Abstract

Background

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death for men and the fifth for women. The standard treatment for resectable tumours consists of a classic Whipple (CW) operation or a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPW). It is unclear which of these procedures is more favourable in terms of survival, mortality, complications and quality of life.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review is to compare the effectiveness of CW and PPW techniques for surgical treatment of cancer of the pancreatic head and the periampullary region.

Search methods

We conducted searches on 28 March 2006, 11 January 2011 and 9 January 2014 to identify all randomised controlled trials (RCTs), while applying no language restrictions. We searched the following electronic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) from The Cochrane Library (2013, Issue 4); MEDLINE (1946 to January 2014); and EMBASE (1980 to January 2014). We also searched abstracts from Digestive Disease Week and United European Gastroenterology Week (1995 to 2010). We identified no additional studies upon updating the systematic review in 2014.

Selection criteria

We considered RCTs comparing CW versus PPW to be eligible if they included study participants with periampullary or pancreatic carcinoma.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data from the included studies. We used a random-effects model for pooling data. We compared binary outcomes using odds ratios (ORs), pooled continuous outcomes using mean differences (MDs) and used hazard ratios (HRs) for meta-analysis of survival. Two review authors independently evaluated the methodological quality and risk of bias of included studies according to the standards of The Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

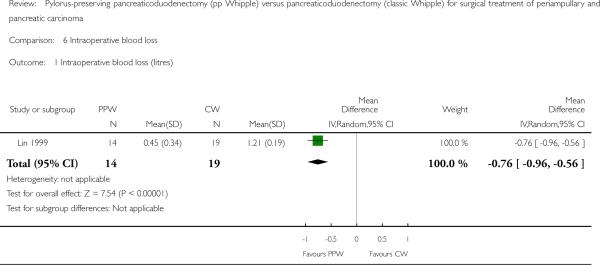

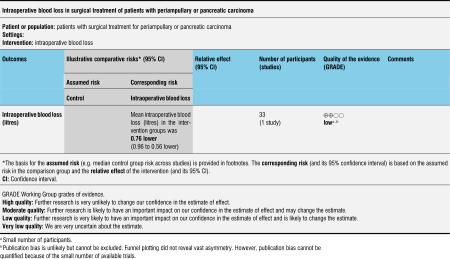

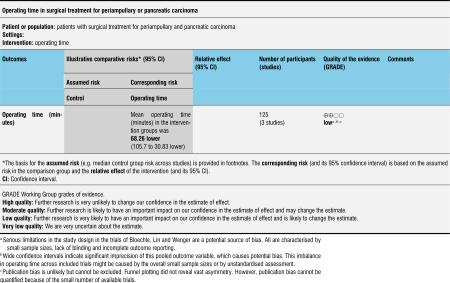

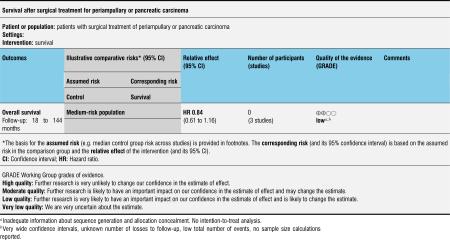

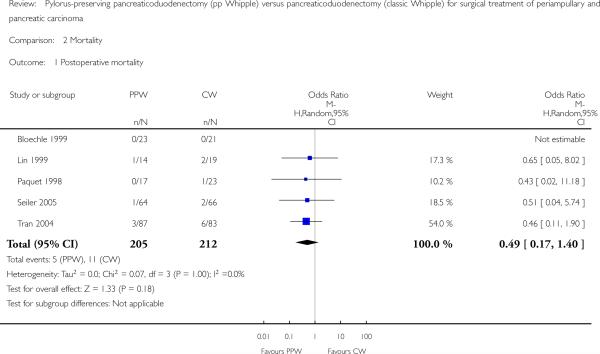

We included six RCTs with a total of 465 participants. Our critical appraisal revealed vast heterogeneity with respect to methodological quality and outcome parameters. In-hospital mortality (OR 0.49, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.17 to 1.40; P value 0.18), overall survival (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.16; P value 0.29) and morbidity showed no significant differences. However, we noted that operating time (MD -68.26 minutes, 95% CI -105.70 to -30.83; P value 0.0004) and intraoperative blood loss (MD -0.76 mL, 95% CI -0.96 to -0.56; P value < 0.00001) were significantly reduced in the PPW group. All significant results are associated with low quality of evidence as determined on the basis of GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) criteria.

Authors’ conclusions

No evidence suggests relevant differences in mortality, morbidity and survival between the two operations. Given obvious clinical and methodological heterogeneity, future research must be undertaken to perform high-quality randomised controlled trials of complex surgical interventions on the basis of well-defined outcome parameters.

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death for men and the fifth leading cause of cancer death for women, accounting for 4.8% of cancer deaths in men and 5.5% in women (Edwards 2002; Jemal 2005). In large series, the aggressive nature of these tumours and the high local recurrence rate, together with early metastatic spread, have resulted in disappointing five-year survival rates of between 11% and 21% after resection (Sperti 1996; Yeo 1995).

Description of the intervention

The current standard therapy for pancreatic tumours situated in the head of the pancreas is resection (Buchler 2003; Lillemoe 2000). Great improvement in pancreatic surgery has led to mortality rates of less than 5% at high-volume centres (Buchler 2003; Trede 1990; Yeo 1997). Moreover, mortality and morbidity rates after resection reached similar levels to those following the palliative bypass operation (Gouma 1999; Koslowsky 2001; Lillemoe 1996). Nevertheless, operative morbidity remains high, occasionally approaching 30% to 40% (Bassi 2001; Gouma 2000; Richter 2003), from causes including intra-abdominal abscess, sepsis, pancreatic fistula and delayed gastric emptying (DGE).

Two surgical techniques are usually performed in the treatment of pancreatic head cancer: the classic Whipple (CW) operation developed by Kausch (Kausch 1912) and later perfected by Whipple (Whipple 1935), and the pylorus-preserving Whipple (PPW) operation inaugurated by Watson (Watson 1944) and popularised by Traverso and Longmire (Traverso 1980).

How the intervention might work

The CW operation consists of an en bloc (as one unit) removal of the pancreatic head, the duodenum, the common bile duct, the gall bladder and the distal portion of the stomach, together with adjacent lymph nodes (Trede 1993). This operation can lead to special complications such as early and late dumping (rapid emptying of the stomach), postoperative weight loss (Seiler 2000) and postoperative reflux (Williamson 1993).

Why it is important to do this review

The PPW operation preserves the stomach and the pylorus, the latter of which is needed for the physiologically timed transport of chyme (partially digested food passing into the intestine). The extent of this resection is obviously less than that of the CW operation; it is therefore expected that operation time will decrease and blood loss will be less. In addition, some authors report improved postoperative weight gain (Seiler 2000), higher quality of life (Wenger 1999) and better access to the biliary anastomosis for postoperative endoscopy in patients with recurrent biliary obstruction. It is unclear whether the lesser extent of the resection is justified if regarded from the oncological side, and whether DGE occurs more often in the PPW procedure than in the CW operation.

OBJECTIVES

The objective of this systematic review is to compare the effectiveness of CW and PPW techniques for surgical treatment of cancer of the pancreatic head and the periampullary region.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) irrespective of publication status or language.

Types of participants

Patients undergoing an elective PPW or CW operation for periampullary or pancreatic carcinoma.

Types of interventions

Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Classic Whipple operation.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Postoperative pancreatic-associated morbidity (disease-specific), such as leakage from the pancreatic anastomosis/pancreatic fistula, DGE and biliary leakage.

Secondary outcomes

Survival.

Postoperative mortality.

Blood loss.

Required blood replacement.

Operation time.

General morbidity, including postoperative gastrointestinal bleeding, wound infection, pulmonary insufficiency, necessity for reoperation.

Duration of hospital stay.

Quality of life.

Status of resection margins (R0/R1* resection).

*R0 means that the tumour is resected without residual microscopic remnants. In an R1 resection, a microscopic remnant of the tumour is present, and in an R2 resection, macroscopic tumour parts can be seen.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted searches on 28 March 2006, 11 January 2011 and 9 January 2014 to identify all published and unpublished RCTs, while applying no language restrictions.

We identified relevant trials by searching the following electronic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) from The Cochrane Library (2013, Issue 4); MEDLINE (1946 to January 2014); and EMBASE (1980 to January 2014). We also handsearched abstracts from the 1995 to 2010 American Digestive Disease Week (DDW), published in Gastroenterology, and the United European Gastroenterology Week (UEGW), published in Gut.

We constructed the search strategy for this review by using a combination of medical subject headings (MeSH) and text words related to the use of pancreaticoduodenectomy or pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy in the surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer. To identify RCTs, we combined the following search with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy phases one, two and three, as contained in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005) (please see Appendix 1).

Searching other resources

We contacted members of the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group and experts in the field and asked them to provide details of outstanding clinical trials and any relevant unpublished materials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently scanned the abstracts of all trials identified by the search to determine eligibility. Each contributor independently evaluated whether trials fulfilled the inclusion criteria. We then selected full articles for further assessment if the abstract suggested that the study was relevant. If these criteria were unclear from the abstract, we retrieved and reviewed the full article for clarification. We excluded papers not meeting our inclusion criteria; these studies are listed along with reasons for their omission in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third review author.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from published and unpublished reports using standardised forms. A list of the data items that we extracted can be found in Appendix 2.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

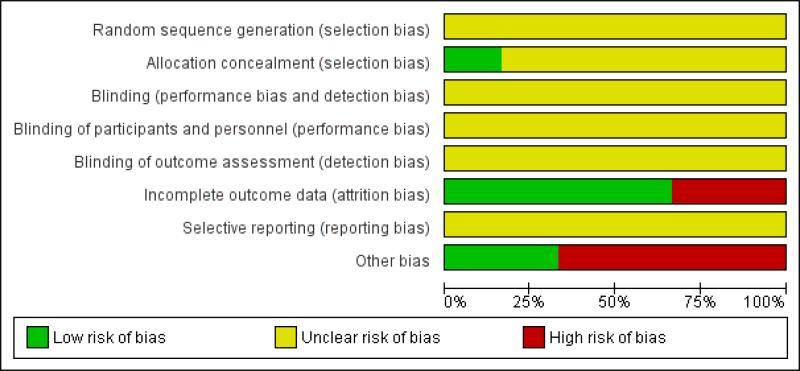

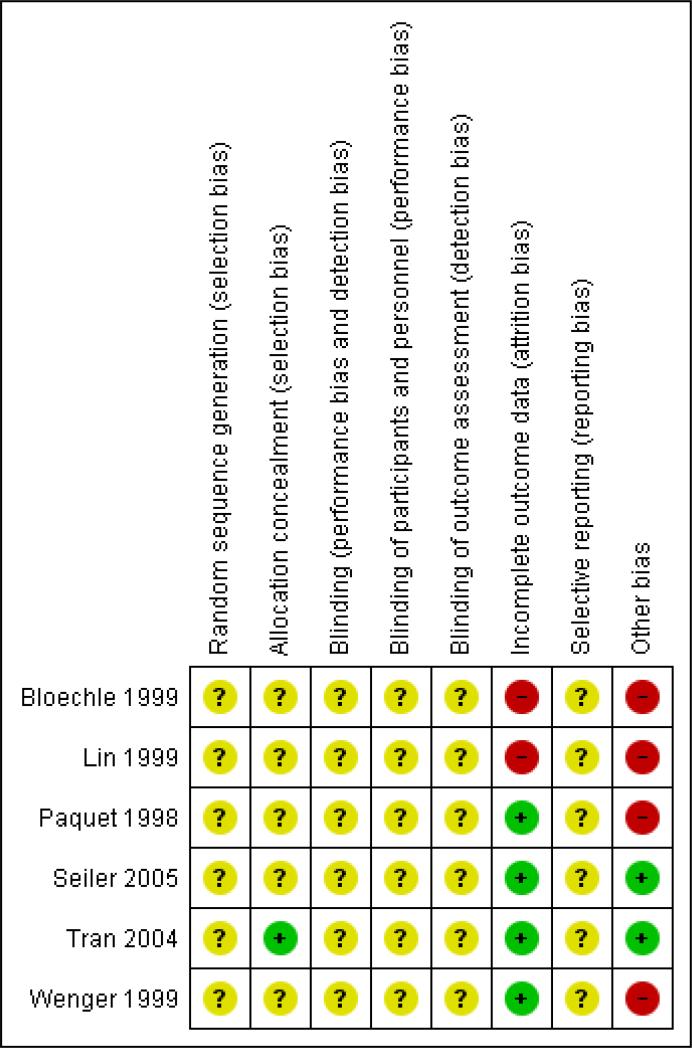

We assessed the methodological quality of the studies. Methodological quality is defined as confidence that the study design and its report will restrict bias in the comparison of interventions (Moher 1998). We assessed methodological quality according to empirical evidence (Jadad 1996; Kjaergard 2001; Moher 1998; Schulz 1995) by examining how the allocation sequence was generated, how allocation concealment was provided and what risks of other bias were present (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

We measured the hazard ratio (HR) and determined the 95% confidence interval (CI) for survival. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the odds ratio (OR) along with 95% CI. For continuous outcomes, we calculated mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was each participant recruited into the trials.

Dealing with missing data

We performed the analysis on an intention-to-treat basis when possible. Otherwise, we adopted the per-protocol analysis as presented in the original trials.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Using the random-effects model (DerSimonian 1986), we calculated pooled estimates of effect and investigated the results for statistical heterogeneity (using the I2 statistic). If an extreme level of heterogeneity was identified, we interpreted summary effect measures with caution. However, we investigated the causes of heterogeneity as far as collected data would allow.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots to explore publication bias (Egger 1997a) and used asymmetry in a funnel plot of trial size against treatment effect to assess bias. We created funnel plots for overall survival, mortality and the most representative cause of postoperative morbidity, which is occurrence of a pancreatic fistula. We planned a test for asymmetry if at least 10 trials were included. Otherwise we used funnel plots for inspection and visual detection of potential publication bias only.

Data synthesis

Additional statistical guidance was provided by the editorial base and the review authors’ host institutions. We ensured data accuracy by performing double data entry. We combined data from different trials reporting the same or similar comparisons. We summarised dichotomous data using odds ratios (ORs), presented continuous data as weighted mean differences (WMDs) and summarised survival or time-to-event data using hazard ratios (HRs). We calculated pooled HRs according to the methods described by Parmar et al (Parmar 1998).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed subgroup analyses for survival in participants with periampullary cancer or pancreatic head cancer and in both groups together, as well as for those with DGE and pancreatic fistula, with regard to different definitions.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis in cases of differing definitions of outcome measures, analysing trials separately that defined outcome measures identically.

RESULTS

Description of studies

Results of the search

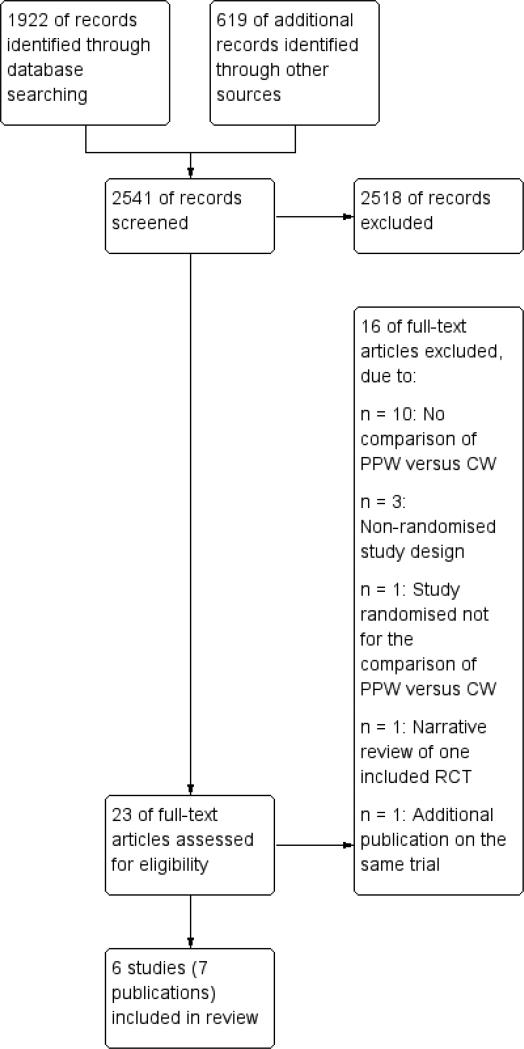

We retrieved 1235 abstracts through the 2006 search, an additional 129 abstracts from the 2011 search and a further 558 abstracts from the most recent search update in 2014. We checked these abstracts for eligibility. The 2006 search produced six randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including data from seven publications, for inclusion, although none were identified in the 2011 or 2014 search. Six hundred nineteen abstracts from Digestive Disease Week and United European Gastroenterology Week (1995 to 2010) were handsearched, but no additional trials were found.

Included studies

Six RCTs (Bloechle 1999; Lin 1999; Paquet 1998; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004; Wenger 1999) were eligible (see Characteristics of included studies). Because the study by Lin et al, published in 2005, is an update of the study performed in 1999, the only analysed data from the older trial involved red blood cell transfusion, because this information was not reported in the later trial (Lin 1999). After this and the per-protocol analysis of six trials were accounted for, the quantitative data from 496 analysed patients comparing PPW (245 participants) and CW (251 participants) procedures were found suitable for the systematic review.

Besides obvious variation in sample sizes (range from 33 (Lin 1999) to 170 (Wenger 1999)), evaluation of study population baseline characteristics revealed adequate consistency: All analysed participants were included because of resectable pancreatic or periampullary cancer. Moreover, four studies (Paquet 1998; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004; Wenger 1999) provided data on resection margin status after PPW or CW, respectively: All studies showed a balanced interstudy and intrastudy distribution of R0 resectionsresections without microscopical tumour remnants (mean R0 re-section was 91% (standard deviation (SD) = 12.4) in the PPW group and 90.4% (SD = 11.2) in the CW group). In addition, we observed a similar distribution of positive lymph node status in three studies (mean positive lymph node status was 54.3% (SD = 6.7) in the PPW group and 60.4% (SD = 10.1) in the CW group) (Seiler 2005; Tran 2004; Wenger 1999).

Regarding perioperative management, we observed non-standardised administration of somatostatin with regard to dosage, route, frequency and duration. Two of the seven RCTs reported the use of octreotide (100 to 200 micrograms) (Seiler 2005; Tran 2004). No information about the application of erythromycin was available. In the trial by Tran et al (Tran 2004), 10 participants in the CW group and nine in the PPW group received postoperative radiochemotherapy, whereas no participants received adjuvant treatment in one trial by Lin et al (Lin 1999). No reports about adjuvant treatment were available for the other trials.

Excluded studies

From the systematic literature search, we retrieved 2541 abstracts. During this process of study selection, we excluded 2518 (1212 + 129 + 558 + 619) screened abstracts. Of the remaining 23 (23 + 0) screened full articles, 16 (16 + 0) did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. Most of the excluded articles did not cover surgical aspects of the comparison of PPW and CW, nor did they provide quantitative data on the prespecified outcome parameters. A study flow diagram is presented in Figure 3. See Characteristics of excluded studies for details.

Figure 3.

Study flow diagram.

Risk of bias in included studies

Our methodological appraisal of the individual studies revealed vast heterogeneity in study design. Only in the two largest trials (130 (Seiler 2005) and 170 (Tran 2004) participants, respectively) was the underlying sample size calculation described. Tran et al stated that at least 65 participants had to be included in each group to show 30% less blood loss and a 20% decrease in operation time in the PPW group, with α = 0.05 and β = 0.05. The study authors regarded this number as sufficient to demonstrate a reduction in hospital stay as well. The power calculation in the trial conducted by Seiler et al indicated that 58 participants needed to be enrolled for each procedure to detect a 25% difference in morbidity, with α = 0.05 and β = 0.2. The number of participants included was not justified in the other five trials.

Statistical analysis was performed in one trial (Tran 2004) according to the intention-to-treat principle; the other trials were analysed per-protocol.

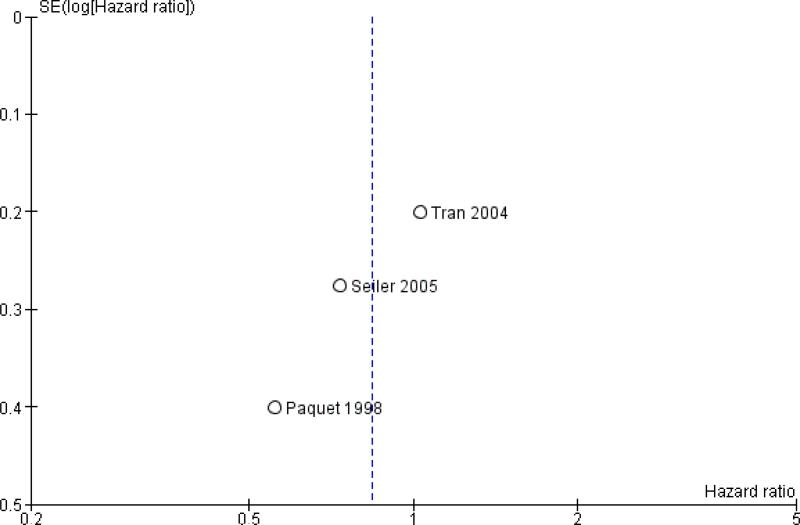

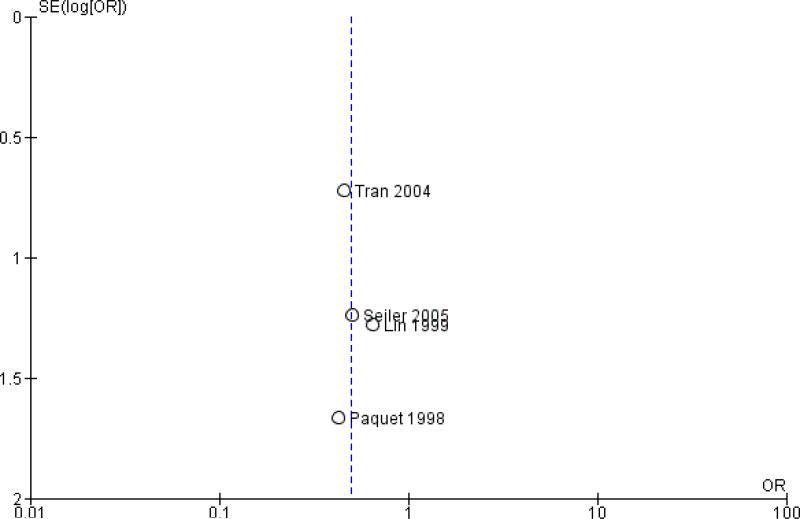

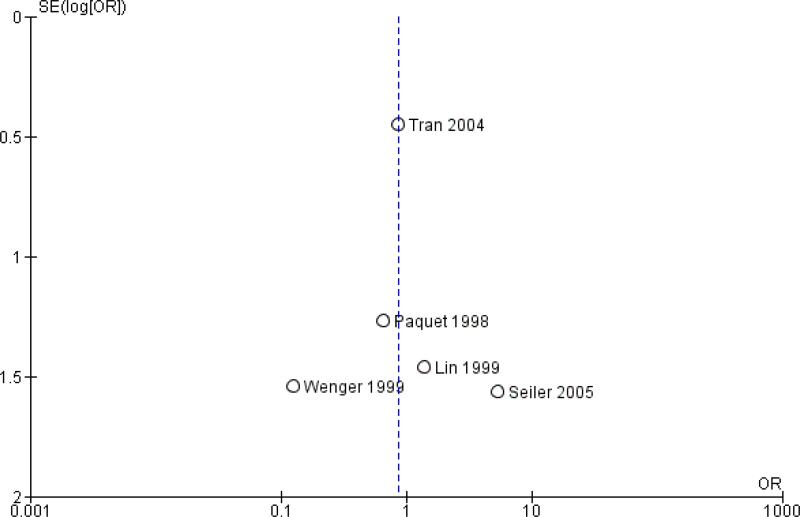

Publication bias was assessed by creating funnel plots for overall survival, mortality and pancreatic fistula, the last of which is the most common cause of postoperative morbidity. As fewer than 10 trials were included in all analyses (overall survival N = 3; mortality N = 5; pancreatic fistula N = 5), we inspected funnel plots for potential publication bias only. As a result, we did not observe asymmetry in any plot (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). Summary of findings tables for mortality, intraoperative blood loss and operating time, created on the basis of GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) criteria (GRADE 2008), showed low quality of evidence for all of these results (Summary of findings 2, Summary of findings 3 and Summary of findings 4).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Survival, outcome: 1.1 Overall.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Mortality, outcome: 2.1 Postoperative mortality.

Figure 6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 3 Pancreatic fistula, outcome: 3.1 Pancreatic fistula.

Allocation

No description of the sequence generation process was given in any of the trials. Tran et al (Tran 2004) described appropriate allocation concealment. Information about allocation concealment is missing for the other trials.

Blinding

None of the trials reported blinded outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data

We evaluated follow-up quality by assessing the follow-up sequence and the duration of follow-up. Median follow-up together with a range was reported in three trials (Bloechle 1999; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004) and varied from 18 months (Bloechle 1999) to 63.1 months (Seiler 2005). Two trials provided no information on follow-up (Lin 1999; Paquet 1998). Withdrawals or losses to follow-up were not reported in the trials.

Selective reporting

The trials by Seiler et al and Tran et al (Seiler 2005; Tran 2004) provided the most comprehensive definitions for analysed outcomes. Five trials did not specify adequately the criteria for the stated endpoints.

Effects of interventions

See: Summary of findings for the main comparison Survival after surgical treatment for periampullary or pancreatic carcinoma; Summary of findings 2 Mortality after surgical treatment for periampullary or pancreatic carcinoma; Summary of findings 3 Intraoperative blood loss in surgical treatment of patients with periampullary or pancreatic carcinoma; Summary of findings 4 Operating time in surgical treatment for periampullary or pancreatic carcinoma

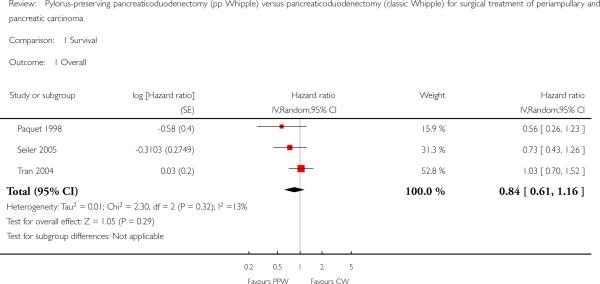

Survival

Four studies (Lin 1999; Paquet 1998; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004) provided survival data suitable for the meta-analysis: Long-term results (60 months (Paquet 1998; Lin 1999; Tran 2004) and 36 months (Seiler 2005) actuarial Kaplan-Meier analysis) from a total of 317 participants (152 PPW, 165 CW) were evaluated by comparing hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the random-effects model. We calculated HRs from survival rates at different time points as they were given in the Kaplan-Meier curves according to the method described by Parmar et al (Parmar 1998). Three trials presented Kaplan-Meier curves for periampullary and pancreatic head carcinoma together (Paquet 1998; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004). This analysis is based on the data provided for 284 participants (138 PPW, 146 CW). No significant differences could be observed in the pooled results (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.16; P value 0.29) (Analysis 1.1).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Survival, Outcome 1 Overall.

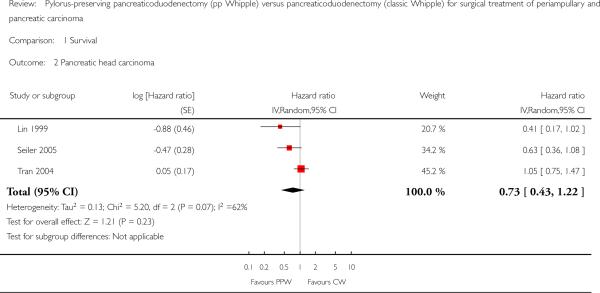

Three trials with 203 participants (98 PPW, 105 CW) presented Kaplan-Meier curves for those with pancreatic head carcinoma (Lin 1999; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004). Pooled results revealed no significant differences in survival (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.22; P value 0.23) (Analysis 1.2).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Survival, Outcome 2 Pancreatic head carcinoma.

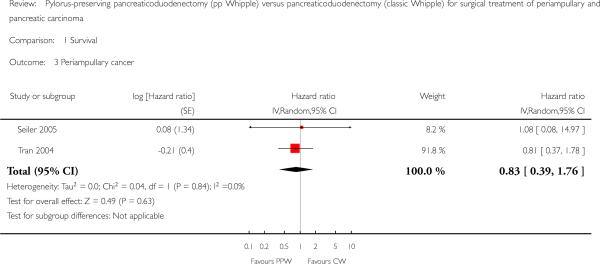

Two trials with 74 participants (37 PPW; 37 CW) presented Kaplan-Meier curves for periampullary carcinoma (Seiler 2005; Tran 2004), but the pooled HR showed no significant difference in survival for both groups (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.76; P value 0.63) (Analysis 1.3).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Survival, Outcome 3 Periampullary cancer.

Mortality

Mortality showed similar ranges in the PPW group (0% (Bloechle 1999) to 7.1% (Lin 1999)) and the CW group (0% (Bloechle 1999; Lin 1999) to 7% (Tran 2004)), respectively. The overall effect estimate of 205 (PPW) versus 212 (CW) participants revealed no significant differences in mortality (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.40; P value 0.18; I2 = 0% data heterogeneity) (Analysis 2.1).

Analysis 9.1.

Comparison 9 Postoperative bleeding, Outcome 1 Postoperative bleeding.

Parameters of morbidity

Data on pancreas-associated morbidity were inconclusive owing to broad ranges for rates of occurrence for pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying and biliary leakage. For more specific differentiation of the presumed underlying heterogeneity, we performed a meta-analysis of these parameters.

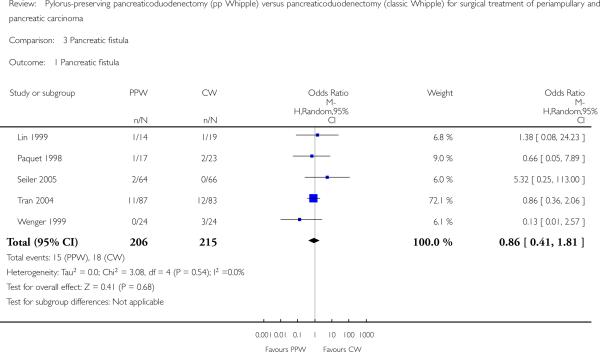

Pancreatic fistula

The fistula rate showed no differences between groups: 15 of 206 participants undergoing a PPW (7.2%) versus 18 of 215 participants in the CW group (8.4%) (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.81; P value 0.68; I2 = 0%). Tran et al defined a pancreatic fistula as drainage of more than 50 mL of amylase-rich fluid per day through surgically placed drains on or after postoperative day 10, or as pancreatic anastomotic disruption demonstrated radiographically (Tran 2004). Seiler et al defined it as secretion of 30 mL or more of amylase-rich drainage fluid (more than 5000 units/L) per day for at least 10 days (Seiler 2005). No definition was given in the other trials (Lin 1999; Paquet 1998; Wenger 1999) (Analysis 3.1). Although the I2 statistic showed no heterogeneity, the pooled results must be regarded with caution owing to the various definitions reported. Butturini et al showed that the incidence of pancreatic fistula varied from 10% to 28.5% within the same group of participants when different common definitions were applied (Butturini 2006).

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Pancreatic fistula, Outcome 1 Pancreatic fistula.

Delayed gastric emptying (DGE)

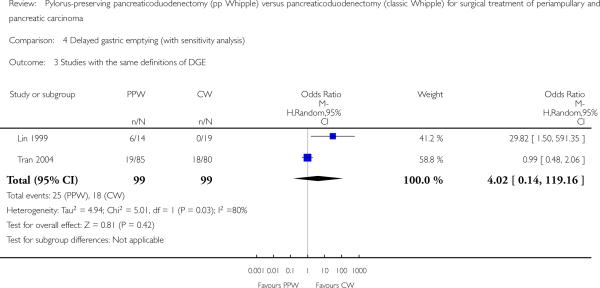

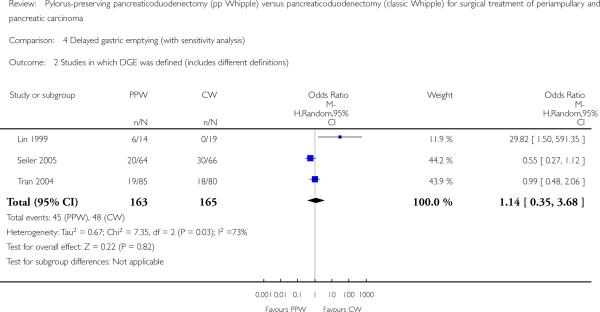

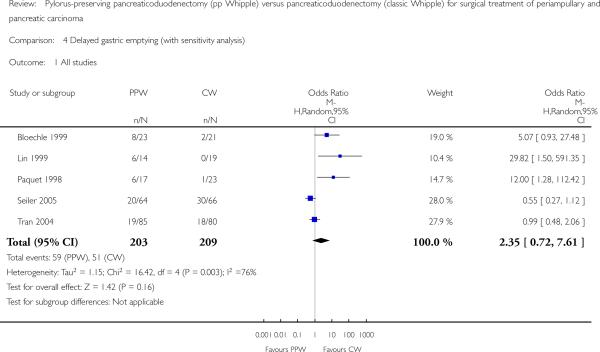

Five studies (Bloechle 1999; Lin 1999; Paquet 1998; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004) provided data from 412 participants (203 PPW, 209 CW) on the occurrence of DGE. Lin et al (2005) and Tran et al used the same definition for DGE (gastric stasis requiring naso-gastric intubation for 10 or more days), whereas Seiler et al defined it in a different way (persistent drainage via the nasogastric tube of more than 500 mL/d for at least five days after surgery, or recurrent vomiting in combination with oedema of the gastrojejunostomy or duodenojejunostomy and proximal dilatation on contrast radiography). No definition was given in the other trials. Owing to considerable statistical heterogeneity of 75.6% in the I2 statistic, we performed a sensitivity analysis that included studies only according to their definition of DGE, because it is well known that the rate of DGE varies with the underlying definition (Butturini 2006), but we could not explain the heterogeneity.

The conclusions were similar if only studies with the same definition of DGE were included (OR 4.02, 95% CI 0.14 to 119.16; P value 0.42; I2 = 80%) (Analysis 4.3), or if all studies that provided a definition for DGE were included (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.35 to 3.68; P value 0.82; I2 = 72.8%) (Analysis 4.2). In the first case, the data for 198 participants were analysed (PPW 99, CW 99), and in the second case, the data for 238 participants were analysed (163 PPW, 165 CW).

Analysis 4.3.

Comparison 4 Delayed gastric emptying (with sensitivity analysis), Outcome 3 Studies with the same definitions of DGE.

Analysis 4.2.

Comparison 4 Delayed gastric emptying (with sensitivity analysis), Outcome 2 Studies in which DGE was defined (includes different definitions).

Another factor that could account for the observed heterogeneity might be the different applications of drugs. Participants in the trials that showed no difference between treatment groups or that favoured PPW received octreotide (Seiler 2005; Tran 2004), whereas no participants in the trial by Lin et al were treated with octreotide. No statement about the application of drugs was provided for the two trials that favoured the CW group (Bloechle 1999; Paquet 1998). Owing to these restrictions, the following pooled results have to be regarded with care. Three studies (Bloechle 1999; Lin 1999; Paquet 1998) favoured CW, and one favoured PPW (Seiler 2005); one study (Tran 2004) reported equal rates for DGE. Pooling of these individual results revealed 59 participants of 203 (29.0%) with DGE in the PPW group compared with 51 of 209 (24.4%) in the CW group (OR 2.35, 95% CI 0.72 to 7.61; P value 0.16; I2 = 75.6%) (Analysis 4.1).

Analysis 4.1.

Comparison 4 Delayed gastric emptying (with sensitivity analysis), Outcome 1 All studies.

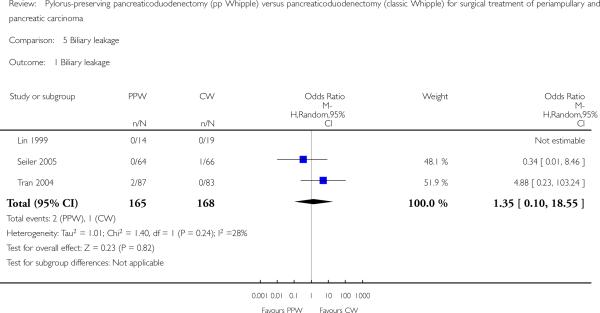

Biliary leakage

The summarised effect size of three RCTs (Lin 1999; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004) comparing biliary leakage after PPW and CW showed no differences: two of 165 (1.2%) in the PPW group versus one of 168 (0.5%) in the CW group (OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.10 to 18.55; P value 0.82; I2 = 28.3%) (Analysis 5.1).

Analysis 5.1.

Comparison 5 Biliary leakage, Outcome 1 Biliary leakage.

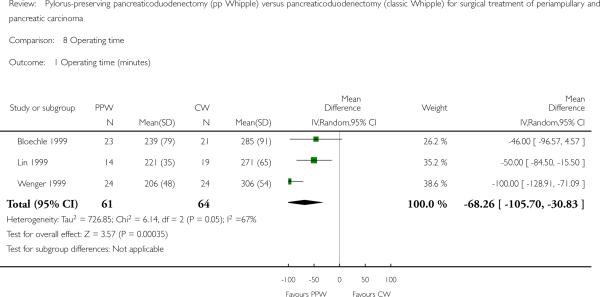

Perioperative parameters

A meta-analysis of perioperative parameters such as blood loss, red blood cell transfusion, operating time and duration of hospital stay for three RCTs (Bloechle 1999; Lin 1999; Wenger 1999) demonstrated a significant reduction in operating time (minutes) for the PPW operation (MD -68.26, 95% CI -105.7 to -30.83; P value 0.0004; I2 = 67.5% data heterogeneity). This analysis is based on data from 125 participants (61 PPW, 64 CW) (Analysis 8.1).

Analysis 8.1.

Comparison 8 Operating time, Outcome 1 Operating time (minutes).

The amount of intraoperative blood loss was analysed in 33 participants (14 PPW, 19 CW) in only one trial (Lin 1999). Blood loss was significantly reduced in the PPW group (MD -0.76, 95% CI -0.96 to -0.56; P value less than 0.00001) (Analysis 6.1).

Analysis 6.1.

Comparison 6 Intraoperative blood loss, Outcome 1 Intraoperative blood loss (litres).

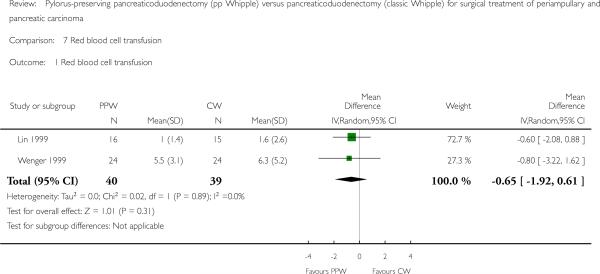

In contrast, the summarised effect estimate of blood replacement (units) indicates similar application of blood products intraoperatively (MD -0.65, 95% CI -1.92 to 0.61; P value 0.31; I2 = 0% data heterogeneity) (Analysis 7.1). This result is based on data from 79 participants in two studies (PPW 40, CW 39) (Lin 1999; Wenger 1999).

Analysis 7.1.

Comparison 7 Red blood cell transfusion, Outcome 1 Red blood cell transfusion.

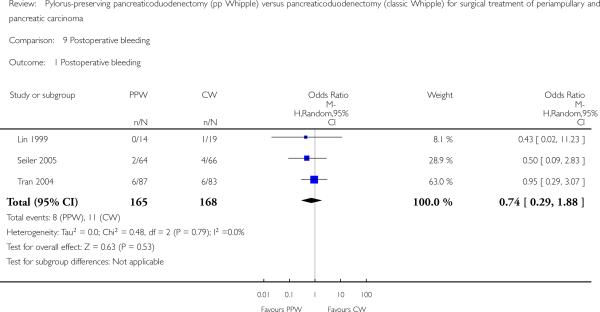

Postoperative bleeding

Three studies (Lin 1999; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004) evaluated postoperative bleeding. Eight of 165 participants (4.8%) in the PPW groups and 11 of 168 participants (6.5%) in the CW groups were identified; this finding was not statistically significant (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.88; P value 0.53; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 9.1).

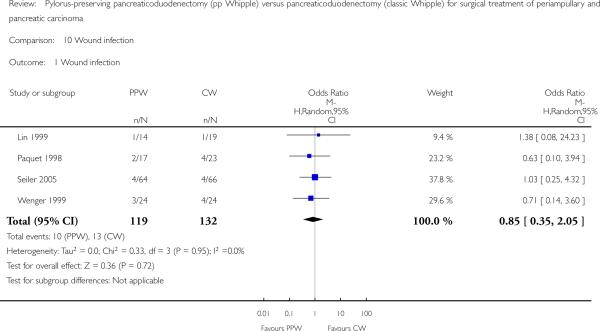

Wound infection

Wound infection yielded similar results and occurred in 10 of 119 participants in the PPW groups (8.4%) and in 13 of 132 participants in the CW groups (9.8%) (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.35 to 2.05; P value 0.72; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 10.1). Four trials reported incidences of wound infection but without definition (Lin 1999; Paquet 1998; Seiler 2005; Wenger 1999).

Analysis 10.1.

Comparison 10 Wound infection, Outcome 1 Wound infection.

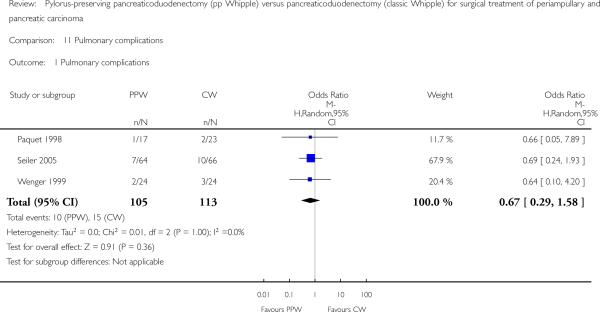

Pulmonary complications

Three trials reported pulmonary complications. Data for 218 participants were analysed (105 PPW, 113 CW). Wenger et al and Paquet et al (Paquet 1998; Wenger 1999) specified it as pneumonia, and Seiler et al referred to it as ’pulmonary morbidity’ (Seiler 2000). No significant differences between PPW and CW groups could be identified (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.58; P value 0.36) (Analysis 11.1).

Analysis 11.1.

Comparison 11 Pulmonary complications, Outcome 1 Pulmonary complications.

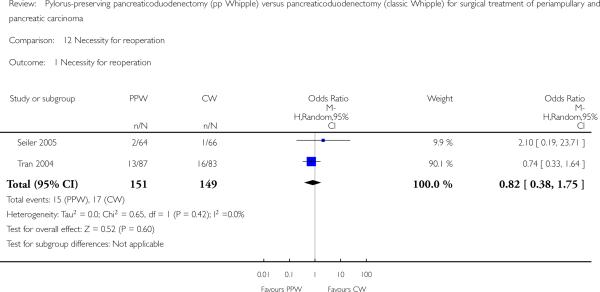

Necessity for reoperation

Seiler et al and Tran et al reported this outcome (Seiler 2005; Tran 2004). In total, 15 of 151 participants in the PPW groups (9.9%) and 17 of 149 participants in the CW groups (11.4%) required reoperation. This result did not show statistical significance (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.75; P value 0.6) (Analysis 12.1).

Analysis 12.1.

Comparison 12 Necessity for reoperation, Outcome 1 Necessity for reoperation.

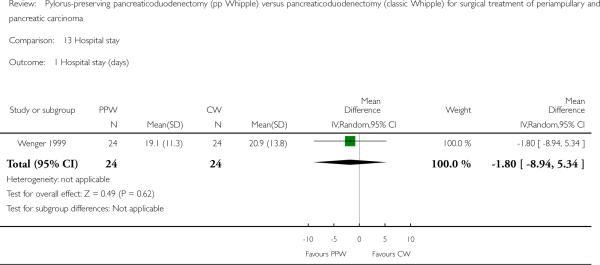

Duration of hospital stay

The duration of hospital stay (days) showed similar results in both groups (MD -1.80, 95% CI -8.94 to 5.34; P value 0.62), with only one article providing adequate data for pooling (Wenger 1999). Results of this analysis are based on data from 48 participants (24 PPW, 24 CW) (Analysis 13.1).

Analysis 13.1.

Comparison 13 Hospital stay, Outcome 1 Hospital stay (days).

Quality of life (QoL)

Owing to the use of different QoL questionnaires, it was impossible to pool these data quantitatively. Thus we present a qualitative overview of QoL results by operative procedure.

Three RCTs reported outcomes for QoL (Bloechle 1999; Seiler 2005; Wenger 1999). Bloechle et al and Wenger et al used the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)-QLQ-30 questionnaire in their RCTs, but only Wenger et al used the recommended pancreas-specific module QLQ-PAN 26 (Fitzsimmons 1998). The data from each RCT show no difference in QoL by procedure or a better QoL score after the PPW operation.

In the trial by Wenger et al, QoL was assessed preoperatively and after 2, 4, 6, 24, 36, 48 and 60 weeks. Participants in the PPW group scored significantly better on loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea and weight gain. No significant difference in overall QoL was noted.

Bloechle et al did not specify the assessment time points but, like Wenger, reported a significantly better score for participants in the PPW group on loss of appetite and weight gain but no difference in overall QoL, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting.

Seiler et al assessed QoL preoperatively using the Sickness Impact Profile and again after 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. This group found no differences in postoperative weight gain or overall QoL but did report that ability to work after six months was better for participants in the PPW group than for those in the CW group.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

Preservation of the pylorus in patients undergoing duodenopancreatectomy for cancer has been a controversial issue for the past decade. Numerous studies have been performed, including several randomised controlled trials (RCTs), but the cumulative knowledge gained from these needed to be captured in a quantitative summary of the results to establish whether or not pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPW) is a better technique than the classic Whipple (CW) operation.

From a curative perspective, no evidence of superiority of one procedure over the other could be found in this systematic review and meta-analysis. Pooled long-term results of four RCTs showed no differences in terms of overall survival (hazard ratio (HR) 0.84; P value 0.29).

Differences in mortality and morbidity between the two techniques are not statistically significant. As for surgical and clinically relevant parameters of morbidity, we found in particular no significant differences for the occurrence of pancreatic fistula (odds ratio (OR) 0.86; P value 0.68), biliary leakage (OR 1.35; P = 0.82) or postoperative bleeding (OR 0.74; P = 0.53). A trend suggests that PPW may reduce mortality, but these results were not statistically significant. Lack of statistical significance could be due to inclusion of insufficient numbers in randomised trials. Even if a difference in mortality rates between types of operations was reported, it would be unlikely that the difference would be huge. The significant reduction in operating time for the PPW (mean difference (MD) -68.26; P value 0.0004) is an advantage of the PPW in terms of cost, but the benefits of this reduced operation time for postoperative morbidity (e.g. pulmonary and cardiac complications) are unclear.

Results of the analysis of duration of hospital stay (Wenger 1999) should be interpreted with caution because the distribution of this outcome is known to be skewed, and because the sample size is small. It is also unclear whether the study authors included in their calculations participants who died during their hospital stay, as no data on mortality are presented in this article.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Our findings are in line with those of a recently published study from Bassi et al (Bassi 2005a), in which survival data were correlated with type of surgery by multi-variate analysis. These results indicated that neither the type of surgery (PPW vs CW: HR 0.8; P value 0.078) nor the occurrence of postoperative complications significantly affected the hazard of death once tumour staging was taken into account (grade, nodal status and maximum tumour size). As shown by Neoptolemos et al (Neoptolemos 2001), it was not resection margin status R0/R1 but rather tumour grade and lymph node status that were by far the most powerful prognostic factors of survival.

In terms of delayed gastric emptying (DGE), previous reports of non-randomised cohort studies (Mosca 1997; Roder 1992) stating higher rates after the PPW procedure could not be confirmed by the results of prior RCTs and our meta-analysis. Three of the seven included studies (Bloechle 1999; Lin 1999; Paquet 1998) showing higher rates of DGE in the PPW group were the smallest. Given a non-significant difference for the occurrence of DGE when all included studies are considered (29.0% PPW vs 24.4% CW; OR 2.35; P value 0.16), this result indicates that underpowered studies potentially overestimate the benefits of CW for the outcome of DGE.

If PPW and CW are equally effective regarding survival, mortality and morbidity, QoL could become the crucial factor in comparisons between the two procedures. Although three of the seven trials report QoL as an outcome, no conclusion can be reached because different questionnaires administered at different time points were used, and only sparse information about assessment of QoL is available in the study by Bloechle et al (Bloechle 1999).

Quality of the evidence

Given obvious sources of potential bias in the included trials, such as small sample sizes, varying or missing definitions of outcome parameters and inexplicit methods of randomisation and allocation concealment, our results should be interpreted with caution. We observed no clear differences between PPW and CW techniques. However, to demonstrate potential superiority of one or the other technique, much larger and rigorously designed studies than are currently available would be needed. This highlights the urgent need for the development of standardised RCTs for complex interventions. Moreover, these trials should rely on evidence-based consensus definitions of surgical interventions and their outcome parameters.

Potential biases in the review process

Systematic reviews currently provide the best method of summarising existing evidence, but the quality of such reviews depends on the quality of the primary studies (Egger 1997b; Mulrow 1994). Thus, the reviewed studies are partially marred by bias and clinical heterogeneity, and this may distort results.

Our Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy was approved by an expert in the field (GA), but it may still be biased. In an attempt to identify all relevant studies, we contacted experts in pancreatic surgery and in clinical research to identify ongoing trials. However, these efforts revealed no additional studies.

The fact that the randomisation process was carried out differently in the reviewed studies can be considered as a source of bias, because adequate randomisation and allocation concealment generate balanced groups for known, unknown and unmeasured confounders. Three of the seven included studies (Paquet 1998; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004) provided adequate descriptions of the randomisation process, whereas the other four studies failed to describe the method of allocation satisfactorily.

Moreover, maintenance of allocation concealment and blinding of the outcome assessor were specified in only two trials (Seiler 2005; Tran 2004).

In addition, median follow-up and follow-up sequences varied significantly between individual studies (median follow-up 18 months (Bloechle 1999) to 144 months (Paquet 1998)). This insufficient reporting on inconsistent follow-up sequences is a possible indicator of performance bias.

Furthermore, we found varying or even missing definitions of surrogate parameters such as pancreatic fistula and DGE. The trials by Seiler et al and Tran et al provided the most comprehensive definitions (Seiler 2005; Tran 2004). The other trials did not specify the criteria of their endpoints at all. The heterogeneous definition of outcome parameters may have caused detection bias.

Internationally accepted scaled definitions for surgical outcome parameters in pancreatic cancer surgery are lacking. Efforts such as the consensus conference of the International Study Group for Definition of Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula or Definition of Post-Pancreatectomy Haemorrhage should be encouraged, to decrease interobserver variability (Bassi 2005b; Wente 2007).

Regarding the use of antibiotics, somatostatin, drains, nasogastric tubes, etc., we observed a non-standardised therapeutic concept or even non-reporting with respect to dosage, route, frequency and duration of administration. Thus, the considerable variation in perioperative management is a further indicator of interstudy heterogeneity, and this may influence the external validity of the summarised results.

Another possible source of bias lies in the statistical analysis. Only one trial (Tran 2004) used an intention-to-treat approach, whereas the six remaining trials applied per-protocol analysis. This distorted analysis of participants lost to follow-up or missing information on excluded participants (attrition bias) makes it difficult to decide whether the remaining study population is representative (external validity). Moreover, statistical analysis of obviously underpowered trials (four trials (Bloechle 1999; Lin 1999; Paquet 1998; Wenger 1999) represent only 40% of the total number of participants) reduces the explanatory power of these results. A power calculation was reported for only two trials (Seiler 2005; Tran 2004), and some of the results may not reach statistical significance owing to the lack of an appropriate number of participants.

In this context, we should point out that we did not investigate the influence of neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment because relevant data were not reported in an interpretable way in the reviewed studies. Our results may therefore be biased, because adjuvant treatment (e.g. chemotherapy, chemoradiation) represents a possible confounder with an impact on survival, mortality and morbidity.

In spite of the sources of clinical and methodological heterogeneity already mentioned, we still observed adequately balanced groups when we compared interstudy baseline population characteristics: All analysed participants were included because of suspected pancreatic or periampullary carcinoma. Our systematic review also revealed a balanced distribution of R0/R1 resections (mean R0 resection: 91.1% (PPW), 90.4% (CW)) and lymph node status (mean positive lymph node status: 54.4% (PPW), 60.3% (CW)). The calculated average level of statistical heterogeneity of all 15 meta-analytical approaches indicated moderate heterogeneity of 11.3% (I2 statistic). Nevertheless, given obvious sources of clinical and methodological heterogeneity, we decided to compute the statistics of our meta-analysis using the random-effects model, which allows for variation in the treatment effects of individual studies, while providing a more conservative pooled effect estimate (DerSimonian 1986).

Given the obvious sources of bias, the results of our systematic review and meta-analyses have to be interpreted with caution. Small sample size, missing definitions of outcome parameters and inexplicit randomisation and allocation concealment are some of the most relevant factors that can produce misleading results. Seven trials providing high-level evidence addressing identical surgical problems produced many examples of clinically relevant heterogeneity. This calls for future efforts to overcome current hurdles to achieving standardised RCTs for complex interventions. Moreover, evidence-based consensus is mandatory to establish refined definitions for surgical interventions and their putative outcome parameters. This systematic review and meta-analysis of the PPW versus the CW procedure could serve as an ideal basis for the pursuit of such endeavours.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This study agrees with the conclusions of the authors of all included trials (Bloechle 1999; Lin 1999; Paquet 1998; Seiler 2005; Tran 2004; Wenger 1999). It also agrees with the findings of a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials on this topic (Other published versions of this review).

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

To conclude, we must recognise that no evidence suggests a difference between the pylorus-preserving procedure and the CW operation in terms of survival, mortality and morbidity, as far as can be assessed on the basis of currently existing randomised trials. It does appear, however, that the pylorus-preserving procedure may reduce operating time and blood loss.

Implications for research

To demonstrate superiority of one of these procedures over the other, much larger and more rigorously designed studies than those currently available are needed. The ideal future study would be a non-inferiority (thousands of participants) multi-centre RCT, which hardly seems feasible owing to the present lack of funding in this field. Another option would be an additional meta-analysis including RCTs and observational studies for outcomes that are less susceptible to bias (e.g. mortality, survival) than those depending on individual definitions.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included Studies [ordered by study ID]

| Bloechle 1999 | |

|---|---|

| Methods | Method of randomisation:

unknown Number randomly assigned: 44 (PPW = 23, CW = 21) Exclusion after randomisation (total and per group): none Losses to follow-up: yes Method of allocation concealment: unknown Intention-to-treat analysis: no Description of sample size calculation: none |

| Participants | Age, years: 69 (47 to 76) (median

and range in the PPW group); 67 (43 to 78) (median and range

in the CW group) Sex ratio (m/f): 1.6 (PPW), 1.5 (CW) Inclusion criteria: patients with periampullary carcinoma (cTl-4, cN0-1, cM0) Exclusion criteria: none Equivalence of baseline characteristics: age and stage distribution similar for both groups |

| Interventions | PPW and CW (no operation details

available) Erythromycin application unknown Somatostatin application unknown |

| Outcomes | Description of outcome parameters:

insufficient Operation time (minutes): PPW: 239 ± 79; CW: 285 ± 91 Mortality: PPW: 0%; CW: 0% DGE: PPW: 8 (34%); CW: 2 (9%) |

| Notes | Country: Germany Time of enrolment: unknown Duration of follow-up: median 18 months (range 12 to 30) The trial investigator did not define the term 'periampullary cancer'; it is assumed that it includes patients with pancreatic head cancer |

| Risk of bias | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and

detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of participants and

personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment

(detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition

bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Comment: Postrandomisation dropouts could have influenced effect estimates |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no study protocol available |

| Other bias | High risk | Comment: sample size calculation not reported |

| Lin 1999 | |

|---|---|

| Methods | Method of randomisation:

unknown Number randomly assigned: 33 (PPW = 14, CW = 19) Exclusion after randomisation (total and per group): 3 (PPW = 3, CW = 0) Losses to follow-up: yes Method of allocation concealment: unknown Intention-to-treat analysis: no Description of sample size calculation: none |

| Participants | Age, years: 64.5 (48 to 77) (mean

and range in the PPW group); 66.7 (46 to 84) (mean and range

in the CW group) Sex: ratio (m/f): 2.5 (PPW), 2.2 (CW) Inclusion criteria: patients with pancreatic head carcinoma Exclusion criteria: none Equivalence of baseline characteristics: Participants were equivalent in terms of age and sex distribution; the CW group included more participants with stage III cancer |

| Interventions | PPW and CW (no operation details

available) No somatostatin used Erythromycin application unknown |

| Outcomes | Operation time (minutes): PPW: 221

± 35; CW: 271 ± 65 Blood loss (mL): PPW: 446 ± 342; CW: 1212 ± 194 Blood replacement (units): PPW: 1.0 ± 1.4; CW: 1.6 ± 2.6 Mortality: PPW: 1 (7.1%); CW: 0 (0%) DGE: PPW: 6 (42.8%); CW: 0 (0%) Bleeding: PPW: 0 (0%); CW: 1 (5.2%) Fistula: PPW: 1 (7.1%); CW: 1 (5.2%) Bile leak: PPW: 0 (0%); CW: 0 (0%) Wound infection: PPW: 1 (7.1%); CW: 1 (5.2%) Intra-abdominal abscess: PPW: 0 (0%); CW: 1 (5.2%) |

| Notes | Country: Taiwan Time of enrolment: 156 weeks Duration of follow-up: unknown All operations performed by the same surgeon |

| Risk of bias | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and

detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of participants and

personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment

(detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition

bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Comment: Postrandomisation dropouts could have influenced effect estimates |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no study protocol available |

| Other bias | High risk | Comment: sample size calculation not reported |

| Paquet 1998 | |

|---|---|

| Methods | Method of randomisation: sealed

envelopes (information from study author) Number randomly assigned: 40 (PPW = 17, CW = 23) Exclusion after randomisation (total and per group): unknown Losses to follow-up: unknown Method of allocation concealment: unknown Intention-to-treat analysis: no Description of sample size calculation: none |

| Participants | Age, years: unknown Sex: unknown Inclusion criteria: patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma or periampullary cancer and an R0 resection Exclusion criteria: none Equivalence of baseline characteristics: unknown |

| Interventions | Anastomoses: retrocolic end-to-end

pancreaticojejunostomy with a drain in the pancreatic duct,

end-to-end hepaticojejunostomy, end-to-end

duodenojejunostomy Erythromycin application unknown Somatostatin application unknown |

| Outcomes | Description of outcome parameters:

insufficient Mortality: PPW: 0 (0%); CW: 1 (4%) DGE: PPW: 6 (35%); CW: 1 (4%) Fistula: PPW: 1 (6%); CW: 2 (9%) Radicality (R0): PPW: 17 (100%); CW: 23 (100%) (condition for inclusion) |

| Notes | Country: Germany Time of enrolment: 521 weeks Duration of follow-up: minimum = 24 months, maximum = 144 months |

| Risk of bias | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: “Sealed envelopes” were used (information obtained from the study author upon request) |

| Blinding (performance bias and

detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of participants and

personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment

(detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition

bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Comment: no postrandomisation dropouts reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no study protocol available |

| Other bias | High risk | Comment: sample size calculation not reported |

| Seiler 2005 | |

|---|---|

| Methods | Method of randomisation: sealed

envelopes Number randomly assigned: 130 (PPW = 64, CW = 66) Exclusion after randomisation (total): 84 (group distribution unknown) Losses to follow-up: unknown Method of allocation concealment: unknown Intention-to-treat analysis: no Description of sample size calculation: yes |

| Participants | Age, years: 64.8 (26 to 83)

(median and range in the PPW group); 65 (33 to 86) (median

and range in the CW group) Sex: ratio (m/f): 1.29 (PPW), 1 (CW) Inclusion criteria: all patients suitable for surgery, with suspected pancreatic or peri-ampullary cancer considered resectable on the basis of computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, with no history of previous gastric resection Exclusion criteria: direct tumour invasion ofthe proximal duodenum, pylorus or stomach; peripyloric lymph node metastases confirmed by intraoperative frozen-section examination; distant metastases or locally unresectable tumours due to major retroperitoneal infiltration; emergency resections; necessity for total pancreatectomy to achieve clear resection margins Equivalence of baseline characteristics: Groups were similar regarding age, sex and stage distribution |

| Interventions | Reconstruction performed by means

of an interrupted 2-layer end-to-side pancreatojejunostomy,

an end-to side hepaticojejunostomy 10 to 15 cm distal to the

pancreatic anastomosis and an end-to-side

gastrojejunostomy/duodenojejunostomy approximately 40 cm

distal to the biliodigestive anastomosis, followed by a

Braun jejunojejunostomy Somatostatin application: 100-200 μg 3 × 1 (7 days) Erythromycin application: none Perioperative treatment: antibiotic prophylaxis |

| Outcomes | Operation time (minutes): PPW: 382

(240 to 645); CW: 449 (240 to 780) Blood loss (mL): PPW: 1198 (400 to 4000); CW: 1500 (400 to 6000) Blood replacement (units): PPW: 0.9 (0 to 6); CW: 1.9 (0 to 10) Hospital stay (days): PPW: 19.7 (10 to 61); CW: 20.8 (8 to 67) Mortality: PPW: 1 (2%); CW: 2 (3%) DGE: PPW: 20 (31%); CW: 30 (45%) Bleeding: PPW: 2 (3%); CW: 4 (6%) Fistula: PPW: 2 (3%); CW: 1 (2%) Bile leak: PPW: 0 (0%); CW: 1 (1.5%) Infection (wound or abscess): PPW: 4 (6%); CW: 4 (6%) Positive LNs: PPW: 33 (62%); 41 (72%) Radicality (R0): PPW: 48 (91%); 45 (79%) |

| Notes | Country: Germany Time of enrolment: 274 weeks Duration of follow-up: median = 63.1 months, minimum = 4 months, maximum = 93 months |

| Risk of bias | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: envelopes used for randomisation but unclear whether envelopes were opaque |

| Blinding (performance bias and

detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of participants and

personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment

(detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition

bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Comment: no postrandomisation dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | - |

| Tran 2004 | |

|---|---|

| Methods | Method of randomisation: sealed

envelopes Number randomly assigned: 170 (PPW = 87, CW = 83) Exclusion after randomisation (total and per group): 36 (PPW = 17, CW = 19) Losses to follow-up: unknown Method of allocation concealment: unknown Intention-to-treat analysis: yes Description of sample size calculation: yes |

| Participants | Age, years: 64 (43 to 78) (median

and range in the PPW group); 62 (27 to 78) (median and range

in the CW group) Sex: ratio (m/f): 2.32 (PPW), 1.35 (CW) Inclusion criteria: inclusion of consecutive patients with suspected pancreatic or periampullary cancer that was assumed to be resectable according to preoperative diagnostic imaging Exclusion criteria: previous gastric resection, distant metastasis or local unresectable tumours, direct invasion of the pylorus or stomach, positive peripyloric lymph nodes Equivalence of baseline characteristics: groups similar regarding age, sex and stage distribution |

| Interventions | End-to-side invaginated

pancreaticojejunostomy, end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy,

side-to-side gastroenterostomy or end-to-side

pylorus-jejunostomy Somatostatin application: 100 μg preoperatively + 3 × 1 postoperatively (7 days) Erythromycin application: none Perioperative treatment: antibiotic prophylaxis, H2-receptor antagonists, drain in operation area |

| Outcomes | Operation time (minutes): PPW: 300

(130 to 600); CW: 300 (160 to 480) Blood loss (mL): PPW: 2000 (400 to 21,000); CW: 2000 (300 to 9500) Blood replacement (units): PPW: 2; CW: 2 Hospital stay (days): PPW: 18 (4 to 175); CW: 20 (11 to 138) Mortality: PPW: 3 (3%); CW: 6 (7%) DGE: PPW: 19/85 (22%); CW: 18/80 (23%) Bleeding: PPW: 6 (7%); CW: 6 (7%) Fistula: PPW: 11 (13%); CW: 12 (14%) Bile leak: PPW: 2 (2%); CW: 0 (0%) Intra-abdominal abscess: PPW: 9 (10%); CW: 8 (10%) Re-laparotomy: PPW: 13 (15%); CW: 16 (19%) Positive LNs: PPW: 37/72 (51.4%); 38/69 (55%) Radicality (R0): 53/72 (73.6%); 57/69 (82.6%) |

| Notes | Country: Germany Time of enrolment: 465 weeks Duration of follow-up: median = 18.5 months, minimum = 1 month, maximum = 115 months |

| Risk of bias | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “An equal number of blind envelopes with protocols for the SW and the PPPD resection was prepared. The envelopes were used sequentially as patients were enrolled in the study. Therefore, there was strict randomization in both arms. Randomization was carried out in the operation room: a sealed envelope was opened only after it was ascertained that both operation techniques were feasible in the patient concerned” |

| Blinding (performance bias and

detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of participants and

personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment

(detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition

bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Comment: Reasons for exclusion from long-term survival analysis are given (e.g. non-malignant disease) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

| Wenger 1999 | |

|---|---|

| Methods | Method of randomisation:

unknown Number randomly assigned: 48 (PPW = 24, CW = 24) Exclusion after randomisation (total and per group): none Method of allocation concealment: unknown Intention-to-treat analysis: no Description of sample size calculation: none |

| Participants | Age, years: 61.2 ± 7.2

(mean and SD in the PPW group); 61.6 ± 8.9 (mean and

SD in the CW group) Sex: ratio (m/f): 1 (PPW), 1 (CW) Inclusion criteria: all patients with a preoperative diagnosis of a ductal carcinoma of the pancreatic head or a periampullary carcinoma, an R0 resection and postoperative affirmation of the diagnosis Exclusion criteria: tumour infiltration of the stomach, the superior part of the duodenum or the pylorus; age > 75; peritoneal carcinosis; reduced general condition; heart insufficiency; renal insufficiency; hepatic insufficiency; pulmonary insufficiency Equivalence of baseline characteristics: groups similar regarding age, sex and stage distribution |

| Interventions | PPW and CW (no description of

procedures) Somatostatin application: unknown Erythromycin application: unknown |

| Outcomes | Operation time (minutes): PPW: 206

± 48; CW: 306 ± 54 Blood replacement (units): PPW: 5.5 ± 3.1; CW: 6.3 ± 5.2 Hospital stay (days): PPW: 19.1 ± 11.3; CW: 20.9 ± 13.8 Wound infection: PPW: 3 (12.5%); CW: 4 (16.6%) Positive LNs: PPW: 12 (50%); 13 (54%) Radicality (R0): PPW: 24 (100%); 24 (100%) |

| Notes | Country: Germany Time period for enrolment: 208 weeks Follow-up: assessed at 2, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 weeks; median and range not available |

| Risk of bias | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and

detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding of participants and

personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Blinding ofoutcome assessment

(detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition

bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Comment: no postrandomisation dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not reported |

| Other bias | High risk | Comment: sample size calculation not reported |

CW: Classic Whipple.

DGE: Delayed gastric emptying.

LNs: Lymph nodes.

μg: Micrograms.

mL: Millilitres.

PPW: Pylorus-preserving Whipple.

SD: Standard deviation.

Characteristics of excluded Studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bakkevold 1993 | Non-randomised study design; no comparison of PPW versus CW |

| Bassi 1994 | No comparison of PPW versus CW |

| Bell 2005 | Narrative review of 1 included RCT |

| Brennan 1994 | No comparison of PPW versus CW |

| Buchler 1993 | No comparison of PPW versus CW |

| Chou 1996 | No comparison of PPW versus CW |

| Farnell 2005 | No comparison of PPW versus CW |

| Friess 1996 | No comparison of PPW versus CW |

| Johnstone 1993 | No comparison of PPW versus CW |

| Nguyen 2003 | No comparison of PPW versus CW |

| Pedrazzoli 1998 | No comparison of PPW versus CW |

| Seiler 2000 | Additional publication on the same trial (Seiler 2005). No additional information |

| Shan 2003 | No comparison of PPW versus CW |

| van Berge Henegouwen | Non-randomised study design; insufficient quantitative outcome parameters |

| Wagner 2004 | Non-randomised study design |

| Yeo 1999 | Study randomised not for the comparison ofPPW versus CW |

CW: Classic Whipple.

PPW: Pylorus-preserving Whipple.

RCT: Randomised controlled trial.

DATA AND ANALYSES

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Comparison of the stomach-preserving ‘Whipple’ operation with the classic ‘Whipple’ operation for patients with cancer of the pancreas or the periampullary region (the point at which the ducts from the liver and pancreas enter the small intestine)

Pancreatic cancer is a leading cause of cancer death. Two surgical procedures can lead to a cure: the classic Whipple operation, in which part of the pancreas, the gallbladder, the duodenum, the pylorus (outlet of the stomach) and the distal (lower) part of the stomach are removed, and the so-called pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, or pylorus-preserving Whipple operation, in which the stomach and the pylorus are not removed.

It is unclear whether the pylorus-preserving Whipple results in a higher rate of recurrence of the tumour because it is less extensive and so may be less radical, but it is also unknown whether quality of life is decreased after removal of the lower portion of the stomach. Another uncertainty is whether the two methods are associated with different rates or types of complications.

We included in this review six randomised controlled trials with a total of 496 participants. We could identify no differences in terms of complications, long-term survival or death due to complications after the operation, but operating time and blood loss seem to be less in the group treated with the pylorus-preserving Whipple operation. Our conclusion is that, at present, no difference is evident between the two surgical procedures for the treatment of pancreatic or periampullary cancer.

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Mortality, Outcome 1 Postoperative mortality.

Comparison 1.

Survival

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall | 3 | Hazard ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.61, 1.16] | |

| 2 Pancreatic head carcinoma | 3 | Hazard ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.43, 1.22] | |

| 3 Periampullary cancer | 2 | Hazard ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.39, 1.76] |

Comparison 2.

Mortality

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postoperative mortality | 5 | 417 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.17, 1.40] |

Comparison 3.

Pancreatic fistula

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pancreatic fistula | 5 | 421 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.41, 1.81] |

Comparison 4.

Delayed gastric emptying (with sensitivity analysis)

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All studies | 5 | 412 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.35 [0.72, 7.61] |

| 2 Studies in which DGE was defined (includes different definitions) | 3 | 328 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.35, 3.68] |

| 3 Studies with the same definitions of DGE | 2 | 198 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 4.02 [0.14, 119.16] |

Comparison 5.

Biliary leakage

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Biliary leakage | 3 | 333 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.10, 18.55] |

Comparison 6.

Intraoperative blood loss

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Intraoperative blood loss (litres) | 1 | 33 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −0.76 [−0.96, −0.56] |

Comparison 7.

Red blood cell transfusion

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Red blood cell transfusion | 2 | 79 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −0.65 [−1.92, 0.61] |

Comparison 8.

Intraoperative blood loss

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Operative time (minutes) | 3 | 125 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −68.26 [−105.70, −30.83] |

Comparison 9.

Postoperative bleeding

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postoperative bleeding | 3 | 333 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.29, 1.88] |

Comparison 10.

Wound infection

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Wound infection | 4 | 251 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.35, 2.05] |

Comparison 11.

Pulmonary complications

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pulmonary complications | 3 | 218 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.29, 1.58] |

Comparison 12.

Necessity for reoperation

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Necessity for reoperation | 2 | 300 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.38, 1.75] |

Comparison 13.

Hospital stay

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hospital stay (days) | 1 | 48 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −1.80 [−8.94, 5.34] |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This review was carried out on the basis of a systematic review and meta-analysis published elsewhere (Diener 2007).

Christina Fitzmaurice holds a T32 NIH training grant (United States of America).

APPENDICES

Appendix 1. Search strategy

-

(1)

exp Pancreatic Neoplasms/

-

(2)

(pancrea$ adj5 neoplas$).tw.

-

(3)

(pancrea$ adj5 cancer$).tw.

-

(4)

(pancrea$ adj5 carcin$).tw.

-

(5)

(pancrea$ adj5 tumo$).tw.

-

(6)

(pancrea$ adj5 malig$).tw.

-

(7)

or/2-6

-

(8)

exp pancreatectomy/

-

(9)

pancreatectom$.tw.

-

(10)

exp pancreaticoduodenectomy/

-

(11)

pancreaticoduodenectom$.tw.

-

(12)

pancreatoduodenectom$.tw.

-

(13)

duodenopancreatectom$.tw.

-

(14)

exp pancreaticojejunostomy/

-

(15)

pancreaticojejunostom$.tw.

-

(16)

pancreatojejunostom$.tw.

-

(17)

pancrea$ resect$.tw.

-

(18)

whipple.tw.

-

(19)

(pylorus adj3 preserv$).tw.

-

(20)

or/8-19

-

(21)

7 and 20

Appendix 2. Data extraction details

We extracted the following data.

Title, authors, contact address.

Source.

Published/unpublished.

Year of publication.

Trial sponsors.

Method of randomisation.

Blinding for outcome assessor, participant and carer.

Criteria for patient inclusion and exclusion.

Sample size and sample size calculation.

Baseline characteristics and similarities of groups at baseline.

Withdrawals and losses to follow-up.

Participant characteristics including mean/median age, age range, sex ratio.

Specific pancreatic diagnosis leading to surgical intervention.

Number of participants assigned to each treatment group.

Details of intervention regimens.

Survival related to each intervention (hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), log-rank Chi2 values, log-rank P values).

Postoperative mortality related to each intervention.

Number of lymph nodes removed in each group.

Status of resection margins.

Blood loss related to each intervention.

Operation time related to each intervention.

Duration of hospital stay related to each intervention.

Definition of postoperative complications.

Number and frequency of postoperative complications related to each intervention.

Definitions of adverse reactions and outcomes.

Adverse reactions and outcomes.

Quality of life.

WHAT'S NEW

Last assessed as up-to-date: 10 July 2014.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 November 2014 | Amended | Details of NIH funding held by review author included in acknowledgements |

HISTORY

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2006

| Review first published: Issue 2, 2008 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Date | Event | Description |

| 21 May 2014 | New search has been performed | Study flow diagram added as a figure. Some minor errors revised |

| 21 May 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No new trials identified. |

| 13 April 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No new trials identified. |

| 22 February 2011 | New search has been performed | No new trials identified. |

| 4 January 2011 | Amended | Withdrawn while results of updated literature search were incorporated |

| 5 October 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 12 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to RevMan 5 format. ‘Risk of bias’ table added. |

| 29 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTIONS OF AUTHORS

Markus Diener and Christina Fitzmaurice contributed equally to this work.

MKD

Designing the review.

Collecting data for the review.

Undertaking searches.

Screening search results.

Organising retrieval of papers.

Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria.

Appraising quality of papers.

Extracting data from papers.

Writing to authors of papers to ask for additional information.

Providing additional data about papers.

Obtaining and screening data on unpublished studies.

Managing data for the review.

Entering data into RevMan.

Analysing data.

Interpreting data.

Providing a methodological perspective.

Providing a clinical perspective.

Providing a consumer perspective.

Writing the review.

Performing previous work that served as the foundation of the current study.

CF

Collecting data for the review.

Designing search strategies.

Undertaking searches.

Screening search results.

Organising retrieval of papers.

Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria.

Appraising quality of papers.

Extracting data from papers.

Writing to authors of papers to ask for additional information.

Providing additional data about papers.

Obtaining and screening data on unpublished studies.

Managing data for the review.

Entering data into RevMan.

Analysing data.

Interpreting data.

Writing the review.

Revising the review after peer review.

GS

Extracting data from papers.

Analysing data.

Interpreting data.

CMS

Providing a methodological perspective.

Providing general advice on the review.

Interpreting the data.

Providing a clinical perspective.

Providing a policy perspective.

FH

Screening search results.

Organising retrieval of papers.

Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria.

Providing a clinical perspective.

Updating the review.

GA

Providing a methodological perspective.

Providing general advice on the review.

MWB

Providing a clinical perspective.

Providing a policy perspective.

Providing general advice on the review.

HPK

Conceiving of the review.

Co-ordinating the review.

Interpreting the data.

Providing general advice on the review.

Providing a clinical perspective.

Providing a policy perspective.

Citation: Diener MK, Fitzmaurice C, Schwarzer G, Seiler CM, Hüttner FJ, Antes G, Knaebel HP, Büchler MW. Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (pp Whipple) versus pancreaticoduodenectomy (classic Whipple) for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD006053. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006053.pub5.

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST

None known.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PROTOCOL AND REVIEW

- We summarised the outcomes of postoperative bleeding and postoperative gastrointestinal bleeding into a single outcome.

- We discarded the outcomes of intra-abdominal fluid collection/abscess, duration of intensive care unit stay, early and late dumping, postoperative reflux, number and status of removed lymph nodes, shock, sepsis, renal failure, weight loss and endocrine and exocrine insufficiency because no usable data were available.

- We performed an additional quality assessment on the basis of a checklist developed by Downs et al (Downs 1998).

- We performed a subgroup analysis for pancreatic head cancer and periampullary cancer for survival.

- We performed a sensitivity analysis for DGE by using different definitions.

Christina Fitzmaurice and Markus Diener are joint first review authors and have contributed equally to this work.

INDEX TERMS

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Ampulla of Vater [*surgery]; Common Bile Duct Neoplasms [mortality; *surgery]; Gastric Emptying; Pancreatic Fistula [etiology]; Pancreatic Neoplasms [mortality; *surgery]; Pancreaticoduodenectomy [adverse effects; *methods; mortality]; Pylorus [*surgery]; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words

Humans

REFERENCES

- Bloechle C, Broering DC, Latuske C. Prospective randomized study to evaluate quality of life after partial pancreatoduodenectomy according to Whipple versus pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy according to Longmire-Traverso for periampullary carcinoma. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chirurgie. 1999;(Supplement 1):661–4. Forumband. [Google Scholar]

- Lin PW, Lin YJ. Prospective randomized comparison between pylorus-preserving and standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. British Journal of Surgery. 1999;86(5):603–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PW, Shan YS, Lin YJ, Hung CJ. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic head cancer: PPPD versus Whipple procedure. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52(65):1601–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquet K-J. Comparison of Whipple's pancreaticoduodenectomy with the pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy-a prospectively controlled, randomized long-term trial [Vergleich der partiellen Duodenopankreatektomie (Whipple–Operation) mit der pyloruserhaltenden Zephaloduodenopankreatektomie-eine prospektive kontrollierte, randomisierte Langzeitstudie]. Chirurgische Gastroenterologie. 1998;14:54–8. [Google Scholar]

- Seiler CA, Wagner M, Bachmann T, Redaelli CA, Schmied B, Uhl W, et al. Randomized clinical trial of pylorus-preserving duodenopancreatectomy versus classical Whipple resection-long term results. British Journal of Surgery. 2005;92(5):547–56. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran KT, Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Kazemier G, Hop WC, Greve JW, et al. Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy versus standard Whipple procedure: a prospective, randomized, multicenter analysis of 170 patients with pancreatic and periampullary tumors. Annals of Surgery. 2004;240(5):738–45. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143248.71964.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger FA, Jacobi CA, Haubold K, Zieren HU, Muller JM. Gastrointestinal quality of life after duodenopancreatectomy in pancreatic carcinoma. Preliminary results of a prospective randomized study: pancreatoduodenectomy or pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Chirurg. 1999;70:1454–9. doi: 10.1007/pl00002580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]