Abstract

Objectives

Chloride intracellular channel protein 4 (Clic4) is a ubiquitously expressed protein involved in multiple cellular processes including cell-cycle control, cell differentiation, and apoptosis. Here, we investigated the role of Clic4 in pancreatic β-cell apoptosis.

Methods

We used βTC-tet cells and islets from β-cell specific Clic4 knockout mice (βClic4KO) and assessed cytokine-induced apoptosis, Bcl2 family protein expression and stability, and identified Clic4-interacting proteins by co-immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry analysis.

Results

We show that cytokines increased Clic4 expression in βTC-tet cells and in mouse islets and siRNA-mediated silencing of Clic4 expression in βTC-tet cells or its genetic inactivation in islets β-cells, reduced cytokine-induced apoptosis. This was associated with increased expression of Bcl-2 and increased expression and phosphorylation of Bad. Measurement of Bcl-2 and Bad half-lives in βTC-tet cells showed that Clic4 silencing increased the stability of these proteins. In primary islets β-cells, absence of Clic4 expression increased Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression as well as expression and phosphorylation of Bad. Mass-spectrometry analysis of proteins co-immunoprecipitated with Clic4 from βTC-tet cells showed no association of Clic4 with Bcl-2 family proteins. However, Clic4 co-purified with proteins from the proteasome suggesting a possible role for Clic4 in regulating protein degradation.

Conclusions

Collectively, our data show that Clic4 is a cytokine-induced gene that sensitizes β-cells to apoptosis by reducing the steady state levels of Bcl-2, Bad and phosphorylated Bad.

Keywords: Clic4, β-cells, Apoptosis, Cytokines, Bcl-2, Diabetes

1. Introduction

A complete destruction of pancreatic β-cells, caused by an autoimmune reaction, underlies the development of type 1 diabetes [1]. In type 2 diabetes, a partial reduction in β-cell mass is also observed and may contribute to the impaired capacity of the endocrine pancreas to secrete enough insulin to compensate for the development of insulin resistance in peripheral tissues [2]. The destruction of β-cells in Type 1 diabetes is mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IFN-γ and TNF-α [1,3], and by other pro-apoptotic mediators provided by activated immune cells, such as FasL and perforins/granzymes [4,5]. In type 2 diabetes, pancreatic islets also show signs of inflammation with infiltrating macrophages [6] and increased production of cytokines and chemokines by the islet cells themselves [7,8]. Evidence for toxic effects of elevated glucose and saturated free fatty acid levels (glucolipotoxicity) on β-cells is well established [9–13], and energy-dense diets, rich in refined sugars and saturated fats can contribute to loss of functional β-cells through apoptosis. Cytokines (IL-1β, IFN-γ and TNF-α) induce apoptosis following binding to their specific receptors and activation of NF-κB, STAT1 and JNK [14–16], leading to activation of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins [17]. These proteins interact with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins through their Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3) domain in a hierarchical way [18]. The balance and interaction between these proteins decides cell fate by activating or inactivating pro-death proteins Bax and Bak [19,20], which then triggers apoptosis following mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) [21]. Saturated free fatty acids are thought to induce apoptosis in large part through an initial activation of the ER stress pathway [10] that leads to activation of protein kinase R-like ER kinase (PERK), inositol requiring 1 (IRE1) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6). However, this ultimately also converges on the activation of the pro-apoptotic Bcl2 family proteins that activate mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and caspase 3-dependent apoptosis [22,23].

Because both forms of diabetes are associated with apoptosis-dependent loss of β-cell mass, identifying novel proteins involved in the control of apoptosis may lead to novel approaches to preserve β-cell mass and the insulin secretion capacity of the endocrine pancreas.

Clic4 (chloride intracellular channel 4) is a 28 kDa protein, which was initially cloned from rat brain [24] and proposed to be a chloride channel because of its homology to p64, a member of the chloride ion channel family [24,25]; this proposed channel function, however, has not been supported by more recent studies [26]. In contrast, Clic4 has been implicated in regulating cell cycle arrest, cell differentiation, and apoptosis, [27–31]. In keratinocytes, Clic4 is up-regulated by TNF-α [32] and in p53- or c-myc-mediated apoptosis [33,34]. Clic4 is found in the cytosol but under some conditions it may be associated with mitochondria or the nucleus and increase apoptosis through cytochrome c release from mitochondria and caspase-3 activation [32,35].

Here, we investigated the role of Clic4 in pancreatic β-cell apoptosis by suppressing Clic4 expression in βTC-tet cells or by using islets from β-cell specific conditional Clic4 knockout mice (βClic4KO). We showed that siRNA-mediated Clic4 silencing in βTC-tet cells or its genetic inactivation in islets β-cells reduces the sensitivity of these cells to cytokines- or palmitic acid-induced apoptosis. Moreover, we show that Clic4 knockdown reduces the degradation rate of Bcl-2 and Bad and increases the total level of phosphorylated Bad, possibly as a result of Clic4 interaction with the proteasome.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

TNF-α and IL-1β were purchased from Calbiochem (Nyon, Switzerland); IFN-γ, palmitic acid, cycloheximide from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); exendin-4 from Bachem AG (Bubendorf, Switzerland); protease and phosphatase inhibitors were from Roche (Rotkreuz, Switzerland); other reagents were of analytical or cell culture grade purity.

2.2. Antibodies

Rabbit anti-actin and mouse anti-α-tubulin were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); rabbit antibodies to caspase-3, Bcl2, Bcl-xL, Bad, phospho-Bad (ser-112) and Bax were from Cell signaling (Danvers, MA, USA); rabbit antibodies to phospho-Bim (ser-69), Bim, Puma, phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr-183/Tyr-185), SAPK/JNK were from Cell signaling. Secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (from donkey) and HRP conjugated anti-mouse IgG (from sheep) were from GE healthcare (Nyon, Switzerland).

2.3. Cell culture

The mouse pancreatic βTC-tet cell line [36] were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium + glutamax (Gibco, Zug, Switzerland), supplemented with 15% horse serum, 2.5% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator and used between passages 20 and 35.

Min6(B1) cells [37] were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium + glutamax, supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 71 μM β-mercaptoethanol and used between passages 19 and 30.

2.4. Clic4 specific siRNA and reverse transfection

The Clic4 specific siRNA (siClic4) has the following sequence: CCG CAA CTT TGA TAT TCC TAA AGG A (Invitrogen, Zug, Switzerland). Cells were reverse transfected by diluting 150 nM of siClic4 or siCT (negative control siRNA, Invitrogen, Zug, Switzerland) in serum free medium in a tissue culture plate; 7.5 μl of Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen, Zug, Switzerland) was then added and incubated at room temperature for 20 min to form Lipid-siRNA complex. The complex was diluted to five times with growth medium containing 1 × 106 βTC-tet cells to obtain a final siRNA concentration of 30 nM. The transfected cells were incubated at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator (medium was replaced after every 24 h) and were used for the experiments, 48 h after transfection.

2.5. Generation of β-cell specific Clic4 conditional knockout mice

Clic4 floxed mice were generated by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells using the strategy depicted in Figure 5A (Genoway, Lyon, France). The neo cassette was removed by crossing Clic4lox/+ mice with Flp-deleter mice. The neomycin negative male Clic4lox/+ mice were then crossed with female Ins1Cre/+ mice [38] to generate Clic4lox/+; Ins1Cre/+ and Clic4lox/+ mice. Mice with homozygous β-cell deletion of Clic4 were generated by crossing Clic4lox/+; Ins1Cre/+ mice with Clic4lox/+ mice in order to obtain Clic4lox/lox; Ins1 Cre/+ mice (βClic4KO) and control littermates (Control). Mice were on a C57BL/6 background. All studies were performed with littermates. Mice were housed on a 12-h light/dark cycle and fed a standard rodent chow (Diet 3436; Provimi Kliba AG, Penthallaz, Switzerland).

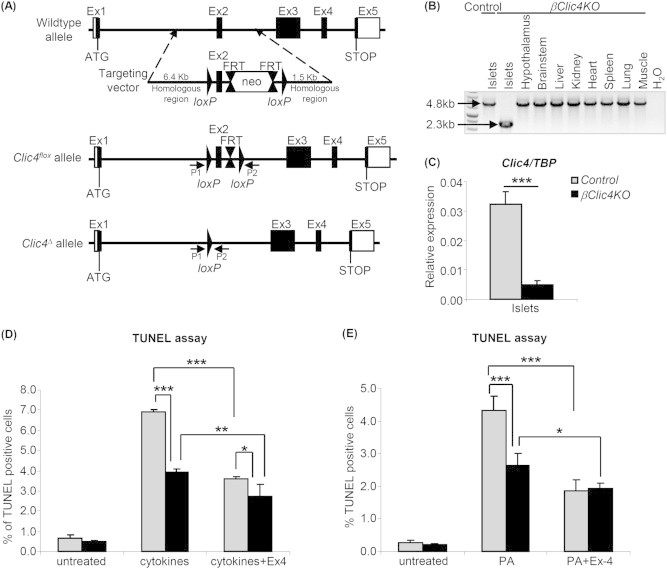

Figure 5.

Generation of βClic4KO mice and resistance to apoptosis of βClic4KO β-cells. (A) Top: structure of the wild type Clic4 allele and of the targeting vector; middle: structure of the Clic4flox allele; bottom: structure of the Clic4Δ allele after InsCre-mediated recombination. (B) PCR analysis of Clic4 recombination using the P1 and P2 primers (see A). (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Clic4 expression in islets from βClic4KO or control mice. (D, E) Islets from Control or βClic4KO mice were plated on extracellular matrix-coated dishes for 6 days to form monolayers. (D) Cells were then left untreated or pre-incubated with 100 nM exendin-4 (Ex4) for 9 h and then treated with cytokines for 15 h. (E) Cells were left untreated or treated with 1 mM palmitic acid (PA) with or without 100 nM exendin-4 (Ex-4) for 48 h. In (D) and (E), apoptosis was measured by TUNEL assay and is expressed as percentage of TUNEL-positive cells over total DAPI positive cells. The data are the means ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

2.6. Islets isolation and culture

Islets were isolated from 8 to 12-week-old mice as described in Ref. [39] and, after handpicking, they were kept overnight in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Zug, Switzerland), supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM Glutamax, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Islets were then kept in suspension for western blot analysis or for apoptosis and proliferation experiments. For other experiments (see Section 2.7), 20 islets were plated on tissue culture dishes coated with an extracellular matrix (ECM) derived from bovine corneal endothelial cells (Novamed, Jerusalem, Israel) for 6–7 days to form monolayers, before starting treatment.

2.7. Cell treatment

For apoptosis measurements, βTC-tet cells or pancreatic islets were treated with cytokines (25 ng/ml TNF-α, 10 ng/ml IL-1β and 10 ng/ml IFN-γ) for 15 h, or treated with 100 nM exendin-4 for 24 h or 48 h, or treated for 48 h with 1 mM palmitic acid (a stock solution containing 10 mM palmitic acid and 20% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) was prepared by dissolving 34.8 mg sodium palmitate in 4 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at ∼70 °C, and adding 2.5 g of fatty acid-free BSA dissolved in 8 ml of PBS, the final volume was brought to 12.5 ml with PBS and stored in aliquots at −20 °C).

2.8. Clic4 antibody generation

Clic4 C-terminal and N-terminal peptides (MALSMPLNGLKEEDKEPC and CKEVEIAYSDVAKRLTK, respectively) were conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin and used to immunize New Zealand White rabbits. Immunization consisted in one boost injection and repeated challenges with 1 mg of peptides. The rabbits were killed after a total of five injections for serum collection and specific antibodies were purified by affinity chromatography. Antibody production was made by Biotem (Grenoble, France).

2.9. Gel electrophoresis and western blot

βTC-tet cells or mouse islets were washed twice with cold PBS and lysed on ice for 20 min in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P40, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were sonicated for 15 s, centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C and supernatants were collected. The protein concentrations were determined by BCA assay (Thermo scientific, Erembodegem, Belgium) and equal amounts of protein lysates were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies and revealed using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Advansta, CA, USA); quantification of the band density was performed by densitometric analysis.

2.10. Apoptosis assay

Apoptotic cells were identified by TUNEL assay using In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Cell nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The signals were visualized with a fluorescence microscope Leica (Nidau, Switzerland). Photomicrographs were captured under green (TUNEL positive) and blue (DAPI positive) channels at 20× magnification and merged using the Leica software. Each condition reported represents >2500 cells (βTC-tet cells or islet cells) counted by randomized field selection. The apoptosis is reported as the percent of TUNEL positive nuclei over the total number of nuclei stained by DAPI, as quantitated by Image J software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

2.11. Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from islets and βTC-tet cells using RNeasy Plus micro kit (Qiagen, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland) and RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland), respectively, and cDNAs were synthesized using SuperScript® II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Zug, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Expression of target genes was measured by real time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) using 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Zug, Switzerland) in a final volume of 10 μl containing 2 μl of cDNA and 5 μl of power SYBR Green PCR mix (Applied Biosystems; Zug, Switzerland), in the presence of forward and reverse primers. Expression values were normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene TATA-box binding protein (TBP). Primer sequences are: for Bcl-2 (F) 5′-GATGACTGAGTACCTGAACCG-3′, (R) 5′-CAGAGACAGCCAGGAGAAATC-3′; for Bcl-xL (F) 5′-GGAAAGCGTAGACAAGGAGATG-3′, (R) 5′-GCATTGTTCCCGTAGAGATCC-3′; for Bad (F) 5′-AGGATGAGCGATGAGTTTGAG-3′, (R) 5′-CCTTTGCCCAAGTTTCGATC-3′; for Clic4 (F) 5′-GACAAAGAGCCCCTCATCGA-3′, (R) 5′-GTTTCCAATGCTTTCACCATC-3′; TBP (F) 5′-ATCCCAAGCGATTTGCTGC-3′, (R) 5′-ACTCTTGGCTCCTGTGCACA-3′. All the primers were obtained from Microsynth (Balgach, Switzerland).

2.12. Immunoprecipitation and LC–MS/MS analysis

βTC-tet cells were lysed in the immunoprecipitation buffer (20 mM Tris, pH-7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40 containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors). One mg of cell lysate proteins was incubated overnight with 7 μg of anti-Clic4 C-terminus, anti-Clic4 N-terminus, or rabbit IgGs at 4 °C with gentle rocking. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C the supernatants were collected and added on Protein G-Agarose beads (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with gentle rocking and washed four times with the immunoprecipitation buffer. After washing, beads were heated in sample buffer (75 mM Tris, pH-6.8, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 2.5% SDS) for 5 min at 95 °C and used for western blotting or mass-spectrometric (MS) analysis.

For mass-spectrometric analysis, immunoprecipitates were fractionated by electrophoresis on a polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie blue. Gel lanes were cut into six equal regions from top to bottom. They were then reduced by dithiothreitol, alkylated with iodoacetamide and digested with trypsin (Promega, Madison, USA) as described in Ref. [40,41]. Liquid chromatography–MS/MS analysis of the extracted peptide mixtures was carried out on a hybrid linear trap LTQ-Orbitrap XL (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) mass spectrometer interfaced to a nanocapillary HPLC equipped with a C18 reversed-phase column (Thermo Scientific). Collection of tandem mass spectra for database searching were generated from raw data with Mascot Distiller and searched using Mascot 2.4.1 (Matrix Science, London, UK) against the release 2012_11 of the SwissProt database (www.uniprot.org) restricted to Mus musculus taxonomy. Mascot was searched with a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.50 Da and a parent ion tolerance of 10 ppm, allowing two missed cleavages. Iodoacetamide derivative of cysteine was specified as a fixed modification. Protein N-term acetylation, deamidation of asparagine and glutamine, and oxidation of methionine were specified as variable modifications. The software Scaffold (version Scaffold_4.1.1, Proteome Software Inc.) was used to validate MS/MS based peptide (minimum 90% probability [42], with delta-mass correction) and protein (min. 95% probability [43]) identifications. Dataset alignment as well as parsimony analysis to discriminate homologous hits was carried out by Scaffold. Proteins sharing significant peptide evidence were grouped into clusters.

2.13. Glucose stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS)

βTC-tet cells or Min6(B1) were transfected with siCT or siClic4. 72 h later, they were washed with PBS and pre-incubated for 2 h in KRBH-BSA (Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate HEPES buffer containing 120 mM NaCl, 4 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM NaHCO3, and 0.5% BSA, pH7.4) supplemented with 2 mM glucose, later the medium was replaced with fresh KRBH-BSA containing 2 or 20 mM glucose and incubated for 1 h in the presence or absence of 100 nM Exendin-4. Secreted and cellular insulin were assessed by radioimmunoassay (RIA) using RIA kit (Millipore, MA, USA) following manufacturer's instructions.

2.14. Study approval

All breeding and cohort maintenance were performed in the UNIL animal facility, and all the experiments were approved by the Service Vétérinaire du Canton de Vaud, Switzerland.

2.15. Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. Comparisons were performed using unpaired Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance for the different groups followed by posthoc pairwise multiple-comparison procedures with the Tukey test. Single, double, and triple asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

3. Results

3.1. Clic4 expression is induced by cytokines and its silencing protects against apoptosis

We first investigated whether Clic4 protein expression in βTC-tet cells and primary mouse islets was increased by cytokines treatment. Figure 1A,B, shows that a 15 h treatment with Il-1β, TNFα and IFNγ increased Clic4 protein expression by ∼30% in βTC-tet cells and by ∼100% in primary mouse islets (Figure 1C,D).

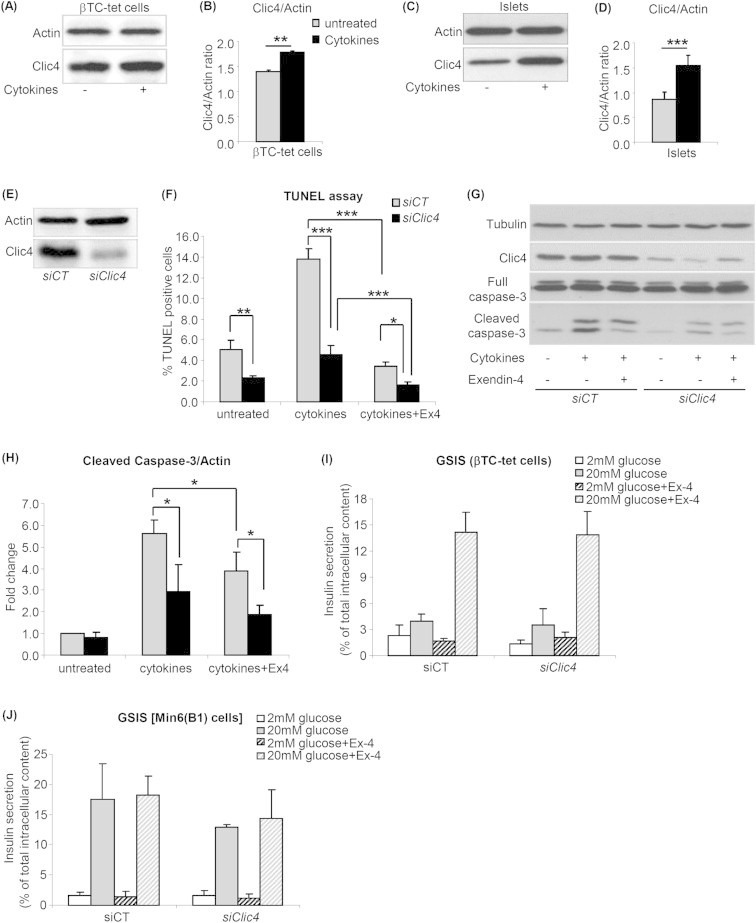

Figure 1.

Clic4 is a cytokine-induced protein and its silencing protects against cytokine-induced apoptosis. βTC-tet cells (A,B) or primary mouse islets (C,D) were left untreated or treated with cytokines (IL-1β, IFN-γ, TNF-α) for 15 h and Clic4 expression was measured by western blot analysis (A,C) and quantitated by densitometry analysis (B,D). Data are mean ± SD, n = 3 independent experiments. (E–H) βTC-tet cells were transfected with siCT or siClic4. 48 h later they were exposed to 100 nM exendin-4 (Ex4) or left untreated for 9 h and then treated with cytokines for 15 h. The efficacy of Clic4 silencing was tested by western blot analysis (E). Apoptosis was measured by TUNEL assay (F) or by western blot analysis of cleaved caspase-3; (G) western blot, (H) quantitation by densitometry analysis. The data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. βTC-tet cells (I) or Min6(B1) cells (J) were transfected with siCT or siClic4. 72 h later, they were exposed to either 2 or 20 mM glucose for 1 h in the presence or absence of 100 nM exendin-4 (Ex-4). Insulin secretion is expressed as percent of total intracellular content. The data are the means ± SD from three independent experiments.

To assess the effect of Clic4 silencing on cytokines-induced apoptosis, we transfected βTC-tet cells with a control or a Clic4-specific siRNA and assessed cytokine-induced apoptosis, in the presence or absence of 100 nM exendin-4 added 9 h prior to the addition of cytokines. Figure 1F shows an ∼3-fold increase in apoptosis upon cytokine treatment in siCT-transfected cells and a complete protection against apoptosis by exendin-4. Upon Clic4 silencing, the basal rate of apoptosis was reduced by 50% as compared to siCT-transfected cells and cytokines increased apoptosis by 2-fold, to a level that was still ∼3-fold lower than in siCT-transfected cells; exendin-4 still significantly reduced cytokine-induced apoptosis. The extent of siRNA-mediated Clic4 silencing is shown by western blot analysis in Figure 1E.

We also assessed apoptosis by measuring caspase-3 cleavage by western blot analysis. Figure 1G,H shows that cytokine-induced caspase-3 cleavage was reduced by ∼50% in the siClic4-transfected cells as compared with siCT-transfected cells and this cleavage was still significantly reduced by exendin-4.

Collectively, these data showed that Clic4 expression is induced by cytokines and sensitizes βTC-tet cells to cytokine-induced apoptosis. In addition, the anti-apoptotic effect of GLP-1 is still present upon Clic4 silencing indicating that GLP-1 signaling is independent of Clic4 expression.

To determine whether Clic4 is required for the normal control of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, we silenced Clic4 in βTC-tet cells and in Min6B1 cells and exposed the cells to 2 or 20 mM glucose and in the presence and absence of exendin-4. As shown in Figure 1I,J Clic4 silencing did not impact glucose stimulated insulin secretion.

3.2. Clic4 silencing increases Bcl-2 and Bad expression as well as Bad phosphorylation

Cytokines induce β-cell apoptosis mainly through activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, which involves the participation of anti- and pro-apoptotic Bcl2-family proteins [17]. We thus examined whether Clic4 silencing would modulate expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Bad. Here, siCT- or siClic4-transfected βTC-tet cells were treated or not with cytokines for 15 h. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed no difference in Bcl2, Bad and Bcl-xL mRNA expression in siCT or siClic4 transfected cells and no change in response to cytokine treatment (data not shown). However, western blot analysis of whole cell lysates showed that silencing Clic4 increased expression of Bcl-2 (∼2-fold), Bad (∼1.4 fold), of phosphorylated Bad (pBad) (∼2 fold), and of the pBad/Bad ratio (Figure 2B–E). Clic4 silencing did not affect Bcl-xL protein expression under basal conditions or after cytokine treatment (Figure 2F) and only slightly decreased Bax protein expression after cytokine treatment (Figure 2G).

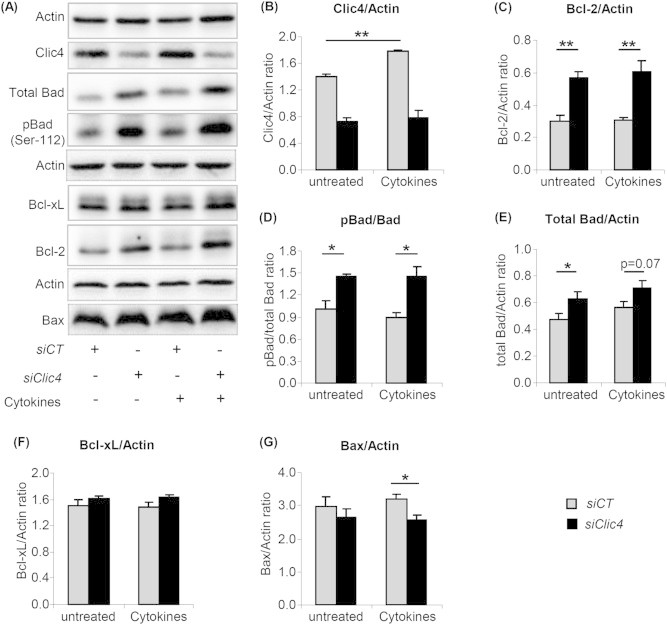

Figure 2.

Clic4 silencing increases Bcl-2 and Bad expression as well as Bad phosphorylation. (A) Western blot analysis of the indicated proteins and of the phosphorylated form of Bad in βTC-tet cells transfected with siCT or siClic4 and treated 48 h later with or without cytokines for an additional 15 h period. Densitometry analysis of the proteins normalized to β-actin is shown in (B–G) as is the ratio of phosphorylated Bad (pBad) to total Bad (D). The data are the means ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

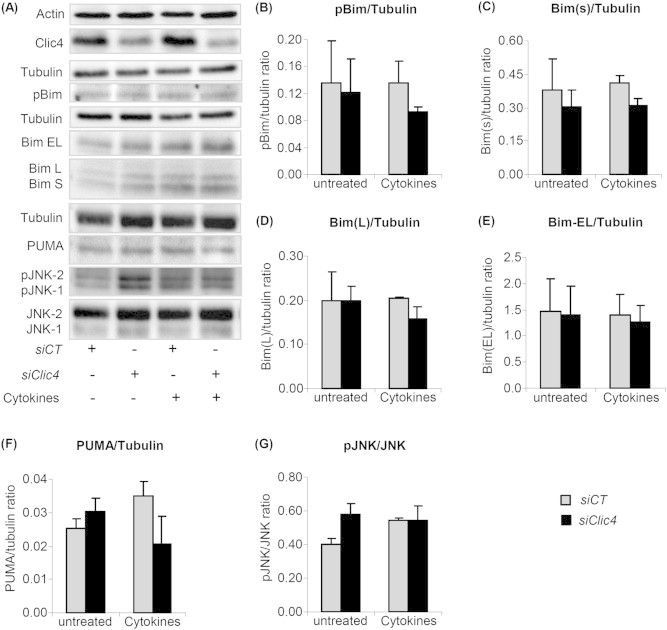

3.3. Clic4 silencing did not affect expression of PUMA, Bims, BimL, BimxL and phosphorylation of Bim and JNK in βTC-tet cells

We next examined expression of the pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, PUMA and Bim. It has been shown that JNK-induced Bim phosphorylation on serine 65 contributes to β-cell apoptosis [44]. Moreover Bim has three main isoforms generated by alternative splicing, namely BimEL, BimL and the most pro-apoptotic variant Bims [45]. Hence we examined protein expression of all three variants of Bim, phosphorylated Bim, JNK activation and PUMA in siCT- or siClic4-transfected βTC-tet cells treated or not with cytokines for 15 h. The western blot of Figure 3A-G, shows that Clic4 silencing did not affect the expression level of PUMA, the three variants of Bim, or the phosphorylation state of JNK or Bim.

Figure 3.

Clic4 silencing did not affect expression of PUMA, Bims, BimL, BimEL or the phosphorylation of Bim and JNK. (A) βTC-tet cells were transfected with siCT or siClic4. After 48 h, cells were left untreated or treated with cytokines for 15 h and expression of the indicated proteins was evaluated by western blot analysis. Densitometry analysis of protein expression normalized to β-actin is shown in (B–G). The data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Thus, Clic4 silencing reduces cytokines-induced apoptosis was correlated with increased expression of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bad, and increased phosphorylation of Bad (Figure 2).

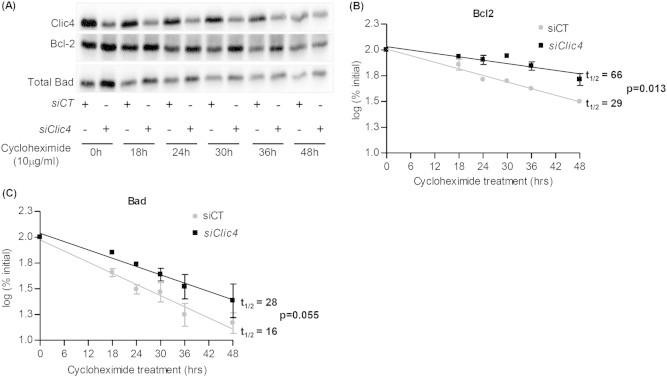

3.4. Clic4 knockdown increases the half-life of Bcl-2 and Bad

To determine whether Clic4 silencing could increase Bcl-2 and Bad stability, siCT- or siClic4-transfected βTC-tet cells were treated with cycloheximide for different periods of time and the level of expression of both proteins was assessed by western blot analysis. The rate of protein degradation was expressed as log of the percentage of initial value at t = 0 and protein half-life (t1/2) was measured by regression analysis. Clic4 silencing increased Blc2 and Bad half-lives (Figure 4A–C) from ∼29 h to ∼66 h for Bcl2, and from ∼16 h to ∼28 h for Bad.

Figure 4.

Clic4 silencing increases the half-lives of Bcl-2 and Bad. (A) βTC-tet cells were transfected with siCT or siClic4. 48 h later they were left untreated or were treated with cycloheximide for the indicated periods of time, and Bcl-2 and Bad expression was quantitated by western blot analysis. (B, C) Densitometry analysis of the Bcl2 (B) and Bad (C) expression data were plotted on a logarithmic scale. The protein half-lives (t1/2) were calculated by regression analysis (inset). The data are means ± SD from three independent experiments.

3.5. Generation of β-cell specific Clic4 conditional knockout (βClic4KO) mice

To study the role of Clic4 in primary β-cells, we generated mice with β-cell-specific inactivation of Clic4. Figure 5A shows the recombination strategy in which exon 2 of the Clic4 gene was flanked by loxP sites by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Clic4lox/lox mice were crossed with Ins1Cre mice [38], which ensure complete and β-cell-selective floxed gene recombination, in order to obtain Clic4 lox/lox;Ins1Cre/+ (βClic4KO) and Clic4 lox/lox;Ins1+/+ (Control) mice. Selective recombination in the islets was confirmed by PCR analysis of recombined alleles (Figure 5B); this led to ∼85% reduction in Clic4 gene expression in βClic4KO mouse islets (Figure 5C), consistent with Clic4 inactivation in all β-cells.

To assess whether inactivation of Clic4 in β-cells would impact glucose homeostasis, we generated cohorts of male and female control and βClic4KO mice and fed them a normal chow for 18 weeks, or a high fat diet for 12 weeks starting at 6 weeks of age. No difference in glucose tolerance nor in insulin secretion could be observed between Control and βClic4KO mice following intraperitoneal glucose injections, nor any difference in β-cell mass (not shown).

3.6. Islet β-cells from βClic4KO mice are less sensitive to induced apoptosis

Islets from control and βClic4KO mice were cultured on extracellular-coated Petri dishes to induce monolayer formation. Cells were then exposed to cytokines for 15 h with or without a 9 h pretreatment with exendin-4. Apoptosis was then measured by TUNEL assay. Figure 5D shows that cytokines induced apoptosis in ∼7% of control islet cells and ∼4% of βClic4KO islets. Exendin-4 significantly reduced cytokine-induced apoptosis in both types of islets. Similarly, palmitic acid-induced apoptosis was lower in βClic4KO β-cells and exendin-4 also reduced apoptosis in both types of islets (Figure 5E). Thus, Clic4 is also a pro-apoptotic protein in primary islet cells. Note that we did not specifically measure apoptosis in β-cells but rather in the whole islet cell population, but the use of Ins1Cre mice ensures that Clic4 is inactivated only in β-cells [38].

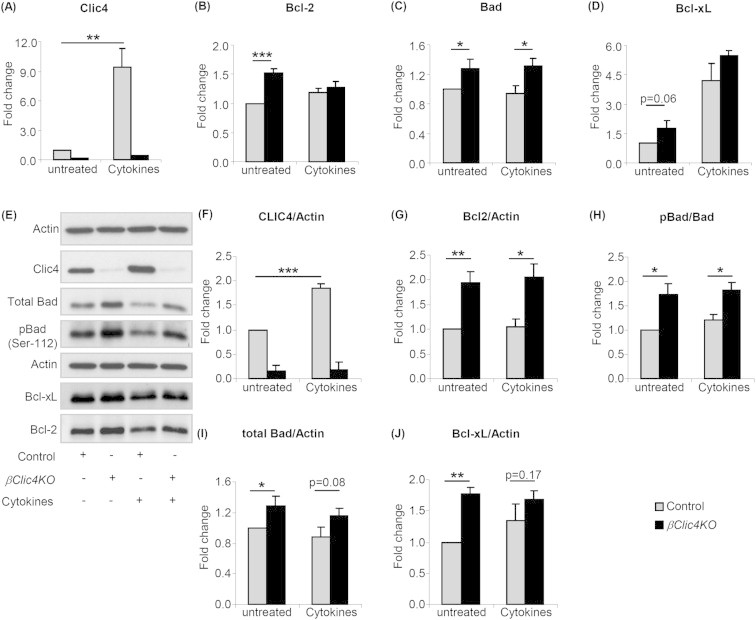

3.7. Islets from βClic4KO mice have increased expression of Bcl2, Bcl-xL, Bad, and pBad

We next evaluated Bcl-2, Bad and Bcl-xL mRNA expression in islets from βClic4KO and control mice exposed or not to cytokines for 15 h. Figure 6A shows that Clic4 mRNA expression was increased by ∼9-fold after cytokine treatment in control islets; Bcl-2 mRNA expression was increased by 50% in islets from βClic4KO mice in the absence of treatment but was not different after cytokine treatment (Figure 6B); Bad mRNA expression was increased by ∼30% in islets from βClic4KO mice under basal conditions and following cytokines treatment (Figure 6C) and Bcl-xL mRNA level was not significantly different in islets from βClic4KO or control mice under basal conditions or following cytokine treatment (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Increased expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bad and pBad in islets from βClic4KO mice. (A–D) Islets from βClic4KO or control mice were left untreated or treated with cytokines for 15 h and expression levels of Clic4, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Bad mRNAs were assessed by qRT-PCR; expression levels were normalized to tbp mRNA levels and expressed relative to the levels found in non-treated control islets. (E) Western blot analysis of the indicated proteins in the islets of control and βClic4KO mice treated or not with cytokines. (F–J) Densitometry analysis of the proteins normalized to β-actin and of the ratio of pBad/Bad. The data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Western blot analysis of islets from control and βClic4KO mice, treated or not with cytokines for 15 h, showed an ∼2-fold increased expression of Bcl-2 in the islets from βClic4KO mice as compared to control islets, both in the presence or absence of cytokines. Total Bad expression and the level of phosphorylated Bad were also increased in βClic4KO mouse islets and the ratio of pBad to total Bad was increased by ∼75% in basal conditions and ∼60% after cytokines treatment (Figure 6H). Bcl-xL expression was higher by ∼77% in islets from βClic4KO mice as compared with islet from control mice; this difference no longer reached significance after cytokine treatment (Figure 6J).

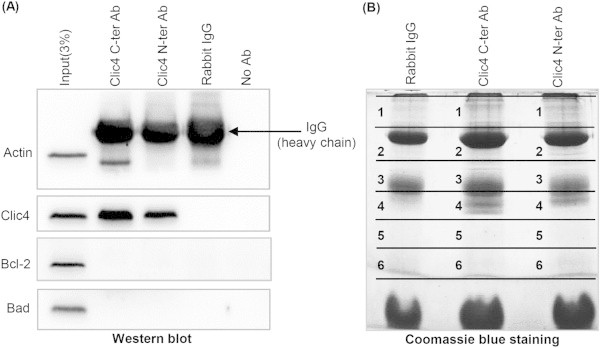

3.8. Mass-spectrometry analysis of proteins associated with Clic4

Because the above data indicated higher level and stability of Bcl2, Bad and pBad in the absence of Clic4, we wondered whether this could be due to the suppression of a direct interaction of Clic4 with these proteins. We therefore immunoprecipitated Clic4 from βTC-tet cells using antibodies directed against the C- or N-terminal ends of the protein and subjected the immunoprecipitates to western blot and LC–MS/MS analysis. Figure 7A shows that Clic4 antibodies efficiently immunoprecipitated Clic4 and that neither Bcl2 nor Bad co-immunoprecipitated with Clic4. The co-immunoprecipitates were then separated by gel electrophoresis (Figure 7B) and the individual lanes were cut in small segments for trypsin digestion and mass spectrometry analysis. We identified 78 proteins that were selectively enriched in the Clic4 co-immunoprecipitates as compared with the control IgG co-immunoprecipitate. Sixty-six proteins were co-immunoprecipitated with the C-terminal antibody, 10 with the N-terminal antibody, and two with both antibodies (Table 1). The proteins were grouped according to their biological or cellular functions (Table 1), showing that they pertain to diverse cellular processes such as proteasomal degradation, protein biosynthesis, cell cycle, kinase/phosphatases, apoptosis, protein transport and regulator of GTPase activity.

Figure 7.

Mass-spectrometry analysis of proteins associated with Clic4. (A) Clic4 was immunoprecipitated from 1 mg of βTC-tet cell lysate proteins using the C- or N-terminal Clic4 antibodies; rabbit IgGs were used as a negative immunoprecipitation control. The immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by western blotting for co-immunoprecipitation with Bcl2 and Bad, which was negative. (B) The immunoprecipipates of (A) were also subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining. Each gel lanes was cut into six regions, digested with trypsin and analyzed by mass spectrometry analysis for analysis of proteins specifically associated with Clic4 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

List of Clic4-binding proteins identified by mass-spectrometry. Proteins co-immunoprecipitated with Clic4 from βTC-tet cells (Figure 7) were identified by mass spectrometry. Most of the proteins were pulled-down with the C-terminal antibody. *Indicates the proteins pulled-down with the N-terminal antibody and ** indicates those pulled-down with both C- and N-terminal antibodies.

| List of Clic4-binding proteins | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins involved in protein biosynthesis | Proteins involved in cell cycle | ||

| 1 | Ile-tRNA synthetase | 46 | DNA replication licensing factor MCM2 |

| 2 | Arg-tRNA synthetase | 47 | Replication factor C subunit 5 |

| 3 | Met-tRNA synthetase | 48 | Chromosome transmission fidelity protein 18 homolog |

| 4 | Leu-tRNA synthetase | 49 | Paired amphipathic helix protein Sin3a |

| 5 | Asp-tRNA synthetase | 50 | CD2-associated protein |

| 6 | Lys-tRNA synthetase | 51 | Sister chromatid cohesion protein DCC1 |

| 7 | Ala-tRNA synthetase | 52* | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| 8 | Thr-tRNA synthetase | 53 | Centrosomal protein of 89 kDa |

| 9 | Glu-Pro-tRNA synthetase | 54 | Kinetochore-associated protein NSL1 homolog |

| 10 | AIMP1/p43 | 55 | Kinetochore-associated protein DSN1 homolog |

| 11 | AIMP2/p38 | 56 | Polyamine-modulated factor 1 |

| 12 | AIMP3/p18 | 57 | Protein CASC5 |

| 13–17 | eIF3 subunit B, A, H, M, E | 58* | NIF3-like protein 1 |

| 18** | 40S ribosomal protein S9 | 59* | Cyclin-G-associated kinase |

| 19** | 60S ribosomal protein L17 | Kinases/Phosphatases | |

| Proteins involved in apoptosis | 60-61 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase type I-alpha and type II-alpha. | |

| 10 | AIMP1/p43 | 62* | Serine/threonine-protein kinase MRCK beta |

| 11 | AIMP2/p38 | 63* | Protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 12A |

| 12 | AIMP3/p18 | 64* | Myotubularin-related protein 5 |

| Proteins involved in protein degradation | 65* | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-beta catalytic subunit | |

| 20–26 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 2, 1, 11, 13, 6, 7, 5. | 66 | Type II inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 5-phosphatase |

| 27–31 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 8, 6B, 7, 10B, 4. | Proteins involved in GTPase activity | |

| 32 | F-box only protein 28 | 67 | Arf-GAP |

| 33 | DNA damage-binding protein 1 | 68 | RhoGEF (Factor 12 and 1) |

| Proteins transport | 69 | Dedicator of cytokinesis protein 7 | |

| 34 | Kinesin-1 heavy chain | 70 | SH3 domain-binding protein 1 |

| 35–37 | Kinesin light chain 1, 2 and 4 | 71* | Neurofibromin |

| 38 | Kinesin-like protein KIF11 | 72* | BTB/POZ domain-containing protein KCTD12 |

| 39 | 14-3-3 protein epsilon | 73* | GTPase-activating protein and VPS9 domain-containing protein 1 |

| 40 | Torsin-1A-interacting protein 1 | 74* | Jouberin |

| 41 | AP-3 complex subunit beta-1 | Others | |

| 42* | Membrane-associated phosphatidylinositol transfer protein 1 | 43* | SUN domain-containing protein 2 |

| 75 | Spectrin beta chain | 76 | Spectrin alpha chain |

| 44 | Myomegalin | 77 | F-actin-capping protein subunit beta |

| Proteins involved in cell cycle | 78* | 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | |

| 45 | DNA replication licensing factor MCM3 | ||

Unmarked, protein pull-down with C-ter Ab; *, protein pull-down with N-ter Ab; **, protein pull down by both C- and N-ter Ab.

4. Discussion

The present study shows that Clic4 is a cytokine-induced gene in pancreatic β-cells, and that silencing its expression in βTC-tet cells or inactivating its gene in primary β-cells markedly reduces cytokines-induced apoptosis. β-cells from βClic4KO mice were also more resistant to lipotoxicity, suggesting a role for Clic4 also in ER-stress mediated apoptosis. Suppressing Clic4 expression leads to increased stability of Bcl-2 and Bad and increased levels of pBad. Liquid chromatography–MS/MS analysis revealed that Clic4 does not directly interact with Bcl2 family proteins, while it interacts with components of the proteasome and other protein classes. Thus, Clic4 is a newly described β-cell pro-apoptotic gene that regulates the half-lives of Bcl-2 family proteins through an indirect mechanism, possibly involving proteasome action.

Cytokines induce β-cell apoptosis mainly through activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, which involves regulated expression of anti- and pro-apoptotic Bcl2-family proteins and their differential interactions eventually leading to induction of mitochondrial permeability, cytochrome c release, and activation of caspase 3 [17]. Here, we showed that Clic4 knockdown in βTC-tet cells or genetic inactivation in islets β-cells increased expression of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and led to increased phosphorylation of Bad, which inhibits its pro-apoptotic activity. Increased expression of these proteins was independent from changes in their mRNA levels, indicating a regulation at the translational or posttranslational level. Analysis of protein stability showed that the half-lives of Bcl-2 and Bad were indeed markedly prolonged in the absence of Clic4. Mass spectrometry analysis of the Clic4-interacting proteins did not reveal any interactions with Bcl2 family proteins suggesting that Clic4 has an indirect role on Bcl2 and Bad stability. This analysis, however, revealed interactions of Clic4 with several proteins involved in proteosomal degradation, suggesting that Clic4 may regulate the rate of Bcl2 family proteins degradation through proteasomal activity. We attempted to determine whether blocking proteasomal activity with a specific inhibitor, MG132, would impact the stability of Bcl2 or Bad in the presence or absence of Clic4. However, MG132 treatment was toxic for βTC-tet cells leading to their death already 12 h after beginning of the treatment. This prevented analysis of the impact of blocking proteasome activity on Bcl-2 and Bad because their half-lives are greater than 20 h. Whether absence of Clic4 has a role in the control of Bad and Bcl2 biosynthesis is not yet known.

Clic4 also sensitizes β-cells to palmitic-acid induced apoptosis, a process associated with increased expression of ER stress markers [46,47]. In βTC-tet cells, thapsigargin-induced ER stress increased the expression of the ER stress markers genes Chop, Atf4, Gadd34, Atf6, Bip, and the spliced form of Xbp1 to the same extent in control or Clic4-silenced cells (data not shown). Thus, the protection against lipotoxicity conferred by Clic4 silencing is unlikely due to repression of ER stress markers but may depend on the increased stability of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and pBad.

Mass spectrometry analysis of Clic4 immunoprecipitates revealed that Clic4 binds to proteins involved in several cellular process or functions, including protein biosynthesis, cell-cycle, apoptosis, protein degradation, protein transport, and kinases or phosphatases. These data suggest that Clic4 may affect cell survival through different mechanisms, possibly in a context dependent manner.

Finally, CLIC4 is also well expressed in human islets (Median RPKM 23, RNASeq data [48]), and there is a 1.7-fold increase in its expression following a 48 h exposure to cytokines while there is no clear change in expression following 48 h palmitate exposure (Median RPKM 26; n = 5 [49]). CLIC4 is also well expressed in FACS-purified rat beta cells, with a 5–7-fold increase in expression after 6 or 24 h exposure to IL-1 + IFNγ or TNF + IFNγ [50]. It is conceivable that we did not see a more marked increase in CLIC4 expression human islets due to the late time of study.

Collectively, our data show that Clic4 sensitizes β-cells to cytokines- or palmitic acid-induced apoptosis. Reducing Clic4 expression increases β-cell survival, an event associated with, and likely caused by, the increased stability and cellular expression levels of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and of the phosphorylated form of Bad. It is indeed known that Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL overexpression in β-cells increases their resistance to cytokine-induced apoptosis [51–53]. Thus, targeting Clic4 expression or its interaction with specific protein partners identified in our mass spectrometry analysis may provide a new way to prevent β-cell apoptosis in the context of diabetes mellitus.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Manfredo Quadroni and Dr. Patrice Waridel from the protein analysis facility of the Center for Integrative Genomics of the UNIL, for the mass spectrometry analysis.

Footnotes

Grant support: This study was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (3100A0B-128657 to BT), a European Research Council (268946) advanced grant (INSIGHT, to BT), an Innovative Medicine Initiative Joint Undertaking grant No. 155005 (IMIDIA), resources of which are composed of financial contributions from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) and EFPIA companies in kind contribution and the European Union Framework Program 7 Collaborative Project BetaBat to BT and DE.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Eizirik D.L., Colli M.L., Ortis F. The role of inflammation in insulitis and β-cell loss in type 1 diabetes. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2009;5:219–226. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler A.E., Janson J., Bonner-Weir S., Ritzel R., Rizza R.A., Butler P.C. β-cell deficit and increased β-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:102–110. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathis D., Vence L., Benoist C. β-cell death during progression to diabetes. Nature. 2001;414:792–798. doi: 10.1038/414792a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eizirik D.L., Mandrup-Poulsen T. A choice of death–the signal-transduction of immune-mediated b-cell apoptosis. Diabetologia. 2001;44:2115–2133. doi: 10.1007/s001250100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas H.E., McKenzie M.D., Angstetra E., Campbell P.D., Kay T.W. Beta cell apoptosis in diabetes. Apoptosis. 2009;14:1389–1404. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0339-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehses J.A., Perren A., Eppler E., Ribaux P., Pospisilik J.A., Maor-Cahn R. Increased number of islet-associated macrophages in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56(9):2356–2370. doi: 10.2337/db06-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maedler K., Sergeev P., Ris F., Oberholzer J., Joller-Jemelka H.I., Spinas G.A. Glucose-induced beta-cell production of interleukin-1beta contributes to glucotoxicity in human pancreatic islets. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110:851–860. doi: 10.1172/JCI15318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Igoillo-Esteve M., Marselli L., Cunha D.A., Ladrière L., Ortis F., Grieco F.A. Palmitate induces a pro-inflammatory response in human pancreatic islets that mimics CCL2 expression by beta cells in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2010;53(7):1395–1405. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1707-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhodes C.J. Type 2 diabetes-a matter of β-cell life and death? Science. 2005;307:380–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1104345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eizirik D.L., Cardozo A.K., Cnop M. The role for endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetes mellitus. Endocrine Reviews. 2008;29:42–61. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donath M.Y., Gross D.J., Cerasi E., Kaiser N. Hyperglycemia-induced beta-cell apoptosis in pancreatic islets of Psammomys obesus during development of diabetes. Diabetes. 1999;48:738–744. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.4.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gremlich S., Bonny C., Waeber G., Thorens B. Fatty acids decrease IDX-1 expression in rat pancreatic islets and reduce GLUT2, glucokinase, insulin, and somatostatin levels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:30261–30269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donath M.Y., Dalmas É., Sauter N.S., Böni-Schnetzler M. Inflammation in obesity and diabetes: islet dysfunction and therapeutic opportunity. Cell Metabolism. 2013;17(6):860–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardozo A.K., Heimberg H., Heremans Y., Leeman R., Kutlu B., Kruhøffer M. A comprehensive analysis of cytokine induced and nuclear factor-kB-dependent genes in primary rat pancreatic b-cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:48879–48886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore F., Naamane N., Colli M.L., Bouckenooghe T., Ortis F., Gurzov E.N. STAT1 is a master regulator of pancreatic beta cells apoptosis and islet inflammation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:929–941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donath M.Y., Storling J., Maedler K., Mandrup-Poulsen T. Inflammatory mediators and islet beta-cell failure: a link between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Journal of Molecular Medicine (Berlin) 2003;81:455–470. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0450-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurzov E.N., Eizirik D.L. Bcl-2 proteins in diabetes: mitochondrial pathways of β-cell death and dysfunction. Trends in Cell Biology. 2011;21(No. 27) doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H., Rafiuddin-Shah M., Tu H.C., Jeffers J.R., Zambetti G.P., Hsieh J.J. Hierarchical regulation of mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis by BCL-2 subfamilies. Nature Cell Biology. 2006;8:1348–1358. doi: 10.1038/ncb1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross A., Jockel J., Wei M.C., Korsmeyer S.J. Enforced dimerization of BAX results in its translocation, mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. EMBO Journal. 1998;17:3878–3885. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim H., Tu H.C., Ren D., Takeuchi O., Jeffers J.R., Zambetti G.P. Stepwise activation of BAX and BAK by tBID BIM, and PUMA initiates mitochondrial apoptosis. Molecular Cell. 2009;36:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tait S.W., Green D.R. Mitochondria and cell death: outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2010;11:621–632. doi: 10.1038/nrm2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang D., Armstrong J.S. Bax and the mitochondrial permeability transition cooperate in the release of cytochrome c during endoplasmic reticulum-stress-induced apoptosis. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2007;14:703–715. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hacki J., Egger L., Monney L., Conus S., Rosse T., Fellay I. Apoptotic crosstalk between the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria controlled by Bcl-2. Oncogene. 2000;19:2286–2295. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duncan R.R., Westwood P.K., Boyd A., Ashley R.H. Rat brain p64H1, expression of a new member of the p64 chloride channel protein family in endoplasmic reticulum. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:23880–23886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howell S., Duncan R.R., Ashley R.H. Identification and characterization of a homologue of p64 in rat tissues. FEBS Letters. 1996;390:207–210. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00676-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Littler D.R., Harrop S.J., Goodchild S.C., Phang J.M., Mynott A.V., Jiang L. The enigma of the CLIC proteins: ion channels, redox proteins, enzymes, scaffolding proteins? FEBS Letters. 2010;584:2093–2101. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suh K.S., Mutoh M., Gerdes M., Yuspa S.H. CLIC4, an intracellular chloride channel protein, is a novel molecular target for cancer therapy. Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings. 2005;10:105–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.200402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohman S., Matsumoto T., Suh K., Dimberg A., Jakobsson L., Yuspa S. Proteomic analysis of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced endothelial cell differentiation reveals a role for chloride intracellular channel 4 (CLIC4) in tubular morphogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:42397–42404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tung J.J., Hobert O., Berryman M., Kitajewski J. Chloride intracellular channel 4 is involved in endothelial proliferation and morphogenesis in vitro. Angiogenesis. 2009;12:209–220. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9139-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronnov-Jessen L., Villadsen R., Edwards J.C., Petersen O.W. Differential expression of a chloride intracellular channel gene, CLIC4, in transforming growth factor-beta1-mediated conversion of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. American Journal of Pathology. 2002;161:471–480. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64203-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulmasov B., Bruno J., Gordon N., Hartnett M.E., Edwards J.C. Chloride intracellular channel protein-4 functions in angiogenesis by supporting acidification of vacuoles along the intracellular tubulogenic pathway. American Journal of Pathology. 2009;174:1084–1096. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandez-Salas E., Suh K.S., Speransky V.V., Bowers W.L., Levy J.M., Adams T. mtCLIC/CLIC4, an organellular chloride channel protein, is increased by DNA damage and participates in the apoptotic response to p53. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002;22:3610–3620. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3610-3620.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandez-Salas E., Sagar M., Cheng C., Yuspa S.H., Weinberg W.C. p53 and tumor necrosis factor α regulate the expression of a mitochondrial chloride channel protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:36488–36497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiio Y., Suh K.S., Lee H., Yuspa S.H., Eisenman R.N., Aebersold R. Quantitative proteomic analysis of myc-induced apoptosis: a direct role for Myc induction of the mitochondrial chloride ion channel, mtCLIC/CLIC4. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:2750–2756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suh K.S., Mutoh M., Nagashima K., Fernandez-Salas E., Edwards L.E., Hayes D.D. The organellular chloride channel protein CLIC4/mtCLIC translocates to the nucleus in response to cellular stress and accelerates apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:4632–4641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311632200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Efrat S., Fusco-DeMane D., Lemberg H., al Emran O., Wang X. Conditional transformation of a pancreatic beta-cell line derived from transgenic mice expressing a tetracycline-regulated oncogene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1995;92(8):3576–3580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lilla V., Webb G., Rickenbach K., Maturana A., Steiner D.F., Halban P.A. Differential gene expression in well-regulated and dysregulated pancreatic beta-cell (MIN6) sublines. Endocrinology. 2003;144(4):1368–1379. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thorens B., Tarussio D., Maestro M.A., Rovira M., Heikkila E., Ferrer J. Ins1Cre knock-in mice for beta cell-specific gene recombination. Diabetologia. 2014 Dec 11 doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3468-5. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 25500700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cornu M., Modi H., Kawamori D., Kulkarni R.N., Joffraud M., Thorens B. Glucagon-like peptide-1 increases beta-cell glucose competence and proliferation by translational induction of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(14):10538–10545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.091116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shevchenko A., Wilm M., Vorm O., Mann M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Analytical Chemistry. 1996;68(5):850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilm M., Shevchenko A., Houthaeve T., Breit S., Schweigerer L., Fotsis T. Femtomole sequencing of proteins from polyacrylamide gels by nano-electrospray mass spectrometry. Nature. 1996;379(6564):466–469. doi: 10.1038/379466a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keller A., Nesvizhskii A.I., Kolker E., Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Analytical Chemistry. 2002;74(20):5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nesvizhskii A.I., Keller A., Kolker E., Aebersold R. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 2003;75(17):4646–4658. doi: 10.1021/ac0341261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santin I., Moore F., Colli M.L., Gurzov E.N., Marselli L., Marchetti P. PTPN2, a candidate gene for type 1 diabetes, modulates pancreatic b-cell apoptosis via regulation of the BH3-only protein Bim. Diabetes. 2011;60:3279–3288. doi: 10.2337/db11-0758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nogueira T.C., Paula F.M., Villate O., Colli M.L., Moura R.F., Cunha D.A. GLIS3, a susceptibility gene for type 1 and type 2 diabetes, modulates pancreatic beta cell apoptosis via regulation of a splice variant of the BH3-only protein Bim. PLoS Genetics. 2013;9(5):e1003532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kharroubi I., Ladrière L., Cardozo A.K., Dogusan Z., Cnop M., Eizirik D.L. Free fatty acids and cytokines induce pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis by different mechanisms: role of nuclear factor-kappaB and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5087–5096. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karaskov E., Scott C., Zhang L., Teodoro T., Ravazzola M., Volchuk A. Chronic palmitate but not oleate exposure induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, which may contribute to INS-1 pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3398–3407. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eizirik D.L., Sammeth M., Bouckenooghe T., Bottu G., Sisino G., Igoillo-Esteve M. The human pancreatic islet transcriptome: expression of candidate genes for type 1 diabetes and the impact of pro-inflammatory cytokines. PLoS Genetics. 2012;8(3):e1002552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cnop M., Abdulkarim B., Bottu G., Cunha D.A., Igoillo-Esteve M., Masini M. RNA sequencing identifies dysregulation of the human pancreatic islet transcriptome by the saturated fatty acid palmitate. Diabetes. 2014;63:1978–1993. doi: 10.2337/db13-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ortis F., Naamane N., Flamez D., Ladrière L., Moore F., Cunha D.A. Cytokines interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulate different transcriptional and alternative splicing networks in primary beta-cells. Diabetes. 2010;59:358–374. doi: 10.2337/db09-1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dupraz P., Rinsch C., Pralong W.F., Rolland E., Zufferey R., Trono D. Lentivirus-mediated Bcl-2 expression in betaTC-tet cells improves resistance to hypoxia and cytokine-induced apoptosis while preserving in vitro and in vivo control of insulin secretion. Gene Therapy. 1999;6:1160–1169. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allison J., Thomas H., Beck D., Brady J.L., Lew A.M., Elefanty A. Transgenic overexpression of human Bcl-2 in islet beta cells inhibits apoptosis but does not prevent autoimmune destruction. International Immunology. 2000;12:9–17. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou Y.P., Pena J.C., Roe M.W., Mittal A., Levisetti M., Baldwin A.C. Overexpression of Bcl-x(L) in beta-cells prevents cell death but impairs mitochondrial signal for insulin secretion. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;278(2):E340–E351. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.2.E340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]