Abstract

Congenital duplication of the common bile duct is an extremely rare anomaly of the biliary tract, which putatively represents failure of regression of the embryological double biliary system. Depending on the morphology of the duplicated bile duct, the anomaly can be classified into five distinct subtypes as per the modified classification (proposed by Choi et al). Among the five subtypes of bile duct duplication, type V duplication is considered to be the least common with only two previous cases of type Va variant reported in medical literature prior to the current report.

Keywords: Common bile duct, double, duplicated

Conventional biliary anatomy is believed to be present in 58% of the population while as many as 42% of patients show anatomical variations in their biliary anatomy mostly pertaining to the intrahepatic biliary system—the most common variants being aberrant drainage of right posterior duct into the left hepatic duct, and, the so-called triple confluence representing simultaneous emptying of the right posterior sectoral duct, right anterior sectoral duct, and the left hepatic duct into the common hepatic duct.[1,2] In contrast, duplication of the extrahepatic bile duct is one of the rarest congenital variant that has been sparingly reported, with about 30 cases reported in Western literature.[2] This intriguing anomaly has been reported in association with anomalous biliopancreatic junction, congenital choledochal cysts, and biliary atresia and can predispose to complications such as choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, pancreatitis, and malignancies, including cholangiocarcinoma and cancer of the upper gastrointestinal tract.[1,2,3,4,5]

CASE REPORT

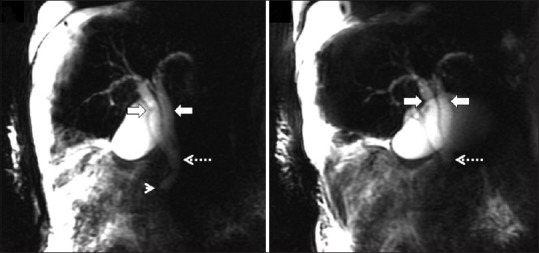

A 52-year-old woman, a previously diagnosed case of cryptogenic cirrhosis, presented with progressive worsening of jaundice and unrelenting right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Previously, her work-up for known etiologies of chronic liver disease (including hepatitis viral serology, autoantibodies such as antinuclear and antismooth muscle antibodies, serum ferritin, and ceruloplasmin levels) were negative. At present admission, her liver biochemistry revealed total, direct, and indirect bilirubin of 7.8, 4.1, and 3.7 mg/dL, respectively. Serum alkaline phosphatase was elevated at 264 IU/L, whereas alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase were only marginally raised. Ultrasonography of abdomen revealed biliary dilatation with suspicion of an intraductal calculus impacted at the ampulla. Interestingly, subsequent magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed duplication of the extrahepatic bile duct [Figure 1]. The duplicated bile ducts were running parallel and were seen to reunite into a common channel at the level of the head of the pancreas consistent with type-Va double common bile duct according to Choi et al. Additionally, a filling-defect suggestive of an obstructive calculus was seen in the common channel just above the ampulla causing obstruction and upstream biliary dilatation (arrow). No associated anomaly of the gallbladder was evident. The cystic duct was seen inserting into the right-sided bile duct. The biliopancreatic junction was unremarkable.

Figure 1.

Thick slab (2D) MRCP image showing duplicated extrahepatic bile ducts running parallel (arrowheads) and reuniting into a common channel (dotted arrow) at the level of the head of the pancreas consistent with type Va double common bile duct. In addition, a filling-defect suggestive of an obstructive calculus is seen in the common channel just above the ampulla (arrow). The cystic duct is inserting into the right-sided bile duct

DISCUSSION

Bile duct duplication although a normal feature in reptiles, fish, and birds, is considered a rare congenital anomaly of the adult human biliary system. The presence of double bile duct is a normal step during early human embryogenesis; however, this primitive duplicated system regresses to give rise to the conventional anatomy consisting of a solitary common bile duct. Duplication of the common bile duct was first reported in 1543 by Vesarius and until 1986 a mere 24 cases were reported in the Western Literature.[6]

The embryonic development of the liver, gallbladder system, and biliary tree starts around the third week of gestation. Initially, hepatic diverticulum is formed as an outgrowth of the endodermis in the distal part of the anterior intestine. This hepatic diverticulum divides into a ventral and dorsal bud as it grows and penetrates the mesenchyma of the ventral mesogastrium. Ventral bud, also known as pars cystica, forms the primitive gallbladder. The dorsal bud also known as pars hepatica divides to form the left and right liver lobes. As the liver and biliary tree develops inseparably, the stem of the hepatic primordium becomes the bile duct.[2] The definite lumen of the bile tree is developed by epithelial proliferation and vacuolization. As the vacuoles coalesce, they result in two parallel channels initially, both in the duodenum and the bile duct. The two channels in the bile ducts join separately, superior one to the dextral and inferior to the sinistral cavities of the duodenum. Of these the inferior opening gets suppressed and may sometimes be patent or blind ending.[7] Another important feature of the bile duct development is rotation of the primitive duodenum along its longer axis, which brings the duct superior to the second part of the duodenum. The anomalies can be ascribed to disturbances in recanalization of the hepatic primordium as well as coalescence of vacuoles of the primitive biliary duct, which has two lumens initially.[4]

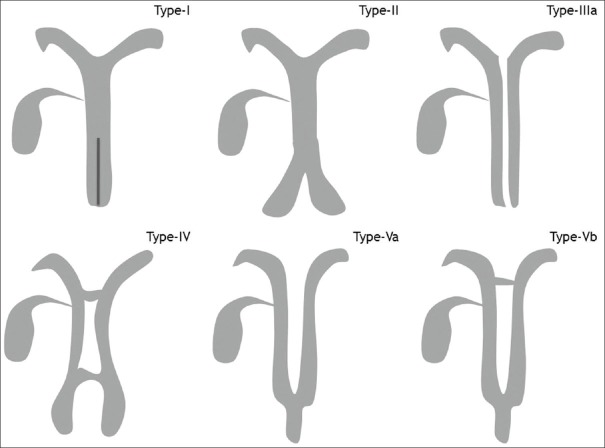

The earliest classification of double common bile duct (DCBD) was proposed by Goor and Ebert (1972) based on the anatomical appearance. The latest one is proposed by Choi et al. (2007) based on morphology, which adds on a new type V variant to the existing classification proposed by Saito et al. (1988).[8,9] These later classifications do not take into account where the aberrant CBD opens. As per the latest classification, description of various types of DCBD are [Figure 2]: Type I: Septum dividing the bile duct lumen; type II: Bifurcation of the distal bile duct and each channel draining independently into the bowel; type III: Duplicated extrahepatic bile ducts without (a) or with intrahepatic communicating channels (b); type IV: Duplicated extrahepatic bile duct with extrahepatic communicating channel or more than one communicating channels; and type-V refers to single biliary drainage of double bile ducts without (a) or with communicating channels (b).[9] The classification can be broadly seen as double drainage system in which there is an accessory bile duct opening into either duodenum, stomach, and a single drainage system in which the two separate biliary ducts fuse and open into duodenum through a single common channel or the accessory duct opens into the pancreatic duct and then joins the other bile duct forming a common single channel before opening into the duodenum. Boyden proposed that the development of type I DCBD was due to double vacuolization during the solid stage during the development of extrahepatic bile ducts, whereas chance elongation and early subdivision of the primitive hepatic furrow may be responsible for the other types of DCBD.[10,11]

Figure 2.

Modified double common bile duct classification proposed by Choi et al. Type I, septum dividing the bile duct lumen; type II, the distal bile duct bifurcates and each channel drains independently; type III, double bile ducts without (a) or with intrahepatic communicating channels (b); type IV, double bile duct with extrahepatic communicating channel(s); and type V, single biliary drainage of double bile ducts without (a) or with communicating channels (b)

Very limited data is available on this rare anomaly. Literature review reveals that DCBD is most commonly reported from Asia, especially from Japan. Kanematsu et al. (1992) reviewed 56 cases reported worldwide.[12] Yamashitha et al. reviewed 46 cases from Japanese literature,[6] whereas Gengchen et al. reviewed 24 cases from Chinese literature.[3] The greater incidence of the cases in this region might be related to the ethnicity. Yamashita et al. divided the cases as per Goor and Ebert based on the opening of the accessory duct.[6] In this study subtype I of the Saito et al.[8] classification, that is CBD with a septum dividing its lumen, is classified as the septal group. This group also included double common bile duct that rejoined as a single duct and opens into the duodenum at the normal site.[6] Later, this subtype is further classified as type V by Choi et al.[9] As the CBD opens normally into the duodenum in this group, there is minimal associated risk of abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction and thereby the risk of biliary or duodenal malignancy.[6] There is preponderance of type I cases (58.5%) in the Chinese series, whereas it is not so in the series reviewed by either Kanematsu et al. (3.6%) or Yamashitha et al. (8.5%).[6,12] The basis for this phenomenon is not clear. Our case is a type Va variant in which there is duplication of extrahepatic bile ducts opening into the short common CBD, which in turn opened into the duodenum. There is no anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction (APBJ), but it is complicated by cholelithiasis. There was a stone impacted in common bile duct at the site of opening into the duodenum. The cystic duct is seen to open into the right common duct. Since this is an incomplete duplication, there is a consensus that the disruptive event that results in this variant may have occurred at a later phase of embryogenesis.[3] Only two cases of type Va DCBD have been reported in the literature to our knowledge.[13] Our case is the third reported of this least common variety.

Knowledge of this aberrant biliary anatomy is needed preoperatively as this helps to prevent accidental ductal injuries. The accessory duct can be confused for cystic duct and its ligation leads to biliary obstruction. There is increased recognition of these conditions preoperatively by MRCP. Single shot half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo (HASTE) sequenced and multislice 3D images are now able to clearly depict the anatomy analogous to the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).[3] We were able to recognize the variant prior to ERCP and thereby the management was planned on this basis.

Double common bile duct is associated with choledochal cyst, biliary atresia, and abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction. Cholelithiasis, cholangitis, pancreatitis, and cholangiocarcinoma can complicate this anomaly.[13] It is imperative to note the site of opening of the accessory biliary duct as this heralds biliary and pancreatic reflux with chronic irritation and is associated with the site-specific malignancies as gastric, duodenal, and gall bladder malignancies.

Double common duct has been associated with high incidence of concomitant abnormal pancreaticobiliary union, especially if the accessory duct opens into pancreatic duct or duodenum.[9] It is more commonly seen in children as it presents early in life due to abdominal pain and other associated symptoms.[10] Patients with ABPJ may invariably require surgery in the form of separation of the biliary and pancreatic systems to prevent the reflux of pancreatic juice as well as excision of the extrahepatic ducts, which are at risk of malignancy. It is important to know whether ABPJ is associated with the double common CBD.

In conclusion, an extremely rare variant, type Va, of the double common bile duct complicated by choledocholithiasis has been reported on MRCP. Preoperative and pre-ERCP detection has helped to avert intraprocedural complications in the management of the patient. Knowledge of this rare anomaly is also important as it is associated with ABPJ, choledochal cyst, and is occasionally complicated by cholelithiasis and malignancy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Catalano OA, Singh AH, Uppot RN, Hahn PF, Ferrone CR, Sahani DV. Vascular and biliary variants in the liver: Implications for liver surgery. Radiographics. 2008;28:359–78. doi: 10.1148/rg.282075099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta V, Chandra A. Duplication of the extrahepatic bile duct. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2012;52:176–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2011.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen G, Wang H, Zhang L, Li Z, Bie P. Double common bile duct with choledochal cyst and cholelithiasis: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2014;44:778–82. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0561-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SW, Park do H, Shin HC, Kim IY, Park SH, Jung EJ, et al. Duplication of the extrahepatic bile duct in association with choledocholithiasis as depicted by MDCT. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9:550–4. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2008.9.6.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park MS, Kim BC, Kim Ti, Kim MJ, Kim KW. Double common bile duct: Curved-planar reformatted computed tomography (CT) and gadobenate dimeglumine-enhanced MR cholangiography. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27:209–11. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashita K, Oka Y, Urakami A, Iwamoto S, Tsunoda T, Eto T. Double common bile duct: A case report and a review of the Japanese literature. Surgery. 2002;131:676–81. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.124025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ando H. Embryology of the biliary tract. Dig Surg. 2010;27:87–9. doi: 10.1159/000286463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito N, Nakano A, Arase M, Hiraoka T. A case of duplication of the common bile duct with anomaly of the intrahepatic bile duct. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1988;89:1296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi E, Byun JH, Park BJ, Lee MG. Duplication of the extrahepatic bile duct with anomalous union of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system revealed by MR cholangiopancreatography. Br J Radiol. 2007;80:E150–4. doi: 10.1259/bjr/50929809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tahara K, Ishimaru Y, Fujino J, Suzuki M, Hatanaka M, Igarashi A, et al. Association of extrahepatic bile duct duplication with pancreaticobiliary maljunction and congenital biliary dilatation in children: A case report and literature review. Surg Today. 2013;43:800–5. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyden EA. The problem of the double ductus choledochus (an interpretation of an accessory bile duct found attached to the pars superior to the duodenum) Anat Rec. 1933;55:71–91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanematsu M, Imaeda T, Seki M, Goto H, Doi H, Shimokawa K. Accessory bile duct draining into stomach: Case report and review. Gastrointest Radiol. 1992;17:27–30. doi: 10.1007/BF01888503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Djuranovic SP, Ugljesic MB, Mijalkovic NS, Korneti VA, Kovacevic NV, Alempijevic TM, et al. Double common bile duct: A case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3770–2. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]