Abstract

Exaggerated CD4+T helper 2-specific cytokine producing memory T cell responses developing concomitantly with a T helper1 response might have a detrimental role in immunity to infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). To assess the dynamics of antigen (Ag)-specific memory T cell compartments in the context of filarial infection we used multiparameter flow cytometry on PBMCs from 25 microfilaremic filarial -infected (Inf) and 14 filarial-uninfected (Uninf) subjects following stimulation with filarial (BmA) or with the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)-specific Ag CFP10. Our data demonstrated that the Inf group not only had a marked increase in BmA-specific CD4+IL-4+ cells (Median net frequency compared to baseline (Fo)=0.09% vs. 0.01%, p=0.038) but also to CFP10 (Fo =0.16% vs. 0.007%, p=0.04) and Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B (SEB) (Fo =0.49% vs. 0.26%, p=0.04). The Inf subjects showed a BmA-specific expansion of CD4+CD45RO+IL-4+ producing central memory (TCM, CD45RO+CCR7+CD27+) (Fo =1.1% vs. 0.5%, p=0.04) as well as effector memory (TEM CD45RO+CCR7-CD27-) (Fo =1.5% vs. 0.2%, p=0.03) with a similar but non-significant response to CFP10. In addition, there was expansion of CD4+ IL-4+ CD45RA+ CCR7+CD27+ (naïve-like) in Inf individuals compared to Uninf subjects. Among Inf subjects with definitive latent tuberculosis , there were no differences in frequencies of IL-4 producing cells within any of the memory compartments compared to the Uninf group. Our data suggest that filarial infection induces antigen-specific, exaggerated IL-4 responses in distinct T cell memory compartments to Mtb-specific antigens, which are attenuated in subjects who are able to mount a delayed type hypersensitivity reaction to Mtb.

Introduction

Filarial parasites infect an estimated 200 million people worldwide and have complex life cycles with the capacity for chronic persistence in the lymphatics or subcutaneous tissues of humans. Patent filarial infections (i.e. establishment of the adult worms and subsequent microfilariae (MF) production) are able to induce profound parasite antigen-specific CD4+ T cell hyporesponsiveness that is felt to be IL-10 dependent but also may reflect expansion of the Th2-like CD4+ T cells (IL-4, IL-5)(1, 2).

This imbalanced parasite antigen-driven CD4+ T cell response seen in chronic filarial infections can impose modulation of bystander antigen responses as well (3, 4) and becomes particularly relevant in endemic areas where there is significant geographic overlap with TB, a infection that is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (5). The immune modulation caused by these filarial parasites is of particular relevance in the current global search for an effective TB vaccine, especially after it has been demonstrated that BCG is poorly protective for active pulmonary TB in parasite-endemic areas (6). Impaired cellular responses as well as increased antigen driven IL-4 production to PPD have previously been demonstrated in filarial infections (7, 8), but it is unclear how the parasite induced expansion of Th2 cell populations might affect CD4-specific memory responses to concurrent infections such as TB

It is also not well understood how these responses might be modulated in subjects who have the capability of generating a robust IFN-γ specific T cell recall response to Mtb-specific antigens due to prior exposure to the mycobacteria, a response that currently defines the clinical state of latent TB (LTBI) (9). Models of chronic viral infection have provided some insights into the generation and persistence of various memory T cell populations (10, 11) and some phenotypic characterization of memory populations in humans with chronic filarial infections has been done previously (12).

There is, however, a paucity of studies looking at functional antigen-specific immune responses of these memory populations in the setting of chronic helminth infections. Using recent advances in multi-parameter flow cytometry we sought to combine phenoytping with antigen specific cytokine production. We hypothesized that the filarial infection-induced expansion of specific CD4+ subtypes modulate the quality and nature of the CD4+ T cell responses to Mtb. To this end, we sought to examine specific memory CD4+ T cell responses to both filarial antigen and to Mtb-specific antigen (CFP10) in filarial-infected (Inf) individuals and in filarial-uninfected (Uninf) controls. Additionally, we compared the effect of having developed a delayed-type hypersensitivity response to Mtb-specific antigen (CFP10) on these responses by comparing subjects with or without LTBI in the Inf group. Our data provide the first detailed characterization of filarial infection induced antigen-specific, exaggerated IL-4 responses in specific T cell memory compartments to Mtb-specific antigens. We show, specifically, that this expansion predominantly affects early precursor cells with a naïve-like phenotype and that responses within this compartment are attenuated in subjects who are able to mount a delayed type hypersensitivity reaction to Mtb.

Materials and Methods

Study population

25 microfilaremic patients with Loa loa (Inf) were studied as were 14 filaria-uninfected healthy controls (Uninf) with no evidence of prior exposure to filarial infection (Table I). Inf individuals were from different countries of west and central Africa (Table I) while the healthy volunteers (Uninf) were US residents with no history of travel or exposure to filarial infections. All individuals were examined and samples collected as part of registered protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NCT00001230 and NCT00001345) for the filarial infected patients and of Department of Transfusion Medicine, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health (IRB# 99-CC-0168) for the healthy donors. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Study population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Inf | Uninf |

| Sample size (n) | 25 | 14 |

| Median Age (Range) | 34(24-62) | 45(25-81) |

| Sex (M/F) | 18/7 | 8/6 |

| Median duration of infection (Range) | 5(1-18) | - |

| Country infection acquired | Nigeria (5) Cameroon (10) Gabon (5) Central African Republic (1) Democratic Republic of Congo (4) |

- |

| Quantiferon TB Gold test (Positive/Negative/Indeterminate) |

6/9/10 | 0/9/5 |

| Median total WBC count | 7.08(4.08-18.4) | NA |

| Median Absolute Eosinophil count (Range) | 786 (410-1224) | NA |

| Positive IgE (units) | 9 | 0 |

| Median Microfilaria count (Range) | 180 (2-10,400) | 0 |

| BmA specific IgG4 (ng/ml) | 4978 (782-65950) | 0 |

Microfilaremia was detected in 1 ml of anticoagulated blood following previously established protocols (13). QuantiFERON TB-Gold In-Tube (Cellestis, Valencia, CA, (IGRA) was used to diagnose latent TB infection (LTBI). BmA-specific IgG4 and IgG ELISA were performed exactly as previously described (14). All filarial-infected donors had normal chest radiographs with no pulmonary symptoms (fever, cough, chest pain or hemoptysis).

Antigens and In Vitro Culture

Parasite antigen (BmA, obtained from saline extracts of B.malayi adult worms) and Mycobacterial antigen—culture filtrate protein-10 (CFP-10) (Fitzgerald Industries Intl. Inc., Acton, MA) were used as the antigenic stimuli. Final concentrations were 10 μg/ml for CFP-10. Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB) (Toxin Technology Inc., Sarasota, FL) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml was used as positive control. Cultures on peripheral blood mononuclear cells were performed to determine memory subsets and levels of intracellular cytokines. Briefly, cells were plated in RPMI, with 10% Fetal Calf Serum with penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/100 mg/ml), L-glutamine (2 mM) media at a maximum of 2×106/well, in a volume of 200 ul/well, in a 96-well round bottom plate with BmA, CFP-10 or SEB as well as media alone in the presence of α-CD28/CD49d beads (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 1 ug/ml, used as co-stimulatory molecules. After 2 hours of culture FastImmune™ Brefeldin A solution (1μg/ml) was added. Cells were cultured overnight (16-18 hrs) and were then harvested, washed and stained for flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry, Intracellular Cytokine Staining

Flow cytometry acquisition was performed on a modified LSRII instrument (BD biosciences) with 18 fluorescent parameter detection capabilities. Compensation and analysis of data was performed using Flowjo software (Treestar). Unlabeled antibodies were conjugated at the Immunotechnology Section, Vaccine Research Center, NIAID as previously reported http://www.drmr.com/abcon/ or purchased from BD Biosciences, eBioscience, Beckman Coulter and ReaMetrix. Surface and Intracellular staining was performed according to previously published protocols (15). A list of the antibodies used can be found in Supplemental Table I.

T cell phenoytping and cytokine production

Gating was performed on live single CD4+ cells. Naïve-like phenotype (NV) was identified as CD45RA+ CCR7+CD27+, RA+ T effector memory cells (TEMRA) memory cells as CD45RA+ CCR7− CD27−, central memory cells (TCM) as CD45RO+CCR7+CD27+ and effector memory cells (TEM) as CD45RO+CCR7−CD27−. Cytokine antibodies used were IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-4. All data are depicted as frequency of CD4+ T cells expressing cytokine(s). The gating strategy is presented in Supplemental Figure1.SEB-stimulated and unstimulated cells were used to set cut-off gates for cytokines. The cut-off for positive cytokine responses was 0.01 % of gated cells. Baseline values following media stimulation are depicted as absolute frequency, while frequencies following stimulation with antigens are depicted as net frequency (Antigen stimulated condition-unstimulated condition).

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using GraphPad PRISM (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Median frequencies were used for measurements of central tendency. Statistically significant differences between two groups were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s Multiple Comparison test was used for multiple comparisons.

Results

Study Populations

The Inf patients were all microfilariae positive with MF counts that ranged from 2-10400 mf/ml (median 180) whereas the Uninf were mf negative. As outlined in Table I, the Inf group had a gender distribution of 72% male and 28% female with age range of 24-62 (median 34) years. The filarial-uninfected (Uninf) group came from a subset of donors whose gender distribution was 57% male and 43%female with an age range of 25 – 81 (median 45) years. There was no difference in age and gender distribution between the 2 groups. For the Inf group, there was no elevation in total white blood cell (WBC) counts (median 7.08) or lymphocyte counts (not shown) but 18/25 had absolute eosinophil counts >500/ml (range 410-1224). Inf subjects had elevated BmA specific IgG4 (median 4978 ng/ml range: 782-65950); in contrast the controls had no measurable BmA-specific IgG4. None had any pulmonary symptoms or fever at the time of assessment and all subjects but two (with calcified nodules <7 mm) had normal chest X-ray finings (data not shown).IGRA were positive in 6 infected subjects, and none of the controls was positive. All subjects in Inf and Uninf groups were HIV negative. No differences were seen in frequencies of different CD4+ memory compartments (TCM, TEM, NV, TEMRA) between Inf and Uninf subjects (Table II). Therefore, age gender and wbc count distribution between Inf and Uninf subjects were noted to be broadly similar but Inf subjects were all microfilaremic (median count 180) and all had serologic evidence of filarial infection with 72% (18/25) having evidence of eosinophilia.

Table II.

CD4+ immune profile showing memory subsets in Inf and Uninf groups expressed as % CD4

| CD4+ T cell memory subsets | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ T cell memory profile [%CD4+ T cells] Median (Range) |

Inf | Uninf | P value |

| Naïve-like cells | 48.05 (12.10-72) | 37.10 (15- 64.30) |

p=0.14 |

| RA+ T effectors | 4.96(2.07-17.70) | 5.72 (1.69- 20.6) |

p=0.72 |

| Central Memory | 28.65 (15.4-41) | 29.8 (13.4- 49.5) |

p=0.45 |

| Effector Memory | 15.10(3.49-44.3) | 18.4 (7.42- 32.9) |

p=0.13 |

Naïve-like cells (CD45RA+CCR7+CD27+), RA+ T effectors (CD45RA+CCR7-CD27), Central Memory (CD45RO+CCR7+CD27+), Effector Memory (CD45RO+CCR7-CD27)

Filarial infection is associated with increased frequencies of IL-4 producing CD4+ T cells in response to filarial antigen (BmA) mycobacterial antigen (CFP10) and Staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB)

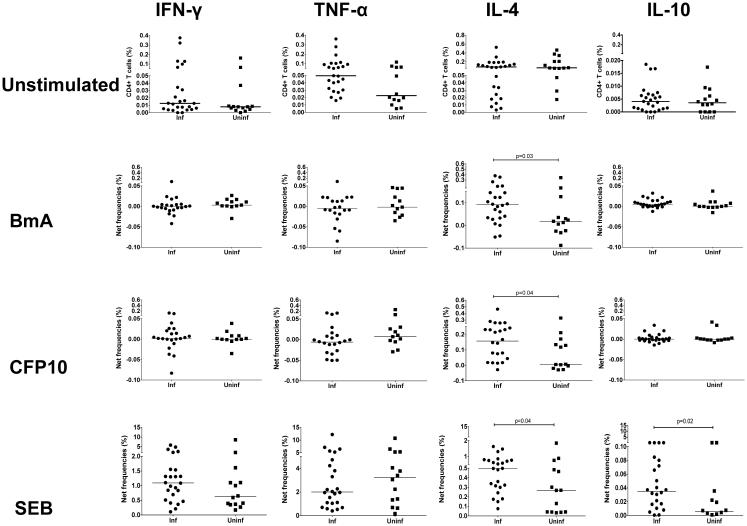

To delineate steady state as well as antigen driven CD4+ T cell cytokine- (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4 and IL-10) producing cells, we cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells with media alone as well as in response to stimulation by filaria-specific antigen (BmA), Mtb-specific antigen (CFP10) and superantigen SEB. Although at baseline no differences were noted between Inf and Uninf in the frequencies of CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ,TNF-α, IL-4 or IL-10 (Figure 1), in the Inf group, increased antigen induced frequencies of IL-4 producing CD4+ T cells (expressed as net frequency compared to baseline as defined above) were noted in response to BmA compared to the Uninf group (Median net frequency compared to baseline ( Fo)=0.09% vs. 0.01%, p=0.038). Similar differences were seen in CD4+IL-4+ frequencies, in response to CFP10 (Fo =0.16% vs. 0.007%, p=0.04) but also to SEB (Fo =0.49% vs. 0.26%, p=0.04). No differences were noted in the Fo of CD4+ IFN-γ+ cells between Inf and Uninf groups in response to either BmA, CFP10 or SEB. Although, at baseline a non-significant increase in the Fo of CD4+ TNF-α, producing cells were noted in the Inf (Fo=0.05%) vs. Uninf (Fo=0.024%), no differences were noted between groups in the antigen specific TNF-α response. Finally, increased CD4+IL-10+ frequencies were noted only in response to SEB in the Inf group (Fo=0.035%) compared to the Uninf group (Fo=0.005%) (p=0.027). Thus, although no differences were seen in the CD4+IL-4+ cell frequencies between groups at baseline, increased parasite and Mtb-antigen specific CD4+IL-4+ responses were noted in the Inf group compared to the Uninf group. These differences were also seen with SEB.

Figure1. Filarial infection is associated with filarial (BmA) as well as mycobacterial antigen (CFP10) and SEB induced increased frequencies of CD4+ cells producing IL-4.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cultured overnight with media alone or with BmA or CFP10 or SEB. Representative data are expressed as percent CD4+ cells expressing cytokines are shown as scatter plots in the top panel. Increase in CD4+ T cells producing IL-4 is expressed as net frequency (defined as antigen induced frequency-baseline frequency) in the Inf (n=25) and Uninf (n=14) groups are shown in response to BmA, CFP10 and SEB. Horizontal bars represent the median frequencies. P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test.

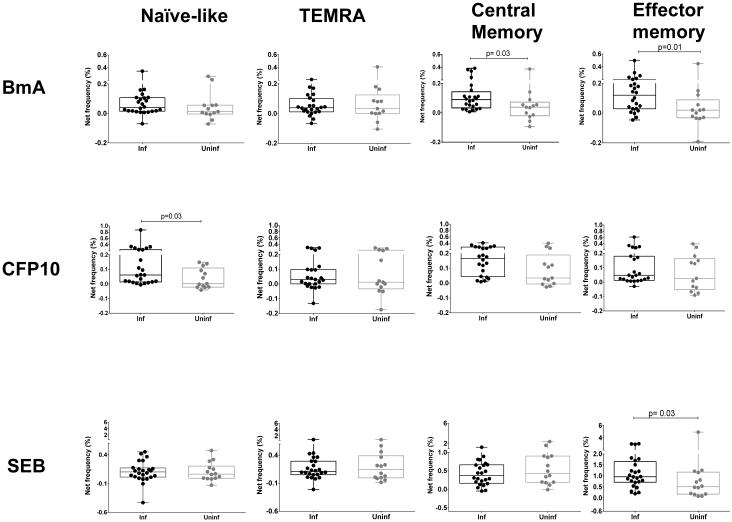

Antigen-specific IL-4 is induced in specific CD4+ T cell memory compartments

To further define the nature of the increased antigen driven IL-4 responses in CD4+ memory compartment we compared the frequencies of CD4+IL-4+ cells between infected subjects and uninfected controls in 4 different memory compartments (TCM, TEM, NV and TEMRA). As shown in figure 2 there was marked expansion of IL-4+CD4+ T cells in the central memory (TCM) compartment in the Inf group compared to Uninf (median net frequency (Fo )= 0.09% vs. 0.03%, p=0.029) and effector memory (TEM) compartment (Fo = 0.1% in Inf vs. 0.02% in Uninf, p=0.017) in response to BmA. Interestingly, a similar trend toward increased IL-4 production was also noted in cells with a Naïve-like (NV) phenotype (Fo= 0.03% in Inf vs. 0.01% in Uninf, p=0.12). Significantly increased IL-4 producing CD4+ cell frequencies were noted in the NV compartment in response to the Mtb-specific antigen CFP10 (Fo = 0.06% in Inf vs. 0.002% in Uninf, p=0.027) with similar but non-significant increases in frequencies of TCM and TEM IL-4 producing cells. In contrast, the increased IL-4 response to SEB was primarily limited to the TEM compartment (Fo= 0.96% in Inf vs. 0.51% in Uninf, p=0.03).In the Inf group, therefore, parasite and Mtb-antigen specific increase in CD4+IL-4+ frequencies was localized not only to TCM and TEM compartments but also within cells of a Naïve-like phenotype, a pattern not seen on non-specific T cell stimulation with SEB.

Figure2. BmA driven IL-4 expansion in filaria infected subjects occurs in TCM and TEM compartments in filaria infected subjects while CFP10 driven IL-4 expansion is primarily noted in NV cells, a pattern distinct from SEB induced expansion primarily in TEM cells.

Representative data are expressed as percent CD4+ cells expressing cytokines in the four different memory compartments, Naïve-like (NV), RA+ Effector T cells (TEMRA), Central memory (TCM) and Effector memory (TEM). Box and whisker plots represent median with 95% confidence intervals and individual dots representing each subject. Increase in CD4+ T cells producing IL-4 is expressed as net frequency (defined as antigen induced frequency-baseline frequency) in the Inf (n=25) and Uninf (n=14) groups are shown in response to BmA, CFP10 and SEB. Horizontal bars represent the median frequencies. P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test.

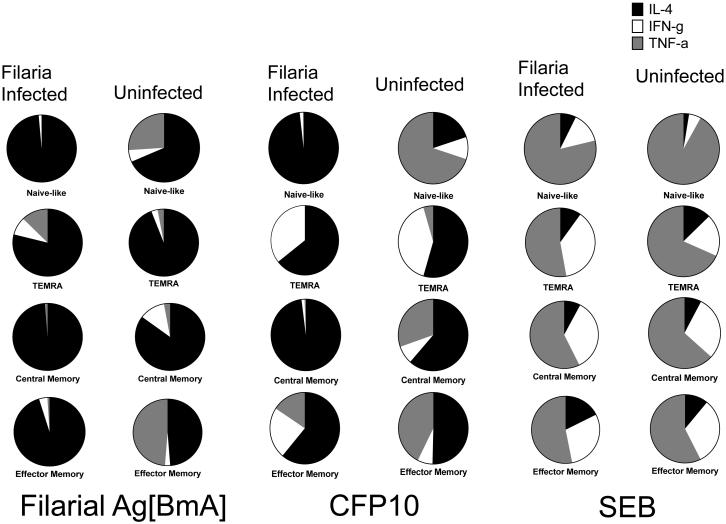

The pattern of preferential IL-4 expansion in the CD4+ memory compartment compared to Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ and TNF-α) showed similar trends in response to BmA and CFP10 but not to SEB

To delineate the Th1/Th2 cytokine milieu within each memory CD4+ T cell compartment, we performed a comparative assessment of the median net frequency (Fo) in antigen-specific frequencies of IL-4 with Th1-like cytokine (IFN-γ and TNF-α) producing CD4+ T cells in each individual memory compartments (Figure 3) between Inf and Uninf groups after adjusting for baseline expression. Within the TCM and TEM pool, in response to BmA an expansion primarily of IL-4 producing cells was noted primarily in the Inf group. The Fo in Inf compared to Uninf subjects in TCM was 0.09% vs. 0.03% (IL-4), 0.00085% vs. 0.004% (IFN-γ) and 0.001% vs. 0.001% (TNF-α) .Fo in TEM was 0.1% vs. 0.02% (IL-4), 0.004%vs. 0.001% (IFN-γ) and 0.001% vs. 0.02% (TNF-α). Similar results were seen in response to MTB-specific antigen CFP10 where the Fo in TCM in Inf vs. Uninf was 0.16% vs. 0.03% (IL-4), 0.002% vs. 0.004% (IFN-γ) and 0.001 vs. 0.01% (TNF-α) . In TEM Fo in Inf vs. Uninf was 0.03% vs. 0.02% (IL-4), 0.01% vs. 0.003% (IFN-γ) and 0.009% vs. 0.02% (TNF-α). In the CD4+ NV compartment, a primarily IL-4 dominant response to BmA was noted in both Inf and Uninf groups, the Fo, being 1.04% vs. 0.26% (IL-4) , 0.06% vs. 0.001% (IFN-γ) and 0.07 vs. 0.001%(TNF-α). CFP-10-specific responses showed a similar IL-4 dominance in the NV compartment in the Inf group with the Fo of 0.06% (IL-4) , 0.001% (IFN-γ) and 0.0001 %(TNF-α). Increased Fo of TNF-α producing cells were noted in the NV compartment in the Uninf group ,with Fo of 0.002% (IL-4), 0.001%(IFN-γ) and 0.007% (TNF-α). Moreover, in response to SEB, expansion of IFN-γ and TNF-α but not IL-4 producing cells was noted in both Inf and Uninf groups in TCM Fo of 0.37% vs. 0.43% for IL-4, 1.65% vs. 1.643% for IFN-γ and 2.72% vs. 3.57% for TNF-α. A similar result was seen in the NV compartment, Fo of 0.1% vs. 0.06% (IL-4), 0.19% vs. 0.12% (IFN-γ) and 1.09% vs.2.18% (TNF-α). The increased IL-4 response to SEB in the Inf group vs. the Uninf group was seen only in cells with a TEM phenotype (Fo = 0.96% vs. 0.51% for IL-4, 1.6% vs. 1.479 % for IFN-γ and 2.9% vs.2.6% for TNF-α.Therefore, when comparing the balance of Th1/Th2 responses to BmA and CFP10, in the Inf group, antigen specific IL-4 expansion occurred not only in the TEM pool but also in precursor memory populations (TCM) as well as the NV compartment, leading to diminished frequencies of Th1 cytokine producing cells whereas the Th1 response was largely intact in these compartments for the Uninf. The expansion of Th1 cytokines in response to T cell superantigen (SEB) in both groups demonstrated that there was no impairment of Th1 cytokine producing capacity in both groups.

Figure3. Filaria infected subjects show preferential IL-4 expansion (compared to IFN-γ and TNF-α) in the TCM and TEM compartments in response to BmA and CFP10. In the NV compartment Inf subjects have a dominant IL-4 response compared to Uninf subjects who have a dominant TNF-α response.

Data is represented as pie charts comparing median net frequency in CD4+ cytokine producing (IL-4, IFN-γ and TNF-α) cells as parts of the whole response in the different memory compartments (NV, TEMRA TCM, TEM,) between Inf (n=25) and Uninf (n=14) groups in response to BmA, CFP10 and SEB

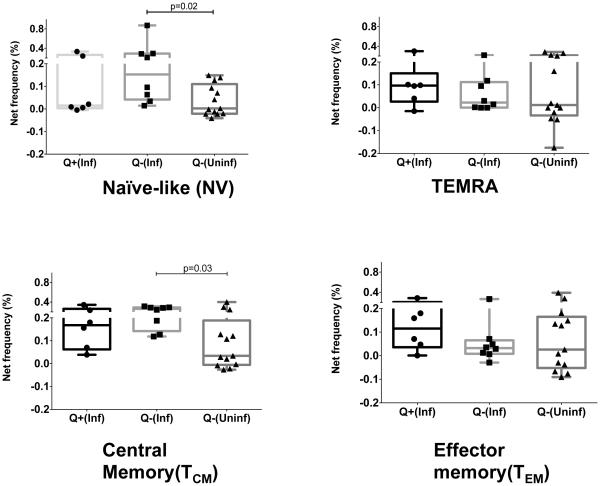

Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) positivity among the Inf group abrogated the increased IL-4 response to mycobacterial antigen

To test whether LTBI status (defined on the basis positive IRGA) in the Inf group makes any difference to the IL-4 response, we compared the net increase in IL-4 producing cell Fo in response to CFP10 (Figure 4) between those Inf subjects with LTBI( Q+Inf, n=6) and the Uninf (Q-Uninf, n=9) controls (who were IGRA negative). A similar comparison was performed between Inf subjects without LTBI (Q-Inf, n=7) and the Q-Uninf group. The increased IL-4 response in the NV compartment was maintained only in the Q-Inf (Fo=0.153%) group when compared to the Q-Uninf controls (Fo =0.002%, p=0.003). A similar IL-4 expansion was observed within the TCM compartment where the net frequency was 0.26% (Q-Inf) vs. 0.03% (Q-Uninf), (p=0.03).

Figure 4. LTBI status (defined as a positive QuantiFERON TB Gold test) in filaria-infected subjects abrogates the increased IL-4 response to CFP10 in the NV and TCM compartments.

Representative data are expressed as percent CD4+ cells expressing cytokines in the four different memory compartments, Naïve-like (NV), RA+ Effector T cells (TEMRA), Central memory (TCM) and Effector memory (TEM). Box and whisker plots represent median with 95% confidence intervals with individual dots representing each subject. Increase in CD4+ T cells producing IL-4 is expressed as net frequency (defined as antigen induced frequency-baseline frequency). Responses to CFP10 in healthy controls (Q-Uninf, n= 9) who were QuantiFERON TB Gold test negative (n=13) were compared separately with filaria infected subjects with positive (Q+Inf, n=6) and negative (Q-Inf, n= 7) QuantiFERON TB Gold test. Horizontal bars represent the median frequencies. P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test

The increased IL-4 response was not seen when Q+ Inf was compared to the Q-Uninf group for cells in the NV pool (Fo= 0.01% vs. 0.002% respectively) or in the TCM pool (Fo= 0.16% vs. 0.034% respectively). The CD4+ IL-4+ Fo in parasite infected subjects with indeterminate IGRA results (QInd, n=10), although not statistically significant, was increased in the NV compartment (Fo=0.05%) compared to the Q-Uninf (Fo=0.002%) but was not different in the TCM compartment (QInd Fo=0.029% vs. Q-Uninf Fo=0.03%). These data provide additional evidence that the antigen-specific IL-4 response in infected subjects was primarily derived from the NV compartment. No differences (data not shown) were noted between the QInd and Q-Uninf groups in CD4+ IL-4+ cells within TEMRA or TEM compartments. We conclude therefore, that parasite infected subjects who had the capacity to generate an optimal Th1 recall response by demonstrating IGRA positivity, showed concomitantly attenuated Th2 reponses as demonstrated by the decreased frequencies of CD4+IL-4+ cells in the TCM and in the NV compartment. Inf subjects who were IGRA negative or had indeterminate results on IGRA testing continued to have increased frequencies of CD4+IL-4+ cells in the NV compartment providing additional evidence that filarial infection might produce fundamental alterations in precursors of memory populations.

Discussion

One of the hallmarks of tissue invasive helminth infections in both humans and in animal models is the induction of an IL-4 dominated T cell response that occurs at the time the infection becomes patent (when fertilized adult female worms produce offspring – e.g. eggs in schistosomes, microfilariae in filarial infections). The present study clearly demonstrates that the expansion of IL-4 producing CD4+ T cells occurs in specific niches (central and effector memory) within the CD4+ memory T cell pool and that this IL-4 expansion affects CD4+ T cell memory responses to the Mtb-specific antigen CFP10 within the naïve-like CD4+ population. This pattern of pathogen-specific increased IL-4 production was distinct from the response elicited with SEB where primarily a typical effector memory response was observed. The antigen induced expansion of IL-4+CD4+ cells not surprisingly led to an alteration of the Th1/Th2 balance within these memory compartments. Similar trends were noted (data not shown) when we calculated the iMFI {computed by multiplying the relative frequency (percent positive) of cells expressing a particular cytokine with the MFI of that population}

Our study showed that adult subjects with Loa loa infection had an increased frequency of CD4+IL-4+ cells not only in response to filarial antigen BmA but also to Mtb-specific antigen CFP10.Chronic patent filarial infections are associated with impaired CD4+ T cell proliferative responses and it is well known that these infections, similar to other helminth infections (16, 17) induce an expansion of the Th2 response with down modulation of Th1-like responses (8, 18, 19). It has also been demonstrated that immunomodulation caused by helminths can led to exaggerated IL-4 responses to mycobacterial antigens like purified protein derivative (PPD) in endemic subjects infected with Onchocerca volvulus (8) as well as in a murine model where pre-immunization with live mf of Brugia malayi or with BmA skewed the PPD-specific response such that increased IL-4 and IL-5 were produced in addition to IFN-γ (20). Similar results were obtained with Loa loa infection but the intensity of the IL-4 response was life cycle stage specific with increased responses noted to adult and Mf stages compared to L3 Ag(21). In an adult B. malayi infected population, however, no increase in detectable IL-4 in response to PPD was seen which might reflect population differences in immune modulation by these parasites(22)

The role of an exaggerated IL-4 response in tuberculosis is still being elucidated. Murine models have failed to provide a consensus with exaggerated Th2 responses leading to pathology being demonstrated in the BALB/c model in some studies (23) while others have shown no difference in the control of Mtb infection in IL-4−/− as well as STAT6−/− mice (24). In human studies increased IL-4 gene expression in PBMCs has been shown to correlate with severity of symptoms as well as with the extent of radiographic disease and number of cavities (25). In addition, increased IL-4 levels detected in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid correlate positively with sputum smear positivity (26). However, whether background Th2 expansion in humans as might happen in chronic filarial infections leads to increased susceptibility to Mtb will need large prospective studies that are challenging to perform. Nevertheless, it is tempting to speculate that an optimal vaccine against Mtb will have to not only induce an effective Th1 response as has been suggested from animal model studies (27, 28). but also be able to modulate a Th2 response. It was interesting to note that the six subjects in the Uninf group who had exaggerated IL-4 responses were all IGRA negative and were among those who had minimal Th1 type responses with low frequencies of CD4+ IFN-γ+ and CD4+ TNF-α+ positive cells. Heightened IL-4 production might possibly have been the default response of these subjects who had no evidence of prior exposure to TB.

Recent advances in flow cytometry have allowed for phenotypic characterization of memory T cells using a well-defined set of markers. The CD45 (CD45RA and CD45RO) isoforms have been successfully used since the 1980s to distinguish naïve human T cells from memory cells with CD45RO being preferentially expressed on memory cells (29, 30). In addition, we further delineated subpopulations within each group using CD27, a member of the TNF receptor superfamily and C-C chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) to define memory and effector populations using a standardized set of criteria (31). Although, the role of memory CD4+ T cells in long-term protection against chronic infections is not quite clear, long-lived CD4+ memory responses have been demonstrated in chronic human viral infections (32, 33). We did not see any differences in the ex vivo frequencies of individual memory populations as has been demonstrated previously in subjects with chronic W. bancrofti infection (12). Combining phenotype with functionality, however, as was done in our study might be more relevant for infections like TB that depend directly on the effector function of CD4+ cells as this might have implications for vaccination (34). A limitation of our study, however, similar to other studies on human memory cells is the selective sampling of the peripheral blood compartment. This might underestimate tissue-specific immune responses that are probably more predictive of outcome in infections such as TB.

Given the heterogeneity of memory CD4+ T cell populations, the specific memory subsets that might play a role in protection against TB are still being defined. In this regard it has been demonstrated that a TEM population dominates in subjects previously treated with anti-tuberculous chemotherapy (35). Additionally, a higher frequency of the CD45RA-CD27- effector phenotype with high PD-1 expression was seen in subjects with latent TB when compared with BCG vaccinated individuals where a CD27+ early stage population was dominant (36). CD4+ cells with a naïve-like phenotype (CD44lo CD62Lhi) have been described to confer protection to low dose aerosol challenge on adoptive transfer to Rag−/− mice (37). Whether these cells have the phenotype of the recently described memory cells with stem cell like properties (38) remains to be determined. Selective Mtb-antigen specific Th2 expansion instead of protective Th1responses within cells with a naïve-like phenotype as seen in the parasite infected subjects might therefore have important implications in developing protective immunity to TB and optimal Mtb-specific vaccine response.

The generation and maintenance of an IL-4 specific Th2 memory pool and its specific role in different infectious states remains even less well understood. It has been demonstrated in vitro that the Th2 phenotype, once generated can persist stably and irreversibly by repression of IL-12 receptor signaling (39) and that a short duration of Th2 development can generate memory populations with high level Th2 cytokine production capabilities on recall activation (40). Persistence of Th2 memory with increased IL-4 responses on reinfection has been well demonstrated using IL-4 reporter mice infected with the gastrointestinal nematodes Heligmosomoides polygyrus (41) and Trichuris muris (42) even after clearance of parasite. Our study clearly demonstrates an increased antigen driven IL-4 specific responses in the TCM as well as the TEM compartment to parasite antigen with a similar trend when stimulated with the Mtb-specific antigen CFP10.

Interestingly, an increased IL-4 response was also seen in cells with a naïve-like phenotype in response to CFP10.This difference was not seen on polyclonal activation with SEB. This might possibly suggest an antigen experienced early stage IL-4 producing cell within the naïve-like compartment. Alternatively, this might suggest a change in the transcriptional program within early stage precursor cells in a STAT6-independent manner due to consistently high levels of IL-4 that are produced by different cell types in chronic helminth infections (43, 44). The mechanisms by which these cells upregulate IL-4 production on antigen stimulation remains ill-defined as it appears that T-bet suppression rather than GATA-3 overexpression might be the mechanism of increased production of Th2 like cytokines in chronic filarial infections (45).

Finally, we noted that the increased IL-4 production in response to CFP10 in the naïve-like and TCM compartments was attenuated in the Inf subjects who were QuantiFERON TB gold positive. Presumably, such patients with LTBI have CD4+IFN-γ producing memory populations recognizing immunodominant Mtb-specific antigens possibly due to a state of periodic Th1-like antigenic stimulation (46). These results are consistent with the emerging hypothesis of CD4+ T cell plasticity where a pro-inflammatory environment and ongoing antigen-specific stimulation can alter the cytokine producing potential of Th2 cells, a concept that has been elegantly shown in a LCMV infection model (47). This plasticity may be related in part to histone modifications of specific T-bet gene loci in non-Th1 cells that, under appropriate conditions, can be permissive or suppressive and enable these cells to switch phenotype (48).

By combining phenotypic characterization with functional cytokine responses our study demonstrates, how chronic persistent filarial infection might modulate compartment –specific memory responses to parasite as well as Mtb-specific antigens in filarial-individuals. These findings may have significant implications in rational vaccine design for TB in endemic areas of the world where there is significant geographic overlap with helminth infections as well as open the way to a broader understanding of the memory response in latent TB. Further understanding of Th1 and Th2 specific CD4+ memory populations in chronic infections and their regulatory pathways for generation and maintenance should lead to better strategies to control these infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the subjects that participated in this study along with Margaret Beddall at the ImmunoTechnology Section, Vaccine Research Center (VRC) for her help with instruments, reagents and flow cytometry .

Because all the authors are government employees and this is a government work, the work is in the public domain in the United States. Notwithstanding any other agreements, the NIH reserves the right to provide the work to PubMedCentral for display and use by the public, and PubMedCentral may tag or modify the work consistent with its customary practices. You can establish rights outside of the U.S. subject to a government use license.

This research was supported [in part] by the Division of Intramural Research Program of the NIH,NIAID

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nutman TB, Kumaraswami V. Regulation of the immune response in lymphatic filariasis: perspectives on acute and chronic infection with Wuchereria bancrofti in South India. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:389–399. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anuradha R, George PJ, Hanna LE, Chandrasekaran V, Kumaran P, Nutman TB, Babu S. IL-4-, TGF-beta-, and IL-1-dependent expansion of parasite antigen-specific Th9 cells is associated with clinical pathology in human lymphatic filariasis. J Immunol. 2013;191:2466–2473. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kullberg MC, Pearce EJ, Hieny SE, Sher A, Berzofsky JA. Infection with Schistosoma mansoni alters Th1/Th2 cytokine responses to a non-parasite antigen. J Immunol. 1992;148:3264–3270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nookala S, Srinivasan S, Kaliraj P, Narayanan RB, Nutman TB. Impairment of tetanus-specific cellular and humoral responses following tetanus vaccination in human lymphatic filariasis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2598–2604. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2598-2604.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Global tuberculosis report 2013. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fifteen year follow up of trial of BCG vaccines in south India for tuberculosis prevention. Tuberculosis Research Centre (ICMR), Chennai. Indian J Med Res. 1999;110:56–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steel C, Lujan-Trangay A, Gonzalez-Peralta C, Zea-Flores G, Nutman TB. Immunologic responses to repeated ivermectin treatment in patients with onchocerciasis. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:581–587. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart GR, Boussinesq M, Coulson T, Elson L, Nutman T, Bradley JE. Onchocerciasis modulates the immune response to mycobacterial antigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:517–523. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitworth HS, Scott M, Connell DW, Donges B, Lalvani A. IGRAs--the gateway to T cell based TB diagnosis. Methods (San Diego, Calif.) 2013;61:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okoye A, Meier-Schellersheim M, Brenchley JM, Hagen SI, Walker JM, Rohankhedkar M, Lum R, Edgar JB, Planer SL, Legasse A, Sylwester AW, Piatak M, Jr., Lifson JD, Maino VC, Sodora DL, Douek DC, Axthelm MK, Grossman Z, Picker LJ. Progressive CD4+ central memory T cell decline results in CD4+ effector memory insufficiency and overt disease in chronic SIV infection. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2171–2185. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercier F, Boulassel MR, Yassine-Diab B, Tremblay C, Bernard NF, Sekaly RP, Routy JP. Persistent human immunodeficiency virus-1 antigenaemia affects the expression of interleukin-7Ralpha on central and effector memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152:72–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steel C, Nutman TB. Altered T cell memory and effector cell development in chronic lymphatic filarial infection that is independent of persistent parasite antigen. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McPherson T, Nutman TB. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. ASM press; 2007. Filarial nematodes. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lal RB, Ottesen EA. Enhanced diagnostic specificity in human filariasis by IgG4 antibody assessment. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:1034–1037. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.5.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lugli E, Goldman CK, Perera LP, Smedley J, Pung R, Yovandich JL, Creekmore SP, Waldmann TA, Roederer M. Transient and persistent effects of IL-15 on lymphocyte homeostasis in nonhuman primates. Blood. 2010;116:3238–3248. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkelman FD, Pearce EJ, Urban JF, Jr., Sher A. Regulation and biological function of helminth-induced cytokine responses. Immunol Today. 1991;12:A62–66. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(05)80018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearce EJ, Sun J, McKee AS, Cervi L. Th2 response polarization during infection with the helminth parasite Schistosoma mansoni. Immunol Rev. 2004;201:117–126. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00187.x. M. K. C. J. T. J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahanty S, King CL, Kumaraswami V, Regunathan J, Maya A, Jayaraman K, Abrams JS, Ottesen EA, Nutman TB. IL-4- and IL-5-secreting lymphocyte populations are preferentially stimulated by parasite-derived antigens in human tissue invasive nematode infections. J Immunol. 1993;151:3704–3711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elson LH, Calvopiña MH, Wilson YP, Araujo EN, Bradley JE, Guderian RH, Nutman TB. Immunity to Onchocerciasis: Putative Immune Persons Produce a Th1-like Response to Onchocerca volvulus. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1995;171:652–658. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearlman E, Kazura JW, Hazlett FE, Jr., Boom WH. Modulation of murine cytokine responses to mycobacterial antigens by helminth-induced T helper 2 cell responses. J Immunol. 1993;151:4857–4864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akue JP, Devaney E. Transmission intensity affects both antigen-specific and nonspecific T-cell proliferative responses in Loa loa infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:1475–1480. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1475-1480.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sartono E, Kruize YC, Kurniawan A, Maizels RM, Yazdanbakhsh M. In Th2-biased lymphatic filarial patients, responses to purified protein derivative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis remain Th1. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:501–504. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez-Pando R, Orozcoe H, Sampieri A, Pavon L, Velasquillo C, Larriva-Sahd J, M. Alcocer J, Madrid MV. Correlation between the kinetics of Th1, Th2 cells and pathology in a murine model of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. Immunology. 1996;89:26–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung YJ, LaCourse R, Ryan L, North RJ. Evidence inconsistent with a negative influence of T helper 2 cells on protection afforded by a dominant T helper 1 response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis lung infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6436–6443. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6436-6443.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun YJ, Lim TK, Ong AK, Ho BC, Seah GT, Paton NI. Tuberculosis associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing and non-Beijing genotypes: a clinical and immunological comparison. BMC infectious diseases. 2006;6:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nolan A, Fajardo E, Huie ML, Condos R, Pooran A, Dawson R, Dheda K, Bateman E, Rom WN, Weiden MD. Increased production of IL-4 and IL-12p40 from bronchoalveolar lavage cells are biomarkers of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the sputum. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez-Pando R, Orozco H, Arriaga K, Pavon L, Rook G. Treatment with BB-94, a broad spectrum inhibitor of zinc-dependent metalloproteinases, causes deviation of the cytokine profile towards type-2 in experimental pulmonary tuberculosis in Balb/c mice. International journal of experimental pathology. 2000;81:199–209. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2000.00152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowrie DB. DNA vaccines against tuberculosis. Current opinion in molecular therapeutics. 1999;1:30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merkenschlager M, Terry L, Edwards R, Beverley PC. Limiting dilution analysis of proliferative responses in human lymphocyte populations defined by the monoclonal antibody UCHL1: implications for differential CD45 expression in T cell memory formation. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1653–1661. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830181102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akbar AN, Terry L, Timms A, L. Beverley PC, Janossy G. Loss of Cd45r and Gain of Uchl1 Reactivity Is a Feature of Primed T-Cells. J Immunol. 1988;140:2171–2178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahnke YD, Brodie TM, Sallusto F, Roederer M, Lugli E. The who's who of T-cell differentiation: human memory T-cell subsets. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:2797–2809. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammarlund E, Lewis MW, Hansen SG, Strelow LI, Nelson JA, Sexton GJ, Hanifin JM, Slifka MK. Duration of antiviral immunity after smallpox vaccination. Nat Med. 2003;9:1131–1137. doi: 10.1038/nm917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chomont N, DaFonseca S, Vandergeeten C, Ancuta P, Sekaly RP. Maintenance of CD4+ T-cell memory and HIV persistence: keeping memory, keeping HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:30–36. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283413775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seder RA, Darrah PA, Roederer M. T-cell quality in memory and protection: implications for vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:247–258. doi: 10.1038/nri2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tapaninen P, Korhonen A, Pusa L, Seppälä I, Tuuminen T. Effector memory T-cells dominate immune responses in tuberculosis treatment: Antigen or bacteria persistence? International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2010;14:347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adekambi T, Ibegbu CC, Kalokhe AS, Yu T, Ray SM, Rengarajan J. Distinct effector memory CD4+ T cell signatures in latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, BCG vaccination and clinically resolved tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kipnis A, Irwin S, Izzo AA, Basaraba RJ, Orme IM. Memory T lymphocytes generated by Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination reside within a CD4 CD44lo CD62 ligand(hi) population. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7759–7764. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7759-7764.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lugli E, Dominguez MH, Gattinoni L, Chattopadhyay PK, Bolton DL, Song K, Klatt NR, Brenchley JM, Vaccari M, Gostick E, Price DA, Waldmann TA, Restifo NP, Franchini G, Roederer M. Superior T memory stem cell persistence supports long-lived T cell memory. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:594–599. doi: 10.1172/JCI66327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szabo SJ, Jacobson NG, Dighe AS, Gubler U, Murphy KM. Developmental commitment to the Th2 lineage by extinction of IL-12 signaling. Immunity. 1995;2:665–675. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adeeku E, Gudapati P, Mendez-Fernandez Y, Van Kaer L, Boothby M. Flexibility accompanies commitment of memory CD4 lymphocytes derived from IL-4 locus-activated precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9307–9312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704807105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohrs K, Harris DP, Lund FE, Mohrs M. Systemic dissemination and persistence of Th2 and type 2 cells in response to infection with a strictly enteric nematode parasite. J Immunol. 2005;175:5306–5313. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaph C, Rook KA, Goldschmidt M, Mohrs M, Scott P, Artis D. Persistence and function of central and effector memory CD4+ T cells following infection with a gastrointestinal helminth. J Immunol. 2006;177:511–518. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan JS, Canaday DH, Boom WH, Balaji KN, Schwander SK, Rich EA. Human alveolar T lymphocyte responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens: role for CD4+ and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and relative resistance of alveolar macrophages to lysis. J Immunol. 1997;159:290–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Panhuys N, Tang SC, Prout M, Camberis M, Scarlett D, Roberts J, Hu-Li J, Paul WE, Le Gros G. In vivo studies fail to reveal a role for IL-4 or STAT6 signaling in Th2 lymphocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12423–12428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806372105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Babu S, Kumaraswami V, Nutman TB. Transcriptional control of impaired Th1 responses in patent lymphatic filariasis by T-box expressed in T cells and suppressor of cytokine signaling genes. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3394–3401. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3394-3401.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chatterjee S, Kolappan C, Subramani R, Gopi PG, Chandrasekaran V, Fay MP, Babu S, Kumaraswami V, Nutman TB. Incidence of active pulmonary tuberculosis in patients with coincident filarial and/or intestinal helminth infections followed longitudinally in South India. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hegazy AN, Peine M, Helmstetter C, Panse I, Frohlich A, Bergthaler A, Flatz L, Pinschewer DD, Radbruch A, Lohning M. Interferons direct Th2 cell reprogramming to generate a stable GATA-3(+)T-bet(+) cell subset with combined Th2 and Th1 cell functions. Immunity. 2010;32:116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei G, Zhu L. Wei, J., Zang C, Hu-Li J, Yao Z, Cui K, Kanno Y, Roh TY, Watford WT, Schones DE, Peng W, Sun HW, Paul WE, O'Shea JJ, Zhao K. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.