Abstract

Background

Young adults with cancer are at increased risk for suicidal ideation. The impact of the patient-oncologist alliance on suicidal ideation has not been examined. This study examined the relationship between the patient-oncologist therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation in young adults with advanced cancer.

Methods

Young adult patients (age 20-40 years; n=93) with incurable, recurrent, or metastatic cancer were evaluated by trained interviewers. Suicidal ideation was assessed with the Yale Evaluation of Suicidality, dichotomized into a positive and negative score. Predictors included diagnoses of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), physical quality of life, social support, and utilization of mental health and supportive care services. The Human Connection Scale, dichotomized into strong (upper third) and weak (lower two-thirds) therapeutic alliance assessed strength of the patients’ perceived oncologist alliance.

Results

22.6% screened positive for suicidal ideation. Patients with a strong therapeutic alliance were at reduced risk for suicidal ideation after controlling for confounding influences of cancer diagnosis, performance status, number of physical symptoms, physical quality of life, MDD, PTSD, and social support. A strong therapeutic alliance was also associated with reduced risk for suicidal ideation after controlling for mental health discussions with healthcare providers and use of mental health interventions.

Conclusions

The patient-oncologist alliance was a robust predictor of suicidal ideation and provided better protection against suicidal ideation than mental health interventions, including psychotropic medications. Oncologists may significantly influence patients’ mental health and may benefit from training and guidance in building strong alliances with their young adult patients.

The suicide rate in cancer patients is twice the rate in the general population.1 Cancer patients are also at greater risk for suicidal ideation than the general population.2 Young adults with cancer may be especially vulnerable to suicidal ideation and behaviors.3 In patients age 17-39 years, cancer was associated with a four-fold increase in the likelihood of a suicide attempt after controlling for depression, alcohol use, and demographic characteristics.4

Developmental characteristics of young adulthood may increase young adults’ vulnerability to suicidal ideation in the context of cancer. Cancer can disrupt normal developmental processes that occur in young adulthood such as the pursuit life goals. Young adults do not typically experience poor health; a diagnosis of cancer may challenge their expectations regarding fairness and how life “should” proceed. Young adults often have limited experience with serious illness so are unable to rely on previous experiences or established coping strategies. Finally, young adults feel isolated during cancer treatment, report dissatisfaction with their peer support, and experience reductions in the size of their support networks over time.5 Poor social support is associated with increased risk for suicidal ideation in older patients admitted to general medical units6 and healthy young adults.7

The therapeutic alliance between a patient and provider has been cited as an important factor in the treatment of suicidal patients.8 Therapeutic alliance is the “collaborative and affective bond (p. 438)”9 between a patient and provider.10 The alliance has been called the “quintessential integrative variable” (p. 449)11 in psychotherapy because it is consistently among the most important influences on outcomes.12 Although less is known about the relationship between the patient and oncologist, a stronger alliance in this context has been linked to better quality of life and greater illness acceptance.10 In prospective analyses, the patient-oncologist alliance four months before death was one of the top nine predictors of quality of life in the last week of life in older adults.13 A strong therapeutic alliance is also associated with a lower likelihood of receiving care in the ICU in the last week of life.10

The patient-oncologist alliance may be particularly important for young adults with cancer. A recent study found therapeutic alliance between young adult cancer patients and oncologists was associated with better treatment adherence and psychosocial adjustment.14 Adolescents and young adults rank “availability of health providers who know about treating young adults with cancer” as their second most important healthcare need (p. 141).15 Yet, approximately one-third of adolescents and young adults report an unmet need for approachable healthcare providers.16

This study examines the relationship between the patient-oncologist alliance and suicidal ideation in young adults with advanced cancer, controlling for established predictors of suicidal ideation. This study also examines the relationship between therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation controlling for healthcare services designed to treat psychosocial distress. We hypothesize that a strong therapeutic alliance will be associated with a reduced risk of suicidal ideation. In addition, we hypothesize that this relationship will remain significant after controlling for mental health service use.

Methods

Patients and Procedures

Eligible patients were identified through electronic medical record review at a single tertiary cancer care center. Eligible patients were 20-40 years of age and had a diagnosis of incurable, recurrent, or metastatic cancer (i.e., “advanced cancer”). Patients were excluded if they were not fluent in English, were too weak to complete the interview per oncologist report, and/or had scores of 5 or greater on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire indicating cognitive impairment likely to invalidate a patient’s responses. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board and all enrolled patients provided written informed consent.

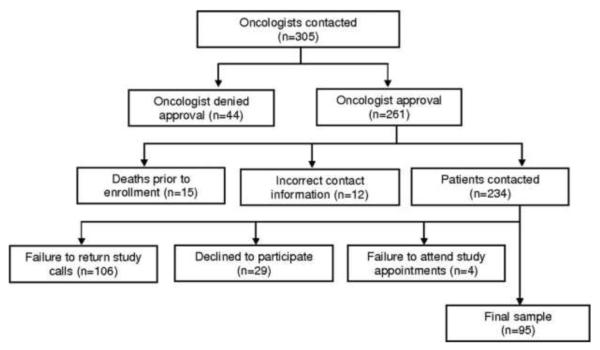

Oncologists for 305 patients were contacted to request permission to recruit patients for the study; 261 (86%) were approved for contact. Of those, 15 patients died prior to study enrollment and 12 had incorrect contact information. Of the 234 patients contacted, 106 (45%) failed to return study calls, 4 (1.7%) scheduled interviews but did not attend, and 29 (12%) declined participation. Ninety-five patients completed study procedures, resulting in a participation rate of 41% (see Figure 1). Two patients provided incomplete data on the suicidality measure and were not included in analyses, leading to a final sample of n=93. These patients had 49 unique primary oncologists.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for participant recruitment

Graduate-level trained assessors conducted face-to-face interviews between April 2010 and May 2012. Interviews lasted 50-90 minutes. Patients were compensated $25.

Measures

Demographic and Disease Characteristics

Demographic characteristics were based on participant self-report and included age, gender, race, marital status, parental status, education level, health insurance status, and income. Disease characteristics were obtained from patients’ medical records and included cancer diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, presence of metastatic disease, time since diagnosis, whether the patient’s treatment included pain management, and whether the patient was participating in a drug trial.

Suicidal Ideation

The Yale Evaluation of Suicidality (YES) is a 16-item measure that assesses current suicidal thoughts and actions, history of suicide attempts, and protective factors. The YES has been validated in adults with advanced cancer.17 The first 4 items of the YES are a screening measure (Cronbach’s α = .67) and were used to assess suicidal ideation in this study. Patients’ scores on the screening items were dichotomized where positive screen (endorsement of any item) = 1 and negative screen = 0.

Therapeutic Alliance

The Human Connection scale (THC) is a 16-item measure of the alliance between a patient and oncologist (current sample: Cronbach’s alpha=.89).10 The THC has been validated in older patients with advanced cancer.10 Due to a negative skew, the THC was dichotomized into the upper third (strong=1) and lower two-thirds (weak=0) of the sample.

Psychiatric Disorders

The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID) Axis I modules18 were used to diagnose major depressive disorder (MDD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the past month.

Performance Status

Physical performance status was assessed with the Karnofsky Performance Scale, a clinician rating scale from zero (death) to 100 (normal; no evidence of disease) completed by a trained study interviewer.19

Physical Quality of Life

The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL) is a 16-item self-report measure of quality of life over the previous two days that has been validated in individuals with life-threatening illness.20 The one-item physical well-being subscale was used to assess physical quality of life. The item is rated on an 11-point scale with higher scores indicating better physical well-being.

Social Support

The two-item social support subscale of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire was used to assess perceived social support (Cronbach’s α = .82). Each item is rated on an 11-point scale with higher scores indicating greater perceived support.

Number of Physical Symptoms

Patients reported whether they were bothered by each of 11 symptoms over the previous two days (no=0, yes=1). Symptoms included pain, tiredness, weakness, nausea, vomiting, lack of appetite, trouble sleeping, shortness of breath, constipation, diarrhea, and sweating. Patients were also asked to identify other bothersome symptoms not included in the list for a maximum of 12 symptoms. The number of symptoms reported was summed to create a total score.

Mental Health Service Use

Patients indicated whether they discussed mental health concerns with various healthcare professionals since being diagnosed with cancer (“Have you discussed mental health concerns with a professional since the time you were diagnosed with cancer;” no=0, yes=1). Providers included an oncology social worker, other oncology clinic staff, a mental health professional, clergy, and a palliative care doctor. Patients also indicated whether they had accessed various mental health interventions since their cancer diagnosis (No=0, Yes=1). Mental health interventions assessed included psychotherapy, antidepressant medication, anxiolytic medication, antipsychotic medication, visits with clergy, and support groups.

Statistical Analysis

Relationships between suicidal ideation and sample characteristics (i.e., disease and demographic characteristics) and mental health service use were examined using logistic regression analyses predicting suicidal ideation. Multivariable logistic regression analyses then regressed suicidal ideation on therapeutic alliance and included demographic and disease characteristics, indicators of mental health, and measures of social support and physical well-being significantly associated (p≤.05) with suicidal ideation. To identify the aspects of therapeutic alliance associated with suicidal ideation, logistic regression analyses were conducted regressing suicidal ideation on each item of The Human Connection Scale with a separate model for each item. The bivariate relationship between mental health discussions with each type of healthcare provider and utilization of specific mental health interventions and suicidal ideation were examined using logistic regression models. Finally, adjusted analyses of the relationship between therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation controlling for mental health service use were conducted using two separate logistic regression models. The first model controlled for mental health discussions with healthcare providers. The second model controlled for utilization of mental health interventions. An alpha level of p≤.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance for all analyses and all results were two-sided.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. The sample was primarily white (87·1%) and female (68.8%) with a mean age of 33.3 years (SD=5·.53). Approximately half of the sample was married (58.1%) and over one-third had dependent children (39.8%). One-third of the sample was breast cancer patients (34.4%). Mean time since initial diagnosis was 3.45 years (SD = 3.01). All patients had advanced disease at the time of the interview. Over one-fifth of the sample (22.6%) screened positive for suicidal ideation on the four-item measure.

Table 1.

Background characteristics and suicidal ideation

| All Participants | Suicidal Ideation, N (%) | Logistic Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N = 93; N(%)a | Positive, 21 (22.6) | Negative, 72 (77.4) | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Gender | 2.54 (.93, 6.92) | .07 | |||

| Female | 64 (68.8) | 11 (17.2) | 53 (82.8) | ||

| Male | 29 (31.2) | 10 (34.5) | 19 (65.5) | ||

| Raceb | 2.90 (.81, 10.35) | .10 | |||

| White | 81 (87.1) | 16 (19.8) | 65 (80.2) | ||

| African American | 3 (3.2) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Asian-American/Pacific Islander/Indian |

4 (4.3) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Hispanic | 5 (5.4) | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | ||

| Marital Status | 1.05 (.39, 2.81) | .92 | |||

| Married | 54 (58.1) | 12 (22.2) | 42 (77.8) | ||

| Other | 39 (41.9) | 9 (23.1) | 30 (76.9) | ||

| Dependent Children | .91 (.34, 2.48) | .86 | |||

| Yes | 37 (39.8) | 8 (21.6) | 29 (78.4) | ||

| No | 56 (60.2) | 13 (23.2) | 43 (76.8) | ||

| Health Insurancec | |||||

| Yes | 91 (97.8) | 21 (23.1) | 70 (76.9) | ||

| No | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100) | ||

| Incomed | .48 (.18, 1.31) | .15 | |||

| $0- $10,999 | 2 (2.2) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| $11,000-20,999 | 6 (6.5) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | ||

| $21,000-30,999 | 5 (5.4) | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | ||

| $31,000-50,999 | 8 (8.6) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | ||

| $51,000-99,999 | 32 (43.4) | 7 (21.9) | 25 (78.1) | ||

| $100,000 or more | 29 (31.2) | 4 (13.8) | 25 (86.2) | ||

| Don’t Knowe | 11 (11.8) | 2 18.2) | 9 (81.8) | ||

|

| |||||

| N(%) | Positive | Negative | OR (95% CI) | p | |

|

| |||||

| Cancer Diagnosisf | .25 (.07, .92) | .04 | |||

| Breast | 32 (34.4) | 3 (9.4) | 29 (90.6) | ||

| Lung (non-small cell) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | ||

| Pancreatic | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | ||

| Colon | 4 (4.3) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||

| Brain Tumor | 15 (16.1) | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | ||

| Stomach | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | ||

| Esophageal | 1 (1.1) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Bone | 2 (2.2) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| Soft Tissue | 8 (8.6) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | ||

| Leukemia/ Lymphoma | 10 (10.8) | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | ||

| Other | 18 (19.4) | 4 (22.2) | 14 (77.8) | ||

| Stage at diagnosisg | .62 (.16, 2.40) | .49 | |||

| I | 5 (5.4) | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | ||

| II | 10 (10.8) | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | ||

| III | 24 (25.8) | 4 (16.7) | 20 (83.3) | ||

| IV | 25 (26.9) | 5 (20.0) | 20 (80.0) | ||

| Unknowne | 29 (31.2) | ||||

| Metastasis | 1.23 (.46, 3.25) | .68 | |||

| Yes | 48 (51.6) | 10 (20.8) | 38 (79.2) | ||

| No | 45 (48.4) | 11 (24.4) | 34 (75.6) | ||

| Drug Trial | .97 (.33, 2.85) | .96 | |||

| Yes | 27 (29.0) | 6 (22.2) | 21 (77.8) | ||

| No | 66 (71.0) | 15 (22.7) | 51 (77.3) | ||

| MDD – current | 6.40 (1.60, 25.55) | .01 | |||

| Yes | 10 (11.0) | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | ||

| No | 81 (89.0) | 15 (19.0) | 64 (81.0) | ||

| PTSD – current | |||||

| Yes | 7 (7.4) | 4 (57.1%) | 3 (42.9) | 5.02 (1.02, 24.61) | <.05 |

| No | 82 (92.1) | 17 (21.0) | 64 (79.0) | ||

|

| |||||

| N(%) | Positive | Negative | OR (95% CI) | p | |

|

| |||||

| Pain Management | 1.52 (.50, 4.59) | .46 | |||

| Yes | 21 (22.6) | 6 (28.6) | 15 (71.4) | ||

| No | 72 (77.4) | 15 (20.8) | 57 (79.2) | ||

| Therapeutic Alliance with oncologisth | .26 (.07, .97) | <.05 | |||

| Weak | 64 (67.4) | 18 (29.0) | 44 (71.0) | ||

| Strong | 31 (32.6) | 3 (9.7) | 28 (90.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| All Participants | Suicidal Ideation, Mean (SD) | Logistic Regression | |||

|

| |||||

| Mean (SD) | Positive | Negative | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age, years | 33.31 (5.53) | 32.24 (6.08) | 33.63 (5.37) | .96 (.88, 1.04) | .31 |

| Education | 15.94 (2.51) | 15.62 (2.38) | 16.03 (2.55) | .94 (.76, 1.14) | .51 |

| Years since diagnosis | 3.45 (3.01) | 3.28 (2.30) | 3.50 (3.20) | .98 (.83, 1.15) | .77 |

| Performance Status | 80.11 (11.18) | 74.29 (13.63) | 81.81 (9.83) | .94 (.90, .99) | .01 |

| Physical quality of life | 6.84 (2.49) | 5.62 (2.91) | 7.20 (2.45) | .78 (.64, .95) | .01 |

| Number of physical symptoms | 3.94 (2.54) | 5.10 (2.30) | 3.60 (2.53) | 1.26 (1.03, 1.54) | .02 |

| Social Support | 16.41 (3.95) | 15.24 (4.56) | 16.69 (3.76) | .92 (.82, 1.03) | .15 |

Note. Gender (0=Female, 1=Male), Marital status (Married=0, Other=1), Dependent children (No=0, Yes=1), Metastasis (Yes=0, No=1), Drug trial (Yes=0, No=1), MDD - current (0=Negative diagnosis, 1=Positive diagnosis), ), PTSD – current (0=Negative diagnosis, 1=Positive diagnosis), Pain Management (0=No, 1=Yes);.

Variations in sample size are due to missing data.

Dichotomized into White=0, Other=1 for analyses.

Comparative analyses were not conducted for health insurance status due to low rates of uninsured.

Dichotomized into ≤$50,999=0, ≥$51,000=1

Excluded from analyses.

Dichotomized into Other=0, Breast=1 for analyses.

Dichotomized into Stage 1 and 2=0; Stage 3 and 4=1.

Dichotomized where the upper third of the sample was strong (1) and the lower (0) two-thirds was weak based on scores on The Human Connection Scale.

Associations of sample characteristics with suicidal ideation are shown in Table 1. Patients with a breast cancer diagnosis were at reduced risk for suicidal ideation relative to patients with non-breast cancer primary diagnoses (OR, .25 [95% CI, .07, .92]). Better performance status (OR, .94 [95% CI, .90, .99]) and physical quality of life (OR, .78 [95% CI, .64, .95]) were associated with a lower risk of suicidal ideation. In addition, patients with a greater number of physical symptoms were at increased risk for suicidal ideation (OR, 1.26 [95% CI, 1.03, 1.54]). Finally, patients with current MDD (OR, 6.40 [95% CI, 1.60, 25.55]) or PTSD (OR, 5.02 [95% CI, 1.02, 24.61]) were at increased risk for suicidal ideation. No additional significant relationships among sample characteristics and suicidal ideation emerged.

Therapeutic Alliance

In unadjusted analyses, patients with a strong therapeutic alliance were at reduced risk for suicidal ideation relative to patients with a weak therapeutic alliance (see Table 1; OR, .26 [95% CI, .07, .97]). Logistic regression analyses of the relationship between therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation controlling for sample and disease characteristics, MDD, PTSD, and physical well-being are shown in Table 2. The relationship between therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation remained significant after controlling for these confounding factors (OR, .16 [95% CI, .03, .91]). Despite a nonsignificant bivariate relationship with suicidality, social support was added to the model to examine whether therapeutic alliance was merely an indicator of support. Therapeutic alliance remained a significant predictor of suicidality after adding social support to the model (OR, .13 [95% CI, .02, .85]).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analyses adjusting for all significant bivariate correlates of suicidal ideation

| Suicidal Ideation (0=Negative; 1=Positive) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p |

| Cancer diagnosis | .43 (.09, 2.08) | .30 |

| Performance status | .95 (.89, 1.02) | .17 |

| Number of physical symptoms | .96 (.71, 1.31) | .82 |

| Physical quality of life | .80 (.59, 1.09) | .16 |

| MDD – current | 3.89 (.54, 28.12) | .18 |

| PTSD – current | 1.49 (.17, 12.81) | .72 |

| Therapeutic alliance with oncologist | .16 (.03, .91) | .04 |

Note. Cancer diagnosis (0=Other ,1=Breast), MDD – current (0=Negative diagnosis, 1=Positive diagnosis), PTSD – current (0=Negative diagnosis, 1=Positive diagnosis),Therapeutic alliance (0=weak, 1=strong).

Six items from the Human Connection Scale were significantly associated with suicidal ideation: your oncologist takes the time to listen to your concerns (OR, .43 [95% CI, .18, 1.00], p=.05), you understand your oncologist’s explanations and suggestions (OR, .34 [95% CI, .15, .78], p<.05), your oncologist offers hope (OR, .52 [95% CI, .30, .91], p<.05), your oncologist asks how you are coping with cancer (OR, .59 [95% CI, .36, .97], p<.05), your oncologist is concerned about your quality of life (OR, .47 [95% CI, .23, .97], p<.05), and your oncologist is open-minded (OR, .38 [95% CI, .19, .75], p<.01; Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analyses of the relationship between items on the Human Connection Scale and suicidal ideation

| Suicidal Ideation (0=Negative; 1=Positive) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p |

| How often would you say your doctor takes the time to listen to your concerns? | .43 (.18, 1.00) | .05 |

| To what extent does your doctor pay close attention to what you are saying? | .66 (.26, 1.67) | .38 |

| To what extent do you think your oncologist sees you as a whole person? | .73 (.32, 1.63) | .44 |

| How much do you like your oncologist? | .59 (.27, 1.29) | .19 |

| How much do you trust your oncologist? | .67 (.30, 1.48) | .32 |

| How thorough is your oncologist? | .84 (.37, 1.94) | .69 |

| How much do you respect your oncologist? | .63 (.25, 1.60) | .34 |

| How much do you feel your oncologist cares about you? | .52 (.26, 1.05) | .07 |

| How much of the time would you say your oncologist is honest with you? | 1.12 (.33, 3.82) | .86 |

| To what extent do you feel comfortable asking your oncologist questions? | .39 (.14, 1.06) | .07 |

| How often do you understand your oncologist’s explanations and suggestions? | .34 (.15, .78) | .01 |

| How often does your oncologist ask how family members are coping with your illness? | .81 (.48, 1.36) | .42 |

| How often does your oncologist offer hope? | .52 (.30, .91) | .02 |

| How often does your oncologist ask how you are coping with cancer? | .59 (.36, .97) | .04 |

| How concerned do you think your oncologist is about your quality of life? | .47 (.23, .97) | .04 |

| How open-minded do you feel your oncologist is? | .38 (.19, .75) | .01 |

Therapeutic Alliance and Mental Health Service Use

The bivariate associations of mental health service use with suicidal ideation are shown in Table 4. No significant relationships between mental health discussions with healthcare providers or utilization of mental health interventions and suicidal ideation emerged.

Table 4.

Unadjusted logistic regression analyses of mental health service utilization and suicidal ideation

| All Participants | Suicidal Ideation, N (%) | Logistic Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 93; N(%) | Positive | Negative | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Healthcare Provider | |||||

| Oncology Social Worker | 1.63 (.60, 4.39) | .34 | |||

| Yes | 49 (52.7) | 13 (26.5) | 36 (73.5) | ||

| No | 44 (47.3) | 8 (18.2) | 36 (81.8) | ||

| Other Oncology Clinic Staff | 1.75 (.60, 5.07) | .30 | |||

| Yes | 23 (24.7) | 7 (30.4) | 16 (69.6) | ||

| No | 70 (75.3) | 14 (20.0) | 56 (80.0) | ||

| Mental Health Professional | 1.63 (.61, 4.33) | .33 | |||

| Yes | 40 (43.0) | 11 (27.5) | 29 (72.5) | ||

| No | 53 (57.0) | 10 (18.9) | 43 (81.1) | ||

| Clergy | 2.50 (.72, 8.68) | .15 | |||

| Yes | 13 (14.0) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | ||

| No | 80 (86.0) | 16 (20.0) | 64 (80.0) | ||

| Palliative Care Doctor | .46 (.05, 4.00) | .49 | |||

| Yes | 8 (8.6) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | ||

| No | 85 (91.4) | 20 (23.5) | 65 (76.5) | ||

|

| |||||

| Psychosocial Intervention | All Participants | Suicidal Ideation, N (%) | Logistic Regression | ||

| N (%) | Positive | Negative | OR (95% CI) | p | |

|

| |||||

| Psychotherapy | .79 (.28, 2.19) | .64 | |||

| Yes | 35 (37.6) | 7 (20.0) | 28 (80.0) | ||

| No | 58 (62.4) | 14 (24.1) | 44 (75.9) | ||

| Antidepressants | 2.43 (.87, 6.74) | .09 | |||

| Yes | 26 (28.0) | 9 (34.6) | 17 (65.4) | ||

| No | 67 (72.0) | 12 (17.9) | 55 (82.1) | ||

| Anxiolytics | 1.11 (.42, 2.98) | .83 | |||

| Yes | 38 (40.9) | 9 (23.7) | 29 (76.3) | ||

| No | 55 (59.1) | 12 (21.8) | 43 (78.2) | ||

| Antipsychotics | 3.55 (.21, 59.31) | .38 | |||

| Yes | 2 (2.2) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| No | 91 (97.8) | 20 (22.0) | 71 (78.0) | ||

| Visits with Clergy | 2.59 (.66, 10.22) | .18 | |||

| Yes | 10 (10.8) | 4 (40.0) | 6 (60.0) | ||

| No | 83 (89.2) | 17 (20.5) | 66 (79.5) | ||

| Participation in Support Groups | 1.56 (.48, 5.09) | .46 | |||

| Yes | 17 (18.3) | 5 (29.4) | 12 (70.6) | ||

| No | 76 (81.7) | 16 (21.1) | 60 (78.9) | ||

Note. Healthcare providers (No=0, Yes=1), Psychosocial intervention (No=0, Yes=1), Suicidal ideation (Negative=0, Positive=1).

Logistic regression analyses of the relationship between therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation controlling for mental health service use are shown in Table 5. Patients with a strong therapeutic alliance were at reduced risk for suicidal ideation after controlling for mental health discussions with healthcare providers (OR, .25 [95% CI, .06, .97]). Similarly, after controlling for utilization of mental health interventions, therapeutic alliance remained significantly associated with suicidal ideation (OR, .22 [95% CI, .05, .93]). Use of antidepressant medications was the only mental health intervention significantly associated with suicidal ideation in adjusted analyses (OR, 7.06 [95% CI, 1.35, 36.97]). Patients who were using antidepressant medication were at increased risk for suicidal ideation relative to patients not using antidepressant medication.

Table 5.

Logistic regression analyses adjusting for mental health service utilization

| Suicidal Ideation (0=Negative; 1=Positive) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Healthcare providers | ||

| Oncology social worker | 1.73 (.57, 5.24) | .34 |

| Other oncology clinic staff | 1.21 (.37, 4.00) | .75 |

| Mental health professional | 1.20 (.38, 3.82) | .76 |

| Clergy | 2.24 (.54, 9.37) | .27 |

| Palliative care doctor | .52 (.05, 5.45) | .59 |

| Therapeutic alliance with oncologist | .25 (.06, .97) | <.05 |

|

| ||

| Suicidal Ideation (0=Negative; 1=Positive) |

||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | |

|

| ||

| Psychosocial intervention | ||

| Psychotherapy | .36 (.08, 1.56) | .17 |

| Antidepressants | 7.06 (1.35, 36.97) | .02 |

| Anxiolytics | .47 (.12, 1.89) | .29 |

| Antipsychotics | 1.91 (.09, 41.37) | .68 |

| Visits with clergy | 2.25 (.44, 11.65) | .33 |

| Participation in support groups | 1.50 (.35, 6.44) | .58 |

| Therapeutic alliance with oncologist | .22 (.05, .93) | <.05 |

Note. Psychosocial providers (No=0, Yes=1), Psychosocial services (No=0, Yes=1), Therapeutic alliance (1=strong, 0=weak).

Based on these results, we conducted additional analyses to examine the influence of MDD on the relationship between antidepressant medication use and suicidal ideation. First, MDD was added to the model predicting suicidal ideation with utilization of mental health interventions. Therapeutic alliance (OR, .20 [95% CI, .04, .97]) remained a significant predictor of suicidal ideation in this model (OR, 9.79 [95% CI, 1.71, 56.11]). Antidepressant use was no longer a significant predictor in this model (OR, 5.27 [95% CI, .94, 29.63]). Second, we examined the relationship between suicidal ideation and the interaction of MDD and antidepressant use, using Chi-Square analyses. The interaction was significantly associated with suicidal ideation (see Table 6; χ2(3, 89)=9.40, p=.02). Pair-wise comparisons indicated that patients with MDD who were taking an antidepressant were at increased risk for suicidal ideation relative to patients without MDD who were not taking antidepressant medication (p=.012). No other significant group differences emerged.

Table 6.

Interaction of major depressive disorder and anti-depressant use with suicidal ideation

| All Participants | Suicidal Ideation, N (%) | χ 2 (df) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N (%) | Positive, 21 | Negative, 72 | |||

| MDD × AD use | 9.40 (3) | .02 | |||

| No MDD/No AD | 60 (67.4) | 10 (16.7) | 50 (83.3)* | ||

| No MDD/AD | 19 (21.3) | 5 (26.3) | 14 (73.7) | ||

| MDD/No AD | 4 (4.5) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||

| MDD/AD | 6 (6.7) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3)* | ||

Note. indicates significant group differences; MDD=Major Depressive Disorder; AD=Antidepressant use.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between the patient-oncologist therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation in young adults with advanced cancer. A strong therapeutic alliance was associated with reduced risk for suicidal ideation, after controlling for confounding sample characteristics, indicators of physical health, MDD, and PTSD. This finding is consistent with previous research on therapeutic alliance and psychosocial distress in older adult advanced cancer patients10 and young adults with advanced cancer.14 In separate analyses, therapeutic alliance remained a significant predictor of suicidal ideation after controlling for mental health discussions with healthcare providers and utilization of mental health interventions.

This study is the first to examine the patient-oncologist alliance and suicidal ideation. Notably, the relationship between therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation remained significant after controlling for well-established predictors of suicidal ideation.4 Thus, the alliance with the oncologist appears to be important to the experience of suicidal ideation in young adults with advanced cancer, independent of young adults’ physical and mental health status. In addition, therapeutic alliance remained a significant predictor of suicidality after controlling for social support, providing additional evidence of the unique importance of patients’ relationships with their oncologist as protection against suicidality. This study also offers insight into the aspects of therapeutic alliance most relevant to suicidal ideation. The results suggest that an effective therapeutic alliance is multi-dimensional and includes communication strategies such as listening and providing clear explanations, expressions of concern for the patient’s well-being, positivity, and openness. Oncologists working to build a strong therapeutic alliance with their patients may benefit from attention to these aspects of their relationships with their patients.

The relationship between therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation was also significant after controlling for utilization of mental health services. Oncologists may offer a unique protective factor that is not accounted for by mental health interventions. Many cancer patients do not seek mental health services and do not receive adequate treatment for mental illness.21 In addition, the availability of mental health resources varies across settings; some cancer patients may not have access to mental health services. Young adults may be particularly vulnerable to underutilization of mental health resources due to higher rates of uninsurance,22 a desire to maintain normalcy,23 and worries about the stigma associated with receipt of mental health care. Therefore, a strong therapeutic alliance between the patient and oncologist may be a valuable resource for preventing and reducing suicidal ideation.

With the exception of antidepressant use, discussions with mental health providers and utilization of mental health interventions were not associated with suicidal ideation. In the context of cancer, young adults may focus on their relationship with the oncologist and may view distress due to cancer as under the purview of the oncologist. These results suggest that referral to a mental health provider may be indicated but insufficient to address suicidal ideation in this population.

In adjusted analyses, utilization of antidepressant medications was associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation in this sample. Antidepressant medications carry a black box warning regarding increased risk for suicidal ideation in young patients24 and we cannot rule out the possibility that antidepressants heightened suicidal ideation in this sample. However, only patients with MDD who were taking an antidepressant were at increased risk for suicidal ideation. Patients who did not meet diagnostic criteria for MDD and who were taking antidepressant medication were not at increased risk for suicidal ideation, suggesting that antidepressant use did not increase the risk for suicidal ideation. Patients experiencing MDD with suicidal ideation may be experiencing the greatest distress and, as a result, be more likely to receive an antidepressant. Longitudinal analyses with a larger sample are needed to determine the causal relationships between antidepressant use and suicidality among young adult cancer patients.

Developing a strong therapeutic alliance can be a difficult task that is further complicated by the unique developmental issues of young adulthood. Building a strong alliance with young adult cancer patients requires consideration of the maturity level, independence, and cognitive and emotional development of the patient.25 Training in the developmental characteristics of young adults may help oncologists strengthen the therapeutic alliance. In addition, effective communication styles with young adults are direct, respectful, non-judgmental, and avoid punitive and over-controlling communication styles.23 Research suggests that positive talk and discussing psychosocial issues are related to a stronger alliance.26 However, additional research is needed to clarify the relationship between communication training, therapeutic alliance, and suicidal ideation. Finally, guidelines for developing an effective therapeutic alliance with pediatric cancer patients have been published.27 These guidelines define the role of the healthcare team and family members in the therapeutic alliance and provide recommendations for promoting an effective relationship between a family and a healthcare team. Similar guidelines for young adult patients may be a valuable tool for oncologists that improves patient care and reduces young adults’ risk for suicidal ideation.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study was limited by a relatively small sample and cross-sectional data which limit the generalizability of study findings and preclude statements of causality. In addition, the sample for this study was restricted to young adults with advanced disease. Research indicates that patients are at increased risk for suicidal ideation in the 1-3 months following diagnosis28 and following hospital discharge.29 Examination of the relationship between therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation across illness trajectory may be important. The inclusion criterion of advanced disease likely explains this study’s low response rate (41%). Anecdotally, the most common reason provided by oncologists for not including patients in the study was poor physical health. Future studies should consider data collection methods such as electronic questionnaires that may be less burdensome for patients with advanced disease and may lead to a more representative sample. Finally, the sample included a broad age range to capture NCI-defined “young adults.”30 This range, however, captures multiple developmental transitions. In particular, normal development of the cognitive ability to engage in abstract thinking, planning, and decision-making continues into young adulthood whereas areas of the brain that respond to motivational and emotional cues develop at an earlier age.31 This developmental trajectory may increase young adults’ risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors. Examination of suicidal ideation in various age groups within young adulthood is important to clarify the role of the patient-oncologist alliance across young adulthood.

Acknowledgments

Funding: MH63892, CA106370, CA156732

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Misono S, Weiss NS, Fann JR, Redman M, Yueh B. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Oct 10;26(29):4731–4738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker J, Waters RA, Murray G, et al. Better off dead: suicidal thoughts in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Oct 10;26(29):4725–4730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.8844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miniño AM, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2008. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Druss B, Pincus H. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in general medical illnesses. Arch Intern Med. 2000 May 22;160(10):1522–1526. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishibashi A. The needs of children and adolescents with cancer for information and social support. Cancer Nurs. 2001 Feb;24(1):61–67. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200102000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furlanetto LM, Stefanello B. Suicidal ideation in medical inpatients: psychosocial and clinical correlates. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011 Nov;33(6):572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilcox HC, Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Pinchevsky GM, O’Grady KE. Prevalence and predictors of persistent suicide ideation, plans, and attempts during college. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;127(1-3):287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michel K, Jobes DA. Building a therapeutic alliance with the suicidal patient. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC US: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(3):438–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mack JW, Block SD, Nilsson M, et al. Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: the Human Connection Scale. Cancer. 2009 Jul 15;115(14):3302–3311. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfe BE, Goldfried MR. Research on psychotherapy integration: recommendations and conclusions from an NIMH workshop. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988 Jun;56(3):448–451. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horvath AO, Bedi RP. The alliance. In: Norcross JC, editor. Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients. Oxford University Press; New York, NY US: 2002. pp. 37–69. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang B, Nilsson ME, Prigerson HG. Factors Important to Patients’ Quality of Life at the End of Life. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Jul 9;:1–10. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trevino KM, Fasciano K, Prigerson HG. Patient-oncologist alliance, psychosocial well-being, and treatment adherence among young adults with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013 May 1;31(13):1683–1689. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.7993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zebrack BJ, Mills J, Weitzman TS. Health and supportive care needs of young adult cancer patients and survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2007 Jun;1(2):137–145. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millar B, Patterson P, Desille N. Emerging adulthood and cancer: how unmet needs vary with time-since-treatment. Palliat Support Care. 2010 Jun;8(2):151–158. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer RJ, Ray A, Pirl WF, Prigerson HG. Clinical Correlates of Suicidal Thoughts in Patients With Advanced Cancer. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011 Oct 10; doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318233171a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.First M, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorders – Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0): Biometrics Research Department. New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mor V, Laliberte L, Morris JN, Wiemann M. The Karnofsky Performance Status Scale. An examination of its reliability and validity in a research setting. Cancer. 1984 May 1;53(9):2002–2007. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840501)53:9<2002::aid-cncr2820530933>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Bruera E, Provost M, Rowe J, Tong K. Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: a multi-centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliat Med. 1997 Jan;11(1):3–20. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisch MJ, Titzer ML, Kristeller JL, et al. Assessment of quality of life in outpatients with advanced cancer: the accuracy of clinician estimations and the relevance of spiritual well-being--a Hoosier Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jul 15;21(14):2754–2759. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen R, Martines ME. Health insurance coverage: Early release of estimates from the National Health Interivew Survey, January - March 2012. Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Agostino NM, Penney A, Zebrack B. Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011 May 15;117(10 Suppl):2329–2334. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Revisions to product labeling. FDA; Rockville, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrari A, Thomas D, Franklin AR, et al. Starting an adolescent and young adult program: some success stories and some obstacles to overcome. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Nov 10;28(32):4850–4857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meystre C, Bourquin C, Despland JN, Stiefel F, de Roten Y. Working alliance in communication skills training for oncology clinicians: A controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2013 Feb;90(2):233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masera G, Spinetta JJ, Jankovic M, et al. Guidelines for a therapeutic alliance between families and staff: a report of the SIOP Working Committee on Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Oncology. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1998 Mar;30(3):183–186. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199803)30:3<183::aid-mpo12>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang F, Fall K, Mittleman MA, et al. Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012 Apr 5;366(14):1310–1318. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin HC, Wu CH, Lee HC. Risk factors for suicide following hospital discharge among cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2009 Oct;18(10):1038–1044. doi: 10.1002/pon.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group . Closing the Gap: Research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000 Jun;24(4):417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]