Abstract

To test the hypothesis that self-compassion buffers people against the emotional impact of illness and is associated with medical adherence, 187 HIV-infected individuals completed a measure of self-compassion and answered questions about their emotional and behavioral reactions to living with HIV. Self-compassion was related to better adjustment, including lower stress, anxiety, and shame. Participants higher in self-compassion were more likely to disclose their HIV status to others and indicated that shame had less of an effect on their willingness to practice safe sex and seek medical care. In general, self-compassion was associated with notably more adaptive reactions to having HIV.

Keywords: coping, HIV/AIDS, illness, self-compassion, shame

Living with a potentially life-threatening disease is a stressful and emotionally draining experience. Researchers have identified many variables—aspects of both people’s social environments and their personal dispositions—that are linked to how effectively they cope with medical problems. For example, social support, optimism, education, time since diagnosis, and knowledge about one’s disease are linked with positive coping (Carver et al., 1993; Maher and DeVries, 2011; Valldeoriola et al., 2010), whereas social conflict, shame, and perceived stigmatization are negatively associated with coping (Miles et al., 2007; Persons et al., 2010). Among HIV-infected people, family support, acceptance of HIV status, and religious beliefs contribute to health and well-being (Carvalho et al., 2007; Coleman, 2003). HIV treatment adherence, viewed as an indicator of effective coping, correlates positively with disease-related knowledge, treatment self-efficacy, and education level (Grierson et al., 2011; Pinheiro et al., 2002). The focus of this article is on a newly identified construct that offers particular promise as a buffer against the distress people experience when confronting serious illness.

Self-compassion is an orientation toward one’s problems that involves treating oneself with the same care and concern with which one treats loved ones when they experience difficulties in life. When they face problems, self-compassionate people treat themselves with kindness and concern rather than criticism or judgment, recognize that difficulties are a normal part of life, and approach their problems with equanimity and balance, neither downplaying nor over-identifying with their negative thoughts and feelings (Neff, 2003b).

Self-compassion is associated with well-being and resiliency. People who are high in self-compassion deal with negative events—including failure, rejection, and loss—more successfully than people who are low in self-compassion (see Neff, 2009). Self-compassion predicts adaptive emotional and cognitive reactions to both minor daily hassles and major life events, attenuates reactions to negative feedback, is associated with adaptive reactions to marital separation, and buffers people against negative feelings when thinking about distressing life events (Leary et al., 2007; Magnus, 2007; Neff et al., 2005, 2007a; Sbarra et al., 2012). Older people who are high in self-compassion cope better with the stresses of aging than those who are low (Allen et al., 2012). Not surprisingly, self-compassion is associated with indices of psychological well-being such as optimism, emotional stability, and life satisfaction. Studies also show that self-compassion bears a unique relationship to well-being that is independent of neuroticism, self-esteem, depression, and coping styles (Leary et al., 2007; Neff, 2003a; Neff et al., 2007a, 2007b; Neff and Vonk, 2009).

Evidence also indicates that self-compassion is associated with adaptive responses to illness. Terry and Leary (2011) suggested that self-compassion may promote health-related behaviors by lowering defensiveness, reducing negative emotions and self-derogation that compromise adaptive behaviors, and enhancing medical adherence out of a desire to treat oneself well. Thus, research into the link between self-compassion and reactions to medical problems provides a novel perspective on how people cope with chronic illness and offers ideas for innovative interventions that increase patients’ self-compassionate responses.

HIV is a particularly threatening and distressing illness. Not only does HIV carry the possibility of premature death, but the stigma associated with HIV creates special personal and social problems. Many people who contract HIV already confront substantial psychological and social challenges, including poverty, isolation, substance abuse, and mental health difficulties (Reisner et al., 2009; Safren et al., 2003). HIV diagnosis can exacerbate these burdens by adding concerns about stigmatization and discrimination, disclosure of HIV status, treatment access, and disease trajectory (Martin and Kagee, 2011), thereby compounding existing stress and increasing the risk for psychiatric disorders (Ciesla and Roberts, 2001; Martin and Kagee, 2011). Some people respond to learning that they are HIV-infected with anger, self-blame, depression, and even disgust, reactions that compromise their ability to accept their situation and take steps to deal with it. For example, people who blame themselves for contracting HIV often avoid dealing with their disease (Clement and Schönnesson, 1998). Thus, self-compassion, which forgoes blame and shame, should be beneficial for people who are HIV-infected.

A particularly important health behavior with which self-compassion may be associated is adherence to medical regimens (Terry and Leary, 2011). Nonacceptance, anger, and self-denigration may undermine adherence, and this might be particularly true for conditions for which people feel responsible or that are stigmatizing, as in the case of HIV (Brion and Menke, 2008). Feeling ashamed about a medical problem is associated with lower treatment adherence (Van Achterberg et al., 2008), and HIV-infected patients are often ashamed of their disease if not themselves (Persons et al., 2010). In fact, acceptance of being HIV-infected appears to be crucial for adherence to HIV treatment. Brion and Menke (2008) reported that patients who initially struggled with adherence indicated that they were not able to engage fully in treatment until they had accepted and “owned” their illness.

Just as other-directed compassion involves promoting the well-being of other people, self-compassion should be associated with treating oneself in caring ways, such as going for medical appointments and behaving in ways that promote one’s health. Research suggests that people who are higher in self-compassion seek medical treatment more quickly when they have symptoms of a medical problem (Terry et al., 2012) and are more willing to use medical aids, such as wheelchairs, when needed (Allen et al., 2012).

Virtually everyone initially responds to having a serious illness, such as HIV, with strong emotions. If unchecked because a person lacks self-compassion, negative reactions foster suffering, denial, avoidance, and an unwillingness to face the problem, leading to coping tactics that undermine treatment adherence. However, people who approach their diagnosis with self-compassion are more likely to accept their problem, treat themselves with concern and kindness, and maintain equanimity. Given that negative self-judgment and negative affect are associated with less self-care among medical patients (Cruess et al., 2007), self-compassion should promote positive self-views and adaptive responses.

The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between self-compassion and the emotional and behavioral reactions of people with HIV infection. We investigated three broad hypotheses suggesting that compared to people who are low in self-compassion, people who are high in self-compassion (1) cope better with HIV in terms of lower stress and negative affect, (2) behave in ways that encourage medical management of the disease (by searching for information, seeking treatment, and complying with medical regimens), and (3) deal more effectively with the interpersonal aspects of living with HIV (by feeling less ashamed and more freely disclosing their status to others). Because of sex differences in how HIV is typically contracted and in how men and women cope with aspects of being HIV-positive (Kennedy, 1995; Schlebusch and Govender, 2012) we also examined whether gender moderates the relationship between self-compassion and reactions to HIV.

Method

Participants

Participants were 187 HIV-infected individuals (121 men and 66 women) who were contacted through flyers and snowball sampling. Flyers, posted in the lobby areas of local HIV care providers and social service agencies, included a brief description of the study, inclusion criteria, and contact information (phone and e-mail). In addition to having HIV infection, inclusion criteria included being 18 years of age or older, currently taking antiretroviral therapy (ART), and the ability to speak and read English. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 70 (M = 45.9, SD = 8.28) and had been diagnosed with HIV between a few months and 27 years earlier, although most had been diagnosed within the past 5 years (M = 2.47, SD = 4.36).

Participants were predominately African-American (80.9%), with 12.8 percent White, 2.7 percent Hispanic, 2.1 percent Native American, and 1.6 percent other. These percentages roughly reflect the patient populations in the clinics from which the samples were drawn. Reported educational levels showed that 26.6 percent of the participants had not completed high school, 31.9 percent had completed high school or a General Equivalency Diploma, 22.9 percent had some college or technical training, 7.4 percent held a bachelor’s degree, 4.8 percent held an associate’s or technical degree, and 4.8 percent had a graduate degree. More than half of the participants (58.5%) were single, 22.3 percent were married or partnered, 12.8 percent were divorced or separated, and 6.4 percent were widowed.

Materials

The first section of the questionnaire assessed background and demographic information (sex, age, race and relationship status), medical background (date of diagnosis and date ART was initiated), and currently prescribed medications. Adherence to prescribed medical regimen was measured using the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) 4-day recall adherence measure—total doses taken divided by total doses prescribed (Chesney et al., 2000). Treatment adherence has been conceptualized and measured in a variety of ways, and no gold standard exists for measuring adherence. Self-report methods for assessing adherence to ART have been shown to provide as accurate a measure of adherence as other commonly used measures (Mannheimer et al., 2006; Pearson et al., 2007).

To assess participants’ reasons for not being adherent, they were asked how often in the past month they had missed taking their medications because they were away from home, were busy with other things, simply forgot, had too many pills to take, wanted to avoid side effects, did not want others to notice them taking medication, had a change in daily routine, felt that the drug was harmful or toxic, fell asleep or slept through dose time, felt sick or ill, felt depressed or overwhelmed, had problems taking the pills at specified times (e.g. with meals or on an empty stomach), ran out of pills, and felt good. Ratings were on a 4-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, and 4 = often).

Participants completed a modification of the Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, 2003a). Based on item analyses, Allen et al. (2012) selected the four items that loaded highest on each of the three factors in Neff’s original scale, thereby reducing the length of the scale from 26 to 12 items.1 The shortened scale correlated .91 with the original 26-item scale, and the item mean of the shortened scale was 3.68 (compared to 3.69 for the original scale in Study 1). Analyses showed that the internal reliability of the 12-item scale was acceptable (α > .80), the 12-item scale correlated .92 with the full-length scale, and the 12-item scale correlated with other psychometric measures at levels comparable to the original 26-item scale (Allen et al., 2012).

The remainder of the questionnaire assessed participants’ feelings, thoughts, and behaviors with respect to being HIV-infected. First, participants completed the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983), a 14-item measure of the degree to which people perceive situations in their lives as stressful. Participants rated how often they experienced each feeling or thought during the past month on a 5-point scale (1 = never; 5 = very often). The PSS has demonstrated strong evidence of reliability, validity, and efficacy in studies of the relationship between stress and disease.

Participants completed the Response to Illness Questionnaire (Pritchard, 1974), which assesses patients’ thoughts and feelings about their illness, including perceptions, explanations, and consequences of their illness; emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses; and effects of the illness on their relationships with other people.

Participants completed two subscales of the HIV and Abuse-Related Shame Inventory (HARSI; Neufeld et al., 2012). The HIV-Related Shame Subscale consists of 14 items that reflect feeling ashamed about being HIV-infected (e.g. feeling ashamed, putting oneself down, hiding infection from others, and feeling worthless). Respondents’ ratings (1 = not at all; 5 = very much) were summed to create an index of HIV-related shame. Neufeld et al. (2012) presented evidence regarding the scale’s psychometric properties.

A second 10-item subscale from the HARSI measures the impact of HIV-related shame on beneficial health-relevant behaviors such as using condoms, interacting with other people, applying for services, telling other people about one’s HIV status, and adhering to treatment. Because we were interested in how self-compassion relates to specific behaviors, the 10 items on this subscale were each treated as a separate outcome variable.

Procedure

People who contacted the research coordinator were given details of the study, screened for eligibility, and, if willing to participate, scheduled to come to the research site or were given a copy of the questionnaire to complete at home and return. A total of 150 participants completed the study at the Behavioral Research Laboratories at Duke University, and 38 took questionnaires home and returned them by mail.

Results

T-tests were conducted to compare scores on all measures for participants who completed the study at home versus those who came to the research laboratory. Of the 28 comparisons, only one was significant at the .05 level; all other ps > .10. Given that this rate of significance is less than would be expected on the basis of Type I error, we conclude that the two modes of completion did not affect participants’ responses.

The items on the 12-item Self-compassion Scale were sufficiently reliable (α = .82). Male and female participants’ scores on the brief Self-compassion Scale did not differ significantly, t(175) = .88, p = .38.

Unless otherwise indicated, data were analyzed using hierarchical multiple regression analyses in which self-compassion (mean centered), gender (dummy coded), and their product were used as predictors of the various outcome variables. Effects of self-compassion and gender were entered on Step 1 of each analysis to examine main effects, and their product was entered on Step 2 to test the two-way interaction after partialling out the main effects. Main effects of self-compassion were examined via semi-partial correlations that removed the influence of gender; main effects of gender were examined via means for men and women adjusted for the effects of self-compassion, and the interactions between gender and self-compassion were tested while partialling out the main effects of each. Significant interactions were decomposed by testing simple regression equations separately for men and women. Given the number of statistical tests, an alpha-level of .01 was used.

Stress during the past month

Because previous studies have revealed two weakly correlated factors in factor analyses of the PSS (Cohen and Williamson, 1988; Reis et al., 2010), the scale items were factor analyzed using a principal axes extraction and an oblique (direct oblimin) rotation. Based on inspection of the scree plot, two factors were retained; both factors had eigenvalues greater than 1.0, and the eigenvalue of the next largest factor was .94. The highest loading items on Factor 1 expressed success at dealing with stressful events during the past month (e.g. felt confident in ability to handle personal problems, effectively coped with important life changes), and Factor 2 involved items that expressed a high level of stress and an inability to cope adequately (e.g. felt nervous and stressed, felt unable to control important things in life). The two factors were not correlated (−.09, ns).

Two hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted using the factor scores as outcome variables and self-compassion, gender, and their interaction as predictors. Both analyses revealed a main effect of self-compassion but no effect of gender or interaction. For Factor 1, self-compassion significantly predicted lower stress and more successful coping within the past month, sr = .52, t(161) = 7.69, p < .001. Analysis of Factor 2 showed that higher self-compassion was negatively associated with stressful feelings and perceived inability to deal with stressful events, sr = −.52, t(161) = 7.72, p < .001.

Behavioral effects of shame about being infected with HIV

The HIV-related Shame Scale had an alpha coefficient of .92. A regression analysis showed that level of self-compassion significantly predicted the level of HIV-related shame that participants reported, sr = .49, t(161) = 7.32, p < .001. The main effect for gender and the self-compassion by gender interaction were not significant.

Participants rated the degree to which feelings of shame about having HIV influenced 10 health-relevant behaviors during the past month. As shown in Table 1, at the .01 level of significance, self-compassion significantly predicted five of the 10 behaviors. Specifically, participants who reported lower self-compassion reported that feelings of shame had a greater effect in keeping them from: disclosing HIV status to a needle-sharing partner or a coworker, getting needed medical or psychological care, adhering to HIV treatments, getting information or asking questions about HIV, and disclosing their HIV status to a friend or family member. (Three additional effects approached the .01 level of significance: wearing a condom or asking a partner to wear a condom, disclosing HIV status to a sex partner, and interacting with others infected with HIV, ps < .03.) Tests of gender differences revealed only one effect: women (M = 1.46) indicated that shameful feelings about HIV kept them from adhering to their HIV treatments more than men (M = 1.26), t(161) = 2.25, p = .02.

Table 1.

Correlations between self-compassion and behaviors

| sra | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wearing a condom or asking a partner to wear a condom | .17 | 2.23 | .027 |

| Disclosing HIV status to a sex partner | .18 | 2.33 | .021 |

| Disclosing HIV status to a needle partner or coworker | .23 | 2.87 | .005 |

| Getting needed medical or psychological care | .36 | 4.98 | .001 |

| Sticking to HIV treatments, keeping appointments, and taking medications on time | .25 | 3.48 | .001 |

| Getting information or asking questions about HIV | .24 | 3.32 | .001 |

| Interacting with others who are HIV positive | .18 | 2.44 | .016 |

| Disclosing their HIV status to a friend or family member | .22 | 2.89 | .004 |

| Applying for services, such as housing or disability | .13 | 1.75 | .08 |

| Cleaning needles or syringes before letting someone else use them | .00 | .05 | .96 |

Semi-partial correlation controls for gender.

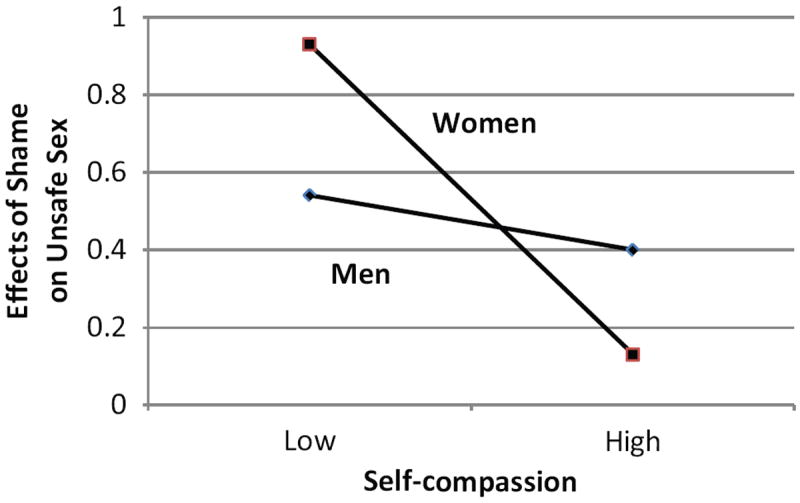

Although none of the two-way interactions between self-compassion and gender were significant at the .01 level, one effect at the .05 level should be mentioned. Specifically, an interaction was obtained on the degree to which shame led participants to wear a condom or ask a partner to wear a condom, sr = .15, t(161) = 2.03, p = .044. As shown in Figure 1, self-compassion was unrelated to condom use among men, t(110) = −.59, p = .56, but women who were lower in self-compassion were significantly more likely to indicate that shame kept them from asking their partner to use a condom, sr = −.36, t(58) = 2.96, p = .005.

Figure 1.

Effects of self-compassion and gender on failure to use condoms.

Perceptions of HIV as an illness

Participants rated their attitudes and reactions toward HIV on the 50 items from Pritchard’s (1974) study of dialysis patients. Because previous research has shown that the scale is multifactorial (Pritchard, 1974, 1977) and the factor structure of the items may differ between reactions to kidney failure versus HIV, we conducted a principal axis factor analysis on the items. The scree plot revealed 13 factors—12 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.00 and one factor with an eigenvalue of .997—so 13 factors were retained and rotated to a direct oblimin solution. Values for 13- factor scores were created by weighting each participant’s responses on the 50 items by the respective factor score coefficients to estimate participants’ scores on the 13 latent variables. The 13 factor scores were then analyzed in hierarchical multiple regression analyses in which self-compassion (mean centered), gender (dummy coded), and their product were used as predictors, with self-compassion and gender entered on Step 1 and the interaction term entered on Step 2.

No main effects of gender were obtained, but significant effects of self-compassion emerged on nine of the factors. Table 2 lists the 13 factors along with items that loaded most strongly on each. Compared to those who scored lower in self-compassion, participants who scored higher reported lower negative affect (Factor 1); viewed HIV as having certain positive consequences (Factor 2); were less ashamed and concerned about others learning that they were HIV-infected (Factor 5); felt less that they were personally responsible for being HIV-positive, deserved contracting HIV, or were being punished (Factor 6); reported feeling less that their illness was a private, unshared burden of which others were unaware (Factor 7); felt less defeated, uninformed, or dependent on others because of their HIV infection (Factor 8); catastrophized less (Factor 10); wanted to know more about the disease (Factor 11); and resisted the idea of being HIV-infected (Factor 12).

Table 2.

Self-compassion and reactions to HIV

| Factors and highest loading items | sr1 | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1—negative affect | −.57 | 7.34 | .001 |

| I feel anxious about it (.68) | |||

| I am worried that because of it I am not meeting my responsibilities as I should (.68) | |||

| I feel miserable about it (.40) | |||

| Factor 2—positive stressor | .26 | 3.12 | .002 |

| In some ways I have gained from it (.70) | |||

| I appreciate the help and sympathy it has brought me (.61) | |||

| I look on it as a challenge (.40) | |||

| I think of it as a problem to be solved (.37) | |||

| Factor 3—emotional distance | .12 | 1.32 | .172 |

| I put the thought of it out of my mind (.60) | |||

| I do not think there is any explanation on my part why it occurred (.57) | |||

| It is not as serious as other people think it is (.50) | |||

| I am not told enough about it (.46) | |||

| Factor 4—blame | −.22 | 2.59 | .011 |

| Others are to blame for it (.65) | |||

| Others are responsible for it (.65) | |||

| Factor 5—public shame | −.31 | 3.74 | .001 |

| I do not like others knowing about it (.92) | |||

| I want to keep the fact that I have it to myself (.81) | |||

| I am ashamed of it (.48) | |||

| Factor 6—personal blame | −.32 | 3.93 | .001 |

| I feel that it has something to do with me that it has occurred (.71) | |||

| I must have done something to deserve it (.65) | |||

| It is a punishment for something I have done (.57) | |||

| I am in some way responsible for it (.45) | |||

| Factor 7—private burden | −.27 | 3.17 | .002 |

| I think a good deal about it (.49) | |||

| I do not think others realize that because of it I cannot cope with responsibilities (.42) | |||

| Factor 8—resignation | −.29 | 3.51 | .001 |

| It defeats me (.51) | |||

| I resent the way it makes me dependent on others (.46) | |||

| I am not told enough about it (.43) | |||

| Factor 9—resistance | −.05 | .65 | .530 |

| I feel I have to resist it (.61) | |||

| Factor 10—catastrophizing | −.27 | 3.16 | .002 |

| I do not think I can resist it (.52) | |||

| It is worse than others realize (.35) | |||

| Factor 11—ego-protecting avoidance | −.26 | 3.10 | .002 |

| I do not want to know any details about it (.75) | |||

| It shows that I am inferior (.48) | |||

| Factor 12—active resistance | −.32 | 3.82 | .001 |

| I want to escape from it (.61) | |||

| I feel depressed about it (.52) | |||

| It is like an enemy (.46) | |||

| I must fight it (.38) | |||

| Factor 13—self-pity | −.22 | 2.55 | .012 |

| I cannot think of any reason to do with me why I should have it (.68) | |||

| It is wrong that I have to suffer it (.64) | |||

| It is a punishment that I do not deserve (.60) |

Semi-partial correlation controls for gender.

Numbers in parentheses are factor loadings.

Adherence with medical treatment

Four-day adherence

An index of the degree to which participants took their medications as prescribed was obtained by dividing the total doses taken by total doses prescribed over the past 4 days (Chesney et al., 2000). Four-day recall adherence was negatively skewed, with 81 percent of participants reporting perfect 4-day adherence and 86 percent reporting greater than 90 percent adherence. A regression analysis showed that self-compassion was marginally associated with greater adherence, sr = .14, t(160) = 1.72, p = .08, but the skewed nature of the data raises questions about the validity of this analysis.

Participants were then split into two groups depending on whether their 4-day adherence was less or greater than 90 percent—the minimum level of adherence generally viewed as essential for patients on ART. A t-test was conducted to examine self-compassion scores for participants who were more versus less adherent than 90 percent. Although the pattern was in the expected direction, with more adherent participants having higher self-compassion scores (M = 27.1) than less adherent participants (M = 24.2), the effect was not significant, t(146) = 1.59, p = .12.

Missing medications

Self-compassion predicted the last time that participants missed taking any of their medications, but the effect was not significant at the .01 level, sr = .16, t(173) = 2.19, p = .03. Participants indicated how often they missed taking their medications for each of several reasons. A main effect of self-compassion was obtained on only one reason—feeling depressed or overwhelmed, sr= −.28, t(155) = 3.69, p < .001.

In addition, a two-way interaction of self-compassion and gender was obtained on missing medications because one was away from home, sr = −.20, t(154) = 2.59, p = .01. For men, self-compassion was unrelated to this reason for missing medications, p > .37. For women, self-compassion was inversely related to missing medications because one was away from home, sr = −.37, t(55) = 2.99, p = .004.

Discussion

As predicted, self-compassion was consistently related to how people living with HIV reported dealing with their disease with respect to their emotional reactions, health-related behavior, and social relationships. Overall, self-compassion was related to more beneficial responses involving both better psychological adjustment and more adaptive behaviors.

As expected, self-compassion was associated with less negative emotion, including lower stress, self-pity, and shame. As noted, research has shown that people who score higher in self-compassion not only report higher positive affect and lower negative affect in general, but they also react less negatively to specific unpleasant and stressful events (Allen et al., 2012; Leary et al., 2007b; Magnus, 2007; Neff et al., 2005, 2007b; Sbarra et al., 2012). Not surprisingly, then, our participants reported less negative affect the higher they scored in self-compassion. In fact, participants who were higher in self-compassion were even able to find benefit in being HIV infected (as shown on results for the Positive Stressor factor of the Response to Illness Questionnaire) and showed evidence of coping more successfully with their illness. These finding are, by themselves, of considerable importance given the heavy emotional impact that chronic diseases, such as HIV, have on those who suffer from them. All three facets of self-compassion identified by Neff (2003b) presumably contribute to adaptive emotional responses to chronic disease: common humanity reminds people that their experiences are shared by others, mindfulness is associated with keeping events in perspective, and self-kindness leads people to treat themselves compassionately and not to inflict further suffering upon themselves through self-judgment.

Self-compassion was also related to engaging in adaptive behaviors, including disclosing one’s HIV status to other people (including sexual partners, people with whom one shares needles, and family members), obtaining information, seeking medical care, and adhering to treatments. Not only did self-compassion correlate with such behaviors, but participants who were lower in self-compassion explicitly indicated that shame about being HIV infected interfered with their willingness to seek medical and psychological care, get information about HIV, and adhere to medical treatments. Furthermore, self-compassionate participants reported missing their medications less often. Although the behavioral data for 4-day adherence were problematic because most participants were adherent, self-compassion was marginally associated with greater adherence. Overall, most effects were obtained for both male and female respondents.

Although this study focused on HIV, people who are high in self-compassion presumably deal with a broad array of illnesses, injuries, impairments, and other medical conditions more successfully than people who are low in self-compassion. People who are high in self-compassion react more quickly to signs that they are ill or injured (Terry et al., 2012) and are more likely to accept help when it is needed (Allen et al., 2012). The present results conceptually replicate these previous findings in showing that self-compassionate people engage in greater self-care, seek interaction with others, and view their situation with greater optimism, reactions that promote coping and counteract rumination that can lead to anxiety and depression. Future research should explore more fully differences in how people who are high versus low in self-compassion think about and respond to medical problems.

The results of this study have important implications for helping patients to cope with illnesses and injuries of all kinds, particularly those that involve chronic and potentially fatal conditions. The findings suggest that psychoeducational interventions that teach people to approach their illness with self-compassion should enhance the affective and behavioral reactions demonstrated in this study. Although most research has focused on individual differences in self-compassion (Neff, 2009), people can be taught to respond more self-compassionately. Even brief experimental interventions that lead people to reframe problems in a self-compassionate manner lower negative emotions and reduce maladaptive behaviors that are fueled by negative affect (Adams and Leary, 2007; Gilbert and Irons, 2005; Gilbert and Procter, 2006; Leary et al., 2007). Furthermore, interventions that promote self-compassion reduce self-criticism and shame, and ameliorate the dysfunctional reactions that often accompany self-blame (Gilbert and Irons, 2005; Gilbert and Procter, 2006). Thus, increasing self-compassion could lower illness-related shame and the maladaptive coping and behavioral responses that are often seen in the case of HIV and other illnesses. In addition, increased self-compassion should encourage successful coping, optimism, engagement with others, and medical adherence, all of which are associated with a healthy response to illness. Further research is needed to examine the impact of brief self-compassion interventions on emotional responses, behaviors, and illness-related coping across a spectrum of illnesses and other medical conditions.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by the Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (5P30 AI064518).

Footnotes

After the present study was conducted, Raes et al. (2011) published another 12-item version of Neff’s (2003a) Self-compassion Scale that included a slightly different set of items.

References

- Adams CE, Leary MR. Promoting self-compassionate attitudes toward eating among restrictive and guilty eaters. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26:1120–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Allen AB, Goldwasser ER, Leary MR. Self-compassion and well-being among older adults. Self and Identity. 2012;11:428–453. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2011.595082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brion JM, Menke EM. Perspectives regarding adherence to prescribed treatment in highly adherent HIV positive gay men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho FT, Morais NA, Koller SH, et al. Protective factors and resiliencein people living with HIV/AIDS. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2007;23:2023–2033. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007000900011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Pozo C, Harris SD, et al. How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: A study of women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:375–390. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers D, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:725–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement U, Schönnesson LN. Subjective HIV attribution theories, coping and psychological functioning among homosexual men with HIV. AIDS Care. 1998;10:355–363. doi: 10.1080/713612416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology; Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman CL. Spirituality and sexual orientation: Relationship to mental well-being and functional health status. Advances in Nursing. 2003;43:457–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess DG, Minor S, Antoni MH, Millon T. Utility of the Millon Behavioral Medicine Diagnostic (MBMD) to predict adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) medication regiments among HIV-positive men and women. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;89:277–290. doi: 10.1080/00223890701629805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P, Irons C. Therapies for shame and self-attacking, using cognitive, behavioural, emotional imagery and compassionate mind training. In: Gilbert P, editor. Compassion: Conceptualisations, Research and Use in Psychotherapy. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 263–325. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P, Procter S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2006;13:353–379. [Google Scholar]

- Grierson J, Koelmeyer RL, Smith A, et al. Adherence to antiviral therapy: Factors independently associated with reported difficulty taking antiretroviral therapy in a national sample of HIV-positive Australians. HIV Medicine. 2011;12:562–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CA. Gender differences in HIV-related psychological distress in heterosexual couples. AIDS Care. 1995;7:33–38. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Tate EB, Adams CE, et al. Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:887–904. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus CM. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of Saskatchewan; Canada: 2007. Does self-compassion matter beyond self-esteem for women’s self-determined motives to exercise and exercise outcomes? [Google Scholar]

- Maher K, DeVries K. An exploration of the lived experiences of individuals with relapsed multiple myeloma. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2011;20:267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannheimer SB, Mukherjee R, Hirschhorn LR, et al. The CASE adherence index: A novel method for measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2006;18:853–861. doi: 10.1080/09540120500465160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L, Kagee A. Lifetime and HIV related PTSD among persons recently diagnosed with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15:125–131. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9498-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D, Pedersen C, Eron JJ, Jr, Schwartz T. Emotional distress in African women with HIV. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2007;33:35–50. doi: 10.1300/J005v33n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. Development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003a;2:223–250. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity. 2003b;2:85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. Self-compassion. In: Leary MR, Hoyle RH, editors. Individual Differences in Social Behavior. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 561–573. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Vonk R. Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. Journal of Personality. 2009;77:23–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Hseih Y, Dejitthirat K. Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self and Identity. 2005;4:263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Kirkpatrick K, Rude SS. Self-compassion and its link to adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007a;41:139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Rude SS, Kirkpatrick K. An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007b;41:908–916. [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld S, Sikkema KJ, Lee RS, et al. The development and psychometric properties of the HIV and abuse related shame inventory (HARSI) AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:1063–1074. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0086-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CR, Simoni JM, Hoff P, et al. Assessing antiretroviral adherence via electronic drug monitoring and self-report: An examination of key methodological issues. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:161–173. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9133-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persons E, Kershaw T, Sikkema KJ, et al. The impact of shame on health-related quality of life among HIV-positive adults with a history of childhood sexual abuse. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24:571–580. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro CAT, De-Carvalho-leite C, Drachler ML, et al. Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV/AIDS patients: A cross sectional study in southern Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2002;35:1173–1181. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2002001000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard M. Reaction to illness in long term haemodialysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1974;18:55–67. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(74)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard M. Further studies of illness behaviour in long term haemodialysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1977;21:41–48. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(77)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, et al. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2011;18:250–255. doi: 10.1002/cpp.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis RS, Hino AA, Anez CR. Perceived Stress Scale: Reliability and validity study in Brazil. Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15:107–114. doi: 10.1177/1359105309346343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, et al. Differential HIV risk behavior among men who have sex with men seeking health-related mobile van services at diverse gay-specific venues. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:822–831. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Gershuny BS, Hendriksen E. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress and death anxiety in persons with HIV and medication adherence difficulties. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17:657–664. doi: 10.1089/108729103771928717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra D, Smith HL, Mehl MR. When leaving your ex, love yourself: Observational ratings of self-compassion predict the course of emotional recovery following marital separation. Psychological Science. 2012;23:261–269. doi: 10.1177/0956797611429466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlebusch L, Govender RD. Age, gender, and suicidal ideation following voluntary HIV counseling and testing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2012;9:521–530. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9020521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry ML, Leary MR. Self-compassion, self-regulation, and health. Self and Identity. 2011;10:352–362. [Google Scholar]

- Terry ML, Leary MR, Mehta S. Self-Compassion and Health-Related Behavior. Durham, NC: Duke University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Valldeoriola F, Coronell C, Pont C, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical factors influencing the adherence to treatment in Parkinson’s disease: The ADHESON study. European Journal of Neurology. 2010;18:980–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Achterberg T, Holleman G, Cobussen-Boekhorst H, et al. Adherence to clean intermittent self-catheterization procedures: Determinants explored. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17:394–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]