Abstract

Background

Reexpansion pulmonary edema (RPE) is a rare complication that may occur after treatment of lung collapse caused by pneumothorax, atelectasis or pleural effusion and can be fatal in 20% of cases. The pathogenesis of RPE is probably related to histological changes of the lung parenchyma and reperfusion-damage by free radicals leading to an increased vascular permeability. RPE is often self-limiting and treatment is supportive.

Case report

A 76-year-old patient was treated by intercostal drainage for a traumatic pneumothorax. Shortly afterwards he developed reexpansion pulmonary edema and was transferred to the intensive care unit for ventilatory support. Gradually, the edema and dyspnea diminished and the patient could be discharged in good clinical condition.

Conclusion

RPE is characterized by rapidly progressive respiratory failure and tachycardia after intercostal chest drainage. Early recognition of signs and symptoms of RPE is important to initiate early management and allow for a favorable outcome.

Keywords: Trauma, Pneumothorax, Pulmonary edema, Chest drainage, Reexpansion

Introduction

We describe the case of a patient suffering from reexpansion pulmonary edema (RPE) after chest drainage for pneumothorax. This condition is a relatively unknown complication of intercostal chest drainage and is potentially lethal in 20% of cases [1]. Therefore, early recognition of signs and symptoms is important since inadequate or delayed treatment may lead to a fatal outcome.

Case report

A 76-year-old male patient suffering from Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease had difficulties walking and was admitted to the neurology ward because of frequent falls. Two days after admission, the patient was delirious and fell out of bed again. The neurological resident who examined the patient found absent breathing sounds on the left hemi thorax. A chest X-ray showed a complete left-sided pneumothorax and a single, non-dislocated fracture of the seventh rib (Fig. 1). An intercostal drainage tube (ICD) was inserted and 350 mL of serosanguineous fluid was instantly drained whilst suction of 15 cm H2O was applied. A second chest X-ray showed a fully re-expanded left lung (Fig. 2) and oxygen saturation was 100% with 2 L of oxygen. However, 2 h after the insertion of the ICD, the patient became severely dyspneic and his oxygen saturation level dropped to 66%. Neither severe blood loss, air leakages from the ICD or serum abnormalities (Hb, Leucocytes) were observed.

Fig. 1.

Complete left-sided pneumothorax, costa 7 fracture.

Fig. 2.

Fully expanded lung after intercostal drain (ICD) insertion.

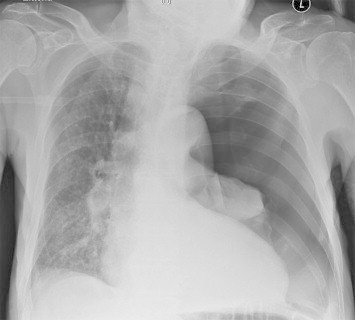

A repeated chest X-ray showed signs of severe pulmonary edema on the left side (Fig. 3). The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and received continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy. The pulmonary edema diminished gradually within a week (Fig. 4) and the patient could be transferred back to the neurology ward for further treatment of his Parkinson's disease. He was discharged to a nursing home three weeks later in good condition.

Fig. 3.

Reexpansion pulmonary edema 2 h after drainage.

Fig. 4.

Diminished pulmonary edema after 7 days, ICD removed.

Discussion

History and epidemiology

In 1853, Pinault was the first to describe the formation of pulmonary edema after thoracocentesis [2]. More than a century later, Carlson described the first case of pulmonary edema after pneumothorax [3].

Mahfood et al. published a review of 47 case reports of RPE in 1959 [1]. In this study population, the male to female ratio was 38:9 and the mean age was 42 years. In 83% of the cases, the pneumothorax was present for at least three days; in seven patients however, it had been present for just a couple of hours. Edema developed within 1 h after ICD placement in 64% of the cases. All other patients developed edema within 24 h. Almost all patients (94%) had ipsilateral edema whereas three patients suffered from bilateral edema.

The incidence of RPE described in the literature varies remarkably. This maybe due to the large variety of symptomatology and unfamiliarity with the diagnosis. In two studies that investigated spontaneous pneumothorax (400 and 375 cases respectively) no cases of RPE were reported [4,5]. Matsuura et al. on the other hand reported RPE in 14% of 146 patients with spontaneous pneumothorax and in 17% of the patients with a total pneumothorax [6].

The mortality rate of patients suffering from RPE is reported to be up to 20% [1].

Clinical presentation and treatment

Patients typically present with rapidly progressive dyspnea and tachypnea, usually within 1 h after intercostal drainage. Other symptoms include productive cough, tachycardia, hypotension, cyanosis, fever, chest pain, nausea and vomiting [1,7]. Symptoms may vary from mild radiographic changes to respiratory failure and signs of adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

A chest X-ray may show a unilateral alveolar filling pattern within 2–4 h after reexpansion, which may progress over 48 h and persist for 4–5 days. The edema resolves in 5–7 days without remaining radiographic abnormalities [7]. The most common findings on a computed tomography (CT)-scan include ipsilateral ground-glass opacities, septal thickening, foci of consolidation, and areas of atelectasis [8]. RPE is usually a self-limiting disease and most often does not need any intervention [13]. Almost all patients who recover do so within a week.

The treatment of RPE is supportive and consists of oxygen or CPAP support. In some cases intubation and mechanical ventilation with positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) will be necessary. Intrapulmonary shunting of lung tissue can create hypoxia and/or hypovolemia. In this case, administration of fluids, plasma expanders and/or inotropics are required whereas diuretics are contra-indicated because they can exacerbate hypovolemia [13]. Lateral decubitus positioning on the affected side can reduce shunting and improve oxygenation. Unilateral ventilation is seldom necessary [18].

Pathophysiology

In the 1980s, RPE was thought to originate from an increased permeability of damaged pulmonary blood vessels, caused by a swift reexpansion of the lung tissue [9]. According to Sohara, blood vessels are vulnerable to this traction because of histological changes that occur during the chronic lung collapse [9], whereas Gumus et al. suggested that after reexpansion, reperfusion of the ischemic lung will increase free oxygen radicals and anoxic stress, leading to damage of the vascular endothelium [10]. As an alternative explanation, Sue et al. postulated that the lung tissue consists of heterogenous areas of hypoxic vasoconstriction and that pulmonary edema will originate because of hydrostatic pressure in these areas where high perfusion pressure is combined with more negative pressure, decreased lymph flow or venous constriction [11]. Although all factors might contribute to formation of RPE, maybe none of them is essential. This might be why predicting the occurrence of RPE is so difficult.

Risk factors

Multiple authors have investigated possible risk factors for RPE. Matsuura et al. reviewed 146 cases of spontaneous pneumothorax and found that RPE incidence was significantly higher in patients aged 20–39 years than in patients aged >40 years. No statistically significant differences in incidence of RPE were noted for gender, side of collapsed lung, pulmonary co-morbidities, history or signs and symptoms of pneumothorax [6]. Not one patient suffering from a pneumothorax sized less than 30% of lung fields developed RPE. In contrast, 17% of the patients with pneumothorax sized >30% of lung fields and 44% of the patients with tension pneumothorax developed RPE [6].

In animal studies performed by Miller et al., RPE did not develop when a pneumothorax was drained within 3 days [12]. In humans however, duration maybe of less importance than the size of the pneumothorax. Probably, patients with a larger pneumothorax may seek medical help more quickly because of more severe symptoms. Still, Matsuura et al. suggest that in patients with a moderate extent of lung collapse, longer duration of symptoms is possibly associated with higher rates of RPE when compared to the duration of symptoms for less than one day [6].

Prevention

No randomized clinical trial has yet been performed to compare the effects of different methods of drainage but many articles suggest that the method of chest drainage and thus the rapidity of reexpansion might play a role in the development of RPE [1,3,6,7,9,13].

In concordance with a consensus statement of an American College of Chest Physicians, most authors advise to drain not more than 1 L of fluid or air at once and to use water valves instead of suction, even though Abunasser and Brown concluded that a large-volume thoracentesis is a safe procedure to perform [14–16].

The maximal volume of air or fluid to be drained at once is estimated to be 1200–1800 mL. It is advised to stop drainage when the patient starts coughing, as it might be a first sign of edema formation [7].

Several studies have been performed to investigate the usefulness of interventions such as oxygen supplementation or the administration of anti-oxidants during reexpansion. The authors concluded that these interventions could prevent RPE, but these studies concern only small study populations [10,16,17].

Conclusion

RPE is a possibly life-threatening but relatively unknown condition. Therefore its occurrence is often not recognized as a complication of chest drainage after pneumothorax. Signs and symptoms include dyspnea, tachypnea and low saturation levels usually within an hour after intercostal drainage.

Risk factors include younger age, more severe or longer existing pneumothorax and maybe a swift drainage of large amounts of fluids or air. Especially in the presence of risk factors, close patient monitoring is indicated during the first hours after drainage.

To prevent RPE it is advised to use water valves instead of vigorous suction and to drain small volumes of air or fluids. The disease is often self-limiting and therapy is supportive.

References

- 1.Mahfood S., Hix W.R., Aaron B.L., Blaes P., Watson D.C. Reexpansion pulmonary edema. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45(3):340–345. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinault: Consideration cliniquesur la thoracentese. 1853. [These de Paris] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlson R.I., Classen K.L., Gollan F., Gobbel W.G., Jr., Sherman D.E., Christensen R.O. Pulmonary edema following the rapid reexpansion of a totally collapsed lung due to a pneumothorax: a clinical and experimental study. Surg Forum. 1958;9:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mills M., Baisch B.F. Spontaneous pneumothorax: a series of 400 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 1965;122:286–297. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)66756-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks J.W. Open thoracotomy in the management of spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Surg. 1973;177(6):798–805. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197306000-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuura Y., Nomimura T., Murakami H., Matushima T., Kakehashi M., Kajihara H. Clinical analysis of reexpansion pulmonary edema. Chest. 1991;100(6):1562–1566. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarver R.D., Broderick L.S., Conces D.J., Jr. Reexpansion pulmonary edema. J Thorac Imaging. 1996;11(3):198–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gleeson T., Thiessen R., Müller N. Reexpansion pulmonary edema: computed tomography findings in 22 patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2011;26(1):36–41. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181ced052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohara Y. Reexpansion pulmonary edema. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;14(4):205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gumus S., Yucel O., Gamsizkan M., Eken A., Deniz O., Tozkoparan E. The role of oxidative stress and effect of alpha-lipoic acid in reexpansion pulmonary edema – an experimental study. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6(6):848–853. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.19290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sue R.D., Matthay M.A., Ware L.B. Hydrostatic mechanisms may contribute to the pathogenesis of human re-expansion pulmonary edema. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(10):1921–1926. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2379-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller W.C., Toon R., Palat H., Lacroix J. Experimental pulmonary edema following re-expansion of pneumothorax. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973;108(3):654–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Herendael H.E., Van den Heuvel M.C., Van Roey G.W., Soetens F.M. Re-expansielongoedeem bij een patient na behandeling van een pneumothorax. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2006;150(5):259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumann M.H., Strange C., Heffner J.E., Light R., Kirby T.J., Klein J. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax – an American college of chest physicians Delphi consensus statement. Chest. 2001;119(2):590–602. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.2.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abunasser J., Brown R. Safety of large-volume thoracentesis. Conn Med. 2010;74(1):23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherman S.C. Reexpansion pulmonary edema: a case report and review of the current literature. J Emerg Med. 2003;24(1):23–27. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(02)00663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yucel O., Ucar E., Tozkoparan E., Gunal A., Akay C., Sahin M.A. Proanthocyanidin to prevent formation of the reexpansion pulmonary edema. J Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;4:40–48. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-4-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dias O.M., Teixeira L.R., Vargas F.S. Reexpansion pulmonary edema after therapeutic thoracentesis. Clinic. 2010;65(12):1387–1389. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010001200026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]