Abstract

Study Objectives:

To identify risk factors for experiencing nightmares among the Finnish general adult population. The study aimed to both test whether previously reported correlates of frequent nightmares could be reproduced in a large population sample and to explore previously unreported associations.

Design:

Two independent cross-sectional population surveys of the National FINRISK Study.

Setting:

Age- and sex-stratified random samples of the Finnish population in 2007 and 2012.

Participants:

A total of 13,922 participants (6,515 men and 7,407 women) aged 25–74 y.

Interventions:

N/A.

Measurements and results:

Nightmare frequency as well as several items related to socioeconomic status, sleep, mental well-being, life satisfaction, alcohol use, medication, and physical well-being were recorded with a questionnaire. In multinomial logistic regression analysis, a depression-related negative attitude toward the self (odds ratio [OR] 1.32 per 1-point increase), insomnia (OR 6.90), and exhaustion and fatigue (OR 6.86) were the strongest risk factors for experiencing frequent nightmares (P < 0.001 for all). Sex, age, a self-reported impaired ability to work, low life satisfaction, the use of antidepressants or hypnotics, and frequent heavy use of alcohol were also strongly associated with frequent nightmares (P < 0.001 for all).

Conclusions:

Symptoms of depression and insomnia were the strongest predictors of frequent nightmares in this dataset. Additionally, a wide variety of factors related to psychological and physical well-being were associated with nightmare frequency with modest effect sizes. Hence, nightmare frequency appears to have a strong connection with sleep and mood problems, but is also associated with a variety of measures of psychological and physical well-being.

Citation:

Sandman N, Valli K, Kronholm E, Revonsuo A, Laatikainen T, Paunio T. Nightmares: risk factors among the finnish general adult population. SLEEP 2015;38(4):507–514.

Keywords: adult, epidemiology, depression, dreaming, insomnia, nightmare, risk factor

INTRODUCTION

Nightmares are vivid dreams containing intense negative emotions that can result in the dreamer awakening from sleep.1,2 There is no universally accepted definition of a nightmare,3–7 and studies on nightmares therefore tend to have disparate ways of defining the phenomenon under investigation. Regardless, population-level studies have mostly produced comparable results concerning the prevalence and correlates of nightmares, even when using different questions and definitions to measure them.

Among the general adult population, nightmares are not uncommon: 2–6% of adults report frequent nightmares (typically defined as one or more per week), and 35–45% report at least one nightmare per month.8–13 Women have consistently been found to report more nightmares than men, with the sex difference being largest among young adults.8,14,15 Most studies have also reported an age effect, i.e., that nightmares are most prevalent among children and adolescents,16,17 whereas among adults they become more common with advancing age.8,15 Nightmare prevalence is also elevated among populations with a high probability of having been exposed to traumatic events, such as war veterans.8

Several prior studies have shown that frequent nightmares are associated with a variety of mental disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders as well as psychotic symptoms.9,10,18–21 Repeated posttraumatic nightmares are also one of the defining symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder,1,22 and frequent nightmares constitute an independent risk factor for attempted as well as completed suicide.19,23–25

Nightmares often co-occur with other sleep problems, especially insomnia9,17,19,20 and related symptoms of daytime fatigue.9,19 Their frequency is also affected by sleep duration independently of insomnia symptoms. In a study on nightmare prevalence in adolescents,17 it was found that nightmares were more common among those who slept more than 9 h or less than 7 h per night compared with those who slept 7–9 h. In addition to sleep duration, nightmares are also associated with the evening chronotype, at least in women.26,27

Medication that affects the structure of rapid eye movement-nonrapid eye movement (REM-NREM) cycles may induce nightmares in some users.28 Widely prescribed drugs of this kind include beta-blockers and some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Ethanol also has REM sleep-suppressing properties, and alcohol use and especially withdrawal may consequently cause nightmares in some individuals.28,29 A connection between nightmare frequency and a low socioeconomic status has also been observed in some studies,9,20 while being absent in others.13

Certain personality traits may be risk factors for nightmares, but large empirical studies on the topic are scarce. Hartmann has proposed that having a thin-boundary personality type that is characterized by a vivid imagination and openness to experiences makes a person more vulnerable to nightmares.30 More recently, Nielsen and Levin have proposed a neurocognitive model of nightmare etiology,14,31 in which they argue that a common denominator for many different correlates of nightmares is a “personality style characterized by intense reactive emotional distress”.

The current study explored the risk factors for nightmares in a large representative population-based sample of Finnish adults. Our aim was to test whether the associations between nightmares and various risk factors identified by previous research could be replicated in a representative population-based sample as well as investigate several previously unexplored risk factors. Our comprehensive dataset enabled us not only to test these associations, but to compare the magnitude of effect sizes of different correlates to determine whether they are minor or major risk factors for frequent nightmares. This has not been possible in prior studies, in which fewer predictor variables have simultaneously been available.

METHODS

The FINRISK Study

The National FINRISK Study is a series of health surveys of the Finnish general adult population conducted every 5 y since 1972. The surveys include a questionnaire that is mailed to the participants and a health examination at the local primary healthcare center, where the completed questionnaire is returned and checked by a nurse. In the current study, data from the FINRISK surveys of 2007 and 2012 were used. These surveys were chosen because they included the most comprehensive array of questions about sleep and mental health, many of which were absent from older surveys. In addition, these surveys did not include veterans of World War II who were present in earlier surveys. The presence of war veterans is known to elevate nightmare prevalence at the population level.8

The survey participants were randomly drawn from population registers of the study regions according to standardized procedures. In 2007, 12,000 people were invited to participate, with the final response rate being 67%. In 2012, 10,000 people were invited and 65% of them participated. Because both samples were randomly drawn, 42 participants (0.3%) answered both surveys by chance. These participants did not receive any special treatment in the analysis. Additional information on the sampling and the FINRISK study can be found on the Epidemiological and Clinical Finnish Sample Collections web-site.32 The FINRISK surveys of 2007 and 2012 received approval from the Coordinating Ethical Committee of Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District, and written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Participants

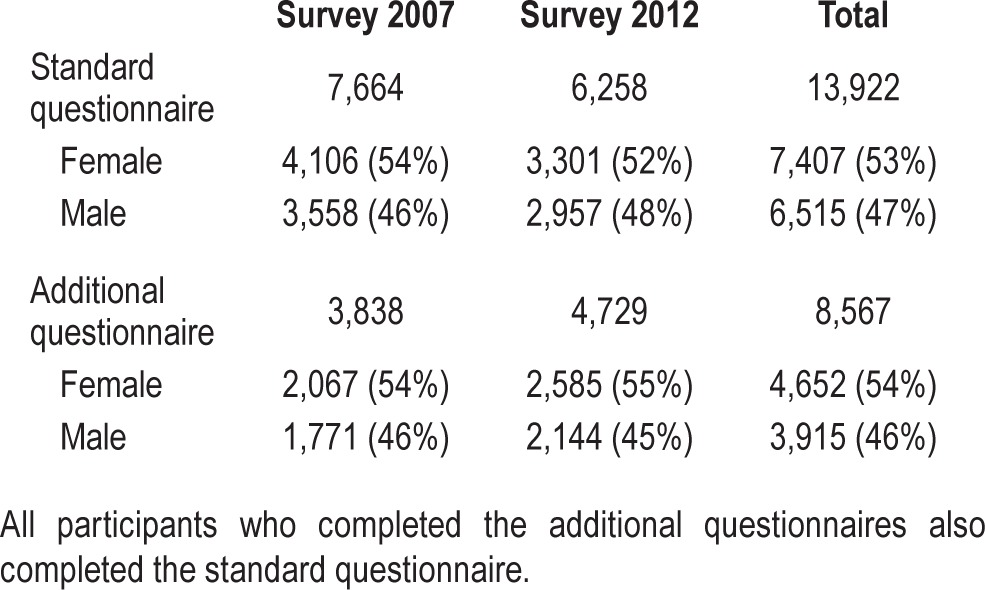

Combined, the surveys of 2007 and 2012 included 13,922 participants, of whom 53% were female. The age range of participants was 25–74 y (standard deviation 14.05, mean 50.92, median 52). In both surveys, all the participants received a standard FINRISK questionnaire, and some participants also received additional questionnaires. In 2007, 67% of participants received an additional questionnaire containing variables of interest, and in 2012, those who participated in the physical examination were given an additional questionnaire to be completed at home. The return rate of this questionnaire was 86%. The exact number of participants completing each questionnaire is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The number of participants in each survey.

The Questionnaire Items

The questionnaire item about nightmares in the FINRISK surveys is as follows: “During the past 30 days, have you had nightmares”, with the response options “often; sometimes; never”. No definition of a nightmare is provided to the participants.

We analyzed the association between the response to the nightmare question and 60 other items. A complete list of these items can be found in the electronic supplement. Some of the questions of interest were only present in the subsamples of the surveys, or only in one of the surveys, so N for single items varies from 3,838 to 13,922.

In addition to single items, the association of four instruments with nightmares was investigated. These included a Finnish translation of the 13-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-SF-13), a Finnish translation of the short Cynical Distrust Scale (CynDis), a part of the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ), and a Finnish translation of the shortened Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ).

The BDI-13 used in the FINRISK surveys includes items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, and 18 of the original BDI-21. The BDI-13 has been found to be an effective screening tool for depression among adults.33,34 For some analyses, the BDI scores were categorized to mild (5–7), moderate (8–15), and severe (over 16) depressive symptoms.34 In our data, the BDI-13 was included in the additional questionnaires of both surveys. It yielded a Cronbach alpha of 0.86 and 0.87 in the 2007 and 2012 survey, respectively.

The CynDis scale is a shortened version of the Cook-Medley hostility scale35 that has been found in factor analysis to have high internal consistency. It includes eight items consisting of statements such as “Nobody really cares what happens to others” and “It is safer not to trust anybody”, with response options on a four-point Likert scale. Higher scores on the scale mean that the person is more trusting. The CynDis was only included in the standard questionnaire of the FINRISK survey of 2007, and in that dataset it yielded a Cronbach alpha of 0.85.

The part of the JCQ used in the FINRISK surveys includes three questions about job demands (JCQ category 2) and three questions about job control (JCQ category 1b), which are the most important dimensions of work-related stress according to the Karasek demand/control model.36,37 The JCQ was part of the standard questionnaire in 2007 and included in the additional questionnaire in 2012. In the survey of 2007, Cronbach alpha of the job control category was 0.79 and that of the job demand category 0.78, whereas in the 2012 survey the corresponding values were 0.82 and 0.78, respectively.

The MEQ38 is a widely used questionnaire for self-determining the chronotype. The original MEQ was validated by measurements of circadian variation in the oral temperature. The FINRISK surveys include items 4, 5, 9, 15, 17, and 19 of the original MEQ. The MEQ was a part of the standard questionnaire in the 2007 survey and the additional questionnaire in the 2012 survey.

Statistical Methods

For the analysis of single associations we conducted Pearson chi-square (χ2) tests for categorical and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. It should be noted that most of the continuous variables tested were not normally distributed and were resistant to log transformation (BDI-13, CynDis, Life satisfaction), but because of the large sample size and the robustness of ANOVA parametric testing, the method was considered appropriate. Cramer V was used as a measure of the effect sizes for categorical variables and eta squared (η2) for the continuous variables. The scale of these effect size measures is different: For Cramer V, 0.1 is considered a small but meaningful association, and for eta squared, 0.01 constitutes a meaningful level. To correct for the increased possibility of falsely positive results because of multiple hypothesis testing in the same data, we chose 0.001 as the level of statistical significance for the testing of single associations.

Confirmatory factor analysis with maximum likelihood extraction and varimax rotation was used to split the BDI-13 into components for some analyses, and multinomial logistic regression was used for multivariable modeling. The alpha level of 0.01 was used during the multivariate analysis. The analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows version 21 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

RESULTS

Overall, 3.9% of the participants reported having had frequent nightmares during the previous 30 days, whereas 45.5% reported having had nightmares occasionally, and 50.6% reported no nightmares at all. There was no statistically significant difference between the surveys of 2007 and 2012 in nightmare prevalence (χ2(2, n = 13,922) = 3.56, P = 0.167), and the data from the surveys were therefore pooled in subsequent analyses.

Sociodemographic Factors

The sociodemographic factors most strongly associated with nightmare frequency were sex and employment status. Women had more nightmares than men: 4.8% of women and 2.9% of men reported frequent nightmares (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.102). Nightmare prevalence increased statistically significantly with advancing age among men (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V 0.076), but remained stable in women. More detailed analyses of the association between age, sex, and nightmares in these data are discussed in Sandman et al.8 Frequent nightmares were more common among unemployed and retired participants (6.0–7.1%) than the employed and students (2.7–3.9%). The effect size of this association was larger among men than women (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.101 for men and 0.065 for women).

A higher body mass index, lower education level, lower household income, and smaller household size were all associated with increase in nightmare frequency (χ2, P < 0.001). Marital status was associated with nightmares among men, with divorced or widowed men reporting frequent nightmares more often (5.5%) than men who were single or in a relationship (2.6–2.8%). This association was not found among women. However, the effect sizes of all these associations were very small (Cramer V, 0.2–0.8). There was no significant association between nightmares and being pregnant (χ2, P = 0.210). Full analyses can be found in Table S1 (supplemental material).

Sleep Related Factors

Insomnia was the single strongest correlate of nightmares (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.240). Of participants who reported frequent insomnia, 17.1% also reported frequent nightmares, whereas only 1.3% of participants without insomnia symptoms reported frequent nightmares. Dissatisfaction with the amount of sleep (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V 0.098), feeling exhausted (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.208), and having frequent headaches (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.172) were also strongly associated with nightmares.

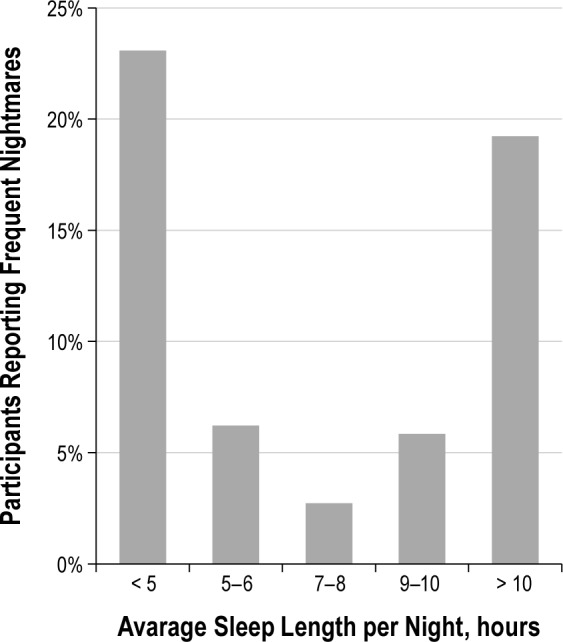

Sleep duration had a clear U-shaped association with nightmare frequency, as can be seen from Figure 1, but the effect size of this association was small (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.070). The evening chronotype was associated with nightmares in women: 7.5% of female evening types reported frequent nightmares compared with only 2.7% reported by female morning types (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V 0.067) but the effect size of this association was small. There was no significant association between nightmares and chronotype among men. Finally, those participants who reported having moderate to serious problems with changes in mood and sleeping patterns because of seasonal variation (in light) reported significantly more nightmares than those who did not have such problems (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.205). Full analyses can be found in Table S2 (supplemental material).

Figure 1.

The association between sleep duration and nightmare frequency is U-shaped. N = 13,708.

Psychological Well-Being

Depressive symptoms measured by the categorized BDI-13 (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.211) and the self-report of having received a depression diagnosis from a doctor (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.212) were strongly associated with frequent nightmares. Of the participants who had severe depressive symptoms (BDI score over 16), 28.4% reported frequent nightmares. Among those who had no depressive symptoms (BDI score < 5), the respective figure was 1.6%. A self-reported diagnosis of any other mental disorder (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.093) had a weaker but still significant association with nightmare frequency, as did the self-reported working ability of the participant (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.137). Exact figures can be found in Table S3 (supplemental material).

Continuous BDI scores were associated with nightmares with large effect size (F, P < 0.001; η2, 0.090), with frequent nightmare sufferers having higher BDI scores. The association between cynical distrust scale and nightmares had small effect size (F, P < 0.001; η2, 0.030) with frequent nightmare sufferers having lower scores that represent less trusting personality.

JCQ job control and job demand scores had significant associations with nightmare frequency, with a larger effect size among women (control: P < 0.001, η2 0.011; demand: P < 0.001, η2 0.010) than men (control: P < 0.001, η2 0.006; demand: P < 0.001, η2 0.008), but the effect sizes and post hoc tests imply that this association was weak. Full analyses of continuous variables can be found in Tables S9–S11 (supplemental material).

To further investigate the connection between the BDI score and nightmares, we performed explorative common factor analysis with maximum likelihood extraction and varimax rotation on the BDI and extracted three factors: a negative attitude toward self, lowered mood, and performance impairment.

Factor 1 consisted of questions 3, 5, 6, 7, and 10 of the BDI-13, which measure negative attitude toward self. It had an initial eigenvalue of 5.12, and after rotation explained 17.15% of the variance. Factor 2 included questions 1, 2, and 6, which measure lowered mood. Its eigenvalue was 1.14 and it explained 12.78% of the variance. Factor 3 included questions 8, 9, 11, 12, and 13, measuring daily performance impairment. It had an initial eigenvalue of 0.90 and explained 12.16% of the variance. The performance impairment factor includes questions concerning working ability and exhaustion that are also measured with other similar questions in the FINRISK questionnaire. The three-factor solution is theoretically justifiable and has previously been reported.39 Factor loadings can be found in Table S13 (supplemental material).

A multinomial regression model only including the three BDI factors revealed that they all associate similarly with nightmares: For a one-point increase in factor scores, the OR of experiencing frequent nightmares increases by 1.22 for a negative attitude toward self, 1.25 for lowered mood, and 1.40 for performance impairment (P < 0.0001 for all).

Life Satisfaction

Quality of life was investigated in the questionnaire with a self-report scale from 1 to 10, with 1 being the worst possible and 10 the best possible quality. The mean quality of life score was 5.98 among those with frequent nightmares and 7.80 among those with no nightmares. The population mean of 7.51 was higher than the mean for frequent nightmare sufferers and lower than the mean for those without nightmares. The difference was significant, with a medium effect size (F, P < 0.001; η2, 0.062). Full analyses can be found in Table S12 (supplemental material).

Satisfaction with different life domains was also associated with nightmares. Both dissatisfaction with the financial situation (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V 0.100) and achievements in life (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.121) were strongly associated with frequent nightmares. Dissatisfaction with family life was significantly associated with nightmares in both sexes, but the effect size of the association was larger among women. Among participants who were very unsatisfied with their family life, 31.5% of women (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.119) and 7.0% of men (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.090 reported frequent nightmares. For exact figures, see Table S4 (supplemental material).

Alcohol Consumption and Smoking

Question “Have you consumed alcohol during the past 12 mo” did not have statistically significant association to nightmares. The amount of alcohol consumed during the previous week had a statistically significant association, but the effect size was very small (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.060 among men and χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.046 among women).

The frequency of being intoxicated during the previous 12 mo had a significant association with nightmares: those who reported having been intoxicated several times a week reported more nightmares than participants who reported being intoxicated less frequently. The effect size of this association was larger among men (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.107) than among women (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.090).

Among men, there was also a significant association between smoking and frequent nightmares, but the effect size was very small (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.058). There was no statistically significant association between nightmares and smoking among women or the number of cigarettes smoked per day for either sex. Full analyses can be found in Table S5 (supplemental material).

Medication

The use of various medicines was significantly associated with frequent nightmares. Participants who had used pain-killers during the previous month reported more nightmares than those who had not. The association was strongest for painkillers used for joint and muscle pain (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.108) and weakest for those used to treat headaches (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.072). The use of sedatives (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.137), hypnotics (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.151), and antidepressants (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.151) was also strongly associated with having frequent nightmares.

The use of asthma medication, allergy medication, acetylsalicylic acid for heart attack prevention, anticoagulants, or antibiotics had no statistically significant association with nightmare frequency, or the association had a very small effect size. For full analyses, see Table S6 (supplemental material).

Physical Well-Being

There was a strong association between nightmare frequency and self-estimated physical health: frequent nightmares were reported by 28.9% of those who considered their health to be poor or very poor, but only 0.7% of those with very good health (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.165). Moreover, compared with the population mean of 3.9%, the 0.7% reported by participants in very good health is considerably lower.

Of the diagnosed physical illnesses, hypertension (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.113 for men and 0.078 for women) and angina pectoris (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.105 for men and 0.063 for women) had a significant association with nightmares, with a larger effect size among men. Heart failure, asthma, back illness, diabetes, and other joint disease than rheumatoid arthritis had statistically significant connections with nightmares, but the effect sizes were very small. Cancer, cholecystitis, and rheumatoid arthritis were not significantly associated with nightmare frequency. Full analyses can be found in Table S7 (supplemental material).

Of the variables measuring physical condition and the amount of exercise, the self-estimated physical condition had a strong connection with nightmare frequency that was very similar to the association of self-estimated health: Participants who were in poor condition reported more frequent nightmares (19%), and participants in excellent condition reported less frequent nightmares (1.5%) than the population average (3.9%) (χ2, P < 0.001; Cramer V, 0.121). The nature of work-related physical activity, the nature of leisure-time physical activity, the frequency of exercise, and the typical duration of exercise had a statistically significant association with nightmare frequency, but their effect sizes were very small. For full analyses, see Table S8 (supplemental material).

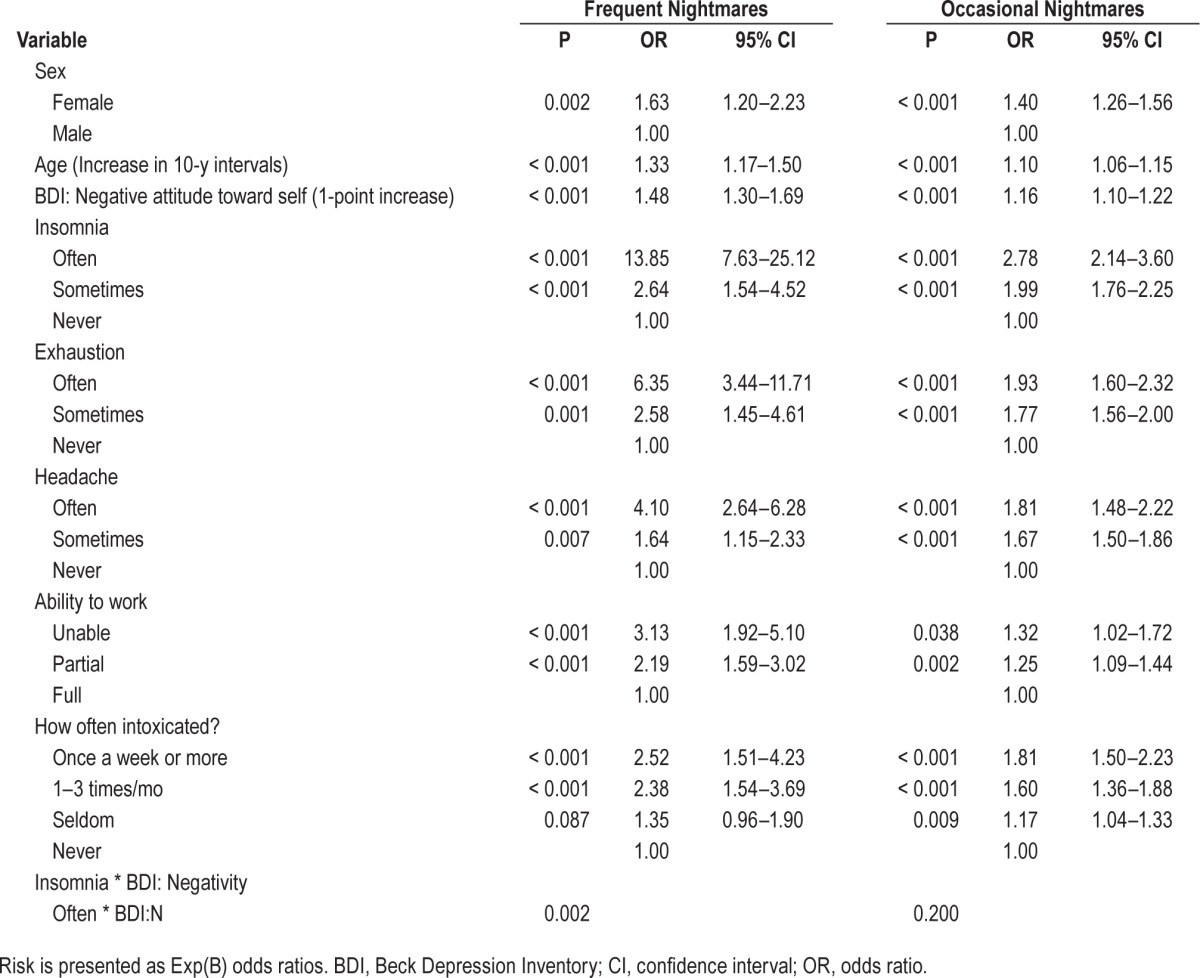

Multivariable Analysis

The multinomial logistic regression model of risk factors for nightmares is presented in Table 2. The model was constructed by starting with the 22 variables (see Table S14, supplemental material) that had the strongest association with nightmares in these data according to the effect size. To find the model best fitting these data, two methods were used: a model was first constructed by manually adding variables to the model based on their hypothesized importance and eliminating variables that became statistically nonsignificant during the process. Afterward, a second model was constructed by the automatic stepwise process in SPSS. Both methods produced the same final model that contained eight variables. To include BDI to the model, only data from additional questionaires of both surveys could be used resulting in n = 7,575.

Table 2.

The multinomial logistic regression model.

Instead of using the entire BDI-13 in the modeling, we separately tested different BDI factors. This method was beneficial because it minimized the overlap between certain BDI questions and other variables entered into the model, e.g., questions about insomnia symptoms and working ability. Only a negative attitude toward self remained an independent risk factor in the regression model after adding other variables.

Independent risk factors for nightmares in the final model were sex, age, the BDI factor ‘negative attitude toward self’, insomnia, feeling exhausted, headaches, the ability to work, and the frequency of being intoxicated. In addition to these, all two-way interactions between the predictor variables in the regression model were tested. Only the interaction between frequent insomnia and the BDI factor ‘negative attitude toward self’ was statistically significant and was included in the model. Overall, the model was statistically significant (χ2(32, n = 7,575) = 1,472.89, P < 0.0001), had a Nagelkerke statistic of 0.217, and correctly classified 62.6% of the observations (with the chance level being 33.3%).

It should be noted that although the nature of the data would in principle allow the interpretation of ORs as a relative risk,40 this was not possible because the direction of causality between nightmares and predictor variables was not clear. As such, the ORs should in this case be used as effect size estimates only.

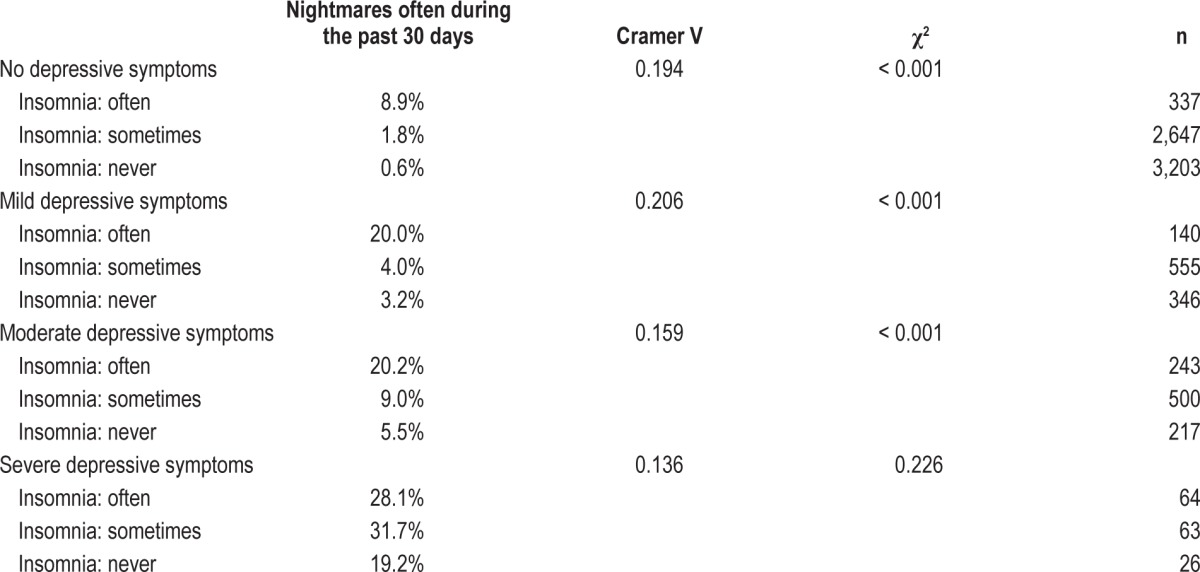

To interpret the interaction, additional analysis was conducted with the entire BDI-13, insomnia, and nightmares (Table 3). Among participants with moderate to no depressive symptoms, insomnia and nightmares had a significant linear association: an increase in insomnia symptoms was associated with an increase in nightmare frequency. However, among participants with severe depressive symptoms, there was no statistically significant association between nightmares and insomnia. Among participants with severe depressive symptoms, frequent nightmares were common regardless of whether participants had insomnia symptoms.

Table 3.

Association between nightmares and insomnia at different levels of categorized Beck Depression Inventory-13.

DISCUSSION

The strongest risk factors for frequent nightmares were depression and insomnia. However, among participants with severe depressive symptoms the association between nightmares and insomnia was not significant. A possible explanation for this pattern might be that frequent insomnia (41.8%) and nightmares (28.4%) are so common among participants with severe depressive symptoms that their association to each other can no longer be observed. In the regression analysis, we aimed to separate the insomnia-related component of the BDI from other symptoms of depression. A negative attitude toward self was the only component of the BDI that was not measured by any other question in the FINRISK survey, and accordingly, it was the only component of the BDI that remained as an independent risk factor for nightmares in the regression model. As such, a negative attitude toward self appears to be a part of depression that sets it apart from mood and sleep problems as a risk factor for nightmares.

The use of antidepressants and hypnotics was also strongly associated with frequent nightmares, but according to the regression model, their association with nightmares did not appear to be independent of the problems they aim to treat. The association between depression, insomnia, and nightmares is in line with several prior observations,9,10,18–20 although some studies have found that antidepressants and hypnotics had an independent effect on nightmares even when depression and insomnia symptoms were controlled for.25,41

Feeling exhausted and having frequent headaches were also strongly connected with nightmare frequency. They may represent the daytime consequences of insomnia, but the regression model implied that they were also independent risk factors for nightmares, an observation without a straightforward interpretation. The self-reported ability to work was a strong independent risk factor for frequent nightmares in our model. However, because there are a variety of reasons why people could lose their ability to work, including both psychological and physical problems, this association is quite unspecific. Female sex and advancing age were independent risk factors for nightmares as was expected in the light of prior studies, but unexpectedly, amount of alcohol consumed had a relatively weak association with nightmares. However, the frequency of intoxication appeared to be an independent risk factor for nightmares.

Several self-estimated quality-of-life measures were linearly associated with nightmares: low satisfaction was related to an increased and high satisfaction to a decreased risk of frequent nightmares. In regression analysis, these variables did not appear to be independent of depression, insomnia, or the self-reported ability to work.

Previously unreported associations with nightmares in these data included the use of painkillers, a cynical and distrusting personality, and seasonal variation in mood, sleep, and appetite. The use of painkillers may represent a connection between nightmares and chronic pain, as chronic pain is known to be associated with sleep disturbances.42–44 The association with seasonal variation could be interpreted to imply that nightmares may be part of the symptomatology of seasonal affective disorder, as is the case with common depression.

Short and long sleep duration,17 an evening chronotype among women,26,27 and a low socioeconomic status9,20 have been associated with frequent nightmares in prior studies. All these associations were replicated in these data. However, the effect sizes of these associations were very small compared with some of the other study variables, such as depression, insomnia, and life satisfaction. An association between an evening chronotype and nightmares was also reported by Merikanto et al.27 in a study that used data partially overlapping with the current study, namely FINRISK 2007 with 6,858 participants. In the current study, the association was replicated with a larger dataset of FINRISK 2007 and 2012 with 11,531 participants.

Finally, there were some interesting negative results: Women who were pregnant did not report statistically significantly more nightmares than those who were not pregnant, despite there being a known link between sleep quality, dreaming, and pregnancy.45,46 One possible explanation for the negative finding in our data could be that the dream disturbances related to pregnancy would only manifest themselves near the end of pregnancy.47 In the FINRISK questionnaire, it was only inquired whether the participant was pregnant without specifying the stage of pregnancy and therefore it is possible that there were not many late-stage pregnancies included in the sample. Another slightly surprising negative result was that smoking was not associated with nightmares, as smoking is known to be connected with poorer sleep quality.48

Because of the nature of our data, the study had several limitations. Nightmares were not defined for the participants, and as such it was impossible to distinguish between nightmares, which cause awakening, from bad dreams, which do not. Thus, we do not know whether the criteria used by some researchers to distinguish between nightmares and bad dreams apply to the phenomenon studied here.3,5,6 There is also a possibility that participants underestimated their nightmare frequency, as it has been shown that this often happens with retrospective questionnaires when compared with prospective dream logs.5 It is also regrettable that to minimize the variation between survey questions, it was not possible to use the FINRISK surveys from 1972 to 2002, and it would also have been interesting to be able to measure the anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms of the participants, but data did not include information on these symptoms.

Overall, these data revealed a few major risk factors for frequent nightmares and produced a large number of significant associations with smaller effect sizes. The common denominator for all these risk factors, possibly excluding frequent intoxication, appears to be lowered psychological or physical well-being. As such, there does not appear to be a single leading risk factor for having frequent nightmares, but rather, frequent nightmares are related to lowered mood, sleep quality, and well-being, which may be caused by various factors.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This work received financial support from several nonprofit organizations: Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation to Nils Sandman; Finnish National Doctoral Programme of Psychology to Nils Sandman; Sigrid Juselius Foundation to Tiina Paunio; University of Helsinki (EVO) TYH2010306 (to Tiina Paunio); Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS) to Katja Valli; and Academy of Finland (Project 266434) to Katja Valli and Antti Revonsuo. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. This study was performed at the University of Turku, Turku, Finland and at the National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr Jouko Katajisto for statistical consultation and Milla Karvonen for proofreading the manuscript, as well as three anonymous reviewers for helping to improve the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Analyses of Categorical Variables (Tables S1–S8)

Sociodemographic factors.

Sleep related factors.

Psychological well-being.

Life satisfaction.

Alcohol consumption and smoking.

Medication.

Physical well-being.

Physical exercise.

Analyses of Continuous Variables (Tables S9–S12)

Full analyses of continuous variables with ANOVA can be found in these tables.

Beck Depression Inventory-13.

Job content questionnaire.

Cynical distrust scale.

Quality of life.

Factor solution for the variance analyses.

Variables considered for multinomial regression analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 2nd ed. Westchester IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blagrove M, Farmer L, Williams E. The relationship of nightmare frequency and nightmare distress to well being. J Sleep Res. 2004;13:129–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blagrove M, Haywood S. Evaluating the awakening criterion in the definition of nightmares: how certain are people in judging whether a nightmare woke them up? J Sleep Res. 2006;15:117–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zadra A, Donderi D. Nightmares and bad dreams: their prevalence and relationship to well-being. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:273–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zadra A, Pilon M, Donderi DC. Variety and intensity of emotions in nightmares and bad dreams. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:249–54. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000207359.46223.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spoormaker VI, Schredl M, Bout Jvd. Nightmares: from anxiety symptom to sleep disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandman N, Valli K, Kronholm E, et al. Nightmares: prevalence among the Finnish General Adult Population and War Veterans during 1972-2007. Sleep. 2013;36:1041–50. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li SX, Zhang B, Li AM, Wing YK. Prevalence and correlates of frequent nightmares: a community-based 2-phase study. Sleep. 2010;33:774–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.6.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hublin C, Kaprio J, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M. Nightmares: familial aggregation and association with psychiatric disorders in a nationwide twin cohort. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88:329–36. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990820)88:4<329::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janson C, Gislason T, De Backer W, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances among young adults in the three European Countries. Sleep. 1995;18:589–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjorvatn B, Grønli J, Pallesen S. Prevalence of different parasomnias in the general population. Sleep Med. 2010;11:1031–4. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schredl M. Nightmare frequency and nightmare topics in a representative German sample. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260:565–70. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen T, Levin R. Nightmares: a new neurocognitive model. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:295–310. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schredl M, Reinhard I. Gender differences in nightmare frequency: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li SX, Yu MW, Lam SP, et al. Frequent nightmares in children: familial aggregation and associations with parent-reported behavioral and mood problems. Sleep. 2011;34:487–93. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.4.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munezawa T, Kaneita Y, Osaki Y, et al. Nightmare and sleep paralysis among Japanese adolescents: a nationwide representative survey. Sleep Med. 2011;12:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li SX, Lam SP, Chan JW, Yu MW, Wing YK. Residual sleep disturbances in patients remitted from major depressive disorder: a 4-year naturalistic follow-up study. Sleep. 2012;35:1153–61. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanskanen A, Tuomilehto J, Viinamäki H, Vartiainen E, Lehtonen J, Puska P. Nightmares as predictors of suicide. Sleep. 2001;24:845–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohayon MM, Morselli PL, Guilleminault C. Prevalence of nightmares and their relationship to psychopathology and daytime functioning in insomnia subjects. Sleep. 1997;20:340–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.5.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levin R, Fireman G. Nightmare prevalence, nightmare distress, and self-reported psychological disturbance. Sleep. 2002;25:205–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nemeroff CB, Bremner JD, Foa EB, Mayberg HS, North CS, Stein MB. Posttraumatic stress disorder: a state-of-the-science review. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sjöström N, Waern M, Hetta J. Nightmares and sleep disturbances in relation to suicidality in suicide attempters. Sleep. 2007;30:91–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pigeon WR, Pinquart M, Conner K. Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:e1160–7. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li SX, Lam SP, Yu MW, Zhang J, Wing YK. Nocturnal sleep disturbances as a predictor of suicide attempts among psychiatric outpatients: a clinical, epidemiologic, prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1440–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05661gry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen T. Nightmares associated with the eveningness chronotype. J Biol Rhythms. 2010;25:53–62. doi: 10.1177/0748730409351677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merikanto I, Kronholm E, Peltonen M, Laatikainen T, Lahti T, Partonen T. Relation of chronotype to sleep complaints in the general Finnish population. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29:311–7. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.655870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pagel J, Helfter P. Drug induced nightmares—an etiology based review. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:59–67. doi: 10.1002/hup.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roehrs T, Roth T. Sleep, sleepiness, sleep disorders and alcohol use and abuse. Sleep Med Rev. 2001;5:287–97. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartmann E. Dreams and nightmares: the origin and meaning of dreams. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin R, Nielsen TA. Disturbed dreaming, posttraumatic stress disorder, and affect distress: a review and neurocognitive model. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:482–528. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collections EaCFS. The National FINRISK Study. 2013. [cited 2014 28 February 2014]. Available from: http://www.nationalbiobanks.fi/index.php/studies2/7-finrisk.

- 33.Beck AT, Beamesderfer A. Assessment of depression: the depression inventory. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1974;7:151–69. doi: 10.1159/000395074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aalto AM, Elovainio M, Kivimäki M, Uutela A, Pirkola S. The Beck Depression Inventory and General Health Questionnaire as measures of depression in the general population: a validation study using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview as the gold standard. Psychiatry Res. 2012;197:163–71. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenglass ER, Julkunen J. Construct validity and sex differences in Cook-Medley hostility. Pers. Individ. Dif. 1989;10:209–18. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3:322–55. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Admin Sci Q. 1979;24:285–308. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horne JA, Ostberg O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol. 1976;4:97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viera AJ. Odds ratios and risk ratios: what's the difference and why does it matter? South Med J. 2008;101:730–4. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31817a7ee4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lam SP, Fong SY, Ho CK, Yu MW, Wing YK. Parasomnia among psychiatric outpatients: a clinical, epidemiologic, cross-sectional study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1374–82. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith MT, Haythornthwaite JA. How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? Insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:119–32. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raymond I, Nielsen TA, Lavigne G, Manzini C, Choinière M. Quality of sleep and its daily relationship to pain intensity in hospitalized adult burn patients. Pain. 2001;92:381–8. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finan PH, Smith MT. The comorbidity of insomnia, chronic pain, and depression: dopamine as a putative mechanism. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17:173–83. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lara-Carrasco J, Simard V, Saint-Onge K, Lamoureux-Tremblay V, Nielsen T. Disturbed dreaming during the third trimester of pregnancy. Sleep Med. 2014;15:694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nielsen T, Paquette T. Dream-associated behaviors affecting pregnant and postpartum women. Sleep. 2007;30:1162–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lara-Carrasco J, Simard V, Saint-Onge K, Lamoureux-Tremblay V, Nielsen T. Disturbed dreaming during the third trimester of pregnancy. Sleep Med. 2014;15:694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang L, Samet J, Caffo B, Punjabi NM. Cigarette smoking and nocturnal sleep architecture. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:529–37. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sociodemographic factors.

Sleep related factors.

Psychological well-being.

Life satisfaction.

Alcohol consumption and smoking.

Medication.

Physical well-being.

Physical exercise.

Beck Depression Inventory-13.

Job content questionnaire.

Cynical distrust scale.

Quality of life.

Factor solution for the variance analyses.

Variables considered for multinomial regression analyses.