Abstract

Background:

This cross-sectional study was designed to measure the level and distribution of job satisfaction of registered dental practitioners and to explore the factors associated with it.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted among 66 registered dentists in Srikakulam, India. Job satisfaction was measured by using a modified version of the Dentists Satisfaction Survey questionnaire. The statistical tests employed were “t” test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc test (Scheffe test) was employed for multiple comparisons.

Results:

The response rate was 82.5%. The mean score of overall job satisfaction among dentists was 3.08 out of 5. The most satisfying aspect was income (3.7) and the least satisfying aspect was staff (2.5). Overall satisfaction increased with age. Male practitioners showed less satisfaction with staff, income, and overall satisfaction and more satisfaction in professional relations and time, when compared to females. Job satisfaction was found to be more in practitioners with postgraduate qualification.

Conclusion:

This study suggests that patient relations, perception of income, personal time, and staff are the important factors for job satisfaction among dentists. The findings of this study will be helpful to policymakers to design plans in order to increase the level of job satisfaction.

Keywords: Career satisfaction, dental practitioners, India

INTRODUCTION

Dentistry is a profession with a wide range of possible pitfalls where dentists are subject to wide variety of occupational factors that greatly affect their well-being.[1,2] Many studies have shown high prevalence of physical and psychological disorders in dental practice also.[3,4] Therefore, it is hardly surprising that dentistry has even been classified as a hazardous profession.[5] However, as any other profession, dentistry is a rewarding job as well. Various elements at dental work – dentists’ social recognition, position in society, self-realization, and many other factors in everyday practice – give and increase job satisfaction. Also, job satisfaction is the most important factor for successful practice. Many factors contribute to job satisfaction. A study of job satisfaction among dentists in the US state of California by Shugars et al.[6] suggests that possible determinants of job satisfaction among dentists, such as dentist attributes and physical and emotional well-being, need to be studied. One study reported that patient relations, income, staff, and speciality training are positively associated with job satisfaction among dentists.[7] Patient relations were found to affect dentists’ professional satisfaction as evidenced in some studies.[7,8,9] Job satisfaction may be improved by developing an area of special interest and further training.

Job satisfaction is described at this point as a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one's job or job experience. Job satisfaction results from the perception that one's job fulfils or allows the fulfillment of one's own important job values, providing that and to the degree that those values are congruent with one's needs. According to Kreitner et al.,[10] job satisfaction is an affective and emotional response to various facets of one's job.

Dental profession is not only a source of income, but something more: It enriches the dentist and gives pleasure, joy, and motivation to work. This job motivation helps to improve the patient care. As a result, both doctor and patient and the entire dental care system enjoy benefit. Therefore, it is important to understand dentists’ job satisfaction and the factors influencing it.

Hence, a study was undertaken with an aim to assess the level of job satisfaction among dental practitioners in Srikakulam, India. Srikakulam is the extreme northeastern district of Andhra Pradesh, situated within the geographic co-ordinates of 18°-20′ and 19°-10′ N and 83°-50′ and 84°-50′ E. Approximately 80 dental practitioners are registered in the Indian Dental Association, Srikakulam branch, which includes full-time practitioners, part-time practitioners, and those who are associated with academics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

A questionnaire-based survey was conducted to assess the job satisfaction among dental practitioners in Srikakulam district.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for conducting the survey was obtained from the ethical committee of Sree Sai Dental College and Research Institute.

Study population

Convenient sampling technique was used in this study, where all dental practitioners registered in the Indian Dental Association, Srikakulam branch were approached. Dentists who had retired from the profession, had changed their profession, or were pursuing postgraduation and full-time academicians were excluded from the study. The study period was 2 months during which 80 dental practitioners were approached of which 14 members refused to participate in the study. Time duration of approximately 24 h was given to the respondents to complete the questionnaire, and the investigator himself collected the completed forms after the said period.

Informed consent

Verbal consent was obtained from the dental practitioners and they were assured that the information would be held confidential.

Questionnaire

A modified version of the Dentists Satisfaction Survey (DSS) inventory[11] was used. The questionnaire consists of six parts. In the first part, demographic data are included. The second part contains items that measure satisfaction in relation to staff, third part measures their satisfaction with income, fourth part contains items that measure satisfaction in terms of professional relations, fifth part measures satisfaction in relation to professional time, and the sixth part measures overall job satisfaction among the dental practitioners. The questionnaire consists of demographic data and 25 questions graded on a 5-point Likert scale having the options, strongly disagree (SD), disagree (D), neither agree nor disagree (N), agree (A), and strongly agree (SA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was undertaken using SPSS version 12.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago II, United States of America). The statistical tests employed were t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) at 95% confidence interval. For multiple comparisons, post hoc test (Scheffe test) was employed and the significance level was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

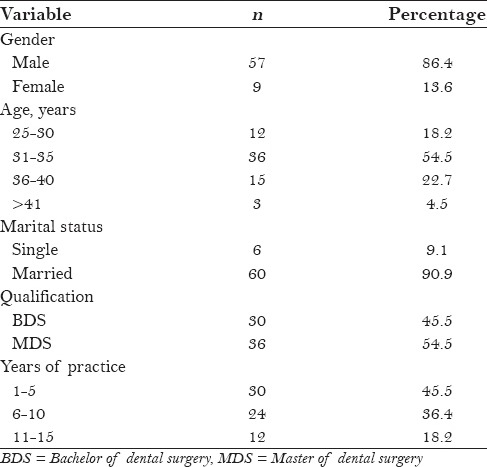

Out of the 80 dentists who were approached to participate in the survey, 66 agreed and completed the questionnaire, giving a response rate of 82.5%. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample population are presented in Table 1. Majority of the dental practitioners were males with a mean age of 34.04 ± 4.1 years, had > 5 years of experience in dental practice, and were mostly married.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

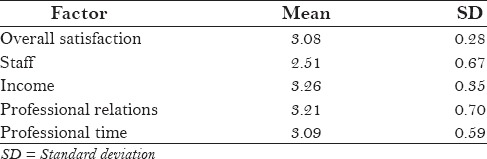

The mean score of overall professional satisfaction of the studied population was 3.08 ± 0.28 and the satisfaction level was found to be neutral (partly satisfied). Among the different factors studied, the most satisfying aspect overall was income (3.26 ± 0.35), followed by professional relations (3.21 ± 0.70) and professional time (3.09 ± 0.59), and the least satisfaction was with staff (2.51 ± 0.67) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Satisfaction levels of various factors in the sample studied

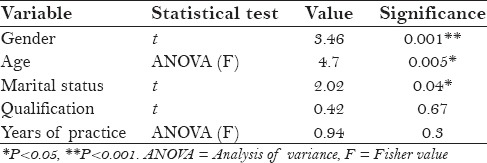

Overall professional satisfaction

An analysis of the overall professional satisfaction in relation to different age groups revealed that levels of overall professional satisfaction varied with age; it was found to be more in 36–40 years age group and least in 41–46 years age group. There was a statistically significant difference between all the age groups. When multiple comparisons were done, significant differences were found between the first three age groups and the last age group, but no significance was found among the first three age groups. Males had an overall professional satisfaction of 3.03 ± 0.28 and females had a satisfaction level of 3.37 ± 0.13. There was a statistically significant difference between males and females, with females having higher satisfaction levels (P < 0.05).

Overall satisfaction was higher in those practitioners who were married (3.1 ± 0.29) when compared to those who are unmarried (2.86 ± 0.09) and the difference was found to be significant (P < 0.05).

When overall satisfaction was compared between qualifications, it was found that those who had postgraduate qualification had a higher mean level of overall satisfaction (3.1 ± 0.26) when compared to those who did not have a postgraduate degree (3.06 ± 0.31). There was no statistical significance in satisfaction between those with postgraduate qualification and those without (P = 0.67).

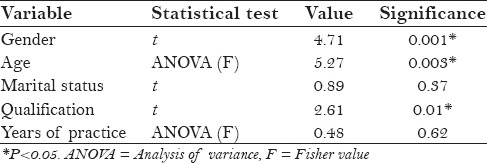

Dental practitioners who had clinical experience between 1 and 5 years were found to have higher satisfaction levels (3.12 ± 0.31) when compared to those having an experience of more than 5 years. However, there was no significant difference in satisfaction levels regarding clinical experience [Table 3].

Table 3.

Overall satisfaction and its association with various demographic factors

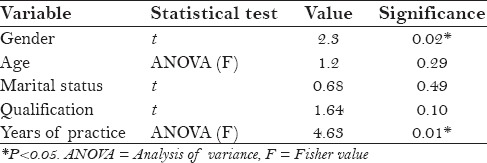

Satisfaction with other factors

Staff

The mean score of dental practitioners’ satisfaction with their staff was 2.51 ± 0.67 and the satisfaction level was found to be neutral (partly satisfied).

When this factor was compared in different age groups, it showed that practitioners in the age group of 36–40 years were more satisfied with their staff and those in the age group of 41–46 years were least satisfied. There was no statistically significant difference between the age groups. Male practitioners were less satisfied with their staff (2.43 ± 0.69) when compared with females (3.0 ± 0.28). There was a statistically significant difference between males and females, with females having higher satisfaction (P < 0.05).

Accordingly, practitioners who were married had higher satisfaction (2.53 ± 0.7) when compared to those who are unmarried (2.33 ± 0.0) and the difference was not significant (P = 0.49).

When compared between qualifications, it was found that those who had postgraduate qualification had a higher satisfaction (2.63 ± 0.77) when compared to those who did not had postgraduate qualification (2.36 ± 0.51). There was no statistically significant difference in satisfaction between those with postgraduate qualification and those without (P = 0.10).

Dental practitioners who had clinical experience between 1 and 5 years were found to have higher satisfaction with staff (2.76 ± 0.71) and those with 11–15 years experience had least satisfaction (2.16 ± 0.30). There was significant difference in the satisfaction of practitioners with different clinical experiences. When multiple comparisons were made between the three groups, it was found that a significant difference existed between those with 1–5 years clinical experience and those with 11–15 years clinical experience [Table 4].

Table 4.

Satisfaction with staff and its association with various demographic factors

Income

The mean score of the dental practitioners’ satisfaction in relation to income was 3.26 ± 0.35 and the satisfaction level was found to be neutral (partly satisfied).

When this factor was compared in different age groups, it showed that practitioners in the age group of 36–40 years were more satisfied with their income (3.37 ± 0.22) and those in the 41–46 years age group were least satisfied (2.57 ± 0.0). There was no statistically significant difference between the age groups. Upon multiple comparisons, significant difference was found between the first three age groups and the last age group. Male practitioners were less satisfied with their income (3.19 ± 0.32) when compared with females (3.71 ± 0.08). There was a statistically significant difference between males and females, with females having higher satisfaction (P < 0.05).

Satisfaction with income was higher in practitioners who were married (3.27 ± 0.34) when compared to those who were unmarried (3.14 ± 0.46) and the difference was not significant (P = 0.37).

When compared between qualifications, it was found that those who had postgraduate qualification had a higher satisfaction (3.38 ± 0.40) when compared to those who did not have postgraduate qualification (3.16 ± 0.27) and the difference was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Dental practitioners who had clinical experience between 6 and 10 years were found to have higher satisfaction with income (3.32 ± 0.26) and those with 11–15 years experience had least satisfaction (3.21 ± 0.40). There was no significant difference in satisfaction for practitioners with different clinical experience. When multiple comparisons were made between the three groups, it was found that there was no significant difference among them [Table 5].

Table 5.

Income and its association with various demographic factors

Professional relations

The mean score of dental practitioners’ satisfaction with professional relations was 3.21 ± 0.70 and the satisfaction level was found to be neutral (partly satisfied).

Practitioners in the age group of 41–46 years were more satisfied with their professional relations (3.33 ± 0.0) and those in the age group of 25–30 years were least satisfied (3.08 ± 0.83). There was no statistically significant difference between the age groups for this factor. Male practitioners were less satisfied with their professional relations (3.17 ± 0.73) when compared with females (3.44 ± 0.44). No significant difference was found between males and females in their satisfaction with the professional relations.

Professional relations were maintained well by the practitioners who were married (3.25 ± 0.67) when compared to those who are unmarried (2.83 ± 0.91) and the difference was not significant (P = 0.17).

When compared between qualifications, it was found that those who had postgraduate qualification had a higher satisfaction (3.26 ± 0.49) when compared to those who did not have postgraduate qualification (3.16 ± 0.84) and the difference was not statistically significant (P < 0.57).

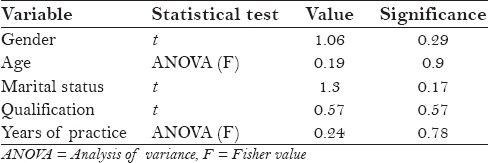

Dental practitioners who had clinical experience between 6 and 10 years were found to have higher satisfaction in their professional relations (3.25 ± 0.82) and those with 11–15 years experience had least satisfaction (3.08 ± 0.28). There was no significant difference in satisfaction about the professional relations for practitioners with different clinical experience. When multiple comparisons were made between the three groups, it also showed that there was no significant difference among them [Table 6].

Table 6.

Professional relations and its association with various demographic factors

Professional time

The mean score of dental practitioners’ satisfaction for professional time was 3.09 ± 0.59 and the satisfaction level was found to be neutral (partly satisfied).

Practitioners in the age group of 36–40 years were more satisfied with their professional time (3.40 ± 0.18) and those in the 41–46 years age group were least satisfied (2.40 ± 0.0). Statistically significant difference was found between the age groups in their satisfaction toward professional time. However, multiple comparisons showed that a significant difference existed between 36–40 years age group and 41–46 years age group. Male practitioners were less satisfied with their professional time (3.06 ± 0.26) when compared to females (3.09 ± 0.83). No significant difference was found between males and females for this factor.

Practitioners who were married were more satisfied with professional time (3.12 ± 0.59) when compared to those who are unmarried (2.80 ± 0.43) and the difference was not significant (P = 0.20).

When compared between qualifications, it was found that those who had postgraduate qualification had a higher satisfaction (3.13 ± 0.66) when compared to those who did not have postgraduate qualification (3.04 ± 0.49) and the difference was not statistically significant (P < 0.57).

Dental practitioners who had clinical experience between 1 and 5 years were found to have higher satisfaction with their professional time (3.12 ± 0.67) and those with 6–10 years experience had least satisfaction (3.07 ± 0.56). There was no significant difference for satisfaction related to professional time among the practitioners with different clinical experience. When multiple comparisons were made between the three groups, it also showed that there was no significant difference among them [Table 7].

Table 7.

Professional time and its association with various demographic factors

DISCUSSION

Job satisfaction is an indicator of a person's attitude toward his profession. This study was undertaken to measure professional satisfaction among dental practitioners in Srikakulam, India. In this study, a modified DSS questionnaire was used to assess professional satisfaction. This study included only 66 dental practitioners from Srikakulam. So, the findings of this study may have limited generalizability and may need to be confirmed by further research on a larger sample. Our survey was mainly conducted to know the satisfaction levels of dental practitioners regarding their staff, income, professional relations, professional time, and their overall professional satisfaction.

Professional satisfaction among the practitioners was found to be neutral (partly satisfied) with a mean of 3.08 ± 0.28. This was found to be lower when compared with those of Korean dentists[7] (3.2 ± 0.03), Canadian orthodontists[8] (4.0 ± 0.63), and Lithuanian dentists[9] (4.60 ± 0.10). Satisfaction among dentists showed variation in different age groups. This finding is similar to the finding of Luzzi et al.,[12] but contrary to the findings of Shugars et al.[6] and Purine et al.[9] where satisfaction increased with age. Low satisfaction level in 41–46 years age group may be attributed to various aspects of life like responsibilities for children, investment for their higher education, employment of the children, and their marriage, which are considered to be utmost important and the responsibilities of the family head.

Overall satisfaction was found to be more among females when compared to males. This finding was similar to the report of Luzzi et al.[12] These gender differences highlighted the fact that women are more satisfied in the overall professional satisfaction dimension that measured satisfaction with self, career, and their family. In this study, dentists having postgraduate qualification were found to have higher levels of overall professional satisfaction when compared to those who did not have the same. This low level of satisfaction in undergraduate dentists may be attributed to their fear about career aspirations and their feeling of being trapped in dentistry. Dentists who were married had high levels of professional satisfaction when compared to those who are unmarried, which may be due to having well-settled life and their inability to drop job or change career due to family responsibilities.

Dentists’ satisfaction about work performance of their staff decreased with age; young dentists were found to be more satisfied with this factor, which may be related to their starting of career and friendly nature with their auxiliary personnel. Satisfaction about this factor was low among dentists of old age, which can be due to various factors like complaints of patients regarding dentures, broken dentures, faulty restorations, getting angry upon patients, and so on. Male practitioners were less satisfied with their staff when compared to female practitioners; this may be due to the fact that most of the clinics run by male practitioners had more number of auxiliaries and staff when compared to those run by female practitioners. Dentists with postgraduate qualification showed more satisfaction toward their staff when compared to dentists without postgraduation; this is because in Srikakulam, most of the clinics are managed by dentists with postgraduation and those without postgraduation are mostly working staff in clinics.

Satisfaction about income increased with age of the dentist and was more in females, married practitioners, and those with postgraduation qualification, but this difference was not significant. This is based on the belief that the amount of effort exerted on a job depends on the expected return and may result in increased pleasure and that people may perform their job and be satisfied.

Similarly, satisfaction about professional relations and professional time also increased with age and was more in females, married dentists, and in those with postgraduate qualification, and showed no significant differences. Many female dentists may work less than full-time, but as the employment status was not collected in this study, it is difficult to ascertain if this is the reason for women reporting higher levels of satisfaction in this dimension. However, Teusner and Spencer[13] found that female dentists work significantly fewer hours than male dentists. Introducing more flexible working hours into the workplace for both sexes might reduce dissatisfaction with the job encroaching on personal time.

Majority of those included in the study were partly satisfied with the dental profession as a career. This study also indicated that the male respondents were more dissatisfied with their income, staff, professional relations, and time spent with each patient. This may indicate concerns about autonomy. Significant differences in satisfaction were found only for overall satisfaction, staff, and income. There is a need to confirm and replicate the findings of this study through other research methods and in other settings.

Team building activities are recommended for increasing the job satisfaction, which strengthen interpersonal relationships, improve staff communication, and help them understand and clarify their roles.

CONCLUSION

Satisfaction with one's job can affect not only motivation at work but also career decisions, relationships with others, and personal health. Those who work in a profession that is extremely demanding and sometimes unpredictable can be susceptible to feelings of uncertainty and reduced job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction of dental practitioners is also an essential part of ensuring high quality care. Dissatisfied dentist may give poor-quality and less-efficient care.

The findings of this study showed a medium level of job satisfaction among the dental professionals studied. Factors found to influence job satisfaction were staff, income, and overall satisfaction. No significant association was found between socio-demographic characteristics and job satisfaction with respect to professional relations and time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial interests, direct or indirect, for any of the authors do not exist for this article. Sources of outside support of the project are none for this article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Myers HL, Myers LB. ‘It's difficult being a dentist’: Stress and health in the general dental practitioner. Br Dent J. 2004;197:89–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811476. discussion 83; quiz 100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puriene A, Janulyte V, Musteikyte M, Bendinskaite R. General health of dentists. Literature review. Stomatologija. 2007;9:10–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puriene A, Aleksejuniene J, Petrauskiene J, Balciuniene I, Janulyte V. Occupational hazards of dental profession to psychological wellbeing. Stomatologija. 2007;9:72–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leggat PA, Kedjarune U, Smith DR. Occupational health problems in modern dentistry: A review. Ind Health. 2007;45:611–21. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermanson PC. Dentistry: A hazardous profession. Dent Stud. 1972;50:60–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shugars DA, DiMatteo MR, Hays RD, Cretin S, Johnson JD. Professional satisfaction among California general dentists. J Dent Educ. 1990;54:661–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong SH, Chung JK, Choi YH, Sohn W, Song KB. Factors related to job satisfaction among South Korean dentists. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:460–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth SF, Heo G, Varnhagen C, Glover KE, Major PW. Job satisfaction among Canadian orthodontists. Am J Othodontics Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:695–700. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puriene A, Petrauskiene J, Janulyte V, Balciuniene I. Factors related to job satisfaction among Lithuanian dentists. Stomatologija. 2007;9:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krietner R, Kinicki A, Buelens M. 2nd ed. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill; 2002. Organizational Behaviour. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shugars DA, Hays RD, DiMatteo M, Cretin S. Development of an instrument to measure job satisfaction among dentists. Med Care. 1991;29:728–44. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luzzi L, Spencer AJ, Jones K, Teusner D. Job satisfaction of registered dental practitioners. Aust Dent J. 2005;50:179–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teusner DN, Spencer AJ. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2003; 2000. Dental Labour Force, Australia. [Google Scholar]