Abstract

Secondary lymphoid organs (SLO) provide the structural framework for co-concentration of antigen and antigen-specific lymphocytes required for an efficient adaptive immune system. The spleen is the primordial SLO, and evolved concurrently with Ig/TCR:pMHC-based adaptive immunity. The earliest cellular/histological event in the ontogeny of the spleen’s lymphoid architecture, the white pulp (WP), is the accumulation of B cells around splenic vasculature, an evolutionarily conserved feature since the spleen’s emergence in early jawed vertebrates such as sharks. In mammals, B cells are indispensable for both formation and maintenance of SLO microarchitecture; their expression of lymphotoxin α1β2 (LTα1β2) is required for the LTα1β2:CXCL13 positive feedback loop without which SLO cannot properly form. Despite the spleen’s central role in the evolution of adaptive immunity, neither the initiating event nor the B cell subset necessary for WP formation has been identified. We therefore sought to identify both in mouse. We detected CXCL13 protein in late embryonic splenic vasculature, and its expression was TNFα- and RAG-2-independent. A substantial influx of CXCR5+ transitional B cells into the spleen occurred 18 hours before birth. However, these late embryonic B cells were unresponsive to CXCL13 (though responsive to CXCL12) and phenotypically indistinguishable from blood-derived B cells. Only after birth did B cells acquire CXCL13 responsiveness, accumulate around splenic vasculature, and establish the uniquely splenic B cell compartment, enriched for CXCL13-responsive late transitional cells. Thus, CXCL13 is the initiating component of the CXCL13:LTα1β2 positive feedback loop required for WP ontogeny, and CXCL13-responsive late transitional B cells are the initiating subset.

Introduction

The spleen is the primordial secondary lymphoid organ, which evolved concurrently with Ig/TCR:pMHC-based adaptive immunity (1). It provides the structural framework necessary for the co-concentration of antigen and antigen specific lymphocytes required for an efficient adaptive immune system (2). The spleen is unique among secondary lymphoid organs in its functional and histological segregation into two discrete areas: the red pulp (RP) and the white pulp (WP) (3). The RP is tasked with filtration of the blood, including removal of effete erythrocytes and free heme for iron recycling, as well as bacterial capture and clearance; the WP is the spleen’s lymphoid component. The early events in the ontogeny of the splenic WP are conserved since the appearance of the spleen itself in early jawed vertebrates approximately 500 million years ago (MYA); B cell accumulation around splenic vasculature marks the onset of WP ontogeny in the neonatal nurse shark Ginglymostoma cirratum (4). In the spleen of the adult nurse shark, B cells remain vasculature-associated, with T cells peripheral to the follicle (unpublished). This is also the case in the adult African clawed frog Xenopus laevis (common ancestor with humans approximately 350MYA) (5).

In the mouse, the WP comprises a central arteriole, a periarteriolar lymphoid sheath (PALS) of T cells (the T cell zone), one or more adjacent B cell follicles, and a surrounding marginal zone populated by a specific subset of B cells and two distinct populations of macrophages (3,6). While the microarchitecture of the mature mammalian splenic WP does not retain the early developmental features like in cold-blooded vertebrates, mouse WP ontogeny also begins with the accumulation of B cells around splenic vasculature within 48 hours after birth and their subsequent contraction into a nascent follicle (7). This is followed by an accumulation of T cells around the splenic vasculature central to the nascent follicle and the appearance of the marginal zone within 96 hours of birth, and ultimately the displacement of the B cell follicle from the vasculature by the PALS.

The microarchitecture of both the mouse B cell follicle and the WP as a whole are dependent upon a positive feedback loop in which B cell-derived lymphotoxin (LT) α1β2 promotes CXCL13 production by follicular dendritic cells (FDC) via the LTβR. CXCL13, in turn, induces LTα1β2 expression on B cells via CXCR5 (8). This CXCL13/LTα1β2 positive feedback loop is also necessary for proper T cell zone (9) and MZ establishment (10). Lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells are also a significant source of LTα1β2, and while they are necessary for the formation of lymph nodes and Peyer’s Patches, LTi cells are dispensable for establishment of the splenic WP (11,12). In addition to LTα1β2, B cell-derived TNFα is required for both WP microarchitecture and maintenance of FDC networks within the follicle (13–15), though the precise role and timing of TNFα are yet to be elucidated (16,17). Genetic ablation of any member of this pathway results in an inability of the WP to form properly (18,19) (though it has recently been reported that in the absence of LTα1β2, overexpressed TNFα alone is sufficient to promote WP ontogeny and microarchitecture (20)), and disruption of this pathway results in a loss of established WP integrity (21,22).

Dramatic changes in B lymphopoiesis occur at birth, in parallel with the onset of WP ontogeny. The primary site of B lymphopoiesis shifts from the fetal liver, which, along with the yolk sac and paraaortic splanchnopleura, preferentially produces B-1 B cells, to the bone marrow, which preferentially produces conventional (B-2) B cells (23). As B cells, because of their ability to express LTα1β2 in response to CXCL13 stimulation, are indispensable for the formation and maintenance of the WP, a fundamental question arises: which lineage and/or subset of B cells is responsible for the initiation of WP ontogeny? In this paper, we seek to identify the B cell subset that seeds the splenic WP, as well as the initiating member of the CXCL13/LTα1β2 positive feedback loop required for the WP’s ontogeny and maintenance. We also synthesize recent and long-standing data into a coherent and progressive model for the early events in the ontogeny of the mammalian splenic WP.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Adult female (12–16 weeks) and timed-pregnant C57Bl/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, for arrival in our facility at E5. Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at the University of Maryland until indicated developmental timepoints. All animal experiments were conducted under the guidelines and approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Spleens from TNFa−/− embryos and pups (C57Bl/6 background) were generously provided by Giorgio Trinchieri (NIH), and spleens RAG2−/− embryos and pups (C57Bl/6 background) were generously provided by Kyle Wilson (UMB).

Immunohistochemistry

Spleens were excised, immediately frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound (Sakura) and sectioned at 6uM on a CM3050S microtome (Leica). Sections were fixed in acetone, blocked in 5% non-fat milk in PBS-T, and stained for 2hr. at 4C with indicated antibody: IgM (R6-60.2), CD23 (B3B4) (BD Biosciences), SMA (1A4) (Sigma), CXCL13 (polyclonal), goat IgG (polyclonal) (R&D Systems), and IgM (eB121-15F9) (eBioscience). Sections were analyzed on an Eclipse E800 microscope (Nikon) using a Spot RT3 camera (Diagnostic Instruments), and analyzed with Spot Advanced software. Images were adjusted for brightness and contrast using Adobe Photoshop Elements (Adobe Systems Inc.).

Flow Cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared from pooled embryonic or neonatal spleens (3–5 spleens per sample) or adult spleen by mechanical dissociation in PBS + 2% FCS + 0.1% NaN3. Blood was collected from embryos/pups by decapitation and collection of blood in PBS + 200U/mL Heparin (Sigma). Erythrocytes were lysed in ACK Lysis Buffer (Gibco, Life Tecnhologies). Cells were stained with indicated antibody: IgM (R6-60.3), CD19 (1D3), CXCR5 (2G8), CD93 (AA4.1), CD9 (KMC8), CD5 (53-7.3) (BD Biosciences), and CD23 (2G8) (Cell Lab), on ice in PBS + 2% FCS + 0.1% NaN3, and analyzed in PBS + 0.1% NaN3 on an LSRII flow cytometer with FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences), and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

In situ Hybridization

Spleens were excised and fixed O/N in 4% PFA at 4C, equilibrated in 30% sucrose, and frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound (Sakura), then sectioned at 6uM on a CM3050S microtome (Leica). In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (24). DIG-labeled riboprobe for CXCL13 was generated using forward primer 5’-AGGTTGAACTCCACCTCCAG-3’ and reverse primer 5’-GGTGCAGGTGTGTCTTTTG-3’, and DIG-labeled riboprobe for PDGFRβ was generated using forward primer 5’-CCTCAAAAGTAGGTGTCCACG-3’ and reverse primer 5’-CAGGTTGACCACGTTCAGGT-3’

Migration Assay

Single cells suspensions from pooled E18.5 or P0.5 spleens (3–5 per sample) or adult spleen were prepared by mechanical dissociation in RPMI + 10% FCS, Pen/Strep, Sodium Pyruvate, L-Glutamine, and 2-mercaptoethanol. Erythrocytes were lysed by hypotonic shock. Adult blood was collected in PBS + 100U/mL heparin. Leukocytes were isolated over Lymphocyte Separation Medium (Corning) and suspended in RPMI + 10% FCS, Pen/Strep, Sodium Pyruvate, L-Glutamine, and 2-mercaptoethanol. 1 million cells per well were loaded into the upper chamber of a Transwell insert (5uM polycarbonate membrane, 6.5mm insert diameter) (Costar), and either 1ug/mL recombinant CXCL13 or 100ng/mL recombinant CXCL12 (R&D Systems) was added to the lower chamber. Cells were incubated 8 hours for CXCL13, 4 hours for CXCL12 at 37C, 5% CO2. Cells in the lower chamber were then counted, stained (as above) with antibody against CD19 (1D3), IgM (R6-60.3), CD93 (AA4.1) (BD Biosciences), and CD23 (2G8) (Cell Lab), and analyzed by flow cytometry as above.

Calcium Mobilization Assay

Single cell suspensions from pooled E18.5 or P0.5 spleens (3–5 per sample) or adult spleen were prepared by mechanical dissociation in RPMI + 10% FCS, Pen/Strep, Sodium Pyruvate, L-Glutamine, and 2-mercaptoethanol. Erythrocytes were lysed by hypotonic shock. 1 million cells per sample were loaded with Fluo-5F_AM (Life Technologies) and incubated at 37C, 5% CO2 for 15 minutes. Antibody was added to each sample, IgM (R6-60.2) (BD Biosciences), and samples were incubated an additional 15 minutes at 37C, 5% CO2. Cells were analyzed for 30 seconds on an LSRII flow cytometer using FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences) prior to addition of 1ug/mL recombinant CXCL13 (R&D Systems), then analyzed for an additional 2 minutes. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software).

Results

Cellular/histological onset of WP ontogeny after birth

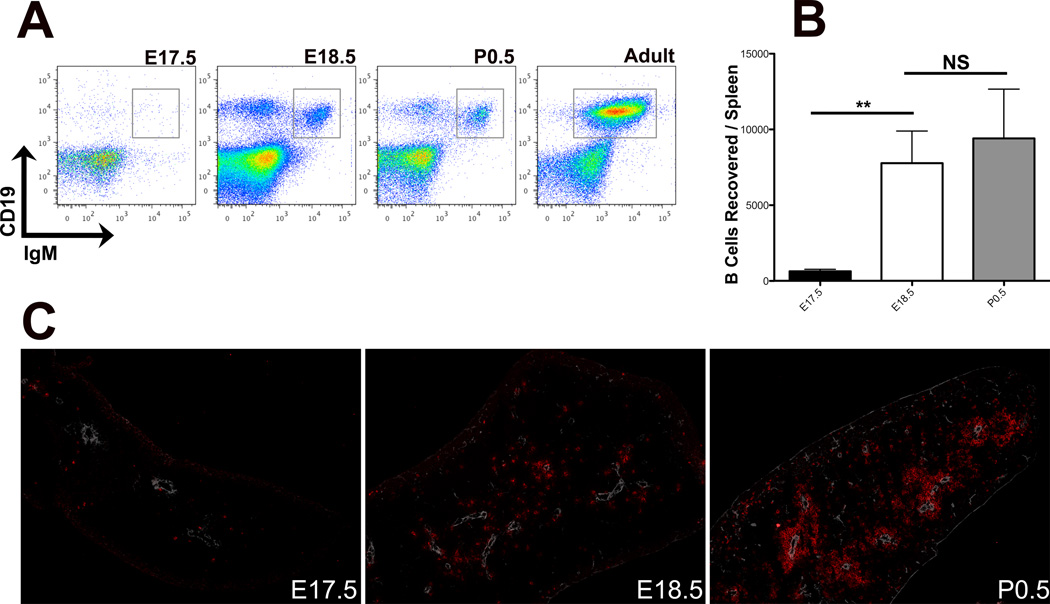

In order to precisely determine the timing of the cellular/histological onset of white pulp (WP) ontogeny, we analyzed splenocytes and splenic cryosections from E17.5 through P0.5 C57Bl/6J mice (partum E19.25). At all timepoints analyzed, two distinct populations of CD19+ B lineage cells were detected by FACS: an IgM− population consisting of CD43+ IgD− (not shown) pro-/pre-B cells, and an IgM+ population (Figure 1A); all subsequent analyses focus exclusively on the latter population of IgM+ B cells. Between E17.5 and E18.5, splenic B cell numbers increased approximately 10-fold (Figure 1B), then remained relatively constant between E18.5 and P0.5. This increase in splenic IgM+ B cells was accompanied by a reduction in the proportion of IgM+ B cells in the liver (not shown).

Figure 1. B cell population dynamics in the perinatal spleen.

(A) FACS analysis of perinatal splenocytes to show relative proportions of CD19+IgM− pro-/pre-B cells and CD19+IgM+ B cells (boxed in grey), gated on all cells. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (B) IgM+ B cells recovered per spleen at indicated developmental timepoints, n=5 at each timepoint. (C) IHC analysis of 6μM sections of perinatal (E17.5 – P1.5) spleens showing relative positioning of IgM+ B cells (red) and vasculature, stained with smooth muscle actin (SMA, white). 100× magnification, data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

At E17.5, the spleen consists entirely of red pulp, throughout which the few B cells detected were scattered randomly (Figure 1C). After the influx of B cells at E18.5, the cells remained randomly distributed throughout the spleen (Figure 1C). Though B cell numbers did not increase significantly between E18.5 and P0.5 (Figure 1B), by the early neonatal timepoint the majority of splenic B cells had aggregated around the splenic vasculature. As such, aggregation of B cells around the splenic vasculature at P0.5 marks the cellular/histological onset of WP ontogeny.

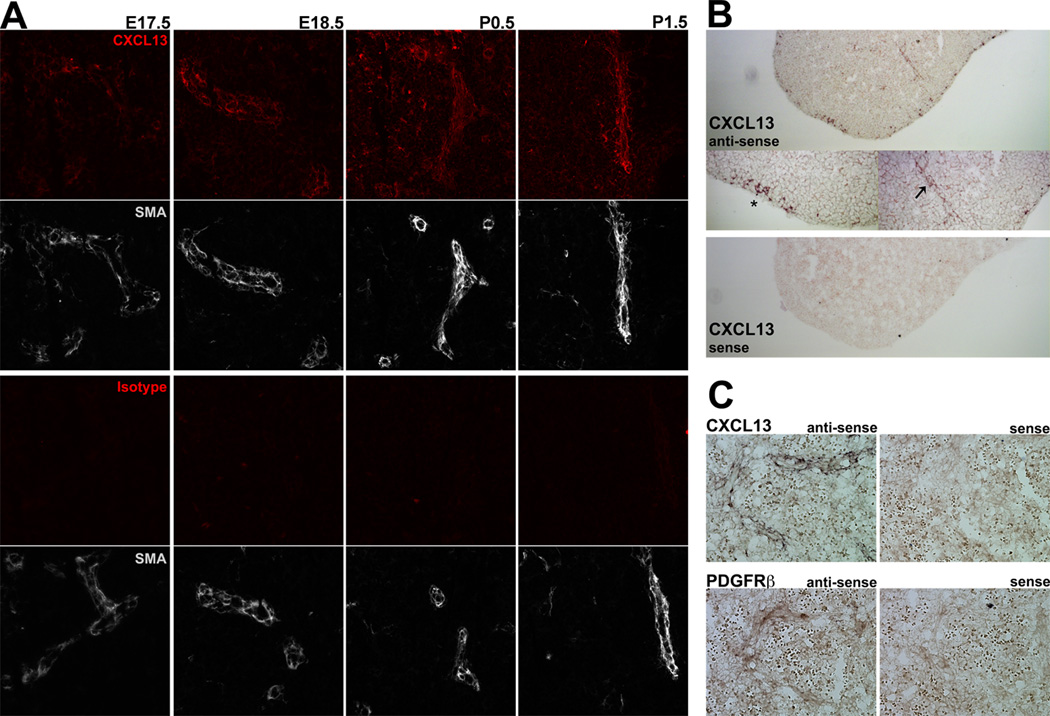

Perivascular CXCL13 expression precedes perivascular B cell aggregation

B cell homing to and retention in lymphoid follicles is dependent upon the chemokine CXCL13 and its B cell-expressed receptor, CXCR5 (25). While CXCL13 mRNA has been detected in extracts from whole embryonic spleen (7), CXCL13 protein production has not been previously observed. As perivascular B cell aggregation did not occur until birth, we predicted that CXCL13 protein would be undetectable until birth. However, CXCL13 protein was detectable around the splenic vasculature as early as E17.5 (Figure 2A). To determine whether the perivascular CXCL13 protein was produced locally by perivascular cells or had accumulated in the perivascular extracellular matrix after production elsewhere, we analyzed E18.5 splenic sections by in situ hybridization (ISH) and detected CXCL13 mRNA-expressing cells at the splenic vasculature (Figure 2B). Interestingly, we also observed CXCL13 mRNA-expressing cells in the subcapsular region of several (3 out of 7) spleens. However, subcapsular CXCL13 protein was not readily detectable by IHC (due to high fluorescent background at the tissue edges). We are currently endeavoring to identify these cells and determine their ability to produce CXCL13 protein.

Figure 2. CXCL13 expression by pre-FDC in the late embryonic spleen.

(A) IHC analysis of 6uM sections of perinatal (E17.5 – P1.5) spleens stained with anti-CXCL13 (red) and anti-smooth muscle actin (white) (upper panel), or isotype control (red) and anti-smooth muscle actin (white) (lower panel). 200× magnification, data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (B) In situ hybridization (100× magnification) analysis of CXCL13 expression, 6uM section of E18.5 spleen. Middle panels (200× magnification) showing both perivascular (arrow) and subcapsular (asterisk) expression of CXCL13. CXCL13-Sense probe control is shown in the bottom panel. (C) In situ hybridization (400× magnification) analysis of CXCL13 (upper panels) and PDGFRb (lower panels) expression in serial 6uM cryosections from E18.5 spleen. Sense control probes shown to the right; data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

The precursors of FDC have recently been identified as perivascular mural cells that coexpress the platelet derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ) and low levels of CXCL13 (26). ISH analysis of serial sections from E18.5 spleen revealed that the CXCL13-expressing cells coexpressed PDGFRβ, demonstrating that the low levels of CXCL13 in the late embryonic spleen are produced by pre-FDC (Figure 2C). Therefore, expression of both CXCL13 mRNA and protein by perivascular splenic pre-FDC precede aggregation of B cells around the splenic vasculature.

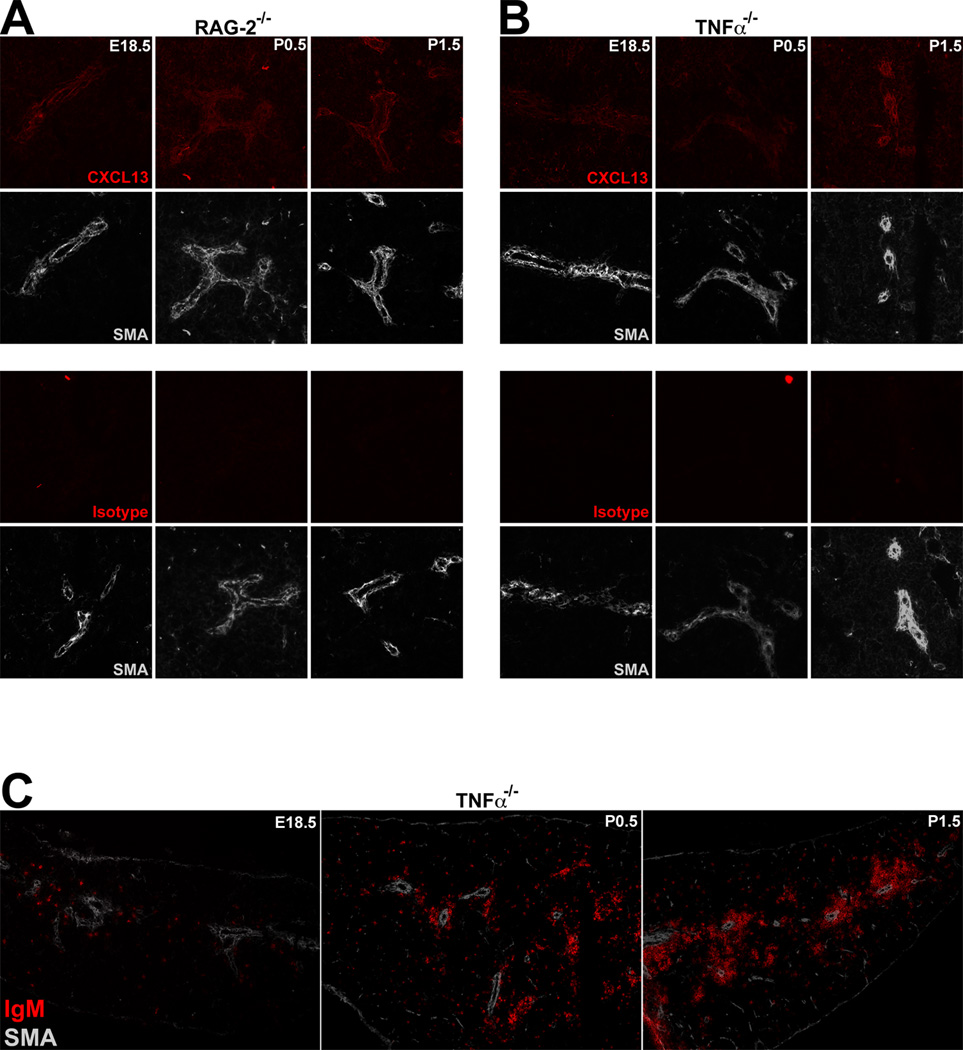

Embryonic CXCL13 expression is independent of TNFα and rearranging lymphocytes

Lymphotoxin (LT) α1β2 and TNFα are both necessary for maximal CXCL13 production in the splenic WP (27), and both are produced by radiosensitive hematopoietic lineage cells (14). LTα1β2 is not detectable in the spleen until birth (7, and not shown); as we detected CXCL13 mRNA and protein in the late embryonic spleen, LTα1β2 is dispensable for the initial induction of CXCL13. To determine the role of T/B cells in the initial induction of CXCL13, we analyzed spleens from E18.5 through P1.5 RAG-2−/− mice, and detected perivascular CXCL13 protein at all timepoints (Figure 3A). Additionally, we detected perivascular CXCL13 protein in TNFα−/− spleens at the same developmental timepoints (Figure 3B). These data demonstrate that initial induction of CXCL13 expression by splenic perivascular cells occurs independently of T and B cells, and of TNFα. However, despite both embryonic and neonatal perivascular expression of CXCL13, we observed a 24 hour delay in the aggregation of B cells around the splenic vasculature in the TNFα−/− spleens (Figure 3C), demonstrating a functional role for TNFα at the onset of WP ontogeny.

Figure 3. TNFα- and T/B cell-independent CXCL13 expression in the perinatal spleen.

(A) IHC analysis of 6uM sections of perinatal (E18.5 – P1.5) RAG-2−/− spleens stained with anti-CXCL13 (red) and anti-smooth muscle actin (white) (upper panel), or isotype control (red) and anti-smooth muscle actin (white) (lower panel). (B) IHC analysis of 6uM sections of perinatal (E18.5 – P1.5) TNFα−/− spleens stained with anti-CXCL13 (red) and anti-smooth muscle actin (white) (upper panel), or isotype control (red) and anti-smooth muscle actin (white) (lower panel). (C) IHC analysis of 6uM sections of perinatal (E18.5 – P1.5) TNFα−/− spleens stained with anti-IgM (red) and anti-smooth muscle actin (white). 200× magnification, data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

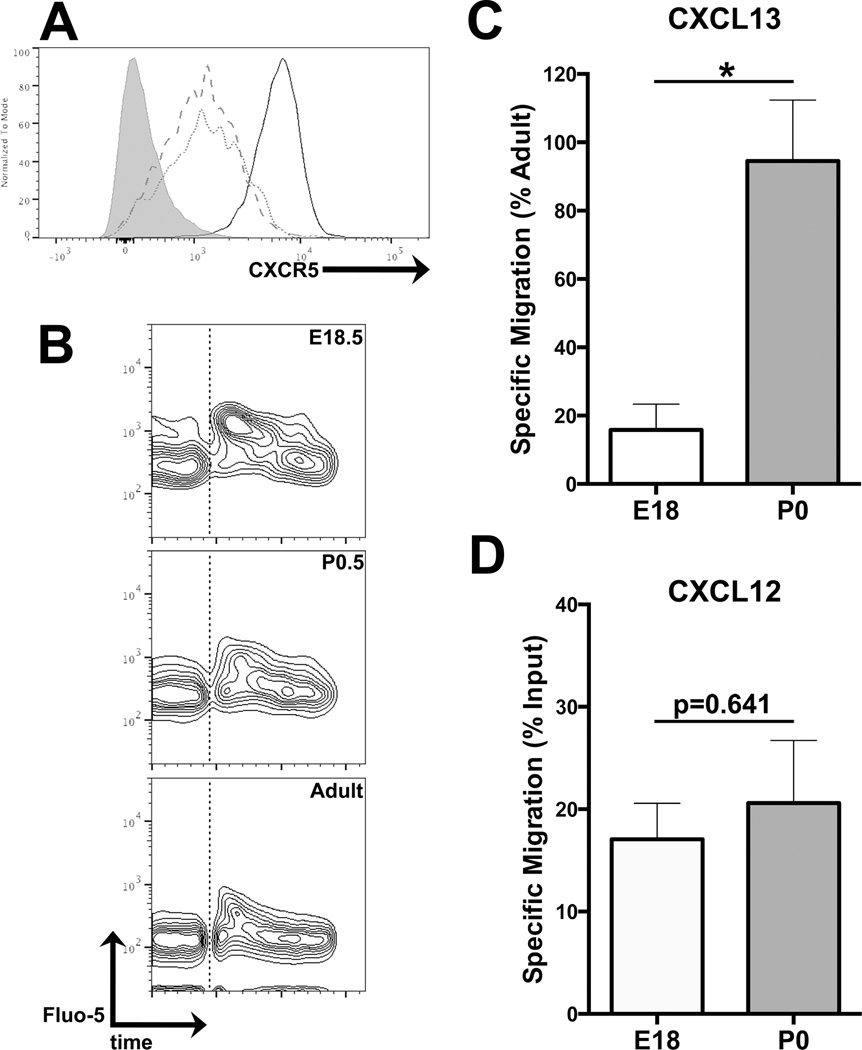

Differential responsiveness of E18.5 and P0.5 splenic B cells to CXCL13

The presence of CXCL13 protein around the late embryonic splenic vasculature prior to any localization of B cells to the CXCL13-expressing vasculature suggested a differential responsiveness of E18.5 and P0.5 splenic B cells to CXCL13. We therefore analyzed the relative levels of surface CXCR5 expression on splenic B cells from E18.5 and P0.5 mice (Figure 4A). Surface CXCR5 levels were indistinguishable between the two perinatal timepoints, though both were significantly lower than those observed on adult splenic B cells. We then analyzed the relative abilities of E18.5 and P0.5 splenic B cells to mobilize intracellular calcium in response to CXCL13 stimulation (Figure 4B), and found both populations competent to mobilize calcium.

Figure 4. Differential CXCL13 responsiveness in E18.5 and P0.5 splenic B cells.

(A) Surface CXCR5 expression levels on adult (solid line), P0.5 (dotted line), and E18.5 (dashed line) IgM+ B cells. CXCR5− shown in shaded grey. Gated on CD19+ IgM+ lymphocytes. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments. (B) Calcium mobilization in response to stimulation with 1ug/mL CXCL13. Chemokine addition marked with dotted line. Gated on IgM+ lymphocytes. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Transwell migration assay, showing specific migration of CD19+ IgM+ B cells in response to 1ug/mL CXCL13 (versus 1ug/mL BSA as control) relative to migration frequency of adult splenic B cells. n=3 for E18, n=9 for P0. (D) Transwell migration assay, showing specific migration of CD19+ IgM+ B cells in response to 100ng/mL CXCL12 (versus 100ng/mL BSA as control) relative to migration frequency of adult splenic B cells. n=3 for each.

Next, we analyzed the relative abilities of E18.5 and P0.5 splenic B cells to specifically migrate toward CXCL13 by Transwell assay (Figure 4C). P0.5 splenic B cells migrated at approximately the same frequency as adult splenic B cells. However, E18.5 splenic B cells showed a 6.3-fold reduction in the frequency of specific migration, despite their surface expression of CXCR5 at levels comparable to those observed on P0.5 B cells. To determine whether the E18.5 cells’ chemotactic unresponsiveness is restricted to CXCL13 or representative of a general impairment in chemokine-driven migration, we repeated the Transwell assay with CXCL12, towards which B cells of all developmental timepoints have been reported to migrate (28). Both the E18.5 and P0.5 B cells robustly migrated toward CXCL12 (Figure 4D), demonstrating that B cells from both developmental timepoints are capable of chemokine-driven migration, and suggesting a functional uncoupling of CXCR5 from the G protein receptor kinase (GRK)/arrestin/MAPK signaling cascade driving cellular chemotaxis (29).

Initiation of WP ontogeny by CXCL13-responsive late transitional B cells

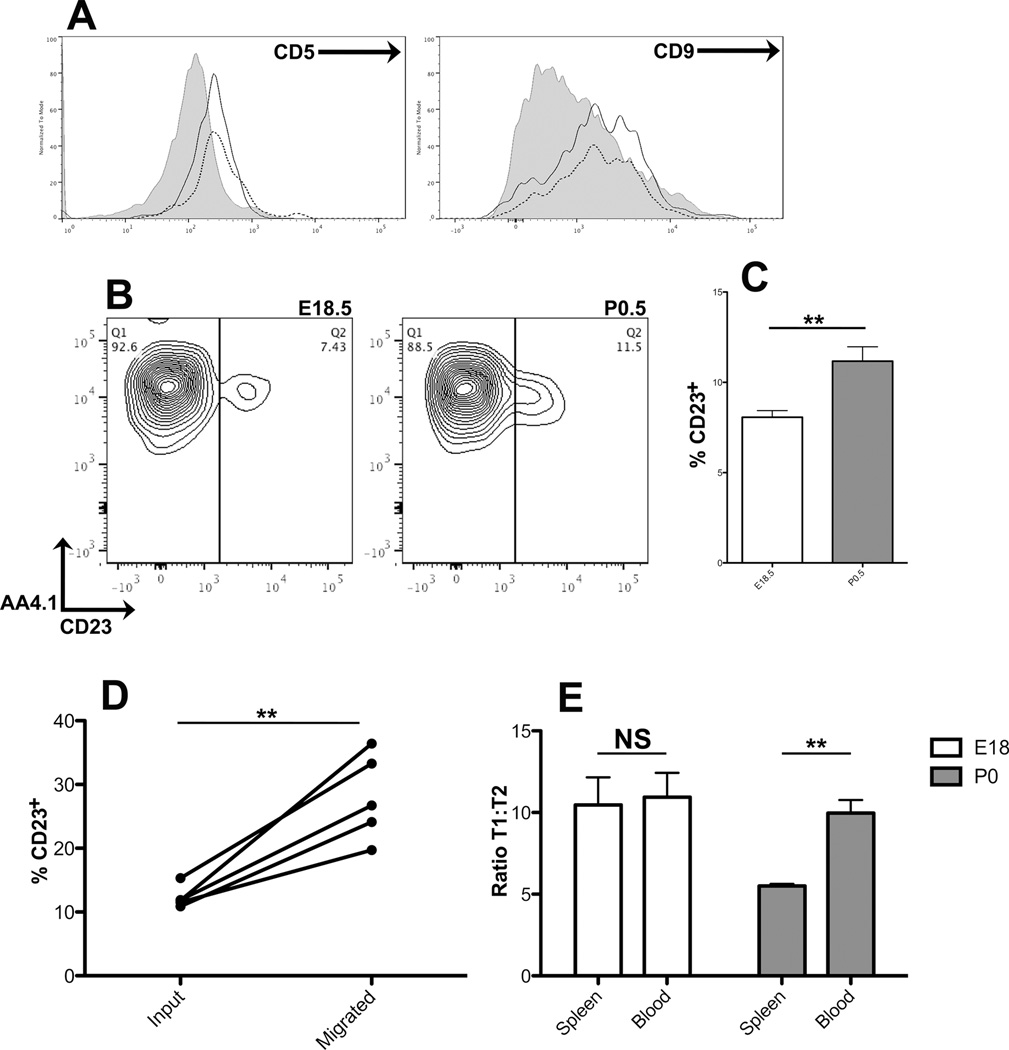

In order to identify potential differences among the perinatal splenic B cell populations that could explain their differential responsiveness to CXCL13, we further analyzed the IgM+ B cells from E17.5, E18.5, and P0.5 spleen. E17.5 splenic B cells were exclusively CD9+ CD5lo B-1a cells (Figure 5A) (30,31), while both the E18.5 and the P0.5 splenic B cells were exclusively AA4.1/CD93+ transitional (T) B cells (Figure 5B) (32,33). At both E18.5 and P0.5, the vast majority of cells were CD23− early transitional (T1) B cells, though a small proportion of CD23+ late transitional (T2) B cells was also detected, and between E18.5 and P0.5, the proportion of CD23+ T2 cells increased slightly but significantly (Figure 5C). Histologically, both CD23− and CD23+ IgM+ B cells were detected surrounding the vasculature in the P0.5 spleen (not shown).

Figure 5. Establishment of splenic B cell compartment by neonatal late transitional B cells.

(A) Surface phenotypes of E17.5 blood (solid line) and splenic (dotted line) B cells. Adult follicular B cells are shown in shaded grey. Gated on CD19+ IgM+ B cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Surface phenotypes of E18.5 and P0.5 splenic B cells. Gated on CD19+ IgM+ B cells, representative of at least 6 independent experiments. (C) Proportions of CD23+ T2 B cells in E18.5 and P0.5 spleen. n=6 for E18, n=8 for P0. (D) Proportions of CD23+ T2 B cells before (input) and after (migrated) Transwell migration assay. (E) Ratios of T1 to T2 B cells in spleen versus blood from E18.5 (white) and P0.5 (shaded) animals, n=3 for each.

To determine the relative abilities of the P0.5 T1 and T2 B cells to specifically migrate in response to CXCL13, we performed a Transwell assay and analyzed input and migrated cells for transitional phenotype (Figure 5D) We observed a 2.3-fold enrichment of CD23+ T2 B cells in the migrated fraction relative to the input, which suggests that chemotactic responsiveness to CXCL13 is acquired by B cells during their maturation from T1 to T2.

Lastly, we compared the surface phenotypes of splenic and blood B cells from each developmental timepoint. At E17.5, the spleen and blood B cell compartments both exclusively contained CD5+ CD9+ B-1a cells (Figure 5A), suggesting that the B cell compartment observed in the spleen at this timepoint is representative of the blood B cell compartment, rather than a uniquely splenic compartment. At E18.5, blood and spleen contained equal proportions of T1 and T2 B cells (Figure 5E). Taken in conjunction with the lack of chemotactic responsiveness to CXCL13 and the random distribution of IgM+ B cells throughout the spleen, these data suggest that the E18.5 splenic B cell compartment is also representative of the blood B cell compartment and not a uniquely splenic compartment. However, at P0.5 the proportion of T2 B cells in the spleen increased significantly relative to blood (Figure 5E). This marks the point at which a uniquely splenic B cell compartment is established, and therefore represents the cellular onset of WP ontogeny. Further, the enhanced migratory capacity of the CD23+ T2 cells along with their overrepresentation in the P0.5 spleen (relative to P0.5 blood as well as to E18.5 spleen) demonstrate that CXCL13-responsive late transitional B cells initiate splenic WP ontogeny.

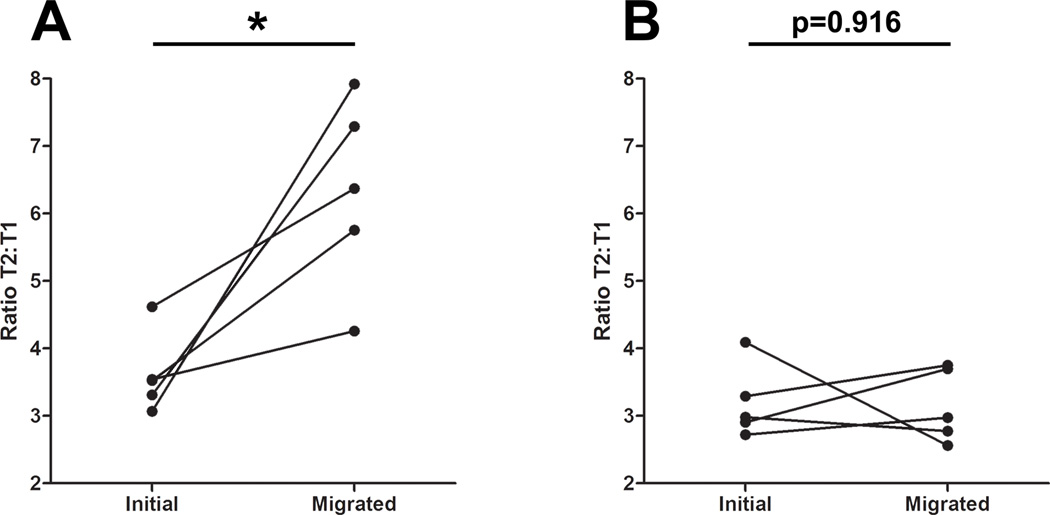

Migratory capacity of adult T1/T2 B cells mirrors that of neonatal B cells

A preponderance of transitional B cells in the neonatal spleen has been reported as early as P3, and these transitional cells give rise to mature B-1a cells (34). As such, we predict that the transitional B cells we observe in the perinatal spleen are also of the B-1 lineage. Developmental differences between transitional B-1 and B-2 cells have been described (35); we therefore sought to determine whether the enhanced chemotactic response of late transitional (relative to early transitional) B cells to CXCL13 is also a characteristic of adult, bone marrow-derived B cells. To address this question, we repeated our Transwell analysis on adult splenic and blood-derived B cells (Figure 6). Consistent with our data from the neonate, we observed a 1.75-fold increase in the ratio of T2 to T1 B cells from peripheral blood after migration toward CXCL13 (relative to input) (Figure 6A), while no difference in the ratio of T2 to T1 B cells was observed after migration of splenic B cells toward CXCL13 (Figure 6B). The similar rates of CXCL13-elicited migration by splenic early and late transitional B cells are likely the result of desensitization to the chemokine; the majority of adult splenic B cells will have encountered CXCL13 upon entry into the WP. The enhanced migratory capacity of blood-derived T2 B cells (relative to T1), however, suggests that acquisition of chemotactic responsiveness to CXCL13 during the maturation from the early to late transitional stages of B cell development is a characteristic of both B-1 and B-2 lineage B cells.

Figure 6. Enhanced CXCL13 responsiveness of adult blood-derived but not spleen-derived T2 B cells.

(A) Ratios of blood-derived T2 to T1 B cells before (input) and after (migrated) specific migration toward 1ug/mL CXCL13 by Transwell migration assay. (B) Ratios of splenic T2 to T1 B cells before (input) and after (migrated) specific migration toward 1ug/mL CXCL13 by Transwell migration assay.

Discussion

These results demonstrate a stepwise and ordered progression of discrete events in the initiation and onset of splenic WP ontogeny: (1) production of CXCL13 protein by perivascular pre-FDC in the late embryonic spleen in an LTα1β2-, TNFα-, and T/B cell-independent manner, which “primes” the spleen for WP ontogeny (7), (2) an increase in peripheral IgM+ B cell numbers, dominated by early transitional B cells, at E18.5, and then at P0.5 (3), the acquisition chemotactic responsiveness to CXCL13 by B cells, (4) aggregation of B cells around the splenic vasculature, and (5) establishment of the first uniquely splenic B cell compartment, defined by an increase in the proportion of late transitional B cells relative to peripheral blood.

The “priming” of the embryonic spleen for WP establishment has been demonstrated by transplantation of E15.5 spleen into the kidney of Rag2/γc−/− mice, and the subsequent establishment of lymphoid architecture surrounding the graft (7). Morever, these “primed” cells have recently been shown to be of a stromal origin (36). Additionally, basal levels of CXCL13 transcription in peripheral lymph node anlagen (presumably stromal cells) have been detected, and shown to be dependent upon neuronally-derived retinoic acid (RA) and the RA receptor β, and that induction of CXCL13 transcription in the intestine can be controlled by stimulation of the Vagus (10th cranial) nerve in a retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 2-dependent manner (37). As the spleen is innervated by the Vagus nerve, it is possible that this or a similar mechanism of CXCL13 regulation controls the initial expression of CXCL13 in the embryonic spleen. How this basal CXCL13 expression (and the consequent induction of SLO ontogeny) is restricted to only a subset of Vagus-innervated organs warrants further investigation.

While initial embryonic expression of CXCL13 is independent of LTα1β2 and TNFα, its upregulation in the spleen, as well as the differentiation and maintenance of splenic FDC, requires physiological concentrations of both. Krautler et al (7) have suggested that the “maintenance of pre-FDC relies on LTβR and their further maturation depends on TNFR1 signaling.” Our observation that perivascular B cell aggregation in the spleen is delayed by 24 hours in the absence of TNFα is in accordance with this prediction, particularly in light of the recent observation that defective WP ontogeny in the absence of LTα1β2 can be rescued by increased concentrations of TNFα (20).

A reduced chemotactic responsiveness of neonatal B cells to CXCL13 has been described (38), but this report demonstrated a gradual acquisition of CXCL13-responsiveness by total B220+ cells (isolated from mesenteric lymph nodes), rather than exclusively IgM+ B cells, between P0 and P4. Our data from the spleen show a near absence of specific migration toward CXCL13 by IgM+ B cells at E18.5, but a frequency of specific migration comparable to that of adult splenic B cells at P0.5. The chemotactic unresponsiveness of the E18.5 B cells, despite their expression of CXCR5 and their ability to mobilize calcium in response to CXCL13 stimulation, suggests that a functional coupling of CXCR5 to cellular chemotaxis is absent in these cells, and the acquisition of CXCL13 responsiveness in the P0.5 cells suggests that this coupling takes place as the transitional cells mature.

CXCR4-mediated chemotaxis toward CXCL12 is dependent up on β-arrestin2 and GRK6 in T cells and, to a lesser extent, B cells (39); the β-arrestin and GRK linking CXCR5 to cellular migration have not yet been identified. Our observation that the B cells from both E18.5 and P0.5 are capable of migration toward CXCL12 – and migrate toward CXCL12 at similar frequencies – demonstrates that cells from both developmental timepoints are capable of chemokine-elicited migration, and suggests the uncoupling of CXCR5 from chemotaxis at the level of the undefined CXCR5-associated GRK/arrestin. This raises an intriguing and novel mechanism for the regulation of chemokine-driven migration in chemokine receptor-expressing cells – differential regulation of GPCR-associated signaling intermediates – and transitional B cells should provide a valuable system in which to elucidate this phenomenon.

Hayakawa and colleagues have reported an intimate, physical association of B-1a cells with WP FDC in the mature, adult spleen (40). Given that the transitional B cells we observe colonizing the P0.5 spleen and initiating WP ontogeny are likely of a B-1 lineage (34), we propose that these cells mature into canonical B-1a cells, and that they continue to support the maintenance of follicular microarchitecture.

The transitional stages of B cell development are commonly described as occurring in the spleen (41,42), but it has been suggested that these stages are, in fact, a blood phenomenon. Our data suggest a compelling refinement of the latter theory: early transitional B cells are effectively excluded from the splenic WP (and are therefore maintained in the blood and/or splenic RP) by their chemotactic unresponsiveness to CXCL13, and only after the window of peripheral tolerance has closed do B cells acquire the ability to migrate toward CXCL13 and are thus allowed egress from the blood/RP and entry into the splenic WP (and other SLO). Teleologically, the lack of chemokine responsiveness by the early transitional B cells affords them the opportunity for tolerance induction to peripheral self antigens not encountered in the fetal liver during their sojourn throughout the body. As such, acquisition of chemotactic responsiveness to CXCL13 represents a discrete step in the maturation of early to late transitional B cells, and we are currently investigating whether susceptibility to BCR-induced tolerance is lost as responsiveness to CXCL13 is acquired. As the differential CXCL13 responsiveness of T2 and T1 B cells is a characteristic of adult bone-marrow derived B cells as well as neonatal, fetal liver-derived B cells, these data have significant implications for the regulation of humoral peripheral tolerance throughout life.

In lower vertebrates such as frog and shark, the mature splenic WP retains the architecture seen early in development, with the B cell zone remaining associated with the central arteriole (5). We plan to determine whether the developmental progression we have uncovered in mice, with CXCL13 expression at the vasculature and CXCR5 responsiveness of developing B cells, extends to all jawed vertebrates. Ultrastructural and some functional data suggest that FDC and germinal centers do not form in lower vertebrates (43), despite the presence all of the basic features of adaptive immunity such as MHC restriction of T cells, and somatic hypermutation and some level of affinity maturation of antibody responses (44). Although LTα and LTβ exist in lower vertebrates (45), these cytokines have not been co-opted for FDC generation and maintenance. Thus, further studies of immune responses in ectotherms may uncover primitive features of immunity that have been overlooked in mammals.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jacqueline Guo for her assistance with immunohistochemistry, as well as Giorgio Trinchieri, Jessica Shiu, Kyle Wilson, Elizabeth Powell, and Peixin Yang both for providing mice and reagents, and for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was funded by NIH R01OD0549.

Harold Neely was a trainee under the Institutional Training Grant T32AI007540 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Abbreviations used in this manuscript

- SLO

secondary lymphoid organ

- RP

red pulp

- WP

white pulp

- MYA

million years ago

- PALS

periarteriolar lymphoid sheath

- LT

lymphotoxin

- FDC

follicular dendritic cell

- LTi

lymphoid tissue inducer.

References

- 1.Boehm T, Hess I, Swann JB. Evolution of lymphoid tissues. Trends in Immunology. 2012;33:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmann J, Greter M, Du Pasquier L, Becher B. B-cells need a proper house, whereas T-cells are happy in a cave: the dependence of lymphocytes on secondary lymphoid tissues during evolution. Trends in Immunology. 2010;31:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mebius RE, Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:606–616. doi: 10.1038/nri1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rumfelt LL, McKinney EC, Taylor E, Flajnik MF. The Development of Primary and Secondary Lymphoid Tissues in the Nurse Shark Ginglymostoma cirratum: B-Cell Zones Precede Dendritic Cell Immigration and T-Cell Zone Formation During Ontogeny of the Spleen. Scand. J. Immunol. 2002;56:130–148. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du Pasquier L, Robert J, Courtet M, Mussman R. B-Cell Development in the Amphibian Xenopus. Immunol. Rev. 2000;175:201–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.2000.imr017501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.den Haan JMM, Kraal G. Innate Immune Functions of Macrophage Subpopulations in the Spleen. J. Innate Immun. 2012;4:437–445. doi: 10.1159/000335216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vondenhoff MFR, Desanti GE, Cupedo T, Bertrand JY, Cumano A, Kraal G, Mebius RE, Golub R. Separation of splenic red and white pulp occurs before birth in a LTαβ-independent manner. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2008;84:152–161. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ansel KM, Ngo VN, Hyman PL, Luther SA, Förster R, Sedgwick JD, Browning JL, Lipp M, Cyster JG. A chemokine-driven positive feedback loop organizes lymphoid follicles. Nature. 2000;406:309–314. doi: 10.1038/35018581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ngo VN, Cornall RJ, Cyster JG. Splenic T zone development is B cell dependent. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:1649–1660. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolte MA, Arens R, Kraus M, van Oers MHJ, Kraal G, van Lier RAW, Mebius RE. B cells are crucial for both development and maintenance of the splenic marginal zone. J. Immunol. 2004;172:3620–3627. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Z. Requirement for RORgamma in Thymocyte Survival and Lymphoid Organ Development. Science. 2000;288:2369–2373. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang N, Guo J, He Y-W. Lymphocyte Accumulation in the Spleen of Retinoic Acid Receptor-Related Orphan Receptor γ-Deficient Mice. J. Immunol. 2003;171:1667–1675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Episkopou V, Kollias G. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF alpha-deficient mice: a critical requirement for TNF alpha in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:1397–1411. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Endres R, Alimzhanov MB, Plitz T, Fütterer A, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Nedospasov SA, Rajewsky K, Pfeffer K. Mature follicular dendritic cell networks depend on expression of lymphotoxin beta receptor by radioresistant stromal cells and of lymphotoxin beta and tumor necrosis factor by B cells. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:159–168. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Wang J, Sun Y, Wu Q, Fu YX. Complementary effects of TNF and lymphotoxin on the formation of germinal center and follicular dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2001;166:330–337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tumanov AV, Grivennikov SI, Kruglov AA, Shebzukhov YV, Koroleva EP, Piao Y, Cui C-Y, Kuprash DV, Nedosapov SA. Cellular Source and Molecular Form of TNF Specify Its Distinct Functions in Organization of Secondary Lymphoid Organs. Blood. 2010;116:3456–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milicevic NM, Klaperski K, Nohroudi K, Milicevic Z, Bieber K, Baraniec B, Blessenohl M, Kalies K, Ware CF, Westermann J. TNF Receptor-1 Is Required for the Formation of Splenic Compartments During Adult, But Not Embryonic Life. J. Immunol. 2011;186:1486–1494. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tumanov AV, Grivennikov SI, Shokhov AN, Rybtsov SA, Koroleva EP, Takeda J, Nedosapov SA, Kuprash DV. Dissecting the Role of Lymphotoxin in Lymphoid Organs by Conditional Targeting. Immunol. Rev. 2003;195:106–116. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto M, Fu Y-X, Molina H, Huang G, Kim J, Thomas DA, Nahm MH, Chaplin DD. Distinct Roles of Lymphotoxin a and the Type I Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Receptor in the Establishment of Follicular Dendritic Cells from Non-Bone Marrow-Derived Cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:1997–2004. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furtado GC, Pacer ME, Bongers G, zech CBENE, He Z, Chen L, Berin MC, Kollias G, o JHCN, Lira SA. TNFα-dependent development of lymphoid tissue in the absence of RORγt+ lymphoid tissue inducer cells. 2013;7:602–614. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruddle NH, Akirav EM. Secondary lymphoid organs: responding to genetic and environmental cues in ontogeny and the immune response. J. Immunol. 2009;183:2205–2212. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van de Pavert SA, Mebius RE. New insights into the development of lymphoid tissues. Nature Publishing Group. 2010;10:664–674. doi: 10.1038/nri2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montecino-Rodriguez E, Dorshkind K. B-1 B Cell Development in the Fetus and Adult. Immunity. 2012;36:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Criscitiello MF, Ohta Y, Saltis M, McKinney EC, Flajnik MF. Evolutionarily conserved TCR binding sites, identification of T cells in primary lymphoid tissues, and surprising trans-rearrangements in nurse shark. J Immunol. 2010;184:6950–6960. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Förster R, Mattis AE, Kremmer E, Wolf E, Brem G, Lipp M. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell. 1996;87:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krautler NJ, Kana V, Kranich J, Tian Y, Perera D, Lemm D, Schwarz P, Armulik A, Browning JL, Tallquist M, Buch T, Oliveira-Martins JB, Zhu C, Hermann M, Wagner U, Brink R, Heikenwalder M, Aguzzi A. Follicular Dendritic Cells Emerge from Ubiquitous Perivascular Precursors. Cell. 2012;150:194–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngo VN, Korner H, Gunn MD, Schmidt KN, Riminton DS, Cooper MD, Browning JL, Sedgwick JD, Cyster JG. Lymphotoxin alpha/beta and tumor necrosis factor are required for stromal cell expression of homing chemokines in B and T cell areas of the spleen. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:403–412. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowman EP, Campbell JJ, Soler D, Dong Z, Manlongat N, Picarella D, Hardy RR, Butcher EC. Developmental Sqitches in Chemokine Response Profiles during B Cell Differentiation and Maturation. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1303–1317. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. β-arrestin-mediated receptor trafficking and signal transduction. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2011;32:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Won W-J, Kearney JF. CD9 is a unique marker for marginal zone B cells, B1 cells, and plasma cells in mice. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5605–5611. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Tung JW, Ghosn EEB, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. Division and differentiation of natural antibody-producing cells in mouse spleen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:4542–4546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allman D, Lindsley RC, DeMuth W, Rudd K, Shinton SA, Hardy RR. Resolution of Three Nonproliferative Immature Splenic B Cell Subsets Reveals Multiple Selection Points During Peripheral B Cell Maturation. J Immunol. 2001;167:6834–6840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cancro MP. Peripheral B-Cell Maturation: The Intersection of Selection and Homeostasis. Immunol. Rev. 2004;197:89–101. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montecino-Rodriguez E, Dorshkind K. Formation of B-1 cells from Neonatal Transitional Cells Exhibits NF-kB Redundancy. J. Immunol. 2011;187:5712–5719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedersen GK, Adori M, Khoenkhoen S, Dosenovic P, Beutler B, Hedestam GBK. B-1a Transitional Cells Are Phenotypically Distinct and Are Lacking in Mice Deficient in IκBNS. PNAS USA. 2014;111:E4119–E4126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415866111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan JKH, Watanabe T. Murine Spleen Tissue Regeneration from Neonatal Spleen Capsule Requires Lymphotoxin Priming of Stromal Cells. J. Immunol. 2014;193:1194–1203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van de Pavert SA, Olivier BJ, Goverse G, Vondenhoff MF, Greuter M, Beke P, Kusser K, Höpken UE, Lipp M, Niederreither K, Blomhoff R, Sitnik K, Agace WW, Randall TD, de Jonge WJ, Mebius RE. Chemokine CXCL13 is essential for lymph node initiation and is induced by retinoic acid and neuronal stimulation. Nature Immunology. 2009;10:1193–1199. doi: 10.1038/ni.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cupedo T, Lund FE, Ngo VN, Randall TD, Jansen W, Greuter MJ, de Waal-Malefyt R, Kraal G, Cyster JG, Mebius RE. Initiation of cellular organization in lymph nodes is regulated by non-B cell-derived signals and is not dependent on CXC chemokine ligand 13. J. Immunol. 2004;173:4889–4896. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fong AM, Premont RT, Richardson RM, Yu Y-RA, Lefkowitz RJ, Patel DD. Defective Lymphocyte Chemotaxis in β-arrestin2- and GRK6-Deficient Mice. PNAS USA. 2002;99:7478–7483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112198299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen L, Shinton SA, Hardy RR, Hayakawa K. Association of B-1 B Cells with Follicular Dendritic Cells in Spleen. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6918–6926. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tussiwand R, Bosco N, Ceredig R, Rolink AG. Tolerance Checkpoints in B-Cell Development: Johnny B Good. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:2317–2324. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pieper K, Grimbacher B, Eibel H. B-Cell Biology and Development. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;131:959–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zapata A, Amemiya CT. Phylogeny of Lower Vertebrates and Their Immunological Structures. In. In: Du Pasquier L, Litman GW, editors. Origin and Evolution of the Vertebrate Immune System. Berlin: Springer; 2000. pp. 67–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flajnik MF. Comparative Analyses of Immunoglobulin Genes: Surprises and Portents. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:688–698. doi: 10.1038/nri889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohta Y, Goetz W, Hossain MZ, Nonaka M, Flajnik MF. Ancestral Organization of the MHC Revealed in the Amphibian Xenopus. J. Immunol. 2006;176:3674–3685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]