Abstract

Neural crest cells emerge from the dorsal neural tube early in development and give rise to sensory and sympathetic ganglia, adrenal cells, teeth, melanocytes and especially enteric nervous system. Several inhibitory molecules have been shown to play important roles in neural crest migration, among them are the chemorepulsive Slit1–3. It was known that Slits chemorepellants are expressed at the entry to the gut, and thus could play a role in the differential ability of vagal but not trunk neural crest cells to invade the gut and form enteric ganglia. Especially since trunk neural crest cells express Robo receptor while vagal do not. Thus although we know that Robo mediates migration along the dorsal pathway in neural crest cells, we do not know if it is responsible in preventing their entry into the gut. The goal of this study was to further corroborate a role for Slit molecules in keeping trunk neural crest cells away from the gut. We observed that when we silenced Robo receptor in trunk neural crest, the sympathoadrenal (somites 18–24) were capable of invading gut mesenchyme in larger proportion than more rostral counterparts. The more rostral trunk neural crest tended not to migrate beyond the ventral aorta, suggesting that there are other repulsive molecules keeping them away from the gut. Interestingly, we also found that when we silenced Robo in sacral neural crest they did not wait for the arrival of vagal crest but entered the gut and migrated rostrally, suggesting that Slit molecules are the ones responsible for keeping them waiting at the hindgut mesenchyme. These combined results confirm that Slit molecules are responsible for keeping the timeliness of colonization of the gut by neural crest cells.

Keywords: neural crest, cell migration, enteric nervous system, Robo

Introduction

The neural crest is a group of cells that emerge early in development from the dorsal neural tube and migrate along pathways that are characteristic of their axial level of origin (Bronner-Fraser et al., 1991; Le Douarin et al., 1992). Neural crest cells give rise to a good portion of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) formation, cranio-facial structures and even endocrine organs. Probably the most intrinsic and characteristic feature of these cells is their precise migratory pathways along their rostro-caudal axis (Gammill and Roffers-Agarwal, 2010; Theveneau and Mayor, 2012). One of its classic pathways is that of vagal neural crest cells. These vagal neural crest cells emerge from the caudal hindbrain (between somites 1–7) and migrate into the developing gut where they extensively divide and eventually differentiate into the enteric nervous system (ENS) cells (Burns et al., 2002; Kuo and Erickson, 2010, 2011). In contrast, trunk neural crest cells (those arising from 8–25 somite levels) never enter the gut (Erickson and Goins, 2000b; Le Douarin and Teillet, 1974b).

Many inhibitory molecules have been shown to play critical roles in determining neural crest migration patterns, especially, ephrinB family members (Krull et al., 1997) and Semaphorins (Eickholt et al., 1999; Gammill et al., 2006). However, none of these molecules was able to explain the differences between the ability of vagal and trunk neural crest populations to enter the gut. A clue came from finding that only migrating trunk neural crest cells expressed Slit Robo receptors (De Bellard et al., 2003). Slit proteins are not only well known chemorepellants for axons and neuronal migration (Brose et al., 1999; Kidd et al., 1999; Kinrade et al., 2001; Zhu et al., 1999) but in addition they are powerful repellents of trunk neural crest cells (De Bellard et al., 2003).

Seminal work from the labs of Le Douarin and Erickson showed that trunk crest cells transplanted to the vagal position could enter the gut, albeit never to the extent of vagal crest (Burns et al., 2002; Le Douarin and Teillet, 1974a; Le Douarin and Teillet, 1973). These findings showed that trunk crest cells will not enter the developing gut, not that they are incapable of doing so. The key to their poor colonization came from studies by Newgreen and Burns labs which showed that the trunk cells failed to match vagal crest cells in proliferation once in the intestinal tissue, (Newgreen et al., 1980; Zhang et al., 2010) due to lack of ret receptor (Delalande et al., 2008). In addition, Burns and colleagues showed that the enteric neural crest shows cell autonomous differences in their migratory properties, with the vagal neural crest being more invasive of the gut than the caudal, sacral crest population. The reasons for this difference in invasive capacity between vagal and sacral crest has yet to be determined (Burns, 2005).

Here we further examined and settled the potential role of Slit molecules in keeping trunk neural crest cells from entering the gut. Slits are expressed near the entrance to the gut during trunk migration but not during vagal migration, while trunk and sacral neural crest express Robo receptors. We tested the hypothesis of a functional role for Slits in keeping trunk neural crest from migrating into and populating the gut by loss-of-function experiments via electroporation of a dominant negative Robo receptor. The results show for the first time that trunk and sacral neural crest cells can enter the gut if Robo receptors are silenced, thus giving account for the differential ability of vagal but not trunk neural crest cells to invade and innervate the gut. Interestingly, we also found axial differences in the invading capabilities into the gut between more rostral trunk versus sympathoadrenal trunk (somites 18–24), suggesting the presence of another repellant for trunk neural crest cells in the gut.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animals

Chicken embryos were obtained by incubating fertilized chicken eggs at 38°C as described by Hamburger and Hamilton (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951) until desired stage of development.

Mouse strains

All animals were generated in a mixed CD-1/129Sv/C57Bl6 background. Robo mutants were obtained by crossing mice with Robo1 and Robo2 mutant alleles already linked (Ma and Tesseier-Lavigne, 2007). Slit mutants were obtained by crossing Slit1−/−;Slit2+/−;Slit3+/− animals (Plump et al., 2002; Yuan et al., 2003). PCR based genotyping was done following previously described protocols (Grieshammer et al., 2004; Plump et al., 2002; Sabatier et al., 2004; Yuan et al., 2003).

2.2 In situ hybridization

Chicken embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight before being stored in 0.1 M Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS). Patterns of gene expression were determined by whole-mount in situ hybridization using DIG-labeled RNA antisense probes as described in Grove’s lab website (http://www.bcmneuroscience.org/groveslab/protocols.php). The cSlit1, cSlit2, cRobo1 and mSox10 probes used are described in (De Bellard et al., 2003).

2.2 Electroporations of chicken neural tubes

Chicken embryos windowed and visualized with India ink (10% in Ringer’s solution) to determine their stage of development. After gently removing covering membrane, 1–2mg/ml solution of DNA (pMES-GFP, pCax-RoboD2) was injected into the embryos neural tubes using a mouth pipette and immediately electroporated with two 50 ms pulses of 20 mV each. Embryos were sealed with tape and re-incubated for 24 hrs. until fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde.

2.3 Whole mount immunofluorescence

After overnight incubation in blocking buffer (PBS with 1% Triton-X100, 10% goat serum), electroporated embryos were incubated with DAPI to visualize nuclei and photographed using Zeiss A-1 AxioImager.

3. Results

3.1 Distribution of Slit and Robo molecules in the developing chicken embryo

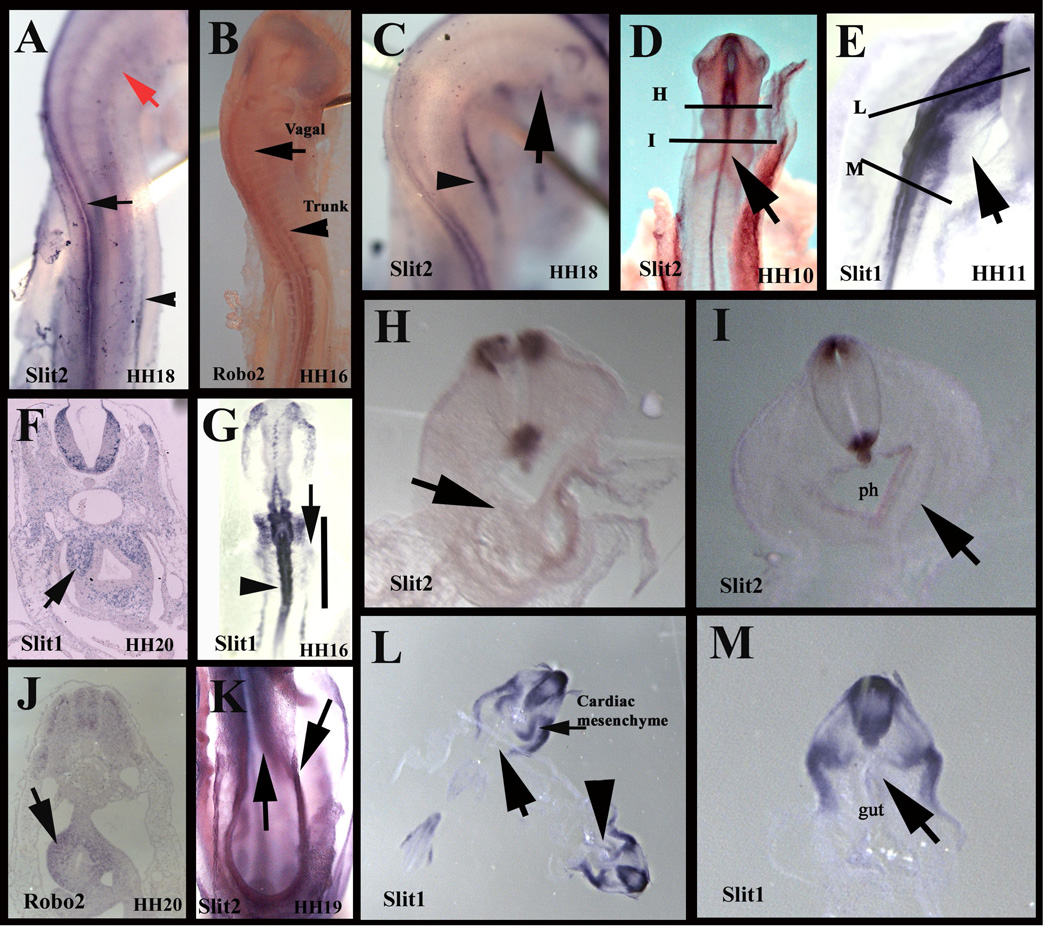

Slit molecules became known as chemorepellants expressed along the pathways of growing axons (Kidd et al., 1999). But in addition to axonal pathfinding, Slit molecules are also expressed along neural crest migration pathways (De Bellard et al., 2003; Jia et al., 2005; Shiau et al., 2008). One which holds special relevance is its expression along the developing gut (De Bellard et al., 2003). Here we revised this past data and looked at younger stages to do a more extensive analysis. We found that Slit molecules expression in the gut mesentery begins truly past vagal migration levels (Fig.1). Slit2 and Robo2 in situ hybridization of HH16–19 chicken embryos, during the peak of trunk neural crest migration, shows that Slit2 is expressed along the primordial gut folds in the trunk (Fig.1A, C, K), while migrating trunk shows Robo2 expression in trunk, not vagal neural crest cells (Fig.1B) (De Bellard et al., 2003). At later stages, HH20, we found that Slit1 expression remained strong in the gut (Fig.1F), and interestingly, we also found that Robo2 expression is quite strong in the gut, implying that it is up-regulated in enteric neural crest cells after they reach and cross Slit expressing gut mesentery tissues (Fig.1J) (Long et al., 2004).

Figure 1. Slit and Robo expression in chicken embryos.

Whole mount and sections of in situ hybridization for Slit and Robo in HH16–20 in chicken embryos. A Slit2 is expressed in dorsal neural tube (arrow), mesonephros (arrowhead) and not in vagal region (red arrow) in HH18 embryo. B Robo2 receptor is expressed in migrating trunk neural crest (arrowhead) but not in vagal (arrow). C Slit2 is not expressed in the ventral region at vagal level (arrow), although it is expressed in gut region posterior to the heart (arrowhead) at HH18. D Slit2 is expressed in dorsal neural tube (arrow) in HH10 with lines for sections shown in H and I. E Slit1 embryo at HH11 with lines for sections shown in L and M arrow points to pharynx. F sections in hindbrain region showing Slit1 expression in gut (arrow) of a HH20 embryo. G whole mount for Slit1 showing expression in dorsal neural tube (arrowhead) and absence where the gut is beginning to develop (arrow and line point to primordial gut mesenchyme). H, I sections of Slit2 embryo in D showing lack of Slit2 expression in pharynx region. J section at sacral level showing Robo2 expression of cells in gut (arrow) at HH20. K ventral side of HH19 embryo showing expression of Slit2 along gut mesenchyme (arrows) L, M sections of Slit1 embryo in E showing lack of Slit1 expression in pharynx region (arrows) Arrowhead corresponds to section on M at higher magnification.

We also looked at Slits expression in HH10–11, during the peak of vagal neural crest migration. We found that Slit2 is expressed in the developing pharynx epithelia, but not in the surrounding mesenchyme through which vagal crest cells migrate (Fig.1D, H, I). Similarly, Slit1 expression was not observed in pharynx mesenchyme, albeit it was in the cardiac mesoderm primordia (Fig.1G, L, M).

3.2 Silencing Robo receptor in trunk neural crest cells them to enter and populate the developing gut

If Slit/Robo interactions are crucial for the difference between vagal and trunk neural crest migratory capabilities into the gut, one would think that expressing Robo in vagal crest would prevent them from entering/populating the gut. However, when we did these electroporations in vagal or trunk neural crest there was practically no delamination from the neural tube (Giovannone et al., 2012).

There are several ways to knockout a signal: by mutating/knocking out its receptor, by RNAi/shRNA or by silencing the receptor by co-expression of a dominant negative form. This last one is powerful and simple in chicken embryos since we can control the timing, area of expression and follow specific cells apart from normal cells. Here, we performed a set of loss-of-function (LOF) experiments in chicken embryos using a dominant negative form of Robo2 receptor in order to silence it in specifically in trunk neural crest cells (Hammond et al., 2005). Chicken embryos from HH14–18 were electroporated along the trunk neural tube with control GFP or a dominant negative form of Robo2 (RD2, missing the cytoplasmic domain). After 24hrs of incubation we look for presence or absence of migrated GFP cells in the developing gut in the Robo LOF embryos and compared with control GFP vector.

Table I summarizes our electroporations and findings. The first observation was that the younger the embryos the fewer the RD2 cells in the gut mesentery along the trunk region. Analogously to the work done by Erickson and Goins (Erickson and Goins, 2000b) we divided the area into A and B in order to quantify the embryos that showed cells past the lateral region of dorsal aorta. A corresponds to ventral aorta and B gut mesenchyme or developing gut. As could be observed, HH14 had only two embryos with cells in area expressing Slit compared with HH16 sympathoadrenal or even more, HH17 sacral crest.

Table I summarizes our electroporations and findings.

We divided the area covered by neural crest cells into A and B in order to quantify the embryos that showed cells past the lateral region of dorsal aorta (A). A corresponds to ventral aorta and B gut mesenchyme or developing gut.

| HH14 | HH14 | HH16 | HH16 | HH17 | HH17 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFP | RD2 | GFP | RD2 | GFP | RD2 | |||||||

| Embryo # | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B |

| E1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | +++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

| E2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | +++ | + | − | − | − | − |

| E3 | − | − | +++ | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ++++ |

| E4 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +++++ |

| E5 | − | − | − | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +++ |

| E6 | − | − | − | − | − | − | ++++ | − | − | − | − | − |

| E7 | − | − | N/A | N/A | − | − | − | − | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| E8 | − | N/A | N/A | N/A | − | − | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| E9 | − | − | N/A | N/A | − | − | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| E10 | N/A | N/A | N/A | − | − | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 0/9 | 0/9 | 1/6 | 2/6 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 3/7 | 2/7 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 3/6 | |

The “+” signs correspond to cells observed in any of those two regions. Although there were not many embryos showing RD2 cells in the gut (less than 50% of HH14 or HH16 embryos), HH14 had only two embryos with cells in area expressing Slit compared with HH16 sympathoadrenal or even more, HH17 sacral crest.

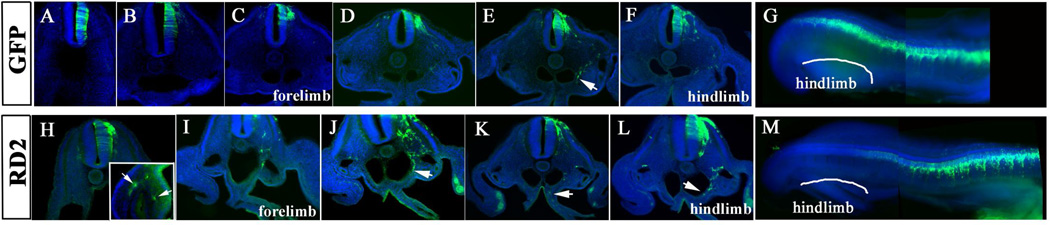

Embryos electroporated at HH14 (along somites 9–22), after vagal neural crest cells had migrated and before sacral crest appears, had few RD2 cells at the entrance of the gut past their sympathetic ganglia route (Fig.2H–L). The RD2 cells found in these embryos corresponds to trunk neural crest from somites 9–17. The migrating cells were found along their normal ventro-medial routes with few that had gone beyond, migrating ventral to the dorsal aorta and in one instance we found two cells settled in the plexus area of the stomach (Fig.2H insert). We only observed control GFP cells lateral to the dorsal aorta (Fig.2).

Figure 2. Whole mount and rostro-to-caudal sections of HH14 embryos.

Sections and whole mounts pictures for GFP and DAPI (blue) of HH14 electroporated embryos incubated for 24hrs. A–H shows a range of sections through control GFP embryo shown in G, forelimb (C) and hindlimb (F) sections are marked to highlight axial levels. G: shows the composite image of the embryo. H–L shows a range of sections through RD2 embryo shown in M, forelimb (I) and hindlimb (L) sections are marked to highlight axial levels. Arrows in J–L point to RD2 cells that migrated past trunk regions beneath the dorsal aorta. M: composite image of RD2 embryo showing posterior region of the embryo.

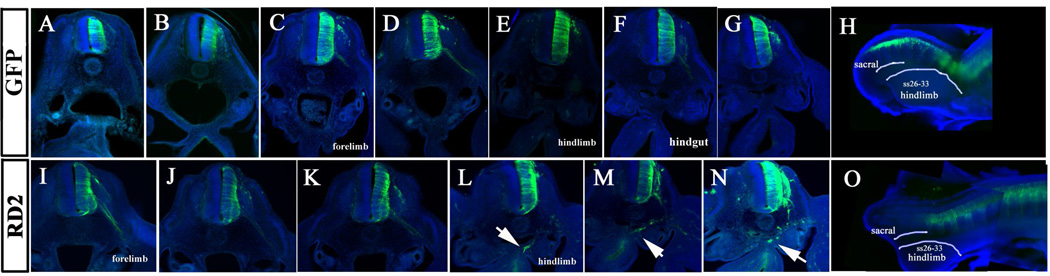

We repeated this experiment, but this time we electroporated HH16 embryos from the tail end, thus we were also electroporating the sympathoadrenal crest (somites 18–24) and few to none of the first sacral crest cells. In these embryos, we found larger numbers of RD2 cells along the gut mesenchyme at hindlimb levels compared with previous experiments with younger embryos (Fig.3). In these experiments we only observed RD2 cells in the hindgut region past the dorsal aorta, control embryos never showed GFP cells past the aorta. That is, sympathoadrenal crest cells were able to enter gut mesentery when we silenced Robo receptor.

Figure 3. Whole mount and rostro-to-caudal sections of HH16 embryos.

Sections and whole mounts pictures for GFP and DAPI (blue) of HH16 electroporated embryos incubated for 24hrs. A–G shows a range of sections through control GFP embryo shown in H, forelimb (C) and hindlimb (E) sections are marked to highlight axial levels. H: shows the composite image of the embryo with labels for sacral somite region and hindlimb somites (ss26–33). I–N shows a range of sections through RD2 embryo shown in O, forelimb (I) and hindlimb (L) sections are marked to highlight axial levels. Arrows in L–N point to RD2 cells that migrated past trunk regions into gut mesenchyme. O: composite image of RD2 embryo showing posterior region of the embryo with labels for sacral a hindlimb somites (ss26–33).

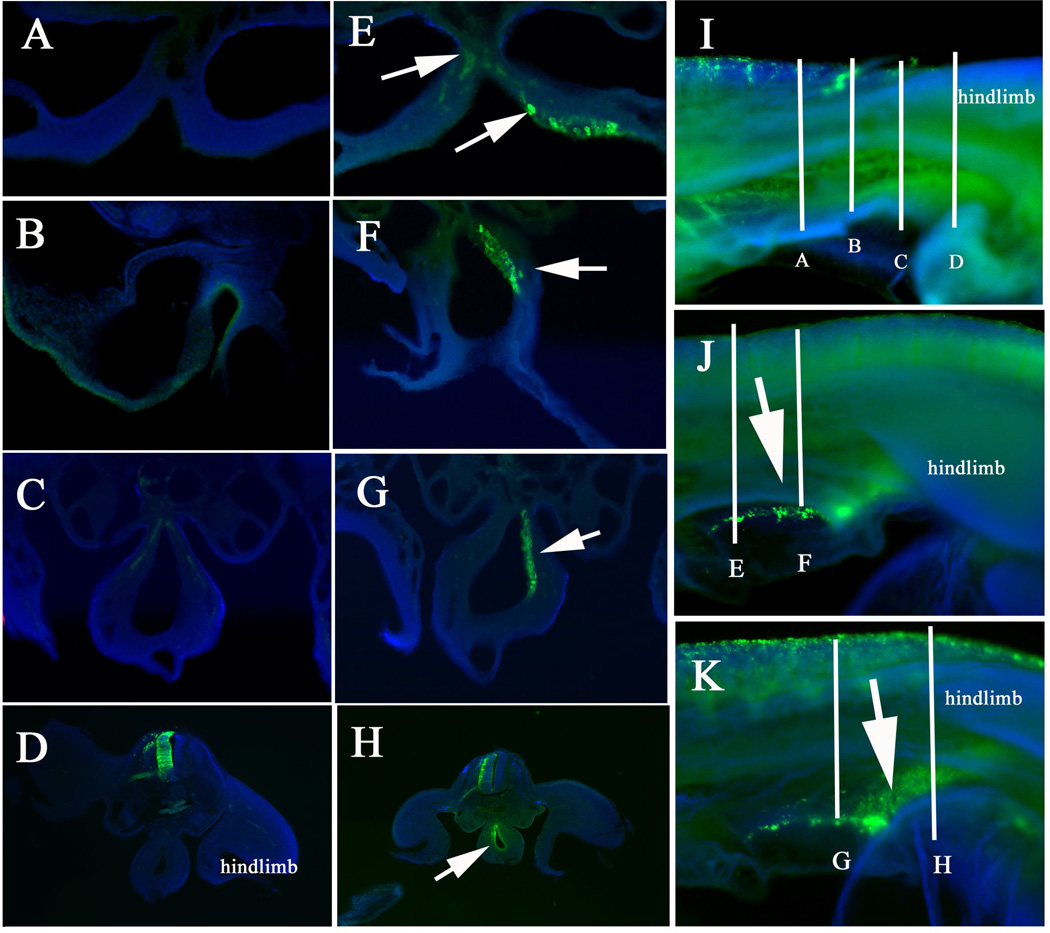

Embryos electroporated from above the hindlimb towards the tail at late HH17 and HH18 showed a more dramatic response: they had significantly larger numbers of RD2 cells and these were seen migrating rostrally. Because the time and area from where these cells are delaminating (hindlimb region, somites 24–33), these cells correspond to crest of sympathoadrenal fate and the first sacral neural crest cells. Sections through these embryos further corroborated the presence of many cells in developing gut of RD2 embryos compared with control embryos. The larger number of RD2 cells was more noticeable at same regions analyzed in previous experiments, past forelimb and before the hindlimb. That is, larger numbers of sympathoadrenal cells and sacral crest cells as well (Fig.4).

Figure 4. Sacral neural crest cells enter gut in Robo LOF embryos.

Sections and whole mounts pictures for GFP and DAPI (blue) of HH17 electroporated embryos incubated for 24hrs. A–D correspond to control GFP shown in I. E, F correspond to RD2 embryo shown in J while G, H correspond to embryo shown in K. AD Control GFP embryo does not have GFP cells in the gut folds. E, F RD2 embryos show GFP cells in the gut folds rostral to hindlimb (arrows). G, H RD2 embryos show GFP cells in the gut folds at hindlimb level (arrows). Lines and letters in I–K indicate corresponding section region in A–H.

3.3 Mice mutant for Slit or Robo show earlier development of enteric neurons

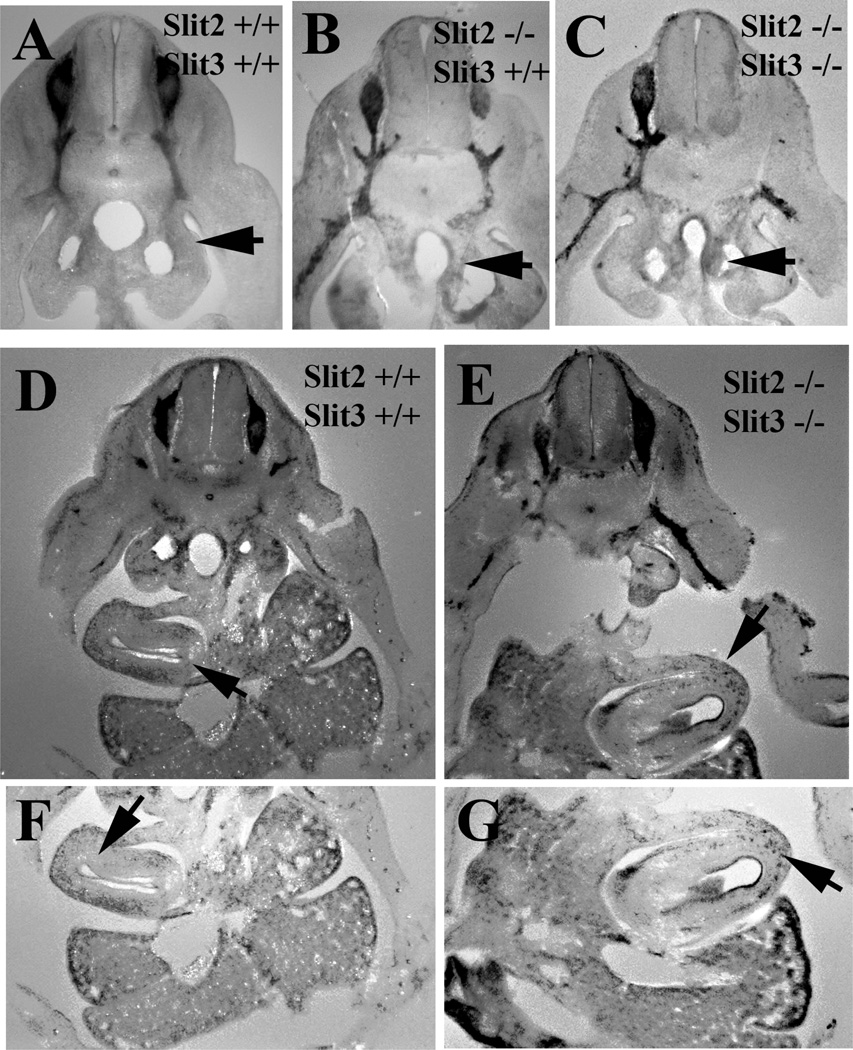

Although analysis of knockout mice cannot differentiate between vagal or trunk neural crests cells, nevertheless it can still provide strong supporting evidence for our hypothesis. We looked at E12.5 Slit triple knockout and Robo1/2 knockout mutant mice, whole mounts of these mutant animals did not show striking differences in the trunk migration (data not shown). However, sections through Slit mutant embryos at the midtrunk level showed the presence of Sox10 cells in the gut mesenchyme of mutant mice (either Slit1−/−, Slit2−/−, Slit3−/− or Slit1−/−, Slit2−/−, Slit3+/+) compared with littermate embryos lacking only Slit1 (Slit1−/−, Slit2+/+, Slit3+/+) (Fig.5A–C). We also observed that in mutant mice, at the level of lungs, the triple knockout mice have stronger Sox10 cells in the gut, already starting to look like enteric plexus, while counterparts missing only Slit1 had fewer Sox10 cells (Fig.5D–G).

Figure 5. Slit mutant mice have altered enteric neural crest cell migration.

Sections through whole mount in situ hybridization for Sox10 in E12.5 Slit1 mutant (A) and mice mutant for Slit1,2,3 (B, C) showed that neural crest cells were in larger number at the gut mesenchyme compared with no detectable Sox10 cells in Slit1 mutant embryo (arrows in A–C). All mice were Slit1 −/− background. D–G: Sections at more rostral level (lung region) show the presence of many Sox10 cells in Slit triple knockout mouse compared with Slit1 mutant (arrows in D–G). F, G corresponds to higher magnification of gut region by lung from D, E, notice that in control mouse there is no clear plexus forming (F), while it is quite advanced in the triple mutant (G).

In order to determine if the colonization of the gut by trunk neural crest cells was Robo-dependent, we examined neural crest migration in double knockout mice for Robo1 and Robo2 with Tuj1 (which labels differentiated neurons). We observed the presence of larger number of Sox10 positive cells in the gut (data not shown) and differentiated enteric neurons determined by TuJ1 (Supplementary Figure 1). We counted the Tuj1-positive cells in the developing mid-gut in mice and found that there were more in mutants compared with control wild type mice (wildtype 2.3+3.1 versus knockout 12+4.8, p<0.001 T-test). These observations from mutant Slit and Robo mice give great support for Slit/Robo role in neural crest cell migration during ENS development.

4. Discussion

It has been known that neural crest cells delaminating from trunk region (somites 8–27) will not enter or populate the developing gut of an embryo (Bronner-Fraser et al., 1991; Le Douarin et al., 1992; Le Douarin and Teillet, 1973). Although past research showed that Slits were true chemo-repulsive molecules for trunk neural crest cells, we were not certain that the reason why trunk crest cells would never continue migrating past the dorsal aorta and thus enter the developing mesentery was due to Slit molecules expression in that region (De Bellard et al., 2003). Here we show by carrying loss-of-function (LOF) experiments for Robo2 in chicken embryos that trunk sympathoadrenal neural crest cells can enter and populate the developing gut, thus demonstrating that Slit molecules are responsible for keeping trunk neural crest cells away from the gut.

The role of Slit/Robo signaling in keeping trunk crest away from developing gut has been investigated by comparing vagal versus trunk neural crest cells response to Slit molecules (De Bellard et al., 2003) and by carrying out gain-of-function experiments by over-expressing Slit or Robo in vagal and trunk neural crest (Giovannone et al., 2012). However, the findings from both studies did not settle the question whether Slit have a role in keeping trunk neural crest from migrating into the gut. Because neural crest cell practically did not delaminate when constitutively expressing Robo we were not able to test if vagal crest expressing Robo would never enter the gut (Giovannone et al., 2012). Therefore we needed to take a different approach to test this hypothesis. Here we addressed this caveat by silencing Slit/Robo signaling via Robo2 dominant negative receptor (RD2) and by looking at neural crest migration and ENS development in Robo1/2 or Slit1–3 knockout mice during early stages of ENS formation. Our results showing the presence of trunk neural crest cells in the developing gut after silencing Robo2 in chicken embryos confirms that Slit molecules are responsible for keeping trunk cells away from the gut.

4.1 Trunk Neural Crest Cells

Because the complexity of the neural crest itself as a stem cell population and because its inherent differences along its rostro to caudal origin, we electroporated at three different stages and locations (McKinney et al., 2013). The first thing we observed was that trunk neural crest cells rarely entered the gut, less than 50% of embryos showed RD2 cells in regions expressing Slit molecules. This was in stark contrast to what we observed when we silenced Robo2 in the caudal sympathoadrenals and sacral trunk crest: they entered Slit expressing region and the gut in larger numbers and migrated rostrally along the developing gut. Thus, silencing Robo in migrating trunk crest cells from somites 18–24 (sympathoadrenal) allowed a these cells to enter the developing gut. This kind of observation leads to say that Slit molecules are responsible for keeping the sympathoadrenal trunk cells (ss 18–24) from entering the gut.

One puzzling observation from our Robo LOF experiments was contrary to what we were expecting to observe: the developing gut being colonized by large number of trunk RD2 GFP-positive cells in most of our experimental embryos. Regardless of the stage at electroporation, we always observed small numbers of RD2-GFP trunk crest cells from somites 8–17 within gut mesenchyme region. This could be due to two possible reasons working in conjunction. One stemming from the fact that, as shown by Newgreen and co-workers, trunk cells fail to match vagal crest cells in proliferation once in the intestinal tissue (Newgreen et al., 1980; Zhang et al., 2010). It is known that most of the enteric neural crest cells are generated later in development from few vagal neural crest pioneers migration as a rostro-caudal wave in the developing gut (Barlow et al., 2008; Burns and Le Douarin, 2001; Serbedzija et al., 1991). We now know that one reason for this differential proliferation in the gut is because sacral neural crest cells have low levels of Ret receptor compared with vagal crest (Delalande et al., 2008). Thus, the few trunk RD2 cells that entered the gut likely failed to proliferate and never increased in numbers. The second one could be due to combination of guidance cues yet unknown that prevent/guide trunk crest cells at the end of their ventromedial migratory pathways. This is very likely given the known redundancy of repulsive molecules along the migratory pathways of trunk neural crest cells (Kulesa and Gammill, 2010).

Altogether, this leads us to propose that that there must be other guiding molecules to get trunk neural crest cells pass the mesentery region. This could well be another repellant present in the mesentery in conjunction with Slits, which combined with lack of strong chemoattraction to the gut itself prevented cells expressing RD2 from populating the gut in significant numbers. This is not unlikely given that neural crest cells are very plastic and variant along their rostro-caudal axis (Le Douarin et al., 2004).

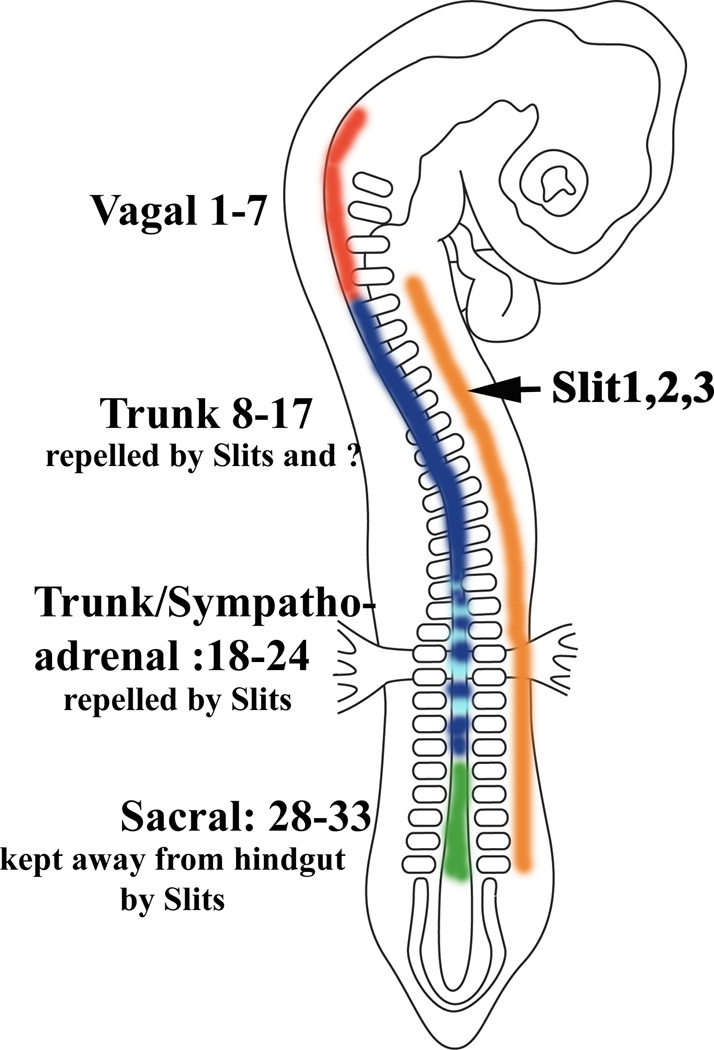

The second interesting observation from this research was that sympathoadrenals trunk cells expressing RD2 were present in larger numbers than its more rostral counterparts in Slit expressing regions ventral to the dorsal aorta and even gut mesenchyme. These suggest that silencing Slit/Robo signaling in them was sufficient to allow them to enter and colonize the gut. Le Douarin’s seminal trunk to vagal transplant study was indeed done with “adrenomedullary” trunk cells (ss18–24), they did not transplant more rostral neural tubes (Le Douarin and Teillet, 1974a). Our findings that at HH10–12 that there is no expression of Slit1/2 in the developing pharynx explains why these trunk cells (which express Robo) could enter the gut when transplanted to vagal region that lacks Slit inhibitory expression. We would like to propose here that Slit molecules are mostly responsible for keeping adrenomedullary (ss18–24) crest away from entering the gut in a different manner to which more rostral trunk neural crest cells are (see Fig.6 Graphical abstract).

Figure 6. Graphical abstract.

The graphical abstract summarizes what we know about Slit/Robo interaction in neural crest migration into the gut: at vagal levels neural crest cells enter the gut by migrating through area without Slit expression. Trunk neural crest cells before somite 18 are repelled by Slits as well as another yet unknown factor(s). The trunk neural crest between somite 17–24 (sympathoadrenal) is kept away from the gut by Slit molecules as well as sacral crest is prevented from populating the gut before vagal crest arrives by Slit expression along the gut mesenchyme.

Our observations of the neural crest phenotype in Slit or Robo knockout mice gave support a role for Slit/Robo interaction in their development. We observed: a) larger sympathetic ganglia by E10.5 in Slit mutants, b) more differentiated neurons in the Robo mutant gut and c) larger proportion of neural crest cells in the differentiating gut in the Slit mutant mice (Druckenbrod and Epstein, 2007). However, as in the instance of using RD2, we did not observe much larger numbers of Sox10 or TuJ1 in the developing gut of the mutant mice. Despite these initial neural crest abnormalities in Robo 1/2 knockout mice, as development progresses they likely adjust cell numbers since these double knockout mice are born without hypergangliosis in either DRGs or ENS (Geisen et al., 2008; Long et al., 2004). Thus, it is assumed, as has proven for many other mutant knockout lines, that there is either compensation of Slit/Robo functions (Sabatier et al., 2004) and likely increased cell death from lack of required neurotrophic factors (NGF. GDNF, etc.) (Levi-Montalcini, 1987; Rich et al., 1987). The case for triple Slit knockout mice is different; mutant embryos do not grow to E13, making these triple knockout a lethal phenotype (Long et al., 2004).

4.2 Sacral Neural Crest

Past work from Bronner’s lab showed that embryos injected with DiI at HH17, as in these experiments, showed labeled cells only in the more caudal levels of the gut, with cells within the gut mesenchyme and epithelium (Serbedzija et al., 1991). From the early 1970s Le Douarin and co-workers elegantly showed that sacral neural crest cells migrate in a caudal-to-rostral direction during days E4–6 and will only begin to enter the gut at E7 (Burns et al., 2000; Burns and Le Douarin, 2001; Le Douarin and Teillet, 1973; Rothman et al., 1993). Our RD2 GFP cells from HH17–18 electroporations were present at same anatomical locations found in quail-chick chimeras, virus or DiI experiments: developing gut epithelium (Serbedzija et al., 1991) and gut mesenchyme (Burns et al., 2000; Burns and Douarin, 1998; Burns and Le Douarin, 2001; Pomeranz et al., 1991). However, the key point is that we found these RD2 cells in large numbers 24 hrs. sooner than what is expected from their stage of development. Our findings of large number of sacral crest at the hindlimb level by E4 supports a role for Slit repellants in delaying sacral crest from invading rostral gut mesenchyme ahead of vagal neural crest caudal migration (Allan and Newgreen, 1980; Barlow et al., 2008).

Furthermore, classic transplants studies carried out by Erickson and Goins found that sacral crest grafted to sympathoadrenal level would not pass beyond beneath the dorsal aorta, that is, they are repelled from entering the gut (Erickson and Goins, 2000a) as trunk crest cells are. Here we show that RD2 electroporated sacral neural crest invaded gut mesenchyme and epithelium but in much larger numbers than what was observed in those transplants with labeled cells. This finding suggests that sacral neural crest cells are also kept from migrating rostrally by Slit molecules expression in the gut mesenchyme.

5. Conclusions

The results show for the first time that: 1) Adrenomedullary trunk neural crest cells (ss18–24) can enter the gut if Slits Robo receptors are silenced. 2) More rostral trunk neural crest cells (ss9–17) are kept away from entering the gut likely by other factors (either another yet unknown repellent and/or lack of sufficient attraction). 3) Sacral neural crest cells are kept away from populating the colon region by Slit molecules. 4) Enteric neural crest cells express Robo receptors once they start forming their plexus. Thus these results give account for the differential ability of vagal but not trunk neural crest cells to invade and innervate the gut. In summary, we can conclude that Slit molecules are responsible for keeping migrating trunk neural crest cells away from the gut and sacral from entering rostral portions of the gut before vagal enteric crest reach the hind gut.

Supplementary Material

Sections of E10.5 wild-type or double mutant mice for Robo1/2 were immunostained with Tuj1 to label differentiated neurons. Robo mutant mice had more Tuj1 labeled neurons (A) in the developing gut compared with wildtype littermate at the heart level (B). arrows point to Tuj1 labeling.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ed Laufer for Slits and Robo probes and Sarah Guthrie for RoboDelta2 plasmid. We thank Vivian Lee for help with in situ hybridization. This work was supported by an NIH/NINDS AREA grant 1R15-NS060099-02 to MEdB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nora Zuhdi, California State University Northridge, Biology Dept., MC 8303. 18111 Nordhoff Street. Northridge, CA 91330.

Blanca Ortega, California State University Northridge, Biology Dept., MC 8303. 18111 Nordhoff Street. Northridge, CA 91330.

Dion Giovannone, California State University Northridge, Biology Dept., MC 8303. 18111 Nordhoff Street. Northridge, CA 91330.

Hannah Ra, California State University Northridge, Biology Dept., MC 8303. 18111 Nordhoff Street. Northridge, CA 91330.

Michelle Reyes, California State University Northridge, Biology Dept., MC 8303. 18111 Nordhoff Street. Northridge, CA 91330.

Viviana Asención, California State University Northridge, Biology Dept., MC 8303. 18111 Nordhoff Street. Northridge, CA 91330.

Ian McNicoll, California State University Northridge, Biology Dept., MC 8303. 18111 Nordhoff Street. Northridge, CA 91330.

Le Ma, Department of Neuroscience. Thomas Jefferson University, BLSB 306. Philadelphia, PA 19107.

Maria Elena de Bellard, California State University Northridge, Biology Dept., MC 8303. 18111 Nordhoff Street. Northridge, CA 91330.

References

- Allan IJ, Newgreen DF. The origin and differentiation of enteric neurons of the intestine of the fowl embryo. Am J Anat. 1980;157:137–154. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001570203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow AJ, Wallace AS, Thapar N, Burns AJ. Critical numbers of neural crest cells are required in the pathways from the neural tube to the foregut to ensure complete enteric nervous system formation. Development. 2008;135:1681–1691. doi: 10.1242/dev.017418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner-Fraser M, Stern CD, Fraser S. Analysis of neural crest cell lineage and migration. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1991;11:214–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose K, Bland KS, Wang KH, Arnott D, Henzel W, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M, Kidd T. Slit proteins bind Robo receptors and have an evolutionarily conserved role in repulsive axon guidance. Cell. 1999;96:795–806. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns AJ. Migration of neural crest-derived enteric nervous system precursor cells to and within the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Dev Biol. 2005;49:143–150. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041935ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns AJ, Champeval D, Le Douarin NM. Sacral neural crest cells colonise aganglionic hindgut in vivo but fail to compensate for lack of enteric ganglia. Dev Biol. 2000;219:30–43. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns AJ, Delalande JM, Le Douarin NM. In ovo transplantation of enteric nervous system precursors from vagal to sacral neural crest results in extensive hindgut colonisation. Development. 2002;129:2785–2796. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.12.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns AJ, Douarin NM. The sacral neural crest contributes neurons and glia to the post- umbilical gut: spatiotemporal analysis of the development of the enteric nervous system. Development. 1998;125:4335–4347. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.21.4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns AJ, Le Douarin NM. Enteric nervous system development: analysis of the selective developmental potentialities of vagal and sacral neural crest cells using quail-chick chimeras. Anat Rec. 2001;262:16–28. doi: 10.1002/1097-0185(20010101)262:1<16::AID-AR1007>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellard ME, Rao Y, Bronner-Fraser M. Dual function of Slit2 in repulsion and enhanced migration of trunk, but not vagal, neural crest cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:269–279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delalande JM, Barlow AJ, Thomas AJ, Wallace AS, Thapar N, Erickson CA, Burns AJ. The receptor tyrosine kinase RET regulates hindgut colonization by sacral neural crest cells. Dev Biol. 2008;313:279–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druckenbrod NR, Epstein ML. Behavior of enteric neural crest-derived cells varies with respect to the migratory wavefront. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:84–92. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickholt BJ, Mackenzie SL, Graham A, Walsh FS, Doherty P. Evidence for collapsing-1 functioning in the control of neural crest migration in both trunk and hindbrain regions. Development. 1999;126:2181–2189. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.10.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson CA, Goins TL. Sacral neural crest cell migration to the gut is dependent upon the migratory environment and not cell-autonomous migratory properties. Dev Biol. 2000a;219:79–97. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson CA, Goins TL. Sacral neural crest cell migration to the gut is dependent upon the migratory environment and not cell-autonomous migratory properties. Dev Biol. 2000b;219:79–97. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammill LS, Gonzalez C, Gu C, Bronner-Fraser M. Guidance of trunk neural crest migration requires neuropilin 2/semaphorin 3F signaling. Development. 2006;133:99–106. doi: 10.1242/dev.02187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammill LS, Roffers-Agarwal J. Division of labor during trunk neural crest development. Dev Biol. 2010;344:555–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisen MJ, Di Meglio T, Pasqualetti M, Ducret S, Brunet JF, Chedotal A, Rijli FM. Hox paralog group 2 genes control the migration of mouse pontine neurons through slit-robo signaling. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannone D, Reyes M, Reyes R, Correa L, Martinez D, Ra H, Gomez G, Kaiser J, Ma L, Stein MP, de Bellard ME. Slits affect the timely migration of neural crest cells via Robo receptor. Dev Dyn. 2012;241:1274–1288. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A series of normal stages in the development of the chicken embryo. J. Morph. 1951;88:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond R, Vivancos V, Naeem A, Chilton J, Mambetisaeva E, Andrews W, Sundaresan V, Guthrie S. Slit-mediated repulsion is a key regulator of motor axon pathfinding in the hindbrain. Development. 2005;132:4483–4495. doi: 10.1242/dev.02038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Cheng L, Raper J. Slit/Robo signaling is necessary to confine early neural crest cells to the ventral migratory pathway in the trunk. Dev Biol. 2005;282:411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd T, Bland KS, Goodman CS. Slit is the midline repellent for the robo receptor in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;96:785–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinrade EF, Brates T, Tear G, Hidalgo A. Roundabout signalling, cell contact and trophic support confine longitudinal glia and axons in the Drosophila CNS. Development. 2001;128:207–216. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull CE, Lansford R, Gale NW, Collazo A, Marcelle C, Yancopoulos GD, Fraser SE, Bronner-Fraser M. Interactions of Eph-related receptors and ligands confer rostrocaudal pattern to trunk neural crest migration. Curr Biol. 1997;7:571–580. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesa PM, Gammill LS. Neural crest migration: patterns, phases and signals. Dev Biol. 2010;344:566–568. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo BR, Erickson CA. Regional differences in neural crest morphogenesis. Cell Adh Migr. 2010;4:567–585. doi: 10.4161/cam.4.4.12890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo BR, Erickson CA. Vagal neural crest cell migratory behavior: a transition between the cranial and trunk crest. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:2084–2100. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Creuzet S, Couly G, Dupin E. Neural crest cell plasticity and its limits. Development. 2004;131:4637–4650. doi: 10.1242/dev.01350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Dupin E, Baroffio A, Dulac C. New insights into the development of neural crest derivatives. Int Rev Cytol. 1992;138:269–314. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61591-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Teillet M-AM. Experimental analysis of the migration and differentiation of neuroblasts of the autonomic nervous system and of neurectodermal mesenchymal derivatives, using a biological cell marking technique. Dev Biol. 1974a;41:162–184. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(74)90291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Teillet MA. The migration of neural crest cells to the wall of the digestive tract in avian embryo. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1973;30:31–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Teillet MA. Experimental analysis of the migration and differentiation of neuroblasts of the autonomic nervous system and of neuroectodermal mesenchymal derivatives, using a biological cell marking technique. Dev Biol. 1974b;41:162–184. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(74)90291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Montalcini R. The nerve growth factor 35 years later. Science. 1987;237:1154–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.3306916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long H, Sabatier C, Ma L, Plump A, Yuan W, Ornitz DM, Tamada A, Murakami F, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M. Conserved roles for Slit and Robo proteins in midline commissural axon guidance. Neuron. 2004;42:213–223. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney MC, Fukatsu K, Morrison J, McLennan R, Bronner ME, Kulesa PM. Evidence for dynamic rearrangements but lack of fate or position restrictions in premigratory avian trunk neural crest. Development. 2013;140:820–830. doi: 10.1242/dev.083725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newgreen DF, Jahnke I, Allan IJ, Gibbins IL. Differentiation of sympathetic and enteric neurons of the fowl embryo in grafts to the chorio-allantoic membrane. Cell Tissue Res. 1980;208:1–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00234168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeranz HD, Rothman TP, Gershon MD. Colonization of the post-umbilical bowel by cells derived from the sacral neural crest: direct tracing of cell migration using an intercalating probe and a replication-deficient retrovirus. Development. 1991;111:647–655. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.3.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich KM, Luszczynski JR, Osborne PA, Johnson EM., Jr Nerve growth factor protects adult sensory neurons from cell death and atrophy caused by nerve injury. J Neurocytol. 1987;16:261–268. doi: 10.1007/BF01795309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman TP, Le Douarin NM, Fontaine-Perus JC, Gershon MD. Colonization of the bowel by neural crest-derived cells re-migrating from foregut backtransplanted to vagal or sacral regions of host embryos. Dev Dyn. 1993;196:217–233. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001960308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier C, Plump AS, Le M, Brose K, Tamada A, Murakami F, Lee EY, Tessier-Lavigne M. The divergent Robo family protein rig-1/Robo3 is a negative regulator of slit responsiveness required for midline crossing by commissural axons. Cell. 2004;117:157–169. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbedzija GN, Burgan S, Fraser SE, Bronner-Fraser M. Vital dye labelling demonstrates a sacral neural crest contribution to the enteric nervous system of chick and mouse embryos. Development. 1991;111:857–866. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.4.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau CE, Lwigale PY, Das RM, Wilson SA, Bronner-Fraser M. Robo2-Slit1 dependent cell-cell interactions mediate assembly of the trigeminal ganglion. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:269–276. doi: 10.1038/nn2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theveneau E, Mayor R. Neural crest migration: interplay between chemorepellents, chemoattractants, contact inhibition, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and collective cell migration. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology. 2012;1:435–445. doi: 10.1002/wdev.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Brinas IM, Binder BJ, Landman KA, Newgreen DF. Neural crest regionalisation for enteric nervous system formation: implications for Hirschsprung's disease and stem cell therapy. Dev Biol. 2010;339:280–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Li H, Zhou L, Wu JY, Rao Y. Cellular and molecular guidance of GABAergic neuronal migration from an extracortical origin to the neocortex. Neuron. 1999;23:473–485. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80801-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sections of E10.5 wild-type or double mutant mice for Robo1/2 were immunostained with Tuj1 to label differentiated neurons. Robo mutant mice had more Tuj1 labeled neurons (A) in the developing gut compared with wildtype littermate at the heart level (B). arrows point to Tuj1 labeling.