Abstract

Recognizing the gap between high quality care and the care actually provided, health care providers across the country are under increasing institutional and payer pressures to move towards more high quality care. This pressure is often leveraged through data feedback on provider performance; however, feedback has been shown to have only a variable effect on provider behavior. This study examines the cognitive behavioral factors that influence providers to participate in feedback interventions, and how feedback interventions should be implemented to encourage more provider engagement and participation.

Keywords: audit and feedback, chronic disease management, quality improvement, implementation science

INTRODUCTION

Provider feedback, or providing a summary to health care providers of how their care meets clinical performance measures, is a commonly used method for improving the management of chronic diseases (Casalino, 2003). It is the basis for pay-for-performance and other new payment models to place more pressure on individual providers to improve health care quality. Yet, the impact of provider feedback on outcomes has been inconsistent (Jamtvedt, Young, Kristoffersen, O’Brien & Oxman, 2006), and little is known about why some feedback interventions succeed and others fail.

Meta-analyses have found that successful feedback interventions tend to be written down, given frequently, and associated with other behavioral interventions such as performance targets and action plans (Gardner, Whittington, McAteer, Eccles & Michie, 2010; Hysong, 2009). However, little research has elucidated what factors influence individual providers to engage with a feedback intervention. Some studies observed that physicians’ baseline performance had little effect on their ability to respond to the intervention (Gardner, et al., 2010). Physicians were also noted to value accurate data supported by leaders at their institution (Bradley, et al., 2004).

Our clinic had a newly-implemented electronic medical record (EMR) system, and was engaging in a multifaceted intervention to provide more clinic-based and community-level resources to help patients with diabetes (Peek, et al., 2012). We and our clinic providers were interested in using the data tracked by the EMR to improve the quality of our diabetes care, but there was no straightforward way for clinicians to access the data from the initial implementation of our EMR system. Thus, we worked with our information technology department to develop a feedback intervention that used EMR data to create a roster or list of each provider’s diabetic patients, and give each provider this roster to order follow-up actions (e.g. appointments, endocrinology referrals) for their patients. The aim of our intervention was to encourage the intensification of care for patients with poorly-controlled diabetes, and to determine how this population-level feedback data would be used.

In this mixed-methods analysis, we built on the social cognitive constructs of “outcome expectancy,” or the anticipated benefit of an intervention, and “perceived control,” or the perception of the available resources to realize that benefit (Bandura, 2004), to discover what factors affected provider participation in our feedback intervention.

METHODS

Roster-Based Feedback Intervention

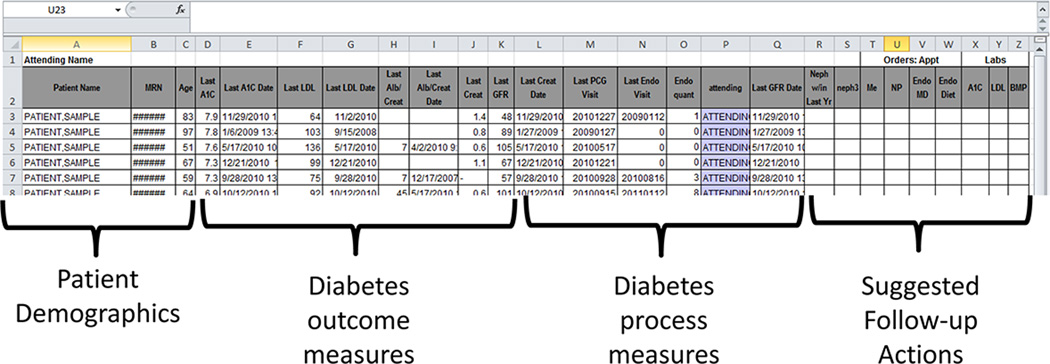

The intervention was piloted with the 37 faculty providers practicing at a general internal medicine clinic at an academic medical center. The aim of the intervention was to improve population-level management of patients with diabetes, particularly among patients with poor diabetes control who may need further services (e.g. endocrinology referral, nurse practitioner case management, etc.). The intervention consisted of a roster of the physicians’ diabetes patients (Figure 1), their latest process measures (e.g. last clinic appointment), and outcome measures (e.g. last hemoglobin A1c value). The roster also allowed providers to order follow-up actions, e.g. checking a box on the roster to schedule an endocrinologist referral. Providers were directed to review the roster and submit the completed spreadsheet to a clinic coordinator on the quality improvement team who would execute the ordered follow-up actions.

Figure 1. Example Feedback Roster.

The rosters were created from data collected from the EMR (Epic Ambulatory). The content and format of the rosters were determined by two physicians and a nurse practitioner in the group involved in diabetes quality improvement activities. The hospital IT department was contacted to manually create these rosters for the pilot project. The rosters were distributed by the clinic’s medical director by email and at a faculty meeting where the intervention and follow-up options were explained and clinic-wide averages were provided. No lab value (e.g. hemoglobin A1c) goals were set for the intervention, but providers were encouraged to use the rosters and follow-up actions provided to improve their diabetes care based on their personal practice preferences.

Survey

We surveyed faculty providers three months after they received the feedback rosters. Surveys were administered electronically or by paper. The survey questions used a five-point Likert scale (i.e. 1 - strongly disagree, 2 - disagree, 3 - neither agree nor disagree, 4 - agree, 5 - strongly agree) to assess provider beliefs about the roster, their patient load, and what is needed to improve diabetes care at the clinic. The survey also assessed whether providers reviewed and responded to the rosters. Providers were also given space to provide open-ended responses regarding strategies to enhance the clinic’s diabetes care.

Interviews

Seven randomly selected providers were interviewed about the value they placed on the feedback intervention. Interviewees were also asked about their perceptions regarding clinic needs to improve diabetes care. The interview guide utilized open-ended questions with probes for clarification and exploration of topic areas. The interviews were on average half an hour in length. Each interview was audio-taped and transcribed for analysis. Using modified template analysis (Crabtree & Miller, 1992), a codebook was developed and iteratively amended by three reviewers (CL, AW, MQ). These three reviewers also analyzed all of the transcripts independently and then came to a consensus on coding through group discussion.

RESULTS

Survey Results

Thirty-five (95%) of the providers responded to the survey. They were 57% female, 62% non-Hispanic White and half (49%) were associate professors or professors. Twenty-seven (77%) of the physicians indicated that they had reviewed the roster. Of the providers that reviewed the roster, 15 (60%) agreed or strongly agreed that the rosters were useful and 12 (44%) agreed or strongly agreed that the follow-up actions were helpful. However, only 11 (31%) of the physicians surveyed noted that they both reviewed the roster and responded to it by ordering the follow-up actions provided.

The most commonly-cited reason (71%) for not responding to the rosters was not having enough time to do so (Table 1). Other themes highlighted included misplacing the rosters, not understanding how to respond to the rosters and not receiving the rosters. A notable number of physicians (21%) also wrote in responses that expressed that the rosters put too much burden on individual physicians to “confront insoluble problems” and that the rosters were not usable in the healthcare system where they were working.

Table 1.

Reasons That Providers Did Not Respond to the Rosters (n=24)

| Reason | No. of Providers (%) |

|---|---|

| Not enough time | 17 (71%) |

| Misplaced or forgot | 7 (29%) |

| Did not understand how to respond | 5 (21%) |

| Did not receive | 5 (21%) |

| Did not find report applicable to my practice | 1 (4%) |

| Other* | 5 (21%) |

Some themes highlighted in the write-in responses under “other” include “system not amenable to working with it,” and “I understand this but have limited time to act on insoluble problems.”

Note: providers were asked to “check all that apply” of these options listed. Thus the N and % of providers in this table do not sum up to 24, or 100%.

Interview Results: Expected Outcome in Intervention Participation

Most providers interviewed noted that the rosters provided useful information either because it provided new insights or made them aware of patients that “have kind of fallen through the cracks.” As one provider noted:

In terms of patients that are poorly controlled, I think I am aware of that anyway. I think [the roster’s] main value may be patients who have not come in recently that I am not aware of that maybe they could be given reminders…

Another provider noted:

You get common themes out of this. Am I someone who is not checking protein or microalbumin enough? I think it is really good feedback. If you are not monitoring yourself, then you can't begin to think about how to improve your care.

However, when questioned further about the expected outcome of this intervention, most providers also noted that the roster would not change their clinical behavior. As one provider said,

I get it, we want to improve quality, but here is a sheet of paper, we are not going to do anything about it.

Others noted that when given their actual roster, its effect on changing their behavior was limited because the outliers on the roster were patients they were already monitoring or because there was too much time between seeing the roster and talking to the patient:

With this roster in front of me, without the patient in front of me, there is nothing actual about this. I am not going to go through this list and start calling these people.

Providers also noted that they were not able to easily apply the information on the roster to their practice:

[I am not] totally clear [on] how I should best use these values. The A1C or the LDL is a little more self-evident, right? Like if the A1C is 12, we got a problem here. Looking at their last endo visit may or may not give me information that is really important or easy to interpret.

Interview Results: Perceived Control in Intervention Participation

When questioned regarding what they felt would be useful changes for improving diabetes care at the primary care group, providers highlighted many areas where they felt they lacked sufficient control over their practice. As one provider stated, they did not feel their efforts were sufficient to make a difference in the patient’s life:

It is not that I can't do anything, but the amount of effort put into the potential benefit statistically – the [cost benefit] ratio, the output/input – I would be moving her very incrementally and in terms of her overall quality of life or quantity of life or morbidity, probably incrementally, very small what I could possibly do for her based on this sheet of paper.

Another theme highlighted included not enough time to handle patient needs outside of the constraints of a twenty minute visit. As one provider noted:

I am busy and I often don't see patients for a long time and maybe they just need a call or maybe to come in for some labs and a dose adjustment of the medicines they are already taking. I could be better at that, but what happens is they discharge them by giving them an appointment and I don't think about them until they come back because it is easier.

Providers also expressed a need for more patient education resources. As one provider noted,

I think that there are a lot of people who I feel do need more nutrition education, which we have not really had great ability to provide to them. I know there is a diabetes educator in endocrinology for nutrition, but it is not so easy to get patients in from my experience.

Another theme included the lack of ownership of patients co-managed by an endocrinologist. As one provider noted:

Many of these patients may be managed in endocrinology or other specialties…so I may defer their diabetes management to [the endocrinologist] and then focus on the other problems they have. Even if they’re poorly controlled going to endocrine, then I may or may not get involved with their diabetes.

In addition, many providers described having limited capacity to improve the quality of patient care without clinic-wide action. In particular, many providers expressed that too much burden was being placed on the primary care physician alone, for example:

I think that in clinic in 20 minutes trying to do all you’re doing in that visit, it's nearly impossible. Especially like reviewing all the medications. For example, in some clinics, they have some, you know, they have an assistant or someone who reviews the medications with the patients … and then just comes to the physician with any questions or things that are discrepant because it is just not possible in that visit to do that every single visit. Things like that. Things that don't have to be done by the doctor, but are really critical and they get more of a team approach.

As another provider noted:

I think that these [provider feedback] tools in the absence of those resources and those algorithms are simply yet another mandate [for primary care physicians] on top of an already busy schedule that for many us is already full.

DISCUSSION

No provider feedback intervention can be successful unless it engages the providers targeted by the intervention. Though previous studies have focused on factors of the intervention itself, our study highlights how provider perceptions of themselves and their clinic affect their participation in a feedback intervention.

Consistent with previous researchers’ findings (Bradley, et al., 2004; Gardner, et al., 2010), we found that most providers hesitated to participate in the intervention because they did not find it “actionable.” Specifically, they were concerned that the rosters did not deliver information at a time when the information could be acted upon immediately. They also felt that the current intervention’s format demanded increased cognitive effort to go through the feedback provided, review the relevant charts and determine the appropriate actions that needed to be ordered.

Providers were also concerned about how rosters forced them to confront what they saw as “insoluble problems.” They expressed the perception that an individual provider’s efforts towards population-level quality improvement would have only a small effect on diabetes patient outcomes. In social cognitive terms, the providers had poor perceptions of the expected outcome of the intervention due to their lack of perceived control over diabetes care.

Though systems factors were not measured directly, our providers highlighted a number of aspects of the medical practice that limited their perceived ability to improve diabetes care. These aspects included numerous demands on their time and the insufficient resources in the clinic, especially limitations regarding access to ancillary care personnel such as nutritionists or diabetes educators. They also described the need for more “team-based care,” that is, more clinic-wide actions to standardize and improve diabetes care and better communication and more shared responsibility with referral resources, such as the endocrinology department and nutritionists.

Our study suggests that other quality improvement teams should make three things clear before implementing a provider feedback intervention. First, they should clearly articulate the purpose of providing the feedback information. Is it to catch patients that have fallen through the cracks? Is it to streamline referrals to a more intensified care management system? Regardless of what benefit is focused upon, this specific aim needs to be determined and made clear to providers. As much as possible, providers should be engaged in the process of designing and setting the aims of the feedback intervention. Though this was done with a few providers at the early stages of our intervention, our intervention would have benefited from continuous provider engagement, iterative redesign and re-focusing of our intervention based on provider input. In social cognitive terms, by defining specific aims of our intervention, we would have improved providers’ perception that the expected outcome was attainable, and decreased their sense that the outcome was outside of their control.

Second, initial investments of time and resources should be made to allow providers to respond to the intervention and to ensure that the system is responsive to the provider recommendations (e.g. care coordination staff, mechanisms to link patients to community resources). A key finding of our study is that roster review requires significant resources beyond the creation of the roster itself. For providers, reviewing rosters is a time-consuming process, especially when they are not used to population management and minimal guidance is provided to help automate the process. Thus, additional clinical time should be dedicated for physicians to review the rosters. This clinical time may include setting up systems or dedicating personnel to streamline roster review. Another way of reducing the time requirement for roster review would be if providers are given the feedback within their regular workflow, e.g. within the context of the patients they are seeing in clinic that day. With the patient in front of them, providers would require less intellectual effort and time to take action on the information provided through the rosters.

Third, quality improvement teams should reinforce provider knowledge of and trust in the resources available in their clinic and health system. For example, our roster included follow-up actions through which providers could intensify care by referring to other providers, e.g. a nurse practitioner or the endocrinology clinic. Though many providers recognized the benefit of these resources, they felt uncomfortable acting when they still had many doubts about the availability of such services (e.g. how long the waitlist was to see a nutritionist) and without a clear channel of communication between themselves and their referral providers. This communication about available resources and support is critical to create a sense of believable impact around the roster review process.

Our study is limited by a single clinical setting, but many of our providers’ concerns are likely prevalent in other high-volume primary care practices.

Provider feedback may seem a relatively inexpensive and simple initial step towards improving the quality of care for patients with chronic disease, but without effective systems in place to support the intervention, feedback alone is insufficient. Providers need time to respond to the feedback and access to resources such as patient education and care coordination to take the actions needed to improve patient care. Providers also need to perceive that their clinic’s resources to improve patient care are readily available and effective. In this study, we found that what was critical to this perception was not just a lack of resources, but also a lack of communication and clarity. Feedback interventions need to be clear about 1) what they are trying to achieve, setting concrete goals that providers believe in, and 2) how they are trying to achieve it, with what resources and through which communication channels. Without this clarity, providers in our intervention believed that the time they invested in reviewing the rosters would not bring the available resources to bear in a meaningful way to improve diabetes care. This experience highlights how quality improvement projects, particularly those focused on feedback, can only succeed if the targets of the intervention (in this case, primary care providers) believe that the intervention will ultimately impact health systems and patients.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This research study was supported by the Merck Foundation Alliance to Reduce Disparities in Diabetes, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) R18 DK083946, and the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (NIDDK P30 DK092949). Dr. Lu was also supported through the Scholarship and Discovery Program of the Pritzker School of Medicine (NIDDK T35 DK062719). Dr. Chin was also supported by a NIDDK Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 DK071933).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflict of Interests

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest with this work.

Contributor Information

C. Emily Lu, Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Lisa M. Vinci, Section of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Michael T. Quinn, Section of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Abigail E. Wilkes, Section of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Marshal H. Chin, Associate Chief and Director of Research, Section of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Monica E. Peek, Section of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

REFERENCE LIST

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E, Holmboe E, Mattera J, Roumanis S, Radford M, Krumholz H. Data feedback efforts in quality improvement: lessons learned from US hospitals. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2004;13(1):26–31. doi: 10.1136/qhc.13.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalino L. External incentives, information technology, and organized processes to improve health care quality for patients with chronic diseases. JAMA. 2003;289(4):434–441. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WF. A template approach to text analysis: developing and using codebooks. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1992. pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B, Whittington C, McAteer J, Eccles MP, Michie S. Using theory to synthesise evidence from behaviour change interventions: the example of audit and feedback. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(10):1618–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hysong SJ. Meta-analysis: audit and feedback features impact effectiveness on care quality. Medical Care. 2009;47(3):356–363. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181893f6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, O’Brien MA, Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;2006(2):1–83. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Wilkes AE, Roberson TS, Goddu AP, Nocon RS, Tang H, Chin MH. Early lessons from an initiative on Chicago’s south side to reduce disparities in diabetes care and outcomes. Health Affairs. 2012;31(1):177–186. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]