Abstract

Purpose

Perinatal health disparities are of particular concern with pregnant urban African American adolescents who have high rates of stress and depression during pregnancy, higher rates of adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, and many barriers to effective treatment. The purpose of this study was to explore pregnant urban African American teenagers’ experience of stress and depression and examine their perceptions of adjunctive non-pharmacologic management strategies, such as yoga.

Methods

This community-based qualitative study utilized non-therapeutic focus groups to allow for exploration of attitudes, concerns, beliefs and values regarding stress and depression in pregnancy and non-pharmacologic management approaches, such as mind-body therapies and other prenatal activities.

Findings

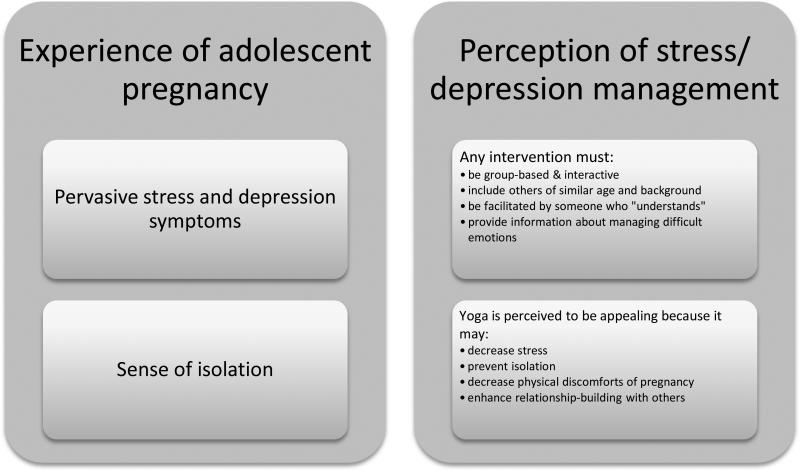

The sample consisted of pregnant African-American low-income adolescents (n=17) who resided in a large urban area in the United States. The themes that arose in the focus group discussions were: (1) stress and depression symptoms are pervasive in daily life; (2) participants felt a generalized sense of isolation; (3) stress/depression-management techniques should be group-based, interactive, and focused on the specific needs of teenagers; (4) yoga is an appealing stress-management technique to this population.

Conclusions

The findings from this study suggest that pregnant urban adolescents are highly stressed, they interpret depression-like symptoms to be signs of stress, they desire group-based, interactive activities, and they are interested in yoga classes for stress/depression management and relationship-building. It is imperative that healthcare providers and researchers focus on these needs, particularly when designing prevention and intervention strategies.

Introduction

Perinatal health disparities are of particular concern with African American (AA) and low-socioeconomic status (SES) women who have higher rates of major or minor depression during pregnancy, higher rates of adverse outcomes, and more barriers to effective treatment than their Caucasian and well-insured counterparts (Luke et al., 2009; Melville, Gavin, Guo, Fan, & Katon, 2010). Particularly for pregnant AA adolescents, depression and stress can be pervasive and debilitating and may increase the risk for poor outcomes, such as obstetric complications, multiple pregnancies, and cognitive/developmental delays in the children (Siegel & Brandon, 2014). Despite availability of antidepressant medications and psychotherapies, pregnant women with depression symptoms remain largely undertreated due to concerns with teratogenic effects and maternal side effects of antidepressant medications as well as costs and stigma associated with seeking depression care (Andrews, Kornstein, Halberstadt, Gardner, & Neale, 2011; Bennett, Marcus, Palmer, & Coyne, 2010; L. S. Cohen et al., 2006; Jesse, Dolbier, & Blanchard, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2006; Warden et al., 2010; Yonkers et al., 2009). Because of these concerns with the standard medical management and because considerable evidence points to the role of maladaptive stress responses in depression, non-pharmacologic stress management techniques must be evaluated as adjunctive interventions for prenatal depression.

Prenatal depression is a major public health concern due to the association with poor maternal, obstetric, and neonatal/child health outcomes (Kessler et al., 2003). Pregnancy during adolescence places the teenager at high risk for mental illness, such that the pregnant teenager is twice as likely to experience depression and/or suicidality compared to her non-pregnant peers (Mollborn & Morningstar, 2009; Siegel & Brandon, 2014). In adult populations, it has been estimated that close to 13% of all pregnant women have an episode of major depression and up to 20% of pregnant women experience depressive symptoms (Davalos, Yadon, & Tregellas, 2012). In adolescent populations, findings of research studies suggest a similar or higher prevalence of major depressive disorder during pregnancy, as well as high rates of comorbid substance use and anxiety disorders (Siegel & Brandon, 2014). Both adolescent and adult women with prenatal depression are more likely to experience postpartum depression, suicide, substance abuse, pregnancy complications, and inadequate prenatal care (Beck, 2001; Kornstein, 2001; Yonkers et al., 2009). Depression in pregnancy is associated with preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and low birth weight, particularly in women of lower SES, in AA women, in those without strong social support, and in those who are under- or uninsured (Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S,Katon WJ, 2010; Sexton et al., 2012; Witt, Wisk, Cheng, Hampton, & Hagen, 2011). A large population-based cohort study of all births in the United States between 1995 and 2004 revealed that young adolescent pregnancies are associated with inadequate prenatal care, are most likely to occur in minorities, and are more likely to be associated with neonatal and obstetric complications (Malabarey, Balayla, Klam, Shrim, & Abenhaim, 2012). Furthermore, adolescent motherhood as well as the presence of perinatal stress and depression is associated with poor maternal-fetal/child attachment and poor parenting behaviors, which can significantly impact the development of the child (V. Glover, 2014b; Riva Crugnola, Ierardi, Gazzotti, & Albizzati, 2014). Perinatal health disparities are of particular concern with AA and low-SES women who have significant stress vulnerabilities as well as experience higher rates of major or minor depression during pregnancy, higher rates of adverse outcomes, and more barriers to effective treatment than their Caucasian and well-insured counterparts (Luke et al., 2009; Melville et al., 2010). Although pregnancy increases the chance of receiving attention from a healthcare provider, many pregnant women with depressive symptoms receive inadequate treatment for a variety of reasons, including lack of trust, concerns with stigma, and concerns with the “usual care” (psychotropic medications and/or psychotherapy), such as teratogenic effects, maternal side effects, and cost issues (Andrews et al., 2011; Bennett et al., 2010; L. S. Cohen et al., 2006; Jesse et al., 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2006; Warden et al., 2010; Yonkers et al., 2009).

This qualitative study was designed to evaluate pregnant AA adolescents’ perceptions of depression and stressful experiences. Additionally, the study assessed feasibility and acceptability of adjunctive/complementary non-pharmacologic stress and depression management strategies (e.g. mindfulness, yoga, walking, guided imagery, centering pregnancy groups, among others) for this underserved population, a group which has significant stress vulnerability and high rates of prenatal depression and is thus at high risk of poor pregnancy/neonatal health outcomes.

Research Methods/Design

With an overarching goal of developing a knowledge base regarding adjunctive stress and depression management strategies informed by underserved (AA and low-SES) pregnant adolescent community members, our research aims were as follows: (a) generate descriptions about perceived stress and depression potentially experienced by underserved pregnant adolescents in the community; (b) determine what types of adjunctive therapies (e.g. yoga, other mind-body therapies) for stress/depression management would be of interest and acceptable to underserved pregnant adolescents; and, (c) examine effective strategies for the recruitment and retention of underserved pregnant adolescents in a future intervention study. To do so, we conducted qualitative interviews using non-therapeutic focus groups, known to be helpful in exploratory research for allowing researchers to assess how groups of individuals collectively think about a topic and to explore their knowledge of and experiences with that topic (Doody, Slevin, & Taggart, 2013a; Doody, Slevin, & Taggart, 2013b). The focus groups were structured to allow for exploration of attitudes, concerns, beliefs and values regarding stress and depression in pregnancy and adjunctive non-pharmacologic management approaches, such as mind-body or other potential complementary therapies (e.g. yoga, tai chi, mindfulness, meditation, prayer, walking, dancing, among others). In addition, questions in the focus groups were asked to ascertain ideas and beliefs about recruitment and retention of underserved pregnant women in research studies.

Sample, Participants, Recruitment

This study was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board (IRB). The sample consisted of pregnant low-income AA adolescents residing in an urban area. Participants were recruited predominantly through the local health department's women's health and teen pregnancy programs. IRB-approved flyers were distributed to potential participants. Interested individuals who met the following inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the focus group: (a) currently pregnant; (b) age 14-21; (c) self-identify as AA; (d) low-SES (defined by eligibility for Women's, Infants, and Children program [WIC] in Virginia). Eligible individuals who expressed interest in the study were provided with information about the study and, if age 18 or older, engaged in the informed consent process. Adolescent participants who were minors (ages 14-17) had a parent/ guardian who provided permission for the participant taking part in the research and the adolescent provided assent to participate. All consent and assent documents were written at a 6th grade reading level.

Data Collection

All focus group sessions were moderated by one investigator (PK) using a semi-structured format with questions to direct and facilitate discussion. Participants were asked to use initials only and not names during the sessions. Open-ended questions were used to explore participants’ experiences with stress and depression. Questions were also asked to help ascertain participants’ thoughts about various non-pharmacologic stress and depression management activities and their perceptions of effective strategies for recruitment and retention in a future intervention study.

Data Analysis

All focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed. The data were analyzed independently by the two authors through content analysis based on descriptive qualitative methodology with phenomenological overtones (Sandelowski, 2000); the collected data were analyzed in the manner of a hermeneutic circle (Agar, 1986; M. Cohen, Kahn, & Steeves, 2000). Briefly, the step-wise manner we used included reading all transcripts from interviews to get an overall view of the data, identifying strips that may be important, re-reading all of the data to confirm that the strips were appropriately derived from the context, grouping strips into categories based upon similarities, re-reading all of the data, and, finally, organizing the categories into themes to be subsequently examined and interpreted. To ensure rigor in methodology and study findings, we took the following steps: 1) inter-rater reliability was established through independent coding by the authors and coding was compared for agreement; 2) peer debriefing was used to ensure that the data analysis was unbiased and logical, in which colleagues unrelated to the study were asked to review the data and confirm themes; and 3) dependability of the data was established by including direct participant quotations to support themes (Sandelowski, 1986).

Results

Seventeen pregnant teenagers participated in the focus groups. The mean age of participants was 17.5±1.3. All participants were currently enrolled in high school and were not married. Fifty-three percent (n=9) had a part-time job. Four key themes arose from the focus group discussions: (1) stress and depression symptoms are pervasive in the participants’ daily life; (2) participants felt a generalized sense of isolation; (3) management interventions should be group-based and address specific needs of teenagers; and (4) yoga is an appealing intervention. These four themes were derived from comments shared by almost every single focus group participant. Quotes from participants are presented to support and illustrate these themes. Figure 1 summarizes these themes.

Figure 1.

Themes

Theme #1: Stress and Depression-like Symptoms are Pervasive

Pregnancy related stress was on the forefront of many participants’ minds. Stress and uncertainties about what constitutes normal pregnancy or the health of their baby were common, as exemplified in one participant's comment that “I feel like everybody got so many pregnancy myths it be scary” and another participant's statement that “I know I worry all the time... what if something bad happened or I sleep on my stomach or anything like that.” The majority of participants seemed extremely stressed about whether they will be able to support themselves or finish school. This stress and concurrent anxiety about the future was elaborated by one young woman who said: “I worry about after [I deliver]. I feel like this the easy part is carrying the baby, [but later] you gotta go back to school and you have to worry about thinking about the baby all day and not be focused.” Reassurance from parents seemed to not be helpful: “my mom used to tell me ‘don't worry about it’ but you worry about things.”

When asked whether they ever feel depressed, many participants were somewhat confused by the question. However, when the interviewer asked if they ever feel blue or feel overwhelmed, most participants emphatically responded that they do feel that way most of the time. Many participants articulated their experience of stress with descriptions of depression-like symptoms, such as crying all the time, difficulty finding pleasure in activities that typically would be enjoyable, generalized irritability, and difficulties getting out of bed. One participant stated that “I just start crying for no reason” and another stated “I just wanna sleep all the time”, and multiple other participants echoed those experiences. An undercurrent of irritability seemed pervasive, as reflected in one participant's comment that “you eat, you sleep and you wake up mad.”

Theme #2: Pregnancy during Adolescence is Isolating

Many participants consistently reported a generalized sense of isolation during their pregnancy, despite attention from parents, healthcare providers, and others. They expressed concern that this isolation reinforces their feelings of stress and depression, stemming largely from perceived lack of social support. One participant clearly stated: “I think that's where my stress comes from- feeling like I have to do everything by myself.” Lack of involvement of the baby's father was a particular stressor and seemed to contribute to the feelings of isolation. Many participants would “cry every day just because of him” because of concerns whether the baby's father would “step up” and be involved. Participants expressed feelings of sadness that the baby's father was not attending obstetrician appointments. One participant described how she questioned the baby's father: “I used to get mad when school was going on because I... got these doctor appointments... and [I said] ‘you telling me you can't make it to one doctor's appointment?’” This seemed to be very stressful to participants when they reflected upon the future and whether they would receive any assistance, as one young woman stated: “They [the baby's father] can just get up and go...They be like ‘I didn't make that baby, you made that baby.’ So I think that's something my stress comes from.” In addition, participants felt that the baby's father and other friends tended to go out and have fun without them. One participant described feeling left out: “And then I call my child's father to talk, but he be like ‘oh I'm at the club.’ I be like ‘what? You at the club?’ and I get more angry.” Another participant summarized this feeling of isolation in her statement that “I think that's depressing because you had a life before you got pregnant, then you get pregnant and you can't do much.” As a result of this perceived isolation and lack of predictable social support, many participants seemed to pull inward and decided they could not depend upon anyone. One young woman said, “It's the baby and myself right now. It's not easy” and another clearly stated, “I don't depend on nobody to do nothing.” Another participant summarized these feelings of sadness and isolation, saying “[I] be feeling like I ain't got nobody to talk to... everybody be leaving me.”

Another isolating factor for the participants seemed to be a feeling that very few people can understand their experience and thus provide emotional support. Participants perceived that family members, the baby's father, non-pregnant friends, teachers, and healthcare providers could not adequately provide support, because, as one participant stated “it's easier on them... they are not the ones that are pregnant and they don't understand how you feel.” Participants described a sense of irritation with how their mothers or women in their churches would give advice about various topics, as one participant elaborated: “That make me so mad that they think they know what you feel like. They ain't pregnant but they think they're so right.” Participants consistently expressed concern that they could only seek support from other women who were pregnant or who had been pregnant when they were young because, otherwise, “people don't really understand your situation so they can't really help you.”

Theme #3: Group-based Intervention Focused on Specific Needs

Participants expressed a great need for stress and depression-management interventions among pregnant adolescents. However, numerous caveats were given about the ideal content and style of the interventions which should best meet the needs of pregnant adolescents:

First, participants stated that the interventions should be group-based and interactive. Participants expressed interest in an interactive group setting, as revealed by enthusiastic agreement by many of the young women after the following statements by one participant: “I just like to talk to people” and “I like hands on [activities].” Another participant suggested that the group-based setting would be helpful for the relationship-building component to decrease a sense of isolation: “[It would be good to develop] relationships with people who are going through the same thing you are, and they're your age.”

Second, participants suggested that the group should consist of other pregnant girls their own age and ideally from a similar background. For example, a few participants had experience with Centering Pregnancy groups which they did not enjoy because they felt they could not identify with others in the group who were older, were accompanied by husbands, and were obviously of different socioeconomic status. As one participant stated, “they [other people in the group] were all grown. Then you be [embarrassed] and all saying ‘oh I'm a child and I got a baby on the way’” and another participant chimed in, “and they're doing things as a family and you ain't.”

Third, participants suggested that the group-based intervention should be facilitated by someone with whom they could relate and wouldn't be embarrassed around. For example, many participants expressed body image concerns and stated that they wouldn't want someone to lead the class who didn't understand pregnancy; one participant stated: “I move one way, my stomach go the other way”. Another participant stated, “if you bring in a 42 year old lady... I'm gonna look at her like, ‘what you know [about] depression?’”, which suggests that a group facilitator should be someone with whom pregnant adolescents can relate and who is perceived to understand their experience.

Fourth, participants expressed interest in learning more about what to expect during pregnancy with regards to managing difficult emotions. While some participants acknowledged the importance of learning about how to take care of the baby, many others emphasized the importance of learning how to cope with stress and feelings of depression, both during pregnancy and postpartum. One participant stated, “in classes I think they should talk about stuff that could prepare you just in case you get depressed, ‘cause it can hit you. You wake up and find 2 minutes later you just... be cryin’” Another participant echoed this sentiment, stating that it would be helpful if a group facilitator would “talk about stuff like that to get you prepared” for emotional coping once the baby is born. Participants expressed a desire for knowledge about the difference between normal feelings of “blues” and depression so that, as one participant suggested, she would know how to seek help “before I get depressed.”

Theme #4: Yoga is an Appealing Intervention

The interviewer asked participants about their interest in numerous types of adjunctive/ mind-body modalities (e.g. walking, breathing techniques, guided imagery/ meditation, tai chi, yoga, dance, centering pregnancy groups). Overwhelmingly, participants were most interested in yoga as a stress/depression intervention. Many participants had either seen yoga in the media or had experienced it themselves, whereas they had not experienced or were not interested in many of the other modalities. The possible benefits or appealing aspects of yoga were numerous:

First, participants perceived yoga to be helpful for stress, despite the fact that most of the young women had never personally experienced a yoga class. One participant expressed the possible benefit for herself and her baby: “I think it would bring on a happier pregnancy and a healthier baby. Like, I'm stressed out, so I'm going to yoga class.” Another participant stated that it would be helpful for quieting her mind from anxieties: “For the little hour that you do it, you not thinking about anything else.” A participant who had attended a yoga class explained her experience and the possible benefits this way: “It's a stress reliever... it's so quiet in that little room...Yeah it is a stress reliever...the person's voice calms you down.”

Second, participants suggested that yoga classes would be helpful for combating feelings of isolation. Participants clearly stated that being in a group setting with other pregnant girls would be helpful because “you know you're not by yourself” and “you can find new friends in the group.” One young woman suggested that yoga class could be particularly fun because she and her pregnant friends would all attend together “like a support system.” Another participant felt it would be helpful to simply get out of the house when one is feeling blue because otherwise, “I don't got nothing to do but doctor appointments and parenting classes.”

Third, participants suggested that yoga might be helpful for some of the physical aspects of pregnancy. Some participants stated that they heard yoga could help with back pain and labor pain. Another participant, who was approaching 40 weeks gestational age, suggested she would certainly do yoga “if it will help him [the baby] come out.” Another participant thought that the group setting of a yoga class would be a good opportunity for discussing what to expect during the pregnancy.

Of note, not every participant was as enthusiastic about yoga as the majority of the group. Some participants expressed concern about the ability of their pregnant bodies to do the movements they perceived were required in yoga. For example, some of the negative comments from two participants were that “it don't do nothing, you just sit there” or “it's too quiet... that's gonna irritate me”. Another participant was concerned that a non-pregnant teacher would not understand her needs, stating “if they don't have a big stomach like me, and they're doing yoga, like, how am I supposed to do yoga?” In opposition to this sentiment, however, another participant felt she would be reassured because in a pregnancy-specific yoga class, the instructor would “consider that you're pregnant” and could therefore adapt the movements according to specific needs.

In summary, the majority of the participants were largely positive about the concept of yoga during pregnancy and many echoed the general statement of one young woman who suggested that people should have an open mind and “just try something new.” Participants offered numerous suggestions for making yoga classes appealing and accessible for pregnant AA urban teenagers, such as “make it sound really fun [in advertisements]”, offer classes at a location on a bus line or at local high schools, “show many races [in advertisements]”, and offer refreshments. Many participants reiterated the importance of encouraging the women in a yoga class to talk and develop “relationships with people” during class. One participant suggested that the relationship-development would be so important even beyond pregnancy and that yoga classes should be offered into the postpartum period:

I don't think [classes] should just stop once the 12 weeks over ‘cause, like, you bonded with these people that you were in there for 12 weeks so maybe you can do it and like [bring] the babies or something there afterwards. Because you don't want to just stop and be like ‘oh I'm never gonna see these people again.’ Cause you know you make connections, so maybe you can bring the babies and all that...yeah, they'll be playing with them and we can still be doing our yoga.

Discussion

The findings from this study suggest that pregnant urban AA teenagers are highly stressed and they interpret depression-like symptoms to be signs of stress. As is typical of this developmental period, the teenagers perceived that they are alone in their stress and fears about the future. The participants expressed a desire for group-based, interactive activities that would meet their specific needs, such as information and strategies for managing difficult emotions and activities which provide stress-relief and social support.

Pregnant adolescents in this study were faced with stressors and depressive symptoms affecting their pregnancy and daily life. The current body of literature suggests that low income women with unexpected pregnancy are more prone to high level of stress, depression and anxiety (Zachariah, 2009). Siegel and Brandon (2014) in a recent review of the literature reported that the rates of perinatal depressive symptoms in adolescents are higher than pregnant adults (Siegel & Brandon, 2014). Negative emotional and behavioral responses are mostly inexorable when adolescents are faced with unexpected or undesired pregnancy (Braine, 2009; Perez-Lopez, Perez-Roncero, & Lopez-Baena, 2010). Considering adolescents are more vulnerable to poor pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight, substance use, and high school dropout, the pervasiveness of these problems are a major public health concern and require immediate attention (Diego et al., 2009; V. Glover, 2014a; Li, Liu, & Odouli, 2009).

Adolescence is a transitional stage between childhood and adulthood with marked physiological and emotional changes. During this developmental stage, adolescents experience notable hormonal and physical changes making them emotionally vulnerable. Although their self-regulation may not be well developed, they experience increased risk taking behaviors coupled with peer influences. Further, they experience greater sense of independence and detachment from family guidance. Therefore, unexpected life event such as pregnancy during adolescence may lead to significant stress, loneliness, and helplessness (Furman, McDunn, & Young, 2009; Steinberg, 2004).

This qualitative study identified that participants felt isolated and reported frequent depressive symptoms. They felt isolated by their partners, peers and the society and often experienced depressive symptoms. The rate of adolescent perinatal depression in some populations is reported as 37% or higher (Birkeland, Thompson, & Phares, 2005; McGuinness, Medrano, & Hodges, 2013). However, studies suggest that social support is associated with fewer perinatal depressive symptoms and adolescents with social support demonstrated resilience (Hudson, Elek, & Campbell-Grossman, 2000; McGuinness et al., 2013; Panzarine, Slater, & Sharps, 1995; Salazar-Pousada, Arroyo, Hidalgo, Perez-Lopez, & Chedraui, 2010; Stevenson, Maton, & Teti, 1999; Turner, Grindstaff, & Phillips, 1990). Although the mechanism for this association is unclear, studies suggest that depressive symptoms are mitigated by the quality of support and their perception and level of satisfaction with the support (Panzarine et al., 1995). Furthermore, depression may mediate the association between social support and parenting skills (Angley, Divney, Magriples, & Kershaw, 2014), which has a significant impact on the adolescent's child. Although studies have identified parental support to be an important factor, support from peers and providers were reported to be associated with lower postpartum depression (Logsdon, Ziegler, Hertweck, & Pinto-Foltz, 2008; Milan et al., 2007).

Findings from the current study suggested that adolescents prefer group interventions and reported that yoga as an appealing method that has the potential to engage pregnant adolescents. Incorporating gentle physical activity, relaxation, and breathing techniques into one integrative practice, yoga has garnered recent attention as a promising, innovative, and potentially cost-effective complementary therapy for depression (Battle, Uebelacker, Howard, & Castaneda, 2010; Jain et al., 2007; Jorm, Morgan, & Hetrick, 2008; Mead et al., 2009; Rimer et al., 2012). The use of adjunctive therapies, such as yoga, has become increasingly popular in pregnancy, particularly for the relief of stress and pregnancy-related complaints (Adams et al., 2009). The participants in this study expressed a desire to learn about managing emotional needs of pregnancy and postpartum; of note, prenatal yoga classes in the United States often include this type of content in conjunction with the yoga breathing, movements, and relaxation practices (Kinser & Williams, 2008). The lived experience of women or adolescents who have used yoga therapies remains largely unexplored (Adams et al., 2009). The few studies conducted on yoga specifically for prenatal depression are encouraging (Beddoe, Paul Yang, Kennedy, Weiss, & Lee, 2009; Field et al., 2012; Narendran, Nagarathna, Narendran, Gunasheela, & Nagendra, 2005). However, to the knowledge of the authors this study, there are no studies that have examined the acceptability and its relative effectiveness for perinatal depression in adolescents or among inner city racially diverse pregnant adolescents.

In addition to the breathing exercises, mild physical activity and relaxation techniques, yoga may allow participants to develop strong cohesion and social support (Battle et al., 2010; Jain et al., 2007; Jorm et al., 2008; Mead et al., 2009; Rimer et al., 2012). Prenatal yoga classes may be appealing to adolescents due to the capacity for relationship-building, such that most prenatal yoga classes facilitate both formal and informal discussions during and after classes (Kinser & Williams, 2008). Of consideration, in our previous study of depressed women who participated in a yoga intervention, yoga was found to be helpful related to the sense of connectedness, or sense of self in the world, and shared experiences that occur independent of dialogue (Kinser, Bourguignon, Whaley, Hauenstein, & Taylor, 2013; Kinser, Bourguignon, Taylor, & Steeves, 2013). Of consideration for future research, studies should evaluate whether yoga is most “engaging” to youth related to the direct social support or the indirect enhancements in social connectedness.

Although the qualitative focus of this study provided rich information about adolescents experiences regarding perinatal stress, depression and their preferred method of intervention, it had few limitations. First, this study did not capture parental or partner's perspective regarding these issues and treatment options. Parents and partners may often be partially or fully responsible in deciding treatment choices. Understanding their perspective would have provided useful information to fully explore intervention choices for adolescents. Second, due to its qualitative nature, the frequency of themes identified in this study may not be representative. Third, it is possible that, among underserved adolescents, yoga is perceived as class-aspirational (an activity typically performed by higher socioeconomic status individuals); further research is warranted to evaluate this as a possible factor. Finally, this study did not address possible differences between younger and older adolescents. Due to differences in developmental stages and levels of maturity, treatment choices may differ by age.

Implications for Practice

This study has unveiled information that may have important practical implication. It sheds some light on the magnitude of the problem of depression and stress among inner city pregnant adolescents. Study participants reported experiencing high levels of stress and exhibited depression-like symptoms. Furthermore, these inner city participants interpreted depression-like symptoms to be signs of stress. Although health care providers use validated screening tools to diagnose depression, it is important for providers to be aware of the potential meaning of the term in this population. Healthcare providers and researchers should be aware of the specific needs of teenagers for stress/depression management, including their desire for group-based settings, interactive activities which enhance social support and provide strategies for managing difficult emotions, and their interest in yoga and similar adjunctive interventions.

In addition, researchers and healthcare providers may consider incorporating some of the suggestions by participants for making yoga classes appealing and accessible for urban pregnant adolescents. These suggestions included: using advertisements demonstrating racial/ethnic diversity, offering classes at local high schools or on bus-lines, encouraging relationship-building during the classes, weaving education about managing difficult emotions into the yoga class, and offering continued classes during the postpartum period. Of great relevance to the findings of this study, many prenatal yoga classes currently incorporate a group-based discussion at the beginning or end of classes; this practice should continue in order to facilitate a sense of social support or connectedness, addressing the specific needs of pregnant adolescents.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated adolescents’ perception and preference for group-based interventions which prevent or intervene with stress and depression during pregnancy. It was evident that adolescents were somewhat familiar with yoga and favored a yoga intervention to overcome and manage their stress. Information identified in this study could be used to improve and strengthen currently available intervention strategies offered to adolescents. It is imperative that healthcare providers and researchers focus on the multiple needs of this population, particularly when designing prevention and intervention strategies.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by VCU School of Nursing intramural funding, supported by P30 NR011403 (Grap, PI), Center of Excellence for Biobehavioral Approaches to Symptom Management; National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH.

Biography

Patricia Kinser, PhD, WHNP-BC, RNa

Dr. Kinser's program of research focuses on stress and depression management in women across the lifespan, with a focus on the biobehavioral effects of psychobehavioral and mind-body interventions on health outcomes and health behaviors for women and their families; gene-environment interactions (epigenetics) as related to stress and depression in women and their families; the intersection of research and clinical care regarding the promotion of positive health behaviors & interventions for mental and physical wellness.

Saba Masho, MD, MPH, DrPHb Dr. Masho's program of research focuses on maternal and child health particularly perinatal health and research related to poor birth outcomes, stress, obesity; health disparities; and provision of comprehensive care to under-served pregnant women; research related to women in violence, particularly sexual, domestic and youth violence; program evaluation and surveillance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams J, Lui C, Sibbritt D, Broom A, Wardle J, Homer C, Beck S. Women's use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy: A critical review of the literature. Birth. 2009;36(3):237–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00328.x. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agar M. Speaking of ethnography. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews PW, Kornstein SG, Halberstadt LJ, Gardner CO, Neale MC. Blue again: Perturbational effects of antidepressants suggest monoaminergic homeostasis in major depression. Frontiers in Psychology. 2011;2:159. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00159. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angley M, Divney A, Magriples U, Kershaw T. Social support, family functioning and parenting competence in adolescent parents. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1496-x. doi:10.1007/s10995-014-1496-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle CL, Uebelacker LA, Howard M, Castaneda M. Prenatal yoga and depression during pregnancy. Birth. 2010;37(4):353–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00435_1.x. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00435_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: An update. Nursing Research. 2001;50(5):275–285. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beddoe AE, Paul Yang CP, Kennedy HP, Weiss SJ, Lee KA. The effects of mindfulness-based yoga during pregnancy on maternal psychological and physical distress. JOGNN - Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2009;38(3):310–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IM, Marcus SC, Palmer SC, Coyne JC. Pregnancy-related discontinuation of antidepressants and depression care visits among medicaid recipients. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.) 2010;61(4):386–391. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.4.386. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.61.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland R, Thompson JK, Phares V. Adolescent motherhood and postpartum depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology : The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division. 2005;5334(2):292–300. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3402_8. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3402_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braine T. Adolescent pregnancy: A culturally complex issue. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009;87(6):410–411. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.020609. doi:S0042-96862009000600005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Kahn D, Steeves R. Hermeneutic phenomenological research: A practical guide for nurse researchers. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, Nonacs R, Newport DJ, Viguera AC, Stowe ZN. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295(5):499–507. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.5.499. doi:10.1001/jama.295.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos DB, Yadon CA, Tregellas HC. Untreated prenatal maternal depression and the potential risks to offspring: A review. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2012;15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0251-1. doi:10.1007/s00737-011-0251-1; 10.1007/s00737-011-0251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C, Gonzalez-Quintero VH. Prenatal depression restricts fetal growth. Early Human Development. 2009;85(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.07.002. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody O, Slevin E, Taggart L. Focus group interviews in nursing research: Part 1. British Journal of Nursing. 2013a;22(1):16–19. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2013.22.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody O, Slevin E, Taggart L. Preparing for and conducting focus groups in nursing research: Part 2. British Journal of Nursing. 2013b;22(3):170–173. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2013.22.3.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, Medina L, Delgado J, Hernandez A. Yoga and massage therapy reduce prenatal depression and prematurity. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2012;16(2):204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2011.08.002. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, McDunn C, Young B. Peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Implications for the development and maintenance of depression in adolescents. In: Allen N, Sheeber L, editors. Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2009. pp. 299–317. [Google Scholar]

- Glover V. Maternal depression, anxiety and stress during pregnancy and child outcome; what needs to be done. Best Practice & Research.Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2014a;28(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.017. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover V. Maternal depression, anxiety and stress during pregnancy and child outcome; what needs to be done. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2014b;28(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.017. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1012–1024. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson DB, Elek SM, Campbell-Grossman C. Depression, self-esteem, loneliness, and social support among adolescent mothers participating in the new parents project. Adolescence. 2000;35(139):445–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Shapiro S, Swanick S, Roesch S, Mills P, Bell I, Schwartz G. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33:11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesse DE, Dolbier CL, Blanchard A. Barriers to seeking help and treatment suggestions for prenatal depressive symptoms: Focus groups with rural low-income women. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2008;29(1):3–19. doi: 10.1080/01612840701748664. doi:10.1080/01612840701748664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Morgan AJ, Hetrick SE. Relaxation for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) 2008;4(4):CD007142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007142.pub2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007142.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas K, Wang P. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(3):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Bourguignon C, Taylor AG, Steeves R. ‘A feeling of connectedness’: Perspectives on a gentle yoga intervention for women with major depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2013;34(6):402–411. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.762959. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.762959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Bourguignon C, Whaley D, Hauenstein E, Taylor AG. Feasibility, acceptability, and effects of gentle Hatha yoga for women with major depression: Findings from a randomized controlled mixed-methods study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2013;27(3):137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.01.003. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser P, Williams C. Prenatal yoga. guidance for providers and patients. Advance for Nurse Practitioners. 2008;16(5):59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornstein SG. The evaluation and management of depression in women across the life span. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 24):11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Liu L, Odouli R. Presence of depressive symptoms during early pregnancy and the risk of preterm delivery: A prospective cohort study. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England) 2009;24(1):146–153. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den342. doi:10.1093/humrep/den342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon MC, Ziegler C, Hertweck P, Pinto-Foltz M. Testing a bioecological model to examine social support in postpartum adolescents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship : An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing / Sigma Theta Tau. 2008;40(2):116–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00215.x. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke S, Salihu HM, Alio AP, Mbah AK, Jeffers D, Berry EL, Mishkit VR. Risk factors for major antenatal depression among low-income african american women. Journal of Women's Health (2002) 2009;18(11):1841–1846. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1261. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1261; 10.1089/jwh.2008.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malabarey OT, Balayla J, Klam SL, Shrim A, Abenhaim HA. Pregnancies in young adolescent mothers: A population-based study on 37 million births. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2012;25(2):98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.004. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness TM, Medrano B, Hodges A. Update on adolescent motherhood and postpartum depression. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 2013;51(2):15–18. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20130109-02. doi:10.3928/02793695-20130109-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead G, Morley W, Campbell P, Greig C, McMurdo M, Lawlor D. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;3:CD004366. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville JL, Gavin A, Guo Y, Fan MY, Katon WJ. Depressive disorders during pregnancy: Prevalence and risk factors in a large urban sample. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;116(5):1064–1070. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f60b0a. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f60b0a; 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f60b0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan S, Kershaw TS, Lewis J, Westdahl C, Rising SS, Patrikios M, Ickovics JR. Caregiving history and prenatal depressive symptoms in low-income adolescent and young adult women: Moderating and mediating effects. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31(3):241–251. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00367.x. [Google Scholar]

- Mollborn S, Morningstar E. Investigating the relationship between teenage childbearing and psychological distress using longitudinal evidence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50(3):310–326. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran S, Nagarathna R, Narendran V, Gunasheela S, Nagendra HR. Efficacy of yoga on pregnancy outcome. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (New York, N.Y.) 2005;11(2):237–244. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.237. doi:10.1089/acm.2005.11.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The etiology of gender differences in depression. In: Keita GP, editor. Understanding depression in women: Applying empirical research to practice and policy. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC US: 2006. pp. 9–43. doi:10.1037/11434-001. [Google Scholar]

- Panzarine S, Slater E, Sharps P. Coping, social support, and depressive symptoms in adolescent mothers. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 1995;17(2):113–119. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00064-Y. doi:1054-139X(95)00064-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Lopez F, Perez-Roncero G, Lopez-Baena M. Current problems and controversies related to pregnant adolescents. Revista Ecuatoriana De Ginecolagia y Obstetricia. 2010;17(2):185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Rimer J, Dwan K, Lawlor DA, Greig CA, McMurdo M, Morley W, Mead GE. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) 2012;7:CD004366. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub5. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva C, Ierardi E, Gazzotti S, Albizzati A. Motherhood in adolescent mothers: Maternal attachment, mother–infant styles of interaction and emotion regulation at three months. Infant Behavior and Development. 2014;37(1):44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.12.011. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Pousada D, Arroyo D, Hidalgo L, Perez-Lopez FR, Chedraui P. Depressive symptoms and resilience among pregnant adolescents: A case-control study. Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2010;2010:952493. doi: 10.1155/2010/952493. doi:10.1155/2010/952493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advanced Nursing Science. 1986;8(3):27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton MB, Flynn HA, Lancaster C, Marcus SM, McDonough SC, Volling BL, Vazquez DM. Predictors of recovery from prenatal depressive symptoms from pregnancy through postpartum. Journal of Women's Health (2002) 2012;21(1):43–49. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2266. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RS, Brandon AR. Adolescents, pregnancy, and mental health. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27(3):138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.09.008. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1016/j.jpag.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence: What changes, and why? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1021:51–58. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.005. doi:10.1196/annals.1308.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson W, Maton KI, Teti DM. Social support, relationship quality, and well-being among pregnant adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22(1):109–121. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0204. doi:S0140-1971(98)90204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Grindstaff CF, Phillips N. Social support and outcome in teenage pregnancy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1990;31(1):43–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warden D, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Kurian B, Zisook S, Kornstein SG, Rush AJ. Early adverse events and attrition in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment: A suicide assessment methodology study report. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;30(3):259–266. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181dbfd04. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181dbfd04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt WP, Wisk LE, Cheng ER, Hampton JM, Hagen EW. Preconception mental health predicts pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes: A national population-based study. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011:1525–41. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0916-4. doi:10.1007/s10995-011-0916-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, Oberlander TF, Dell DL, Stotland N, Lockwood C. The management of depression during pregnancy: A report from the american psychiatric association and the american college of obstetricians and gynecologists. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;114(3):703–713. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ba0632. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ba0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah R. Social support, life stress, and anxiety as predictors of pregnancy complications in low-income women. Research in Nursing & Health. 2009;32(4):391–404. doi: 10.1002/nur.20335. doi:10.1002/nur.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]