Abstract

Giant cell interstitial pneumonia (GIP) is a rare form of chronic interstitial pneumonia typically associated with hard metal exposure. Only two cases of GIP induced by nitrofurantoin have been reported in the medical literature. We are reporting a case of recurrent nitrofurantoin-induced GIP. Although extremely rare, GIP needs to be included in the differential diagnosis in patients with chronic nitrofurantoin use who present with respiratory illness.

Keywords: Giant cells, Nitrofurantoin, Lung toxicity, Interstitial pneumonia, Metals

Case report

A 76-year old Caucasian priest with hypothyroidism and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) presented to our hospital in 2010 with shortness of breath, a non-productive cough and right-sided pleuritic chest pain of a few weeks duration. He had a 78 pack-year history of tobacco use, but quit in 1986. He had no prior history of asthma, COPD, pneumonia or interstitial lung disease. At baseline, he was very active and had no limitation to exercise. Upon presentation to the hospital, he was experiencing shortness of breath with minimal exertion and reported a 40-pound weight loss and dysphagia. He reported no fevers, chills, wheezing, palpitations, or joint pain. His medications included levothyroxine, calcium, and nitrofurantoin which he had taken daily for approximately 15 years for suppression of UTIs. He had no history of exposure to heavy metals or asbestos. He had a negative PPD test in the 1960's and had no known exposure to tuberculosis.

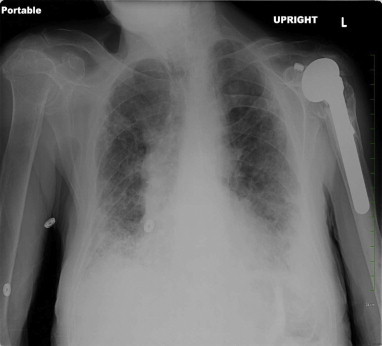

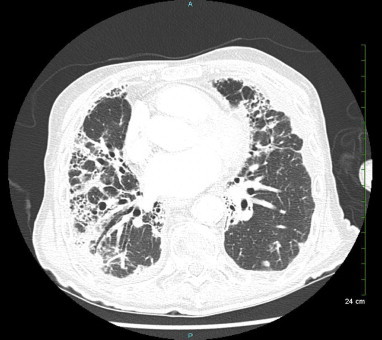

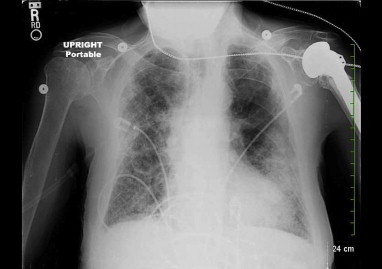

On physical examination, the patient appeared uncomfortable with moderate respiratory distress. Blood pressure was 110/65 mm Hg, heart rate was 85 beats per minute, temperature 97.3 F. He was tachypneic with respiratory rate at 30 breaths per minute and oxygen saturation of 93% at rest on room air. He had diminished breath sounds bilaterally with dry crackles, more prominent on the right side. Laboratory studies revealed a normal white blood cell count of 8.4 × 109/L (reference range: 4.4–5.7 × 109/L) with a normal differential. The chemistry panel was also within normal range. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was over 140 mm/h (normal range: 1–15 mm/h for men). ANA screen was positive, but all other serologies for rheumatologic disorders were negative, including anti-double stranded DNA, Rheumatoid Factor, Scl-70, anti-centromere B, anti-Jo, anti-ribosomal P, anti-RNP, anti-Sm, anti-SS/A and SS/b and ACE level. Testing for HIV 1&2 and Quantiferon TB Gold was negative. CXR showed extensive basilar fibrosis, pleural thickening and possible basilar infiltrates (Fig. 1). Chest computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous contrast showed severe fibrotic changes in both lungs, with honeycombing especially at the lung bases and diffuse pleural wall thickening (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray, (during first hospitalization) shows extensive basilar-predominant fibrosis, pleural thickening and possible pneumonic infiltrates in bilateral lower lobes of the lungs. No previous CXR was available for comparison.

Fig. 2.

CT scan of the chest (during first hospitalization) shows pleural thickening and severe fibrotic changes with honeycombing in both lungs.

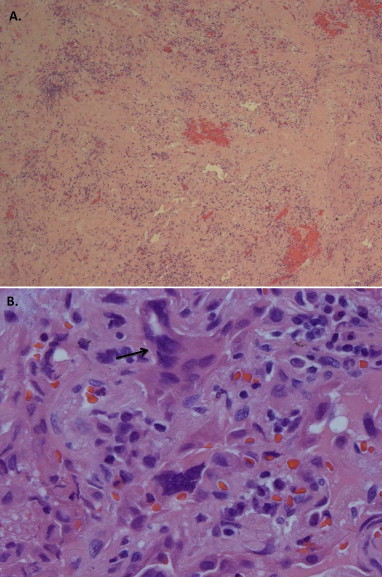

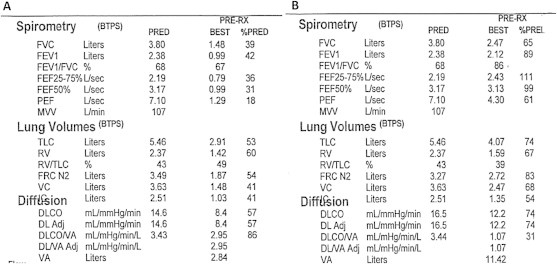

Nitrofurantoin was stopped on the day of hospital admission. The patient underwent video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) with lung and pleural biopsy to establish a diagnosis. The routine aerobic and anaerobic, fungal and mycobacterial cultures from the lung tissue and pleural fluid were all negative. A biopsy specimen from left lower lung demonstrated marked interstitial chronic inflammation, subpleural interstitial fibrosis and numerous prominent multi-nucleated giant cells, consistent with Giant Cell Interstitial Pneumonia (Fig. 3A and B). Since he had no exposure to hard metals, GIP was determined to be due to chronic nitrofurantoin use. He was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily and weaned off steroids over the course of 6 months. His dyspnea on exertion gradually resolved and he was weaned off oxygen as an outpatient. During a visit to pulmonary clinic five months after his initial hospitalization he was noted to have no shortness of breath at rest or with exertion. He was walking 4–5 miles per day and SpO2 was 99% on room air. On a 6-min walk testing, the lowest oxygen saturation on room air was 93%. His physical exam was normal other than mild crackles noted at the right lung base. CXR at that time showed a significant decrease in the pulmonary infiltrates and pleural thickening (Fig. 4). Pulmonary Function Testing (PFT) performed soon after hospital discharge showed a severe obstructive and moderate restrictive ventilatory defect which improved significantly on follow-up PFT performed five months later (Fig. 6A and B).

Fig. 3.

Histology from VATS lung biopsy reveals A) marked fibrosis and chronic inflammation with B) giant cell reactions (hematoxylin-eosin, A.25× B.100×). An arrow shows a multi-nucleated giant cell.

Fig. 4.

Chest X-ray, (4 months after initial hospitalization) shows minimal left sided pleural effusion and a significant decrease in the pulmonary infiltrates and pleural thickening.

Fig. 6.

A: PFT performed approximately 2 months after the initial hospitalization shows a severe obstructive and a moderate restrictive ventilation defect and moderately decreased DLCO. B: PFT performed approximately 4 months later shows a significant improvement with a mild restrictive ventilatory defect, resolution of the obstructive ventilatory defect and only a mildly reduced DLCO.

Two and a half years later, after having no further respiratory complaints, he presented to pulmonary clinic with recurrent fatigue and progressive dyspnea on exertion, which had developed over a 6-week period. He was found to be tachypneic and hypoxemic with SpO2 85% upon walking into the office. Physical exam revealed extensive crackles in both lung bases. A hall walk showed desaturation to 84% at 85 feet of walking. CXR performed that day showed extensive bilateral interstitial infiltrates and opacities (Fig. 5). On further inquiry, he reported that approximately 6 weeks prior to the onset of his recurrent dyspnea. a urologist had placed him back on nitrofurantoin for UTI prophylaxis. Due to the concern of recurrent GIP caused by nitrofurantion, he was instructed to stop nitrofurantoin immediately. He was initially treated as an outpatient with Prednisone 60 mg daily and oxygen. However, on follow-up visit one week later, he was found to be severely dyspneic and tachypneic. SpO2 while on oxygen 4 L/minute decreased from 97% at rest to 81% in less than one minute of walking. He had not been fully complaint with the outpatient steroid regimen prescribed one week earlier. He was directly admitted to the hospital where he was treated with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone 60 mg intravenously every 6 h initially and oxygen. No additional Chest CT or lung biopsy was performed as the patient improved with steroid treatment. He was discharged to a nursing home on oxygen 2 L/min continuously and 6 L/min overnight. He completed another 6-month taper of Prednisone, starting at 60 mg, as an outpatient. Although he has been weaned off steroids and does not have shortness of breath at rest currently, he experiences dyspnea on exertion and requires 3 L oxygen with exercise if walking more than three minutes. He now wears a medical allergy band documenting his allergy to nitrofurantoin.

Fig. 5.

Chest X-ray (during second hospitalization) shows a dramatic increase in bilateral opacities compared with previous CXR.

Discussion

Nitrofurantoin is a synthetic nitrofurane which is active against many gram-negative bacilli including Eschericia coli [1]. It has been widely used to treat urinary tract infections for more than 50 years. It recently became a first-line treatment option for acute uncomplicated cystitis based on its efficacy, low cost and minimal resistance [2]. Nitrofurantoin is also commonly used for chronic suppression of recurrent urinary tract infections [3].

Pulmonary adverse reactions to nitrofurantoin have been well described in the literature. Both acute and chronic manifestations have been reported [4,5]. Acute pulmonary reactions, which occur hours to days into a course of nitrofurantoin, are more common and typically manifest as an eosinophilic pneumonia or hypersensitivity reaction [6,7]. Chronic pulmonary reactions to nitrofurantoin, which occur months to years after daily nitrofurantoin use, present as interstitial pneumonitis and fibrosis. Chronic reactions have been associated with advanced age and prolonged use of nitrofurantoin but a dose-dependent relationship has not been established [6].

Giant cell interstitial pneumonia (GIP) is a rare form of chronic interstitial pneumonia typically associated with hard metal exposure. GIP was first designated as a distinct entity by Liebow and Carrington in 1969 in the histologic classification system of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias [8]. However, GIP was subsequently excluded from the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society 2002 consensus statements on idiopathic interstitial pneumonias [9]. Currently GIP is classified as a pneumoconiosis associated with exposure to hard metals, typically cobalt and tungsten carbide [10]. GIP has also been described in literature as Hard Metal Disease, Giant Cell Pneumonitis and Cobalt Lung. The pathogenesis of GIP remains unclear but an autoimmune mechanism has been suggested [10].

The hallmarks of GIP on lung biopsy are bizarre appearing multi-nucleated giant cells, which have been described as cannibalistic, and centrilobular fibrosis [11]. Interstitial inflammation and organizing pneumonia can also be seen. Advanced GIP lesions present with fibrosis and honeycombing [12]. On high resolution Chest CT scans, GIP can present with ground-glass opacities, irregular linear opacities, small centrilobular nodules and/or honeycombing [13].

While the vast majority of patients with GIP have had a past exposure to hard metals, there have been case reports of GIP associated with viral, mycobacterial, fungal infections and malignancy in patients without hard metal exposure [14]. Only two cases of nitrofurantoin-associated GIP have been reported in the literature [15,16]. All three cases, including ours, share the following characteristics: 1) insidious onset and gradually worsening dyspnea following long-term nitrofurantoin treatment 2) combined mild obstructive and restrictive patterns on pulmonary function tests 3) bilateral infiltration on imaging and 4) good response to nitrofurantoin withdrawal and systemic administration of steroids. Our case report is unique since this lung biopsy proven case of nitrofurantoin-induced GIP, appears to have recurred approximately 3 years later, just six weeks after the reintroduction of nitrofurantoin.

Conclusion

Our case highlights that GIP can occur in the absence of hard metal exposure, can be associated with chronic nitrofurantoin use and can recur if the patient is re-exposed to nitrofurantoin. Early recognition and prompt discontinuation of nitrofurantoin is the mainstay of treatment, along with a course of oral steroids. GIP should be recognized as a potential adverse reaction to nitrofurantoin, and taken into consideration, especially before committing to long-term treatment with nitrofurantoin.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Dr. Teresita Zdunek in pathology department for providing and interpreting a pathology slide for this report.

References

- 1.Garau J. Other antimicrobials of interest in the era of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: fosfomycin, nitrofurantoin and tigecycline. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;1:198–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta K., Hooton T.M., Naber K.G., Wullt B., Colgan R., Miller L.G., Infectious Diseases Society of America. European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e103–e120. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtenberger P., Hooton T.M. Antimicrobial prophylaxis in women with recurrent urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmberg L., Boman G. Pulmonary reactions to nitrofurantoin. 447 cases reported to the Swedish adverse drug reaction committee. Eur J Respir Dis. 1981;62:80–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jick S., Jick H., Walker A., Hunter J.R. Hospitalizations for pulmonary reactions following nitrofurantoin use. Chest. 1989;96:512–515. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmberg L., Boman G., Böttiger L.E., Eriksson B., Spross R., Wessling A. Adverse reactions to nitrofurantoin. Analysis of 921 reports. Am J Med. 1980;69:733–738. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90443-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madani Y., Mann B. Nitrofurantoin-induced lung disease and prophylaxis of urinary tract infections. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21:337–341. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2012.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liebow A., Carrington C. The interstitial pneumonias. In: Simon M., Potchen E.J., LeMay M., editors. Frontiers of pulmonary radiology. 1st ed. Grune & Stratton; New York, NY: 1969. pp. 102–141. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Thoracic Society American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277–304. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katzenstein A., Myers J. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and the other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: classification and diagnostic criteria. Am J Surg Path. 2000;24:1–3. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka J., Moriyama H., Terada M., Takada T., Suzuki E., Narita I. An observational study of giant cell interstitial pneumonia and lung fibrosis in hard metal lung disease. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004407. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naqvi A., Hunt A., Burnett B., Abraham J. Pathologic spectrum and lung dust Burden in giant cell interstitial pneumonia (Hard metal Disease/Cobalt pneumonitis): review of 100 cases. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2008;63(2):51–70. doi: 10.3200/AEOH.63.2.51-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi J., Lee K., Chung M., Han J., Chung M.J., Park J.S. Giant cell interstitial pneumonia: high-resolution CT and pathologic findings in four adult patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(1):268–272. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohori N.P., Sciurba F.C., Owens G.R., Hodgson M.J., Yousem S.A. Giant-cell interstitial pneumonia and hard-metal pneumoconiosis. a clinicopathologic study of four cases and review of the literature. J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:581–587. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hargett C.W., Sporn T.A., Roggli V.L., Hollingsworth J.W. Giant cell interstitial pneumonia associated with nitrofurantoin. Lung. 2006;184:147–149. doi: 10.1007/s00408-005-2574-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magee F., Wright J.L., Chan N. Two unusual pathological reactions to nitrofurantoin: case reports. Histopathology. 1986;10:701–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1986.tb02523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]