Abstract

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is an anion channel composed of 1480 amino acids. The major mutation responsible for cystic fibrosis results in loss of amino acid residue, F508, (F508del). Loss of F508 in CFTR alters the folding pathway resulting in endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation (ERAD). This study investigates the role of synonymous codon in the expression of CFTR and CFTR F508del in human HEK293 cells. DNA encoding the open reading frame (ORF) for CFTR containing synonymous codon replacements, were expressed using a heterologous vector integrated into the genome. The results indicate that the codon usage greatly affects the expression of CFTR. While the promoter strength driving expression of the ORFs was largely unchanged and the mRNA half-lives were unchanged, the steady state levels of the mRNA varied by as much as 30 fold. Experiments support that this apparent inconsistency is attributed to exon junction complex independent nonsense mediated decay. The ratio of CFTR/mRNA indicates that mRNA containing native codons was more efficient in expressing mature CFTR as compared to mRNA containing synonymous high expression codons. However, when F508del CFTR was expressed after codon optimization, a greater percentage of the protein escaped ERAD resulting in considerable levels of mature F508del CFTR on the plasma membrane, which showed channel activity. These results indicate that for CFTR, codon usage has an effect on mRNA levels, protein expression and likely, for F508del CFTR, chaperone assisted folding pathway.

Keywords: CFTR, Nonsense mediated decay, synonymous codon usage, CFTR F508del, Protein folding

Introduction

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is a membrane bound protein composed of 1480 amino acids with a mass of 168,142 Da and 180,000 Da after glycosylation. CFTR is a member of the ATP-binding cassette super-family 1. CFTR is also a member of the MRP (multidrug related protein) group, which is structurally related to the multidrug resistance family of proteins. The structure of CFTR has been modeled based, in part, on the structure of Sav18662. There are two membrane spanning domains (MSD1 and MSD2) each comprised of 6 transmembrane helices (TMH1-12). MSD1 spans from residues 66–376 while MSD2 spans residues 861–1166. MSD1 and MSD2 are thought to form an anion channel for chloride and bicarbonate, which acts to maintain normal ion balance in tissues 3. There are 2 nucleotide-binding domains, NBD1 and NBD2. NBD1 is formed by residues 377–637, while NBD2 consists of residues 1175–1430. NBD1 and NBD2 are thought to act as a heterodimer necessary for the regulation and formation of the chloride channel. There is also a regulatory domain (R), which is comprised of residues 674–847. The R-domain serves as a site of phosphorylation by protein kinase A or protein kinase C and is regulated by cAMP 4; 5. Thus, CFTR functions as a cAMP-regulated anion channel 6, located on the apical plasma membrane, where it regulates secretions in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.

Mutations in CFTR are responsible for cystic fibrosis (CF), the most frequent lethal genetic childhood disease. The mutation, c.1521_1523delCTT, effectively deletes the codon for F508 (F508del) and creates a synonymous codon replacement at Ile507 (c.1521C>T) 4; 7. This mutation is the most common and 90% of all patients with CF are either heterozygous or homozygous for this mutation. While there are reports that this synonymous codon replacement contributes to the disease state 8; 9, most studies on the effect of F508del have concentrated on the folding and expression of CFTR due to the deletion of F508 (for review, see 10).

The F508del mutation alters the folding and stability of CFTR and as a result, CFTR is ubiquitinated and degraded by ERAD (for review, see 11). Core glycosylation of wild type CFTR occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and full glycosylation occurs in the Golgi. For F508del CFTR, the steady state level of the core glycosylated is not greatly reduced in the cell, but there is little to no steady state level of the fully glycosylated form on the plasma membrane. Residue F508 is located in NBD1 domain and while F508del mutation does not alter the structure of the isolated domain 12; 13, it does appear to alter the conformation of the intact CFTR and reduce its stability. This effect can be explained in part by the current structural model of CFTR, which has NBD1 interacting with NBD2 and one or more cytosolic loops. The folding of F508del CFTR is proposed to be impaired and follow a pathway different from the normal protein, which leads it into a kinetic trap14. Second site suppressors have been identified in NBD1 and in other regions of CFTR, which partly overcome the defect and result in CFTR trafficking to the plasma membrane where it can function as a chloride channel, albeit with lower activity 15; 16; 17; 18. CFTR starts to fold co-translationally and folding is final after translation is completed 19; 20. The folding of CFTR occurs in a cooperative manner 21; 22, which is augmented and assisted by a number of chaperones, most notably, Hsc/Hsp 70 and Hsp90. Many interactions have been identified between CFTR and partner proteins and these are altered with F508del CFTR 23.

Many eukaryotic proteins start folding co-translationally 24; 25; 26; 27; 28. While eukaryotic translation systems are able to fold the multi-domain proteins efficiently, this is not observed using a bacterial protein synthesis extract 29. It was suggested that the reason for this difference was that the rate of protein synthesis may have affected the folding of the domains 29. These type of results have prompted speculation that the rate of translation might affect the folding of proteins. This speculation was fueled by the discovery that a single synonymous single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) apparently altered the folding of multi-drug resistance protein, MDR1, which was postulated to change the substrate specificity 30. The mutation C3435T, was shown to alter substrate specificity of MDR1 as well sensitivity to trypsin digestion, suggesting that the diseased MDR1 protein is in a different conformation 30. Similarly, mutations in MRP6 are responsible for the disease, pseudoxanthoma, but up to 40% of the mutations may also be due to synonymous SNPs that alter the folding of the protein 31. Thus, one hypothesis is that the synonymous codon altered the rate of translation thereby altering the folding of the protein (for review, see 32). More recently, codon usage has been shown to affect the expression, structure, and function of the circadian clock protein, FRQ, in Neurospora crassa 33.

Codon optimization is commonly used to increase expression levels of protein expressed using heterologous systems (see for review see 34). The rationale typically involves the presence of rarely used codons, which cause termination of translation rather than a direct relationship with protein folding. However, while codon optimization can result in higher expression, this does not always happen and can even result in lower expression of the protein.

Nonsense mediated decay (NMD) is a system in eukaryotic cells that is used to degrade mRNA that contains one or more nonsense mutations (for review, see 35; 36; 37; 38). NMD is thought to be a quality control system that prevents the wasteful production of truncated proteins. The standard mechanism depends on the association of a complex of proteins at the exon junction – referred to as the exon junction complex (EJC). The ribosome during the pioneering round of translation strips the EJC from the mRNA. In the absence of this, the EJC recruits other factors, including an endonuclease, which degrades the mRNA. There is a second method, sometimes referred to as “failsafe”, which is an EJC independent pathway but includes some of the same factors as in the EJC enhanced mechanism.

The results of the studies presented here suggest that non-optimal codon usage can result in NMD of the corresponding mRNA. This is likely due to the slowing of the rate of translation mimicking the effect of a nonsense codon. Further, we find that codon usage can alter the expression of a protein, in this case, F508del CFTR, as evidenced by expression level, the maturation, and the trafficking to the plasma membrane. The results suggest that codon usage can alter the rate of translation and alter expression in a number of different ways.

Results

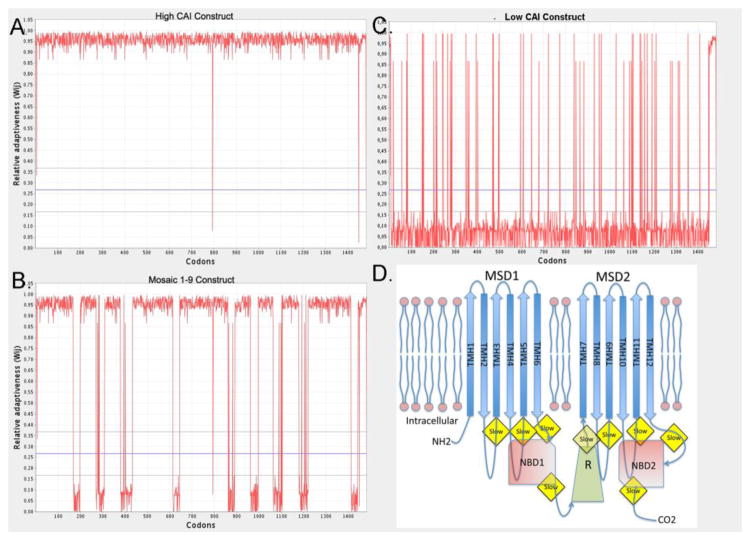

The impetus of this study was to determine if codon usage alters the expression of CFTR and to determine if there is relationship between codon usage and folding of CFTR. To answer these questions, a number of constructs were made with defined codons in the open reading frame (ORF) (Fig. 1, Supplement Figure 1S). The control construct contained the native codons derived from a cDNA clone encoding human CFTR (GenBank, M28668.1). There were 3 test constructs made synthetically: 1. one in which the codons were nearly entirely derived using codons with high codon adaptation index 39 (CAI) values (from www.jcat.de) and named hCAI. 2. one in which the codons were nearly entirely derived using codons with low CAI values, lCAI. 3. one in which there was a mosaic of codons containing values of high CAI and low CAI (mCAI). For the mCAI construct, the codons were almost all those with a high CAI value with the exception of 9 regions that followed regions encoding domains (cf. Fig. 1D, Supplement Figure 1S). From 30–54 codons with low CAI values were placed immediately after the codons encoding transmembrane helices (TMH) 1 and 2, 3 and 4, 5 and 6 (in MSD1), 7 and 8, 9 and 10, 11 and 12, (in MSD2) and after NBD1, NBD2, and the R-domain. The hypothesis was that the regions containing codons with low CAI values would slow translation and allow a longer time for the folding of these domains. For the regions after the TMH pairs, the low CAI codons were positioned about 30 codons downsteam of the codons encoding the last TMH. 30 amino acids correspond to the length (100Å which is equivalent to 30 amino acids in the extended conformation) of the bacterial ribosome exit tunnel40; 41. For NBD1, NBD2 and the R-domain, the low CAI codons were placed at or near the end of the domain, which allowed extended folding time before the completion of the synthesis of the domain. The first 7 codons were identical for all constructs, using native codons and also having a single silent replacement, c.18G>C, which created a unique XhoI restriction site. This uniformity at the 5′ end of the ORF minimized the affect of codons usage on translational initiation. The 5′ upstream non-translated region consisted of 52 nucleotides from human CFTR mRNA preceded by an engineered NheI site, which was used to clone into the expression vector, pcDNA5/FRT (Invitrogen). The final 33 codons were identical for the test constructs, all containing codons with high CAI values. A unique HindIII site used for cloning, followed these 33 codons. The 3′ noncoding end consists of 40 bases from non-coding region of human CFTR mRNA, followed in order by an EcoRV site, a KpnI site, 89 bases from the HIV GAG protein (1240–1328) followed by another KpnI site, and a PmeI site. The HIV GAG sequence served as a region used for priming DNA synthesis for real time PCR (rtPCR) analysis of mRNA levels. The expression vector has a human cytomegalovirus immediate early transcriptional promoter and a bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal sequence. The constructs were cloned into the NheI-PmeI sites of pcDNA5/FRT and transformed into HEK293 (Flip-In-293) cells. The clones were also modified to delete codon F508, to assess the effect of codon usage on the folding of this mutant protein. All constructs were entirely sequenced to ensure fidelity.

Figure 1. CFTR Codon Usage and Molecular Model.

The CAI index is plotted versus the residue number for codon optimized (hCAI) form of CFTR (A), the lCAI form (B), and the mCAI form (C). D. A model of CFTR showing the structural domains and the regions in mCAI where the clusters of codons with low CAI values are placed in the coding frame.

Steady State Levels of CFTR

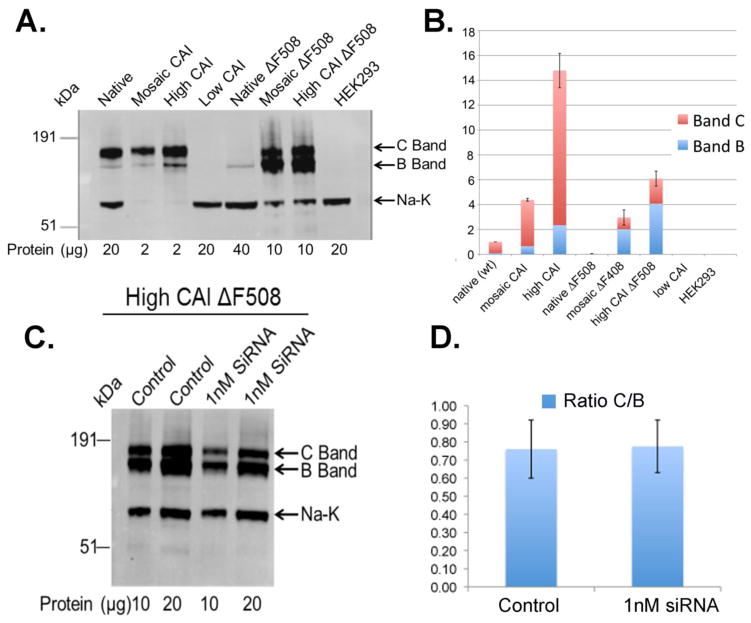

Fig. 2 shows the analysis of the steady state level of CFTR expressed in HEK293 cells with genes using codons from native gene, mCAI, hCAI, and lCAI and the corresponding genes with the F508del mutation. Evident from the Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A), the codon usage had a dramatic effect on the expression of both wild type and F508del CFTR. The core glycosylated form is represented in Band-B, while the mature complex glycosylated form is represented in Band-C. The level of the Na-K ATPase served as a control for extraction of membrane proteins and protein loading. For expression of wild type CFTR using the native codons, the expression level was typical with a corresponding Band-C to Band-B ratio (C/B) of about 11 Also typical, expression of F508del CFTR using native codons was dramatically lowered (25 fold) and only the core glycosylated form in Band-B was detected. Expression of both wild type and F508del CFTR using either mCAI or hCAI was dramatically higher. For wild type CFTR, mCAI and hCAI resulted in about 4 fold and 15 fold greater expression as compared to native codons. In both cases, the C/B ratios were comparable to expression using the native codons differing by a factor of about 2. Dramatically, when comparing the sum of the levels of Band-B and –C, the level of F508del CFTR with expression using hCAI was 150 fold higher, and 75 fold higher with mCAI, as compared to when expressed using native codons. Furthermore, expression of F508del CFTR with mCAI or hCAI was even higher than expression of wild type CFTR using native codons (3 fold and 6 fold, respectively). Even when considering just the level of the mature glycosylated form of F508del CFTR, the mCAI had comparable levels and hCAI had about twice the level as compared to wild type CFTR expressed using native codons. Clearly however, the C/B ratio was dramatically different for the expression using F508del CFTR in either mCAI or hCAI (0.7) as compared to expression of wild type CFTR (11). Thus these results indicate a dramatic effect of codon usage on the expression of F508del CFTR suggesting that translation had been altered to allow F508del CFTR to escape ERAD.

Figure 2. Dependence of expression of wild type CFTR and F508del CFTR on codon usage.

A. Western blot analysis of total protein extracted from HEK293 cells using a monoclonal antibody directed against CFTR (593 from Univ. North Carolina). An antibody directed against the Na-K ATPase was used as an internal control. B. Quantification of the Western blot data. The data were quantified by measuring the intensity of the fluorescence of the secondary antibody using an Odyssey detector (Licor). Notice that the amount of total extracted protein varied per lane to allow analysis. Band B (blue) represents the core glycosylated form of CFTR, which is present in the ER. Band C (red) represents the complex glycosylated form of CFTR, which is present in the Golgi and plasma membrane. C. The expression of CFTR F508del was reduced by the addition of siRNA that targeted the 3′ nontranslated region of CFTR F508del mRNA. The left image is a Western blot analysis of the CFTR F508del from protein expressed in HEK293 cells in the presence and absence of 1nM siRNA. The siRNA reduced the expression of CFTR F508 del by about 45% but had no effect on the C:B ratio as shown in the bar graph (D.).

Analysis of the levels and expression of the mRNA

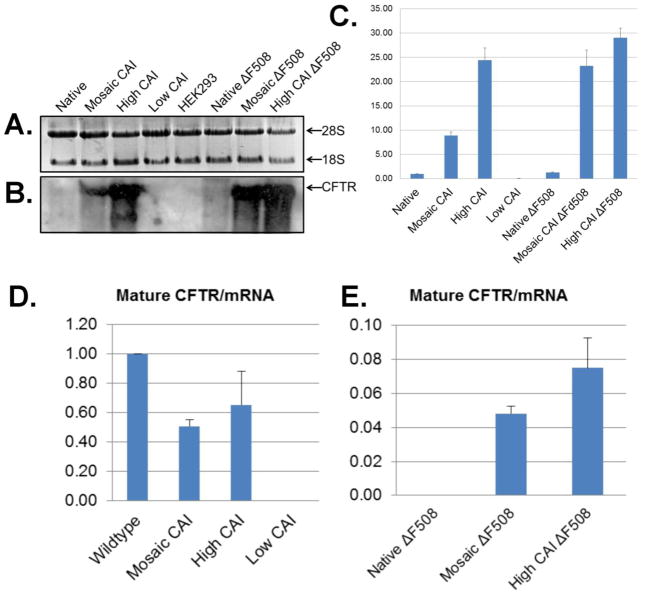

Before investigating more into the trafficking and function of CFTR and F508del CFTR, the levels and expression of the CFTR encoding mRNA for each construct were assessed. Steady state levels of the corresponding mRNAs were measured by Northern Blot analysis (Fig. 3A, B) and real time PCR (Fig. 3C). Surprisingly, the analysis indicated that the codon usage had as much as a 30-fold effect on the level of the mRNA. Further, the level of mRNA correlated with the level of CFTR as measured by Western Blot analysis as the amount of CFTR increased with the amount of mRNA. There was a very low level of mRNA, detectable by real time PCR, for CFTR from expression of the gene using low CAI codons. Analysis of the ratio of the relative amount of mature CFTR/mRNA, indicates CFTR expressed from the native codons is about 2 fold more efficient at producing mature CFTR than with expression from using either the high CAI or mosaic CAI codons (Fig. 3D, E). However, for F508del CFTR, the relative efficiency of mature CFTR/mRNA when expressed using hCAI codons was almost 8% as compared to that of wild type CFTR expressed using the native codons. When considering total expression (Band-B plus Band-C) the relative efficiency of total CFTR/mRNA when expressed using hCAI codons was almost 20% as compared to that of wild type CFTR expressed using the native codons. While this efficiency may appear to be low in comparison to the expression of the wild type CFTR, it is dramatically high in comparison to expression of F508del CFTR using native codons.

Figure 3. Effect of codon usage on steady state levels of mRNA.

A. Fluorescence image of total cellular RNA after separation by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. Only the region showing the 28S and 18S rRNA is shown. B. Northern blot analysis using a radiolabeled oligonucleotide probe directed against the 3′ non-translated region of the mRNAs. C. Quantitative analysis of the data from B. D/E. Relative ratio of Band C/mRNA derived from data in B. and C. Note the differences in the scales.

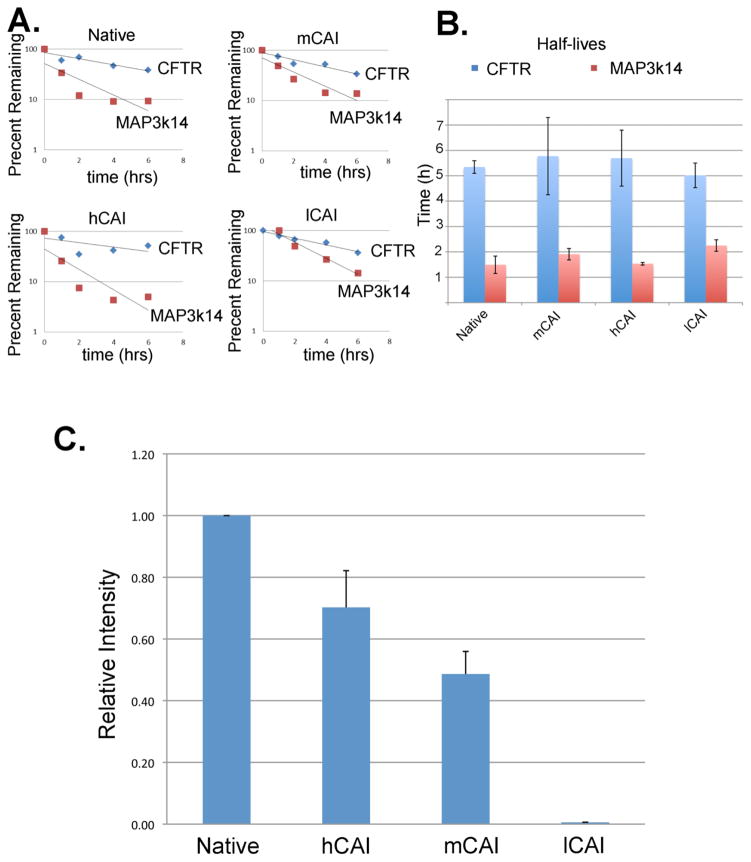

The effect of codon usage on the steady state of mRNA level was surprising and thus we examined the cause of this effect. The steady state level of mRNA is a function of the rates of synthesis and degradation. The rate of degradation of the mRNA was measured by determining the cellular half-life of the corresponding mRNA after inhibition of transcription using actinomycin D (2μM). As a control, we measured the half-life of mRNA for MAP3k14 with a reported valued of about 1.2 hrs in HeLa cells 42. The results shown in Fig. 4A,B indicate that the half-life for MAP3k14 mRNA is about 1.5 hrs while the half-life of the mRNA for CFTR was about 4–5 hours, independent of the codons used in the CFTR ORF. Thus, this indicates that differences in half-lives amongst the CFTR mRNAs was not responsible for the differing levels of CFTR mRNA.

Figure 4. Analysis of the stability of the mRNA and relative promoter strength of the constructs.

A. The cellular levels of the mRNA corresponding to CFTR and MAP3k14 were measured in HEK293 cells after addition of actinomycin D (2μM) and the results plotted in B. C. Nuclear run-on analysis to measure the relative promoter strength of the constructs using native codons, hCAI, mCAI, and lCAI. The amount of CFTR mRNA measured relative to the level of GAPDH mRNA, as described in Material and Methods.

The promoter strength was measured to determine if the promoter strength was altered thereby altering the rates of transcription of the genes. Fig. 4C shows that with the exception of lCAI, the promoter strength, as measured by nuclear run-on analysis, did not differ by more than a factor of 2 and thus, also could not account for the large changes observed in the level of the mRNA. Expression of CFTR using lCAI codons nearly eliminated transcriptional activity suggesting that there were cis acting elements that inhibited RNA polymerase II binding. However, for expression using native codons, mCAI and hCAI, while there were dramatic changes in the steady state levels of the mRNA, this could not be explained by either the half-life of the mRNA or by the rates of transcription as assessed by promoter strength.

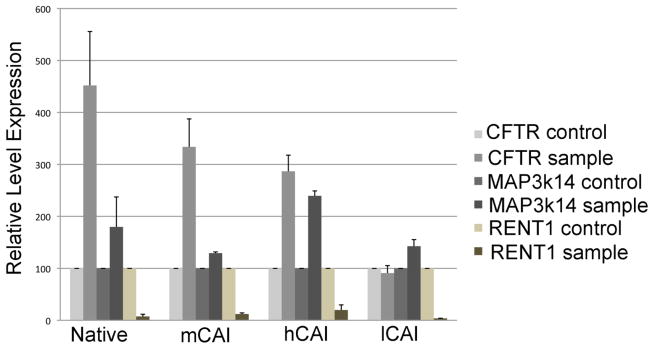

One possible explanation to resolve this apparent paradox is that exon-junction complex (EJC) independent non-sense mediated decay (NMD) was responsible for the degradation of the mRNA 43; 44; 45; 46; 47; 48; 49; 50; 51; 52 and that the degree of NMD differed depending on the codon usage in the CFTR ORF. NMD occurs before the pioneering round of translation and thus the mRNA destined for NMD does not contribute to the analysis of the half-life of the steady state mRNA and is not differentiated in nuclear run-on experiments. To test this hypothesis, siRNA was used to reduce the level of RENT1 (UPF1) in the cell and then the level of CFTR mRNA was measured after 48 hrs. RENT1 is an essential component of both exon junction complex enhanced and independent NMD 43. As an internal standard, the level of GAPDH mRNA, which is not subject to NMD 42, was measured. As a control, the level of MAP3k14 mRNA was measured because MAP3k14 is known to be under the control of NMD 42; 53; 54. The prediction was that by inhibiting NMD, the relative amount of cellular CFTR mRNA would increase if NMD was active on CFTR mRNA. Also, the expectation was that NMD would be greater for CFTR using native codons and less for CFTR using codons containing high CAI values. Fig. 5 shows that the level of MAP3k14 mRNA increased from about 1.5 to 2.4 fold with the decrease in expression of RENT1, which presumably decreased NMD. Strikingly, the levels of CFTR mRNA were increased after reducing the levels of RENT1. Increase in the levels of mRNA occurred for the transcripts containing native codons in the ORF, as well as the expression from the genes using codon, mCAI and hCAI. Dramatically, CFTR mRNA increased about 4.5 fold using the native codons, to 3 fold for mCAI and 2.3 fold for hCAI. This trend corresponds with the steady state levels of mRNA observed for the native, mCAI, and hCAI codons. The lower level of mRNA from expression of CFTR using native codons could be explained, in large part, by the greater amount of NMD relative to the mRNA from mCAI and hCAI. Thus, this data supports the hypothesis that NMD was responsible for the differences in the level of the mRNA for CFTR.

Figure 5. CFTR mRNA is modulated by nonsense mediated decay.

The cellular levels of mRNA were measured in HEK293 cells 48h after addition of siRNA against RENT1. The mRNA levels are relative to the levels of GAPDH mRNA and normalized relative to the levels of cellular levels of mRNA after addition a scrambled siRNA. The levels of MAP3k14 served as a control for a mRNA that is known to be under regulation by NMD.

Cell Surface Localization of F508del CFTR

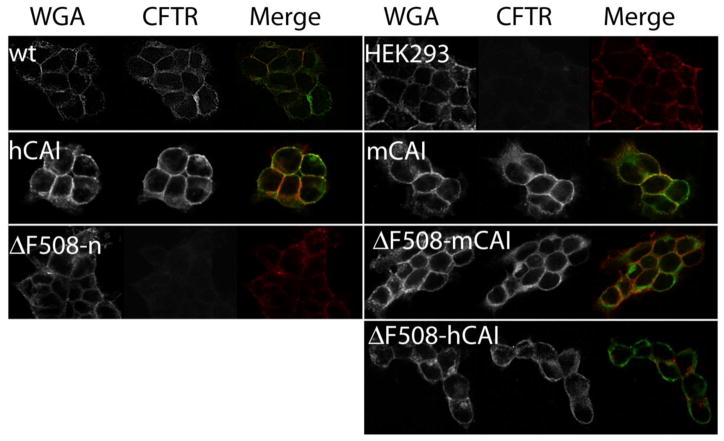

The large amount of complex glycosylated CFTR (Bands-C) from cells expressing F508del CFTR using hCAI codons suggested that F508del CFTR escaped ERAD and was successfully trafficked to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2). To investigate this hypothesis, immunofluorescent imaging studies were performed on cells expressing CFTR using antibodies directed against CFTR and wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with Rhodamine, which is a fluorescent marker for the plasma membrane. Fig. 6 shows that not only was F508del CFTR located on the plasma membrane, but the relative signal correlated with the amount of CFTR in the cell as determined by Western blot analysis of the detergent (1% NP-40) soluble cellular protein (cf. Fig. 2). Next, it was tested if ERAD system was being overwhelmed by the high expression of F508del CFTR thus allowing greater escape from ERAD. If ERAD was being overwhelmed by the high expression of F508del CFTR, then it would be predicted that by reducing the expression of F508del CFTR that the ratio of Band-C relative to Band-B would decrease. Thus, siRNA directed against the 3′ end of the F508del CFTR mRNA (hCAI) was added to the cells and after 48 hrs the protein was extracted and tested by Western blot analysis using antibodies against CFTR (Fig. 2C,D). The C/B ratio was constant at 0.7, despite about a 45% decrease in the amount of F508del CFTR. Thus, this result supports the conclusion that F508del CFTR was not escaping ERAD by overwhelming the system.

Figure 6. Immunofluorescence Images of HEK293 Cells Expressing Wild Type and F508del CFTR.

The images show the staining with wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with Rhodamine (red), (which stains the plasma membrane), mAb directed against CFTR followed by a secondary antibody labeled with Alexa-488 (green), and the merged images with co-localization in yellow.

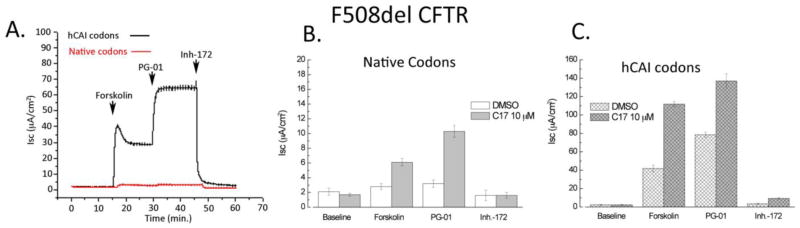

We next assessed if F508del CFTR expressed using native or hCAI codons possessed channel activity (Fig. 7). Constructs were expressed stably in Fischer rat thyroid cells (FRT), which make no endogenous CFTR. Cells were grown at 37°C as monolayers on permeable supports, placed in a modified Ussing chamber to measure CFTR mediated chloride currents. Cells were exposed to a CFTR corrector, C17, which acts to increase the amount of F508del CFTR trafficked to the cell surface, and a potentiator, PG-01, which acts to increase channel activity of CFTR on the plasma membrane. In FTR cells expressing native CAI F508del CFTR, forskolin and PG-01, elicited minimal response consistent with little F508del CFTR on the plasma membrane. In contrast, FRT cells expressing hCAI F508del CFTR, forskolin elicited a robust chloride secretory response. Peak secretion was ~40 μA/cm2, which fell to a steady state level of ~30 μA/cm2. The current was potentiated by addition of PG-01 to a new steady state level of ~70 μA/cm2, which was greatly reduced by the CFTR inhibitor, inh-172. Thus, the currents generated by hCAI F508del CFTR in cells grown at 37°C is fully attributable to F508del CFTR. While FRT cells are not identical to HEK293 cells, codon usage in human and rat is similar (Table 2S), and thus is expected to show the same effects on expression using clones based on human codon usage. These results indicate that the codon usage has allowed a considerable amount of F508del CFTR to escape ERAD and traffic to the plasma membrane where it is functional.

Figure 7. Short circuit current (Isc) measured in native and hCAI F508del CFTR expressing FRT cells.

A. Typical trace of current measurements for F508del CFTR. B. Current measurements for F508del CFTR expressed using native codons. C. Current measurements for F508del CFTR expressed using hCAI codons. Transfected cells were treated overnight with 10 μM C17 (a chemical corrector) or an equivalent amount of DMSO. For chemical correcting, C17 was added to the cells and the cells were incubated for 24 hrs before measuring conductance. Isc was measured before (baseline) and after the sequential addition of Forskolin (10 μM), PG-01 (10 μM) and Inh-172 (20 μM). Values are the means +/− SEM for n=6 filters. Note the axis scale.

Discussion

There are two striking conclusions from this study. First, codon usage in CFTR ORF affected the level of CFTR mRNA and this could be attributed to nonsense mediated decay. The transcription of CFTR from the construct contained low CAI codons (lCAI) was keenly depressed, and while this was not investigated, it is assumed that some part of the sequence had acted in cis to inhibit transcription. However, for the native, mCAI and hCAI constructs, NMD appeared to be active and most active for CFTR containing the native codons. It should be noted that the ORFs do not contain any introns. Thus exon junction complex enhanced NMD is not likely operable and it must be acting via the exon junction complex independent NMD. NMD is normally elicited when a ribosome is stalled at a nonsense codon, which either recruits factors in the NMD pathway, including RENT1 (UPF1), or cannot clear the preassembled NMD complex in the pioneering round of translation 37; 38; 43; 44; 49. As such, there is race between the ribosome completing translation and NMD. There are likely 2 factors that are impacting NMD in this study. First, CFTR mRNA is long – about 5000 bases including non-coding regions in these constructs. A feature for NMD is the presence of a long 3′ nontranslated region that is far from the translational termination site 43; 51; 55; 56; 57; 58. This feature is seemingly fulfilled notwithstanding the absence of a nonsense codon. In NMD, the nonsense codon causes the ribosome to pause, which is the triggering event for NMD. We are proposing that a cluster of codons that have a low CAI value can also cause pausing of the ribosome along the mRNA mimicking the effect of a nonsense codon. Furthermore, there is an additive effect for each cluster of poor codons that the ribosome encounters. Thus, NMD will be greater with increasing number of clusters of codons with low CAI values and with the increasing length of the mRNA. Based on the observed CAI average value, the codons usage used natively in human mRNA is not optimal. The overall CAI value for the human coding region for the CFTR mRNA is 0.158 where the optimized gene has an overall value of 0.967. As expected from this low CAI valued, the sequence frequently has long stretches of regions of codons with low CAI values. The expectation is that the ribosome has the potential to stall at many positions along CFTR mRNA mimicking the effect of a nonsense codon and thereby causing NMD. If correct, this would predict that NMD would be less for the codon optimized sequence (hCAI); this is exactly what is observed as indicated by the steady state level of mRNA and the effect of knocking down the expression of RENT1 (cf. Fig. 3 and 5).

While the codon usage for native CFTR mRNA is not optimized, as judged by the average CAI index, the efficiency as determined by cellular level of CFTR/mRNA is about 2 fold higher than when the codons were optimized based on CAI values (hCAI) (Fig. 3). This indicates that improving the codon usage based on CAI values, did not improve the efficiency of translation of the wild type CFTR mRNA or the subsequent folding of CFTR. This also held true for CFTR mRNA that was comprised of codons with a mosaic of codons with high and low CAI values. The mCAI construct was designed to test the premise that folding of the domains in CFTR would benefit from slowing the rate of translation at the end of the domain. But, this proved not to be correct for the folding of wild type CFTR. This hypothesis was based in part by the demonstration that the domains of CFTR folded independently, but also with interdependence and in a cooperative manner 15; 21; 22; 59; 60. The results here suggest that the rate of folding of the domains in CFTR is fast enough as not to be constrained by the rate of translational elongation even when the codons are optimized based upon CAI values.

The second striking result from this study was that when codons were optimized based on CAI values (high CAI), that there was a dramatic effect on the ability of F508del CFTR to escape ERAD and successfully traffic to the plasma membrane and function as an anion channel. This was opposite than what was predicted because the F508del mutation is thought to impair folding of CFTR 2; 12; 13; 21; 22; 61; 62; 63; 64; 65; 66. Increasing the rate of translation would allow less time to fold the domains before completion of translation and thus the amount of F508del CFTR would be predicted to be lower in the hCAI construct as compared to the mCAI or the native codons 67; 68; 69; 70. Thus, the obvious question is how did changing codon usage allow F508del CFTR to escape ERAD?

Mass action may be a contributing factor responsible for the increase of F508del CFTR on the plasma membrane. However, while mass action may be a contributing factor, we do not believe that it is the primary cause. The level of F508del CFTR expressed using the native codons shows no mature glycosylated form (Band C) (Fig. 2). If mass action was a primary force in the expression of F508del CFTR using hCAI codons, then the Band C and B ratio for F508del CFTR expressed using native codons would be 0.7, as that for F508del CFTR expressed with hCAI codons (Fig. 2B,D). This is clearly not the case as no Band C is visible for F508del expressed using native codons and this is consistent with other studies71. While there is a small amount of Forskolin activated channel activity (Fig. 7) with FRT cells expressing F508del CFTR with native codons, this activity is likely due to the corrector activity of DMSO72, which was added to the cells as a vehicle control. Thus, we believe there is a second more significant reason for F508del CFTR escaping ERAD and getting to the plasma membrane.

The folding of CFTR starts co-translationally but continues even after completion of translation (for review, see 11). The maturation includes post-translational glycosylation, which starts with the core glycosylation in the endoplasmic reticulum and is completed with complex glycosylation in the Golgi. The folding of CFTR is assisted by a large number of chaperones, with major contributions by heat shock proteins, Hsp70 and Hsp90 complex, Dnaj homologs, Hsp40 and Hdj-1/2, and calnexin 65; 73; 74; 75; 76; 77. In contrast, F508del CFTR has a defect in the kinetics of folding and the final folded product is less stable as compared to wild type CFTR 63; 78; 79; 80. F508del CFTR is degraded via an Hsc70 dependent ubiquitination pathway, which occurs in the ER and effectively prevents trafficking to the Golgi 81; 82; 83. As such, very little F508del CFTR makes it to the plasma membrane.

There are a number of reports on rescuing F508del from ERAD including growing the cells at low temperature 84; 85, by using chemical “correctors” 86; 87; 88, with second site suppressors 15; 16; 17; 18, by the addition of chemical chaperones 89; 90; 91; 92, and by modulation of the expression of chaperones and co-chaperones 23; 93; 94; 95; 96; 97. Rescue can occur by stabilizing F508del CFTR or assisting in the folding as to prevent it from entering into a kinetic trap 14; 23; 61; 63; 98. The rescue of F508del CFTR by expressing with different synonymous codons must act by a kinetic mechanism whereby the increased rate of translation alters the folding pathway and allows the mutant CFTR to escape detection by ERAD. The basic premise for both of these features is that the rate of translation either reduces or increases certain interactions leading to rescue of F508del CFTR. This can be illustrated by the binding cycle of Hsp90 Hsc/p70/Hdj1 for the folding and degradations of CFTR. Hsp70 with the co-chaperone Hsp40, binds co-translationally to hydrophobic stretches and promotes the folding of the client. However, if Hsp70 remains bound too long, then CFTR is ubiquitinated and targeted for degradation. Using an in vitro model, it was demonstrated that the timing of the Hsp/Hsc70 binding cycle plays a critical role in determining the fate of CFTR 99. Paradoxically, sodium 4-phenylbutyrate has been shown to rescue F508del CFTR and coincidently increase the expression of Hsp70 97. The binding cycle of Hsp90 seems to follow a similar story. Hsp90 is known to bind to proteins and promote folding (reviewed in 10; 100; 101; 102). Disruption of Hsp90 interactions with CFTR with the geldanamycin and herbimycin A decreased the maturation and increased degradation of CFTR in Chinese Hamster Ovary and Baby Hamster Kidney cells 75. The co-chaperone, Aha1 binds to Hsp90 and activates the ATPase activity of Hsp90, which in turn promotes the binding of Hsp90 to client proteins. Again, paradoxically, while Hsp90 binds to CFTR and aids in it’s folding and trafficking, lowering expression of Aha1 in HEK293 cells rescued F508del CFTR 23. It cannot be concluded with certainty in either of these cases that the changes Hsp90 or Hsp/Hsc70 were directly responsible for the rescue of F508del. However, the rescue likely involves altered interactions of F508del CFTR with chaperones that promote its folding or the proteins that target it for degradation.

By increasing the rate of translation by altering the codon usage, we suggest that the regions that are targets for chaperones are present for a shorter time and thus present at different levels as compared to the F508del CFTR expressed using the native codons. This may result in a widely different array of chaperones bound the protein and binding occurring at different times of the folding pathway. Possibly, for F508del CFTR, the more rapid appearance of NBD2 would allow for the more rapid cooperative interactions between NBD1 and NBD222 promoting a conformation that is more native like and not as quickly targeted for degradation by ERAD.

The results illustrate another way to rescue F508del CFTR and allow trafficking to the plasma membrane. The logical next step is to identify the differences in the number and types of chaperones bound to F508del CFTR when expressed in using native codons as compared to codons with high CAI values. These studies will provide a rational approach for targeting genes which when expression is modified, can be used to treat cystic fibrosis. In addition, it may be possible that if NMD is active on native CFTR mRNA, that current methods could be used to reduce NMD and increase the level of CFTR mRNA in the lung cells of patients with cystic fibrosis. Decreasing NMD of CFTR mRNA could be used in combination therapies to increase the amount of functional or partially functional CFTR on the plasma membrane.

Material and Methods

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

Flip-In HEK 293 (Invitrogen) (human embryonic kidney epithelial kidney) cells were used in the study. These cells contain a single integrated FRT site, located at a transcriptionally active region allowing targeted integration of gene. HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10%), penicillin/streptomycin (1%) and zeocin (100μg/ml), at 37°C. Fisher Rat Thyroid (FRT) cells were used to study CFTR channel activity and were maintained in Coon’s modified F12 medium supplemented with FBS (5%), L-glutamine (2mM), penicillin/streptomycin (1%).

Antibodies and Reagents

Mouse monoclonal, clone 596 anti-human CFTR antibody, was obtained from Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Inc. (Chapel Hill, NC). Other antibodies used were mouse anti Na, K-ATPase β-1 subunit (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa), Infrared Dye 800 linked secondary antibodies, goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and Alexa Fluor 488 dye conjugated to goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Rhodamine labeled wheat germ agglutinin was used for labeling plasma membrane (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA).

Plasmids and Transfections

Standard molecular biology methods were performed throughout103. Synthetic CFTR constructs with High Codon Adaptive Index (hCAI), Low CAI (lCAI), Mosaic of High and Low CAI (mCAI) were commercially made (Genscript, Piscataway, N.J.) and sequenced to ensure integrity. Native CFTR was obtained from the clone obtained from Dr. John Riordan (Univ. North Carolina). The synthetic and native constructs were subcloned in pcDNA5/FRT vector (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for stable transfection in Flip-In 293 cells. The CFTR constructs were mutated to generate CFTR-F508del mutation using QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA). Native F508del and hCAI F508del were subcloned in pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for transient transfection in FRT cells.

HEK293 cells (1x105) were plated per well in 6-well plates, following 24 h they were co-transfected with CFTR constructs and Flip-Recombinase Expression Vector, pOG44 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) with a ratio of 1:9 (w/w) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer’s instruction. Stable cell population was selected 48 h post transfection using hygromycin (150μg/ml). Fischer rat thyroid (FRT) cells were stably transfected with CFTR constructs sublconed into pcDNA3.1 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and OptiMEM media (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer’s instructions and selected with G418 (500μg/ml).

Immunoblot Analyses

Cells were harvested and lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 50mM Tris-Cl; pH 8.0, containing AEBSF-HCl, (1mM) aprotinin (0.8 μM), bestatin (5μM), E-64 (15μM), EDTA (0.5mM), leupeptin (20μM), pepstatin A (10μM) and the debris cleared by centrifugation at 1200g for 10 min at 4°C. Samples were prepared in 4x lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer, heated to 30°C for 5 min and resolved on 4–12% gradient Tris-glycine (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to polyvinyldiflouride (PVDF) membrane by electroporation as described except that the transfer buffer did not contain methanol 104. PVDF membrane was blocked in blocking buffer (5% milk prepared in PBS with 0.01% Tween-20) for 1 hour and incubated overnight with primary antibodies. InfraRedDye (IRDye) 800 or 680 conjugated to anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG were used as secondary antibodies. Fluorescence intensity was measured using Odyssey Infrared Image System.

RNA-mediated Interference

siRNA against CFTR gene, Rent 1 and scrambled siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon, Inc (Lafayette, CO). The working concentration was determined from the initial experiments optimizing the concentration for the minimum concentration of siRNA required to knockdown gene by more than 80% as calculated by mRNA levels. To knockdown expression of CFTR in hCAI F508del CFTR, cells were transfected with siRNA targeting human CFTR gene. To this end, the cells were plated in 6-well plates at 1x105 cells/well for 24 h and were transfected with siRNA against the target (1nM) or 1nM scrambled siRNA using Dharmafect reagent (Lafayette, CO). The transfection media was removed after 16 h and cells were cultured in complete media for 48 h, following which immunoblot was performed. To address if CFTR mRNA undergoes non-sense mediated decay (NMD), Flip-in 293 cells expressing CFTR constructs were transfected with either scrambled siRNA or siRNA against Rent 1 (1nM). Real time PCR was performed as mentioned below to measure relative increase in CFTR and MAP3K14 mRNA levels at 48h. Experiments were conducted at 48h after transfection as significant level of cell death was observed beyond that time.

RNA Isolation, Northern Blot

Expression of CFTR encoding mRNA was evaluated for each CFTR constructs using Northern Blot analysis105. Total cellular RNA was isolated from cells using Trizol RNA isolation reagent. The extracted RNA was dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate treated water. Equal amounts of RNA samples were denatured at 70°C for 15 min and resolved on a formaldehyde gel (1% agarose, 1% MOPS and 6.6% formaldehyde). Equal loading was verified based on staining of the 28S and 18S rRNA. RNA was hybridized at 42°C for 4h with 32P end labeled CFTR oligo (GAG reverse primer, the GAG region (89 bases 1240–1328) is from HIV GAG gene and inserted into the 3′ nontranslated end of the mRNA for all of the constructs. A final wash using 0.2X SSC-0.1% SDS for 10 min at 65°C, and the membrane was exposed to x-ray film for 24 h at −80°C.

RT-PCR and Quantitative Real Time PCR

Results from Northern blot were further verified with quantitative real time PCR (qPCR)106; 107. Complementary DNA synthesis reactions were performed with RNA (1μg) using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) according to manufacturer instruction. The expression of CFTR and GAPDH was determined using real-time PCR. cDNA samples were amplified using SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Detection System (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Briefly, cDNA (20ng) and gene specific primers (Primers are listed in Table 1S of the Supplement) were added to SYBR Green Master Mix and subjected to PCR amplification (1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 sec, 60 °C for 1 min), followed by a dissociation stage (1 cycle at 95 °C for 15 sec, 1 cycle at 60 °C for 1 min and 95 °C for 15 sec). All PCR reactions were run in triplicates. The amplified transcripts were quantified using the comparative ΔΔCt method106.

Analysis of mRNA stability

To estimate the stability of CFTR transcript, cells were incubated with either DMSO or actinomycin D (2μM) for 0, 2,4,6 and 8h to arrest de novo synthesis of RNA107. RNA was extracted, the amount of CFTR and MAP3k14 mRNA was quantified using real time PCR as described above (Primers listed in Table 1S of Supplement). The transcript for the housekeeping gene, GAPDH showed no difference in stability within the period of study.

In vitro Transcription Nuclear Run on Assay

Real Time PCR based nuclear run on assay was performed to analyze relative in situ transcription rate of CFTR constructs in intact nuclei 108. Cells in 10-cm dishes were rinsed with ice cold PBS and scraped in NP40 lysis buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl2, 0.5% NonidetP-40) with (AEBSF-HCl, (1mM) aprotinin (0.8 μM), bestatin (5μM), E-64 (15μM), EDTA (0.5mM), leupeptin (20μM), pepstatin A (10μM) on ice, followed by addition of the equal volume of 0.6 M sucrose buffer. Cell nuclei, obtained after centrifugation at 500g for 10 min, were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in transcription reaction buffer (20mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 200mM KCL, 200mM Sucrose, 5mM MgCl2, 4mM dNTPs, 4mM dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol). The RNA was purified and quantitative real time PCR was performed as described above. The negative control used isolated nuclei that were not incubated with reaction buffer.

Immunoflourescence

Immunoflourescence was performed to study localization and expression of CFTR constructs.. HEK293 cells (1x104) expressing CFTR constructs were plated onto poly-lysine-coated coverslips for 24 h. Cells were washed in PBS at room temperature and fixed in buffer (100mM PIPES pH 6.5, 1mM MgCl2, 1mM EGTA, 3.7% paraformaldehyde) for 5 min and buffer (100mM sodium borate pH 11.0, 1mM MgCl2) for 10 min. Cells were washed with sodium phosphate buffer saline (PBS), and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were washed with PBS 3 times and paraformaldehyde was quenched by incubation with 50mM NH4Cl for 15 min. Cells were blocked for 1 hour with PBS containing 10% goat serum, 1% BSA following which they were incubated in primary antibody against CFTR (mAb, 596). After washing, the cells were incubated with Alexa 488 conjugated anti mouse IgG antibody (Invitrogen) and the cells were counter stained with rhodamine labeled wheat germ agglutinin. Cells were mounted with Prolong Gold with DAPI medium (Invitrogen). Multiple coverslips were imaged (≥30 cells per coverslip) under identical settings and fluorescence intensity was determined using Image-J software.

Short-Circuit Current (Isc) Measurements

FRT cells seeded onto permeable tissue culture inserts (Transwell Clear; 0.44μM pore size, 6mm diameter; Corning) were maintained for 14 days without G418 antibiotic and current measurements were performed post 24 treatment with 10μM C17, a F508del-CFTR Corrector or DMSO for 24 hours. Current measurements were performed on epithelial cell monolayers in Ussing chamber; basolateral side of FRT epithelia consisted of Buffer A (120mM NaCl, 25mM NaHCO3, 3.3mM KH2PO4, 0.8mM K2HPO4, 1.2mM MgCl2, 1.2mM CaCl2, and 10mM glucose, pH7.4) 109. The bath solution for apical membrane was identical to Buffer A with exception of 120mM NaCl was replaced by 120mM Na-gluconate and 5.8mM CaSO4 in order to create a trans epithelial Cl− concentration gradient ([Cl−], 120mM). All solution were maintained at 37°C and aerated continuously with 95% O2, 5% CO2. The cells in the monolayer were continuously short circuited with a voltage clamp (University of Iowa City, IA), and trans-epithelial resistance was monitored by periodically applying a 2mV bipolar pulse, simultaneously calculating resistance from the current change. CFTR activity was measured by the change in Isc upon stimulation with forskolin (10μM), potentiator PG-01 (10μM), and CFTRInh-172 (10μM) was used to confirm CFTR dependence.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Changing the synonymous codons in the open reading frame of CFTR increases expression by 30 fold due to changes in RNA stability.

Nonsense medicated decay is active on CFTR mRNA and dependent on synonymous codon usage.

Altered codon usage can rescue CFTR F508del

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01GM066223 and R21HL094951 and a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, MUELLE08P0, to DMM and NIH grant 1R01HL102208 to NB.

Abbreviations

- CAI

codon adaptation index

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- ERAD

endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation

- EJC

exon-junction complex

- MDR

multi-drug resistance

- MSD

membrane spanning domains

- NMD

nonsense mediated decay

- ORF

open reading frame

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- TMH

transmembrane helix

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.CFTR_Gene_Family. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=gene&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=1080&ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Gene.Gene_ResultsPanel.Gene_RVDocSum.

- 2.Serohijos AW, Hegedus T, Aleksandrov AA, He L, Cui L, Dokholyan NV, Riordan JR. Phenylalanine-508 mediates a cytoplasmic-membrane domain contact in the CFTR 3D structure crucial to assembly and channel function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3256–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800254105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guggino WB, Stanton BA. New insights into cystic fibrosis: molecular switches that regulate CFTR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:426–36. doi: 10.1038/nrm1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–73. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt JF, Wang C, Ford RC. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (ABCC7) structure. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:a009514. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rommens JM, Dho S, Bear CE, Kartner N, Kennedy D, Riordan JR, Tsui LC, Foskett JK. cAMP-inducible chloride conductance in mouse fibroblast lines stably expressing the human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:7500–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zielenski J, Rozmahel R, Bozon D, Kerem B, Grzelczak Z, Riordan JR, Rommens J, Tsui LC. Genomic DNA sequence of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. Genomics. 1991;10:214–28. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartoszewski RA, Jablonsky M, Bartoszewska S, Stevenson L, Dai Q, Kappes J, Collawn JF, Bebok Z. A synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism in DeltaF508 CFTR alters the secondary structure of the mRNA and the expression of the mutant protein. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28741–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.154575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazrak A, Fu L, Bali V, Bartoszewski R, Rab A, Havasi V, Keiles S, Kappes J, Kumar R, Lefkowitz E, Sorscher EJ, Matalon S, Collawn JF, Bebok Z. The silent codon change I507-ATC->ATT contributes to the severity of the DeltaF508 CFTR channel dysfunction. Faseb J. 2013;27:4630–45. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-227330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chanoux RA, Rubenstein RC. Molecular Chaperones as Targets to Circumvent the CFTR Defect in Cystic Fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:137. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pranke IM, Sermet-Gaudelus I. Biosynthesis of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;52:26–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis HA, Zhao X, Wang C, Sauder JM, Rooney I, Noland BW, Lorimer D, Kearins MC, Conners K, Condon B, Maloney PC, Guggino WB, Hunt JF, Emtage S. Impact of the deltaF508 mutation in first nucleotide-binding domain of human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator on domain folding and structure. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1346–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis HA, Wang C, Zhao X, Hamuro Y, Conners K, Kearins MC, Lu F, Sauder JM, Molnar KS, Coales SJ, Maloney PC, Guggino WB, Wetmore DR, Weber PC, Hunt JF. Structure and dynamics of NBD1 from CFTR characterized using crystallography and hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:406–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qu BH, Strickland EH, Thomas PJ. Localization and suppression of a kinetic defect in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator folding. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15739–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He L, Aleksandrov LA, Cui L, Jensen TJ, Nesbitt KL, Riordan JR. Restoration of domain folding and interdomain assembly by second-site suppressors of the DeltaF508 mutation in CFTR. Faseb J. 2010;24:3103–12. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-141788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeCarvalho AC, Gansheroff LJ, Teem JL. Mutations in the nucleotide binding domain 1 signature motif region rescue processing and functional defects of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator delta f508. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35896–905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teem JL, Carson MR, Welsh MJ. Mutation of R555 in CFTR-delta F508 enhances function and partially corrects defective processing. Receptors Channels. 1996;4:63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teem JL, Berger HA, Ostedgaard LS, Rich DP, Tsui LC, Welsh MJ. Identification of revertants for the cystic fibrosis delta F508 mutation using STE6-CFTR chimeras in yeast. Cell. 1993;73:335–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90233-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleizen B, van Vlijmen T, de Jonge HR, Braakman I. Folding of CFTR is predominantly cotranslational. Mol Cell. 2005;20:277–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadlish H, Skach WR. Biogenesis of CFTR and other polytopic membrane proteins: new roles for the ribosome-translocon complex. J Membr Biol. 2004;202:115–26. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0715-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cui L, Aleksandrov L, Chang XB, Hou YX, He L, Hegedus T, Gentzsch M, Aleksandrov A, Balch WE, Riordan JR. Domain interdependence in the biosynthetic assembly of CFTR. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:981–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du K, Lukacs GL. Cooperative assembly and misfolding of CFTR domains in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1903–15. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Venable J, LaPointe P, Hutt DM, Koulov AV, Coppinger J, Gurkan C, Kellner W, Matteson J, Plutner H, Riordan JR, Kelly JW, Yates JR, 3rd, Balch WE. Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Cell. 2006;127:803–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolb VA, Makeyev EV, Kommer A, Spirin AS. Cotranslational folding of proteins. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;73:1217–20. doi: 10.1139/o95-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolb VA, Makeyev EV, Spirin AS. Folding of firefly luciferase during translation in a cell-free system. Embo J. 1994;13:3631–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06670.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen W, Helenius J, Braakman I, Helenius A. Cotranslational folding and calnexin binding during glycoprotein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6229–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergman LW, Kuehl WM. Co-translational modification of nascent immunoglobulin heavy and light chains. J Supramol Struct. 1979;11:9–24. doi: 10.1002/jss.400110103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frydman J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Hartl FU. Co-translational domain folding as the structural basis for the rapid de novo folding of firefly luciferase. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:697–705. doi: 10.1038/10754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Netzer WJ, Hartl FU. Recombination of protein domains facilitated by co-translational folding in eukaryotes. Nature. 1997;388:343–9. doi: 10.1038/41024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Oh JM, Kim IW, Sauna ZE, Calcagno AM, Ambudkar SV, Gottesman MM. A “silent” polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity. Science. 2007;315:525–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1135308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bercovitch L, Terry P. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum 2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:S13–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angov E. Codon usage: nature’s roadmap to expression and folding of proteins. Biotechnol J. 2011;6:650–9. doi: 10.1002/biot.201000332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou M, Guo J, Cha J, Chae M, Chen S, Barral JM, Sachs MS, Liu Y. Non-optimal codon usage affects expression, structure and function of clock protein FRQ. Nature. 2013;495:111–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fath S, Bauer AP, Liss M, Spriestersbach A, Maertens B, Hahn P, Ludwig C, Schafer F, Graf M, Wagner R. Multiparameter RNA and codon optimization: a standardized tool to assess and enhance autologous mammalian gene expression. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Popp MW, Maquat LE. Organizing principles of mammalian nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Annu Rev Genet. 2013;47:139–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schweingruber C, Rufener SC, Zund D, Yamashita A, Muhlemann O. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay - mechanisms of substrate mRNA recognition and degradation in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829:612–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang J, Kim YK. When a ribosome encounters a premature termination codon. BMB Rep. 2013;46:9–16. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2013.46.1.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kervestin S, Jacobson A. NMD: a multifaceted response to premature translational termination. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:700–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grote A, Hiller K, Scheer M, Munch R, Nortemann B, Hempel DC, Jahn D. JCat: a novel tool to adapt codon usage of a target gene to its potential expression host. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W526–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ban N, Nissen P, Hansen J, Moore PB, Steitz TA. The complete atomic structure of the large ribosomal subunit at 2.4 A resolution. Science. 2000;289:905–20. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bashan A, Agmon I, Zarivach R, Schluenzen F, Harms J, Pioletti M, Bartels H, Gluehmann M, Hansen H, Auerbach T, Franceschi F, Yonath A. High-resolution structures of ribosomal subunits: initiation, inhibition, and conformational variability. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2001;66:43–56. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2001.66.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mendell JT, Sharifi NA, Meyers JL, Martinez-Murillo F, Dietz HC. Nonsense surveillance regulates expression of diverse classes of mammalian transcripts and mutes genomic noise. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1073–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metze S, Herzog VA, Ruepp MD, Muhlemann O. Comparison of EJC-enhanced and EJC-independent NMD in human cells reveals two partially redundant degradation pathways. RNA. 2013;19:1432–48. doi: 10.1261/rna.038893.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muhlemann O, Eberle AB, Stalder L, Zamudio Orozco R. Recognition and elimination of nonsense mRNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:538–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buhler M, Steiner S, Mohn F, Paillusson A, Muhlemann O. EJC-independent degradation of nonsense immunoglobulin-mu mRNA depends on 3′ UTR length. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:462–4. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delpy L, Sirac C, Magnoux E, Duchez S, Cogne M. RNA surveillance down-regulates expression of nonfunctional kappa alleles and detects premature termination within the last kappa exon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7375–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305586101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eberle AB, Stalder L, Mathys H, Orozco RZ, Muhlemann O. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by spatial rearrangement of the 3′ untranslated region. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e92. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.LeBlanc JJ, Beemon KL. Unspliced Rous sarcoma virus genomic RNAs are translated and subjected to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay before packaging. J Virol. 2004;78:5139–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5139-5146.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuda D, Hosoda N, Kim YK, Maquat LE. Failsafe nonsense-mediated mRNA decay does not detectably target eIF4E-bound mRNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:974–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rajavel KS, Neufeld EF. Nonsense-mediated decay of human HEXA mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5512–9. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.16.5512-5519.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh G, Rebbapragada I, Lykke-Andersen J. A competition between stimulators and antagonists of Upf complex recruitment governs human nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Sun X, Qian Y, Maquat LE. Intron function in the nonsense-mediated decay of beta-globin mRNA: indications that pre-mRNA splicing in the nucleus can influence mRNA translation in the cytoplasm. RNA. 1998;4:801–15. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298971849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gardner LB. Hypoxic inhibition of nonsense-mediated RNA decay regulates gene expression and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3729–41. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02284-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stalder L, Muhlemann O. Processing bodies are not required for mammalian nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. RNA. 2009;15:1265–73. doi: 10.1261/rna.1672509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amrani N, Ganesan R, Kervestin S, Mangus DA, Ghosh S, Jacobson A. A faux 3′-UTR promotes aberrant termination and triggers nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nature. 2004;432:112–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Behm-Ansmant I, Gatfield D, Rehwinkel J, Hilgers V, Izaurralde E. A conserved role for cytoplasmic poly(A)-binding protein 1 (PABPC1) in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Embo J. 2007;26:1591–601. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ivanov PV, Gehring NH, Kunz JB, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. Interactions between UPF1, eRFs, PABP and the exon junction complex suggest an integrated model for mammalian NMD pathways. Embo J. 2008;27:736–47. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Silva AL, Ribeiro P, Inacio A, Liebhaber SA, Romao L. Proximity of the poly(A)-binding protein to a premature termination codon inhibits mammalian nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. RNA. 2008;14:563–76. doi: 10.1261/rna.815108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thibodeau PH, Richardson JM, 3rd, Wang W, Millen L, Watson J, Mendoza JL, Du K, Fischman S, Senderowitz H, Lukacs GL, Kirk K, Thomas PJ. The cystic fibrosis-causing mutation deltaF508 affects multiple steps in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35825–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rabeh WM, Bossard F, Xu H, Okiyoneda T, Bagdany M, Mulvihill CM, Du K, di Bernardo S, Liu Y, Konermann L, Roldan A, Lukacs GL. Correction of both NBD1 energetics and domain interface is required to restore DeltaF508 CFTR folding and function. Cell. 2012;148:150–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Serohijos AW, Hegedus T, Riordan JR, Dokholyan NV. Diminished self-chaperoning activity of the DeltaF508 mutant of CFTR results in protein misfolding. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qu BH, Thomas PJ. Alteration of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator folding pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7261–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Du K, Sharma M, Lukacs GL. The DeltaF508 cystic fibrosis mutation impairs domain-domain interactions and arrests post-translational folding of CFTR. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:17–25. doi: 10.1038/nsmb882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen EY, Bartlett MC, Loo TW, Clarke DM. The DeltaF508 mutation disrupts packing of the transmembrane segments of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39620–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosser MF, Grove DE, Chen L, Cyr DM. Assembly and misassembly of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator: folding defects caused by deletion of F508 occur before and after the calnexin-dependent association of membrane spanning domain (MSD) 1 and MSD2. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4570–9. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-04-0357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thibodeau PH, Brautigam CA, Machius M, Thomas PJ. Side chain and backbone contributions of Phe508 to CFTR folding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:10–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Rescue of DeltaF508 and other misprocessed CFTR mutants by a novel quinazoline compound. Mol Pharm. 2005;2:407–13. doi: 10.1021/mp0500521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van Goor F, Straley KS, Cao D, Gonzalez J, Hadida S, Hazlewood A, Joubran J, Knapp T, Makings LR, Miller M, Neuberger T, Olson E, Panchenko V, Rader J, Singh A, Stack JH, Tung R, Grootenhuis PD, Negulescu P. Rescue of DeltaF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L1117–30. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y, Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Additive effect of multiple pharmacological chaperones on maturation of CFTR processing mutants. Biochem J. 2007;406:257–63. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang Y, Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Correctors promote maturation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-processing mutants by binding to the protein. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33247–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang X, Koulov AV, Kellner WA, Riordan JR, Balch WE. Chemical and biological folding contribute to temperature-sensitive DeltaF508 CFTR trafficking. Traffic. 2008;9:1878–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bebok Z, Venglarik CJ, Panczel Z, Jilling T, Kirk KL, Sorscher EJ. Activation of DeltaF508 CFTR in an epithelial monolayer. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C599–607. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang Y, Janich S, Cohn JA, Wilson JM. The common variant of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is recognized by hsp70 and degraded in a pre-Golgi nonlysosomal compartment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9480–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pind S, Riordan JR, Williams DB. Participation of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone calnexin (p88, IP90) in the biogenesis of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12784–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Loo MA, Jensen TJ, Cui L, Hou Y, Chang XB, Riordan JR. Perturbation of Hsp90 interaction with nascent CFTR prevents its maturation and accelerates its degradation by the proteasome. Embo J. 1998;17:6879–87. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Meacham GC, Lu Z, King S, Sorscher E, Tousson A, Cyr DM. The Hdj-2/Hsc70 chaperone pair facilitates early steps in CFTR biogenesis. Embo J. 1999;18:1492–505. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Okiyoneda T, Harada K, Takeya M, Yamahira K, Wada I, Shuto T, Suico MA, Hashimoto Y, Kai H. Delta F508 CFTR pool in the endoplasmic reticulum is increased by calnexin overexpression. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:563–74. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lukacs GL, Mohamed A, Kartner N, Chang XB, Riordan JR, Grinstein S. Conformational maturation of CFTR but not its mutant counterpart (delta F508) occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and requires ATP. Embo J. 1994;13:6076–86. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ward CL, Kopito RR. Intracellular turnover of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Inefficient processing and rapid degradation of wild-type and mutant proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25710–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang F, Kartner N, Lukacs GL. Limited proteolysis as a probe for arrested conformational maturation of delta F508 CFTR. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:180–3. doi: 10.1038/nsb0398-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza DW, White GA, O’Riordan CR, Smith AE. Defective intracellular transport and processing of CFTR is the molecular basis of most cystic fibrosis. Cell. 1990;63:827–34. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ward CL, Omura S, Kopito RR. Degradation of CFTR by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cell. 1995;83:121–7. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jensen TJ, Loo MA, Pind S, Williams DB, Goldberg AL, Riordan JR. Multiple proteolytic systems, including the proteasome, contribute to CFTR processing. Cell. 1995;83:129–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Denning GM, Anderson MP, Amara JF, Marshall J, Smith AE, Welsh MJ, Ostedgaard LS. Processing of mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is temperature-sensitive. Nature. 1992;358:761–4. doi: 10.1038/358761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dalemans W, Barbry P, Champigny G, Jallat S, Dott K, Dreyer D, Crystal RG, Pavirani A, Lecocq JP, Lazdunski M. Altered chloride ion channel kinetics associated with the delta F508 cystic fibrosis mutation. Nature. 1991;354:526–8. doi: 10.1038/354526a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yu W, Kim Chiaw P, Bear CE. Probing Conformational Rescue Induced by a Chemical Corrector of F508del-Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) Mutant. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:24714–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.239699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim Chiaw P, Wellhauser L, Huan LJ, Ramjeesingh M, Bear CE. A chemical corrector modifies the channel function of F508del-CFTR. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:411–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.065862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wellhauser L, Kim Chiaw P, Pasyk S, Li C, Ramjeesingh M, Bear CE. A small-molecule modulator interacts directly with deltaPhe508-CFTR to modify its ATPase activity and conformational stability. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:1430–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.055608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sato S, Ward CL, Krouse ME, Wine JJ, Kopito RR. Glycerol reverses the misfolding phenotype of the most common cystic fibrosis mutation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:635–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Welch WJ, Brown CR. Influence of molecular and chemical chaperones on protein folding. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1996;1:109–15. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1996)001<0109:iomacc>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brown CR, Hong-Brown LQ, Biwersi J, Verkman AS, Welch WJ. Chemical chaperones correct the mutant phenotype of the delta F508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1996;1:117–25. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1996)001<0117:ccctmp>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang Y, Bartlett MC, Loo TW, Clarke DM. Specific rescue of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator processing mutants using pharmacological chaperones. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:297–302. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hutt DM, Herman D, Rodrigues AP, Noel S, Pilewski JM, Matteson J, Hoch B, Kellner W, Kelly JW, Schmidt A, Thomas PJ, Matsumura Y, Skach WR, Gentzsch M, Riordan JR, Sorscher EJ, Okiyoneda T, Yates JR, 3rd, Lukacs GL, Frizzell RA, Manning G, Gottesfeld JM, Balch WE. Reduced histone deacetylase 7 activity restores function to misfolded CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:25–33. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grove DE, Fan CY, Ren HY, Cyr DM. The endoplasmic reticulum-associated Hsp40 DNAJB12 and Hsc70 cooperate to facilitate RMA1 E3-dependent degradation of nascent CFTRDeltaF508. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:301–14. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-09-0760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Strickland E, Qu BH, Millen L, Thomas PJ. The molecular chaperone Hsc70 assists the in vitro folding of the N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25421–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sun F, Mi Z, Condliffe SB, Bertrand CA, Gong X, Lu X, Zhang R, Latoche JD, Pilewski JM, Robbins PD, Frizzell RA. Chaperone displacement from mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator restores its function in human airway epithelia. Faseb J. 2008;22:3255–63. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-105338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Suaud L, Miller K, Panichelli AE, Randell RL, Marando CM, Rubenstein RC. 4-Phenylbutyrate stimulates Hsp70 expression through the Elp2 component of elongator and STAT-3 in cystic fibrosis epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:45083–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.293282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Riordan JR. Assembly of functional CFTR chloride channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:701–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Matsumura Y, David LL, Skach WR. Role of Hsc70 binding cycle in CFTR folding and endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:2797–809. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hutt DM, Powers ET, Balch WE. The proteostasis boundary in misfolding diseases of membrane traffic. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2639–46. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Powers ET, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW, Balch WE. Biological and chemical approaches to diseases of proteostasis deficiency. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:959–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.114844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3. Cold Spring Harbor Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4350–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Thomas PS. Hybridization of denatured RNA and small DNA fragments transferred to nitrocellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:5201–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.9.5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wong ML, Medrano JF. Real-time PCR for mRNA quantitation. Biotechniques. 2005;39:75–85. doi: 10.2144/05391RV01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schmittgen TD, Zakrajsek BA, Mills AG, Gorn V, Singer MJ, Reed MW. Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction to study mRNA decay: comparison of endpoint and real-time methods. Anal Biochem. 2000;285:194–204. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lu S, Wang A, Dong Z. A novel synthetic compound that interrupts androgen receptor signaling in human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2057–64. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Adebamiro A, Cheng Y, Rao US, Danahay H, Bridges RJ. A segment of gamma ENaC mediates elastase activation of Na+ transport. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:611–29. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.