Abstract

The human placenta is an anatomically unique structure that extrudes a variety of extracellular vesicles into the maternal blood (including syncytial nuclear aggregates, microvesicles, and nanovesicles). Large quantities of extracellular vesicles are produced by the placenta in both healthy and diseased pregnancies. Since their first description more than 120 years ago, placental extracellular vesicles are only now being recognized as important carriers for proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, which may play a crucial role in feto-maternal communication. Here, we summarize the current literature on the cargos of placental extracellular vesicles and the known effects of such vesicles on maternal cells/systems, especially those of the maternal immune and vascular systems.

The human placenta secretes diverse vesicles into the maternal bloodstream. These carry proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids that may play a crucial role in feto-maternal communication.

The placenta is an unusual organ with a short and defined life span. The human placenta is a fetal organ that sits between the fetus and its mother, connecting the fetus to the maternal blood supply. It is highly invasive and the entire surface of the placenta is in contact with the maternal circulation during most of gestation. Therefore, the human placenta effectively behaves as one wall of a maternal “blood vessel.” This phenomenon is quite remarkable because, being a fetal organ, the placenta is in essence a semiallogeneic tissue graft in normal pregnancy and a complete allograft in surrogate or donor egg pregnancies. Therefore, the placenta is nature’s only tissue graft.

The human placenta has a villous (branching) structure. The surface of placental villi is covered by the multinucleated syncytiotrophoblast that is terminally differentiated and is not mitotically active. The growth and replenishment of the syncytiotrophoblast is effected by fusion of underlying mononuclear cytotrophoblasts into this layer. Beneath the cytotrophoblasts is the mesenchymal core of the villus with fetal blood vessels. The syncytiotrophoblast is a remarkable cell, which at least in theory, is a single cell covering the entire surface of the placenta and is the immunological barrier between the maternal immune system and the fetus. In a normal term placenta, the syncytiotrophoblast has an area of some 11–13 m2 (Mayhew 2014). However, the syncytiotrophoblast can be denuded, leaving areas lined by fibrinoid rather than syncytiotrophoblast and presumably before the laying down of this fibrinoid, cells of the villous mesenchymal core or cytotrophoblasts are exposed to the maternal blood, at least temporarily.

In addition to the villous structure of the placenta, the placenta is also in contact with the uterine decidua at numerous points via columns of extravillous trophoblasts that invade from the placenta into the decidua. During the first half of pregnancy, these extravillous trophoblasts invade the uterine stroma and also progress antidromically along the lumens of the spiral arteries. Here, extravillous trophoblasts destroy the smooth muscle of the spiral arteries and replace the endothelial cells that normally line these vessels. Migration of extravillous trophoblasts proceeds as far as the inner third of the myometrium, thereby increasing the surface area of contact between fetal cells and the maternal blood. Thus, when we consider the structure of the placenta there are three areas: (1) the syncytiotrophoblast; (2) areas of syncytiotrophoblast denudation; and (3) the extravillous trophoblasts, that can produce extracellular vesicles that enter the maternal blood and have effects on the mother’s physiology (Fig. 1).

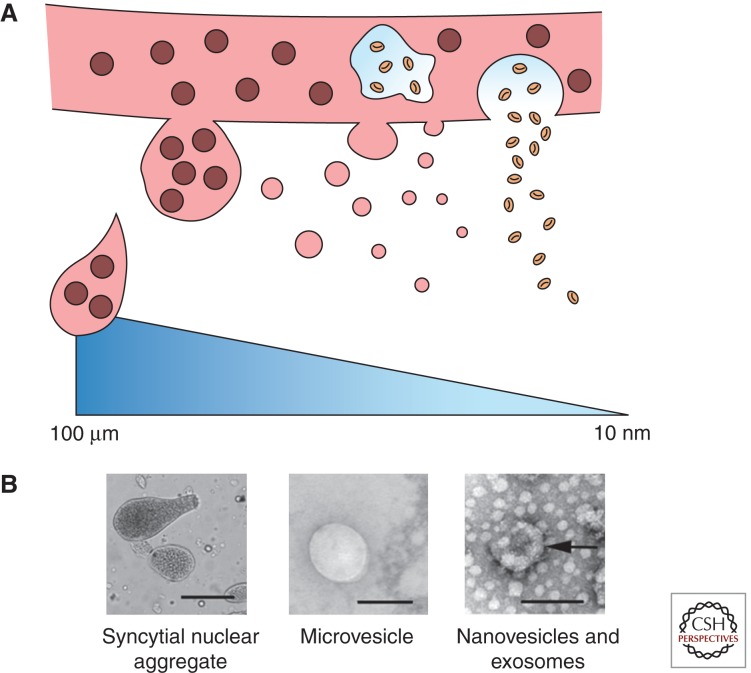

Figure 1.

Different types of extracellular vesicles produced by the placenta. (A) A schematic representation showing the shedding of macrovesicles, microvesicles, and nanovesicles, including exosomes from the syncytiotrophoblast (left to right).(B) Light micrograph of a syncytial nuclear aggregate (scale bar, 50 µm), transmission electron micrograph of a negatively stained microvesicle (scale bar, 100 nm), and transmission electron micrograph of a negatively stained exosome (arrow) with other nanovesicles (scale bar, 100 nm).

THE PLACENTA PRODUCES A WIDE RANGE OF EXTRACELLULAR VESICLES

In the current literature, there is considerable confusion regarding what various vesicles should be called and how they should be isolated, regardless of the cell type producing them. We have included a summary of the published preparation methods used in the placental research area (Table 1) and we refer readers to recent general reviews on this topic (Raposo and Stoorvogel 2013; Kowal et al. 2014). Although many cells produce extracellular vesicles, the cellular structure of the placenta is such that the placenta produces a wider variety of vesicles than other cell types.

Table 1.

Summary of purification methods used for studies of placental micro/nanovesicles

| Reference(s) | Starting material | Original spins | Final spin | Markers for exosomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khalfoun et al. 1986 | Mechanically dissected term villous tissue | 1000g × 10 min, 10,000g × 10 min | 10,000g × 60 min | – |

| Smarason et al. 1993 | Mechanically dissected term villous tissue | 2000g × 10 min, 10,000g × 10 min | 50,000g × 45 min | – |

| Cockell et al. 1997 | Term placentae, stirred overnight | 800g × 10 min, 10,000g × 5 min | 100,000g × 60 min | – |

| Knight et al. 1998 | Plasma diluted 1:1 with PBS | – | 150,000g × 45 min | – |

| Abrahams et al. 2004 | Trophoblast cell supernatants | 500g × 20 min twice | 125,000g × 3 h | – |

| Aly et al. 2004 | Mechanically dissected term villous tissue | 2000g × 10 min, 10,000g × 10 min | 50,000g × 45 min | – |

| Gupta et al. 2005b | Term placentae (mechanical, explant culture, perfusion) | 1000g × 10 min, 10,000g × 10 min | 70,000g × 90 min | – |

| Goswami et al. 2006 | Plasma | – | 150,000g × 45 min | – |

| Sabapatha et al. 2006 | Plasma | Size exclusion chromatography | 100,000g × 60 min | |

| Taylor et al. 2006 | Serum | Size exclusion chromatography | 100,000g × 60 min & discontinuous sucrose gradient | TSG101+ PLAP+ |

| Germain et al. 2007 | Plasma | 2000g × 15 min | 150,000g × 45 min | – |

| Lok et al. 2008a | Plasma | 1560g × 20 min | 18,890g × 30 min | – |

| Orozco et al. 2008 | Jeg3 cell supernatants | 300g × 5 min, 800g × 5 min | 25,000g × 60 min | – |

| Pap et al. 2008 | Whole blood | 1500g × 5 min, 130,000g × 10 min | 100,000g × 20 min | – |

| Reddy et al. 2008 | 10 mL blood | 2000g × 10 min, 10,000g × 10 min | 150,000g × 45 min | – |

| Aharon et al. 2009 | Platelet-poor plasma (PPP) by centrifugation of whole blood at 1500g × 10 min twice | – | 18,000g × 30 min | |

| Hedlund et al. 2009 | Supernatants from cultured first trimester placentae | 4000g × 30 min, 17,000g × 25 min, 0.2 µm filter, 110,000g × 60 min, PBS wash | 20% and 40% sucrose gradients | CD63+, GRP78– |

| Luo et al. 2009 | BeWo cell supernatants | 2300g × 5 min, 0.8 µm filter disk, ultracentrifugal filtering with 100 kDa cutoff | CD63+ beads isolation | CD63+ beads isolation |

| Messerli et al. 2010 | Culture supernatants from term placentae (or mechanically dissected and perfused samples) | 1000g × 10 min, 10,000g × 10 min | 60,000g × 90 min | – |

| Atay et al. 2011a | Sw.71 1st trimester trophoblast cell line supernatant | 400g × 10 min, 15,000g × 20 min, ultrafiltration at 500 kDa cut off | 100,000g × 60 min | – |

| Gardiner et al. 2011 | Term placental perfusate | 600g × 10 min | 150,000 g | – |

| Guller et al. 2011 | Term placental perfusate | 1500g × 10 min twice | 10,000g × 30 min for 10 k STBM; 150,000g × 2 h for 150 k STBM | – |

| Southcombe et al. 2011 | Mechanically dissected term placentae | 600g × 10 min | 150,000g × 60 min | – |

| Perfused or cultured term placentae | 600g × 10 min, 10,000g × 10 min | 48,000g × 45 min | – | |

| Abumaree et al. 2012 | Term placental explants | – | 550g × 10 min | – |

| Donker et al. 2012 | Term cytotrophoblast (CTB) supernatant | 300g × 5 min, 1200g × 10 min, 10,000g × 30 min | 100,000g × 60 min | TSG101+ |

| Holder et al. 2012a | Supernatants from cultured first trimester placental explants and BeWo cells | 1000g × 10 min, 10,000g × 10 min | 70,000g × 90 min | – |

| Kshirsagar et al. 2012 | Supernatants from cultured placental explants | 300g × 10 min, 2000g × 20 min, 10,000g × 30 min | 100,000g × 1.5 h | Verified density by sucrose gradients CD63+ LAMP1+ |

| Lee et al. 2012 | CRL1584 trophoblast cell line supernatant | 300g × 5 min, 800g × 5 min | 100,000g × 90 min | – |

| Rajakumar et al. 2012 | Culutured term placental explants | 800g × 5 min | 415,000g × 90 min | – |

| Tolosa et al. 2012 | Supernatants from cultured term placental explants | 300g × 15 min, 2000g × 15 min, 15,000g × 60 min, 0.22 µm filter | 100,000g × 70 min, 30% sucrose cushion 110,000g × 94 min, 20%–60% discontinuous sucrose gradient | TSG101+ GRP78+ |

| BeWo cell supernatant | 2000g × 10 min, 10,000g × 60 min, 0.22 µm filter | 100,000g × 70 min on 30% sucrose cushion, then PBS wash and 100,000g × 2 h | ||

| Term CTB supernatant | 2000g × 30 min, 10,000g × 30 min | 100,000g× 30 min | ||

| Baig et al. 2013 | Term placental explants | 1000g × 10 min, 10,000g × 10 min | 100,000g × 60 min | – |

| Delorme-Axford et al. 2013 | Term CTB or JEG-3 supernatant | 300g × 5 m, 1200g × 10 min, 10,000g × 30 min, 25,000g × 25 min | 108,000g × 60 min | – |

| Salomon et al. 2013 | Placental mesenchymal stem cell supernatant | 300g × 15 min, 2000g × 30 min, 12,000g × 45 min, 0.22 µm filter | 100,000g × 75 min, PBS wash, then 30% sucrose cushion for 110,000g × 75 min | CD63+ CD81+ CD9+ |

| Stenqvist et al. 2013 | Culture supernatant from placental explants | 4000g × 30 min, 17,000g × 25 min, 0.2 µm filter | 110,000g × 2 h, then 20%–40% discontinuous sucrose gradient | CD63+ |

| Tannetta et al. 2013 | Mechanically dissected term placentae | 600g × 10 min | 150,000g × 45 min | – |

| Perfused term placentae | 600g × 10 min | 150,000g × 60 min | – | |

| Cronqvist et al. 2014 | Term placental perfusate | 1500g × 10 min twice | 10,000g × 30 min for 10 k STBM; 150,000g × 2 h for 150 k STBM | – |

| Vargas et al. 2014 | Term CTB | 300g × 10 min, 10,000g × 30 min | ExoQuick or 100,000g × 60 min | AChE activity CD63+ TSG101+ Grp78- |

Macrovesicles (Syncytial Nuclear Aggregates)

In 1893, the German pathologist Georg Schmorl first reported the presence of large multinucleated structures trapped in the lungs of women who had died in pregnancy. He identified the origin of these structures as the placental syncytiotrophoblast (Schmorl 1893; Lapaire et al. 2007). Today, we refer to these multinucleated structures as syncytial nuclear aggregates (SNAs). SNAs range in size from 20 µm to several hundred microns and can contain many tens/hundreds of nuclei (Chua et al. 1991). We recently estimated that on average, SNAs from first trimester placentae contain ∼60 nuclei and that the average volume was 48,000 µm3. In addition to fetal DNA, SNAs also carry large amounts of fetal protein, RNA and other factors that can influence the behavior of maternal cells.

How or why SNAs are shed from the placenta is not yet clear. One possible source is the unintentional detachment of newly budding villi from the placental surface. Alternatively, it has been suggested that SNAs may be the end of the life cycle of the syncytiotrophoblast. It is suggested that aged nuclei cluster together in the syncytiotrophoblast and are then extruded into the maternal blood. If the latter hypothesis is the case, then SNAs may represent the equivalent of apoptotic blebs that bud from the surface of cells dying by programmed cell death, in which the dangerous contents of the dying cells are safely packaged for destruction by phagocytes. It is likely that SNAs in the maternal blood come from a mixture of these sources. We have shown that SNAs produced in vitro from both early gestation and term placentae show markers of programmed cell death and this may be important to induce an anti-inflammatory or tolerogenic response from the mother to this fetal material.

It is not clear exactly how the production of macrovesicles by the placenta changes with gestation. SNAs have been shown in the maternal peripheral blood from as early as 6 wk of gestation but the levels of these structures in the maternal blood did not correlate with gestational age (Covone et al. 1984). We have shown that the production of macrovesicles from placental explants is greatest (per mg of tissue) in the first trimester with a decline in production during the second and third trimesters (Abumaree et al. 2012). Whether these changes reflect changes in the production of macrovesicles by the placenta, or that the more tightly packed villous structure of the second and third trimester placenta prevents the vesicles escaping into the intervillous spaces in static explant culture in vitro is not clear.

Microvesicles

In general, microvesicles are derived from budding of the plasma membrane of cells (Raposo and Stoorvogel 2013), however, the exact origin of placental microvesicles is unclear. The syncytiotrophoblast has a microvillous surface, which is important for slowing down the movement of maternal blood over the surface of the syncytiotrophoblast to facilitate increased transfer of nutrients and gases across the placenta. It has long been thought that parts of the microvilli may be shed into the maternal blood as microvesicles and early preparations of microvesicles from the syncytiotrophoblast involved mechanical disruption of the microvillous membrane (Khalfoun et al. 1986; Thibault et al. 1991; Smarason et al. 1993). Physiologically, what would cause the shedding of microvilli is unclear, as we have found that large amounts of microvesicles are shed from villous placental explants in static culture.

We have recently reported that approximately one third of SNAs have obvious blebs on their surfaces (Fig. 2), and this is a possible source of trophoblast microvesicles (Chamley et al. 2014). The production of apoptotic blebs by the syncytiotrophoblast is another potential source of trophoblast microvesicles. It is also possible that villous cytotrophoblasts exposed to the maternal blood following denudation of the syncytiotrophoblast or extravillous trophoblasts could also be minor sources of trophoblast microvesicles. Platelets and other cell types release microvesicles in response to activating stimuli, and it is possible that trophoblasts have a similar response to a variety of yet undetermined stimuli.

Figure 2.

Optical section through a syncytial nuclear aggregate generated by confocal microscopy. The cytoplasm is stained green with Cell Tracker and nuclei are stained blue with Hoerchst. A large number of surface blebs can be seen on the surface of the syncytial nuclear aggregate (arrowed).

The amount of trophoblast microvesicles in the maternal plasma has been reported to increase with increasing gestation in normal pregnancy but this increase with gestation was not as marked in women with preeclampsia (Knight et al. 1998).

Nanovesicles

Nanovesicles are shed in large quantities from the syncytiotrophoblast in normal pregnancies and encompass a mixture of exosomes and other vesicles of ∼20–100 nm in diameter. The origin of nonexosomal nanovesicles is unclear, but they are thought to be derived from the plasma membrane of trophoblasts, in contrast to exosomes that are produced inside the cell as multivesicular bodies derived from endosomes (for review of exosome production, see Kowal et al. 2014). There are a number of suggested markers of exosomes such as CD63 and CD81 (Table 1), but whether these markers are specific for exosomes, especially those of placental origin, remains an open question.

It has recently been shown that the amount of exosomes shed into the maternal blood increased with increasing gestational age, most likely reflecting increasing placental size as gestation progresses (Salomon et al. 2013).

Trophoblast Deportation

Once this range of trophoblast extracellular vesicles is shed from the placenta, they are drained into the maternal circulation through the uterine vein. This process is known as trophoblast deportation. Interestingly, it has been reported that trophoblastic membrane antigens are not detected in retroplacental cord blood, which suggest that trophoblast deportation is restricted to the maternal aspect of the human placenta (O’Sullivan et al. 1982). However, multiple studies have shown the presence of vesicles in amniotic fluid (Asea et al. 2008; Keller et al. 2011). Although these vesicles are likely to be important to pregnancy, they are unlikely to enter the maternal circulation and interact with maternal organs. In addition to the trophoblast-derived extracellular vesicles, placental mesenchymal stem cells have also been shown to secrete exosomes in vitro that potentially could enter the maternal blood with consequences for maternal cells (Salomon et al. 2013). However, the fate of such vesicles in vivo is unknown, and as the main focus of this review is on the effects of trophoblast-derived extracellular vesicles on maternal cells, we will not discuss the above vesicle types further.

THE PRODUCTION OF PLACENTAL VESICLES IS INCREASED IN PREECLAMPSIA

Preeclampsia is a potentially fatal hypertensive disorder specific to human pregnancy in which maternal blood pressure becomes dangerously elevated in response to an as yet unidentified “toxin or toxins” released from the placenta. There is growing evidence that placental vesicles may be involved in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia by carrying at least a component of the toxin(s) released from the placenta. It is well documented that there is an increase in shedding of placental macrovesicles (SNAs) during preeclampsia (Attwood and Park 1961; Chua et al. 1991; Buurma et al. 2013). Similarly, the shedding of placental microvesicles into the maternal blood is also increased in women with early onset preeclampsia (Goswami et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2012b), with levels in the maternal blood correlating with systolic blood pressure (Lok et al. 2008b). However, the level of circulating placental microvesicles does not seem to be altered in women with late onset preeclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction (Goswami et al. 2006). It is likely that both quantitative, as well as qualitative, changes in the shedding of these placental vesicles are important in disease states.

WHAT ARE THE CARGOS OF PLACENTAL EXTRACELLULAR VESICLES?

For many years, it was thought that the largest of the placental extracellular vesicles, SNAs, were nothing more than a waste disposal system, allowing the removal of obsolete cellular material from the syncytiotrophoblast and that the smaller vesicles may also be similar waste disposal systems (Park 1975). However, it is becoming apparent that placental extracellular vesicles are part of the complex communication and interplay between the fetus and its mother. The nature of this communication is likely to be dependent on the cargos of fetal material carried by these vesicles.

Proteins

Placental extracellular vesicles carry a large number of proteins that have the potential to be active in the mother. A database of the proteomes of extracellular vesicles has recently been established and this database contains information about the protein, RNA, and lipid content of placental extracellular vesicles from multiple studies. (We refer interested readers to the “Vesiclepedia” located at http://microvesicles.org/#)

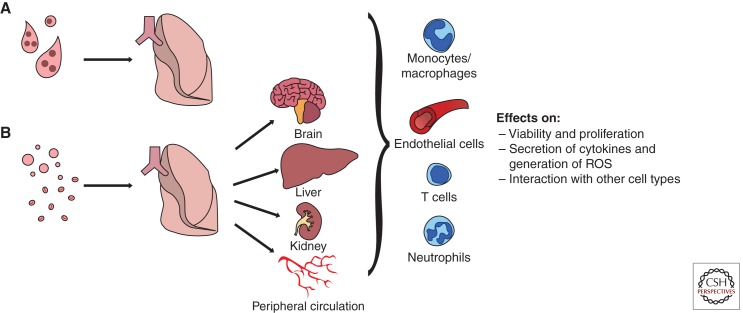

Several classes of proteins are of particular interest to placental biologists when investigating placental vesicles. These include immunologically relevant proteins, vasoactive proteins, as well as proteins involved in thrombosis. Another area of particular interest that remains relatively unexplored is whether any signals exist on placental vesicles to target them to particular organs or cell types (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Hypothesized targets of placental extracellular vesicles once they are shed from the placenta and deported in the maternal blood. (A) Syncytial nuclear aggregates are trapped in the maternal lungs and are most likely cleared by endothelial cells. (B) In contrast, micro- and nanovesicles can freely pass through the lungs and enter the peripheral circulation where they could potentially have effects on multiple organ systems in both normal and diseased pregnancies, like preeclampsia.

Immune regulatory proteins

Because the fetus and its placenta express both maternally and paternally derived genes, those that are derived from the father have the potential to be seen as foreign antigens by the maternal immune system. The placenta uses multiple pathways to avoid maternal immune attack, including the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines and expression of cell-surface immune regulatory molecules. Like the trophoblast from which they are derived, placental extracellular vesicles have been shown to carry, among others, the immunomodulatory proteins; Fas ligand, TRAIL, CD274, CD276, and HLA-G5, which may contribute to apoptosis and/or reduced activity of maternal T cells during pregnancy (Abrahams et al. 2004; Frangsmyr et al. 2005; Sabapatha et al. 2006; Pap et al. 2008; Kshirsagar et al. 2012; Stenqvist et al. 2013). Syncytin-1 is also carried by placental extracellular vesicles (Than et al. 2008; Holder et al. 2012a), and recombinant syncytin 1 has been shown to be able to reduce the secretion of proinflammatory TNFα and IFNγ from leukocytes, such that interaction between syncytin 1 bearing placental vesicles and leucocytes might result in the reduced production of these proinflammatory cytokines in healthy pregnancies (Than et al. 2008).

A major strategy used by the placenta to avoid maternal immune recognition is the lack of expression of HLA proteins on the syncytiotrophoblast. The HLA proteins are used by the immune system to distinguish self from nonself antigens and are also known as the transplantation antigens because mismatching of the HLA system leads to transplant rejection. Although the HLA system is the major immune recognition system, it has long been known that even transplants closely matched for the HLA system may be rejected if a second set of immune recognition molecules, called the minor histocompatibility antigens, are mismatched. It has recently been shown that the syncytiotrophoblast and SNAs express several of the minor histocompatibility antigens (Holland et al. 2012). It has been proposed that in normal pregnancy, minor histocompatibility antigens carried by placental extracellular vesicles may be processed by maternal antigen presenting cells to help induce maternal immune tolerance to paternally derived minor histocompatibility antigens.

Proteins that can influence the vascular system

It is not clear which maternal cells are responsible for clearing placental extracellular vesicles from the maternal blood, and although it is commonly assumed that the professional phagocytes of the maternal immune system are responsible for clearance of such vesicles, it is also likely that maternal endothelial cells are involved in this process. Therefore, proteins contained in placental extracellular vesicles may influence the maternal vasculature and this may be particularly important in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Flt-1 is a receptor for the angiogenic/vasoactive factors, VEGF and PlGF, and the truncated, soluble form of Flt-1 is implicated in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia (Maynard et al. 2003; Levine et al. 2004). Flt-1 has been reported to be present on both SNAs (Rajakumar et al. 2012; Buurma et al. 2013) and placental microvesicles (Lok et al. 2008a; Tannetta et al. 2013). This vesicle-borne Flt-1 may have the same effect as soluble Flt-1, sequestering VEGF and PlGF. The relevance of this to preeclampsia is revealed in the finding that microvesicles derived from preeclamptic placentae carried more Flt-1 than those from healthy term placentae (Tannetta et al. 2013). Similarly, the soluble form of endoglin (part of a TGFβ receptor) is also implicated in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia via its effects on the vasculature. It has been shown that a significant portion of the apparently soluble endoglin detected in placental perfusates was associated with microvesicles rather than being truly soluble (Guller et al. 2011). Placental microvesicles also carry the procoagulant protein, tissue factor, and thus placental vesicles may contribute to the prothrombotic state of pregnancy (Aharon et al. 2009).

Proteins that might allow placental extracellular vesicles to interact selectively with different cellular targets

Interestingly, it has been recently proposed that the expression of tetraspanins, which are proteins that are specifically enriched in exosomes, may play an important role in target cell selection. For example, tetraspanin 8α4 may be important to target exosomes to endothelial cells and the pancreas (Rana and Zoller 2011; Rana et al. 2012). In addition, fibronectin is also expressed on placental exosomes, which may be an important ligand to allow interaction with integrin α5β1, allowing the exosomes to tether to macrophages (Atay et al. 2011a). Syncytin 1 and syncytin 2 have also been reported to be present on exosomal membranes, and it is postulated that the presence of the syncytins on vesicles may be important for uptake of vesicles by cytotrophoblasts (Vargas et al. 2014).

Nucleic Acids

Trophoblastic macrovesicles (SNAs) are multinucleated, containing hundreds of copies of the fetal genome. The presence of fetal DNA in placental extracellular vesicles is also supported by the colocalization of DNA and HLA-G in vesicles found in the plasma of pregnant women (Orozco et al. 2009). Similarly, microvesicles derived from trophoblast or explant cultures in vitro contained DNA (Gupta et al. 2004; Orozco et al. 2008). In preeclampsia, an increase in circulating DNA-positive microvesicles was reported (Orozco et al. 2008) and much of the cell-free fetal DNA that is analyzed for antenatal trisomy 21 screening is thought to be contained in vesicles (Colucci et al. 1993; Bischoff et al. 2005).

In addition to DNA, there is growing evidence that placental vesicles also contain potentially functional RNA. For example, the clearance pattern of circulating placental microvesicles is very similar to that of “cell-free” placental CRH mRNA suggesting this cell-free RNA was contained in the microvesicles (Reddy et al. 2008). Likewise, it has been suggested that, at least some, SNAs are transcriptionally active and contain mRNA from which transcription can occur (Rajakumar et al. 2012). The condition of the placenta from which vesicles are derived, as well as the method of preparation of the vesicles may impact on the quality or quantity of RNA contained in the vesicles. It has been shown that the levels and proportion of mRNA present, compared with DNA, depended on the method used to generate the microvesicles (Gupta et al. 2004). The level of mRNA present in placental vesicles may also be inversely related to the amount of oxidative stress experienced by the original tissue (Rusterholz et al. 2007).

Recently, the exciting observation that primary trophoblasts can secrete exosomes containing functional placenta-specific miRNA was reported (Delorme-Axford et al. 2013). The C19MC cluster of miRNA is expressed almost exclusively in the placenta (Luo et al. 2009), and it was reported that placental exosomes predominately carry this family of miRNA (Donker et al. 2012). In an in vitro model of preeclampsia, term placentae that have been perfused with hemoglobin produce microvesicles that showed a down-regulation of miRNA-517a/b (part of the C19MC cluster) (Cronqvist et al. 2014), suggesting that changes in the content of nucleic acids in placental vesicles could contribute to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

Lipids

It has been shown that exosomes, in general, are enriched for cholesterol and sphingomyelins, which may modulate recipient cell homeostasis (Baig et al. 2013; Record et al. 2014). The levels of various lipids are altered in the placenta in preeclampsia, as well as recurrent miscarriage, and as exposed negatively charged lipids may stimulate thrombosis, the increased load of placental extracellular vesicles observed in preeclampsia may contribute to the pathogenesis of this condition (Alijotas-Reig et al. 2009; Baig et al. 2013). Interestingly, placental microvesicles produced by mechanical disruption of the placenta are reported to carry more lipids than microvesicles produced via perfusion or explant culture methods (Gupta et al. 2008). In one study, artificial microvesicles containing 80% phosphatidylcholine and 20% phosphatidylserine were injected into pregnant mice and these vesicles induced increased blood pressure, intrauterine growth restriction, and placental hypercoagulation (Omatsu et al. 2005). Given the crucial role of phospholipids in coagulation/haemostasis and other cellular signaling processes, the nature and quantity of lipids carried by placental extracellular vesicles may play an important role in mediating their effects on maternal physiology.

INTERACTIONS OF PLACENTAL EXTRACELLULAR VESICLES WITH MATERNAL CELLS

Immune Cells

The interactions between maternal immune cells and placental extracellular vesicles has been widely studied, but there is little consensus regarding the effects of the vesicles on immune cells, or even with which immune cells these vesicles can interact. This is in part a reflection of the different methods used to prepare vesicles in vitro and also differences in the immune cells examined. For example, it has been reported that HLA-G positive microvesicles isolated from the blood of pregnant women can bind to T cells, but not B cells nor NK cells (Pap et al. 2008). However, another study showed that placental microvesicles can interact with B cells and monocytes (Southcombe et al. 2011).

It has clearly been shown that the effects placental microvesicles have on immune cells depended on how they were produced (Gupta et al. 2005b). This study showed that microvesicles isolated by mechanical disruption of placentae or by culturing placental explants had anti-inflammatory effects on T cells, whereas microvesicles isolated by placental perfusion were more proinflammatory (Gupta et al. 2005b). These investigators also showed that placental microvesicles did not activate resting T cells nor affect their viability (Gupta et al. 2005b). However, if T cells were first activated with phorbol mysterate acetate (PMA), the placental vesicles affected T cell proliferation, activation and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, depending on the method of vesicle production (Gupta et al. 2005b).

Studies reporting that placental extracellular vesicles have predominantly proinflammatory effects on leucocytes

Several studies have shown that microvesicles from first trimester and preeclamptic placentae can induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines from both naïve and primed peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Southcombe et al. 2011; Holder et al. 2012b; Stenqvist et al. 2013). Placental microvesicles also increased IL-1α secretion by both naïve and primed PBMCs (Thibault et al. 1991), and increased the production of TNFα, IL-12, IL-18, and IFNγ from primed PBMCs (Germain et al. 2007). In addition, microvesicles from preeclamptic placentae were reported to exacerbate the reaction of PBMCs to lipopolysaccharide whereas placental microvesicles from normal placentae had the opposite effect, dampening the response of PBMCs to an LPS challenge (Holder et al. 2012b). Others have shown that the activating effects of placental microvesicles on PBMCs were more pronounced when the vesicles were derived from hypoxic trophoblasts, compared with vesicles derived from normoxic trophoblasts (Lee et al. 2012).

Studies reporting that placental extracellular vesicles have predominately anti-inflammatory effects on leucocytes

On the other hand, there is a substantial body of literature that suggests that placental microvesicles are anti-inflammatory. Several reports showed that placental microvesicles inhibited PBMC proliferation and prevented the activation of lymphocytes by activators such as phorbol ester and calcium ionophore (Degenne et al. 1991; Thibault et al. 1991, 1992). Similarly, microvesicles from term placentae were shown to sequester transferrin and reduce lymphocyte responsiveness to phytohemagglutinin without affecting lymphocyte viability (Khalfoun et al. 1986). Placental micro/nanovesicles can also mediate localized T-cell apoptosis via expression of Fas ligand by the vesicles (Abrahams et al. 2004; Frangsmyr et al. 2005; Stenqvist et al. 2013). Fas ligand present on placental exosomes isolated from healthy term placentae or maternal blood was also partially responsible for suppressing CD3ζ and JAK3 expression, and inducing SOCS-2 expression in T cells, which prevents their activation (Sabapatha et al. 2006; Taylor et al. 2006).

Placental micro/nanovesicles have also been shown to carry the immune modifying MHC class I chain related protein A and B, as well as ULBP1-5, which can engage and down-regulate NKG2D on PBMCs, including NK cells and γδ T cells (part of the innate immune system) (Mincheva-Nilsson et al. 2006; Hedlund et al. 2009). Because NKG2D is an activating receptor, these studies suggest that the down-regulation of NKG2D would likely prevent the activation of NK cells at the materno-fetal interface and induce immunotolerance (Hedlund et al. 2009).

The differential effects of placental extracellular vesicles on maternal immune cells suggest that the condition of the pregnancy (normal or diseased) may have a major effect on the response of maternal immune cells to these vesicles.

Studies reporting the interactions of placental extracellular vesicles with monocytes/macrophages

Whether placental extracellular vesicles induce activation of monocytes/macrophages or keep them in a quiescent state is still unclear. There is currently support for both hypotheses.

First, placental macrovesicles (SNAs) can be phagocytosed by macrophages where they stimulate the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines and decrease their production of proinflammatory cytokines (Abumaree et al. 2006, 2012). In addition, after phagocytosis of macrovesicles from normal placentae, macrophages up-regulate the immunosuppressive tryptophan metabolizing enzyme, indoleamine dioxygenase, and increased expression of the negative T cell regulatory protein, programmed death ligand 1 (Abumaree et al. 2006, 2012).

On the other hand, although placental microvesicles also bind to monocytes (Southcombe et al. 2011), they are reported to induce a proinflammatory phenotype in these cells, increasing their expression of CD54, IL-8, IL-6, and IL1β (Messerli et al. 2010). Similarly, placental exosomes are also internalized by monocytes and can induce monocyte migration and production of proinflammatory cytokines like IL1β, IL-6, G-CSF, and TNFα (Atay et al. 2011a). Interestingly, the secretion of some inflammatory cytokines by monocytes, such as CCL-11, require phagocytosis of the exosomes, whereas the secretion of other inflammatory cytokines, like IL1β, only require exosomes to be tethered to the monocytes through fibronectin–integrin interactions (Atay et al. 2011b).

Studies reporting the interactions of placental extracellular vesicles with neutrophils

Microvesicles prepared by mechanical disruption of preeclamptic placentae were shown to dramatically increase the production of superoxides by donor neutrophils (Aly et al. 2004). Vesicles isolated by culturing preeclamptic placental explants also activated neutrophils in vitro and stimulated the generation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETS), which consist of networks of DNA that entrap extracellular microorganisms and/or other structures such as vesicles (Gupta et al. 2005a). In preeclamptic placentae, NETs are much more abundant than in normal placentae, reportedly filling up large areas of the intervillous space, potentially reducing maternal blood flow around the placenta (Gupta et al. 2005a).

Endothelial Cells

We have previously shown that trophoblastic macrovesicles shed from normal placentae have features of apoptosis and that phagocytosis of these vesicles by endothelial cells protects them against the activation/dysfunction induced by potent cell activators such as PMA and proinflammatory cytokines like IL-6 (Chen et al. 2012a). In contrast, if these macrovesicles were induced to undergo secondary necrosis by freeze–thawing, phagocytosis of the vesicles induced endothelial cell activation (Chen et al. 2006), resulting in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, which could then activate additional endothelial cells, thereby spreading endothelial cell dysfunction from the initial point of contact with the placental vesicles (Chen et al. 2009, 2010).

In more physiological studies, we showed that macrovesicles from preeclamptic placentae can also cause endothelial cell activation whereas vesicles from control normotensive placentae do not (Shen et al. 2014). These effects were dependent on the macrovesicles being phagocytosed by the endothelial cells and were associated with changes in nitric oxide and calcium signaling in the endothelial cells (Chen et al. 2013).

Similar observations were reported by others studying the effects of placental microvesicles on endothelial cells. von Dadelszen et al. (1999) reported that the conditioned media derived from culturing endothelial cells with microvesicles from normal term placentae was proinflammatory and could activate resting monocytes, granulocytes, and lymphocytes (von Dadelszen et al. 1999). It has also been shown that microvesicles derived from normal term placentae can inhibit proliferation and increase apoptosis of endothelial cells (Smarason et al. 1993; Chen et al. 2012b). Electron microscopic examination revealed extensive disruption of the usual honeycomb structure of the endothelium by placental microvesicles (Smarason et al. 1993; Cockell et al. 1997). In contrast, it has recently been shown that plasma-derived exosomes from pregnant women promoted the migration of endothelial cells compared with exosomes from nonpregnant women (Salomon et al. 2013). These differences highlight the potential for different types of vesicles to have varied effects on maternal cells.

Exactly how placental vesicles effect these changes in endothelial cells is not clear, but it has been reported that placental microvesicles may induce changes in the transcriptome of endothelial cells, affecting genes involved in endothelial proliferation, possibly through the unfolded protein response pathway (Hoegh et al. 2006). Furthermore, placental microvesicles can also bind physiologically relevant concentrations of VEGF and PlGF, resulting in the disruption of endothelial monolayers (Tannetta et al. 2013). Placental microvesicles were also reported to inhibit acetylcholine-induced vasodilation of arteries preconstricted with noradrenaline (Cockell et al. 1997).

Similar to the variations observed in immune cell responses, the effects of placental microvesicles on endothelial cells were also dependent on the method of preparation. For example, mechanically prepared microvesicles decreased endothelial proliferation and increased apoptosis, resulting in detachment of endothelial cells, whereas microvesicles derived from explant cultures or placental perfusion decreased endothelial cell proliferation but did not cause endothelial apoptosis or affect monolayer morphology (Gupta et al. 2005c). Further studies comparing methods for producing placental vesicles in vitro suggested that mechanically prepared microvesicles show higher lipid content than vesicles prepared by explant culture or placental perfusion methods and this is, in part, responsible for the inhibition of proliferation and increase in apoptosis of endothelial cells observed (Gupta et al. 2008).

Remodeling of the spiral arteries by invasive trophoblasts, the so-called “physiological changes of pregnancy,” is a key requirement for successful pregnancy (Brosens et al. 1967). This remodeling involves extravillous trophoblasts replacing the endothelial cells that normally line the spiral arteries and loss of the surrounding vascular smooth muscle cells from the remodeled vessels. Recently, Salomon et al. have shown that exosomes from two extravillous trophoblast-like cell lines (JEG-3 and HTR-8-SVneo) promote the migration of vascular smooth muscle cells and they suggest that this may contribute to the loss of smooth muscle cells during spiral artery remodeling (Salomon et al. 2013).

Several studies have now also been performed using microvesicles derived from preeclamptic placentae. First, microvesicles from preeclamptic placentae reduced endothelial cell proliferation more than those from normal pregnancies (Knight et al. 1998), and this may be through increased Flt-1 levels present in these pathological vesicles (Tannetta et al. 2013). Microvesicles isolated from preeclamptic placentae also reduced the lag time, as well as time to peak, of thrombin generation in platelet poor plasma (Gardiner et al. 2011).

Recently, it has been shown that trophoblasts isolated from term placentae were more resistant to infection by a range of viral types (coxsackie B3, polio, vesicular stomatitis, vaccinia, herpes simplex, and cytomegalovirus) than other nontrophoblast cell types (Delorme-Axford et al. 2013). These investigators showed that resistance to these viruses could be transmitted to endothelial cells and fibroblasts by exosomes produced by trophoblasts. This resistance was conveyed by miRNAs of the C19MC cluster that were carried by the vesicles and transferred into the recipient cells (Delorme-Axford et al. 2013). The C19MC miRNAs appeared to function by inducing autophagy in cells which restricted the viral infection.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

It is becoming clear that placental extracellular vesicles are highly likely to be involved in communication from the fetus to its mother. There is confusion in the entire field of extracellular vesicles as to the definitions of vesicles, markers for the various classes of vesicles, and methods for their isolation. This confusion extends into the field of placental extracellular vesicles such that at present it is difficult to directly compare the results of many studies. This is a relatively new field that is growing rapidly and it is already clear that placental extracellular vesicles can influence the function of a multitude of maternal cell types, especially those of the immune and vascular systems. The mechanism by which placental vesicles cause changes in the phenotype and behavior of maternal target cells has not been investigated in any depth as yet, but as interest grows in this field we anticipate that in the near future investigators will begin to focus more on examining these mechanisms to determine whether, for example, the vesicles induce changes in transcription in the target cells by delivering functional RNAs or whether other mechanisms are more important. To date, the majority of reports have focused on the protein cargos of the placental extracellular vesicles, but we believe that work in the future will show that in addition to proteins, other contents of placental vesicles such as regulatory RNAs (because of their remarkable extracellular stability) will be important players in the essential communication between the fetus and its mother in both healthy and diseased pregnancies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Olivia Holland for providing the image in Figure 1 and Mr. Edison Zhang for his assistance in preparing Figures 2 and 3. M.T. is a recipient of the University of Auckland Health Research Doctoral Scholarship.

Footnotes

Editors: Diana W. Bianchi and Errol R. Norwitz

Additional Perspectives on Molecular Approaches to Reproductive and Newborn Medicine available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Abrahams VM, Straszewski-Chavez SL, Guller S, Mor G 2004. First trimester trophoblast cells secrete Fas ligand which induces immune cell apoptosis. Mol Hum Reprod 10: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abumaree MH, Stone PR, Chamley LW 2006. The effects of apoptotic, deported human placental trophoblast on macrophages: Possible consequences for pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol 72: 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abumaree MH, Chamley LW, Badri M, El-Muzaini MF 2012. Trophoblast debris modulates the expression of immune proteins in macrophages: A key to maternal tolerance of the fetal allograft? J Reprod Immunol 94: 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharon A, Katzenell S, Tamari T, Brenner B 2009. Microparticles bearing tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor in gestational vascular complications. J Thromb Haemost 7: 1047–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alijotas-Reig J, Palacio-Garcia C, Vilardell-Tarres M 2009. Circulating microparticles, lupus anticoagulant and recurrent miscarriages. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 145: 22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aly AS, Khandelwal M, Zhao J, Mehmet AH, Sammel MD, Parry S 2004. Neutrophils are stimulated by syncytiotrophoblast microvillous membranes to generate superoxide radicals in women with preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 190: 252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A, Jean-Pierre C, Kaur P, Rao P, Linhares IM, Skupski D, Witkin SS 2008. Heat shock protein-containing exosomes in mid-trimester amniotic fluids. J Reprod Immunol 79: 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atay S, Gercel-Taylor C, Suttles J, Mor G, Taylor DD 2011a. Trophoblast-derived exosomes mediate monocyte recruitment and differentiation. Am J Reprod Immunol 65: 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atay S, Gercel-Taylor C, Taylor DD 2011b. Human trophoblast-derived exosomal fibronectin induces pro-inflammatory IL-1β production by macrophages. Am J Reprod Immunol 66: 259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood HD, Park WW 1961. Embolism to the lungs by trophoblast. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 68: 611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig S, Lim JY, Fernandis AZ, Wenk MR, Kale A, Su LL, Biswas A, Vasoo S, Shui G, Choolani M 2013. Lipidomic analysis of human placental syncytiotrophoblast microvesicles in adverse pregnancy outcomes. Placenta 34: 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff FZ, Lewis DE, Simpson JL 2005. Cell-free fetal DNA in maternal blood: Kinetics, source and structure. Hum Reprod Update 11: 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buurma AJ, Penning ME, Prins F, Schutte JM, Bruijn JA, Wilhelmus S, Rajakumar A, Bloemenkamp KW, Karumanchi SA, Baelde HJ 2013. Preeclampsia is associated with the presence of transcriptionally active placental fragments in the maternal lung. Hypertension 62: 608–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosens I, Robertson WB, Dixon HG 1967. The physiological response of the vessels of the placental bed to normal pregnancy. J Pathol Bacteriol 93(2): 569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamley LW, Holland OJ, Chen Q, Viall CA, Stone PR, Abumaree M 2014. Review: Where is the maternofetal interface? Placenta 35: S74–S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Stone PR, McCowan LM, Chamley LW 2006. Phagocytosis of necrotic but not apoptotic trophoblasts induces endothelial cell activation. Hypertension 47: 116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Stone P, Ching LM, Chamley L 2009. A role for interleukin-6 in spreading endothelial cell activation after phagocytosis of necrotic trophoblastic material: Implications for the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia. J Pathol 217: 122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Ding JX, Liu B, Stone P, Feng YJ, Chamley L 2010. Spreading endothelial cell dysfunction in response to necrotic trophoblasts. Soluble factors released from endothelial cells that have phagocytosed necrotic shed trophoblasts reduce the proliferation of additional endothelial cells. Placenta 31: 976–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Guo F, Jin HY, Lau S, Stone P, Chamley L 2012a. Phagocytosis of apoptotic trophoblastic debris protects endothelial cells against activation. Placenta 33: 548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Huang Y, Jiang R, Teng Y 2012b. Syncytiotrophoblast-derived microparticle shedding in early-onset and late-onset severe pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 119: 234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Tong M, Wu M, Stone PR, Snowise S, Chamley LW 2013. Calcium supplementation prevents endothelial cell activation: Possible relevance to preeclampsia. J Hypertens 31: 1828–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua S, Wilkins T, Sargent I, Redman C 1991. Trophoblast deportation in pre-eclamptic pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 98: 973–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockell AP, Learmont JG, Smarason AK, Redman CW, Sargent IL, Poston L 1997. Human placental syncytiotrophoblast microvillous membranes impair maternal vascular endothelial function. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 104: 235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci G, Pesenti E, Molteni E, Lobbiani A, De Andreis C, Pariani S, Rossella F, Semprini AE, Simoni G 1993. Applicability of DNA isolated from syncytiotrophoblast vesicles to gene amplification and molecular analysis. Prenat Diagn 13: 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covone AE, Mutton D, Johnson PM, Adinolfi M 1984. Trophoblast cells in peripheral blood from pregnant women. Lancet 2(8407): 841–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronqvist T, Saljé K, Familari M, Guller S, Schneider H, Gardiner C, Sargent IL, Redman CW, Mörgelin M, Åkerström B, et al. 2014. Syncytiotrophoblast vesicles show altered micro-RNA and haemoglobin content after ex-vivo perfusion of placentas with haemoglobin to mimic preeclampsia. PLoS ONE 9: e90020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenne D, Thibault G, Guillaumin JM, Lacord M, Bardos P 1991. Syncytiotrophoblast plasma membrane inhibits membrane expression of activation markers on PHA-stimulated human lymphocytes. J Reprod Immunol 20: 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme-Axford E, Donker RB, Mouillet JF, Chu T, Bayer A, Ouyang Y, Wang T, Stolz DB, Sarkar SN, Morelli AE, et al. 2013. Human placental trophoblasts confer viral resistance to recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 12048–12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donker RB, Mouillet JF, Chu T, Hubel CA, Stolz DB, Morelli AE, Sadovsky Y 2012. The expression profile of C19MC microRNAs in primary human trophoblast cells and exosomes. Mol Hum Reprod 18: 417–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangsmyr L, Baranov V, Nagaeva O, Stendahl U, Kjellberg L, Mincheva-Nilsson L 2005. Cytoplasmic microvesicular form of Fas ligand in human early placenta: Switching the tissue immune privilege hypothesis from cellular to vesicular level. Mol Hum Reprod 11: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner C, Tannetta DS, Simms CA, Harrison P, Redman CW, Sargent IL 2011. Syncytiotrophoblast microvesicles released from pre-eclampsia placentae exhibit increased tissue factor activity. PLoS ONE 6: e26313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain SJ, Sacks GP, Sooranna SR, Sargent IL, Redman CW 2007. Systemic inflammatory priming in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia: The role of circulating syncytiotrophoblast microparticles. J Immunol 178: 5949–5956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami D, Tannetta DS, Magee LA, Fuchisawa A, Redman CW, Sargent IL, von Dadelszen P 2006. Excess syncytiotrophoblast microparticle shedding is a feature of early-onset pre-eclampsia, but not normotensive intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta 27: 56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guller S, Tang Z, Ma YY, Di Santo S, Sager R, Schneider H 2011. Protein composition of microparticles shed from human placenta during placental perfusion: Potential role in angiogenesis and fibrinolysis in preeclampsia. Placenta 32: 63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AK, Holzgreve W, Huppertz B, Malek A, Schneider H, Hahn S 2004. Detection of fetal DNA and RNA in placenta-derived syncytiotrophoblast microparticles generated in vitro. Clin Chem 50: 2187–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AK, Hasler P, Holzgreve W, Gebhardt S, Hahn S 2005a. Induction of neutrophil extracellular DNA lattices by placental microparticles and IL-8 and their presence in preeclampsia. Hum Immunol 66: 1146–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AK, Rusterholz C, Holzgreve W, Hahn S 2005b. Syncytiotrophoblast micro-particles do not induce apoptosis in peripheral T lymphocytes, but differ in their activity depending on the mode of preparation. J Reprod Immunol 68: 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AK, Rusterholz C, Huppertz B, Malek A, Schneider H, Holzgreve W, Hahn S 2005c. A comparative study of the effect of three different syncytiotrophoblast micro-particles preparations on endothelial cells. Placenta 26: 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AK, Holzgreve W, Hahn S 2008. Decrease in lipid levels of syncytiotrophoblast micro-particles reduced their potential to inhibit endothelial cell proliferation. Arch Gynecol Obstet 277: 115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund M, Stenqvist AC, Nagaeva O, Kjellberg L, Wulff M, Baranov V, Mincheva-Nilsson L 2009. Human placenta expresses and secretes NKG2D ligands via exosomes that down-modulate the cognate receptor expression: Evidence for immunosuppressive function. J Immunol 183: 340–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh AM, Tannetta D, Sargent I, Borup R, Nielsen FC, Redman C, Sorensen S, Hviid TV 2006. Effect of syncytiotrophoblast microvillous membrane treatment on gene expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. BJOG 113: 1270–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder BS, Tower CL, Forbes K, Mulla MJ, Aplin JD, Abrahams VM 2012a. Immune cell activation by trophoblast-derived microvesicles is mediated by syncytin 1. Immunology 136: 184–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder BS, Tower CL, Jones CJ, Aplin JD, Abrahams VM 2012b. Heightened pro-inflammatory effect of preeclamptic placental microvesicles on peripheral blood immune cells in humans. Biol Reprod 86: 103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland OJ, Linscheid C, Hodes HC, Nauser TL, Gilliam M, Stone P, Chamley LW, Petroff MG 2012. Minor histocompatibility antigens are expressed in syncytiotrophoblast and trophoblast debris: Implications for maternal alloreactivity to the fetus. Am J Pathol 180: 256–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller S, Ridinger J, Rupp AK, Janssen JW, Altevogt P 2011. Body fluid derived exosomes as a novel template for clinical diagnostics. J Transl Med 9: 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalfoun B, Degenne D, Crouzat-Reynes G, Bardos P 1986. Effect of human syncytiotrophoblast plasma membrane-soluble extracts on in vitro mitogen-induced lymphocyte proliferation. A possible inhibition mechanism involving the transferrin receptor. J Immunol 137: 1187–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M, Redman CW, Linton EA, Sargent IL 1998. Shedding of syncytiotrophoblast microvilli into the maternal circulation in pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 105: 632–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal J, Tkach M, Thery C 2014. Biogenesis and secretion of exosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 29C: 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kshirsagar SK, Alam SM, Jasti S, Hodes H, Nauser T, Gilliam M, Billstrand C, Hunt JS, Petroff MG 2012. Immunomodulatory molecules are released from the first trimester and term placenta via exosomes. Placenta 33: 982–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapaire O, Holzgreve W, Oosterwijk JC, Brinkhaus R, Bianchi DW 2007. Georg Schmorl on trophoblasts in the maternal circulation. Placenta 28: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Romero R, Lee YJ, Park IS, Park CW, Yoon BH 2012. Systemic inflammatory stimulation by microparticles derived from hypoxic trophoblast as a model for inflammatory response in preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 207: 337 e331–e338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, et al. 2004. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 350: 672–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok CA, Boing AN, Sargent IL, Sooranna SR, van der Post JA, Nieuwland R, Sturk A 2008a. Circulating platelet-derived and placenta-derived microparticles expose Flt-1 in preeclampsia. Reprod Sci 15: 1002–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok CA, Van Der Post JA, Sargent IL, Hau CM, Sturk A, Boer K, Nieuwland R 2008b. Changes in microparticle numbers and cellular origin during pregnancy and preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy 27: 344–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo SS, Ishibashi O, Ishikawa G, Ishikawa T, Katayama A, Mishima T, Takizawa T, Shigihara T, Goto T, Izumi A, et al. 2009. Human villous trophoblasts express and secrete placenta-specific microRNAs into maternal circulation via exosomes. Biol Reprod 81: 717–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew T.M 2014. Turnover of human villous trophoblast in normal pregnancy: What do we know and what do we need to know? Placenta 35(4): 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, Libermann TA, Morgan JP, Sellke FW, Stillman IE, et al. 2003. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest 111: 649–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerli M, May K, Hansson SR, Schneider H, Holzgreve W, Hahn S, Rusterholz C 2010. Feto-maternal interactions in pregnancies: Placental microparticles activate peripheral blood monocytes. Placenta 31: 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mincheva-Nilsson L, Nagaeva O, Chen T, Stendahl U, Antsiferova J, Mogren I, Hernestal J, Baranov V 2006. Placenta-derived soluble MHC class I chain-related molecules down-regulate NKG2D receptor on peripheral blood mononuclear cells during human pregnancy: A possible novel immune escape mechanism for fetal survival. J Immunol 176: 3585–3592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan MJ, McIntyre JA, Prior M, Warriner G, Faulk WP 1982. Identification of human trophoblast membrane antigens in maternal blood during pregnancy. Clin Exp Immunol 48: 279–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omatsu K, Kobayashi T, Murakami Y, Suzuki M, Ohashi R, Sugimura M, Kanayama N 2005. Phosphatidylserine/phosphatidylcholine microvesicles can induce preeclampsia-like changes in pregnant mice. Semin Thromb Hemost 31: 314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco AF, Jorgez CJ, Horne C, Marquez-Do DA, Chapman MR, Rodgers JR, Bischoff FZ, Lewis DE 2008. Membrane protected apoptotic trophoblast microparticles contain nucleic acids: Relevance to preeclampsia. Am J Pathol 173: 1595–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco AF, Jorgez CJ, Ramos-Perez WD, Popek EJ, Yu X, Kozinetz CA, Bischoff FZ, Lewis DE 2009. Placental release of distinct DNA-associated micro-particles into maternal circulation: Reflective of gestation time and preeclampsia. Placenta 30: 891–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pap E, Pallinger E, Falus A, Kiss AA, Kittel A, Kovacs P, Buzas EI 2008. T lymphocytes are targets for platelet- and trophoblast-derived microvesicles during pregnancy. Placenta 29: 826–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park WW 1975. Possible functions of nonvillous trophoblast. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 5: 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar A, Cerdeira AS, Rana S, Zsengeller Z, Edmunds L, Jeyabalan A, Hubel CA, Stillman IE, Parikh SM, Karumanchi SA 2012. Transcriptionally active syncytial aggregates in the maternal circulation may contribute to circulating soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 in preeclampsia. Hypertension 59: 256–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana S, Zoller M 2011. Exosome target cell selection and the importance of exosomal tetraspanins: A hypothesis. Biochem Soc Trans 39: 559–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana S, Yue S, Stadel D, Zoller M 2012. Toward tailored exosomes: The exosomal tetraspanin web contributes to target cell selection. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 44: 1574–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Stoorvogel W 2013. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 200: 373–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Record M, Carayon K, Poirot M, Silvente-Poirot S 2014. Exosomes as new vesicular lipid transporters involved in cell-cell communication and various pathophysiologies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1841: 108–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy A, Zhong XY, Rusterholz C, Hahn S, Holzgreve W, Redman CW, Sargent IL 2008. The effect of labour and placental separation on the shedding of syncytiotrophoblast microparticles, cell-free DNA and mRNA in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Placenta 29: 942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusterholz C, Holzgreve W, Hahn S 2007. Oxidative stress alters the integrity of cell-free mRNA fragments associated with placenta-derived syncytiotrophoblast microparticles. Fetal Diagn Ther 22: 313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabapatha A, Gercel-Taylor C, Taylor DD 2006. Specific isolation of placenta-derived exosomes from the circulation of pregnant women and their immunoregulatory consequences. Am J Reprod Immunol 56: 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon C, Ryan J, Sobrevia L, Kobayashi M, Ashman K, Mitchell M, Rice GE 2013. Exosomal signaling during hypoxia mediates microvascular endothelial cell migration and vasculogenesis. PLoS ONE 8: e68451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmorl G 1893. Pathologisch-Anatomische Untersuchungen Uber Puerperal-Eklampsie. Verlag von FC Vogel, Leipzig, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Shen F, Wei J, Snowise S, DeSousa J, Stone P, Viall C, Chen Q, Chamley L 2014. Trophoblast debris extruded from preeclamptic placentae activates endothelial cells: A mechanism by which the placenta communicates with the maternal endothelium. Placenta 35: 839–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smarason AK, Sargent IL, Starkey PM, Redman CW 1993. The effect of placental syncytiotrophoblast microvillous membranes from normal and pre-eclamptic women on the growth of endothelial cells in vitro. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 100: 943–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southcombe J, Tannetta D, Redman C, Sargent I 2011. The immunomodulatory role of syncytiotrophoblast microvesicles. PLoS ONE 6: e20245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenqvist AC, Nagaeva O, Baranov V, Mincheva-Nilsson L 2013. Exosomes secreted by human placenta carry functional Fas ligand and TRAIL molecules and convey apoptosis in activated immune cells, suggesting exosome-mediated immune privilege of the fetus. J Immunol 191: 5515–5523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannetta DS, Dragovic RA, Gardiner C, Redman CW, Sargent IL 2013. Characterisation of syncytiotrophoblast vesicles in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia: Expression of Flt-1 and endoglin. PLoS ONE 8: e56754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DD, Akyol S, Gercel-Taylor C 2006. Pregnancy-associated exosomes and their modulation of T cell signaling. J Immunol 176: 1534–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Than NG, Abdul Rahman O, Magenheim R, Nagy B, Fule T, Hargitai B, Sammar M, Hupuczi P, Tarca AL, Szabo G, et al. 2008. Placental protein 13 (galectin-13) has decreased placental expression but increased shedding and maternal serum concentrations in patients presenting with preterm pre-eclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Virchows Archiv 453: 387–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault G, Degenne D, Girard AC, Guillaumin JM, Lacord M, Bardos P 1991. The inhibitory effect of human syncytiotrophoblast plasma membrane vesicles on in vitro lymphocyte proliferation is associated with reduced interleukin 2 receptor expression. Cell Immunol 138: 165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault G, Degenne D, Lacord M, Guillaumin JM, Girard AC, Bardos P 1992. Inhibitory effect of human syncytiotrophoblast plasma membrane vesicles on Jurkat cells activated by phorbol ester and calcium ionophore. Cell Immunol 139: 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolosa JM, Schjenken JE, Clifton VL, Vargas A, Barbeau B, Lowry P, Maiti K, Smith R 2012. The endogenous retroviral envelope protein syncytin-1 inhibits LPS/PHA-stimulated cytokine responses in human blood and is sorted into placental exosomes. Placenta 33: 933–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas A, Zhou S, Ethier-Chiasson M, Flipo D, Lafond J, Gilbert C, Barbeau B 2014. Syncytin proteins incorporated in placenta exosomes are important for cell uptake and show variation in abundance in serum exosomes from patients with preeclampsia. FASEB J 28: 3703–3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Dadelszen P, Hurst G, Redman CW 1999. Supernatants from co-cultured endothelial cells and syncytiotrophoblast microvillous membranes activate peripheral blood leukocytes in vitro. Hum Reprod 14: 919–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]