SUMMARY

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) occur within chromatin-modulating factors; however, little is known about how these variants within the coding sequence impact cancer progression or treatment. Therefore, there is a need to establish their biochemical and/or molecular contribution, their use in sub-classifying patients and their impact on therapeutic response. In this report, we demonstrate that coding SNP-A482 within the lysine tri-demethylase KDM4A/JMJD2A has different allelic frequencies across ethnic populations, associates with differential outcome in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients and promotes KDM4A protein turnover. Using an unbiased drug screen against 87 preclinical and clinical compounds, we demonstrate that homozygous SNP-482 cells have increased mTOR inhibitor sensitivity. mTOR inhibitors significantly reduce SNP-A482 protein levels, which parallels the increased drug sensitivity observed with KDM4A depletion. Our data emphasize the importance of using variant status as candidate biomarkers and highlight the importance of studying SNPs in chromatin modifiers to achieve better targeted therapy.

User-defined key words: KDM4A, mTOR, epigenetic, demethylase, lung cancer, polymorphism

INTRODUCTION

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), the most common type of genetic differences in humans, are defined as a single base pair difference in the DNA with the least abundant allele present in at least 1% of the population (1). Germline SNPs can be associated with the risk and onset of diseases, including cancer (2). Such variants can also predict disease outcome and/or response to treatment, even without their direct association with the disorder (3). SNPs located in coding regions and regulatory gene elements are more likely to affect protein levels and function, and non-synonymous SNPs presenting a low degree of differentiation in the population are significantly more frequent in genes known to modulate diseases. Thus, these SNPs likely result in deleterious protein function and are of interest for medical research (4).

To date, little knowledge exists about how coding SNPs alter the function of chromatin modifying enzymes (5). Importantly, emerging data on somatic mutations in cancer has identified these enzymes as critical cancer genes (5). For this reason, germline variants in these enzymes are likely determinants in disease susceptibility and therapeutic drug responses. Consistent with this notion, a coding SNP in the lysine demethylase KDM4C has recently been linked to breast cancer outcome (6). Therefore, understanding the molecular and biochemical roles of these enzymes and factoring in the impact SNPs have on their biology will be necessary to identify important disease biomarkers and provide insights into novel therapies or drug combinations.

In the present study, we describe the cellular and biochemical impact of a SNP in the coding region of the lysine demethylase KDM4A. KDM4A is a JmjC domain-containing lysine demethylase targeting H3K9me3, H3K36me3 and H1.4K26me3 (7). Ubiquitination of KDM4A is a major regulatory mechanism for controlling the identified functions of this protein (8, 9). Consistent with the need to modulate KDM4A levels, tumors have been shown to have both gain and loss of KDM4A alleles. While overexpression and KDM4A copy gain have been shown to impact nuclear functions such as site-specific copy regulation (10), defined roles for KDM4A loss or decreased expression need additional exploration.

We have identified a coding SNP within KDM4A that results in the conversion of the glutamic acid at position 482 to alanine (E482A; referred to as SNP-A482). Consistent with this SNP having important biological associations, we observe differential distribution across ethnic populations and poor outcome in homozygous SNP-A482 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Furthermore, we demonstrate that SNP-A482 increases ubiquitination and protein turnover by increasing the interaction with the SCF complex. An unbiased drug sensitivity screen of cells homozygous for SNP-A482 establishes an unprecedented link between KDM4A and inhibition of the mTOR pathway. In fact, mTOR inhibitors significantly reduce SNP-A482 protein levels when compared to wild type KDM4A. Consistent with this observation, reduced KDM4A protein levels increase mTOR inhibitor sensitivity. Taken together, these findings report the first coding germline variant in a lysine demethylase that impacts chemotherapeutic response, which identifies KDM4A as a potential candidate biomarker for mTOR inhibitor therapy.

RESULTS

SNP-A482 is associated with worse outcome in NSCLC patients

Our laboratory has recently demonstrated that the lysine demethylase KDM4A is copy gained and lost in various cancers (10). Consistent with our studies, other groups have established that KDM4A protein levels are linked to cell proliferation, metastatic potential and patient outcome for lung and bladder cancers (11, 12). Therefore, we evaluated whether there are genetic factors that could influence KDM4A protein levels and function. Specifically, we evaluated non-synonymous coding single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in KDM4A since they are more likely to alter protein function due to a change in an amino acid sequence (5). Our evaluation of the dbSNP database identified only one coding SNP for KDM4A with reported allele frequencies.

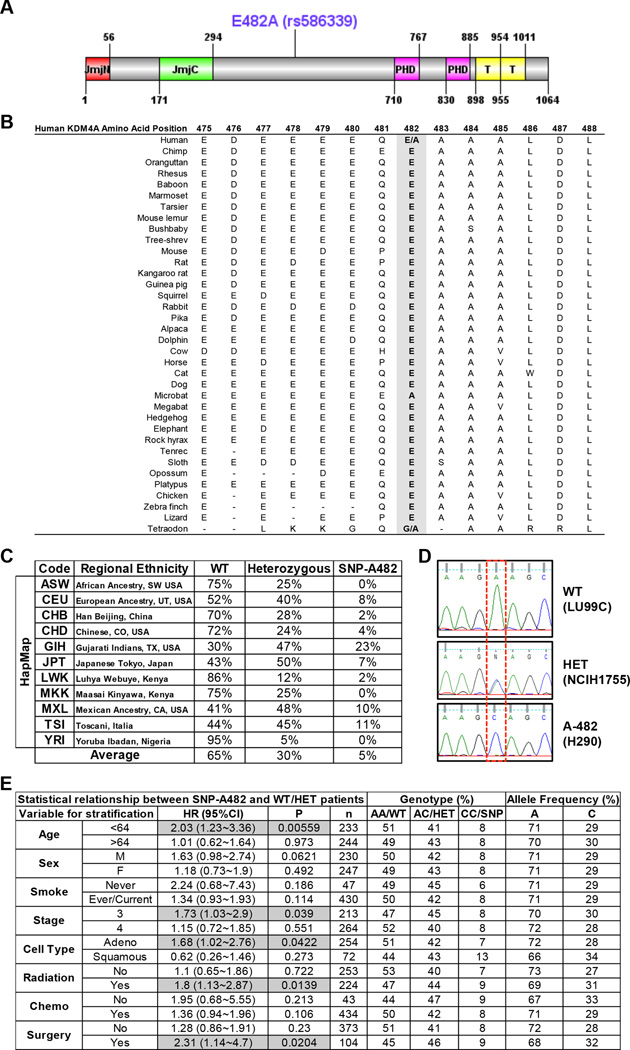

KDM4A SNP rs586339A>C has a minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.238. The rs586339 SNP results in a single base substitution that leads to an amino acid substitution: E482 (GAA) to A482 (GCA). Therefore, we refer to this germline variant as SNP-A482 (Figure 1A). We identified adenine “A” encoding E482 to be the major allele [referred to as wild type (WT) throughout the text and figures] for two reasons: 1) this amino acid is conserved across species (Figure 1B); and 2) both dbSNP database and HapMap analysis reported “A” as the major allele. Upon evaluating the HapMap project, we observed different allelic frequencies across various ethnic populations (Figure 1C) (13), highlighting an ethnic diversity for this SNP. The average HapMap allelic frequency across all evaluated populations is 65% for homozygote for the major allele (WT), 30% for heterozygote, and 5% for homozygote for the minor allele (SNP-A482) (Figure 1C). The presence of the SNP in cell lines was confirmed using Sanger sequencing (Figure 1D) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (not shown).

Figure 1. KDM4A SNP-A482 (rs586339) correlates with worse outcome in NSCLC patients.

(A) Schematic of the human KDM4A protein is shown with both the protein domains and the position of the coding SNP rs586339 (E482A). Jumonji (JmjN and JmjC), PHD and Tudor (T) domains are represented. (B) E482 is the conserved allele. The alignment of sequence surrounding E482A is shown for multiple species. (C) HapMap frequencies for rs586339 are presented (August 2010 HapMap public release #28) (13). ASW- African Ancestry in SW USA (n=57); CEU- U.S. Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe (n=113); CHB- Han Chinese in Beijing, China (n=135); CHD- Chinese in Metropolitan Denver, CO, USA (n=109); GIH- Gujarati Indians in Houston, TX, USA (n=99); JPT- Japanese in Tokyo, Japan (n=113); LWK- Luhya in Webuye, Kenya (n=110); MKK- Maasai in Kinyawa, Kenya (n=155); MXL- Mexican Ancestry in Los Angeles, CA, USA (n=58); TSI- Toscani in Italia (n=102); YRI- Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria (n=147). (D) Representative KDM4A sequencing plots from three different lung cancer cell lines- homozygote wild type (WT, GAA:GAA), heterozygote (HET, GAA:GCA) and homozygote SNP (A-482, GCA:GCA). (E) KDM4A SNP-A482 stratification for late stage NSCLC patients. HR represents the hazard ratio, 95%CI the 95% confidence interval, p the p value, n the number of patients in each category, AA the genotype for homozygote wild-type (E482), AC for heterozygote, CC for homozygote SNP (A482). Gray boxes highlight the parameters with significance, including the data in panels B-F. Frequency comparisons were tested using the chi-square test, and Hazard Ratios were calculated using a Cox model. Also see supplementary Figure S1.

In order to further establish whether SNP-A482 had any disease associations, we evaluated a well-characterized cohort of NSCLC patients (14, 15) and determined whether homozygous KDM4A SNP-A482 NSCLC patients were associated with differential outcome based on various clinical parameters. Interestingly, NSCLC and non-NSCLC cohorts exhibited comparable allelic frequency, suggesting that there is no selection against the A482 allele in NSCLC patients (Figure S1A). Patients that were homozygous for KDM4A SNP-A482 experienced an overall worse outcome, with borderline statistical significance (p=0.055), and had significantly worse outcomes for certain late stage patient parameters (p<0.05, Figures 1E and S1B–F).

In order to further evaluate the predictive ability of SNP-A482 as a biomarker of survival and outcome, we performed time-dependent receiver operator characteristics curve (ROC) analyses on five subgroups of NSCLC patients (age<64, adenocarcinoma, stage 3, with radiation therapy, and with surgery). In each subgroup, we compared the area under the curve (AUC) of the model with SNP-A482 and clinical information (age, sex, smoking status) to the model with clinical information only. In general, the predictive model with SNP-A482 had a slightly better performance, with the caveat being the low heritability results in the predictive model being more limited (Figure S1G) (16). Therefore, these data do not necessarily support the SNP-A482 serving as a biomarker alone; however, future studies containing larger sample sizes will help with the assessment of such a predictive model. These data do however highlight a disease association for SNP-A482 and support a rationale for exploring the impact SNP-A482 has on KDM4A.

SNP-A482 results in increased ubiquitination and turnover of KDM4A

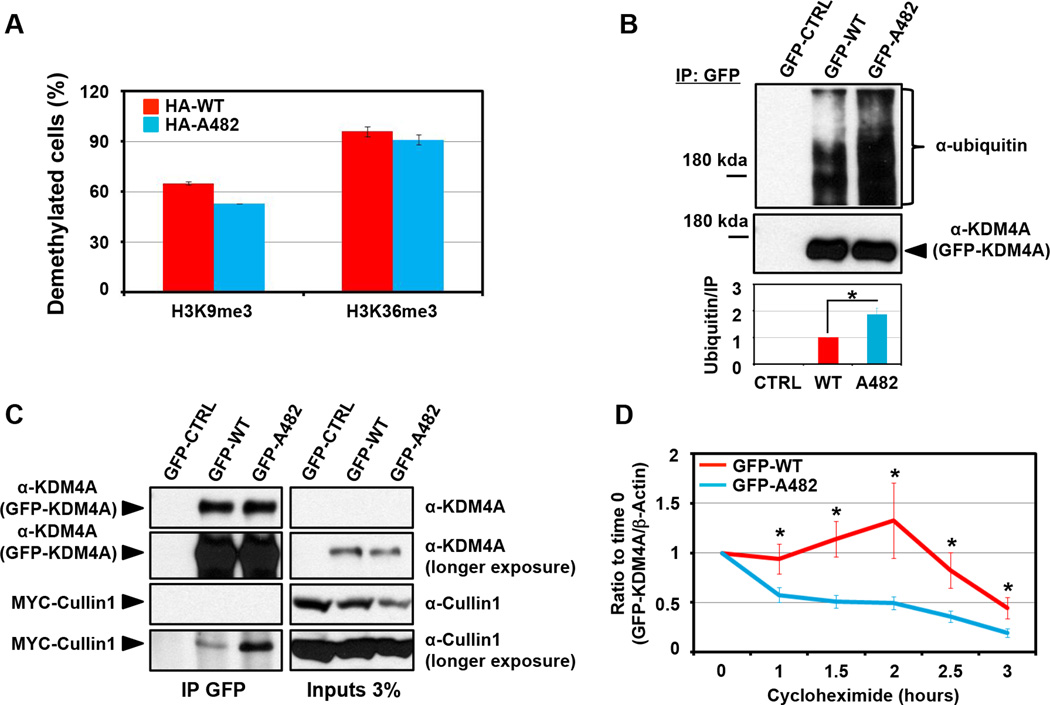

We wanted to determine if there was a biochemical difference between KDM4A WT and KDM4A SNP-A482. Since KDM4A is a histone demethylase (7), we determined whether SNP-A482 had altered catalytic activity when compared to WT KDM4A in vivo. RPE cells transfected with either HA-tagged WT KDM4A or SNP-A482 had similar H3K9me3 and H3K36me3 catalytic activities (Figure 2A). However, SNP-A482 had an increase in higher molecular weight products when evaluated by western blot (data not shown), which was demonstrated to be ubiquitination by immunoblotting for ubiquitin after conducting denaturing GFP immunoprecipitation (IP) (Figure 2B). Multiple replicate experiments indicated that there was a two-fold increase in KDM4A SNP-A482 ubiquitination when the IP was normalized and compared to wild type KDM4A (Figure 2B, lower panel; p=0.01).

Figure 2. SNP-A482 promotes KDM4A ubiquitination and turnover.

(A) KDM4A WT and SNP-A482 comparably demethylate H3K36me3 and H3K9me3. 3xHA-KDM4A WT and 3xHA-KDM4A SNP-A482 were transfected into RPE cells, fixed and stained with the indicated antibodies. The graph represents an average of two experiments. At least fifty cells were scored per experiment. (B) KDM4A SNP-A482 exhibits a two-fold greater ubiquitination than KDM4A WT. GFP-KDM4A WT and GFP-KDM4A SNP-A482 were transfected into HEK 293T cells prior to immunoprecipitation with a GFP antibody under denaturing conditions and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Quantification was performed with ImageJ. The graph represents an average of five independent experiments that show the ratio of ubiquitin signal to the amount of immunoprecipitated protein. (C) GFP- A482 co-immunoprecipitates more MYC-Cullin1 than GFP-WT KDM4A. GFP-WT and GFP- A482 were transfected into HEK 293T cells before being immunoprecipitated with a GFP antibody and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (D) GFP- A482 has a shorter half-life than GFP-WT KDM4A. HEK 293T cells overexpressing GFP-WT or GFP-A482 were treated with cycloheximide and western blotted. The y axis represents the ratio of GFP-tagged KDM4A relative to time 0, which was normalized to β-actin. The average of 16 independent experiments is shown. All error bars represent the SEM. P values were determined by a two-tailed student’s t test; * represents p<0.05.

We and others have previously demonstrated that KDM4A is ubiquitinated by the SCF complex containing the E3 ligase Cullin1 (8, 9). Consistent with increased ubiquitination of SNP-A482, KDM4A SNP-A482 co-immunoprecipitated more MYC-Cullin1, which reflects an increased association with the SCF complex (Figure 2C). In addition, KDM4A SNP-A482 exhibited a shorter half-life when compared to KDM4A WT (1h38min versus 2h58min, respectively; Figure 2D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that SNP-A482 results in altered KDM4A ubiquitination and contributes to changes in KDM4A protein stability.

KDM4A SNP-A482 alters chemotherapeutic sensitivity in lung cancer cell lines

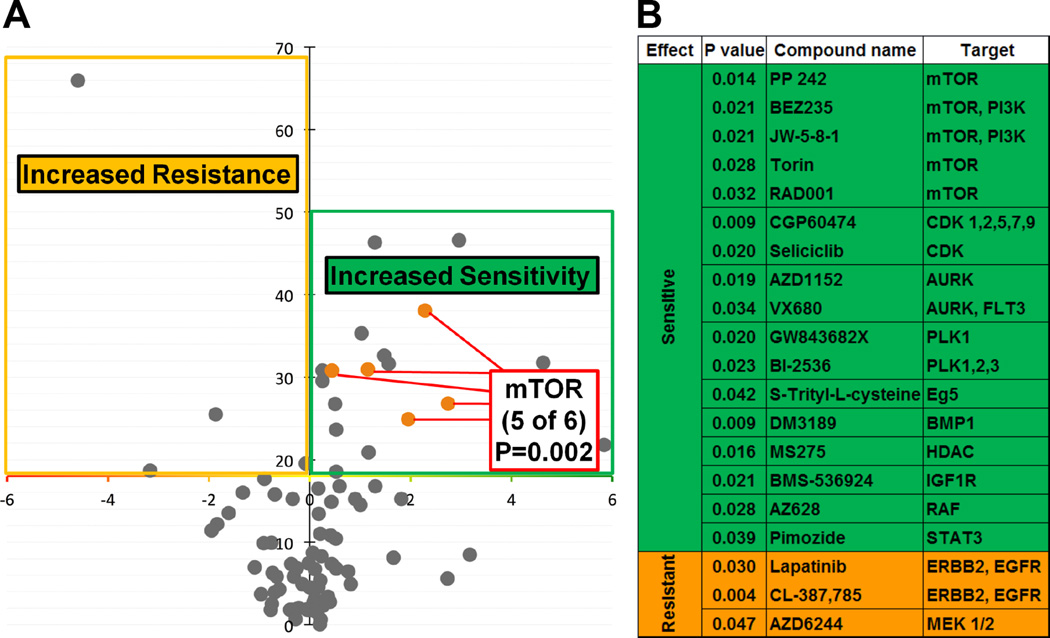

In order to determine whether there are differential roles between WT and SNP-A482, we first assessed the impact of SNP-A482 on KDM4A-dependent phenotypes. Similar to WT KDM4A, SNP-A482 overexpression resulted in faster progression through S phase and promoted site-specific copy gains (data not shown). In a further attempt to resolve differences between the wild type and SNP-A482 containing cells, we conducted an unbiased association study between 86 genotyped lung cancer cell lines (Figure S2A) and their corresponding drug sensitivities. These cell lines were treated with 87 preclinical and clinical compounds at three different drug concentrations (Table S1). We compared the cell lines homozygous for the minor allele to the cell lines heterozygous and homozygous for the major allele. The results of the analysis are summarized as a volcano plot representing the statistical significance (inverted Y axis) versus the effect of KDM4A SNP-A482 on drug sensitivity (Figure 3A). KDM4A SNP-A482 was significantly associated with altered drug response to 20 compounds: 17 compounds (green) were associated with increased drug sensitivity and three compounds (orange) were associated with increased drug resistance (Figures 3A, B). These compounds were then classified based on reported literature and known targets (Figure 3B). The most striking enrichment was observed for mTOR inhibitors. Lung cancer cells homozygous for KDM4A SNP-A482 had increased sensitivity to five different mTOR/PI3K inhibitors (p=0.002; Figures 3A, B). Figure S2A shows that the different mTOR inhibitors have a consistent effect across each cell line used in our screen. This consistency is illustrated by looking at the relative sensitivity to each inhibitor obtained by median centering of the viability ratio values. Importantly, 10 of the 17 compounds that were associated with increased sensitivity in SNP-A482 homozygous cell lines are involved in targeting pathways related to mTOR/PI3K signaling (Figure S2B).

Figure 3. KDM4A SNP-A482 impacts cellular sensitivity to specific drugs.

(A) Volcano plot representing statistical significance (inverted Y axis) versus the effect of KDM4A SNP-A482 on drug sensitivity. Compounds above the X axis are statistically significant (p<0.05). Eighty seven cell lines and eighty eight compounds were used; the statistical significance of the enrichment for mTOR inhibitors in the group of drugs linked to the SNP status is indicated (p=0.002). (B) A list of compounds with statistically different sensitivity in (A), their associated targets and corresponding p values are shown. p values were calculated with Fisher’s exact test. Also see supplementary Figure S2 and supplementary Table 1.

In order to further establish the specificity of the relationship between KDM4A SNP-A482 and mTOR inhibition, we examined the relationship between drug sensitivity and other SNPs within KDM4A (Figure S2C, D). We genotyped the lung cancer cell lines used in the initial screen for two additional KDM4A SNPs. We chose to study the non-coding SNP rs517191, which lacks significant association with overall NSCLC patient outcome, and the non-coding SNP rs6429632, for which the significant outcome associations in homozygous late stage patients were not identical to that of KDM4A SNP-A482 [rs586339] (Figure S2D). Interestingly, only cell lines homozygous for KDM4A SNP-A482 and not rs517191 or rs6429632 exhibited increased sensitivity to the majority of mTOR inhibitors compared to the cells heterozygous and homozygous for the major alleles (Figure S2E). These data suggest that the mTOR pathway directly or indirectly associates with SNP-A482.

mTOR inhibition reduces KDM4A protein levels

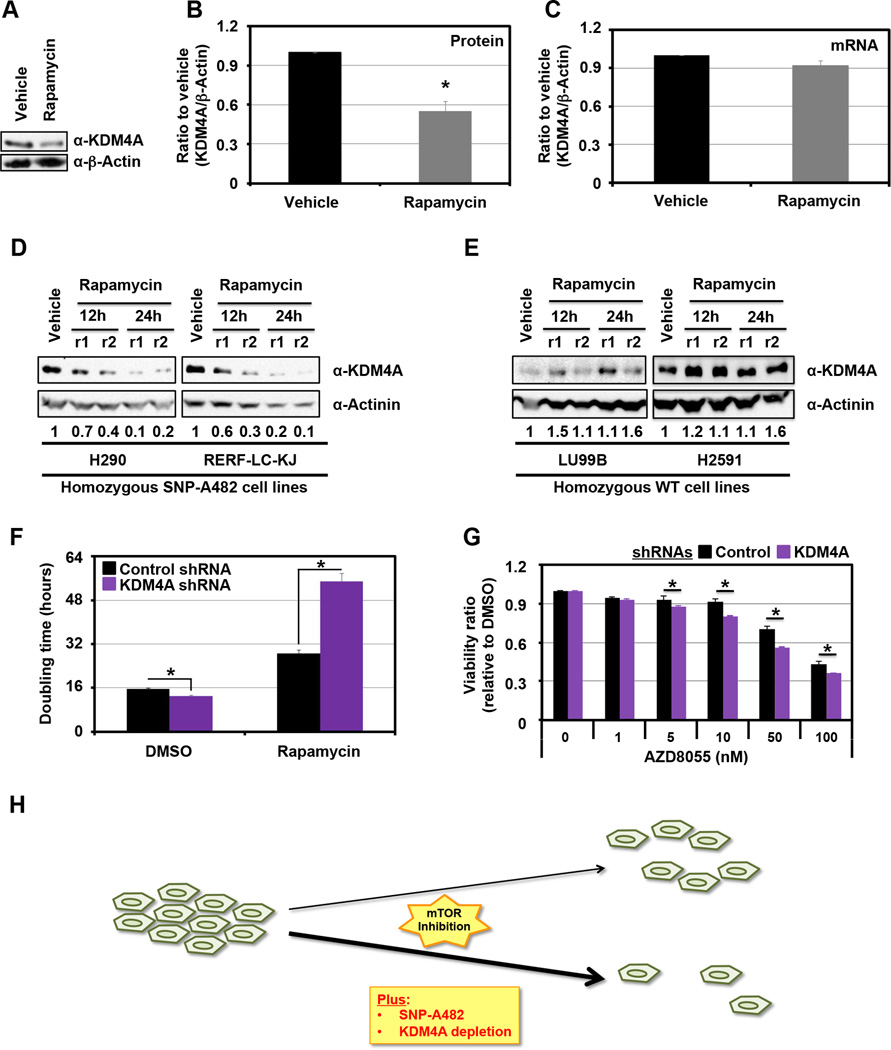

Due to the enrichment for mTOR inhibitor sensitivity in relation to SNP-A482, we further evaluated the biochemical relationship between KDM4A SNP-A482 and this class of compounds. Based on the observation that KDM4A SNP-A482 increases KDM4A ubiquitination and turnover (Figure 2), we determined the impact that mTOR inhibition had on endogenous KDM4A levels in a heterozygous cell line (Figures 4A–C). Consistent with mTOR inhibition affecting mRNA translation (17, 18), endogenous KDM4A protein levels were reduced during Rapamycin treatment (Figure 4A, B), whereas RNA levels were unchanged (Figure 4C). Since KDM4A SNP-A482 has a faster half-life compared to KDM4A WT (Figure 2D), we hypothesized that SNP-A482 protein levels would be lower than KDM4A WT protein levels in the presence of mTOR inhibitors. To test this hypothesis, we treated two cell lines of each of the KDM4A homozygous genotypes [i.e., homozygote SNP-A482 (Figure 4D) or WT (Figure 4E)] with Rapamycin and analyzed endogenous KDM4A levels over time (Figure 4D, E and S3A). Indeed, H290 and RERF-LC-KJ cells, which are homozygous for KDM4A SNP-A482, exhibited reduced endogenous KDM4A protein levels upon mTOR inhibition (Figure 4D); whereas, LU99B and H2591 cells, which are homozygous for KDM4A WT, did not exhibit this phenotype (Figure 4E and Figure S3A, compare blue line to red line, p=0.034, significance for overall difference). In order to rule out the contribution of different genetic backgrounds in these cancer cell lines, we performed the same experiments within a single cell line that transiently overexpressed GFP-KDM4A WT or GFP-KDM4A SNP-A482. We observed the same phenotype in these cells (Figure S3B, compare blue line to red line, respectively; p=0.003, significance for overall difference). Taken together, these data suggest that mTOR inhibition leads to a more pronounced decrease in SNP-A482 protein levels than WT KDM4A.

Figure 4. KDM4A levels impact cellular sensitivity to mTOR inhibitors.

(A) KDM4A protein levels decrease upon Rapamycin treatment. HEK 293T cells were treated with 100ng/ml of Rapamycin for 24h. (B) Graphical representation of an average of three independent experiments from (A). (C) KDM4A RNA levels are stable upon Rapamycin treatment. HEK 293T cells were treated with 100ng/ml of Rapamycin for 24h before RNA was harvested. An average of three independent quantitative RT-PCR experiments is represented. (D-E) Endogenous KDM4A SNP-A482 protein levels decrease more upon Rapamycin treatment than WT KDM4A. Lung cell lines homozygous for KDM4A SNP-A482 (D; H290 and RERF-LC-KJ) or WT (E; LU99B and H2591) were treated with 100ng/ml of Rapamycin for 24h. Independent replicates (r1 and r2) are shown per time point. Quantification was performed with ImageJ. The numbers under the blots represent the ratio of the amount of KDM4A to the amount of Actinin, normalized to vehicle. (F) HEK 293T cells transfected with three different shRNAs directed against KDM4A have increased sensitivity to Rapamycin when compared to control vector transfected cells. HEK 293T cells were seeded 24h after transfection and treated with 100ng/ml of Rapamycin 24h after seeding. The graphs represent the doubling time between 5h and 35h after Rapamycin treatment. An average of three independent experiments is represented. (G) HEK 293T cells transfected with shRNA 4A.6 are more sensitive to AZD8055 than cells transfected with the control vector. Cells were seeded 24h after the second shRNA transfection and were then treated with the indicated drugs and associated concentrations 24h later. 48h after treatment, samples were analyzed by MTT assay. The assays were normalized to a sample collected and assayed at the treatment time. The Y axis represents the viability ratio relative to DMSO. The average of three independent experiments is represented. (H) Model. KDM4A depletion of SNP-A482 enhanced the sensitivity to mTOR inhibitors. All error bars represent the SEM. p values were determined by a two-tailed student’s t test; * represents p<0.05. Also see supplementary Figure S3.

Reduced KDM4A protein levels enhances cell sensitivity to mTOR inhibitors

We hypothesized that the increased mTOR inhibitor sensitivity observed for KDM4A SNP-A482 cell lines was due at least in part to the stronger reduction in KDM4A levels upon mTOR inhibitor treatment. To test this hypothesis, KDM4A was depleted from cells using shRNAs, and cell proliferation was monitored during Rapamycin treatment. Indeed, shRNAs directed against KDM4A further extended the already increased doubling time observed after Rapamycin treatment (Figures 4F and S3C). In order to confirm this result, cells were depleted of KDM4A prior to treatment with the ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitor AZD8055 for 48h before cell proliferation and viability was assessed using MTT assays. Independent experiments demonstrated an increased sensitivity to mTOR inhibition upon KDM4A knock-down (Figures 4G and S3D and data not shown). Consistent with these observations, we most recently demonstrated that KDM4A interacts with translation initiation factors and modulates protein synthesis, which was enhanced with mTOR inhibition (19). Taken together, these data suggest that SNP-A482 status and KDM4A levels play an important role in sensitizing cells to mTOR inhibitors (Figure 4H).

DISCUSSION

Personalized therapy is becoming more common in cancer treatment (20). For example, SNP status can be used to assess risk of disease or predict outcome and/or response to treatment and may also have a place in the sub-classification of patients for optimal treatment delivery (2, 3). The ultimate goal of this approach is to utilize the genetic/biochemical properties of a target in certain cancer types and/or individuals to provide more effective treatment strategies. In order to achieve this goal, genetic and biochemical properties need to be established for genetic alterations linked to diseases.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report that identifies a coding SNP within a chromatin modifier with links to NSCLC outcome and drug response. These data are particularly important given that 85% of lung cancers are NSCLC, with 70% presenting as advanced disease, i.e. locally advanced IIIB or metastatic disease IV, and are not considered to be curable. The five-year survival rates for these advanced NSCLC stages are 7% and 2%, respectively. Moreover, mTOR and PI3K inhibitors are being used to treat NSCLC (20, 21). Testing for multiple biomarkers in order to apply more targeted therapies is already considered to be the standard of care for lung cancer (20). Therefore, our study provides another possible option to stratify and possibly treat sub-groups of NSCLC patients.

We report that KDM4A SNP-A482 is linked to worse outcome in NSCLC patients; however, the analyses suggest this single variable is not a sufficient biomarker. Future studies with larger datasets are required to better clarify this possibility. The association with worse outcome in our data could reveal the fact that KDM4A levels or altered function result in a benefit to certain tumors. For example, tumors with lower KDM4A protein levels have been shown to predict significantly worse overall survival (12). Interestingly, 20% of tumors assessed from the TCGA present a copy loss of KDM4A, which correlated with a decrease in KDM4A RNA levels (10). Furthermore, reduced KDM4A protein levels are observed with cancer progression and metastasis (12). Therefore, tumors with SNP-A482 could possess an ability to more effectively reduce KDM4A levels. Another possibility is that since SNP-A482 is germline transmitted, the cells throughout the body could be the basis for the associated worse outcome. For example, patients could have impaired immune responses, increased toxicity to therapies or altered tissue repair. For these reasons, analyses of additional data sets as well as prospective genetic studies evaluating the response of tumors and the individual to treatment as well as noted toxicities will be necessary to fully understand the impact of the SNP on patient outcome.

Since SNP-A482 and KDM4A depletion increased mTOR inhibitor sensitivity, we suspect that other cancer sub-types will also be good candidates for this genetic or chemical based targeting in the future (Figure 4H). For example, the mTOR inhibitor Temsirolimus (CCI-779) is used for advanced refractory renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (22). A phase II clinical trial presented an objective response rate for only 7% of RCC patients (22). Interestingly, this proportion is similar to that observed for individuals homozygous for the rs586339 minor allele (KDM4A SNP-A482) (Figures 1C and S1A). It would be interesting to determine whether response correlates with KDM4A SNP-A482 status in RCC.

In conclusion, we have now uncovered a genetic feature in KDM4A (SNP-A482) that could allow patient stratification and more effective treatment options for these individuals. Since the KDM4A allele is lost in certain tumors (10), these tumors could also be ideal candidates for mTOR-related chemotherapies. Overall, the current study highlights the fact that biochemical and cellular analyses of somatic and polymorphic variants within chromatin-modifying enzymes can identify associated signaling pathways and establish optimal chemotherapeutic targets in the future.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell culture and drug treatments

For tissue culture and generation of stable cell lines see (10). HEK 293T and RPE cells have been obtained from ATCC, no authentication has been done by the authors. All lung cell lines were sourced from commercial vendors. To exclude cross-contaminated or synonymous lines, a panel of 92 SNPs was profiled for each cell line (Sequenom) and a pairwise comparison score was calculated. In addition, we performed short tandem repeat (STR) analysis (AmpFlSTR Identifiler, Applied Biosystems) and matched this to an existing STR profile generated by the providing repository. After initial expansion and STR analysis each stock vial of cells was not propagated for more than 2 months. Rapamycin (LC Laboratories) and AZD8055 (Selleckchem) were used at indicated concentrations. Cycloheximide and MG132 were used as described in (8).

Plasmids, siRNAs and transfections

Plasmid transfections were performed using X-tremeGENE 9 DNA transfection reagent (Roche) on 6×105 HEK 293T cells plated in 10 cm dishes 20h prior to transfection. The complexes were incubated with the cells in OptiMEM for 4h before being replaced by fresh media. Cells were harvested 48–72h after transfection. The transfected plasmids were: pCS2-3xHA-KDM4A, pCS2-3xHA-KDM4A-E482A, pMSCV-GFP (10), pMSCV-GFP-KDM4A (10), pMSCV-GFP-KDM4A-E482A, pcDNA3-3xMYC-Cullin1 (8), pSUPER (10), pSUPER-4C (referred as 4A.2 throughout the figures) (10), pLKO, pLKO-A06 (referred as 4A.6 throughout the figures), pLKO-A10 (referred as 4A.10 throughout the figures). For the MTT assays shRNAs were transfected twice 48h apart.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analyses were performed according to (8).

Antibodies

The antibodies used were Actinin (Santa Cruz, sc-17829), Ubiquitin, KDM4A, Cullin 1 and β-Actin antibodies were described in (8).

HapMap frequencies

The HapMap frequencies are from the HapMap Public Release #28 (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-perl/snp_details_phase3?name=rs586339&source=hapmap28_B36&tmpl=snp_details_phase3) (13).

Co-immunoprecipitation

The co-immunoprecipitations experiments were performed as described in (8).

Catalytic activity of KDM4A WT and SNP-A482

All immunofluorescence experiments were performed as in (10). Fifty cells were scored per replicate.

Patient outcome

For complete methods see (15). p values have been calculated based on a recessive model with unadjusted covariates. The time-dependent receiver operator characteristics curve (ROC) analyses have been done as described in (16).

Drug screen

A panel of 86 cell lines were used in a high-throughput viability screen as described before (23). The cell lines were randomly selected out of a collection of 160 lung cancer cell lines available at MGH, and based on the mutational data available they appear to be representative of NSCLC lines in general and capture major mutational events described for this cancer at the expected frequency. All mutational data available are provided in supplementary table 2. Additional details are available at http://www.cancerrxgene.org/ (24). The compounds were targeted agents mostly at late stage of clinical or preclinical development selected based on therapeutic relevance of the drugs themselves or of the targets for compounds not clinically tested. They cover a broad range of targets not restricted to the PI3K pathway including CDK, Aurora, proteasome, EGFR, SRC, IGF1R, MEK. The compounds cover over 50 different nominal targets with some redundancy towards the most clinically relevant targets. The full list of drugs and their primary target is provided as supplementary table 3.

Cells were seeded in 96-well at ~15% confluency in medium with 5% FBS and penicillin/streptavidin. The optimal cell number for each cell line was determined to ensure that each was in growth phase at the end of the assay. After overnight incubation cells were treated with three concentrations of each compound in triplicate 10-fold dilution series) using liquid handling robotics, and then returned to the incubator for assay at a 72h time point. Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 30 minutes and then stained with 1µM of the fluorescent nucleic acid stain Syto60 (Invitrogen) for 1h. Quantitation of fluorescent signal intensity was performed using a fluorescent plate reader at excitation and emission wavelengths of 630/695nM. The mean of triplicate values for each drug concentration was compared with untreated wells, and a viability ratio was calculated.

The statistical association between drug sensitivity and KDM4A SNP-A482 status was tested using a series of Fisher exact tests designed to capture the differential drug effect across the full range of viability observed: for these tests the cell lines were designated as KDM4A SNP-A482 positive if they are homozygous for the minor alleles and compared to heterozygous and homozygous major alleles cell lines grouped together. For each drug and concentration used the cell lines were rank ordered from most to least sensitive and a contingency table was built by designating the top 5% sensitive cell lines as “sensitive” and the rest as “resistant”. The result of the Fisher exact test for this threshold of sensitivity was recorded and the procedure was repeated using as a sensitivity threshold the 10th percentile to the 75th percentile by five percentiles increment. The minimum p value for a given drug across the three concentrations tested is reported. The drug effect is the difference between the mean viability of KDM4A SNP-A482 homozygous cell lines and the mean viability of the other cell lines tested at the concentration matching the reported Fisher’s exact test p value. The statistical significance of the enrichment for mTOR inhibitors in the group of drugs associated with the presence of the minor allele KDM4A SNP-A482 was tested using a Fisher’s exact test with five mTOR inhibitors and 15 other drugs statistically linked to KDM4A SNP-A482 status versus one mTOR inhibitor and 66 other drugs not statistically linked to KDM4A SNP-A482 status.

Monitored cell proliferation assay

Seventy-two hours post transfection, 1×104 HEK 293T cells were seeded per well of a 96 well plate, and then treated after 24h. Cell proliferation was monitored with an xCELLigence system (Roche) (25).

MTT assays

MTT assays were performed following supplier’s instructions from the Cell Proliferation Kit I (MTT) from Roche. For shRNA experiments, after two subsequent shRNA transfections, cells were seeded in 96 wells plates before being treated 24h later. Briefly, 1×104 cells were seeded per well of a 96 well plate and grown for 24h before treatment. Forty-eight hours later, cells were assayed. We determined sensitivity by subtracting the background from to the absorbance.

Statistics

All errors bars represent SEM. Half lives were calculated using a polynomial trend line (8). p values were determined by a two-tailed student’s t test or a two way ANOVA when noted; * represents p<0.05. For the NSCLC patient analyses, frequency comparisons were tested using the chi-square test. Hazard Ratios and the significances of the association were calculated using a Cox model. Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the survival curves. For the drug screen, p values were calculated with Fisher’s exact test.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE.

This report documents the first coding SNP within a lysine demethylase that associates with worse outcome in NSCLC patients. We demonstrate that this coding SNP alters the protein turnover and associates with increased mTOR inhibitor sensitivity, which identifies a candidate biomarker for mTOR inhibitor therapy and a therapeutic target for combination therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Drs. Elnaz Atabakhsh and Yongyue Wei as well as Kelly Biette for their comments and suggestions.

Financial support: The studies conducted in this manuscript were funded by the following agencies: American Cancer Society Basic Scholar Grant, MGH Proton Beam Federal Share Grant (CA059267) and NIH R01GM097360 to J.R.W.; NIH (NCI) grant 5R01CA92824 to D.C.C; NIH (U54 HG006097) to C.H.B.. J.R.W. is the Tepper Family MGH Research Scholar and recipient of the American Lung Association Lung Cancer Discovery Award. A post-doctoral fellowship was provided by the Fund for Medical Discovery (C.V.R). C.V.R is the 2014 Skacel Family Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research Scholar. This research was supported in part by a grant from the Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research. J.C.B. was a Fellow of The Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research and is supported by MGH ECOR Tosteson Postdoctoral Fellowship. This investigation has been aided by a grant from The Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research.

Abbreviation list

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- KDM4A

lysine demethylase 4A

- mTOR

mammalian target of Rapamycin

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3 kinase

- ROC

receiver operator characteristics

- AUC

area under the curve

- WT

wild type

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- HEK 293T

human embryonic kidney 293T

- RCC

renal cell carcinoma

- SEM

standard error of the mean

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest1

1 The authors declare competing financial interests: JRW is a consultant for QSonica.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brookes AJ. The essence of SNPs. Gene. 1999;234:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeron-Medina J, Wang X, Repapi E, Campbell MR, Su D, Castro-Giner F, et al. A polymorphic p53 response element in KIT ligand influences cancer risk and has undergone natural selection. Cell. 2013;155:410–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JC, Espeli M, Anderson CA, Linterman MA, Pocock JM, Williams NJ, et al. Human SNP links differential outcomes in inflammatory and infectious disease to a FOXO3-regulated pathway. Cell. 2013;155:57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barreiro LB, Laval G, Quach H, Patin E, Quintana-Murci L. Natural selection has driven population differentiation in modern humans. Nature genetics. 2008;40:340–345. doi: 10.1038/ng.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Rechem C, Whetstine JR. Examining the impact of gene variants on histone lysine methylation. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong Q, Yu S, Yang Y, Liu G, Shao Z. A polymorphism in JMJD2C alters the cleavage by caspase-3 and the prognosis of human breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5:4779–4787. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black JC, Van Rechem C, Whetstine JR. Histone lysine methylation dynamics: establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Molecular cell. 2012;48:491–507. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Rechem C, Black JC, Abbas T, Allen A, Rinehart CA, Yuan GC, et al. The SKP1-Cul1-F-box and Leucine-rich Repeat Protein 4 (SCF-FbxL4) Ubiquitin Ligase Regulates Lysine Demethylase 4A (KDM4A)/Jumonji Domain-containing 2A (JMJD2A) Protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:30462–30470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.273508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan MK, Lim HJ, Harper JW. SCFFBXO22 Regulates Histone H3 Lysine 9 and 36 Methylation Levels by Targeting Histone Demethylase KDM4A for Ubiquitin-Mediated Proteasomal Degradation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2011;31:3687–3699. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05746-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black JC, Manning AL, Van Rechem C, Kim J, Ladd B, Cho J, et al. KDM4A lysine demethylase induces site-specific copy gain and rereplication of regions amplified in tumors. Cell. 2013;154:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kogure M, Takawa M, Cho HS, Toyokawa G, Hayashi K, Tsunoda T, et al. Deregulation of the histone demethylase JMJD2A is involved in human carcinogenesis through regulation of the G(1)/S transition. Cancer letters. 2013;336:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kauffman EC, Robinson BD, Downes MJ, Powell LG, Lee MM, Scherr DS, et al. Role of androgen receptor and associated lysine-demethylase coregulators, LSD1 and JMJD2A, in localized and advanced human bladder cancer. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2011;50:931–944. doi: 10.1002/mc.20758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Dermitzakis E, Schaffner SF, Yu F, et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature09298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang YT, Heist RS, Chirieac LR, Lin X, Skaug V, Zienolddiny S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of survival in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:2660–2667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heist RS, Zhai R, Liu G, Zhou W, Lin X, Su L, et al. VEGF polymorphisms and survival in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:856–862. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chambless LE, Diao G. Estimation of time-dependent area under the ROC curve for long-term risk prediction. Stat Med. 2006;25:3474–3486. doi: 10.1002/sim.2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bjornsti MA, Houghton PJ. The TOR pathway: a target for cancer therapy. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2004;4:335–348. doi: 10.1038/nrc1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Populo H, Lopes JM, Soares P. The mTOR Signalling Pathway in Human Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences. 2012;13:1886–1918. doi: 10.3390/ijms13021886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Rechem C. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cagle PT, Allen TC, Olsen RJ. Lung cancer biomarkers: present status and future developments. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2013;137:1191–1198. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0319-CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gridelli C, Maione P, Rossi A. The potential role of mTOR inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. The oncologist. 2008;13:139–147. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkins MB, Hidalgo M, Stadler WM, Logan TF, Dutcher JP, Hudes GR, et al. Randomized phase II study of multiple dose levels of CCI-779, a novel mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory renal cell carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:909–918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDermott U, Sharma SV, Settleman J. High-throughput lung cancer cell line screening for genotype-correlated sensitivity to an EGFR kinase inhibitor. Methods in enzymology. 2008;438:331–341. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)38023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garnett MJ, Edelman EJ, Heidorn SJ, Greenman CD, Dastur A, Lau KW, et al. Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature. 2012;483:570–575. doi: 10.1038/nature11005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vistejnova L, Dvorakova J, Hasova M, Muthny T, Velebny V, Soucek K, et al. The comparison of impedance-based method of cell proliferation monitoring with commonly used metabolic-based techniques. Neuro endocrinology letters. 2009;30(Suppl 1):121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.