Abstract

The determination of accurate binding affinities is critical in drug discovery and development. Several techniques are available for characterizing the binding of small molecules to soluble proteins. The situation is different for integral membrane proteins. Isothermal chemical denaturation (ICD) has been shown to be a valuable biophysical method to determine in a direct and label-free fashion the binding of ligands to soluble proteins. In this communication, the application of isothermal chemical denaturation is applied to an integral membrane protein, the A2a G-protein coupled receptor. Binding affinities for a set of nineteen small molecule agonists/antagonists of the A2aR were determined and found to be in agreement with data from surface plasmon resonance and radioligand binding assays previously reported in the literature. Therefore isothermal chemical denaturation expands the available toolkit of biophysical techniques to characterize and study ligand binding to integral membrane proteins, specifically GPCRs in vitro.

Introduction

G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) drug discovery has historically relied heavily on cell-based, radioligand binding, and displacement assays [1]. Modern biophysical techniques have not been routinely used in GPRC drug discovery process due to the difficulty in generating recombinant forms of membrane proteins that are suitable for these applications. However, recent breakthroughs in GPCR protein engineering have led to the generation of recombinant GPCRs that are now suitable for biophysical methodologies and x-ray crystallography [2, 3]. As a result of the advances in protein engineering and recombinant GPCR production, the crystal structures of more than 26 GPCRs across a broad section of this large complex family have been determined, which has greatly advanced our understanding of structure–function relationship of this important therapeutic target. The availability of high quality and sufficient quantities of stable recombinant GPCRs has also enabled the biophysical characterization of GPCRs and their interaction with ligands [4, 5].

Ligand binding to GPCRs can be characterized using different biophysical methods including calorimetry, and surface plasmon resonance, which rely on measuring a physical observable (heat, fluorescence, molecular weight, etc...) that discriminates between free and bound states of the protein [6, 7]. Another approach is to measure the ligand induced shift in thermal denaturation; however, this technique does not provide actual binding affinities at room temperature without previous knowledge of denaturation and binding enthalpies [8]. An alternative approach is to measure the ligand effects on protein stability using chemical denaturation, which can be implemented at any temperature [9, 10]. It has been shown before that ligand induced changes in chemical denaturation allow accurate determination of binding affinities with a surprisingly wide dynamic range (high micromolar to sub nanomolar) and in situations where binding changes the cooperativity of the unfolding transition or refolds intrinsically disordered domains [10].

In this work, isothermal chemical denaturation (ICD) was applied as a novel tool to characterize ligand binding to recombinant GPCRs. ICD measurements and ligand binding affinities were obtained in a direct and label free fashion using a detergent solubilized engineered form of the therapeutically relevant adenosine A2 receptor (A2a-8M) with enhanced thermostability. This engineered receptor has been well characterized by us and others [11, 12] thus allowing meaningful comparison of results obtained by ICD and other biophysical techniques.

The new understanding of structure–function relationship gained from the crystal structures and the characterization of the GPCR-ligand interactions from biophysical techniques, like ICD, now appear to be able to guide drug design and open up routes to rationally develop ortho- and allosteric modulators of GPCRs. Together, these methods are presently on the cusp of revolutionizing the GPCR drug discovery processes [13].

Materials and Methods

Reagents and instrumentation

Compounds were purchased from Sigma (sigmaaldrich.com) and Tocris (tocris.com), and dissolved in DMSO to 100mM before diluting to their respective concentrations in specific reactions buffers below. Detergents were purchased from Anatrace, sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide (sulfo-NHS) from BioRad (biorad.com) and1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminpropyl)-carbodiimde hydrochloride (EDC) from GE Healthcare Bio-Science AB (biacore.com).

Receptor production

DNA for A2a-8M (pdb code 3UZA) was synthesized (Genewiz) and cloned into pFASTbac1 using BamHI and Xba1 restriction sites and expressed using baculovirus mediated insect expression following protocols previously described [14]. Following membrane isolation and solubilization, the protein was purified and eluted from Talon resin with 25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 350 mM NaCl, 0.3 % DDM, 4 mM theophylline, 200 mM Imidazole and concentrated to 4.3 mg/mL. SDS-PAGE showed a protein purity of ~90 %.

Isothermal chemical denaturation

The binding affinities (Kd) of the test compounds to the A2a-8M receptor were determined by measuring ligand induced shifts in protein stability. Protein stability was determined at 25°C by chemical denaturation using guanidinium hydrochloride (GuHCl). Experiments were performed with an AVIA Isothermal Chemical Denaturation 2304 system (AVIA Inc, Norton MA). This instrument automatically prepares and measures all samples starting from stock buffer, urea and protein solutions. 24 point linear gradients from 0 – 6 M GuHCl were autogenerated from the formulation buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 350 mM NaCl, 0.05% (w/v) n-Dodecyl -D-maltoside (DDM), 3.0% (v/v) DMSO) and the denaturant buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 350 mM NaCl, 0.05% (w/v) n-Dodecyl -D-maltoside (DDM), 3.0% (v/v) DMSO, 6 M GuHCl). Protein at 2.33 μM in formulation buffer was added into the auto-generated 24 point linear GuHCl gradients, resulting in a final protein concentration of 0.167 μM. For samples containing ligand, protein was added to ligand stock, with ligand being present at 5.6, 28 or 300 μM, depending on the expected binding strength. Final ligand concentrations after dilution were 0.4, 2 or 21.4 μM.

In all cases, intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence was used to monitor denaturation. The excitation wavelength was 280 nm and scans of the emission intensity were recorded between 300 and 500 nm. The denaturant concentration dependence of the fluorescence intensity at 338 nm or 316 nm was analyzed in terms of standard equations for chemical denaturation analysis as described in the Results Section [15, 16].

SPR analysis of small molecule binding to receptors

Studies were performed at 25°C using a Biacore T200 using NTA (carboxymethylated dextran pre-immobilized with nitrilotriacetic acid) sensor chips (preconditioned with a one-minute pulses of 350 mM EDTA pH 7.0, and charged for 1 min with 500 uM Ni2+ H2O) and equilibrated with running buffer. For capture-coupling of A2a-8M, a flow cell surface was activated for five minutes (at 10 uL/min) with a 1:1 mixture of 0.1 M sulfo-NHS:0.4 M EDAC in 500 mM MES pH 5.3 prior to injection of the receptor; A2a-8M were diluted 200X in running buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 350 mM NaCl, 0.05 % (w/v) DDM, 2 % (v/v) DMSO) and injected at 5 uL/min to achieve capture levels of 5,000 resonance units (RU). The captured-coupled receptor surfaces were washed with running buffer for >2 hours before ligand injections.

For kinetic characterization of small molecule binding to A2a-8M and A2a-BRIL, agonists, antagonists and control compounds (MW range 180-523 Da; Kd range for antagonists 2 nM-8 μM) were each tested in 7 point dose response runs for binding to A2a-8M (three-fold dilution series from 1.0 μM to 1.4 nM for high affinity ligands with Kds < 1 μM and 10.0 μM to 14 nM for the remaining compounds, respectively). All samples were injected at a flow rate of 30 μL/min.

Data processing and analysis of SPR data was performed using Biacore T200 Evaluation software Version 2.0. For kinetic analysis, data were double reference and globally fit to a 1:1 interaction model including a term for mass transport to obtain binding parameters. For equilibrium analysis, the responses at equilibrium were plotted against analyte concentration and fit to a simple 1:1 binding model.

Results and Discussion

Chemical Denaturation of A2a-8M

The feasibility of triggering and studying the chemical denaturation of the thermally stabilized adenosine A2 G-protein coupled receptor (A2a-8M) by measuring changes in its intrinsic fluorescence emission spectrum is shown in Figure 1 (left panel). In this figure, the fluorescence emission spectra in the absence and in the presence of 5.5M GuHCl are shown. The maximum is observed near 338nm. There is an almost five-fold decrease in intensity at the highest GuHCl concentration. Furthermore, the decrease follows the characteristic sigmoidal shape associated with a folding/unfolding transition. In the right panel of Figure 1, the fluorescence intensity at 338nm has been plotted as a function of denaturant concentration. The denaturation transition is evident and characterized by a midpoint close to 3M GuHCl. In the figure, the red and green straight lines correspond to the characteristic values of the native and denatured states respectively. Since the transition shows a single inflection, the data in the figure can be analyzed by non-linear least squares in terms of the two state transition equation [10]:

| (1) |

Where yn and yd are the native and denatured baselines which are considered to be straight lines, R the gas constant, T the absolute temperature and ΔG the Gibbs energy of protein stability which is a linear function of the denaturant concentration [15, 16].

Figure 1.

Left Panel: Fluorescence emission spectra of A2a-8M using an excitation wavelength of 280 nm. A2a-8M spectra were obtained in the absence (squares) and in the presence (circles) of 5.5 M GuHCl. There is an almost five-fold decrease in intensity at the highest GuHCl concentration. Right Panel: Fluorescence emission of A2a-8M at 338 nm using an excitation wavelength of 280 nm from 0 to 5.5M GuHCl increased as a linear gradient (squares). The red and green solid lines represent the native and denatured states baselines. The solid line is the calculated curve with the best parameters from non-linear least squares fit for a two state transition model (ΔG = 3.96 kcal/mol and m = 1.37 kcal/mol×M).

Since the native state is taken as reference, ΔG is positive when the native state of the protein is stable. The larger the magnitude of ΔG the higher the stability of the native state. ΔG is zero at the denaturation midpoint and becomes negative when the protein is denatured.

| (2) |

Analysis of the denaturation curve yields ΔG0 and m. ΔG0 is the Gibbs energy in the experimental solvent at zero denaturant concentration and m is the rate of change of the Gibbs energy with respect to the denaturant concentration [15, 16]. The two state equation accounts well for the data; the solid line in the right panel of Figure 1 is the calculated curve with the best parameters from the fit: ΔG = 3.96 kcal/mol and m = 1.37 kcal/mol×M. The midpoint of the denaturation curve C1/2 is equal to ΔG/m which in this case amounts to 2.9 M GuHCl.

Chemical Denaturation of A2a-8M in the Presence of Ligands

Ligand binding perturbs the conformational equilibrium of a protein in a very specific way. A ligand that binds to the native state will affect the Gibbs energy according to the following equation [10]:

| (3) |

Where n is the binding stoichiometry. It is evident that the Gibbs energy will increase in magnitude in a manner that depends on the concentration of ligand ([L]) and its binding affinity (Kd). In fact, knowledge of the Gibbs energy in the absence of ligand (ΔGo), the Gibbs energy in the presence of a given ligand concentration () and the ligand concentration ([L]) allows calculation of the binding affinity. [L] is the free ligand concentration while the concentration that is known experimentally is the total concentration (free ligand plus bound ligand) ([LT]). If the total ligand concentration is much larger than the protein concentration, then the free and total ligand concentrations are comparable. However, if the protein concentration is similar or larger than the total ligand concentration, the free and total ligand concentration are not equal in magnitude and the use of the total concentration in equation 3 will give an erroneous result. Fortunately, exact equations that allow for calculation of the free ligand concentration if the protein concentration ([PT]) is known have been derived [10, 17]:

| (4) |

Equations 3 and 4 allows calculation of the binding affinity as described in [10].

In drug design, promiscuous compounds that bind nonspecifically to the denatured state are often observed. In general, if a compound also binds to the denatured state, equation 3 will contain an additional term that accounts for denatured state binding. It must be noted that this term is preceded by a negative sign indicating that binding to the denatured state will destabilize the native state.

| (5) |

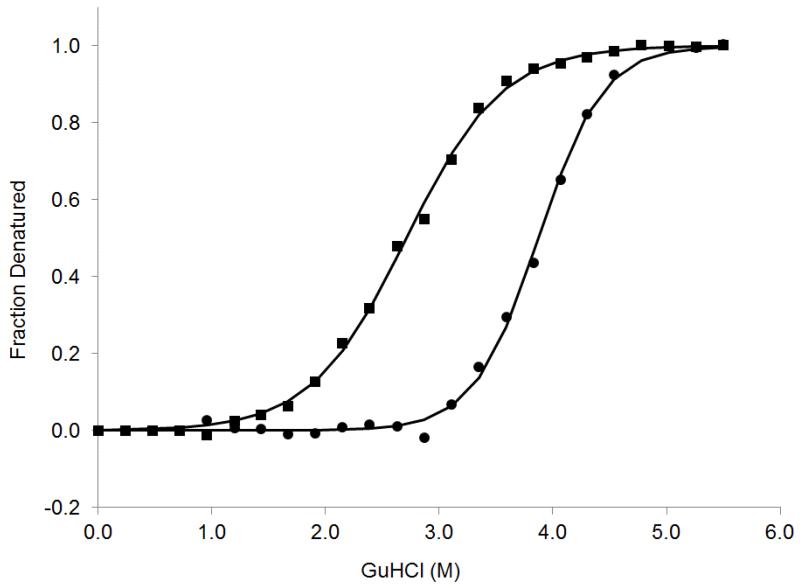

Figure 2 illustrates the effect of ligand binding on the stability of the A2a-8M G-protein coupled receptor. In this figure the denaturation curves obtained in the absence and in the presence of 2μM of the antagonist ZM241385 are shown. Since the A2a-8M preparations contained a residual 0.5 μM concentration of the ligand theophiline which binds with a Kd of 1.6μM and competes for the same binding site, all measured Kd’s reported here were corrected by the standard equation Kd = Kd,app×(1 + [Theophiline]/Kd,theo) = Kd,app×1.31. The stabilizing effect is apparent in the shift of the denaturation curve to higher denaturant concentrations (C1/2 increases from 2.9 to 3.8 M GuHCl). Analysis of the denaturation curves indicates that G increases from 3.96 to 8.0 kcal/mol which results in a Kd of 2nM. This is in excellent agreement with the SPR Kd value of 1.8 nM (Figure 3) reported here, and as well as those measured by others [11, 18, 19].

Figure 2.

GuHCl induced denaturation of A2A-8M in the absence (squares) and presence of 2 μM ZM241385 (circles). In all cases the protein concentration was 0.167 μM. Denaturation curves were obtained by measuring the fluorescence intensity at 338 nm. In this figure, the normalized curves have been plotted as a function of the concentration of denaturant. A significant increase in protein stability is observed in the presence of the ligand as evidenced by the shift in C1/2 to higher denaturant concentrations. Analysis of the data yielded a Kd of 2.0nM in perfect agreement with the one obtained by SPR. All the thermodynamic data is summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Representative results from surface plasmon resonance experiments. A2a-8M was captured on a NTA chip via its His tag and subsequently amine coupled to the chip surface.Ligand binding to A2a-8M is shown for ZM241385 at concentrations of 111, 37 12.3, 4.1, 1.4 nM, respectively. On and off rates were used to calculate the Kd (1.8 nM). All the SPR data is summarized in Table 1.

To rigorously test chemical denaturation of A2a-8M in the presence of ligands as a way to determine Kd’s for GPCR ligands, we measured nineteen small molecular weight compounds with molecular weights between 232 and 535 Da (The chemical structures of the compounds are shown in the Supplementary Figure). Thirteen of the nineteen ligands are bona fide agonists or antagonists of the WT A2a receptor covering a wide range of binding affinities ranging from 50 pm for SCH442416 [20] to > 10 uM for CGS21680 [18]. The remaining six ligands are known to bind to either one of the 2, A3a and CXCR4 receptors but have no known affinity to the WT A2a receptor. The latter six ligands therefore served as control compounds for our experiments. Table 1 summarizes the results for all compounds considered in these studies.

Table 1.

Dissociation constants (Kd) from isothermal chemical denaturation experiments for A2a-8M receptor binding to a set of compounds.

| [L]2 (μ-M) |

ΔG | m | C½ | ICD Kd (nM) |

SPR Kd (nM) |

Literature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apo (338 nm) | 3.96 | 1.37 | 2.90 | |||||

| Apo (316 nm) | 3.93 | 1.37 | 2.88 | |||||

| Test Compounds | ||||||||

| SCH442416 1) | Antagonist | 0.4 | 6.54 | 1.67 | 3.92 | 3.0 | 7.9 | |

| TC-G1004 | Antagonist | 0.4 | 4.94 | 1.42 | 3.49 | 62 | 48 | |

| ZM241385 | Antagonist | 2 | 8.03 | 2.11 | 3.82 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 23) ; 2.54) |

| SCH58261 1) | Antagonist | 2 | 7.01 | 1.80 | 3.91 | 11 | 14 | 1.3 3); 3.84) |

| PSB1115 | Antagonist | 2 | 6.22 | 1.63 | 3.82 | 43 | 48 | |

| Istradefyllin | Antagonist | 2 | 6.44 | 1.77 | 3.64 | 30 | 70 | 424) |

| LUF5834 | Partial Agonist |

2 | 6.03 | 1.90 | 3.18 | 59 | 46 | |

| Caffeine | Antagonist | 2 | 4.05 | 1.24 | 3.28 | 14100 | 1220 | 64564) |

| PSB0777 | Agonist | 21 | 3.47 | 1.56 | 2.22 | no binding | no binding |

|

| ANR94 | Antagonist | 21 | 5.82 | 1.65 | 3.53 | 960 | 141 | |

| Adenosine | Agonist | 21 | 3.77 | 1.17 | 3.21 | no binding | no binding |

|

| Theophylline | Antagonist | 21 | 3.89 | 1.28 | 3.03 | no binding | 1600 | 631 3) ; 43654) |

| CGS21680 | Agonist | 21 | 5.65 | 1.73 | 3.27 | 1400 | 8000 | > 10000 3) |

| Control Compounds | ||||||||

| WZ811 | 2 | 3.53 | 1.19 | 2.98 | no binding | no data | ||

| ZK756326 | 21 | 5.11 | 1.50 | 3.41 | 3700 | no data | ||

| Hemado (agonist) | 21 | 4.59 | 1.77 | 2.59 | 11600 | no binding |

||

| SKF86466 HCl | 21 | 3.38 | 1.55 | 2.18 | no binding | no data | ||

| Guanfacine HCl | 21 | 3.08 | 1.37 | 2.25 | no binding | no data | ||

| MRS1334 | 2 | 4.15 | 1.30 | 3.20 | 5500 | 5900 |

Analyzed at 316 nm to eliminate fluorescence interference.

High affinity compounds were measured at [L] = 2 μM except when fluorescence from the compound interfere with the measurement. In those cases [L] = 0.4μM was used. Low affinity compounds were measured at [L] = 21 μM except when low solubility (caffeine, MRS1334) or fluorescence interference (WZ811) precluded this concentration

Robertson et al [18]

Bennett et al [19]

SPR Measurements

SPR was used to measure compound binding to A2a-8M in order to allow comparison of our chemical denaturation results with data from an independent direct ligand binding technique that uses the same protein. For SPR studies the A2A–8M was first captured via its His tag at a density of ~ 5000 RU on a NTA chip and subsequently coupled by cross linking the dextran surface of the chip with free lysine residues of the receptor. Ligand binding induced responses indicated that ~ 80% of coupled receptors could be engaged in small molecule binding. For high affinity compounds Kd’s were derived from kinetic analysis, exemplified for ZM241384 in Figure 3. For compounds with Kd’s > 0.5 μM, the Kd’s were derived from equilibrium binding analysis (Table 1). SPR experiments were conducted at 25°C and Kd’s of 1.8, 14 and 48 nM were determined for the compounds ZM241385, SCH58261 and PSB1115, respectively (Table 1). These values are also in agreement with an SPR study performed at 10°C in which Kd’s of 2, 10 and 158 nM were measured for the same three ligands [18].

Comparison of ICD and SPR Determined Binding Affinities

The agreement between the Kd values obtained by ICD and SPR is especially good for the high affinity antagonists as shown in Figure 4. In this figure, the ICD and SPR determined Kd values for compounds with affinities stronger than 100 nM have been plotted against each other, yielding a correlation coefficient of 1.04. For compounds with affinities in the mid-micromolar range the agreement is good but quantitatively not as close-fitting as for the high affinity compounds. In general, measurement of the binding affinity of weak binders necessarily requires higher concentrations of the compounds. Some of those compounds couldn’t be measured at higher concentration due to solubility or optical interference. Finally, for some compounds no binding was detected; either no changes were detected or even a decrease in protein stability was observed. A decrease in protein stability is usually observed when the compound binds non-specifically to the denatured state as described by equation 5.

Figure 4.

Correlation between Kd values (nM units) determined by chemical denaturation and surface plasmon resonance. The coefficient for the logarithmic plot was obtained by linear least squares forcing the intercept to zero. If the intercept is allowed to float it is equal to 0.25 and the slope 0.87. Ligands in the graph are SCH442416, TC-G1004, ZM241385, SCH58261, PSB1115, Istradefyllin, LUF5834.

Summary

Using ICD, the binding affinities for a set of nineteen agonist/antagonist small molecules of the A2aR were measured and found to be in strong agreement with data from SPR and radio ligand binding assays previously reported in the literature. The agreement was best for the high affinity compounds. This is not surprising, since Kd determination by ICD relies significantly in the shift of the midpoint of the protein denaturation curve to higher denaturant concentrations. High affinity ligands induce large shifts at relatively low concentrations. On the other hand, low affinity ligands require concentrations that sometimes approach their solubility limit in order to elicit similar effects. In general, affinity determination of weak compounds by ICD is limited by their solubility. As a rule of thumb, a ligand concentration at least two orders of magnitude higher than Kd yields optimal results. The studies presented here indicate that ICD expands the available toolkit of biophysical techniques that can be used to characterize and study ligand binding to GPRCs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health GM056550 (E.F.) and GM096751 (R.K.B) and from the National Science Foundation MCB-1157506 (E.F.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Zhang R, Xie X. Tools for GPCR drug discovery. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2012;33:372–384. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Standfuss J, Edwards PC, D’Antona A, Fransen M, Xie G, Oprian DD, Schertler GFX. Crystal structure of constitutively active rhodopsin: How an agonist can activate its GPCR. Nature. 2011;471:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature09795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chun E, Thompson AA, Liu W, Roth CB, Griffith MT, Katritch V, Kunken J, Xu F, Cherezov V, Hanson MA, Stevens RC. Fusion partner toolchest for the stabilization and crystallization of G protein-coupled receptors. Structure. 2012;6:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Navratilova I, Dioszegi M, Myszka DG. Analyzing ligand and small molecule binding activity of solubilized GPCRs using biosensor technology. Anal Biochem. 2006;355:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Katritch V, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Diversity and modularity of G protein-coupled receptor structures. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Langelaan DN, Ngweniform P, Rainey JK. Biophysical characterization of G-protein coupled receptor-peptide ligand binding. Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;89:98–105. doi: 10.1139/o10-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fang Y, Frutos AG, Verklereen R. Label-Free Cell-Based Assays for GPCR Screening. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening. 2008;11:357–369. doi: 10.2174/138620708784534789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Matulis D, Kranz JK, Salemme FR, Todd MJ. Thermodynamic stability of carbonic anhydrase: Measurements of binding affinity and stoichiometry using thermofluor. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5258–5266. doi: 10.1021/bi048135v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mahendrarajah K, Dalby PA, Wilkinson B, Jackson SE, Main ERG. A high-throughput fluorescence chemical denaturation assay as a general screen for protein-ligand binding. Anal Biochem. 2011;411:155–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schon A, Brown RK, Hutchins B, Freire E. Ligand binding analysis and screening by chemical denaturation shift. Analytical Biochem. 2013;443:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhukov A, Andrews SP, Errey JC, Robertson N, Tehan B, Mason JS, Marshall FH, Weir M, Congreve M. Biophysical mapping of the adenosine A2A receptor. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;54:4312–4323. doi: 10.1021/jm2003798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rich RL, Errey J, Marshall F, Myszka DG. Biacore analysis with stabilized GPCRs. Analytic Biochemistry. 2011;409:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shoichet BK, Kobilka BK. Structure-based drug screening for G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Congreve M, Andrews SP, Dore AS, Hollenstein K, Hurrell E, Langmead CJ, Mason JS, Ng IW, Tehan B, Zhukov A, Weir M, Marshall FH. Discovery of 1,2,4-Triazine Derivatives as Adenosine A2A Antagonists using Structure Based Drug Design. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;55:1898–1903. doi: 10.1021/jm201376w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bolen DW, Santoro MM. Unfolding free energy changes determined by the linear extrapolation method. 2. Incorporation of dGn-u values in a thermodynamic cycle. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8069–8074. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Santoro MM, Bolen DW. Unfolding free energy changes determined by the linear extrapolation method. 1. Unfolding of phenylmethanesulfonyl.alpha.chymotrypsin using different denaturants. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8063–8068. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Freire E, Mayorga OL, Straume M. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry. Anal. Chem. 1990;62:950A–959A. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Robertson N, Jazayeri A, Errey J, Baig A, Hurrell E, Zhukov A, Langmead CJ, Weir M, Marshall FH. The properties of thermostabilised G protein-coupled receptors (StaRs) and their use in drug discovery. Neuropharmacy. 2011;60:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bennett KA, Tehan B, Lebon G, Tate CG, Weir M, Marshall FH, Langmead CJ. Pharmacology and Structure of Isolated Conformations of the Adenosine A2A Receptor Define Ligand Efficacy. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83:949–958. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.084509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Todde S, Moresco RM, Simonelli P, Baraldi PG, Cacciari B, Spalluto G, Varani K, Monopoli A, Matarrese M, Carpinelli A, Magni F, Kienle MG, Ferrucio F. Design, Radiosynthesis, and Biodistribution of a New Potent and Selective Ligand for in Vivo Imaging of the Adenosine A2A Receptor System Using Positron Emission Tomography. J Med Chem. 2000;43:4359–4362. doi: 10.1021/jm0009843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.