Abstract

An 85-year-old man with HCV infection and diabetes mellitus was diagnosed as having hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, 13 cm in diameter) based on high serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), AFP-L3, and des-γ-carboxy prothrombin levels as well as typical enhancement pattern on contrast-enhanced CT. The patient did not receive any interventional treatments because of advanced age and the advanced stage of HCC. He chose to take vitamin K, which was reported to suppress the growth of HCC in vitro. Three months after starting vitamin K, all three tumor markers were normalized and HCC was markedly regressed, showing no enhancement in the early arterial phase on CT. Here we present the report describing the regression of HCC during the administration of vitamin K.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Vitamin K, Reg-ression

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide[1]. HCC is developed mainly in patients with chronic hepatitis C or B virus infections and the screening of this high risk group makes it possible to detect HCC at the early stage. However, many patients are still diagnosed at the advanced stage and the prognosis is poor. Transcatheter chemoembolization or chemotherapies are performed in cases of advance HCC[1-3]. These treatments are sometimes very effective, but are harmful to the background liver and accelerate the progression of pre-existing chronic liver injury. Therefore, these therapies cannot be performed in patients with severe liver cirrhosis. In addition, severe side effects often impair the quality of life. Thus, the development of new low-invasive therapies is needed.

Vitamin K is a factor in blood coagulation and is used for the treatment of osteoporosis[4]. Vitamin K is also known to inhibit the growth of cancer cell lines, but its clinical usefulness in the treatment of human cancer remains controversial[5-7]. In this report, we present a case of advanced HCC in which marked regression during the administration of vitamin K has been documented.

CASE REPORT

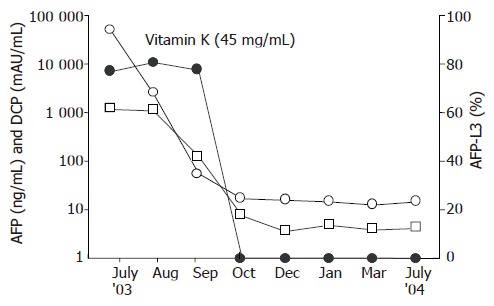

In July 2003, an 85-year-old man with liver cirrhosis due to HCV and diabetes mellitus was admitted to our hospital because of giant liver tumors. The patient had no history of alcohol drinking or blood transfusion. He did not smoke and was not taking any medicine, but was under intermediate-acting insulin (12 U/d) injection. He had undergone surgery for prostate hypertrophy 3 years before the present admission. Routine laboratory studies showed Hb 13.8 g/L, platelet count 101 000/mm3, albumin 3.2 g/L, total bilirubin 0.6 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase 232 U/L and 102 U/L respectively, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase 93 IU/L, fasting blood glucose 126 mg/dL, HbA1c 11.1%. Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), lentil lectin-A-reactive AFP (AFP-L3), and des-γ-carboxy prothrombin (DCP) were 1 212 ng/mL, 76.9%, and 51 300 mAU/mL, respectively. The patient was positive for HCV antibody and hepatitis B virus core antigen but negative for hepatitis B virus surface antibody. There were no esophageal or gastric varices observed during gastro-intestinal endoscopy. Although the patient did not complain of abdominal pain, gastric ulcer was detected by endoscopy and administration of the proton pump inhibitor was started.

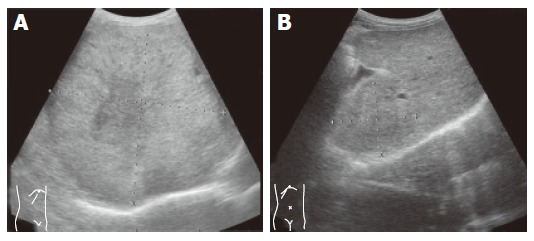

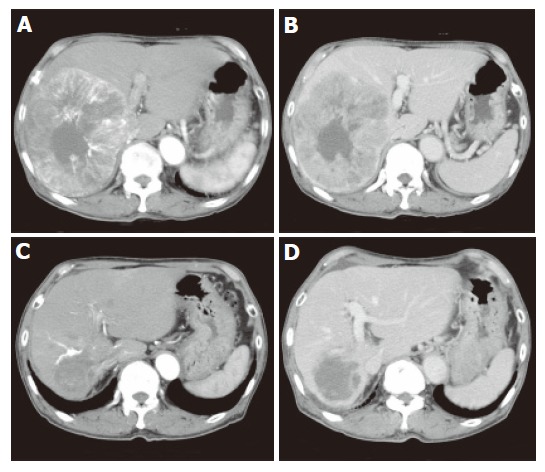

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) demonstrated that a large hyperechoic mass (13 cm in diameter) with central hypoechoic area dominated the right lobe of the liver (Figure 1A). At least four nodules about 2 cm in diameter surrounded the main nodule and another nodule (5 cm in diameter) existed at segment 4. Portal vein (PV) in the right lobe was replaced by tumor except for the PV in segments 5 and 8 in which faint blood flow was observed. Right hepatic vein was replaced and the middle hepatic vein was stretched by the tumor. Enhancement during the early arterial phase and defect during portal phase were observed by contrast enhanced-computed tomography (CE-CT, Figures 2A and B). Based on typical imaging features and elevated HCC tumor markers, the liver tumors were diagnosed as HCC. There was no distant metastasis observed by chest X-ray or abdominal CT.

Figure 1.

Giant tumor with central hypoechoic area dominated the right lobe of the liver (A) and remarkable regression of tumor with obscure margin after administration of vitamin K (B).

Figure 2.

Enhancement of peripheral portion of tumor during early arterial phase (A) and hypoattenuation during portal phase (B) as well as remarkable tumor regression and no enhancement during early arterial phase (C) and portal phase (D) 5 mo after administration of vitamin K.

Because of the patient’s advanced age and advanced stage of HCC, the patient declined interventional therapies or angiography. Thereafter, we prescribed oral vitamin K2 (45 mg daily), which was reported to inhibit cancer growth in vitro[4,5]. The recommended dose for osteoporosis therapy was used. Informed consent for the administration of vitamin K was obtained from the patient and his family. Soon after the administration of vitamin K, AFP as well as DCP decreased and finally normalized in the 3rd month. AFP-L3 also decreased to below the detectable level from 76.9% to 0% (Figure 3). CE-CT, 5 months after starting vitamin K, demonstrated that the tumor sizes were remarkably decreased and the diameter of the main tumor was 5.5 cm (Figures 2C and D). Enhancement during the early arterial phase had disappeared in all nodules. US demonstrated that the tumor regressed and the margin of the tumor became obscure (Figure 1B). Twenty-two months have passed and there are no signs of recurrence observed to date. All three tumor markers have remained within the normal limits.

Figure 3.

Clinical course of the patient.

DISCUSSION

Vitamin K is known to inhibit the growth of many cancer cell lines including HCC[5-7]. The mechanisms of the anticancer action of vitamin K are not precisely understood, but several candidates including the induction of apoptosis, differentiation, and cell cycle inhibition have been proposed[4]. Recent research has demonstrated that the anticancer action of vitamin K may occur at the level of tyrosine kinases and phosphatase, modulating various transcription factors. In addition to the in vitro analysis, there are several case reports that described the usefulness of vitamin K for the treatment of human cancers including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)[6,7]. In a clinical trial of vitamin K for MDS and post-MDS acute myeloid leukemia, hematological improvement is reported in four of nine patients[8]. Recently, Koike et al demonstrated that the development of PV tumor thrombus is inhibited and patient’s survival is improved in patients with HCC following administration of vitamin K (unpublished data). These reports suggest that vitamin K is an anticancer agent for HCC.

Spontaneous regression of cancer is rare and estimated to occur once in 60 000-100 000 patients with cancer[9]. At least 27 cases of spontaneous regression of HCC have been reported[10-14]. There were no apparent clinical characteristics discriminating the patient with spontaneous regression of HCC from others and various causes of regression have been documented (e.g. lack of blood supply due to arterial infarction or rapid growth of HCC, withdrawal from steroids, abstinence of alcohol consumption, administration of herbal medicines, and immunological activation due to high fever or sepsis)[10,15]. Hepatic angiography was performed in some cases and blood shortage due to the intimal damage induced by micro catheters could also be the cause of regression. In this report, the speed of tumor growth was uncertain because the patient was not followed up before admission. Other than that, he did not have any of the background factors reported previously. Therefore, possible reasons for regression are limited in this case; spontaneous regression due to blood shortage induced by rapid tumor growth or regression due to vitamin K administration, which was reported to inhibit tumor growth.

Although we could not conclude that administration of vitamin K was the cause of the regression in this case, this is a case report documenting regression of HCC during the administration of vitamin K. Further prospective study is needed to confirm the efficacy of vitamin K for the treatment of HCC.

Footnotes

Science Editor Wang XL and Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung TW, Johnson PJ. Systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:514–520. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony PP. Hepatocellular carcinoma: an overview. Histopathology. 2001;39:109–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamson DW, Plaza SM. The anticancer effects of vitamin K. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:303–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Wang M, Finn F, Carr BI. The growth inhibitory effects of vitamins K and their actions on gene expression. Hepatology. 1995;22:876–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaguchi M, Miyazawa K, Otawa M, Katagiri T, Nishimaki J, Uchida Y, Iwase O, Gotoh A, Kawanishi Y, Toyama K. Vitamin K2 selectively induces apoptosis of blastic cells in myelodysplastic syndrome: flow cytometric detection of apoptotic cells using APO2.7 monoclonal antibody. Leukemia. 1998;12:1392–1397. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimaki J, Miyazawa K, Yaguchi M, Katagiri T, Kawanishi Y, Toyama K, Ohyashiki K, Hashimoto S, Nakaya K, Takiguchi T. Vitamin K2 induces apoptosis of a novel cell line established from a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome in blastic transformation. Leukemia. 1999;13:1399–1405. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyazawa K, Nishimaki J, Ohyashiki K, Enomoto S, Kuriya S, Fukuda R, Hotta T, Teramura M, Mizoguchi H, Uchiyama T, et al. Vitamin K2 therapy for myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and post-MDS acute myeloid leukemia: information through a questionnaire survey of multi-center pilot studies in Japan. Leukemia. 2000;14:1156–1157. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201–209. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930170302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin TJ, Liao LY, Lin CL, Shih LS, Chang TA, Tu HY, Chen RC, Wang CS. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:579–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iiai T, Sato Y, Nabatame N, Yamamoto S, Makino S, Hatakeyama K. Spontaneous complete regression of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1628–1630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morimoto Y, Tanaka Y, Itoh T, Yamamoto S, Mizuno H, Fushimi H. Spontaneous necrosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. Dig Surg. 2002;19:413–418. doi: 10.1159/000065822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abiru S, Kato Y, Hamasaki K, Nakao K, Nakata K, Eguchi K. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with elevated levels of interleukin 18. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:774–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeda M, Okada S, Ueno H, Okusaka T, Kuriyama H. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma with multiple lung metastases: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2001;31:454–458. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hye092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeda Y, Togashi H, Shinzawa H, Miyano S, Ishii R, Karasawa T, Takeda Y, Saito T, Saito K, Haga H, et al. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma and review of literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1079–1086. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]