Abstract

Autophagic vacuolar myopathies (AVMs) are an emerging group of muscle diseases with common pathologic features. These include autophagic vacuoles containing both lysosomal and autophagosomal proteins sometimes lined with sarcolemmal proteins such as dystrophin. These features have been most clearly described in patients with Danon’s disease due to LAMP2 deficiency and X-linked myopathy with excessive autophagy (XMEA) due to mutations in VMA21. Disruptions of these proteins lead to lysosomal dysfunction and subsequent autophagic vacuolar pathology. We performed whole exome sequencing on two families with autosomal dominantly inherited myopathies with autophagic vacuolar pathology and surprisingly identified a p.R454W tail domain mutation and a novel p.S6W head domain mutation in desmin, DES. In addition, re-evaluation of muscle tissue from another family with a novel p.I402N missense DES mutation also identified autophagic vacuoles. We suggest that autophagic vacuoles may be an underappreciated pathology present in desminopathy patient muscle. Moreover, autophagic vacuolar pathology can be due to genetic etiologies unrelated to primary defects in the lysosomes or autophagic machinery. Specifically, cytoskeletal derangement and the accumulation of aggregated proteins such as desmin may activate the autophagic system leading to the pathologic features of an AVM.

Keywords: Desmin, Myofibrillar Myopathy, Autophagy, Protein aggregation

Introduction

Autophagic vacuolar myopathies (AVM) are a spectrum of disorders unified by distinctive myopathologic features [1]. One unique pathology in AVMs is autophagic vacuoles with sarcolemmal features (AVSF) [2]. AVSF are sarcoplasmic vacuoles that contain lysosomal, autophagosomal and sarcolemmal membrane components [2]. AVSF pathology is a feature seen in Danon's disease, X-linked myopathy with excessive autophagy (XMEA), and infantile autophagic vacuolar myopathy [2]. Several genes have been identified as causing an AVM with AVSF myopathology and include LAMP2, VMA21, and more recently CLN3 [3–5]. Loss of function mutations in these three proteins is speculated to disrupt lysosomal function leading to AVSF pathology and muscle weakness.

While not being classified as AVMs, muscle disorders including myopathies with “rimmed vacuoles,” inclusion body myopathies and myofibrillar myopathies have autophagic pathology [6–8]. In these disorders, there is an accumulation of aggregated proteins in association with the accumulation of autophagic proteins such as microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) and the autophagic substrate SQSTM1/p62. In the case of valosin containing protein associated inclusion body myopathy (IBM), there is defect in autophagosome maturation leading to the accumulation of autophagic substrates and subsequent vacuolar pathology [8]. However, the genetic etiology of some AVMs remains unknown.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection and Evaluation

Families with muscle biopsies consistent with an AVM and an unknown genetic cause were identified from the Washington University Neuromuscular Clinic and Genetics Project. Charts, clinical records, and pathology slides were reviewed and available individuals seen for re-examination. All participants gave their written informed consent, and all study procedures were approved by the Human Studies Committee at Washington University.

Histochemistry and Immunohistochemistry

Muscle biopsy tissue was processed as previously described [7]. In brief, cryostat sections of rapidly frozen muscle were processed for muscle sections and fixed in acetone. Antibodies used were mouse anti-Dys3 (Santa Cruz), anti-α2-laminin (Santa Cruz), anti-LC3 (Sigma Chemical) and anti-Lamp2 (Santa Cruz).

Electron Microscopy

Fresh muscle tissue removed from the gastrocnemius or vastus lateralis muscles was fixed in modified Karnovsky's fixative of 3% glutaraldehyde and 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer. Tissue was post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 hour, en bloc stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate for 30 min, dehydrated in graded ethanols and propylene oxide and embedded in Spurr (Electron Microscopic Sciences, EMS). Tissue blocks were sectioned at ninety nanometers thickness, post stained with Venable's lead citrate and viewed with a JEOL model 1200EX electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Digital images were acquired using the AMT Advantage HR (Advanced Microscopy Technology, Danvers MA) high definition CCD, 1.3 megapixel TEM camera. Some images were taken using a JEOL 1400 TEM microscopes and images captured with a Gatan Orius 832 Digital Camera.

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) and HaloPlex targeted sequencing

Indexed genomic DNA (gDNA) libraries were prepared from patient gDNA using TruSeq DNA Preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and exome capture using TruSeq Exome Enrichment kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. For HaloPlex, Agilent’s SureDesign website was used to target the exons of 38 genes associated with neuromuscular disorders including DES. gDNA was prepared and captured according to HaloPlex manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 250ng of gDNA was digested in 8 parallel reactions, then hybridized with biotin-labeled probes designed to recognize and circularize targeted regions. Successfully circularized segments of gDNA were captured using streptavidin-coupled magnetic beads and amplified for sequencing. Sequencing was performed with 100bp paired-end reads on a HiSeq2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Reads from either WES or Haloplex sequencing were aligned to the human reference genome with NovoAlign (Novocraft Technologies, Selangor, Malaysia). Variants were called with SAMtools and annotated with SeattleSeq. Coverage across genomic intervals was calculated using BEDTools. Genomic coordinates for regions targeted by the whole-exome capture kit were provided by Illumina. Segregation and validation of mutations was assessed with standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based sequencing using Primer3Plus (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi) for primer design, an Applied Biosystems 3730 DNA Sequencer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for sequencing and LaserGene SeqMan Pro version 8.0.2 (DNAStar, Madison, WI) for tracing analysis.

Results

Genetic Analysis

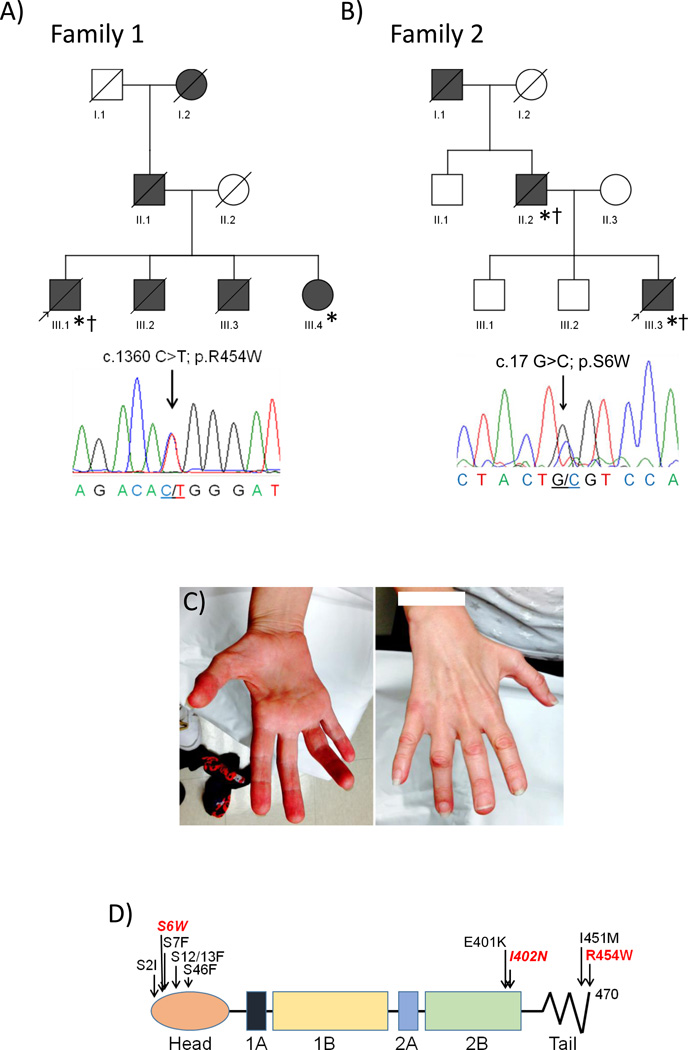

Two families with an autosomal dominantly inherited myopathy and cardiomyopathy with muscle biopsy features consistent with an AVM were identified in our clinic and whole exome sequencing (WES) on the probands from each family was performed. Family 1 was found to have a previously reported pathogenic c.1360C>T; p.R454W variant in the tail domain of desmin, DES (Figure 1A and 1D). This variant was also identified by WES in his affected sister. Sanger sequencing validated this variant in the proband and his affected sibling. WES of the proband from Family 2 failed to identify a rare, novel or previously reported pathogenic missense mutation in any gene associated with a neuromuscular or cardiac syndrome. However due to similarities in the muscle histopathology between Family 1 and Family 2, and potential concerns of low coverage across some areas of the genome (especially the first exon of DES) [9], we performed targeted sequencing of 38 neuromuscular genes that included LAMP2, VMA21, DES, MYOT, FLNC, VCP, LDB3, MATR3, BAG3, CRYAB, FHL1 and DNAJB6. Using this strategy, we identified a novel c.17G>C; p.S6W missense variant in DES (Figure 1B and 1D). This variant was not present in the Exome Variant Server (EVS) or dbSNP. Sanger sequencing validated this variant in the proband and his affected father.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of Family 1 (A) and Family 2 (B) are shown. Affected patients are in gray and arrow denotes proband; * indicates patients clinically examined; † indicates patients with muscle biopsies. Below each pedigree is a representative chromatogram of the forward sequencing reaction for the probands. C) Picture of the palmar and dorsal aspects of the right hand of patient III.4 from Family 1. Note profound thenar and hypothenar atrophy. D) Linear diagram of the desmin protein. Previously reported head and tail domain mutations are noted in black. The mutations identified in this study are denoted in red.

Clinical Description

Family 1

The proband of Family 1 was a 40 year old man with an 8 year history of progressive bilateral upper and lower extremity distal weakness. His symptoms began with increasing difficulty buttoning his clothes and picking up small objects. These symptoms progressed to difficulty with ambulation, climbing steps and rising from a chair. His past medical history was notable for cardiac failure due to mild global hypokinesis and an ejection fraction of 40%, biatrial enlargement and complete cardiac conduction block necessitating the placement of a ventricular pacer at the age of 39. Family history was notable for his father who died at the age of 34 with heart failure, his paternal grandmother who died at a “young age” also of heart failure, and two brothers (age 39 and 35) who are both deceased and one sister (age 42, see below) all with pacemaker placement for cardiac arrhythmia. Notably, his 35 year old brother was also being treated for distal lower extremity weakness and used ankle foot orthotics. On exam he had pronounced bilateral thenar and hypothenar atrophy. He had no facial weakness or scapular winging, however he did have 4/5 neck extensor weakness. Bilateral strength testing was as follows; 4+/5 shoulder abduction, 4+/5 wrist extension, 2/5 finger abduction, 4/5 ankle plantarflexion, 0/5 ankle dorsiflexion and 0/5 toe extension. Reflexes were 2+ at the biceps and patella but trace at the ankles with downgoing Babinskis bilaterally. Sensation was intact. He had a steppage gait. On laboratory testing, his creatine kinase (CK) was 289 (normal (nl) 30–200 u/L), his nerve conduction studies (NCSs) were normal while EMG revealed myopathic potentials with the presence of fibrillations and positive sharp waves in his distal musculature.

His sister presented to our clinic at the age of 42 with complaints of frequent falls, difficulty climbing stairs and bilateral hand weakness. Past medical history was notable for biventricular pacemaker placement at the age of 36 for complete heartblock. On exam she had prominent bilateral thenar and hypothenar atrophy (Figure 1C). She had mild bilateral lower facial weakness with 4/5 neck extensor weakness. Bilateral strength testing was notable for 4+/5 grip strength, 3/5 hand intrinsic strength, 3/5 dorsiflexion strength and 0/5 toe extensor strength. Her forced vital capacity (FVC) was 69% of predicted. Reflexes were 2+ and symmetric throughout with downgoing Babinskis bilaterally. Sensation was intact. Her gait was steppage. On laboratory testing her CK was 128 (nl 30–200 u/L).

Family 2

The proband of Family 2 was a 63 year old man with a twenty year history of both proximal and distal lower extremity weakness. He initially noted symmetric bilateral foot drop followed 6 months later with difficulty rising from a chair. His past medical history included type II diabetes and a recent hospital admission for congestive heart failure leading to the identification of a dilated cardiomyopathy with an ejection fraction of 28%. Family history was notable for his affected father (see below) and his paternal grandfather who also had frequent falls and tripping late in life. On exam he was wheelchair bound with 4−/5 bilateral deltoid strength, 4/5 bilateral bicep strength, 3+/5 bilateral triceps strength, 5/5 wrist extensor and 5/5 hand intrinsic strength. He was non-ambulatory and had no measurable strength in his bilateral lower extremities. He had no facial or neck weakness and no scapular winging. His FVC was 40% of predicted. Reflexes were 2+ in his biceps but absent in his patellas and ankles. Pinprick and cold sensation were diminished below his knees. Vibratory sensation and proprioception were normal. His NCSs were normal and his EMG revealed myopathic potentials with the presence of fibrillations and positive sharp waves. His CK was elevated at 809 (nl 30–200 u/L).

His father was evaluated at the age of 68 and endorsed a two year history of progressive leg weakness and frequent falls. His past medical history was notable for a dilated cardiomyopathy, atrial arrhythmias and type II diabetes. He had 5/5 strength throughout with the exception of 4+/5 bilateral hip flexion, 4−/5 bilateral ankle dorsiflexion and trace symmetric shoulder abduction weakness. He was unable to rise from a chair without using his hands for assistance. No neck flexor, facial weakness or scapular winging was noted. Reflexes were 2+ in his biceps and patella and 1+ at his ankles with negative Babinski signs. Sensation was intact. His NCSs were normal and his EMG revealed myopathic potentials with the presence of fibrillations and positive sharp waves. His CK was modestly elevated at 339 (nl 30–200 u/L).

Histopathologic and Immunohistopathologic Studies

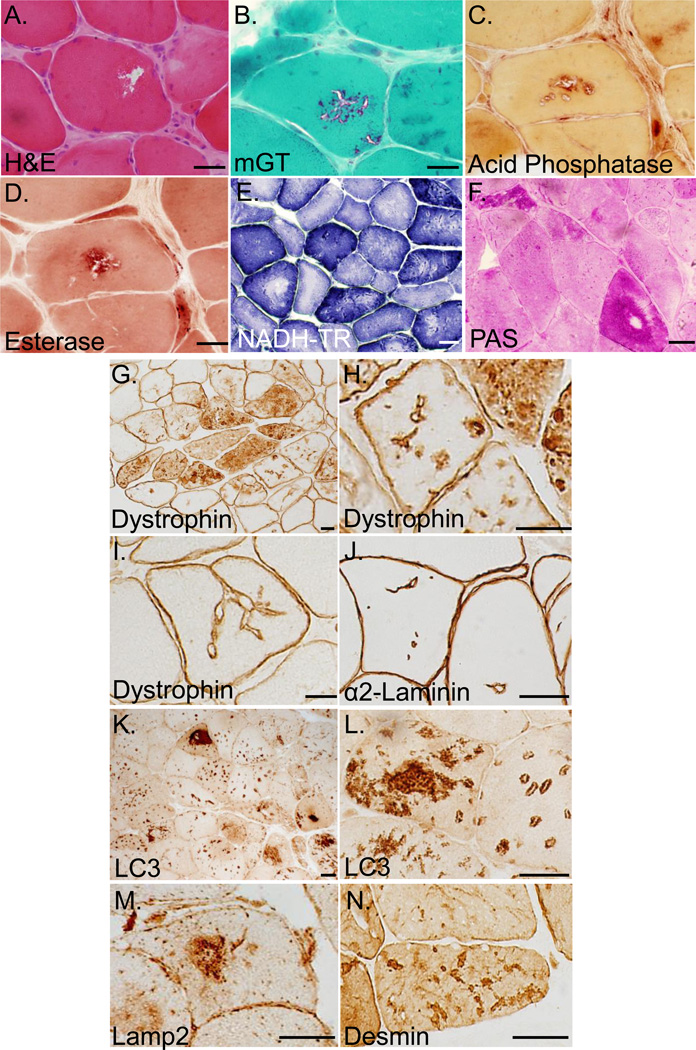

Muscle biopsy samples from the probands of Families 1 and 2 and two additional biopsies from father of the proband from family 2 were evaluated. Biopsies demonstrated marked variability in muscle fiber size along with fibers containing vacuoles and internal nuclei, rare fibers also had eosinophilic inclusions (Figure 2A). On modified gomori trichrome staining, red-rimmed vacuoles were seen in both large and small fibers (Figure 2B). Some vacuoles were positive for acid phosphatase (Figure 2C) and non-specific esterase (Figure 2D). Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide tetrazolium reductase (NADH-TR) staining showed disorganization of internal architecture, moth-eaten fibers, small accumulations of endomembrane (Figure 2E). Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining accumulated in some fibers but was notable absent from vacuolar structures (Figure 2F). Sarcolemmal membrane proteins including dystrophin, caveolin-3, α-, β-, δ-, γ-sarcoglycan and the sarcolemmal membrane associated protein α2-laminin were present at the sarcolemmal membrane but also had abnormal staining within the sarcoplasm as vacuolated structures or along invaginating sarcolemmal membranes in all four biopsies (not shown and Figure 2G–J). While vacuoles lined by sarcolemmal proteins were present in ~10% of fibers, autophagic markers such as LC3 (Figure 2K–L) and lysosome associated membrane protein-2 (Lamp2) (Figure 2M) were present as large intrasarcoplasmic inclusions or on vacuoles within >60% of myofibers. Desmin immunostaining was present as small and large aggregates throughout many fibers (Figure 2N). MHC class I expression was not increased on the plasma membrane of myofibers and C5b-9 complement immunostaining was only present in scattered necrotic fibers (not shown).

Figure 2.

A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of muscle from the proband of Family 1 (III.1); B) modified gomori trichrome staining of muscle from the proband of Family 2 (III.3); C) Acid phosphatase staining and D) non-specific esterase staining of vacuoles from the proband of family 2 (III.3); E) Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide tetrazolium reductase (NADH-TR) staining from the proband of Family 1 (III.1); F) Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining from the proband of Family 2 (III.1). G–H) Dystrophin immunhistochemistry of muscle from the father of the proband from Family 2 (II.2); I) Dystrophin immunohistochemistry from the proband of Family 1 (III.1); J) α2-laminin immunohistochemistry of muscle tissue from the proband of Family 2 (III.3); K–L) LC3 immunohistochemistry of muscle tissue from the proband of Family 2 (III.1); M) Lamp2 immunohistochemistry of muscle tissue from the proband of Family 1 (III.1); N) Desmin immunohistochemistry of muscle tissue from the proband of Family 2 (III.3). Scale Bar is 15uM.

Ultrastructural Analysis

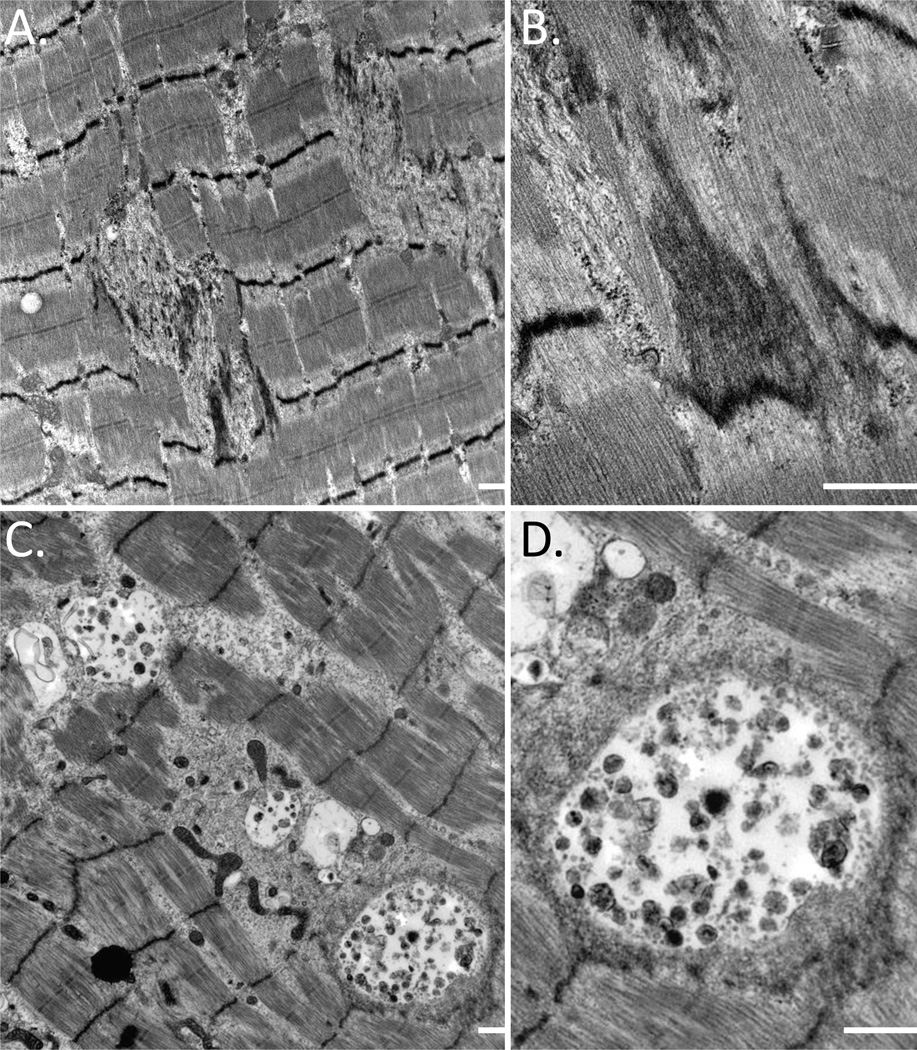

Electron microscopy was performed on skeletal muscle of three patients. All biopsies had the accumulation of granulofilamentous material between myofibrils and prominent Z-band streaming (Figure 3A and 3B). Aggregates of mitochondria, enlarged and abnormally shaped, were associated with increased numbers of lipid droplets. In addition, many fibers contained large vacuoles consistent with lysosomal and autophagic structures (Figure 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

A–B) Electron micrograph of skeletal muscle from the proband of Family 2 (III.3) demonstrating the accumulation of filamentous debris and Z-band streaming. C–D) Electron micrograph of skeletal muscle from the proband of Family 1 (III.1) with large autophagic vacuoles between myofibrils. Scale bar is 500 nM.

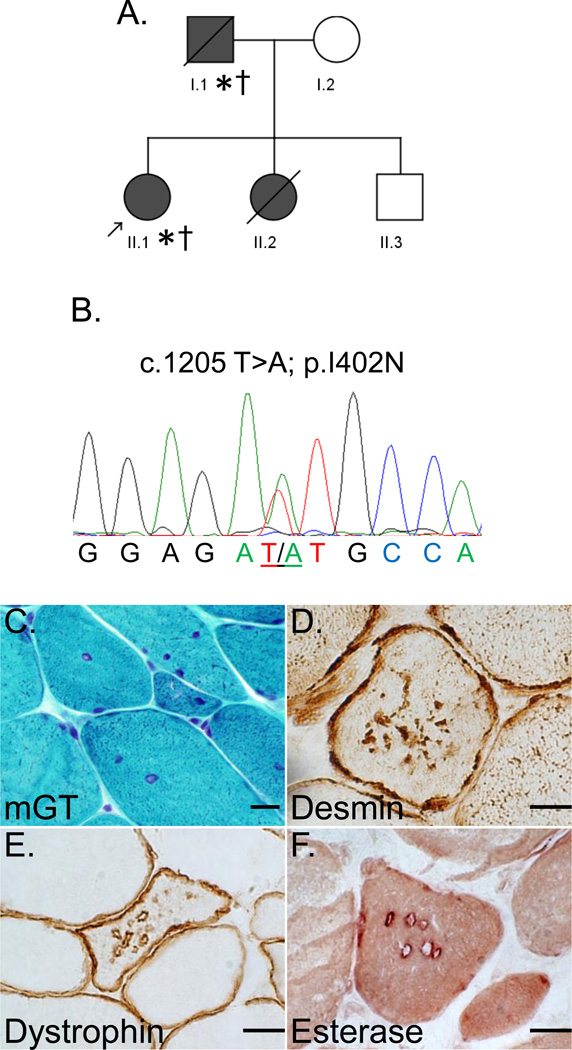

Re-evaluation of muscle pathology in a novel DES p.I402N family (Family 3)

To see if autophagic vacuoles similar to those in family 1 and 2 were present in other desminopathies and not isolated to these two mutations, we re-evaluated muscle tissue from a small two generation family with an autosomal dominantly inherited cardiomyopathy with respiratory insufficiency and desmin inclusions on muscle biopsy identified in our clinic (Figure 4A). WES of the proband from this family had previously identified a novel c.1205T>A; p.I402N missense DES variant (Figure 4B). This variant is unreported in EVS or dbSNP and lies within the evolutionarily conserved C-terminal region of the 2B domain of desmin [10]. The proband of Family 3 is a 33 year old Caucasian female with a dilated cardiomyopathy necessitating automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator placement and respiratory insufficiency. She has mild neck flexion and extension weakness and complains of dysphagia but is otherwise full strength. Her FVC is 59% of predicted and CK is 197 (nl 30–200 u/L). Similarly, her father who died of congestive heart failure at the age of 47 also had a cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, respiratory insufficiency (FVC 55% of predicted) and dysphagia. His CK was 382 (nl 30–200 u/L). Her sister died of sudden cardiac death at the age of 30. She has an unaffected 39 year old brother.

Figure 4.

A) Pedigree of Family 3. Affected patients are in grey and arrow denotes proband; * indicates patients clinically examined; † indicates patients with muscle biopsies. B) A representative chromatogram of the forward sequencing reaction for the proband. C) modified gomori trichrome staining of muscle from the proband of Family 3 (II.1); D) Desmin immunohistochemistry of muscle tissue from the proband of Family 3 (II.1); E) Dystrophin immunhistochemistry of muscle from the proband of Family 3 (II.1); F) non-specific esterase staining of vacuoles from the proband of Family 3 (II.1). Scale Bar is 15uM.

Both the proband and her father had deltoid muscle biopsies performed. Biopsies demonstrated variation in fiber size, fibers with internal nuclei and coarse internal architecture (Figure 4C). Notably, there was no clear evidence of vacuolation on routine histochemistry. Immunostaining revealed fibers with both subsarcolemmal and sarcoplasmic desmin inclusions consistent with a myofibrillar myopathy (Figure 4D). Surprisingly, similar to Family 1 and Family 2’s muscle biopsies, sarcolemmal membrane proteins including dystrophin, caveolin-3, α-, β-, δ-, γ-sarcoglycan and α2-laminin had abnormal staining within the sarcoplasm as vacuolated structures in scattered muscle fibers from the proband’s biopsy (not shown and Figure 4E). In addition, acid phosphatase marked some vacuoles and non-specific esterase was present at the limiting membrane of the sarcoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 4F).

Discussion

Autosomal dominantly inherited mutations in DES are associated with several clinical syndromes including limb-girdle weakness, scapuloperoneal dystrophy, distal myopathy and cardiomyopathy [11]. In many cases both myopathy and cardiomyopathy co-exist in the same patient. Desminopathies are unified by myofibrillar disarray and the accumulation of desmin in pathologically affected tissues. In fact desmin accumulation was identified in the muscle of patients prior to the genetic identification of DES mutations [12]. Other less common pathologic features include the ectopic accumulation of sarcolemmal proteins such as dystrophin and caveolin-3 and rimmed vacuoles [13, 14]. In this study, we identified three families with an autosomal dominant syndrome with myopathy and cardiomyopathy. Interestingly, muscle biopsies from two of these families led to their initial diagnosis of an AVM. This was principally due to the presence of vacuoles that were lined by sarcolemmal proteins and containing LC3 and Lamp2. This pattern of pathology on muscle biopsy in an autosomal dominantly inherited myopathy had not been previously described leading us to perform WES on the probands of these families.

Genetic mutations in proteins associated with the endolysosomal pathway (LAMP2, VMA21) are most commonly associated with autophagic vacuolar pathology [2, 3]. In addition, patients with Pompe disease, who are deficient in lysosomal α-glucosidase, an enzyme essential for the degradation of glycogen to glucose within the lysosome, have an AVM. Indeed, some studies have reported AVSF-like pathology in Pompe disease patient muscle biopsies [15]. Moreover, patients treated with colchicine or chloroquine, two drugs that affect endolysosomal function in skeletal muscle, develop an AVM. The vacuoles in both colchicine and chloroquine myopathy also have sarcolemmal membrane markers consistent with AVSF pathology [15, 16].

The defining features of an AVM with AVSF are of course sarcoplasmic vacuoles rimmed by sarcolemmal proteins [2]. Other features include esterase, acid phosphatase and acetylcholinesterase staining of the vacuoles either within the lumen (in the case of acid phosphatase) or on the interior limiting membrane [2]. In the case of XMEA, complement C5b-9 is present surrounding myofibers and has been postulated to be due to the release of hydrolytic enzymes and lysosomal contents from the adjacent myofibers [3]. Finally, ultrastructural evidence that the intrasarcoplasmic vacuoles have a clear basement membrane suggesting that the genesis of the vacuole was from the sarcolemma has been proposed as a diagnostic feature [2]. Our patients with DES mutations did not have all of these features and thus the autophagic vacuoles are AVSF-like. However, it was these types of vacuoles with prominent lysosomal, autophagosomal and sarcolemmal protein markers that led to the initial pathologic diagnosis of AVM in our two families.

AVM pathology likely encompasses a continuum of vacuoles that include “rimmed vacuoles,” autophagic vacuoles (marked by LC3), endolysosomal vacuoles (marked by lysosomal membrane proteins and acid phosphatase), AVSF-like pathology (containing autophagic markers and sarcolemmal proteins), AVSF pathology and AVSF pathology with complement deposition as is seen in XMEA. In many AVMs, the genetic etiology is due to a mutation in a protein necessary for autophago-lysosomal function. However in the case of our patients and other myofibrillar myopathies, a structural protein accumulates leading the autophagic pathology and some cases vacuoles that are reminiscent of AVSF. The mechanism of autophagic vacuoles containing sarcolemmal proteins is unclear. In the case of Danon’s Disease and XMEA, it has been postulated that lysosomal exocytosis may be dysregulated. These AVMs have mutations in LAMP2 and VMA21, proteins necessary for normal lysosomal function. How mutations in desmin or other myofibrillar proteins lead to AVSF-like pathology is intriguing. It is conceivable that aggregates of desmin secondarily lead to lysosomal dysfunction and reduced autophagic flux resulting in autophagic vacuoles. Alternatively, desmin aggregates may stimulate an intact autophagic system that either enhances autophagic flux or exhausts the autophagic system leading to vacuolar pathology. Studies designed to evaluate dynamic autophagic and lysosomal function in vivo are needed to explore this question.

We describe three pathogenic DES variants, two of which are previously unreported in the literature. The p.R454W desmin tail mutation has been previously reported in the literature in four different patients [17–19]. Among these four patients, one individual of North African descent manifested with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, distal weakness, bilateral ptosis and facial weakness with no family history [17]. In addition, this patient carried a p.Q74K missense variant in myotilin, however the pathogenicity of this variant is unlikely due to its MAF of ~6.3% in Northern African populations (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/). Another pair of siblings also had a p.R454W desmin tail mutation and both manifested with isolated arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) similar to Family 1 but without reported weakness [19]. There is no mention of autophagic pathology in any of these previously reported patients muscle biopsies. Family 1 in our study had autosomal dominant segregation of the p.R454W desmin variant in two clinically affected individuals with both ARVC and a distal myopathy further supporting its pathogenicity.

The novel head domain p.S6W DES variant identified in Family 2 is likely pathogenic because of the following: 1) the variant segregated with clinically affected individuals within the family and has not been reported in EVS or dbSNP; 2) the clinical syndrome in Family 2 is consistent with a desmin mutation, as is the accumulation of desmin aggregates within the muscle tissue; 3) several other known pathogenic mutations reside in the head domain of desmin and are similarly at serine residues. These include S2I [13], S7F [18], S12F [20], S13F [21, 22], and S46F/Y [13]; 4) Serine residues 6, 7 and 8 are reversibly phosphorylated and their mutation dominantly effects myofibrillogenesis in cell culture models [23]. 5) WES of this patient did not identify mutations in any other genes associated with myofibrillar myopathies or vacuolar myopathies including LAMP2, VMA21 or CLN3.

The p.I402N missense desmin variant identified in Family 3 has also not been previously reported in the literature or EVS and dbSNP. A pathogenic variant has been reported at an adjacent residue, E401K in a patient with muscle weakness, dysphagia and cardiomyopathy [10]. In addition, the E401K disrupted intermediate filament assembly in vitro [10]. The p.I402N desmin variant segregated with disease in two affected family members. Family 3 had a phenotype consistent with a desminopathy and muscle biopsy features of myopathy with desmin accumulation suggesting that the p.I402N variant is indeed pathogenic. Future studies evaluating the in vitro and in vivo functionality of both the p.S6W and p.I402N variants may further help define their pathogenic role.

The clinical phenotype of our families was strongly suggestive of a desminopathy because of the autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance associated with both cardiac and skeletal muscle dysfunction. In the case of Family 2 carrying the S6W DES variant, biopsies from two affected patients (including a second biopsy from the proband) demonstrated identical autophagic vacuolar pathology with desmin inclusions. Rimmed vacuoles have been described in primary desminopathy patients [13]; however, widespread vacuolar pathology is uncommon. One patient with vacuolar pathology and a c.735G>C DES variant has been reported, although the same vacuolar pathology was absent in another family member whom had “classical” myopathological features of a desminopathy [24]. Our initial genetic analysis via WES failed to identify a DES variant (discussed below) further complicating our diagnosis. The recognition of autophagic vacuolar pathology in primary desminopathies may aid in the diagnosis of unknown myopathies.

As mentioned, WES was able to identify the p.R454W and p.I402N variants in DES; however, it did not detect the p.S6W variant in DES because of limited coverage of the first exon. Due to the pathologic similarities between Family 1 and Family 2, we performed targeted capture and sequencing of genes associated with vacuolar and protein aggregate myopathies (including DES). Using this strategy, we identified the p.S6W DES variant in Family 2. This highlights a distinct problem with WES for some neuromuscular genes: the depth of sequence coverage is not uniform and can vary significantly from exon to exon even with the same gene. For example, in 6500 whole-exomes in EVS, the p.R454W variant is covered by an average of 53 reads while the sequence depth for the p.S6W variant is only 10 reads (Supplemental Figure 1A). In fact, visualization of the read depth over the coding exons of DES from the WES data of family 2 demonstrated that no sequence was captured over the base pairs encoding the serine residue at amino acid 6. This is likely due to the higher GC content of exon 1 but illustrates that some regions of important genes may be uninvestigated by WES.

In addition to dominant mutations in DES, dominantly inherited mutations in CRYAB cause a myofibrillar myopathy with desmin and αB-crystallin positive inclusions [25]. Some studies have demonstrated that mutant desmin or αB-crystallin inclusions activate the autophagosome-lysosome pathway [26, 27] whereas others have shown diminished autophagic activity [28]. Moreover studies have suggested that mutant αB-crystallin is not degraded via autophagy but instead via the ubiquitin protein system (UPS) [29]. Intriguingly, genetic activation of autophagy in a cardiac model of αB-crystallinopathy ameliorates cardiac disease and diminishes the volume of αB-crystallin aggregates [30]. The identification of an AVM with AVSF-like pathology in patients with DES mutations implies that indeed autophagic function is affected in primary desminopathy patient muscle. We suggest that autophagic function and its dysfunction are likely important mediators of myofibrillar myopathy pathogenesis and may be a tractable therapeutic target in the treatment of protein aggregate myopathies.

Supplementary Material

Graphs depicting sequencing coverage depth following exome capture across the 8 exons of the DES gene. A) Data was acquired from the exome variant server (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/). Note the heterozygous variant that was missed by exome sequencing is at chromosome 2:220283201 which corresponds to the c.17G of DES and has an average sequence depth of only 10 reads. The heterozygous variant that was identified by exome sequencing at chromosome 2:220290456 corresponds to the c.1360C of DES and has an average sequence depth of 53 reads. B) Read depth over the coding exons of DES from whole exome data for the proband of Family 2, visualized using Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV, version 2.3 Broad Institute). Note the heterozygous variant missed by exome sequencing is at chromosome 2:220283201 which corresponds to the c.17G of DES and has no sequencing reads. The heterozygous variant that was identified by exome sequencing at chromosome 2:220290456 corresponds to the c.1360C of DES and has an average sequence depth of > 100 reads.

Highlights.

We identified two patients with autophagic vacuolar pathology on muscle biopsy

Whole exome sequencing identifies novel Desmin mutations in two patients

Desminopathy patient skeletal muscle can have autophagic vacuolar pathology

Acknowledgements

NIH AG031867 (CCW), AG042095 (CCW), NS055980 (RHB), NS069669 (RHB), and NS075094 (MBH). The Muscular Dystrophy Association (CCW), the Myositis Association (CCW), and the Hope Center for Neurological Disorders (CCW and MBH). RHB holds a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- 1.Nishino I. Autophagic vacuolar myopathy. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugie K, Noguchi S, Kozuka Y, et al. Autophagic vacuoles with sarcolemmal features delineate Danon disease and related myopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:513–522. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramachandran N, Munteanu I, Wang P, et al. VMA21 deficiency prevents vacuolar ATPase assembly and causes autophagic vacuolar myopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:439–457. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortese A, Tucci A, Piccolo G, et al. Novel CLN3 mutation causing autophagic vacuolar myopathy. Neurology. 2014 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishino I, Fu J, Tanji K, et al. Primary LAMP-2 deficiency causes X-linked vacuolar cardiomyopathy and myopathy (Danon disease) Nature. 2000;406:906–910. doi: 10.1038/35022604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kley RA, Serdaroglu-Oflazer P, Leber Y, et al. Pathophysiology of protein aggregation and extended phenotyping in filaminopathy. Brain. 2012;135:2642–2660. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temiz P, Weihl CC, Pestronk A. Inflammatory myopathies with mitochondrial pathology and protein aggregates. J Neurol Sci. 2009;278:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ju JS, Fuentealba RA, Miller SE, et al. Valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for autophagy and is disrupted in VCP disease. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:875–888. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald KK, Stajich J, Blach C, Ashley-Koch AE, Hauser MA. Exome analysis of two limb-girdle muscular dystrophy families: mutations identified and challenges encountered. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goudeau B, Rodrigues-Lima F, Fischer D, et al. Variable pathogenic potentials of mutations located in the desmin alpha-helical domain. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:906–913. doi: 10.1002/humu.20351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemen CS, Herrmann H, Strelkov SV, Schroder R. Desminopathies: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:47–75. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1057-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goebel HH. Desmin-related myopathies. Curr Opin Neurol. 1997;10:426–429. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199710000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selcen D, Ohno K, Engel AG. Myofibrillar myopathy: clinical, morphological and genetic studies in 63 patients. Brain. 2004;127:439–451. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shinde A, Nakano S, Sugawara M, et al. Expression of caveolar components in primary desminopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Bleecker JL, Engel AG, Winkelmann JC. Localization of dystrophin and beta-spectrin in vacuolar myopathies. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1200–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez C, Figarella-Branger D, Alla P, Harle JR, Pellissier JF. Colchicine myopathy: a vacuolar myopathy with selective type I muscle fiber involvement. An immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study of two cases. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;103:100–106. doi: 10.1007/s004010100434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bar H, Goudeau B, Walde S, et al. Conspicuous involvement of desmin tail mutations in diverse cardiac and skeletal myopathies. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:374–386. doi: 10.1002/humu.20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vattemi G, Neri M, Piffer S, et al. Clinical, morphological and genetic studies in a cohort of 21 patients with myofibrillar myopathy. Acta Myol. 2011;30:121–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otten E, Asimaki A, Maass A, et al. Desmin mutations as a cause of right ventricular heart failure affect the intercalated disks. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1058–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong D, Wang Z, Zhang W, et al. A series of Chinese patients with desminopathy associated with six novel and one reported mutations in the desmin gene. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37:257–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pica EC, Kathirvel P, Pramono ZA, Lai PS, Yee WC. Characterization of a novel S13F desmin mutation associated with desmin myopathy and heart block in a Chinese family. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergman JE, Veenstra-Knol HE, van Essen AJ, et al. Two related Dutch families with a clinically variable presentation of cardioskeletal myopathy caused by a novel S13F mutation in the desmin gene. Eur J Med Genet. 2007;50:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollrigl A, Hofner M, Stary M, Weitzer G. Differentiation of cardiomyocytes requires functional serine residues within the amino-terminal domain of desmin. Differentiation. 2007;75:616–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clemen CS, Fischer D, Reimann J, et al. How much mutant protein is needed to cause a protein aggregate myopathy in vivo? Lessons from an exceptional desminopathy. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E490–E499. doi: 10.1002/humu.20941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vicart P, Caron A, Guicheney P, et al. A missense mutation in the alphaB-crystallin chaperone gene causes a desmin-related myopathy. Nat Genet. 1998;20:92–95. doi: 10.1038/1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tannous P, Zhu H, Johnstone JL, et al. Autophagy is an adaptive response in desmin-related cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9745–9750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706802105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Q, Su H, Ranek MJ, Wang X. Autophagy and p62 in cardiac proteinopathy. Circ Res. 2011;109:296–308. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.244707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pattison JS, Osinska H, Robbins J. Atg7 induces basal autophagy and rescues autophagic deficiency in CryABR120G cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2011;109:151–160. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Rajasekaran NS, Orosz A, Xiao X, Rechsteiner M, Benjamin IJ. Selective degradation of aggregate-prone CryAB mutants by HSPB1 is mediated by ubiquitin-proteasome pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:918–930. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhuiyan MS, Pattison JS, Osinska H, et al. Enhanced autophagy ameliorates cardiac proteinopathy. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:5284–5297. doi: 10.1172/JCI70877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Graphs depicting sequencing coverage depth following exome capture across the 8 exons of the DES gene. A) Data was acquired from the exome variant server (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/). Note the heterozygous variant that was missed by exome sequencing is at chromosome 2:220283201 which corresponds to the c.17G of DES and has an average sequence depth of only 10 reads. The heterozygous variant that was identified by exome sequencing at chromosome 2:220290456 corresponds to the c.1360C of DES and has an average sequence depth of 53 reads. B) Read depth over the coding exons of DES from whole exome data for the proband of Family 2, visualized using Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV, version 2.3 Broad Institute). Note the heterozygous variant missed by exome sequencing is at chromosome 2:220283201 which corresponds to the c.17G of DES and has no sequencing reads. The heterozygous variant that was identified by exome sequencing at chromosome 2:220290456 corresponds to the c.1360C of DES and has an average sequence depth of > 100 reads.