Abstract

Phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase (PI3K) regulates a number of developmental and physiologic processes in skeletal muscle; however, the contributions of individual PI3K p110 catalytic subunits to these processes are not well-defined. To address this question, we investigated the role of the 110-kDa PI3K catalytic subunit β (p110β) in myogenesis and metabolism. In C2C12 cells, pharmacological inhibition of p110β delayed differentiation. We next generated mice with conditional deletion of p110β in skeletal muscle (p110β muscle knockout [p110β-mKO] mice). While young p110β-mKO mice possessed a lower quadriceps mass and exhibited less strength than control littermates, no differences in muscle mass or strength were observed between genotypes in old mice. However, old p110β-mKO mice were less glucose tolerant than old control mice. Overexpression of p110β accelerated differentiation in C2C12 cells and primary human myoblasts through an Akt-dependent mechanism, while expression of kinase-inactive p110β had the opposite effect. p110β overexpression was unable to promote myoblast differentiation under conditions of p110α inhibition, but expression of p110α was able to promote differentiation under conditions of p110β inhibition. These findings reveal a role for p110β during myogenesis and demonstrate that long-term reduction of skeletal muscle p110β impairs whole-body glucose tolerance without affecting skeletal muscle size or strength in old mice.

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle development and regeneration are finely tuned processes that require input from a number of physiologic, genetic, and biochemical stimuli (1). During development and regeneration, quiescent myogenic stem cells, known as satellite cells, are activated and enter the cell cycle (2–4). Once activated, satellite cells become replication competent, begin to express skeletal muscle-specific transcription factors, and proliferate (5, 6). These cells—now termed myoblasts—may proliferate further or may exit the cell cycle and become quiescent myogenic reserve cells, thus replenishing the satellite cell pool (7, 8). Myoblasts may fuse with existing, damaged fibers or may generate new myofibers through a process that includes cell cycle withdrawal, myoblast fusion, elongation, and hypertrophy of the syncytial myotube (9, 10). Clearly, identifying the molecular factors that influence these processes is essential to establish treatments to promote recovery following injury or during muscle-wasting disease states.

While much has been elucidated vis-à-vis biochemical modulators of skeletal muscle formation in general, the underlying molecular mechanisms that regulate the myoblast-to-myofiber transition are incompletely defined. One molecular mediator of skeletal muscle development is the lipid and protein kinase phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase (PI3K) (11–13). Class IA PI3K enzymes are composed of an 85-kDa regulatory subunit (p85) and a 110-kDa catalytic subunit (p110). The p110 catalytic subunit catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate to phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3], thus allowing PI(3,4,5)P3-dependent signal transduction (14). Three class IA p110 catalytic subunits have been identified (p110α, p110β, and p110δ), and of these, p110α and p110β are expressed in all tissues, including skeletal muscle (15). The role of p110α in receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)-mediated signal transduction, cell division, and cancer is well established (16–18), and roles for p110β in G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling, metabolism, and DNA replication have been reported (19–22).

The use of small-molecule inhibitors, small interfering RNA (siRNA), and genetic knock-in in mice has revealed that p110α mediates insulin and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) signal transduction in skeletal muscle (23–25) and contributes to myoblast differentiation and maintenance of muscle mass (23, 26). However, much less is known concerning the function of p110β in skeletal muscle, in particular, its role in muscle development. While previous research has shown that siRNA-mediated knockdown of p110β results in enhanced myoblast differentiation of C2C12 cells, p110β knockdown also results in the compensatory activation of p110α and Akt (26), thereby complicating interpretation regarding the precise role of p110β in myoblast differentiation.

Given the paucity of data regarding the role of p110β in skeletal muscle, we initiated cell- and animal-based experiments using pharmacological inhibitors, genetic manipulations, and in vivo conditional knockout of p110β. We report that inhibition of p110β catalytic activity delays the differentiation of cultured C2C12 cells and primary human skeletal myoblasts, whereas overexpression of p110β accelerates differentiation. Genetic ablation of p110β in skeletal muscle reduced muscle size and strength in young, but not old, mice and was associated with impaired glucose tolerance in old mice. During myoblast differentiation, overexpression of p110β was unable to compensate for the loss of p110α activity, but overexpression of p110α was able to compensate for the loss of p110β activity under a variety of conditions. Overall, our data reveal a role for p110β in early skeletal myoblast differentiation and in metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and reagents.

C2C12 cells, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), horse serum (HS), and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA). Penicillin-streptomycin, trypsin, Lipofectamine 2000, Opti-Mem medium, primary human skeletal myoblasts (catalog number A11440), and low-glucose DMEM (catalog number 11885-084) were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). TGX-221 and MK2206 were from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX). PI3K alpha inhibitor 2 (catalog number B-0304; PI3K alpha inhibitor 2 corresponds to Fig. 15e in reference 27 and is referred to here as p110αi) was purchased from Echelon Biosciences (Salt Lake City, UT). The monoclonal antibody against myosin heavy chain (MyHC; catalog number MF20) developed by D. Fischman and antibody against myosin heavy chain IIb (catalog number BF-F3-C) were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of NICHD and maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA. Antibodies for p-Akt Ser 473 (catalog number 4060), total (pan) Akt (catalog number 4685), phosphorylated glycogen synthase kinase 3β (p-GSK3β) Ser 9 (catalog number 9322), total GSK3β (catalog number 9315), p-PRAS40 Thr 246 (catalog number 2997), total PRAS40 (catalog number 2691), p110α (catalog number 4249), p110β (catalog number 3011), Akt1 (antibody C73H10; catalog number 2938), MEF2C (antibody D80C1; catalog number 5030), PI3K p85 (antibody 19H8; catalog number 4257), GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; catalog number 2118), and α-tubulin (11H10; catalog number 2125) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA). Mouse monoclonal anti-slow myosin antibody (clone NOQ7.5.4D, p/n M8421; the antibody detects the Myh7 gene product) and mouse monoclonal anti-fast myosin antibody (clone MY-32, p/n M4276; the antibody detects the Myh1 and Myh2 gene products) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The antibodies for myogenin (antibody 5FD) and MyoD (antibody 5.8A) and horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell culture conditions and siRNA.

C2C12 cells were grown and maintained in high-glucose DMEM with 10% FBS (growth medium [GM]) and antibiotics at 37°C in 5% CO2. All experiments were performed on cells between the third and fifth passages following receipt from the vendor (ATCC). To induce differentiation, the medium was switched from GM to high-glucose DMEM with 2% (vol/vol) horse serum (differentiation medium [DM]) at ∼90% myoblast confluence. For experiments using pharmacological inhibitors, medium was replaced daily with fresh medium containing inhibitor or an equivalent volume of vehicle (0.01% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]). Primary human skeletal myoblasts were seeded at a density of ∼9.3 × 105 cells/cm2 in low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 2% (vol/vol) HS and allowed to differentiate for periods of up to 72 h. Medium was replaced daily. For cell counting, medium was removed from the plates and monolayers were detached with 0.25% trypsin–EDTA. Cells were suspended in medium and counted in a hemacytometer chamber.

siRNA directed against Pik3ca (p110α; catalog number s71604) and nontargeting control siRNA (catalog number 4390843) were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). For transfections, C2C12 cells were reverse transfected at an initial seeding density of 2.75 × 104 cells/cm2 using Lipofectamine 2000 at a final concentration of 0.2%, as described previously (28).

Baculoviruses and transductions.

For delivery and expression of genes in cultured cells, we utilized the BacMam technology, in which nonreplicating baculoviruses have been modified by insertion of a mammalian expression cassette (Life Technologies). Open reading frame (ORF) clones encoding human p110α (PIK3CA; catalog number IOH3620), human p110β (PIK3CB; catalog number IOH82136), and human Akt1 (AKT1; catalog number IOH2692) in the pENTR221 vector were purchased from Life Technologies. The PIK3CA H1047R, PIK3CA D933A, and PIK3CB K805R point mutations were introduced by standard PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis, and an emerald green fluorescent protein (GFP) tag was fused to the wild-type and the K805R PIK3CB constructs at the amino terminus. An N-terminal src-myristoylation sequence tag was added to AKT1 using three sequential PCRs, and the PCR amplicon was then subcloned into pENTR221. Sequence-verified clones were subcloned into a pDEST8-CMV-n-GFP vector as described previously (29). These expression constructs were transformed into DH10BAC bacterial cells to generate and isolate bacmid DNA. This PCR-qualified bacmid DNA was transfected into SF9 insect cells for BacMam virus production according to the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system manual (30, 31) (Life Technologies).

Viral transductions were performed at the time of seeding using 10% (vol/vol) virus in antibiotic-free medium with 0.02% enhancer solution (catalog number PV5835; Life Technologies). Medium was replaced at 8 h following transduction for C2C12 cells and 24 h following transduction for primary human myoblasts.

Immunocytochemistry, microscopy, and image analysis.

Cells on coverslips were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by fixation in 3.7% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min. The coverslips were then washed three times in PBS and then permeabilized at room temperature for 30 min in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The coverslips were then blocked at room temperature for 60 min in blocking buffer (5% normal goat serum in PBS), followed by addition of primary antibody (1:250 for both myogenin and MyHC) diluted in antibody dilution buffer (1% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS), and incubated overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed three times in PBS, followed by incubation in the appropriate secondary antibody [anti-mouse IgG (H+L) F(ab′)2 fragment (Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate) or anti-mouse IgG (H+L) F(ab′)2 fragment (Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate); catalog numbers 4409 and number 4408, respectively; Cell Signaling Technologies] at a concentration of 1:2,000 for 60 min. Coverslips were washed three times and mounted using Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; catalog number 8961; Cell Signaling Technologies). For Fig. 2 and 5, images were captured using a Nikon TI-U inverted microscope equipped with a Retiga 2000R camera and NIS-Elements image analysis software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). For Fig. 6 and 8, images were captured using a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope and Zen analysis software. Results are presented as means ± standard errors from three independent experiments, with each experimental point derived from five randomly captured fields for each treatment group. To determine the percentage of myogenin-positive nuclei, the number of myogenin-positive nuclei was divided by the total number of nuclei in each microscopic field. The myotube fusion index was determined by counting the nuclei in every myotube (defined as MyHC-positive cells containing a minimum of two nuclei) per field and dividing by the total number of nuclei in the field. Myotube width was determined by measuring the five widest myotubes in each microscopic field at three separate points on each myotube, and myotube length was measured by determining the length of the five longest myotubes per field. Myotube area was determined by measuring the percentage of MyHC-positive staining per microscopic field using NIH ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

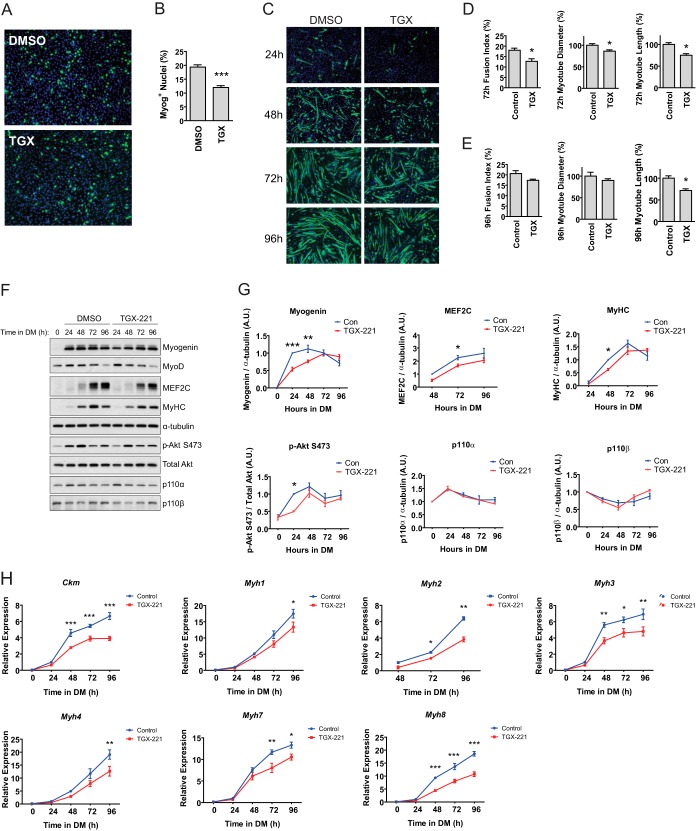

FIG 2.

Pharmacological blockade of p110β delays C2C12 myoblast differentiation. (A) Ninety percent confluent C2C12 myoblasts were treated with 0.01% DMSO or 1 μM TGX-221 (TGX) in DM for 24 h. Cells were then fixed and stained for myogenin (green) and DAPI (blue). Data represent those from three independent experiments. Magnification, ×40. (B) Quantification of myogenin-positive (Myog+) nuclei from the experiment whose results are shown in panel A (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; 5 fields were analyzed per experimental point; ***, P < 0.001). (C) Ninety percent confluent myoblasts were treated as described in the legend to panel A and allowed to differentiate for the indicated times before fixation and staining with MyHC (green) and DAPI (blue). Magnification, ×40. (D and E) Fusion index, diameter, and length of myotubes from panel C after 72 h (D) or 96 h (E) in DM (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; 5 fields were analyzed per experimental point; *, P < 0.05). (F) Ninety percent confluent proliferating myoblasts were harvested either immediately before (0 h) or at 24-h intervals following treatment with 0.01% DMSO or 1 μM TGX-221 in DM. Western blotting was performed using the antibodies indicated on the right. (G) Quantification of Western blots from panel F normalized to the amount of α-tubulin or total Akt (for p-Akt) (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments per time point; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). A.U., arbitrary units;. (H) Approximately 90% confluent C2C12 myoblasts wereallowed to differentiate for the indicated times before RNA extraction. Real-time PCR was performed using the indicated primers/probes, and the levels of expression were normalized to the level of B2m expression (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments per time point; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

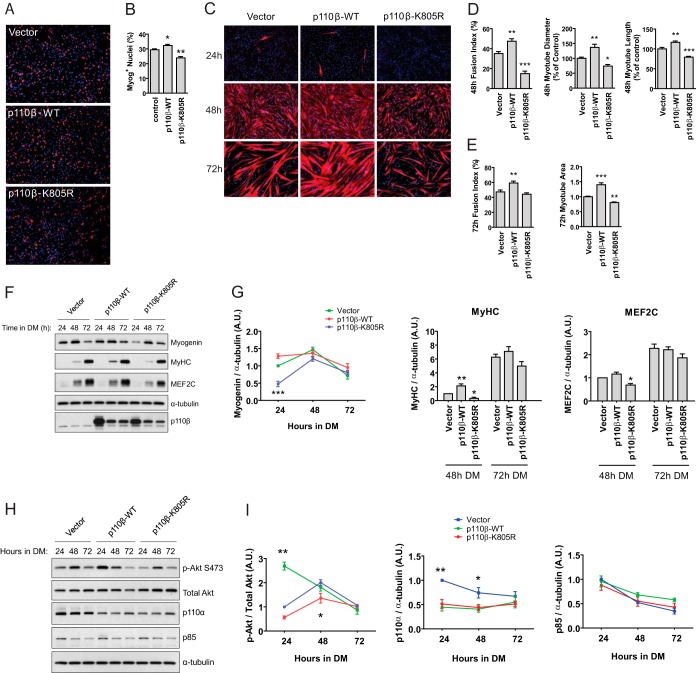

FIG 5.

Overexpression of p110β promotes myogenesis in primary human skeletal myoblasts. (A) Primary human skeletal myoblasts were transduced with the control vector (Vector), wild-type p110β (p110β-WT), or kinase-inactive p110β (p110β-K805R) as described in Materials and Methods. At 24 h following transduction, cells were fixed and stained for myogenin (red) and DAPI (blue). (B) Quantification of myogenin-positive nuclei derived from the experiments whose results are shown in panel A (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; 5 fields were analyzed per experimental point; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (C) Human skeletal myoblasts were transduced with the indicated constructs and allowed to differentiate for the indicated times before fixation and staining with MyHC (red) and DAPI (blue). Magnification, ×40. (D) Quantification of myotube fusion index, diameter, and length from experiments whose results are shown in panel C after 48 h (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; 5 fields were analyzed per experimental point; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). (E) Quantification of myotube fusion index and area from experiments whose results are shown in panel C after 72 h of differentiation (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; 5 fields were analyzed per experimental point; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). (F) Immunoblots for myogenin, MyHC, MEF2C, α-tubulin, and p110β in primary human skeletal myoblasts after 24, 48, or 72 h in DM. (G) Quantification of the blots shown in panel F normalized to the amount of α-tubulin (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). (H) Immunoblots, following 24, 48, or 72 h in DM, for p-Akt S473, total Akt, p110α, p85, and α-tubulin in primary human skeletal myoblasts transduced with the indicated constructs. (I) Quantification of the blots shown in panel H normalized to the amount of total Akt or α-tubulin, as indicated (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

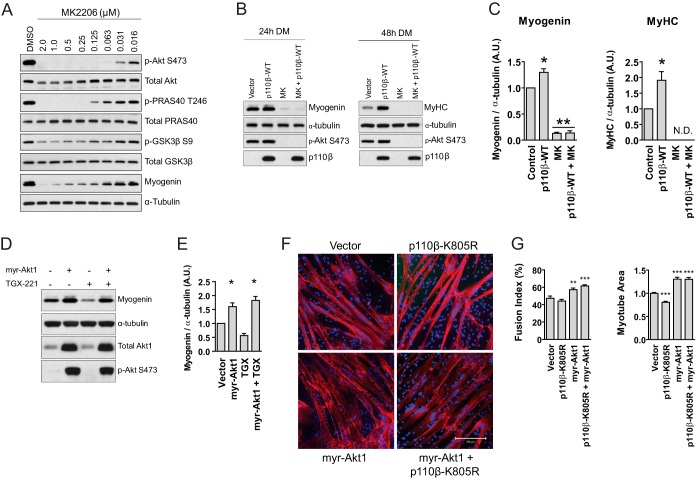

FIG 6.

Akt regulates p110β-mediated myoblast differentiation. (A) Ninety percent confluent C2C12 myoblasts were treated with the indicated concentrations of MK2206 or DMSO vehicle (0.01%) in DM and allowed to differentiate for 24 h, followed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. (B) Immunoblotting assays were performed on lysates derived from differentiating C2C12 cells expressing the vector control, p110β-WT, or 250 nM MK2206 for 24 or 48 h, as indicated, using the noted antibodies. All treatments received equal quantities of virus or solvent; i.e., cells not exposed to MK2206 (MK) received an equivalent volume of DMSO vehicle, and cells not transduced with p110β-WT were transduced with the vector control. (C) Quantification of the myogenin and MyHC blots shown in panel B normalized to the amount of α-tubulin (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments per time point; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; N.D., not detected). (D) C2C12 cells were seeded and transduced with the vector control or myristoylated Akt1 (myr-Akt1) in GM. At 24 h following transduction, GM was switched to DM containing 1 μM TGX-221 or DMSO vehicle, and cells were allowed to differentiate for 24 h. Representative immunoblots for myogenin, α-tubulin, total Akt1, and p-Akt S473 are shown. (E) Quantification of the myogenin blots shown in panel D normalized to the amount of α-tubulin (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; *, P < 0.05). (F) Immunocytochemistry of primary human skeletal myoblasts expressing the indicated constructs after 72 h in DM for MyHC (red) and DAPI nuclear stain (blue). Bar = 200 μm. (G) Quantification of fusion index and myotube area for myoblasts from the experiments whose results are shown in panel F (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; 5 fields were analyzed per experimental point; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

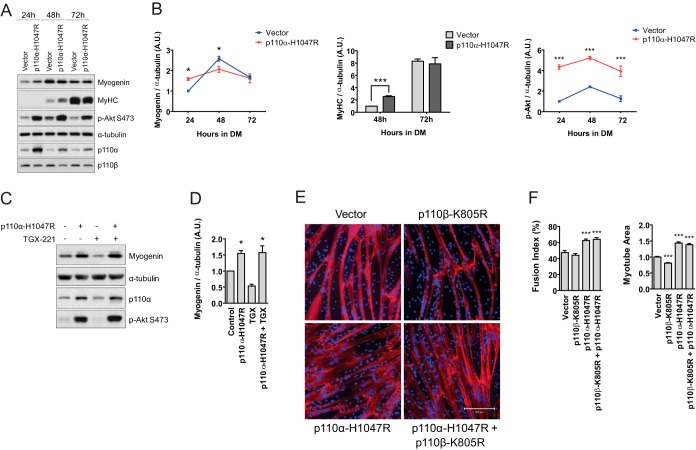

FIG 8.

p110α can compensate for p110β inhibition in myoblast differentiation. (A) Immunoblots, following 24, 48, or 72 h in DM, of primary human skeletal myoblasts transduced with either control vector or p110α-H1047R. (B) Quantification of the blots shown in panel A normalized to the amount of α-tubulin (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001). (C) C2C12 cells were seeded and transduced in GM with the vector control or p110α-H1047R as described in Materials and Methods. At 24 h following transduction, GM was switched to DM containing 1 μM TGX-221 or DMSO vehicle, and cells were allowed to differentiate for 24 h before harvest. Representative immunoblots for myogenin, α-tubulin, p110α, and p-Akt S473 from three independent experiments are shown. (D) Quantification of the myogenin blots shown in panel C normalized to the amount of α-tubulin (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; *, P < 0.05). (E) Immunocytochemistry of primary human skeletal myoblasts expressing the indicated constructs after 72 h in DM for MyHC (red) and DAPI nuclear stain (blue). Bar = 200 μm. (F) Fusion index and myotube area for myotubes from the experiments whose results are shown in panel E (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; 5 fields were analyzed per experimental point; ***, P < 0.001).

Animals.

All experimental procedures utilizing mice were conducted under the guidelines on the humane use and care of laboratory animals for research and in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee of the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine. C57BL/6J mice carrying LoxP sites flanking exon 2 of the Pik3cb gene have been described previously (21). These mice were crossed with mice expressing the Cre recombinase from the Myf5 locus (32) (stock number 007893; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to generate Myf5-Cre/Pik3cbflox/flox offspring lacking p110β in skeletal muscle (referred to as here p110β muscle-knockout [p110β-mKO] mice). Pik3cbflox/flox mice lacking the Cre allele (referred to here as p110β-flox mice) were used as controls. Genotyping for detection of floxed Pik3cb was performed as described previously (21), and genotyping for detection of Cre was performed as described by The Jackson Laboratory for mouse stock number 007893. Mice were housed on a 12-h light and 12-h dark cycle and provided standard chow and water ad libitum.

Metabolic cages and determination of lean mass.

Comprehensive lab animal monitoring system (CLAMS; Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) metabolic cage studies were performed over a 48-h period (2 light cycles and 2 dark cycles) to determine the respiratory exchange ratio (RER), food intake, and activity for mice 8 to 9 weeks of age. The rate of O2 consumption (VO2; ml/kg of body weight/h), the rate of CO2 consumption (VCO2; ml/kg/h), RER, and food intake (g) were measured at 34-min intervals. RER was calculated as the rate of CO2 production divided by the rate of O2 consumption (VCO2/VO2). Activity was determined by infrared beam breaks in the x, y, and z axes. Body fat and lean mass were determined by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA).

Determination of grip strength.

A grip strength meter (Columbus Instruments) was used to measure grip strength as an indicator of neuromuscular strength and function. The grip strength meter was positioned horizontally, and mice were held by the tail and lowered toward the apparatus. The mice were allowed to grasp the pull bar and were then pulled backward in the horizontal plane. The force applied to the bar at the moment that the grasp was released was recorded as the peak tension (kg). The test was repeated 5 consecutive times within the same session, and the highest value from the 5 trials was recorded as the grip strength for that animal. Peak tension was expressed relative to body mass.

Histology.

Formalin-fixed quadriceps muscles from p110β-flox and p110β-mKO mice were used for processing and preparation of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)- and reticulin-stained slides. Image analysis was performed following digital scanning of the reticulin-stained sections. CellProfiler cell image analysis software (www.cellprofiler.org) was used to apply a series of intensity and morphometric filters to identify and measure fiber cross sections within the regions of interest. The measurements were used to calculate the distribution and average of the cross-sectional areas of myofibers from each group.

Glucose and insulin tolerance.

For the glucose tolerance test (GTT), 8-week-old or 20.5-month-old mice were fasted overnight prior to intraperitoneal injection of 2 g/kg dextrose. Blood samples were obtained at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after dextrose administration, and the blood glucose concentration was measured by use of a glucometer. Insulin tolerance tests were performed on 10-week-old or 21-month-old mice fasted for 5 h by intraperitoneal injection of 1 U/kg insulin (Sigma), followed by blood glucose concentration determination at 0, 15, 30, and 60 min.

Treadmill exercise.

Mice were acclimated to the treadmill on the day of the treadmill test. Mice were placed on a nonmoving treadmill (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) for 10 min for acclimation, followed by a warm-up procedure where the mice were allowed to walk on the treadmill for 5 min with the belt running at 7 m/min. The speed was then ramped up with increases of 4 m/min every 4 min. During the experiment, a shock plate at the back of treadmill was set at 1.5 mA to provide a stimulus for the animals to run. The experiment was concluded when a mouse displayed signs of exhaustion, which included spending greater than 5 consecutive seconds on the shock grid without attempting to reengage the treadmill or was unwilling to return to the treadmill. Total running time, distance, and running speed were recorded for each mouse.

In vivo insulin signaling.

Following an overnight fast, the mice were anesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol in PBS (Avertin) and injected with 5 U of insulin (Sigma) or diluent (saline) via the inferior vena cava. Five minutes after the insulin bolus, the quadriceps muscles were removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Tissue harvest for RNA and protein.

Tissues were dissected from anesthetized mice, immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until extraction of RNA or protein.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real-time PCR.

RNA isolation from cells was performed as described previously (24) using the TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). For tissues, ∼20 mg tissue was homogenized in TRIzol reagent using a handheld manual disruptor, followed by RNA isolation according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized using a High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit with RNase inhibitor (catalog number 4374966; Life Technologies) and 2 μg RNA in a 40-μl final reaction volume according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was either used immediately or stored at −80°C until use. Real-time PCR was performed using 20 ng cDNA in a Stratagene MX 3000 thermal cycler with the parameters set as follows: 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. Measurements were taken in the exponential phase when fluorescence exceeded the threshold of detection above the background (threshold cycle [CT] values). For relative comparison of treatments or conditions, differences were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCT method with normalization to the level of B2m gene expression. Primers/probes for real-time PCR of the following genes were purchased from Applied Biosystems (catalog numbers are in parentheses): Ckm (Mm01321487_m1), Myh1 (Mm01332493_g1), Myh2 (Mm01332564_m1), Myh3 (Mm01332462_g1), Myh4 (Mm01332516_g1), Myh7 (Mm01319006_g1), Myh8 (Mm01329494_m1), and B2m (Mm00437762_m1).

Protein extraction and immunoblotting.

Extraction of protein from cells was performed as described previously (24). For tissues, ∼25 mg tissue was homogenized in 1× cell lysis buffer (catalog number 9803; Cell Signaling Technologies) plus protease inhibitors (Halt cocktail; Pierce Biotech, Rockford, IL) using a handheld manual disruptor. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (33). Western immunoblotting was performed as described previously (26), and densitometric analysis was performed using NIH ImageJ software.

Statistics.

Data are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (SEMs). Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or two-way ANOVA, as appropriate, and GraphPad Prism (version 5) software. The Tukey or Bonferroni multiple-range test was performed a posteriori for one-way or two-way ANOVA, respectively. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Pharmacological inhibition of PI3K p110β delays myoblast differentiation.

Previous research has shown that siRNA-mediated reductions in p110β were associated with increased C2C12 myoblast differentiation secondary to enhanced activation of the p110α/Akt pathway (26). To directly examine the role of p110β catalytic activity (while avoiding the compensatory activation of p110α that was observed in p110β-deficient C2C12 cells), we utilized the p110β-specific pharmacological inhibitor TGX-221 (34). TGX-221 has been shown to inhibit catalytic activation of p110β in C2C12 cells (35) but is not expected to reduce p110β protein abundance; thus, the role of p110β catalytic activity alone in differentiating myoblasts can be studied using this inhibitor.

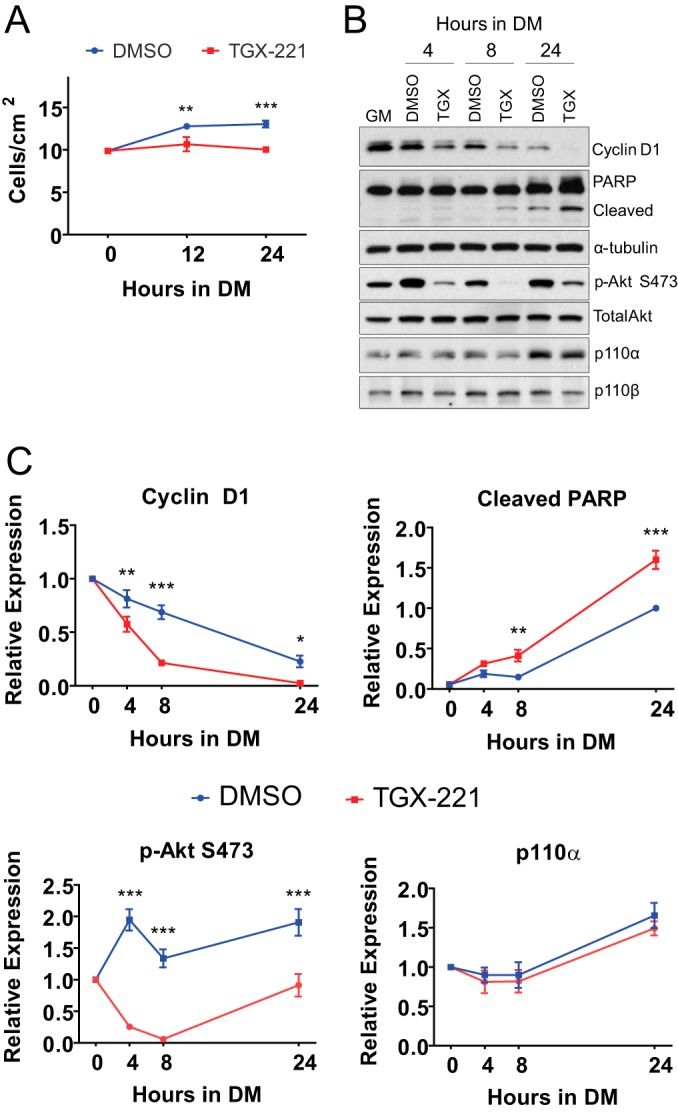

We first established whether treatment with TGX-221 altered myoblast proliferation during the first 24 h following the switch from growth medium (GM) to differentiation medium (DM). Following the switch to DM, control cells continued to proliferate, reaching 29% and 31% greater numbers of cells at 12 and 24 h, respectively (Fig. 1A). Conversely, myoblasts treated with TGX-221 did not continue to proliferate. To identify molecular mechanisms that may underlie this finding, we tested whether the levels of the cell cycle regulator cyclin D1 (a positive regulator of myoblast proliferation [36, 37]), cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP; indicative of apoptosis), phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), p110α, or p110β were altered during this period. Cells administered TGX-221 showed reduced levels of cyclin D1 and increased cleavage of PARP over time compared to control cells (Fig. 1B and C). Cells treated with TGX-221 also showed reduced Akt activation. p110α levels were elevated by ∼50% (P < 0.05) at 24 h following the onset of differentiation, but this increase was unaffected by TGX-221. No differences in the levels of p110β were observed across times or treatments. These data reveal that the reduced cell number in TGX-221-treated myoblasts during early differentiation is associated with biochemical indicators of cytostasis and increased apoptosis.

FIG 1.

Pharmacological inhibition of p110β inhibits cell proliferation during early differentiation. (A) Numbers of 90% confluent proliferating C2C12 myoblasts in GM harvested either immediately before (0 h) or at 12- or 24-h intervals following treatment with 0.01% DMSO or 1 μM TGX-221 in DM. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). (B) Myoblasts were treated as described in the legend to panel A and harvested following 4, 8, or 24 h of treatment. Western blotting was performed using the antibodies indicated on the right. Blots are representative of those from 3 or 4 independent experiments. (C) Quantification of Western blots from panel B first normalized to the amount of α-tubulin or total Akt (for p-Akt) and then to that of DMSO at 0 h (cyclin D1, p-Akt, p110α) or 24 h (cleaved PARP) (means ± SEMs; n = 3 or 4 independent experiments per time point; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

We next determined the effects of p110β inhibition on myotube formation over 96 h. Accordingly, ∼90% confluent C2C12 myoblasts were treated with TGX-221 or vehicle (DMSO) in DM and allowed to differentiate. Immunofluorescence analysis of fixed cells revealed that TGX-221-treated cells possessed ∼38% less myogenin-positive nuclei than control cells at 24 h after the onset of differentiation (Fig. 2A and B). Additionally, the fusion index of TGX-221-treated myotubes was decreased by ∼29%, the myotube length was decreased by ∼25%, and the myotube diameter was decreased by ∼14% compared to the values for control cells at 72 h following the onset of differentiation (Fig. 2C and D). At 96 h following the onset of differentiation, there were no differences in the fusion index (P < 0.07) or myotube diameter between control and TGX-221-treated cells; however, the myotube length was decreased by ∼28% (Fig. 2E).

To study the molecular mechanisms that potentially regulated these observations, we next examined the expression of proteins known to regulate myogenesis during the 96-h period of differentiation. Treatment of cells with TGX-221 reduced the level of expression of myogenin at 24 h and 48 h following the onset of differentiation compared to that for control cells (Fig. 2F and G). At 48 h following the onset of differentiation, TGX-221 administration was associated with reduced myosin heavy chain (MyHC) immunoreactivity, as determined by utilizing an antibody recognizing multiple MyHC species (38). Additionally, the expression of MEF2C was reduced at 48 and 72 h following the initiation of differentiation in cells treated with TGX-221. TGX-221 did not affect MyoD protein abundance at any time point examined (graph not shown). Akt phosphorylation was reduced at 24 h following differentiation in TGX-221-treated cells, whereas TGX-221 did not affect the p110α or p110β abundance compared to that for the control.

Muscle-specific transcription factors regulate expression of a number of RNA transcripts involved in myogenesis, including muscle creatine kinase (Ckm) and MyHC isoforms (39, 40); hence, we next asked whether p110β inhibition reduced expression of Ckm and the MyHC isoforms Myh1 (type IId/x), Myh2 (type IIa), Myh3 (embryonic), Myh4 (type IIb), Myh7 (Ia), and Myh8 (perinatal). At 48 h following the onset of differentiation, TGX-221-treated cells exhibited reductions in Ckm, Myh3, and Myh8 compared to their levels in vehicle-treated control cells (Fig. 2H). At 72 h following the onset of differentiation, TGX-221 treatment was associated with significant reductions in the levels of expression of Ckm, Myh2, Myh3, Myh7, and Myh8 compared to those for the control; and at 96 h following the onset of differentiation, TGX-221 treatment was associated with significant reductions in the levels of expression of Ckm, Myh1, Myh2, Myh3, Myh4, Myh7, and Myh8 compared to those for the vehicle-treated control cells. Collectively, data from Fig. 2 indicate that inhibition of p110β catalytic activity delays C2C12 myotube formation and differentiation.

Skeletal muscle-specific deletion of p110β reduces skeletal muscle mass and strength in young mice.

To determine the degree to which our findings in C2C12 cells were recapitulated in skeletal muscle in vivo, we generated male mice with a conditional deletion of the Pik3cb gene in skeletal muscle (p110β-mKO), as well as control mice (p110β-flox), using the Cre-Lox system driven by the Myf5 promoter. Mice were born in the expected Mendelian ratios with no apparent gross abnormalities.

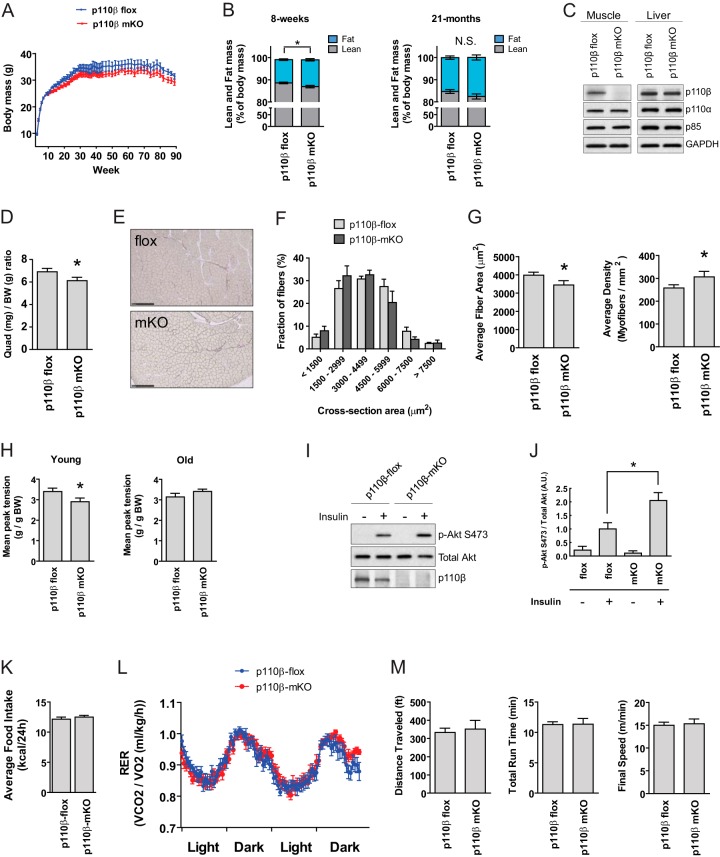

There were no differences in body weight between p110β-mKO and control mice up to 89 weeks of age (Fig. 3A). At 8 weeks of age, p110β-mKO mice possessed ∼15% greater body fat than control littermates (10.53 ± 0.38 versus 12.12 ± 0.50) and ∼2% less lean mass than control littermates (88.59 ± 0.34 versus 86.93 ± 0.53); however, no differences in body fat or lean mass were seen in 21-month-old mice (Fig. 3B). Western immunoblot analysis of quadriceps muscles revealed that p110β was virtually undetectable in p110β-mKO mice and that expression of p110α and p85 proteins did not differ between genotypes (Fig. 3C). Additionally, no differences in p110β, p110α, or p85 levels in liver were observed between p110β-flox and p110β-mKO mice, verifying the lineage specificity of the knockout (Fig. 3C). We next examined the morphological characteristics of the quadriceps muscles of p110β-mKO and control mice. Qualitative microscopic examination of H&E-stained muscle sections revealed no evidence of myofiber degeneration, regeneration, or necrosis (data not shown). While quadriceps muscle mass was reduced by ∼12% in young (age, 10 weeks) p110β-mKO mice compared to that in young control mice (Fig. 3D), no differences in muscle mass between genotypes were observed for the quadriceps, tibialis anterior (TA), or soleus muscle in old (age, 22 months) mice (not shown). Analysis of fiber cross-section area in young mice revealed a trend toward smaller fibers (Fig. 3E), a reduced mean cross-sectional area, and an increased myofiber density in the quadriceps of p110β-mKO mice compared to the values for the quadriceps of p110β-flox mice (Fig. 3G). No differences in any of these parameters were observed between genotypes in the quadriceps, TA, or soleus muscle in old mice (not shown). Further, we noted no differences in the levels of myosin heavy chain protein or RNA transcript expression in the muscles of old or young mice between genotypes (not shown), suggesting that fiber type shifts had not occurred at either age.

FIG 3.

Genetic ablation of p110β in skeletal muscle reduces muscle size and strength in young mice. (A) Body weights of 3- to 89-week-old mice (n = 9 to 14 per genotype). (B) Fat mass and lean mass of 8-week-old and 21-month-old male mice (means ± SEMs; n = 12 per genotype for 8-week-old mice and n = 8 per genotype for 21-month-old mice; *, P < 0.05; N.S., not significant). (C) Western blots of quadriceps muscle and liver lysates from p110β-flox and p110β-mKO mice. Blots are representative of those for 8 mice per genotype. (D) Quadriceps (Quad) muscle-to-body weight (BW) ratio of age-matched male mice (n = 8 per genotype; *, P < 0.05). (E) Representative cross-section of quadriceps muscle stained with reticulin. (F) Distribution of quadriceps muscle myocyte cross-sectional area for p110β-flox and p110β-mKO mice (means ± SEMs; n = 6 per genotype). (G) Average quadriceps muscle cross-sectional area and myofiber density from the data shown in panel F (means ± SEMs; n = 6 per genotype; *, P < 0.05). (H) Average peak tension from grip strength test normalized to body weight (means ± SEMs; n = 10 per genotype for young [age, ∼8 weeks] mice and n = 9 to 11 per genotype for old [age, ∼20 months] mice; *, P < 0.02). (I) Representative Western blots of quadriceps protein lysates prepared from p110β-flox and p110β-mKO mice treated with saline or insulin for 5 min through inferior vena cava injection. Blots are representative of those from 3 independent experiments. (J) Quantification of p-Akt S473 expression from data shown in panel I (means ± SEMs; n = 3 mice per treatment group; *, P < 0.05). (K) Average food intake over 24 h in 8- to 9-week-old young mice (n = 12 per genotype). (L) Average respiratory exchange ratio (RER; VCO2/VO2) of 8- to 9-week-old p110β-flox and p110β-mKO mice over a 48-h period in metabolic chambers (n = 12 per genotype). (M) Running time, total distance, and final speed during a forced exercise treadmill test in old (age, ∼21.5 months) mice (means ± SEMs; n = 9 per genotype).

In a grip strength test, the mean tension as a function of body mass exhibited by young p110β-mKO mice was ∼15% less than that exhibited by control mice. There was no difference in grip strength between genotypes in old mice (Fig. 3H).

Previous research has shown that Akt phosphorylation is enhanced in response to IGF-I in p110β-deficient C2C12 myoblasts compared to control myoblasts (24) and in response to insulin/epidermal growth factor (EGF) administration in mammary tumor-derived cells lacking p110β compared to p110β-sufficient cells (41). To determine whether this response also occurred in skeletal muscle in vivo, young mice were injected with insulin and the quadriceps muscle was analyzed for phosphorylation of Akt. We found that the muscles of p110β-mKO mice showed ∼2-fold greater Akt phosphorylation than those of p110β-flox mice in response to insulin (Fig. 3I and J), indicating that this phenomenon occurs in skeletal muscle in vivo.

We next tested whether the skeletal muscle-specific loss of p110β altered physical activity or substrate utilization. We observed no differences in food intake or the respiratory exchange ratio over a 48-h period between young p110β-mKO mice and young control mice (Fig. 3K and L). Likewise, there were no differences in O2 consumption, CO2 production, heat production, or ambulatory activity between genotypes over a 48-h period in young mice (not shown) and no difference in treadmill running performance between genotypes in old mice (Fig. 3M).

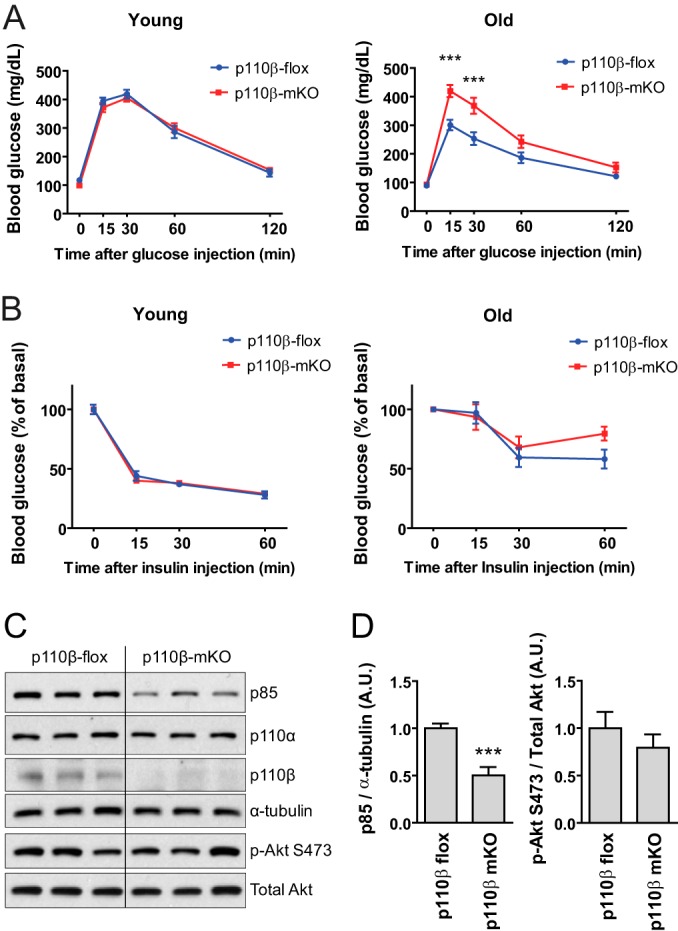

Loss of p110β in skeletal muscle impairs glucose tolerance in old mice.

We next asked whether the skeletal muscle-specific loss of p110β altered glucose tolerance or insulin sensitivity. We observed no differences in fasted blood glucose concentrations between young control and p110β-mKO mice and no differences in response to a glucose bolus challenge over a 120-min period between genotypes (Fig. 4A, left). Conversely, old p110β-mKO mice were less glucose tolerant than old control mice (Fig. 4A, right). There were no differences in blood glucose concentrations in response to the intraperitoneal injection of insulin between control mice and p110β-mKO mice, young or old, at time points up to 60 min following injection (Fig. 4B). To determine whether muscle-specific alterations in PI3K/Akt pathway components were associated with glucose intolerance in old p110β-mKO mice, we examined the quadriceps muscle. With the exception of reduced levels of p85, we noted no differences in PI3K/Akt signaling components (Fig. 4C and D). Together, these findings suggest that skeletal muscle p110β is not necessary for maintenance of insulin sensitivity, although the loss of p110β in skeletal muscle was associated with impaired whole-body glucose tolerance in old mice.

FIG 4.

Effects of skeletal muscle-specific loss of p110β on metabolism. (A) Following an overnight fast, 8-week-old (Young) or 20.5-month-old (Old) mice were administered 2 g/kg dextrose by intraperitoneal injection. The blood glucose level was determined at the indicated time points (means ± SEMs; n = 8 mice per genotype per age group). (B) Following a 5-h fast, 10-week-old (Young) or 21-month-old (Old) mice were administered 5 U insulin by intraperitoneal injection. Results represent the blood glucose concentration as a percentage of the starting value at the time of injection (time zero) (means ± SEMs; n = 8 mice per genotype per age group). (C) Western blots of lysates of quadriceps muscle from p110β-flox and p110β-mKO mice. (D) Quantification of the blots shown in panel C normalized to the amount of α-tubulin or total Akt, as indicated (means ± SEMs; n = 8 or 9 mice per genotype; ***, P < 0.001).

Overexpression of p110β promotes differentiation of primary human skeletal myoblasts.

Our observations from Fig. 2 showed that pharmacological inhibition of p110β in C2C12 cells delays myotube formation. We next tested whether forced expression of p110β would promote the opposite effect, i.e., accelerate skeletal muscle differentiation. Primary human skeletal myoblasts were transduced with empty vector or vector encoding wild-type p110β (p110β-WT). To control for potential noncatalytic effects of p110β, myoblasts were also transduced with a catalytically inactive form of p110β (p110β-K805R) (21). Figures 5A and B show that cells expressing p110β-WT possessed ∼10% more myogenin-positive nuclei than control cells transduced with the vector only; conversely, there were ∼19% fewer myogenin-positive nuclei in cells expressing p110β-K805R than control myoblasts. Next, we established the effect of overexpression of p110β-WT or p110β-K805R on human myotube formation. At 48 h following the onset of differentiation, p110β-WT-transduced cells possessed an ∼35% greater fusion index, an ∼17% greater myotube length, and an ∼37% greater myotube diameter than control cells (Fig. 5C and D). Following 72 h of differentiation, p110β-WT-transduced cells possessed an ∼25% greater fusion index and an ∼40% greater myotube area than control myotubes (Fig. 5C and E). Conversely, at 48 h following differentiation initiation, p110β-K805R-expressing cells showed an ∼57% decreased fusion index, an ∼21% decreased myotube length, and an ∼26% decreased myotube diameter than control myotubes, and at 72 h p110β-K805R-expressing cells showed an ∼19% reduced myotube area (Fig. 5C to E).

We next determined the effects of p110β overexpression on the abundances of muscle-specific transcription factors during the 72-h period of differentiation. There was a nominal, but not significant, increase in myogenin abundance at the 24-h time point in p110β-WT-expressing cells, and at 48 h, both MyHC and MEF2C levels were increased (Fig. 5F and G). Cells expressing p110β-K805R showed ∼50% less myogenin at 24 h and ∼70% less MyHC and ∼30% less MEF2C at 48 h. We detected no differences in myogenin, MyHC, or MEF2C levels at 72 h following any treatment. Together, these data demonstrate that overexpression of p110β accelerates human myoblast differentiation and myotube formation and that this effect is mediated by the kinase activity of the molecule.

Akt is a well-known mediator of myoblast differentiation in general (42–44); however, whether Akt activation was modified during p110β-stimulated myoblast differentiation was not known. To address this, primary human skeletal myoblasts were transduced with empty vector or vectors encoding wild-type p110β or kinase-dead p110β and harvested at time points up to 72 h following the onset of differentiation. Western blotting revealed that cells expressing p110β-WT had significantly greater Akt phosphorylation following 24 h of differentiation than control cells, while phosphorylation of Akt was significantly inhibited at 48 h in cells expressing p110β-K805R (Fig. 5H and I). Akt phosphorylation did not differ at 72 h across treatments. Additionally, the abundance of p110α, but not that of p85, was significantly reduced in cells expressing either p110β-WT or p110β-K805R at 24 and 48 h (Fig. 5H and I). These results reveal that Akt is activated in response to p110β overexpression during early human skeletal muscle cell differentiation, even under conditions of reduced p110α.

Akt is necessary for p110β-mediated myoblast differentiation.

Results from Fig. 5 showed that Akt is activated beyond control levels in response to p110β overexpression during early myoblast differentiation. To test whether Akt is essential for p110β-mediated myoblast differentiation, we first utilized the pharmacological inhibitor MK2206 in combination with p110β overexpression in differentiating C2C12 myoblasts. Dose-response experiments revealed that a concentration of 250 nM MK2206 was sufficient to inhibit phosphorylation of Akt and Akt substrates following 24 h of incubation in DM (Fig. 6A). Next, C2C12 cells transduced with p110β-WT or empty vector were treated with 250 nM MK2206 for 24 or 48 h and analyzed for expression of myogenin (24 h) or MyHC (48 h) (Fig. 6B). While p110β overexpression increased myogenin and MyHC levels at 24 and 48 h following the onset of differentiation, respectively, p110β overexpression was not able to overcome the Akt blockade for myogenin or MyHC at either time point (Fig. 6B and C). To further explore the relationship between p110β and Akt in differentiation, we next tested whether constitutive activation of Akt could overcome the pharmacological blockade of p110β catalytic activity, which delayed C2C12 cell differentiation (Fig. 2). We found that overexpression of myristoylated Akt1 increased the expression of myogenin at 24 h following the switch to DM and that this effect was not suppressed in the presence of TGX-221 (Fig. 6D and E). Finally, we tested whether overexpression of myristoylated Akt1 could prevent the reductions in primary human myotube formation induced by catalytically inactive p110β (Fig. 5). We observed that, indeed, expression of myristoylated Akt1 completely prevented the reductions in myotube area induced by kinase-dead p110β and also enhanced the fusion index and myotube area compared to those for control myotubes (Fig. 6F and G). Taken together, these data indicate that Akt is necessary for p110β-mediated myoblast differentiation.

p110β cannot compensate for p110α during myogenesis.

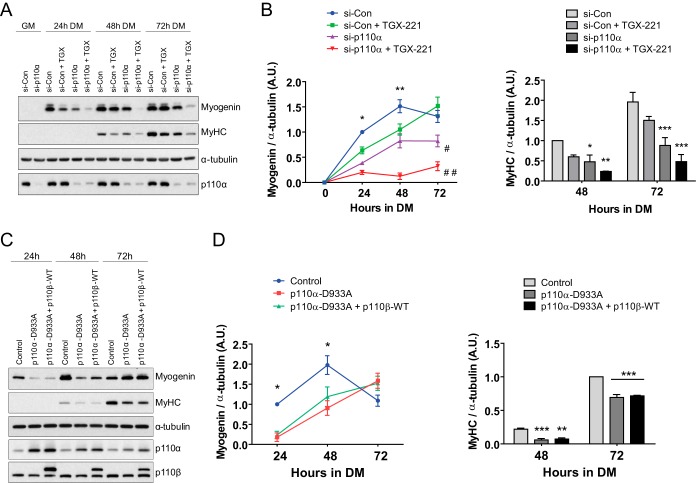

Previous research has shown that there exists a degree of functional redundancy between p110 isoforms in insulin signaling, cell proliferation, and cell survival in various cell types (45, 46). We therefore asked whether p110β was capable of compensating for p110α in skeletal myogenesis. We first examined the degree to which the reduction of p110α, alone and in combination with pharmacological inhibition of p110β, affected C2C12 myoblast differentiation. Accordingly, myoblasts were treated with siRNA directed against p110α and allowed to differentiate for periods of up to 72 h. Additionally, some p110α-deficient cells were treated with TGX-221 beginning at the onset of differentiation. We found that p110α-deficient cells expressed significantly less myogenin protein at 24, 48, and 72 h following the onset of differentiation than cells treated with negative-control siRNA (Fig. 7A and B). Likewise, the level of the MyHC protein was significantly reduced in p110α-deficient cells compared to that in control cells at 48 and 72 h (Fig. 7A and B). The expression of myogenin in p110α-deficient cells also treated with TGX-221 was less than that in p110α-deficient cells alone at all time points. The MyHC abundance was reduced in p110α-deficient cells administered TGX-221 compared to that in p110α-deficient cells treated with vehicle after 72 h in DM, suggesting an additive effect of p110β inhibition on differentiation in p110α-deficient cells (Fig. 7A and B). Together, these data demonstrate that inhibition of p110β exacerbates the repressed differentiation caused by p110α deficiency.

FIG 7.

p110β cannot compensate for p110α during myogenic differentiation. (A) C2C12 myoblasts were reverse transfected with control siRNA (si-Con) or siRNA directed against p110α (si-p110α) and maintained in GM for 24 h. Medium was then switched to DM containing DMSO (si-Con and si-p110α) or 1 μM TGX-221 (si-Con + TGX or si-p110α + TGX) for 24, 48, or 72 h before harvest. Representative Western blots using the antibodies indicated on the right are shown. (B) Quantification of myogenin and MyHC blots shown in panel A normalized to the amount of α-tubulin (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments per time point; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, P < 0.01 versus control siRNA at 72 h; ##, P < 0.001 versus control siRNA at 72 h). (C) Primary human skeletal myoblasts were transduced with the control vector (Control), kinase-inactive p110α (p110α-D933A), or kinase-inactive p110α and wild-type p110β (p110α-D933A + p110β-WT) at the time of seeding in DM. All treatments received an equal volume of virus. Protein lysates were harvested at the indicated time points, and Western blotting assays were performed using the indicated antibodies. (D) Quantification of the myogenin and MyHC blots shown in panel C normalized to the amount of α-tubulin (means ± SEMs; n = 3 independent experiments; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

We next tested whether overexpression of p110β was able to compensate for reduced p110α activity in primary human skeletal myoblasts. Myoblasts were transduced with control vector, kinase-inactive p110α (p110α-D933A), or p110α-D933A plus p110β-WT. In cells transduced with p110α-D933A, we observed significant reductions in myogenin levels at 24 and 48 h of differentiation and significant reductions in MyHC levels at 48 and 72 h (Fig. 7C and D). Overexpression of p110β was unable to overcome the reductions induced by p110α-D933A (Fig. 7C and D). These data suggest that p110β cannot compensate for reduced p110α activity during myogenesis.

p110α can compensate for the loss of p110β catalytic activity during myoblast differentiation.

Data from Fig. 5 showed that p110β promoted myoblast differentiation; however, whether p110α was also capable of promoting differentiation to a similar degree was unknown. To address this, primary human skeletal myoblasts were transduced with either an empty control vector or a vector encoding an oncogenic form of p110α (p110α-H1047R) and examined for the expression of differentiation markers. Following 24 h of differentiation, cells expressing p110α-H1047R possessed 40% more myogenin than control cells, although these cells possessed ∼20% less myogenin at 48 h (Fig. 8A and B). There was an ∼2.5-fold increase in MyHC abundance at 48 h in cells expressing p110α-H1047R, while the level of Akt phosphorylation in p110α-H1047R-transduced cells was greater than that in control cells at all time points examined (Fig. 8A and B).

We next tested whether p110α-H1047R could overcome the reduced myoblast differentiation induced by catalytic inhibition of p110β. We found that expression of p110α-H1047R in C2C12 cells increased myogenin abundance by 60% after 24 h of differentiation and that this effect was not suppressed in the presence of TGX-221 (Fig. 8C and D). Additionally, expression of p110α-H1047R increased both the fusion index and the myotube area in human skeletal myoblasts after 72 h of differentiation, even in cells coexpressing catalytically inactive p110β (p110β-K805R) (Fig. 8E and F). Together, these data indicate that p110α is capable of enhancing both human and mouse skeletal myoblast differentiation, even under conditions of p110β catalytic inhibition.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that p110β contributes to early skeletal muscle cell differentiation. During the first 24 h of differentiation, pharmacological blockade of p110β inhibited myoblast proliferation. This observation is consistent with the findings previously presented in reports of studies using other cell models; for example, p110β has been shown to mediate S-phase entry (22) and proliferation of C2C12 myoblasts under growth conditions (24). Taken together, these data suggest that one role for p110β during early differentiation involves regulating cell division prior to myoblast fusion.

Treatment with TGX-221 also reduced muscle-specific transcription factors, MyHC RNA transcripts, and myotube properties at 72 h in C2C12 cells. However, not all of these differences persisted to 96 h. Similarly, we observed greater differences in transcription factor expression and myotube properties at 48 h of differentiation than at 72 h of differentiation in primary human skeletal myoblasts expressing kinase-dead p110β compared to the differences observed in control cells (Fig. 5). Collectively, these findings reveal that differentiation is delayed in cells lacking p110β catalytic activity, suggesting that p110β may play a lesser role in late myogenesis or that p110β-independent mechanisms may partially compensate for the loss of p110β catalytic activity. It should also be noted that other molecular mediators of early myoblast differentiation distinct from classical myogenic transcriptional regulators have been reported. For example, Ste20-like mitogen-activated protein 4 kinase 4 (Map4k4) was found to negatively regulate myogenesis during the early but not late stages of C2C12 differentiation (47).

Young mice lacking p110β in skeletal muscle showed reduced quadriceps mass, strength, and mean fiber cross-sectional area (Fig. 3), but none of these differences were observed between genotypes in the muscles of old mice (data not shown). It is possible that age-specific adaptations that compensate for the loss of p110β exist, although this possibility has yet to be explored.

Following insulin administration, the quadriceps muscle of p110β-mKO mice possessed greater levels of phosphorylated Akt than the quadriceps muscle of insulin-treated p110β-flox mice. These findings are in agreement with those of previous studies reporting increased Akt phosphorylation in response to IGF-I in C2C12 myoblasts treated with siRNA against p110β (24) or in response to insulin/EGF in mammary tumor-derived cells lacking p110β (41). It has been suggested that this hyperactivation of Akt in response to growth factor administration in p110β-deficient cells is due to the increased availability of p110α/p85 heterodimers to associate with activated RTKs (26, 41, 48). This increased availability of p110α/p85 in p110β-deficient cells likely results from a lack of competition for p85 binding from p110β, thereby increasing the proportion of p110α/p85 relative to that of p110β/p85. This is important because p110α is the primary p110 involved in mediating insulin, IGF-I, and EGF signal transduction (25, 49–51), and a greater abundance of p110α than p110β increases the likelihood of p110α interaction with these activated RTKs. Our results support this model and suggest that these compensatory molecular events occur in skeletal muscle in vivo.

Despite our findings that young p110β-mKO mice possessed smaller muscles and decreased strength compared to young control mice, we observed no differences between young p110β-mKO and p110β-flox mice across a number of metabolic determinations (Fig. 4 and data not shown), suggesting that young p110β-mKO mice are metabolically competent. In contrast, old p110β-mKO mice were less glucose tolerant than old p110β-flox mice, a finding inconsistent not only with the glucose tolerance of young p110β-mKO mice (Fig. 4A) but also with previous work showing that glucose tolerance was not impaired by TGX-221 administration (52). One obvious explanation for these discrepancies involves aging itself, as aging has long been known to modify glucose tolerance (53). Additionally, improved glucose tolerance in older mice possessing heterozygous knock-in of kinase-dead p110α (D933A) compared to that in younger mice has been reported (23, 54). Together, these data and ours demonstrate that perturbations in class I PI3K catalytic subunit abundance or function differentially affect glucose tolerance in an age-dependent manner.

We found that overexpression of p110β promoted the differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts and primary human skeletal myoblasts (Fig. 5 and 6). On the surface, these results appear to be inconsistent with previous research showing that siRNA-mediated reduction of p110β increased C2C12 myoblast differentiation (26). However, reductions in p110β also allowed increased activation of p110α and Akt (presumably due to decreased competition from p110β for regulatory subunit binding), and it was this enhanced activation of p110α and Akt that was found to underlie the increased myoblast differentiation in p110β-deficient cells. Ultimately, both p110β-deficient myoblasts (26) and myoblasts overexpressing p110β (this report) possess a p110 isoform capable of stimulating differentiation beyond control levels. Since both p110α and p110β promote PI(3,4,5)P3 formation and recruitment of PI(3,4,5)P3-dependent promyogenic signaling molecules, such as Akt, it is not surprising that differentiation was enhanced under both of these conditions. Thus, these seemingly contradictory observations between studies are actually compatible as well as complementary.

Akt is a well-known modulator of skeletal myoblast differentiation and hypertrophy (55–57), but whether Akt regulated p110β-mediated myogenesis was not known. Primary human skeletal myoblasts overexpressing wild-type p110β showed an almost 3-fold increase in Akt phosphorylation at 24 h of differentiation compared to control myoblasts (Fig. 5). Pharmacological blockade of Akt severely inhibited differentiation, and p110β overexpression was unable to even marginally overcome this, despite its positive effects on differentiation in the absence of the inhibitor. Furthermore, expression of myristoylated Akt1 was able to overcome the inhibition of differentiation induced by TGX-221 administration or by overexpression of kinase-dead p110β. Taken together, these results identify the critical role of Akt in p110β-mediated myogenesis. It is notable, however, that Akt phosphorylation was elevated in p110β-overexpressing human myoblasts only following 24 h of differentiation and not at 48 or 72 h. This suggests that the enhanced differentiation observed in p110β-overexpressing cells may be dependent on the activation of Akt early, rather than late, during the myogenic program. This is further supported by our findings that inhibition of p110β catalytic activity was associated with the greatest reductions in myoblast differentiation during early myogenesis (discussed above).

Prior to this report, the relative contributions of p110α and p110β to skeletal muscle cell differentiation were unknown. In general, cells lacking p110α differentiated more slowly than cells treated with TGX-221 (Fig. 7), suggesting that p110α plays a more prominent role in myoblast differentiation than p110β. However, treatment of p110α-deficient cells with TGX-221 inhibited differentiation to a greater degree than treatment of cells with either p110α or TGX-221 alone, suggesting that both p110 isoforms contribute to myogenesis.

Functional redundancy among p110 isoforms has been observed in insulin signaling, as well as in the proliferation and survival of leukocytes, fibroblasts, and neutrophils (45, 46, 58). However, this redundancy is not observed universally. For example, in liver-specific p110α-knockout mice, insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and p70S6K was dramatically reduced compared to that in the liver of wild-type mice, and forced overexpression of p110β did not restore insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of these molecules (48). Thus, whether p110α and p110β can compensate for one another appears to be specific to the cell type and the stimulus. Our findings suggest that p110α can at least partially compensate for p110β during myogenesis; indeed, expression of oncogenic p110α promoted myoblast differentiation even under conditions of p110β inhibition. Conversely, p110β was not able to compensate for p110α in myogenesis, as evidenced by the inability of overexpressed p110β to restore differentiation in cells expressing kinase-dead p110α. This was surprising because p110β overexpression alone potently stimulated Akt phosphorylation and myogenesis, even under the serum-restricted conditions used to facilitate myoblast differentiation.

The reason behind this discrepancy is not known, especially given the similar functions and substrate specificities of p110α and p110β. It has been shown that p110α possesses a greater lipid kinase activity than p110β, and it has been suggested that p110α may function more efficiently than p110β in membrane areas containing a higher lipid substrate density, whereas the opposite may be true in areas containing a low substrate density (59). On the other hand, p110β has been shown to possess higher protein kinase activity against exogenous substrate than p110α (60). Whether the lipid or protein kinase activities of p110α or p110β are modified during myoblast differentiation remains an open question. It is also possible that the subcellular localization of the p110 isoforms or the availability of inositol lipid substrate within the cell membrane during differentiation may be more permissive for p110α than for p110β. In any case, it appears that p110α activation is important for myogenesis, as reduced p110α activity rendered cells refractory to the promyogenic effects of p110β overexpression.

In conclusion, we found that p110β contributed to early skeletal muscle cell differentiation in cultured cells. The loss of p110β in skeletal muscle of mice resulted in modestly smaller muscles in young, but not old, mice. Long-term reduction of skeletal muscle p110β was also associated with impaired glucose tolerance in old mice. Further identifying the signaling pathways that modulate p110β-mediated myogenesis may allow for targeted therapies to address muscle disease or to enhance regeneration following injury.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funding from Research Area Directorate III, Medical Research and Materiel Command (to R.W.M.), and by NIH grants R01 CA172461-02 (to J.J.Z.) and U24-DK092993 (University of California, Davis, Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center). C.M.L., A.V.G., and M.N.A. were supported by appointments to the Postgraduate Research Participation Program at the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command.

The views, opinions, and/or findings in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official U.S. Department of the Army position, policy, or decision, unless so designated by other official documentation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karalaki M, Fili S, Philippou A, Koutsilieris M. 2009. Muscle regeneration: cellular and molecular events. In Vivo 23:779–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuang S, Rudnicki MA. 2008. The emerging biology of satellite cells and their therapeutic potential. Trends Mol Med 14:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz E, Gibson MC, Champion T. 1978. Satellite cells are mitotically quiescent in mature mouse muscle: an EM and radioautographic study. J Exp Zool 206:451–456. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402060314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauro A. 1961. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 9:493–495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.9.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andres V, Walsh K. 1996. Myogenin expression, cell cycle withdrawal, and phenotypic differentiation are temporally separable events that precede cell fusion upon myogenesis. J Cell Biol 132:657–666. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamir Y, Bengal E. 2000. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase induces the transcriptional activity of MEF2 proteins during muscle differentiation. J Biol Chem 275:34424–34432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida N, Yoshida S, Koishi K, Masuda K, Nabeshima Y. 1998. Cell heterogeneity upon myogenic differentiation: down-regulation of MyoD and Myf-5 generates ‘reserve cells.’ J Cell Sci 111(Pt 6):769–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charge SB, Rudnicki MA. 2004. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol Rev 84:209–238. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh K, Perlman H. 1997. Cell cycle exit upon myogenic differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev 7:597–602. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(97)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi X, Garry DJ. 2006. Muscle stem cells in development, regeneration, and disease. Genes Dev 20:1692–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.1419406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halevy O, Cantley LC. 2004. Differential regulation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase and MAP kinase pathways by hepatocyte growth factor versus. insulin-like growth factor-I in myogenic cells. Exp Cell Res 297:224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang BH, Zheng JZ, Vogt PK. 1998. An essential role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in myogenic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:14179–14183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaliman P, Vinals F, Testar X, Palacin M, Zorzano A. 1996. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors block differentiation of skeletal muscle cells. J Biol Chem 271:19146–19151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch E, Costa C, Ciraolo E. 2007. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases as a common platform for multi-hormone signaling. J Endocrinol 194:243–256. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geering B, Cutillas PR, Nock G, Gharbi SI, Vanhaesebroeck B. 2007. Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinases are obligate p85-p110 heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:7809–7814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700373104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao JJ, Cheng H, Jia S, Wang L, Gjoerup OV, Mikami A, Roberts TM. 2006. The p110alpha isoform of PI3K is essential for proper growth factor signaling and oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:16296–16300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607899103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, Yan H, Gazdar A, Powell SM, Riggins GJ, Willson JK, Markowitz S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE. 2004. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science 304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogt PK, Gymnopoulos M, Hart JR. 2009. PI 3-kinase and cancer: changing accents. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciraolo E, Iezzi M, Marone R, Marengo S, Curcio C, Costa C, Azzolino O, Gonella C, Rubinetto C, Wu H, Dastru W, Martin EL, Silengo L, Altruda F, Turco E, Lanzetti L, Musiani P, Ruckle T, Rommel C, Backer JM, Forni G, Wymann MP, Hirsch E. 2008. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110beta activity: key role in metabolism and mammary gland cancer but not development. Sci Signal 1:ra3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1161577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillermet-Guibert J, Bjorklof K, Salpekar A, Gonella C, Ramadani F, Bilancio A, Meek S, Smith AJ, Okkenhaug K, Vanhaesebroeck B. 2008. The p110beta isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signals downstream of G protein-coupled receptors and is functionally redundant with p110gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:8292–8297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707761105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia S, Liu Z, Zhang S, Liu P, Zhang L, Lee SH, Zhang J, Signoretti S, Loda M, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. 2008. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110beta in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature 454:776–779. doi: 10.1038/nature07091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marques M, Kumar A, Cortes I, Gonzalez-Garcia A, Hernandez C, Moreno-Ortiz MC, Carrera AC. 2008. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases p110alpha and p110beta regulate cell cycle entry, exhibiting distinct activation kinetics in G1 phase. Mol Cell Biol 28:2803–2814. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01786-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foukas LC, Claret M, Pearce W, Okkenhaug K, Meek S, Peskett E, Sancho S, Smith AJ, Withers DJ, Vanhaesebroeck B. 2006. Critical role for the p110alpha phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase in growth and metabolic regulation. Nature 441:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nature04694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matheny RW Jr, Adamo ML. 2010. PI3K p110 alpha and p110 beta have differential effects on Akt activation and protection against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in myoblasts. Cell Death Differ 17:677–688. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knight ZA, Gonzalez B, Feldman ME, Zunder ER, Goldenberg DD, Williams O, Loewith R, Stokoe D, Balla A, Toth B, Balla T, Weiss WA, Williams RL, Shokat KM. 2006. A pharmacological map of the PI3-K family defines a role for p110alpha in insulin signaling. Cell 125:733–747. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matheny RW Jr, Lynch CM, Leandry LA. 2012. Enhanced Akt phosphorylation and myogenic differentiation in PI3K p110beta-deficient myoblasts is mediated by PI3K p110alpha and mTORC2. Growth Factors 30:367–384. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2012.734507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayakawa M, Kaizawa H, Moritomo H, Koizumi T, Ohishi T, Okada M, Ohta M, Tsukamoto S, Parker P, Workman P, Waterfield M. 2006. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 4-morpholino-2-phenylquinazolines and related derivatives as novel PI3 kinase p110alpha inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem 14:6847–6858. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matheny RW Jr, Adamo ML. 2009. Effects of PI3K catalytic subunit and Akt isoform deficiency on mTOR and p70S6K activation in myoblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 390:252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huwiler KG, Machleidt T, Chase L, Hanson B, Robers MB. 2009. Characterization of serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine-1A receptor activation using a phospho-extracellular-signal regulated kinase 2 sensor. Anal Biochem 393:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kost TA, Condreay JP, Ames RS, Rees S, Romanos MA. 2007. Implementation of BacMam virus gene delivery technology in a drug discovery setting. Drug Discov Today 12:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ames R, Fornwald J, Nuthulaganti P, Trill J, Foley J, Buckley P, Kost T, Wu Z, Romanos M. 2004. BacMam recombinant baculoviruses in G protein-coupled receptor drug discovery. Receptors Channels 10:99–107. doi: 10.1080/10606820490514969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tallquist MD, Weismann KE, Hellstrom M, Soriano P. 2000. Early myotome specification regulates PDGFA expression and axial skeleton development. Development 127:5059–5070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson SP, Schoenwaelder SM, Goncalves I, Nesbitt WS, Yap CL, Wright CE, Kenche V, Anderson KE, Dopheide SM, Yuan Y, Sturgeon SA, Prabaharan H, Thompson PE, Smith GD, Shepherd PR, Daniele N, Kulkarni S, Abbott B, Saylik D, Jones C, Lu L, Giuliano S, Hughan SC, Angus JA, Robertson AD, Salem HH. 2005. PI 3-kinase p110beta: a new target for antithrombotic therapy. Nat Med 11:507–514. doi: 10.1038/nm1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch CM, Leandry LA, Matheny RW Jr. 2013. Lysophosphatidic acid-stimulated phosphorylation of PKD2 is mediated by PI3K p110beta and PKCdelta in myoblasts. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 33:41–48. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2012.752005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skapek SX, Rhee J, Spicer DB, Lassar AB. 1995. Inhibition of myogenic differentiation in proliferating myoblasts by cyclin D1-dependent kinase. Science 267:1022–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.7863328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rao SS, Chu C, Kohtz DS. 1994. Ectopic expression of cyclin D1 prevents activation of gene transcription by myogenic basic helix-loop-helix regulators. Mol Cell Biol 14:5259–5267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bader D, Masaki T, Fischman DA. 1982. Immunochemical analysis of myosin heavy chain during avian myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Cell Biol 95:763–770. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sumitani S, Goya K, Testa JR, Kouhara H, Kasayama S. 2002. Akt1 and Akt2 differently regulate muscle creatine kinase and myogenin gene transcription in insulin-induced differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts. Endocrinology 143:820–828. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.3.8687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beylkin DH, Allen DL, Leinwand LA. 2006. MyoD, Myf5, and the calcineurin pathway activate the developmental myosin heavy chain genes. Dev Biol 294:541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Utermark T, Rao T, Cheng H, Wang Q, Lee SH, Wang ZC, Iglehart JD, Roberts TM, Muller WJ, Zhao JJ. 2012. The p110alpha and p110beta isoforms of PI3K play divergent roles in mammary gland development and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 26:1573–1586. doi: 10.1101/gad.191973.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang BH, Aoki M, Zheng JZ, Li J, Vogt PK. 1999. Myogenic signaling of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase requires the serine-threonine kinase Akt/protein kinase B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:2077–2081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rotwein P, Wilson EM. 2009. Distinct actions of Akt1 and Akt2 in skeletal muscle differentiation. J Cell Physiol 219:503–511. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vandromme M, Rochat A, Meier R, Carnac G, Besser D, Hemmings BA, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ. 2001. Protein kinase B beta/Akt2 plays a specific role in muscle differentiation. J Biol Chem 276:8173–8179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foukas LC, Berenjeno IM, Gray A, Khwaja A, Vanhaesebroeck B. 2010. Activity of any class IA PI3K isoform can sustain cell proliferation and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:11381–11386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906461107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaussade C, Rewcastle GW, Kendall JD, Denny WA, Cho K, Gronning LM, Chong ML, Anagnostou SH, Jackson SP, Daniele N, Shepherd PR. 2007. Evidence for functional redundancy of class IA PI3K isoforms in insulin signalling. Biochem J 404:449–458. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang M, Amano SU, Flach RJ, Chawla A, Aouadi M, Czech MP. 2013. Identification of Map4k4 as a novel suppressor of skeletal muscle differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 33:678–687. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00618-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sopasakis VR, Liu P, Suzuki R, Kondo T, Winnay J, Tran TT, Asano T, Smyth G, Sajan MP, Farese RV, Kahn CR, Zhao JJ. 2010. Specific roles of the p110alpha isoform of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in hepatic insulin signaling and metabolic regulation. Cell Metab 11:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McMullen JR, Shioi T, Huang WY, Zhang L, Tarnavski O, Bisping E, Schinke M, Kong S, Sherwood MC, Brown J, Riggi L, Kang PM, Izumo S. 2004. The insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor induces physiological heart growth via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110alpha) pathway. J Biol Chem 279:4782–4793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hill K, Welti S, Yu J, Murray JT, Yip SC, Condeelis JS, Segall JE, Backer JM. 2000. Specific requirement for the p85-p110alpha phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase during epidermal growth factor-stimulated actin nucleation in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 275:3741–3744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jia S, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. 2009. Should individual PI3 kinase isoforms be targeted in cancer? Curr Opin Cell Biol 21:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith GC, Ong WK, Rewcastle GW, Kendall JD, Han W, Shepherd PR. 2012. Effects of acutely inhibiting PI3K isoforms and mTOR on regulation of glucose metabolism in vivo. Biochem J 442:161–169. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leiter EH, Premdas F, Harrison DE, Lipson LG. 1988. Aging and glucose homeostasis in C57BL/6J male mice. FASEB J 2:2807–2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Foukas LC, Bilanges B, Bettedi L, Pearce W, Ali K, Sancho S, Withers DJ, Vanhaesebroeck B. 2013. Long-term p110alpha PI3K inactivation exerts a beneficial effect on metabolism. EMBO Mol Med 5:563–571. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lai KM, Gonzalez M, Poueymirou WT, Kline WO, Na E, Zlotchenko E, Stitt TN, Economides AN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. 2004. Conditional activation of Akt in adult skeletal muscle induces rapid hypertrophy. Mol Cell Biol 24:9295–9304. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9295-9304.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]