen E, Pincus M, Bruenahl C, Bienenstock J, Paus R. Is there a 'gut-brain-skin axis'? Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:401–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard A, Layton D, Hince M, Sakkal S, Bernard C, Chidgey A, Boyd R. Impact of the neuroendocrine system on thymus and bone marrow function. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2008;15:7–18. doi: 10.1159/000135619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth JH. Should men still go bald gracefully? Lancet. 2000;355:161–162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y, Liesenfeld O, Maizels RM. 99th Dahlem conference on infection, inflammation and chronic inflammatory disorders: induction and control of regulatory T cells in the gastrointestinal tract: consequences for local and peripheral immune responses. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:35–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG, Bienenstock J, Cryan JF. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16050–16055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavani A, Pennino D, Eyerich K. Th17 and Th22 in skin allergy. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2012;96:39–44. doi: 10.1159/000331870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapat L, Chemin K, Dubois B, Bourdet-Sicard R, Kaiserlian D. Lactobacillus casei reduces CD8+ T cell-mediated skin inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2520–2528. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinen T, Rudensky AY. The effects of commensal microbiota on immune cell subsets and inflammatory responses. Immunol Rev. 2012;245:45–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow J, Mazmanian SK. Getting the bugs out of the immune system: do bacterial microbiota “fix” intestinal T cell responses? Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Pamp SJ, Hill JA, Surana NK, Edelman SM, Troy EB, Reading NC, Villablanca EJ, Wang S, Mora JR, Umesaki Y, Mathis D, Benoist C, Relman DA, Kasper DL. Gut immune maturation depends on colonization with a host-specific microbiota. Cell. 2012;149:1578–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell. 2012;148:1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa RA, Ruiz-de-Souza V, Azevedo GM, Jr, Gava E, Kitten GT, Vaz NM, Carvalho CR. Indirect effects of oral tolerance improve wound healing in skin. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19:487–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dao H, Jr, Kazin RA. Gender differences in skin: a review of the literature. Gend Med. 2007;4:308–328. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu CK, Greer LL, Handgraaf MJ, Shalvi S, Van Kleef GA, Baas M, Ten Velden FS, Van Dijk E, Feith SW. The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans. Science. 2010;328:1408–1411. doi: 10.1126/science.1189047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detillion CE, Craft TK, Glasper ER, Prendergast BJ, DeVries AC. Social facilitation of wound healing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giacinto C, Marinaro M, Sanchez M, Strober W, Boirivant M. Probiotics ameliorate recurrent Th1-mediated murine colitis by inducing IL-10 and IL-10-dependent TGF-beta-bearing regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:3237–3246. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SE, Rao VP, Olipitz W, Taylor CL, Jackson EA, Levkovich T, Lee CW, Horwitz BH, Fox JG, Ge Z, Poutahidis T. Unifying roles for regulatory T cells and inflammation in cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1651–1665. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SE, Rao VP, Poutahidis T, Ihrig MM, Ge Z, Feng Y, Tomczak M, Rogers AB, Horwitz BH, Fox JG. CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory lymphocytes require interleukin 10 to interrupt colon carcinogenesis in mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6042–6050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SE, Rao VP, Poutahidis T, Rogers AB, Taylor CL, Jackson EA, Ge Z, Lee CW, Schauer DB, Wogan GN, Tannenbaum SR, Fox JG. Nitric oxide and TNF-{alpha} trigger colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis in Helicobacter hepaticus-infected, Rag2-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812347106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fimmel S, Saborowski A, Terouanne B, Sultan C, Zouboulis CC. Inhibition of the androgen receptor by antisense oligonucleotides regulates the biological activity of androgens in SZ95 sebocytes. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39:149–156. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-961815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floch MH, Walker WA, Madsen K, Sanders ME, Macfarlane GT, Flint HJ, Dieleman LA, Ringel Y, Guandalini S, Kelly CP, Brandt LJ. Recommendations for probiotic use-2011 update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;(45 Suppl):S168–S171. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318230928b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JA, McVey Neufeld KA. Gut-brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura KE, Slusher NA, Cabana MD, Lynch SV. Role of the gut microbiota in defining human health. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8:435–454. doi: 10.1586/eri.10.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal A, Tamir S, Tannenbaum SR, Wogan GN. Nitric oxide production in SJL mice bearing the RcsX lymphoma: a model for in vivo toxicological evaluation of NO. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11499–11503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimpl G, Fahrenholz F. The oxytocin receptor system: structure, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:629–683. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JI. Honor thy gut symbionts redux. Science. 2012;336:1251–1253. doi: 10.1126/science.1224686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueniche A, Bastien P, Ovigne JM, Kermici M, Courchay G, Chevalier V, Breton L, Castiel-Higounenc I. Bifidobacterium longum lysate, a new ingredient for reactive skin. Exp Dermatol. 2010;16:511–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueniche A, Benyacoub J, Buetler TM, Smola H, Blum S. Supplementation with oral probiotic bacteria maintains cutaneous immune homeostasis after UV exposure. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:511–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacini-Rachinel F, Gheit H, Le Luduec JB, Dif F, Nancey S, Kaiserlian D. Oral probiotic control skin inflammation by acting on both effector and regulatory T cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336:1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilan Y, Maron R, Tukpah AM, Maioli TU, Murugaiyan G, Yang K, Wu HY, Weiner HL. Induction of regulatory T cells decreases adipose inflammation and alleviates insulin resistance in ob/ob mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9765–9770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908771107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HM, Torres BA. Regulation of lymphokine production by arginine vasopressin and oxytocin: modulation of lymphocyte function by neurohypophyseal hormones. J Immunol. 1985;135:773s–775s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutmann J. Pre- and probiotics for human skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;54:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YK, Mazmanian SK. Has the microbiota played a critical role in the evolution of the adaptive immune system? Science. 2010;330:1768–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1195568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkovich T, Poutahidis T, Smillie C, Varian BJ, Ibrahim YM, Lakritz JR, Alm EJ, Erdman SE. Probiotic bacteria induce a 'glow of health'. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MM, Young LJ. Neuropeptidergic regulation of affiliative behavior and social bonding in animals. Horm Behav. 2006;50:506–517. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litonjua AA, Weiss ST. Is vitamin D deficiency to blame for the asthma epidemic? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1031–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liva SM, Voskuhl RR. Testosterone acts directly on CD4+ T lymphocytes to increase IL-10 production. J Immunol. 2001;167:2060–2067. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccio A, Madeddu C, Chessa P, Panzone F, Lissoni P, Mantovani G. Oxytocin both increases proliferative response of peripheral blood lymphomonocytes to phytohemagglutinin and reverses immunosuppressive estrogen activity. In Vivo. 2010;24:157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloy KJ, Salaun L, Cahill R, Dougan G, Saunders NJ, Powrie F. CD4+CD25+ T(R) cells suppress innate immune pathology through cytokine-dependent mechanisms. J Exp Med. 2003;197:111–119. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune system. Nature. 2012;489:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nature11551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty NP, Yatsunenko T, Hsiao A, Faith JJ, Muegge BD, Goodman AL, Henrissat B, Oozeer R, Cools-Portier S, Gobert G, Chervaux C, Knights D, Lozupone CA, Knight R, Duncan AE, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Newgard CB, Heath AC, Gordon JI. The impact of a consortium of fermented milk strains on the gut microbiome of gnotobiotic mice and monozygotic twins. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:106ra106. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2392–2404. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Rover S, Handjiski B, van der Veen C, Eichmuller S, Foitzik K, McKay IA, Stenn KS, Paus R. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscarella F, Cunningham MR. “The evolutionary significance and social perception of male pattern baldness and facial hair”. Ethology and Sociobiology. 1996;17:99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Ndiaye K, Poole DH, Pate JL. Expression and regulation of functional oxytocin receptors in bovine T lymphocytes. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:786–793. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.065938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neish AS. Microbes in gastrointestinal health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:65–80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, Burcelin R, Gibson G, Jia W, Pettersson S. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336:1262–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noverr MC, Huffnagle GB. Does the microbiota regulate immune responses outside the gut? Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Pelegrin GR, Saia RS, Carnio EC, Rocha MJ. Oxytocin affects nitric oxide and cytokine production by sepsis-sensitized macrophages. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2013;20:65–71. doi: 10.1159/000345044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plikus MV, Chuong CM. Complex hair cycle domain patterns and regenerative hair waves in living rodents. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1071–1080. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutahidis T, Haigis KM, Rao VP, Nambiar PR, Taylor CL, Ge Z, Watanabe K, Davidson A, Horwitz BH, Fox JG, Erdman SE. Rapid reversal of interleukin-6-dependent epithelial invasion in a mouse model of microbially induced colon carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2614–2623. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutahidis T, Kearney SM, Levkovich T, Qi P, Varian BJ, Lakritz JR, Ibrahim YM, Chatzigiagkos A, Alm EJ, Erdman SE. Microbial Symbionts Accelerate Wound Healing via the Neuropeptide Hormone Oxytocin. PLoS One. 2013a;8:e78898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutahidis T, Kleinewietfeld M, Smillie C, Levkovich T, Perrotta A, Bhela S, Varian BJ, Ibrahim YM, Lakritz JR, Kearney SM, Chatzigiagkos A, Hafler DA, Alm EJ, Erdman SE. Microbial Reprogramming Inhibits Western Diet-Associated Obesity. PLoS One. 2013b;8:e68596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutahidis T, Springer A, Levkovich T, Qi P, Varian BJ, Lakritz JR, Ibrahim YM, Chatzigiagkos A, Alm EJ, Erdman SE. Probiotic microbes sustain youthful serum testosterone levels and testicular size in aging mice. PLoS One In Press. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powrie F, Maloy KJ. Immunology. Regulating the regulators. Science. 2003;299:1030–1031. doi: 10.1126/science.1082031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VP, Poutahidis T, Fox JG, Erdman SE. Breast cancer: should gastrointestinal bacteria be on our radar screen? Cancer Res. 2007;67:847–850. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, Karlebach S, Gorle R, Russell J, Tacket CO, Brotman RM, Davis CC, Ault K, Peralta L, Forney LJ. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4680–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebora A. Pathogenesis of androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:777–779. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roque S, Correia-Neves M, Mesquita AR, Almeida Palha J, Sousa N. Interleukin-10: A Key Cytokine in Depression? Cardiovascular Psychiatry and Neurology. 2009;2009:187894. doi: 10.1155/2009/187894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Round JL, Mazmanian SK. Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12204–12209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909122107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, Miyara M, Costantino CM, Hafler DA. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:490–500. doi: 10.1038/nri2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samstein RM, Josefowicz SZ, Arvey A, Treuting PM, Rudensky AY. Extrathymic generation of regulatory T cells in placental mammals mitigates maternal-fetal conflict. Cell. 2012;2012:1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MR, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Paus R. The hair follicle as a dynamic miniorgan. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R132–R142. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiders M, Pausb R. Sebocytes, multifaceted epithelial cells: Lipid production and holocrine secretion. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2010;42:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan F. The gut microbiota-a clinical perspective on lessons learned. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:609–614. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrundz M, Bolten M, Nast I, Hellhammer DH, Meinlschmidt G. Plasma oxytocin concentration during pregnancy is associated with development of postpartum depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1886–1893. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EM, Cadet P, Stefano GB, Opp MR, Hughes TK. IL-10 as a mediator in the HPA axis and brain. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 1999;100:140–148. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerset DA, Zheng Y, Kilby MD, Sansom DM, Drayson MT. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the immune suppressive CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T-cell subset. Immunology. 2004;112:38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenn KS, Paus R. Controls of hair follicle cycling. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:449–494. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg JP, Peters EM, Paus R. Analysis of hair follicles in mutant laboratory mice. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:264–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, Stepankova R, Kozakova H, Hudcovic T, Vannucci L, Tuckova L, Rossmann P, Hrncir T, Kverka M, Zakostelska Z, Klimesova K, Pribylova J, Bartova J, Sanchez D, Fundova P, Borovska D, Srutkova D, Zidek Z, Schwarzer M, Drastich P, Funda DP. The role of gut microbiota (commensal bacteria) and the mucosal barrier in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases and cancer: contribution of germ-free and gnotobiotic animal models of human diseases. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8:110–120. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li J, Tang L, Charnigo R, de Villiers W, Eckhardt E. T-lymphocyte responses to intestinally absorbed antigens can contribute to adipose tissue inflammation and glucose intolerance during high fat feeding. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler PE. “The loss of functional body hair in man: the influence of thermal environment, body form and bipedality”. Journal of Human Evolution. 1985;14:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Williams Z. Inducing tolerance to pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1159–1161. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1207279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer S, Chan Y, Paltser G, Truong D, Tsui H, Bahrami J, Dorfman R, Wang Y, Zielenski J, Mastronardi F, Maezawa Y, Drucker DJ, Engleman E, Winer D, Dosch HM. Normalization of obesity-associated insulin resistance through immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2009;15:921–929. doi: 10.1038/nm.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young VB. The intestinal microbiota in health and disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28:63–69. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32834d61e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Josefowicz SZ, Chaundhry A, Peng XP, Forbush K, Rudensky AY. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature. 2010;463:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature08750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]