Abstract

Translation of research to practice often needs intermediaries to help the process occur. Our Prevention Research Center has identified a total of 89 residents of public housing in the last 11 years who have been working in the Resident Health Advocate (RHA) program to engage residents in improving their own and other residents’ health status, by becoming trained in skills needed by Community Health Workers. Future directions include training for teens to become Teen RHAs and further integration of our RHA program with changes in the health care system and in the roles of community health workers in general.

Keywords: community based participatory research, employment training, health promotion, community health workers

Introduction

Community health workers (CHW) are known by multiple labels; essentially, the common elements of all community health workers are that they are people drawn from the communities they serve to provide links between some aspect of health and human services to a community that, without that link, may not receive appropriate care, education, or support1,2. CHWs have been trained and employed in many settings and disease focused programs3,4, and evaluations indicate that CHWs are generally an efficacious way of providing a link between community members and services5. However, many of the specifics, on CHW training and activities are not known and are needed for enhancement of the CHW model6.

The Partners in Health and Housing Prevention Research Center (PHH-PRC), funded since 2001 by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is an equitable four-way partnership among researchers, community members, and public agencies. The four partners that make up the PHH-PRC are: (1) the Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH), an administrative and academic home for the Center; (2) the Community Committee for Health Promotion (CCHP), representing the residents of the Boston Housing Authority’s family housing developments; (3) the Boston Housing Authority (BHA), which houses about 10 percent of the city’s residents; and (4) the Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC), the city’s health department. This PHH-PRC’s mission is to improve the health and well-being of the residents of Boston’s public housing, and reduce health disparities, by engaging residents in community-centered research efforts and prevention activities. Thus the programs and the research of the PHH-PRC are closely intertwined. Moreover, as one of 37 Prevention Research Centers nationwide, the PHH-PRC is part of CDC’s nationwide network of academic researchers, public health agencies, and community members conducting applied research in disease prevention and control.

A cornerstone of the PHH-PRC is its Resident Health Advocate (RHA) training program. Now in its eleventh year, this PHH-PRC program annually trains a cohort of residents selected from submitted resident applicants within the BHA family housing portfolio to serve as health resources for their respective communities. Applicants enrolled in the training receive basic health information on diseases prevalent among public housing residents as well as the tools to discuss these conditions with their fellow residents and to guide them to health resources throughout the city of Boston. The impact of RHAs on residents’ use of available health services has received some research attention7. The purpose of this paper is to present an overview of the RHA recruitment and training program to present the results of ten years’ of recruitment and training into the program; and to give a feel for the diversity of RHAs in a program like this, who can be supported and trained for a wide variety of health-related activities.

Methods

Overview

Now in its eleventh year, the RHA Program trains and certifies a group of public housing residents as Resident Health Advocates each year. After completing training, RHAs were hired as paid interns by the Boston Housing Authority (BHA), and worked for six to eight months in their respective developments.

Annual Cycle of RHA Program Activities

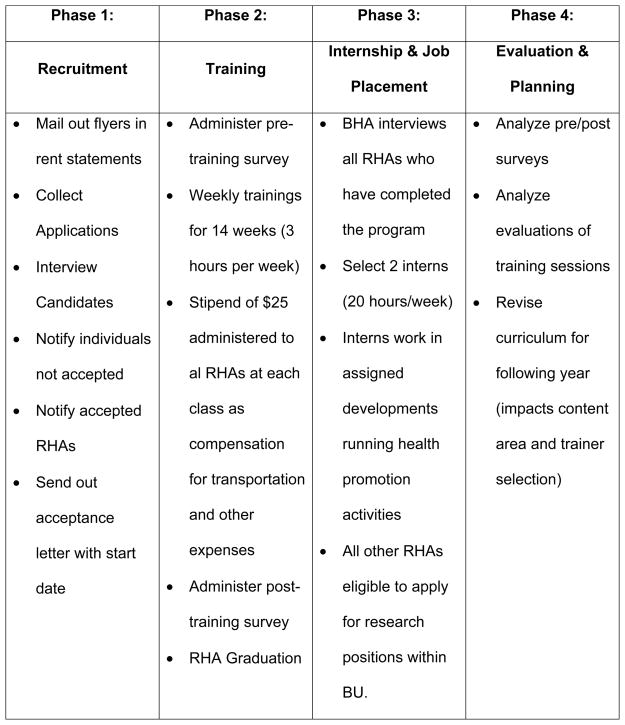

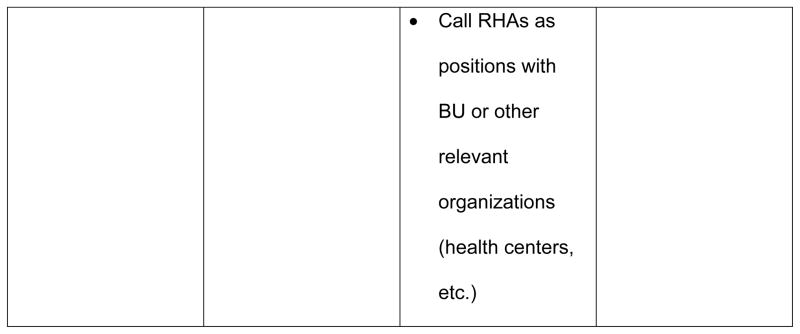

The RHA program followed an annual cycle of activities, consisting of recruitment, training, internship, and evaluation, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Phases of RHA Engagement

(a) Phase 1: Recruitment

The PHPhasH-PRC recruits for the RHA program every year in July. Flyers describing the RHA program and application instructions are developed with input from all PRC partners and printed by Boston University (the training arm of the PRC). The flyers are then sent to the Boston Housing Authority where they are included in monthly rent statements mailed to each head of household living in BHA family housing developments. In 2011, roughly 7,000 flyers were mailed to residents in the family housing developments. Residents are eligible to participate in the RHA program if they reside in one of the BHA family housing developments with 100 + units, (GED is preferred but not required) and if they are following the terms of their lease or lease complaint.

Applications were available to all residents at each management office. The application is designed to identify residents who have a strong interest in health and community outreach. The application required residents to describe their past education, employment and volunteer experience. Additionally, all applicants were asked to write a short essay explaining their motivation for joining the RHA training program. Finally, to demonstrate involvement in their respective development and/or communities, each applicant was required to provide three references, including one from the housing development’s management and one from a community group or formal tenant organization in the housing development.

Candidates were ranked on the strength of five separate components of their applications. PHH-PRC staff took the following into account when deciding which individuals to interview:

Appropriate completion of application

Education requirement

Work/Volunteer Experience

Personal Statement

Personal/Professional References

Most recently in 2011, the PHH-PRC had 15 RHA positions available, 48 applications were received, 23 applicants were interviewed, and 14 applicants were chosen to participate in the program.

(b) Phase 2: Training

PHH-PRC staff designed and implemented the training portion of the RHA program. The RHA training began in early September and ran for 14 weeks (through December), with weekly four-hour sessions led by experts from the Boston Public Health Commission’s Community Health Education Center (CHEC), the Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH), and other public health agencies throughout the city of Boston. RHAs received a weekly stipend of $25.00 to offset the cost of transportation and other minor expenses.

During their training, RHAs learned basic information about health conditions that disproportionately burden residents of public housing such as asthma, the effects of smoking and impact of obesity and related conditions. The health related topic content for each session of the 14-week training varied slightly each year. For example, the 2011 curriculum emphasized chronic disease as a key content area because our current knowledge base and research indicated a high burden of disease among Boston’s public housing population. In addition to education in specific health conditions, training covered such topics as leadership and advocacy, cultural competence and community organizing. Finally RHAs became acquainted with local health resources, including community health centers, to which they can refer their neighbors and fellow residents. In December, at the end of their training, RHAs were given a resource manual, which identified key health promotion organizations within the city of Boston and described the services or resources they can provide. PRC staff complete a formal evaluation of each RHA trainee including a recommendation as the appropriateness/readiness of the individual for work in the internship.

(c) Phase 3: Internship

The Boston Housing Authority (BHA) was in charge of the internship portion of the RHA program. For the first 10 years of the program, upon completion of the 14-week training period, RHAs who successfully completed training were hired automatically by the BHA to complete internships in their respective housing developments. These internships offered RHAs the opportunity to put their new skills into practice. The RHAs were paid to work up to six hours per week for a period of six to eight months. Examples of RHA internship activities included:

Developing/implementing workshops in their respective developments

Distributing and collecting health surveys for an annual survey by the PHH-PRC’s Community Committee for Health Promotion

Inviting and scheduling providers of primary health care services to attend Boston Housing Authority Unity Days, which are summer celebrations where residents get together and service providers are invited to promote their services & programs.

RHA interns had office space provided by the BHA or a tenant organization, and they reported to a staff person located at the BHA.

The internship was originally intended to help RHAs transition into the full-time workforce, by providing work experience as well as a small income over a period of several months. However, in 2011 it was decided that a more meaningful job training experience could be provided to RHAs in the form of a more intensive internship. Therefore, it was decided that the BHA would instead hire two RHAs to each work 20 hours per week and provide services to multiple developments during the six to eight month internship period.

In 2011, after completion of the training all the participants were given the opportunity to apply for the 2 part-time positions within the BHA. The process of applying was considered an optional part of their training. Applicants were required to have a resume and be interviewed by BHA staff. After the interviewing process, all applicants were provided with feedback on how they performed during the interview. The two RHAs hired as interns were assigned to provide services to several developments, not just those in which they lived. RHAs not hired were eligible to work on other research projects, participate in focus groups, and complete other work with both the PRC and other academic and community organizations looking to utilize their unique skill set. The PHH-PRC intends to use this model again in the 2012/13 programmatic cycle.

(d) Phase 4: Evaluation

The RHA program was evaluated each year through multiple methods. RHAs are surveyed after individual training sessions to assess the impact of the trainers and RHA satisfaction with the quality of information provided to them. These evaluations reviewed the design of the training curriculum for the following year. The internship was also evaluated through a baseline and post-training survey, which gathered information on RHA self-efficacy, knowledge gained, and skills confidence. Community impact was evaluated through weekly activity logs filled out by each RHA. Finally an annual survey of current and former RHAs asked about employment status and the impacts of the RHA program. As noted earlier, each RHA trainee is formally evaluated by the PRC staff prior to advancing to the internship phase.

Results

Table 1 provides the background data for all RHAs who participated in the RHA training offered by the PRC. As seen in this table, residents came from diverse backgrounds. Most were women and majority of them were between 20 and 40 years of age. About half of the trainees spoke a primary language other than English, and the languages spoken were diverse, similar to the languages spoken by residents of public housing in general. Having a high school degree or working towards a high school or GED equivalent was a requirement of entering the training program, as reflected in the educational levels of the individuals. The large numbers of missing data were due to the fact that not all information was collected consistently across all years.

Table 1.

Demographic Data for RHAs enrolled in RHA training program 2002 – 2012 (N= 95)

| Gender | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 9 | 9.5 |

| Female | 86 | 90.5 |

| Age | ||

| 19 – 24 | 7 | 7.4 |

| 25 – 34 | 15 | 15.8 |

| 35 – 44 | 13 | 13.7 |

| 45 – 54 | 9 | 9.5 |

| 55 – 64 | 2 | 2.1 |

| 65+ | 1 | 1.1 |

| Unknown | 48 | 50.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino/Chicano | 42 | 44.2 |

| African American/Black | 43 | 45.3 |

| White/Caucasian | 7 | 7.4 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 | 3.2 |

| Other | 1 | 1.1 |

| English as a second language | ||

| Main Language other than English | 47 | 49.5 |

| Language Distribution ( as % of total RHA trainees) | ||

| Chinese | 2 | 2.1 |

| French | 4 | 4.2 |

| Haitian Creole | 8 | 8.4 |

| Italian | 1 | 1.1 |

| Luo | 2 | 2.1 |

| Spanish | 36 | 37.9 |

| Somali | 1 | 1.1 |

| Swahili | 2 | 2.1 |

| Vietnamese | 2 | 2.1 |

| Education Level | ||

| Unknown | 22 | 23.2 |

| Elementary School | 0 | 0.0 |

| Middle School/ Junior High | 0 | 0.0 |

| Some High School | 1 | 1.1 |

| High School/ GED | 22 | 23.2 |

| Some Undergrad Level | 22 | 23.2 |

| Associates Degree/Certificate Program | 19 | 20.0 |

| Bachelors Degree | 8 | 8.4 |

| Graduate Level | 1 | 1 |

Table 2 provides an overview of recruitment of RHAs into the program over the last 10 years. As seen in this table, each year there were more applicants than slots for the training program, indicating the desire for this type of training and job assistance program in public housing. These data indicate that the majority of the trainees completed the training, and graduated from the program. The majority of the trainees offered internships completed them, applying their newly learned skills in housing developments; however, a number of trainees left their internships early in order to take a job. In 2009–2010, we offered the RHA training program but changed the design to fewer internship slots that were more in depth than previous years, reducing the number of graduates who continued to internships.

Table 2.

Enrollment, training, and internship of Resident Health Advocates in Boston’s public housing 2002–2012.

| Year | # Applications Received | # Enrolled Training | # (%)Completed Training | # Offerred Internship | # (%)Completed Internship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002/03 | 18 | 13 | 12 (92.3) | 12 | 12 (92.3) |

| 2003/04 | 16 | 11 | 10 (90.9) | 10 | 8 (80.0) |

| 2004/05 | 16 | 9 | 8 (88.9) | 8 | 3 (37.5) |

| 2005/06 | 35 | 12 | 12 (100.0) | 12 | 10 (83.3) |

| 2006/07 | 35 | 10 | 10 (100.0) | 10 | 10 (100.0) |

| 2007/08 | 30 | 10 | 9 (90.0) | 9 | 8 (88.9) |

| 2008/09 | 36 | 10 | 10 (10.0) | 10 | 7 (70.0) |

| 2010/11* | 51 | 8 | 7 (87.5) | 7 | 4 (57.1) |

| 2011/12 | 48 | 14 | 11 (78.6) | 2** | 2 (100.0) |

| TOTAL | 285 | 97 | 89 (91.8) | 80 | 64 (80.0) |

RHA Training model changed in 2009/10 (Advanced RHA Training run instead); 5 applications were received and 4 were trained;

2011/12 cycle underwent programmatic revision and 2 RHAs selected as BHA interns

Paths taken by former RHAs

The original intent of PRC researchers was that the RHA program would be a bridge to higher education or to full employment for at least some Resident Health Advocates, through a formal arrangement with an undergraduate institution. Several RHAs have in fact gone on to degree programs, as seen in Table 3. In Table 3, although RHA training is not the first step on a formal career ladder, most former RHAs who wanted to work in the health care sector were in fact employed—for example, some RHAs have found work as medical assistants and nursing assistants. One RHA has become a unit coordinator at a hospital. Finally, several former RHAs now work on the PRC’s own research projects—for example, as dental RHAs, after additional training in oral health, or as research assistants on the intervention study of the RHA program itself, after receiving training in the research protocol.

Table 3.

RHA Post Training Data 2007–2012 (N= 51)

| # | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Further Education (ever) | 25 | 49.0 |

| Further Employment (ever) | 39 | 76.5 |

| Further Employment Public Health (ever) | 27 | 52.9 |

| Volunteering (ever) | 20 | 39.2 |

| Volunteering Public Health (ever) | 9 | 17.6 |

| Moved out of BHA/Section 8 | 10 | 19.6 |

Discussion

The RHA Program has produced three clear benefits. First, during the internship that follows their training, RHAs provided a service to their own communities by sharing what they have learned about health and health care with other residents of their own housing developments. Indeed, part of the original rationale for the RHA program was that public housing residents would be more comfortable discussing personal health issues with other residents than with outside experts. Second, the RHA training and internship experience gives RHAs support in getting work or additional education in health care. A third benefit, closely related to the second, is workforce development as the RHA graduates will be well prepared to move into jobs in health care or related human services that offer further training and development, and opportunity for advanced degrees. It also provides an additional training opportunity for RHAs who have been effective in this role, but who have not moved directly into jobs after their initial internship. The advanced RHA program, in particular, enlarges and enriches the pool of workers trained for jobs in health care.

Insights from the RHA program

From our current vantage point several years into the RHA Program, we offer two key elements that have contributed to the success of the program, and also identify two lessons learned that others may find useful in developing successful RHA-style programs.

Build trust through a collaborative approach

Over the period of eleven years, the RHA program has taken root in several housing developments. The trust of residents, which is essential to a successful RHA program, takes time to develop and often begins with personal connections. For example, members of the PRC’s Community Committee for Health Promotion have been instrumental in the program, as have individuals at the PRC’s partner agencies who had already earned the trust of residents through years of hard work and engagement. Thus the collaborative structure of the PRC has made it possible to develop trust and a working relationship with residents. In addition, the presence of a tenant task force in a development, along with individuals who have well-established links to the task force, have been important to successfully establishing and maintaining the RHA model.

Define a research question that builds trust and is clearly useful

Another important factor in earning the trust of a socially disadvantaged population has been the respect for public housing residents that is embedded in the research design. In the evaluation of the impact of RHAs, for example, the public health intervention was narrowly defined and was developed from a program that reflected best practice in public health and provided a clear benefit to all residents. Thus all residents of a set of housing developments were provided health information about important chronic diseases, and all had access to a health van that offered screening for hypertension, diabetes, and dental disease, with links to clinical follow-up as needed. The RHAs involved in this specific program loved it and remained employed with us because they could relate to the topic and the need in their communities.

Plans for the future

As described above, for the first 10 years of the program, after RHAs completed their training they moved into paid internships, working six hours per week for six to eight months. During this period the RHAs were paid by the Boston Housing Authority, with funds from the PHH-PRC, and each was supervised by a BHA staff member. After completion of training of the RHAs by BUSPH PRC partner, RHAs were effectively transitioned into the internship by conducted by the BHA. In retrospect, it would have been helpful for the research institution to stay more involved in the internship phase, so that the RHAs’ transition to job-like status would be more gradual. In addition, such an arrangement would allow the collection of data to evaluate the internship. For example, we need to know if residents are coming to the RHAs with questions? If not, why not? Would a longer and more intensive internship be more effective?

Many public housing developments have a Tenant Task Force that works closely with residents, the BHA, and outside organizations to build a community within the development. As part of the RHA initiative, PRC representatives met with the Tenant Task Force once a year, at the time the RHA cycle began. Again, in retrospect it would have been helpful to researchers to build a deeper relationship with these trusted community members, who have a special stake in a particular housing development.

The PHH-PRC is in support of other housing authorities seeking to replicate. the RHA program. Municipal housing authorities in other cities and states may find the Resident Health Advocate program an attractive model for enhancing residents’ health knowledge and their use of health services. To these housing authorities, we offer the collaborative approach used in Boston as a model to help a new RHA program achieve its fullest potential.

Involving a municipal health department brings access to health data, a wealth of knowledge about local health concerns and health programs, and access to specific resources. As one concrete example, in the RHA program evaluation described above, the health van was provided by the Boston Public Health Commission, a direct benefit of the collaborative approach used in the research project. The use of the van in this effort also served a goal of the Boston Public Health Commission to increase the use of the health van at housing developments.

In developing and assessing an RHA program, a housing authority will also benefit by involving a nearby academic institution, which can bring expertise and research dollars that could improve residents’ quality of life. This type of program development and program assessment work also provides a rich training ground for students in public health, community development, or community-based participatory research. Their work as students benefits an RHA program directly, while enhancing their own professional training.

Finally, including the community as a full partner has been a key element in the success of the RHA program in Boston’s family housing developments. The Community Committee for Health Promotion had a major role in designing and implementing the RHA program. Focus groups in which, community members are queried about access to health services or barriers to using services are helpful, but they only begin to tap the community wisdom that is essential to designing and implementing effective programs and program evaluations. The path to a full partnership may be gradual: for example, using focus groups as a starting point, a housing authority might identify key informants, and then create an advisory community committee, and then expand this committee’s role into that of a full partner. An experienced, dynamic leader with strong roots in the community is a great asset to such a committee, and to the collaboration as a whole.

Acknowledgments

This journal article is a product of a Prevention Research Center and was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 5 U48 DP0019-22 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings and conclusions in this journal article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Deborah J Bowen, Email: dbowen@bu.edu.

Sarah Gees Bhosrekar, Email: sgees@bu.edu.

Jo-Anna Rorie, Email: jrorie@bu.edu.

Rachel Goodman, Email: rachel.goodman@bostonhousing.org.

Gerry Thomas, Email: gthomas@bphc.org.

Nancy Irwin Maxwell, Email: nmaxwell@bu.edu.

Eugenia Smith, Email: emsmith@bu.edu.

References

- 1.Wells KJ, Luque JS, Miladinovic B, et al. Do community health worker interventions improve rates of screening mammography in the United States? A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(8):1580–1598. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peretz PJ, Matiz LA, Findley S, Lizardo M, Evans D, McCord M. Community health workers as drivers of a successful community-based disease management initiative. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):1443–1446. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey I, Schulz A, Israel B, et al. The Healthy Connections project: a community-based participatory research project involving women at risk for diabetes and hypertension. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2009;3(4):287–300. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colleran K, Harding E, Kipp BJ, et al. Building capacity to reduce disparities in diabetes: training community health workers using an integrated distance learning model. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(3):386–396. doi: 10.1177/0145721712441523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balcazar HG, Byrd TL, Ortiz M, Tondapu SR, Chavez M. A randomized community intervention to improve hypertension control among Mexican Americans: using the promotoras de salud community outreach model. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(4):1079–1094. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arvey SR, Fernandez ME. Identifying the core elements of effective community health worker programs: a research agenda. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1633–1637. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rorie J-A, Smith A, Evans T, et al. Using resident health advocates to improve public health screening and follow-up among public housing residents, Boston, 2007–2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(1):A15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]