Abstract

Previous studies have linked heat waves to adverse health outcomes using ambient temperature as a proxy for estimating exposure. The goal of the present study was to test a method for determining personal heat exposure. An occupationally exposed group (urban groundskeepers in Birmingham, AL, USA N=21), as well as urban and rural community members from Birmingham, AL (N=30) or west central AL (N=30) wore data logging temperature and light monitors clipped to the shoe for 7 days during the summer of 2012. We found that a temperature monitor clipped to the shoe provided a comfortable and feasible method for recording personal heat exposure. Ambient temperature (°C) recorded at the nearest weather station was significantly associated with personal heat exposure [β 0.37, 95%CI (0.35, 0.39)], particularly in groundskeepers who spent more of their total time outdoors [β 0.42, 95%CI (0.39, 0.46)]. Factors significantly associated with lower personal heat exposure include reported time indoors [β −2.02, 95%CI (−2.15, −1.89)], reported income > 20K [β −1.05, 95%CI (−1.79, −0.30)], and measured % body fat [β −0.07, 95%CI (−0.12, −0.02)]. There were significant associations between income and % body fat with lower indoor and nighttime exposures, but not with outdoor heat exposure, suggesting modifications of the home thermal environment play an important role in determining overall heat exposure. Further delineation of the effect of personal characteristics on heat exposure may help to develop targeted strategies for preventing heat-related illness.

Keywords: personal exposure, outdoor versus indoor exposure, sunlight exposure, heat exposure, occupational heat exposure

INTRODUCTION

Heat-related illness (HRI) is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. During 2004–2005, there were an estimated 10,007 hyperthermia health care visits from Medicare beneficiaries (60% of which were in the South), with an estimated health care cost of $36 million(Noe et al., 2012). Minorities, particularly Black individuals, are most at risk for hyperthermia (Knowlton et al., 2009; Noe et al., 2012). Heat waves also exacerbate chronic conditions, significantly contributing to cardiovascular and respiratory mortality and morbidity (Basu, 2009; Reid et al., 2012). In North Carolina, the daily number of emergency department visits for HRI was estimated to increase by 16 for each 1°F the temperature rose above 98°F (Rhea, 2012). In 2012, 809 heat-related illnesses and 6 deaths were reported to the Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH) (ADPH, 2012). Surprisingly, 80% of the cases are between the ages of 15 and 59, and 43% were reported as work-related. In addition, rates of heat-illness were higher in rural counties. However, heat related illnesses are often not coded and thus may be underestimated(Ye et al., 2012). It is unclear how demographic and behavioral risk factors interact with exposure to determine overall risk.

Most epidemiological studies that have demonstrated increased mortality and morbidity during heat waves have used percentile-based exceedances of daily average temperatures derived from nearby weather station datasets as the exposure estimate (Anderson and Bell, 2011; Peng et al., 2011; Reid et al., 2012). Weather stations provide accurate information on meteorological conditions within a limited radius from each station and real time estimates can be communicated to protect the public’s health. However, since individuals spend a limited amount of time in close proximity to weather stations, they may not represent an individual’s “true” ambient exposure throughout the day, leading to misclassification in epidemiological analyses. This exposure metric provides an imperfect proxy for heat exposure experienced by individuals because: 1) other weather parameters, including increased humidity, decreased wind speed and increased solar radiation, are known to heighten risk of heat illness (Budd, 2008), 2) different types of land cover within communities create microclimates that can substantially affect heat exposure (Tomlinson et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011), and 3) most individuals move between a wide range of indoor and outdoor thermal environments daily. These limitations may result in exposure misclassification and possible dilution of any true effects in epidemiological studies looking to define exposure-response relationships. Exposure misclassification is a well-known issue that has been addressed with personal monitors in air pollution studies (Lioy et al., 2011), but has been less explored in the current heat wave literature.

The research presented herein evaluates the feasibility of personal heat exposure measurement using a temperature and light data logger attached to the shoe. We examine differences between weather station measurements and estimates of personal heat exposure in urban Birmingham AL and rural West Central Alabama communities. We also evaluate differences in outdoor, indoor, and nighttime heat exposure in urban and rural environments and in an outdoor worker population, and explore the association between personal characteristics, such as body composition and socioeconomic status, and heat exposure. Finally, since previous studies have shown the utility of light exposure as a measure of time outside versus indoors (Cleland et al., 2008; Cleland et al., 2010; Schmid et al., 2013), we examined whether light intensity measurements are associated with daily log estimates of time spent outdoors.

METHODS

Study Populations

Eighty-one participants were recruited in total. Participants were recruited by community partners Friends of West End (FOWE) in Birmingham AL (N=30) and West Central Alabama Community Health Improvement League (WCACHIL) in West Central Alabama (N=30), and represent urban dwelling and rural participants, respectively. City of Birmingham groundskeepers (N=21) were recruited to represent an outdoor worker population. Outdoor work was conducted from 6 am to 2 pm Monday–Friday and included general landscape upkeep (e.g. mowing, mulch spreading, weeding) of City of Birmingham properties. Recruitment: Flyers and word of mouth identified prospective participants. Potential participants were excluded based on medical conditions or medication use that may limit the time they could spend outside. Prospective participants were asked to attend a 1.5 hour check-in session where a presentation of the study was given, the consent process was described and witnessed, a demographic questionnaire was filled out, and physical measurements were taken. All participants who attended the session decided to participate in the study. This study was reviewed and approved by the UAB Institutional Review Board (X120513012 and X120217008).

Individual exposure measurements: temperature/light monitors

There were 3 weeks of participation confined to the mid-summer (July 18th–Aug 7th) to limit seasonal variability as much as possible. Participants were asked to wear a HOBO® Pendant temperature/light data logger (Onset Corp. UA-002-64) clipped to their shoes, for 7 consecutive days (Wed-Tues) from July 18 to 24, July 25 to July 31, or Aug 1 to Aug. 7, 2012. Pendant monitors were set to record temperature (degrees C) and light intensity (lux) each minute. Based on manufacturer specifications, monitors can detect temperatures ranging from −20° to 70°C with accuracy of 0.47°C and resolution of 0.10°C at 25°C. Four monitors in the same controlled temperature indoor location over a 5 day period gave an average standard deviation between monitor readings of 0.04°C. Daily activity logs: Participants were also asked to keep a daily log of activities. Daily log sheets had hourly time increments where participants were asked to check a box of either indoors or outdoors, and write a brief line description of their activity and location.

Compliance

Participants were called twice during the week to ask if they were having any trouble wearing the monitors or recording activities on the daily log sheets. At the turn-in session, participants were asked a series of questions relating to comfort and compliance in wearing the monitors.

Body measurements

Participants’ height and weight and body composition (including % body fat), were recorded at the check-in session, using a fold-up height stick and Befour Inc. Model #PS660 scale, and Tanita BC-553 portable body composition scale, respectively. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/ [height (m)]2 (Gallagher D, 1996).

Weather station datasets

To compare personal heat exposure estimates with weather station datasets, hourly mean, maximum, and minimum temperatures recorded at the Birmingham, AL airport weather station and Thomasville, AL weather station from July 18 to Aug. 7, 2012 were downloaded from the National Climate Date Center Surface Data, Hourly Global dataset (DS3505) (http://cdo.ncdc.noaa.gov/). These weather stations are the closest weather stations to the urban and rural study populations that record temperatures at 5 min. increments to derive hourly data.

Data Analysis

Average, maximum, and minimum temperatures and light intensities from data loggers were calculated for each hour to generate a total of 12,826 person-hours of personal temperature and light intensity data. Two monitors (1 each from a groundskeeper and a rural participant) were unable to be read, likely due to damage or malfunction of the monitor. Personal monitors included in the analyses were examined separately for groundskeepers (n=3,147 hours), rural (n=4,801 hours), and urban (n=4,878 hours) study samples. Mean temperature distributions were examined using scatterplots, and data points with temperatures exceeding 50°C were considered invalid values and excluded from analysis (18 person-hours total). Four hours were removed from a rural participant, 11 and 2 hours were removed from two urban participants, respectively, and 1 hour was removed from a groundskeeper. Light intensity measurements were treated as a continuous variable or were categorized based on four different cutoffs (200, 500, 1000200, 500, 2000 lux) from previous literature assessing the relationship between light intensity levels and time spent outdoors (Cleland et al., 2008; Cleland et al., 2010; Schmid et al., 2013).

The hourly daily log data was matched to the hourly monitor data based on 3 broad categories: “in transit”, “indoor”, or “outdoor”. If the participant reported traveling in a car or on foot, then the hour was classified as “in transit”, otherwise the participants’ hour was classified according to the marked indoor/outdoor boxes. Missing hourly descriptions (10.2% (440 of 4299) urban, 3.1% (133 of 4320) rural, and 2.4% (67 of 2757) groundskeeper) were estimated using last observation carried forward, in that the previous hour’s activity was carried forward. Two groundskeepers and two rural community members were excluded from this analysis due to inability to read out the monitor data for comparison thus, there were a total of 11,376 person-hours of data from 19 groundskeepers, 30 rural and 28 urban participants. This resulted in 4299, 4320, and 2757 person-hours of matched daily log to monitor data for urban, rural, and groundskeepers, respectively.

Descriptions of activities on the daily logs were additionally coded into 14 subcategories including indoor (home, work, visiting a friend/ relative, Church, store, and other), outdoor (work, recreation, visiting a friend/ relative, activities, and shop), and in-transit (vehicle, walking and work). Subcategories were initially based on (Basu and Samet, 2002) and were further refined based on activities commonly reported by participants in the present study. The authors developed a decision tree to systematically categorize the daily logs at an hourly level. When more than 2 activities were recorded in an hour, the initial activity was considered for the hour. In-transit was differentiated into in-transit in-vehicle (for personal commuting and for employment) and in-transit on foot. Since vehicle in transit time was minimal and temperatures experienced were similar to indoor time, these were combined in the final regression analyses. Two urban community participants and 2 groundskeeper participants were not included in this microenvironment analysis as less than 50% of their activity hours were recorded in their daily logs. A total of 9,912 person-hours were available for this more detailed microenvironment analysis.

Linear mixed models were fitted to determine factors significantly associated with personal heat and light exposure across urban, rural and groundskeeper populations, allowing us to account for multiple measurements within a single person. For each model, the dependent variable was either hourly mean temperature (°C) or hourly light measurement (lux) from the personal data loggers. Individual level data was matched to weather station data at the hourly time scale and models included a random effect term, allowing the intercept to vary for each individual. The overall model for personal hourly mean temperature takes the form of:

where yim is the dependent variable across all measures over time i (i=1,2,..,12,826) for all subjects m (m = 1,2…,78), βo is the intercept, and βj (j = 0, 1, ..., 8) are the fixed-effects coefficients, b0m are random effects, and εim is the error term. A compound symmetric covariance matrix was used to account for correlation among the random effects. WS is the nearest weather station hourly mean temperature (°C), BF is % body fat, and AG is age in years. I[ID]im is the dummy variable representing indoor location with outdoor as the reference group as marked on the daily log record (marked either 1. inside/in-transit or 2. outside), I[IC]im is income category (> $20,000 vs. < $20,000 reported annual income), I[ED]im is education (> high-school diploma vs. ≤ high school diploma), and I[SX]im is sex reported as female, and weekend I[WN] im is weekend versus weekday. Week was not included in the analysis due to minimal variability in weather station temperatures across the 3 weeks (daily average temperatures in Birmingham 26.7±3.5°C and Camden 26.3±3.6°C). Models were stratified by group (GP) (urban community, rural community, urban groundskeepers) for examination of personal heat exposure across urban/rural environment and across occupationally and non-occupationally exposed groups.

In additional models of personal heat exposure, hourly light measurements were added to account for the radiant heat captured by the personal monitors but not at weather station monitor sites; however, because light and temperature measurements come from the same monitor, monitor-specific correlations between light and temperature measurements cannot be ruled out in these models. To evaluate indoor vs. outdoor vs. nighttime contributions to personal heat, separate models were run for outdoor and indoor personal heat exposure defined by daily log entries and nighttime heat exposure (between midnight and 5 AM) as the dependent variable. Light exposure was also evaluated as a dependent variable. Bivariate correlations between independent and dependent variables and between independent variables were evaluated, and since BMI and % body fat were highly correlated, only % body fat was added in final models. The fitlmematrix function in MATLAB R2013a was used to evaluate regression models. No adjustment was made for multiple testing due to the exploratory nature of the analysis.

RESULTS

Study population characteristics

Personal characteristics of study participants are summarized in Table 1. Participants recruited from urban and rural community study areas were similar in demographic characteristics (primarily low-income, African American women, between 40–60 years of age). City of Birmingham groundskeeper participants were primarily African American men with slightly higher income levels. Body Mass Index (BMI) and % body fat were high particularly in female participants, and 79% of participants were obese (BMI ≥30) and the rates of obesity were similar across the rural and urban participants. As shown in Table 1, rural participant residences were on average further away from the nearest weather station than the urban participant residences.

Table 1.

Demographics and measurements for temperature and sunlight exposure study participants in rural SW AL and urban Birmingham, AL during Summer 2012

| Parameter | Rural (SW Alabama) | Urban (Birmingham) | Birmingham groundskeepers |

|---|---|---|---|

| OVERALL | |||

| N | 30 | 30 | 21 |

| Median age (range), years | 52 (20, 65) | 50.5 (20, 64) | 44.5 (24, 57) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 5 (17%) | 5 (17%) | 18(86%) |

| Female | 25 (83%) | 25 (83%) | 3(14%) |

| % Black or African-American | 29 (97%) | 27(90%) | 19 (90%) |

| Education | |||

| Less than High School Diploma | 2 (7%) | 3 (10%) | 4 (19%) |

| High School Diploma (or GED or Equivalence) | 13 (43%) | 4 (13%) | 7 (33%) |

| Post-Secondary Certificate | 4 (13%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (10%) |

| Some College or Associate's Degree | 5 (17%) | 17 (57%) | 8 (38%) |

| Bachelor's Degree | 1 (3%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Graduate Degree | 5 (17%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Income | |||

| Less than $20,000 | 19 (66%) | 14 (47%) | 5 (24%) |

| $20,000 to $49,999 | 8 (28%) | 12 (40%) | 12 (57%) |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (19%) |

| $75,000 or more | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | 13(45%) | 15 (50%) | 21 (100%) |

| Unemployed | 16(55%) | 15 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

| Retired | 3(10%) | 4 (13%) | 0 (0%) |

| Distance (km) between stationary monitor and residence (Mean ± Standard deviation) | 58.6 ±30.0 | 12.3±4.3 | 10.0 ±5.9 |

| Body measurements median (range) | |||

| BMI | 34.9 (23.8–46.3) | 32.7 (21.2–50.9) | 30.1 (18.4–38.4) |

| % body fat | 44.7 (22–53.7) | 41.7 (19.3–55.5) | 30.6 (8.2–50.4) |

| AMONG FEMALES | |||

| Median age (range), years | 50 (20–65) | 51 (20–64) | 50 (40–53) |

| BMI | 35.3 (23.8–46.3) | 35.0 (21.2–50.9) | 36.1 (25.7–36.6) |

| % body fat | 47.0 (27.3–53.7) | 44 (26.3–55.5) | 44.9(37.8–50.4) |

| AMONG MALES | |||

| Median age (range), years | 52 (25–58) | 47 (44–62) | 44 (24–57) |

| BMI | 32.9 (26.0–36.6) | 25.6 (22.4–28.9) | 29.2 (18.3–38.4) |

| % body fat | 31.7 (22–37.7) | 23.3 (19.3–31.1) | 28.7 (8.2–38.4) |

Feasibility of method for estimating personal heat exposure

An exit survey was conducted to evaluate comfort, compliance, and perceived benefits of participation. Using a scale of 1–5, with 5 being very comfortable, most participants (91%) found wearing the monitor on their shoe was very comfortable and reported the monitor was not hard to remember to wear (88%); however, fifteen participants (19%) reported not remembering to wear their monitor at least once during the week. Over half of the participants (58%) reported becoming more aware of the time they spend indoors and outdoors upon receiving a graph of the output from the monitor they had worn at the turn-in session. A total of 4 monitors of the 81 were unable to be read. An additional 18 person-hours were removed due to extreme temperature (>50°C). In terms of daily logs, participants provided detailed activity information on their hourly logs for an average of 82% of the total hours (128 out of 156 hours total per participant) (Table 2). A total of 9,912 person-hours were available for this more detailed microenvironment analysis.

Table 2.

Linear mixed model fixed effect predictors of personal heat exposure across all participants, or within urban community member, rural community member, or groundskeeper participants (Alabama Summer 2012)

| All participants β (95% CI) | Urban community β (95% CI) | Rural community β (95% CI) | Groundskeeper participants β (95% CI) | |

| Weather station a | 0.37 (0.35, 0.39) | 0.37 (0.34, 0.39) | 0.38(0.36,0.40) | 0.42(0.39, 0.46) |

| Indoorsb | −2.02(−2.15, −1.89) | −1.97(−2.21,−1.73) | −0.87(−1.06,−0.68) | −3.48(−3.74,−3.22) |

| Income > 20K | −1.05(−1.79,−0.30) | −0.88(−2.23, 0.47) | −0.28(−1.57, 1.01) | −1.96(−3.30,−0.62) |

| Education> high school | 0.10(−0.65,0.86) | 0.83(−0.70, 2.36) | −0.41(−1.63, 0.81) | −0.19(−1.27, 0.90) |

| Female | −0.13 (−1.28, 1.03) | −1.60 (−4.16, 0.96) | −0.28(−2.12,1.56) | 0.07(−1.82, 1.96) |

| Weekend | −0.22(−0.34, −0.10) | 0.13(−0.07,0.33) | −0.14(−0.31,0.03) | −0.60(−0.87,− 0.34) |

| Body fat (%) | −0.07(−0.12, −0.02) | −0.05(−0.15, 0.05) | −0.08(−0.17, 0.004) | −0.06(−0.12, 0.01) |

| Age | 0.02(−0.01,0.05) | −0.01(−0.08,0.05) | 0.01(−0.03,0.05) | 0.07(0.01,0.13) |

hourly mean ambient temperature recorded at nearest weather station (°C),

indicated on daily log completed by participants.

Personal heat exposure compared to nearby weather station datasets

Figures 1A and 1B show average daily temperatures from both the personal monitors (line) and the nearest weather station (circles), and indicate that weather station data overestimates average heat exposure, even for outdoor workers (Figure 1B). The data also suggests daily maximum temperature exposure from a nearby weather station may estimate daily maximum temperatures experienced in rural areas (Figure 1C), but maximum temperatures experienced by the urban participants were sometimes higher than those recorded at the nearest weather station (Figure 1D). Mixed effects model results suggest mean hourly weather station temperature is significantly associated with personal heat exposure across all groups, with the magnitude of the association larger among groundskeepers than for community members (Table 2). Across all participants, model results predict that heat exposure increases on average 0.37°C (95%CI 0.35, 0.39) for each 1°C increase in temperature recorded at the closest weather station. Based on these analyses, the weather stations overpredict average personal heat exposure; however for outdoor workers, the overestimation is slightly less (β 0.42°C (95%CI 0.39,0.46)).

Figure 1.

Average (A, B) and maximum (C, D) daily personal heat exposure measurements (lines) compared to temperatures recorded at the closest weather station (circles). Average daily temperature exposure in 30 urban community members (A). and 21 groundskeepers (B). Maximum daily temperature exposure in 30 rural community members (C) and 30 urban community members (D). Each participant wore the monitor for 7 days and the study was conducted over a 3 week period during the Summer of 2012 (X axis).

Hourly log data in which participants marked whether they were indoors or outdoors was used to evaluate factors associated with indoor and outdoor heat exposure in separate multivariable models. Of the 67 participants who reported sleep hours, participants reported being asleep approximately 27% of the total hours, which averages to approximately 7 hours per night (total hours includes 7 days and 6 nights). Urban community, rural community, and urban groundskeeper participants spent on average 71%, 73%, and 62% of their time indoors, respectively (Table 3). Groundskeepers spent more time outdoors (average of 31% of total hours) than urban or rural community members (19% and 18%, respectively) (Table 3), primarily due to increased work-related outdoor activities reported by groundskeepers; however, groundskeepers recorded fewer hours spent in outdoor recreation activities (Table 3). Community members reported more hours in transit compared to groundskeepers.

Table 3.

Average percentage ± standard deviation (number of individuals reporting for that category) of time spent indoors, outdoors, in transit, and in various microenvironments according to daily log of participants in rural SW Alabama and urban Birmingham, AL during Summer 2012

| Urban (Birmingham) N=28 | Rural (West Central AL) N=30 | Groundskeepers (Birmingham) N=19 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count of number of person hours recorded | 3244 | 4198 | 2470 |

| Average count of activity hours recorded on daily log per participant | 116±38(28) | 140±24 (30) | 129±29 (19) |

| Time spent indoors (%) | 71±15(28) | 73±11 (30) | 62±11 (19) |

| Time spent outdoors (%) | 19±14 (28) | 18±12 (30) | 31±8 (19) |

| Time in-transit (%) | 10±9 (28) | 9±6 (30) | 7±7 (19) |

| Microenvironments | |||

| Indoor time | |||

| Asleepa | 25±15 (24) | 29±9 (28) | 25±10 (15) |

| Homeb | 33±11 (28) | 34±14 (30) | 35±15 (19) |

| Work | 21±12(11) | 14±8 (9) | 5±6 (13) |

| Visiting a friend/ relative | 4±3 (12) | 3±2 (15) | 3±3 (5) |

| Church | 3±3 (10) | 4±3 (18) | 4±5 (4) |

| Store | 2±2(11) | 2±1 (11) | 2±1 (3) |

| Other | 5±5(24) | 4±3 (20) | 3±2 (14) |

| Outdoor time | |||

| Work | 12±9 (4) | 11±13 (5) | 25±8 (19) |

| Recreationc | 8±8 (26) | 7±6 (30) | 4±3 (17) |

| Visiting a friend/ relative | 4±3 (13) | 3±2 (17) | 4±2 (4) |

| Activitiesd | 5±4 (20) | 6±6 (25) | 4±3 (7) |

| Shop | 5±4 (24) | 3±3 (23) | 2±2 (5) |

| In-transit time | |||

| Vehicle | 11±9 (25) | 9±4 (27) | 7±5 (11) |

| Walking | 3±3 (6) | 1±1 (6) | 9 (1) |

| Work | 1 (1) | 7±11 (3) | 8±7 (6) |

Sleep is assumed to be indoors; not all participants reported awake vs. asleep time,

Home includes cooking, eating, tv, but excludes sleep,

Recreation includes sitting on the porch or in the yard,

Activities include exercising, gardening, and caring for animals or children

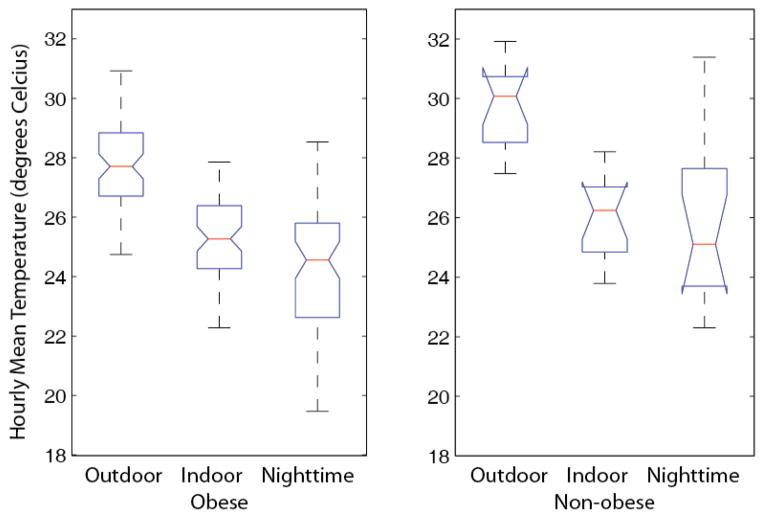

Weather station temperature was significantly associated with heat exposure across indoor, outdoor, and nighttime (between midnight and 5 am) personal exposure estimates, and the magnitude of the association was larger for the outdoor models than for the indoor and nighttime models (Table 4). Average outdoor temperatures experienced by groundskeepers (29.4°C) were higher than those experienced by urban and rural community members (28.5°C, 27.6°C, respectively) (Figure 2). Alternatively, average indoor temperatures experienced by urban community participants (25.4°C) and by urban groundskeepers (25.2°C) were slightly lower than those experienced by rural participants (25.8°C) (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Linear mixed model fixed effect predictors of personal outdoor, indoor and nighttime heat exposure (Alabama Summer 2012)

| Total heat exposure β (95% CI) | Outdoor heat exposure β (95% CI) | Indoor heat exposure β (95% CI) | Nighttime heat exposure β (95% CI) | light exposureb β (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weather stationa | 0.37 (0.35, 0.39) | 0.50(0.46, 0.55) | 0.35(0.33,0.36) | 0.25(0.20, 0.31) | 0.12(0.08,0.16) |

| Indoorsc | −2.02(−2.15, −1.89) | --- | --- | --- | −4.03(−4.36,−3.71) |

| Income > $20Kd | −0.90(−1.64,−0.15) | −0.49(−1.71, 0.73) | −1.19(−2.01,−0.37) | −1.45(−2.41,−0.50) | −0.02(−0.72,0.75) |

| Education> high school | 0.15 (−0.60, 0.91) | 0.35 (−0.88, 1.58) | 0.35 (−0.48, 1.18) | 0.45 (−0.52, 1.42) | −0.12(−0.87, 0.63) |

| Female | −0.37 (−1.61, 0.87) | −0.45(−2.47, 1.57) | −0.37(−1.73,0.98) | −0.61(−2.20, 0.98) | −0.23(−1.46,0.99) |

| Weekende | −0.22(−0.34, −0.10) | −0.47(−0.84,−0.11) | −0.10(−0.22, 0.02) | −0.01(−0.14, 0.13) | −0.37(−0.66,−0.07) |

| Body fat (%) | −0.08(−0.13,−0.03) | −0.06(−0.14, 0.01) | −0.08(−0.13, −0.03) | −0.07(−0.13,−0.01) | −0.05(−0.09,0.003) |

| Age | 0.02(−0.01, 0.05) | −0.05(−0.10,0.004) | 0.03(−0.004, 0.06) | 0.06(0.02,0.10) | −0.01(−0.04, 0.02) |

| Groundskeepers | −0.39(−1.47, 0.69) | 0.55(−1.19, 2.29) | −0.85(−2.04, 0.34) | −0.59(−1.97, 0.80) | 0.67(−0.40,1.74) |

| Rural environment | 0.58(−0.23, 1.39) | −0.50(−1.83, 0.83) | 0.84(−0.04, 1.73) | 0.75(−0.28, 1.79) | −0.22(−1.02, 0.58) |

hourly mean ambient temperature recorded at nearest weather station (°C),

hourly light exposure measured in lux (X 103),

participants marked being indoors on the hourly log,

participant reported a yearly income above $20,000.

The 2 weekend days versus the five week days participants wore the monitor.

Figure 2.

Mean hourly outdoor and indoor heat exposure in urban groundskeeper, urban community and rural community participants. The median (25th, 75th percentiles) of the hourly mean temperatures recorded per participant on the data logging monitor when the daily log was marked outdoor or indoor (Groundskeepers =19, Urban =28, Rural =30). Notches represent 95% confidence intervals on median.

Assessment of determinants of heat exposure

Additional covariates are also significantly associated with personal heat exposure. Participants who reported incomes above 20K per year had significantly lower heat exposure, as did participants with higher % body fat. When participants indicated that they were indoors on their daily logs, on average they experienced temperatures 2°C lower than if they had indicated that they were outdoors. When models were stratified by group, a higher outdoor/indoor differential (3.5°C) was seen within groundskeeper versus community member models, and within urban (2.0°C) versus rural (0.9°C) community models (Table 2).

Higher income and % body fat are significantly associated with lower indoor and nighttime heat exposure (Table 4). Higher BMI was also significantly associated with lower levels of heat exposure, and % body fat (but not BMI) remained significant in models with both BMI and % body fat (data not shown). When separating obese (BMI≥ 30) and non-obese participants, outdoor, indoor and nighttime heat exposure is decreased in obese versus non-obese participants (Figure 3). Outdoor heat exposure was lower on weekends and increasing age was significantly associated with higher nighttime heat exposure (Table 4). Being a groundskeeper or rural community member versus an urban community member was not significantly associated with total, outdoor, indoor or nighttime heat exposure.

Figure 3.

Outdoor, indoor, and nighttime heat exposure in obese (n=63) and non-obese (n=14) participants. The median (25th, 75th percentiles) of the hourly mean temperatures recorded per participant on the data logging monitor when the daily log was marked outdoor or indoor or during nighttime (12 AM to 5 AM) (Groundskeepers =19, Urban =28, Rural =30). Notches represent 95% confidence intervals on median.

Previous studies have shown the utility of light intensities as a quantifiable and objective measure of time outside versus indoors (Cleland et al., 2008; Cleland et al., 2010; Schmid et al., 2013). Figure 4 shows heightened light exposure captured from the monitor in groundskeepers compared to other community members on weekdays. Light intensity measurements were categorized based on four different cutoffs (200, 500, 1000200, 500, 2000 lux) from previous literature associating light intensity levels with time spent outdoors (Cleland et al., 2008; Cleland et al., 2010; Schmid et al., 2013). Spearman correlation coefficients calculated between daily log and monitor light intensity measurements were highly statistically significant, but correlation coefficients were relatively low (0.39, 0.41, 0.40, and 0.37 with increasing light intensity cutoffs), suggesting substantial additional variation in light intensity is likely explained by factors other than being indoors versus outdoors. Consistent with this, the regression fit was reduced in heat exposure models including light intensity as a potential covariate versus daily log as the covariate (AIC=55607 for model including daily log versus AIC=61223 with model including light intensity). Results of mixed effects regression models to evaluate factors associated with light exposure suggest higher ambient temperature as measured by the nearest weather station is significantly associated with higher light exposure and time spent indoors is significantly associated with lower levels of light exposure (Table 4). In addition, less overall light exposure was experienced on weekends versus weekdays.

Figure 4.

Average daily light exposure in urban (Birmingham, AL-Bham) and rural (Southwest AL) community members and Birmingham (Bham) groundskeepers over the 3 week study period. Shaded areas indicate weekends

Heat exposure models that additionally included monitor light measurements as a predictor were also evaluated since radiant heat, which is not incorporated into weather station air temperature measurements taken in the shade, would likely increase personal monitor temperature readings. Higher light exposure is associated with higher levels of personal heat exposure across all models (Supplemental Table 1). Interestingly, the magnitude of the association between heat exposure and light is larger within community member models versus the groundskeeper model while the magnitude of the negative association between daily log indoor indicator and heat exposure was larger in groundskeeper models versus community member models (Supplemental Table 1). This result may reflect the 6am – 2pm work-shift of groundskeepers, hence lower overall light exposure when outdoor heat is experienced.

DISCUSSION

The goal of the present study was to test a methodology for determining personal heat exposure in an occupationally exposed group, as well as in urban and rural populations having characteristics previously identified as vulnerability factors for heat related illness. We found that a temperature monitor clipped to the shoe provided a comfortable method for recording personal heat exposure. Ambient temperature recorded at the nearest weather station was significantly associated with personal heat exposure, particularly in groundskeepers who spent more of their total time outdoors. Factors associated with lower heat exposure include being indoors, reported annual income greater than $20,000, and higher % body fat. Analysis of outdoor heat exposure, indoor heat exposure, and nighttime heat exposure showed the income and % body fat effect was specific to indoor/nighttime heat exposure, suggesting modifications of the home thermal environment related to income and body composition play an important role in determining overall heat exposure. We found that total heat exposure was lower than what would be predicted by the nearest weather station, which is consistent with a previous study examining personal heat exposure in an elderly population in Baltimore (Basu and Samet, 2002).

Identification of populations vulnerable to heat-related health risks is critical for climate change adaptation planning and implementation. Several recent studies have highlighted the need for increasing our understanding of extreme heat events and adaptation strategies in rural versus urban areas (Huang, 2011; Knowlton et al., 2007; Reid et al., 2009). Previous studies have shown that extreme heat events result in excess mortality and morbidity in urban environments, particularly in the elderly and poor (Basu, 2009), and that land surface hotspots relate to land cover, minority populations, and lower socioeconomic status. The urban heat island effect increases daytime, and particularly nighttime temperatures in an urban center due to the increased absorption of heat via buildings and pavement (Smargiassi et al., 2009). Quinn et al. (2014) quantified the association between outdoor temperature/humidity and indoor temperature/humidity recorded in New York apartments during summer months and predicted between 1.7% and 16% of apartments would exceed dangerous heat levels during a prolonged heat wave such as the one experienced in 2006 (Quinn et al., 2014).

Many urban centers now implement heat wave alert systems and set up air-conditioned centers, which has been associated with reduced heat-related mortality (Albrecht, 2010), yet these prevention strategies are rarely implemented in rural communities. Although not as well studied, rural communities may have unique vulnerabilities to extreme heat events as a recent study in Germany suggests (Tomlinson et al., 2011). Projections of heat-related health impacts in New York City and the surrounding areas suggest rural areas may experience a greater percent increase in heat-related mortality (Knowlton et al., 2007). For example, increased travel time to health care facilities may lead to more severe outcomes (Gabriel and Endlicher, 2011). Occupational risks may be heightened in rural communities engaged primarily in outdoor occupations (Nag, 2010).

Limitations of the current study include potential exposure misclassification introduced by the different time resolutions when comparing outdoor and indoor heat exposures determined by using activity logs and personal monitor measurements. For example, participants may have checked outdoors even when less than 50% of the hour was spent outdoors or vice versa, whereas monitor data was recorded each minute and averaged over each hour. Other potential issues include differing distances from the nearest weather station and classifying in-transit vehicle time as indoor as temperatures experienced were similar to those experienced during indoor time. In addition, some participants marked outside when they were out of their residence, but often in stores, restaurants, banks, etc. (Table 2). Personal monitors recorded total heat exposure, which included radiant heat, likely making comparisons with weather station datasets less reliable, particularly on sunny days. Also, bias introduced from participants’ efforts to please researchers, incomplete logs, and forgetting or misplacing monitors cannot be ruled out. The present study did not capture skin or core body temperature to assess how ambient temperatures are associated with physiological changes, since our goal was the measurement of personal heat exposure throughout the day across different populations.

Each participant wore their monitor for 7 days, therefore weather variations across these 3 weeks may have influenced heat exposure via weather specific behaviors, i.e. if it was raining or particularly hot participants may have chosen to stay indoors. For example, Bosdriesz et al (2012) examined macro-level influencers on physical activity in 38 countries and found higher temperatures were associated with less physical activity (Bosdriesz et al., 2012). Horanont et al (2013) used GPS tracers with mobile phones to examine activity patterns of public places visited, duration of visit, and deviations from the normal patterns correlated with weather events like rain, wind, and cold (Horanont et al., 2013). In a future study, utilization of personal monitors with GPS capability may help to tease apart how specific weather patterns affect behavior and ultimately heat exposure.

In conclusion, we have reported a feasible method for measuring personal heat exposure. Our results suggest physical characteristics such as % body fat and age, as well as socioeconomic characteristics may be important determinants of heat exposure. Results from the present analysis suggest future work examining adverse health effects related to heat waves may need to address exposure misclassification by more explicitly accounting for differences in when time is spent outdoors and differences in indoor thermal environments. Use of personal monitors is a feasible method to conduct such future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES: We gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Institutes of Health (NIEHS R21 ES020205), a grant from the University of Alabama’s (UAB) Deep South Occupational Health and Safety Center (NIOSH T42OH008436-08), UAB’s Center for the Study of Community Health (CDC coop. agreement U48/DP001915), and UAB Nutrition and Obesity Research Center (NIDDK P30DK056336) . MCB and MES received support from the UAB CaRES program (R25CA76023 from the National Cancer Institute).

This study was reviewed and approved by the UAB Institutional Review Board (X120513012 and X120217008).

We gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Institutes of Health (NIEHS R21 ES020205), a grant from the University of Alabama’s (UAB) Deep South Occupational Health and Safety Center (NIOSH T42OH008436-08), UAB’s Center for the Study of Community Health (CDC coop. agreement U48/DP001915), and UAB Nutrition and Obesity Research Center (NIDDK P30DK056336) . MCB and MES received support from the UAB CaRES program (R25CA76023 from the National Cancer Institute). Thanks to Sheila Tyson and Nakeia Pullman (Friends of West End), and Sheryl Threadgill-Mathews and Ethel Johnson (West Central Alabama Community Health Improvement League), Dzigbodi Doke (UAB School of Public Health) and City of Birmingham Public Works Department, for their aid in recruitment and implementation of the research.

References

- ADPH. Heat-related illnesses and death in Alabama. 2012 Sep 29; [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht U. Circadian clocks in mood-related behaviors. Ann Med. 2010;42:241–51. doi: 10.3109/07853891003677432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GB, Bell ML. Heat waves in the United States: mortality risk during heat waves and effect modification by heat wave characteristics in 43 U.S. communities. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:210–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu R. High ambient temperature and mortality: a review of epidemiologic studies from 2001 to 2008. Environ Health. 2009;8:40. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu R, Samet JM. An exposure assessment study of ambient heat exposure in an elderly population in Baltimore, Maryland. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:1219–24. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosdriesz JR, et al. The influence of the macro-environment on physical activity: a multilevel analysis of 38 countries worldwide. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:110. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd GM. Wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT)--its history and its limitations. J Sci Med Sport. 2008;11:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland V, et al. A prospective examination of children's time spent outdoors, objectively measured physical activity and overweight. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1685–93. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland V, et al. Predictors of time spent outdoors among children: 5-year longitudinal findings. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:400–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.087460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel KM, Endlicher WR. Urban and rural mortality rates during heat waves in Berlin and Brandenburg, Germany. Environ Pollut. 2011;159:2044–50. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher DVM, Sepúlveda D, Pierson RN, Harris T, Heymsfield SB. How useful is body mass index for comparison of body fatness across age, sex, and ethnic groups? Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:228–39. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horanont T, et al. Weather effects on the patterns of people's everyday activities: a study using GPS traces of mobile phone users. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Zhou W, Cadenasso ML. Is everyone hot in the city? Spatial patttern of land surface temperatures, land cover and neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics in Baltimore, Md. J Environ Manage. 2011;92:1753–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton K, et al. Projecting heat-related mortality impacts under a changing climate in the New York City region. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2028–34. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton K, et al. The 2006 California heat wave: impacts on hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:61–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioy PJ, et al. Personal and ambient exposures to air toxics in Camden, New Jersey. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2011:3–127. discussion 129–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag PK. Extreme heat events--a community calamity. Ind Health. 2010;48:131–3. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.48.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe RS, et al. Exposure to natural cold and heat: hypothermia and hyperthermia Medicare claims, United States, 2004–2005. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:e11–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng RD, et al. Toward a quantitative estimate of future heat wave mortality under global climate change. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:701–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn A, et al. Predicting indoor heat exposure risk during extreme heat events. Sci Total Environ. 2014;490:686–93. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid CE, et al. Evaluation of a heat vulnerability index on abnormally hot days: an environmental public health tracking study. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:715–20. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid CE, et al. Mapping community determinants of heat vulnerability. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1730–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhea S, Ising A, Fleischauer AT, Deyneka L, Vaughan-Batten H, Waller A. Using near realtime morbidity data to identify heat-related illness prevention strategies in North Carolina. J Community Health. 2012;37:495–500. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9469-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid KL, et al. Assessment of daily light and ultraviolet exposure in young adults. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:148–55. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31827cda5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smargiassi A, et al. Variation of daily warm season mortality as a function of micro-urban heat islands. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:659–64. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.078147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson CJ, et al. Including the urban heat island in spatial heat health risk assessment strategies: a case study for Birmingham, UK. Int J Health Geogr. 2011;10:42. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-10-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, et al. Ambient temperature and morbidity: a review of epidemiological evidence. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:19–28. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, et al. Geostatistical exploration of spatial variation of summertime temperatures in the Detroit metropolitan region. Environ Res. 2011;111:1046–53. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.