Abstract

Purpose.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the protective mechanisms evoked by TLR2 and MyD88 signaling in bacterial endophthalmitis in vivo.

Methods.

Endophthalmitis was induced in wild-type (WT), TLR2−/−, MyD88−/−, and Cnlp−/− mice by intravitreal injections of a laboratory strain (RN6390) and two endophthalmitis isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Disease progression was monitored by assessing corneal and vitreous haze, bacterial burden, and retinal tissue damage. Levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines were determined using quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and ELISA. Flow cytometry was used to assess neutrophil infiltration. Cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP) expression was determined by immunostaining and dot blot.

Results.

Eyes infected with either laboratory or clinical isolates exhibited higher levels of inflammatory mediators at the early stages of infection (≤24 hours) in WT mice than in TLR2−/− or MyD88−/− mice. However, their levels surpassed that of WT mice at the later stages of infection (>48 hours), coinciding with increased bacterial burden and retinal damage. Both TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− retinas produced reduced levels of CRAMP, and its deficiency (Cnlp−/−) rendered the mice susceptible to increased bacterial burden and retinal tissue damage as early as 1 day post infection. Analyses of inflammatory mediators and neutrophil levels in WT versus Cnlp−/− mice showed a trend similar to that observed in TLR2 and MyD88 KO mice. Furthermore, we observed that even a 10-fold lower infective dose of S. aureus was sufficient to cause endophthalmitis in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mice.

Conclusions.

TLR2 and MyD88 signaling plays an important role in protecting the retina from staphylococcal endophthalmitis by production of the antimicrobial peptide CRAMP.

Keywords: CRAMP, endophthalmitis, inflammation, MyD88, retinal damage, Staphylococcus aureus, TLR2

Host innate responses in staphylococcal endophthalmitis are not well understood. To our knowledge, this study is the first to report that TLR2 and MyD88 signaling plays a pivotal role in orchestrating retinal innate immune responses to bacterial endophthalmitis in vivo.

Introduction

Infectious endophthalmitis is a serious and often devastating infection that occurs when microbial pathogens are introduced into the vitreous chamber of the eye following surgical procedures (e.g., cataract surgery) or accidental ocular trauma.1,2 Most cases of culture-positive endophthalmitis are caused by Gram-positive Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, resulting in a greatly diminished or even complete loss of visual acuity, despite therapeutic intervention.3–5 Among the staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for the most severe cases of endophthalmitis. The overall incidence of infectious endophthalmitis has a range of 0.056% to 1.3% following cataract surgery in the aged population.3 However, the increased use of multiple intravitreal injections for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinal diseases has been linked to the increased incidence of endophthalmitis in recent years.6,7 The current treatment for endophthalmitis is intravitreal antibiotic therapy,8 which is very effective against most bacteria but often fails against multi-drug resistant (MDR) ocular pathogens,9,10 which are prevalent in both the hospital and the community.11–13 Several recent studies have reported an increased incidence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) endophthalmitis after cataract surgery.14 Thus, investigating the host response to this disease may provide new alternative therapeutic targets in the prevention and treatment of bacterial endophthalmitis.

Upon entry into the eye, bacteria proliferate rapidly in the nutritionally rich vitreous and cause intraocular inflammation characterized by hypopyon, loss of red reflex, redness of the conjunctiva, and underlying episclera.1,15 Additionally, infection induces the infiltration of immune cells and edema within the retina, and the influx of neutrophils lead to the formation of abscesses.16 Much of the pathology observed in endophthalmitis appears to result from deleterious host responses to the bacteria.4,17 Consequently, the administration of heat-killed S. aureus and its cell wall sacculi has been shown to result in inflammatory responses nearly identical to that seen with live bacteria.18 Although much is known about the cause of infectious endophthalmitis, the induction of retinal immunity, particularly as it relates to protective responses is not well understood.

To identify signaling cascades responsible for orchestrating immune responses in endophthalmitis, over the last 5 years, we investigated the involvement of Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling.3,19–21 Together, our studies revealed that retinal residential cells, the microglia19 and Müller glia,3,22,23 express a full repertoire of TLRs and are the first responders to the pathogen invasion in the vitreous cavity, and elicit innate responses to S. aureus primarily through TLR2. Furthermore, we demonstrated that in vitro–activated retinal glial cells exhibit bactericidal properties, in part due to the production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) including LL-37 (cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide [CRAMP] for mouse).3,23 Similarly, we also showed that intravitreal injection of TLR2 agonist (Pam3Cys) prior to bacterial challenge induced profound protection against staphylococcal endophthalmitis.2 However, these studies did not conclusively prove our hypothesis that the production of AMPs under in vivo conditions is regulated by TLRs and their deficiency worsens disease outcome. Thus, to investigate the protective mechanisms evoked by TLR2 and MyD88 signaling in vivo, here we comprehensively describe the clinical course of S. aureus endophthalmitis and provide confirmatory evidence that induction of TLR2 → MyD88 signaling is critical to protect the retina from staphylococcal endophthalmitis using knockout (KO) mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Ethics Statement

C57BL/6 (wild-type [WT]), TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− (both in B6 background) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA), and the KO mice were bred in-house. CRAMP-deficient (Cnlp−/−) mice were obtained from Richard Gallo, MD, PhD (University of California, San Diego, CA), and were also bred in-house. Animals were housed in a restricted access DLAR facility at the Kresge Eye Institute, maintained in a 12:12 light/dark cycle, and fed LabDiet rodent chow (Labdiet; Pico Laboratory, St. Louis, MO, USA) and water ad libitum. Both male and female mice, 8 to 12 weeks of age, were used in all experiments. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for genotyping to confirm the homozygosity of the littermates. Mice were treated in compliance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and all procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Wayne State University under protocol A 08-02-13.

Induction of Endophthalmitis

Endophthalmitis was induced in WT and KO mice by intravitreal (left eye) inoculation of a laboratory strain (RN6390)2 and two S. aureus endophthalmitis isolates (E311 and E333),24 kindly provided by Regis P. Kowolski, MS, M(ASCP) (Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Uninfected right eyes or eyes injected with sterile PBS served as controls. Clinical examinations were performed using slit lamp and fundus microscopic examination. The ocular disease was graded, and clinical scores ranging from 0 to 4 were assigned using criteria described previously.4,25 At the desired time points post infection, enucleated eyes were subjected to bacterial growth determination, inflammatory cytokine/chemokine assays, polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) infiltration, and histology, as described in the following sections.

Bacterial Burden Estimation

Bacterial burdens in infected eyes of WT, TLR2−/−, MyD88−/−, and Cnlp−/− mice were determined using the standard bacterial plate count method. At the indicated time points, the eyes were enucleated and homogenized in sterile PBS by beating against stainless steel beads in a Tissue lyser (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The homogenate was serially diluted in sterile PBS and plated on tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates. Results were expressed as mean ± SD number of colony-forming units (CFU)/eye.

Cytokine/Chemokine ELISA

Levels of the inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were determined using commercially available ELISA kits. Briefly, 15 μg retinal lysate was used for detection of mouse IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), MIP2, and KC (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Data are mean ± SD pg/mg of retinal tissue lysate.

RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the retinal tissue using TRIzol reagent following the manufacturer's instruction (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Complementary DNA was synthesized using 1.0 μg total RNA using a Maxima first strand cDNA synthesis kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Quantitative RT-PCR was conducted in a StepOnePlus instrument (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY, USA) using cDNA for proinflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL6, MIP2, and KC) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) genes. TaqMan primers and probes (mini-qPCR assay; Prime Time) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). Quantification of gene expression was determined by the comparative ΔΔCT method. Expression levels in the test samples were normalized to the those of endogenous reference GAPDH levels. All assays were performed in triplicate and repeated at least twice.

Dot Blot Analysis

Dot blot analysis for the expression of CRAMP was performed as described previously.23 Briefly, 10 μg total retinal lysates were loaded onto a 0.2 μm Nitrocellulose membrane using a BIO-DOT apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membrane was fixed (10% formaldehyde in Tris-buffered saline [TBS]), blocked (5% skim milk made in TBST [TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20]), and incubated with rabbit anti-mouse CRAMP antibody (Ab) overnight at 4°C. On the following day, the blot was washed and incubated with goat anti-rabbit horseradish-peroxidase (HRP) conjugate and developed using SuperSignal West Femto maximum Sensitivity Substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific) by chemiluminescence, using Kodak image station 4000R Pro molecular imaging system (Carestream Health, Inc., Rochester, NY, USA). Dot intensity was quantified by using ImageJ analysis software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; provided in the public domain by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Immunofluorescence Staining

Retinal cryosections were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT) and washed three times with PBS. The cryosections were then permeabilized by dipping the slides in a gradient of ethanol for 5 minutes each and blocked for 1 hour in blocking buffer (1% [w/v] bovine serum albumin [BSA], 0.05% [v/v] Tween 20 in PBS) at RT. The slides were then incubated overnight with anti-CRAMP Ab at 4°C followed by three washes with PBST. The slides were then incubated for 1h with fluorescent-conjugated secondary Ab (FITC) at RT. After 5 washes in PBS, the slides were mounted in Vectashield anti-fade mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and observed under an Eclipse 90i fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA).

Histological and TUNEL Assays

The embedding, sectioning and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed by Excalibur Pathology, Inc. (Oklahoma City, OK, USA). For TUNEL staining, the eyes were fixed in Tissue-Tek OCT (Sakura, Torrance, CA, USA) and five-micrometer-thick sagittal sections were collected from each eye and mounted onto microscope slides. TUNEL staining was performed on retinal cryosections using ApopTag fluorescein in situ apoptosis detection kit according to the manufacturer's instruction (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Flow cytometry was used to determine the infiltration of PMNs in infected retinas as described previously.23,26,27 Briefly, following euthanasia, the retinas were isolated from the eyes and digested with Accumax (Millipore) for 10 minutes at 37°C. Retinas from two eyes were pooled together to obtain a sufficient number of cells. Following digestion, the retinal tissue was passed through a 23-gauge needle and syringe and filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon, San Jose, CA, USA). The cells were incubated with Fc Block (BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes, followed by a washing step with PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Cells were then incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy5-conjugated CD45, and Ly6G-FITC antibodies (BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes in the dark. After subsequent washing steps, the cells were acquired on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), at the Microscopy, Imaging, and Cytometry Resources Core at Wayne State University (Detroit, MI, USA). Data were analyzed using Flowjo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR, USA).

Statistical Analysis

All data are means ± SD unless indicated otherwise. Prism version 6.2 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. An unpaired, Student's t-test was used to determine statistical significance between groups. One-way ANOVA was used for group comparisons.

Results

S. aureusCauses Increased Retinal Tissue Damage in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mice

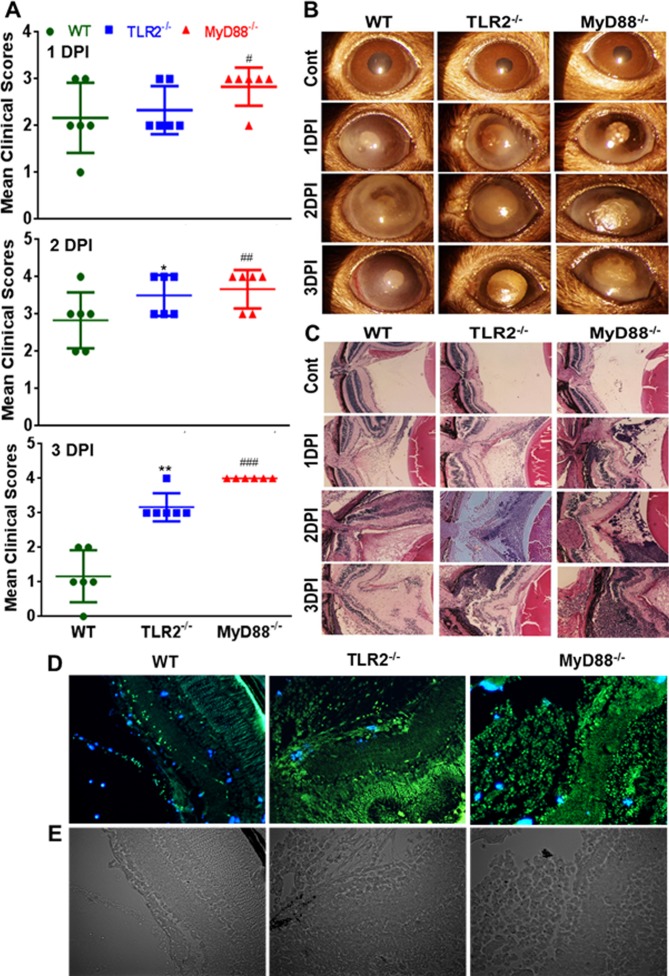

To determine the in vivo roles of TLR2 and MyD88 signaling in the pathogenesis of bacterial endophthalmitis, the eyes of WT (C57BL/6), TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− mice were challenged by inoculation of S. aureus as described previously.2,17,28 Disease severity, as measured by clinical score, showed a time-dependent progression. The average clinical score of TLR2−/− mice did not differ significantly from that of WT mice, whereas MyD88−/− mice had higher clinical scores at 1 day post infection (DPI). At 2 DPI, both TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mice had higher clinical scores than WT mice. This trend continued to 3 DPI, with MyD88−/− having the highest mean clinical scores, followed by TLR2−/− and WT (Fig. 1A). Microscopic examination of the infected eyes coincided with the clinical scores, as shown by increased corneal opacity, hyopyon, and signs of severe inflammation in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mice (Fig. 1B). To further confirm disease severity, histological analysis was performed on infected eyes and showed that at 1 DPI, all WT, TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− mouse eyes exhibited increased cellular infiltration compared to their uninfected (PBS-injected) controls. However, retinal folding was more prominent in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− eyes. These differences were more drastic at 2 and 3 DPI, where both TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− eyes exhibited heavy cellular infiltration, retinal folding, and disorganization of the retinal architecture compared to WT (Fig. 1C). To determine whether increased inflammatory milieu induces retinal cell death, we performed TUNEL staining of infected retinal cryosections. To this end, our data showed an increased number of TUNEL positive (+ve) cells in MyD88−/− and TLR2−/− retinas compared to WT retinas (Fig. 1D). Together, these results indicate that TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mice are more susceptible to S. aureus endophthalmitis.

Figure 1.

TLR2 and MyD88 deficiency rendered eyes susceptible to increased retinal damage following S. aureus infection. (A) Eyes (n = 6) of WT (C57BL/6), TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− mice (both on B6 background) were infected with S. aureus (5000 CFU/eye of strain RN6390) and after 1, 2, and 3 days post infection (DPI), individual eyes were assigned clinical scores (range, 0–4), and data are presented as mean clinical scores (bar with SD). (B) Slit lamp microscopy examination was performed, and photomicrographs were taken of representative eyes. (C) For histological analysis, eyes were enucleated at the indicated time points and subjected to H&E staining. To detect retinal cell death, the eyes were embedded in OCT at 1 DPI and cryosections were subjected to TUNEL staining (blue, DAPI nuclear stain; green, TUNEL+ve cells) (D), and brightfield imaging (E). Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and comparisons were made between WT versus TLR−/− (*) and WT versus MyD88−/− (#); (*#P < 0.05; **##P < 0.005; ###P < 0.0005). Magnification: ×20.

TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− Mouse Eyes Had Increased Bacterial Burden and Inflammatory Mediators

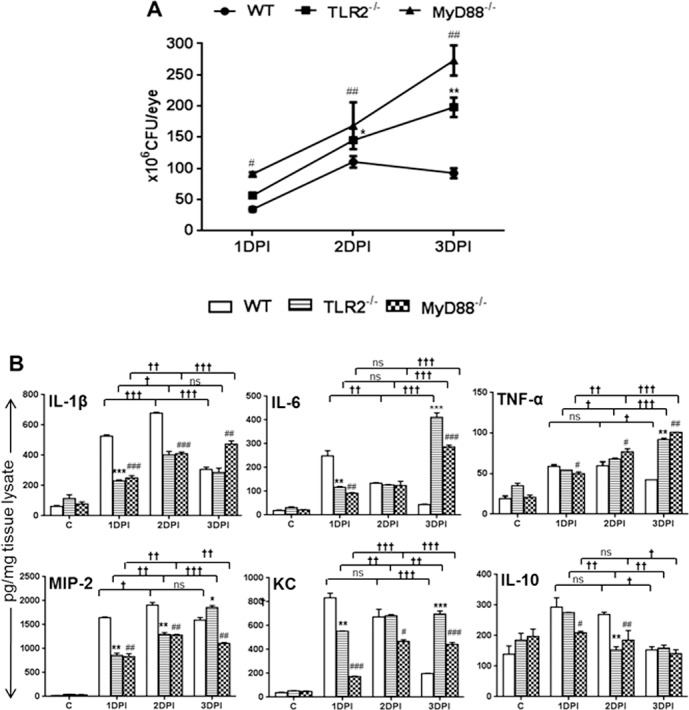

To discover whether TLR2 and MyD88 deficiency influences intraocular bacterial growth, we determined bacterial burden in the infected eyes. To this end, our data indicate a time dependent increase in the bacterial burden in the infected TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mice, compared to WT mice (Fig. 2A). At 1 DPI, the bacterial burden was lowest in WT eyes, followed by TLR2−/− eyes, whereas S. aureus grew rapidly in the eyes of MyD88−/− mice. This trend continued to 2 DPI. However, at 3 DPI, the bacterial load in WT eyes was decreased compared to 2 DPI but still higher than at 1 DPI. In contrast, bacteria continued to grow in the eyes of TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− eyes, and their levels were significantly higher than that in WT eyes at 3 DPI. Analysis of the inflammatory mediators in the same tissue lysates (used for bacterial count) revealed that WT eyes had higher levels of pro-IL-1β, pro-IL-6, pro-TNF-α, pro-MIP-2, and pro-KC and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) mediators at 1 DPI and that their levels gradually declined by 3 DPI. In contrast, the levels of inflammatory mediators in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− eyes were lower at 1 DPI but gradually increased and remained either higher (IL-6, TNF-α, KC, and IL-1β) or similar to (IL-10) that of WT eyes (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− eyes had higher bacterial burdens and increased proinflammatory cytokines at the later stages of infection. Eyes (n = 6) of WT (C57BL/6), TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− mice (both on B6 background) were infected with S. aureus (5000 CFU/eye of strain RN6390). At 1, 2, and 3 days post infection (DPI), the eyes were enucleated and homogenized, and the bacterial burden was estimated by serial dilution plating (A). ELISA was performed to measure the level of inflammatory cytokines, by using tissue lysates (B). Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and comparisons were made between WT versus TLR2−/− (*) and WT versus MyD88−/− (#), (*#P < 0.05; **##P < 0.005; ***###P < 0.0005). One-way ANOVA was used for group comparisons (†P < 0.05; ††P < 0.005; †††P < 0.0005; ns, not significant).

TLR2 and MyD88 Deficiency Delayed Early Innate Responses

The reduced protein levels of inflammatory mediators at 1 DPI (24 hours) in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mice suggest a delay in evoked retinal innate responses in the absence of TLR2/MyD88 signaling. To investigate whether the delay was initiated earlier than 24 hours, we performed qRT-PCR of pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines at 3, 6, and 12 hours of S. aureus infection (Fig. 3). mRNA analysis of both proinflammatory (IL-1β, IL-6, MIP-2, TNF-α, and KC) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) mediators in WT eyes showed time-dependent increases, with the highest levels at 12 hours. In contrast, TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− eyes exhibited lower levels at any given time point, except for of IL-6, KC, and IL-10, whose levels were slightly higher in MyD88−/− eyes than in WT eyes at 3 and 6 hours (for IL-6 only). However, at 12 hours, the levels of investigated inflammatory mediators were significantly lower in both of the KO mice than in WT mice.

Figure 3.

TLR2- and MyD88-deficient eyes had reduced inflammatory cytokine levels at the early stages of infection. Eyes (n = 4) of WT (C57BL/6), TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− mice (both on B6 background) were infected with S. aureus (5000 CFU/eye of strain RN6390), and retinal tissues were harvested at 3, 6, and 12 hours post infection. Following RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis, inflammatory mediators were measured using qRT-PCR. Data are fold changes in comparison with uninfected controls. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and comparisons were made between WT versus TLR−/− (*) and WT versus MyD88−/− (#); (*#P < 0.05; **##P < 0.005; ***###P < 0.0005). One-way ANOVA was used for group comparisons (†P < 0.05; ††P < 0.005; †††P < 0.0005; ns, not significant).

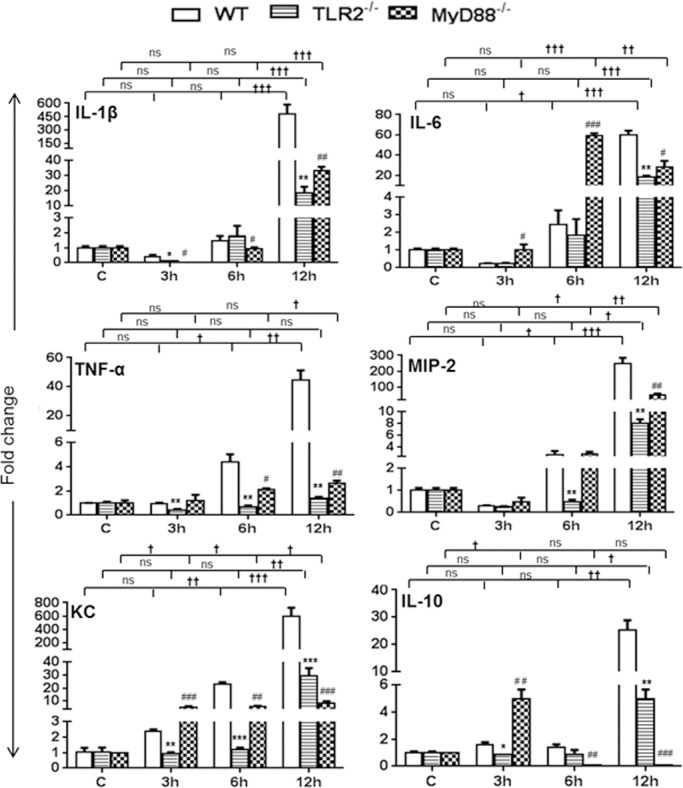

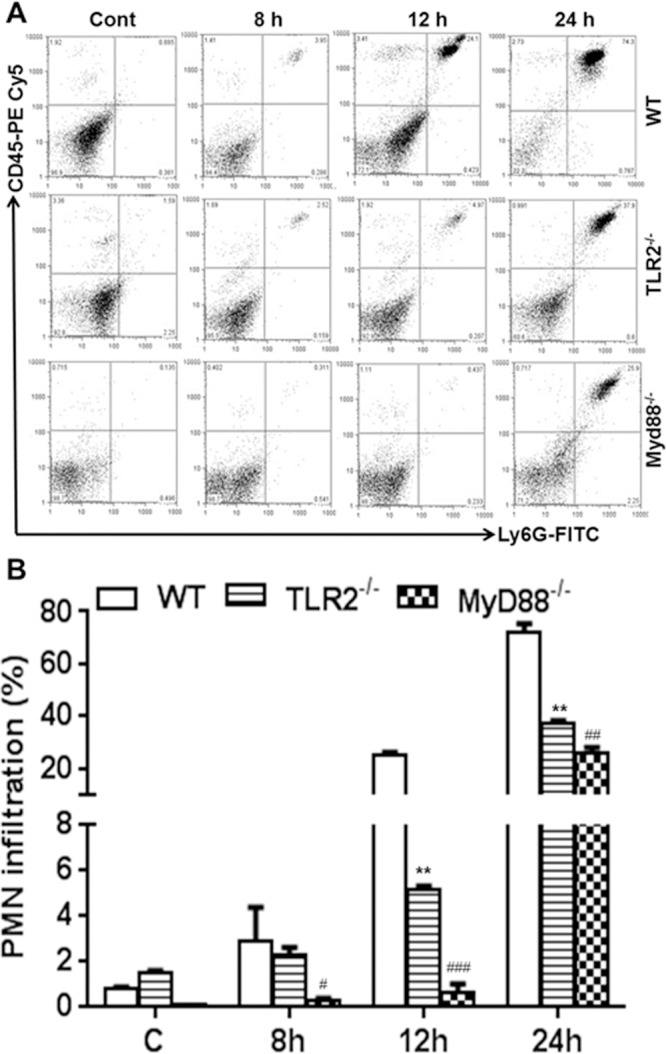

In addition to the production of inflammatory mediators, another early innate response is the influx of neutrophils, the first innate immune cells recruited to the retina in endophthalmitis.26 Therefore, we sought to determine whether TLR2 and MyD88 deficiency had an impact on neutrophil infiltration. Time course analyses revealed significantly higher levels of PMNs in WT (~75%) than in TLR2−/− (~38%) and MyD88−/− (~26%) eyes at 24 hours post infection (Fig. 4). Overall, MyD88−/− eyes exhibited the lowest PMN infiltration at all time points. These results suggest that TLR2 signaling by MyD88 is essential for the early innate responses in staphylococcal endophthalmitis.

Figure 4.

Early neutrophil influx was delayed in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− eyes. Eyes (n = 10) of WT (C57BL/6), TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− mice (both on B6 background) were infected with S. aureus (5000 CFU/eye of strain RN6390), and the vitreous and retina were isolated at the indicated time points. Vitreous and retina from two eyes was pooled to make single-cell suspensions, and cells were stained with anti-CD45 and anti-Ly6G monoclonal antibodies. Post acquisition, cells were size-gated to differentiate them from debris. The percentage of dually positive PMNs was determined by using a CD45-versus-Ly6G dot plot (upper-right quadrant) (A). Bar graph shows cumulative quantitative data from three independent experiments (B). Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and comparisons were made between WT versus TLR−/− (*) and WT versus MyD88−/− (#); (#P < 0.05; **##P < 0.005; ###P < 0.0005).

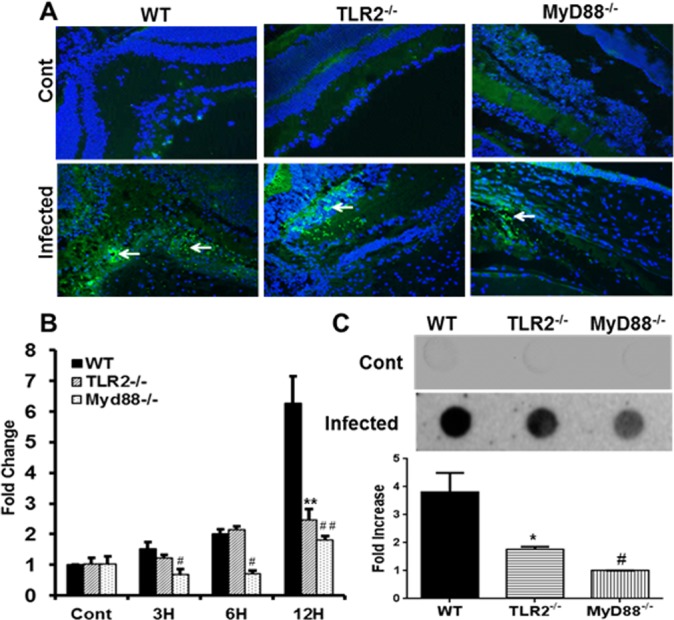

S. aureus-Induced CRAMP Levels Were Lower in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− Mice

We previously showed that S. aureus induces the expression of CRAMP in mouse retina,2 retinal microglia,2,19 and Müller glia.3,23 Moreover, this innate response is mediated in part by TLR2 signaling.19 To examine whether TLR2 deficiency alters CRAMP expression, we determined CRAMP levels in infected WT, TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− eyes (Fig. 5). As expected, immunohistochemical analysis revealed that S. aureus induced CRAMP expression in WT retinas and, to a less extent, in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/−retinas. These findings were further confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 5B) and dot-blot analyses (Fig. 5C). Collectively, these data suggest that TLR2 and MyD88 signaling contribute to retinal CRAMP expression in response to S. aureus infection.

Figure 5.

TLR2- and MyD88-deficient eyes exhibit reduced CRAMP levels. Eyes (n = 4) of WT (C57BL/6), TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− mice (both on B6 background) were infected with S. aureus (5000 CFU/eye of strain RN6390). CRAMP expression in the retina (24 hours post infection) was detected by immunostaining (blue, DAPI nuclear stain; green, CRAMP+ve cells) (A) and dot-blot (C). For quantitative analysis, qRT-PCR was performed at the indicated time points to assess mRNA levels of CRAMP (B). Dots were quantitated by densitometric analysis and are presented as fold increases in comparison to uninfected controls. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and comparisons were made between WT versus TLR2−/− (*) and WT versus MyD88−/− (#); (*#P < 0.05; **##P < 0.005). Magnification: ×20.

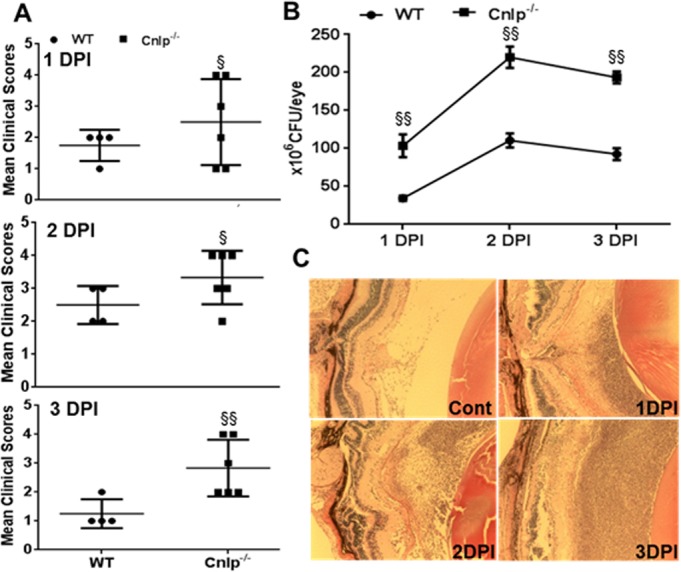

CRAMP-Deficient Mice Are More Susceptible to S. aureus Endophthalmitis

Because CRAMP is a potent AMP with direct bactericidal activity, we hypothesized that the increased bacterial burden seen in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− eyes (Fig. 2) could be due to reduced CRAMP production. To test this, we induced endophthalmitis in CRAMP-deficient (Cnlp−/−) mice and observed that these KO mice developed severe endophthalmitis, as shown by higher clinical scores compared to WT mice at 1, 2, and 3 DPI (Fig. 6A). Similarly, Cnlp−/− eyes had significantly higher bacterial burden (Fig. 6B). Histological analysis of the eyes showed time-dependent increases in retinal damage and heavy cellular and fibrin infiltrates (Fig. 6C), similar to those observed in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mouse eyes (Fig. 1C).

Figure 6.

Cnlp−/− mice show increased susceptibility to staphylococcal endophthalmitis. Eyes (n = 4–6) of WT (C57BL/6) and Cnlp−/− mice (B6 background) were infected with S. aureus (5000 CFU/eye of strain RN6390). At 1, 2, and 3 days post infection (DPI) individual eyes were assigned clinical scores (range, 0–4), and data are mean clinical scores (bar with SD) (A). Bacterial burden was estimated in the eye lysates by serial dilution plating (B). Histological analysis was performed following H&E staining (C). Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and comparisons were made between WT versus Cnlp−/− (§); (§P < 0.05; §§P < 0.005). Magnification: ×20.

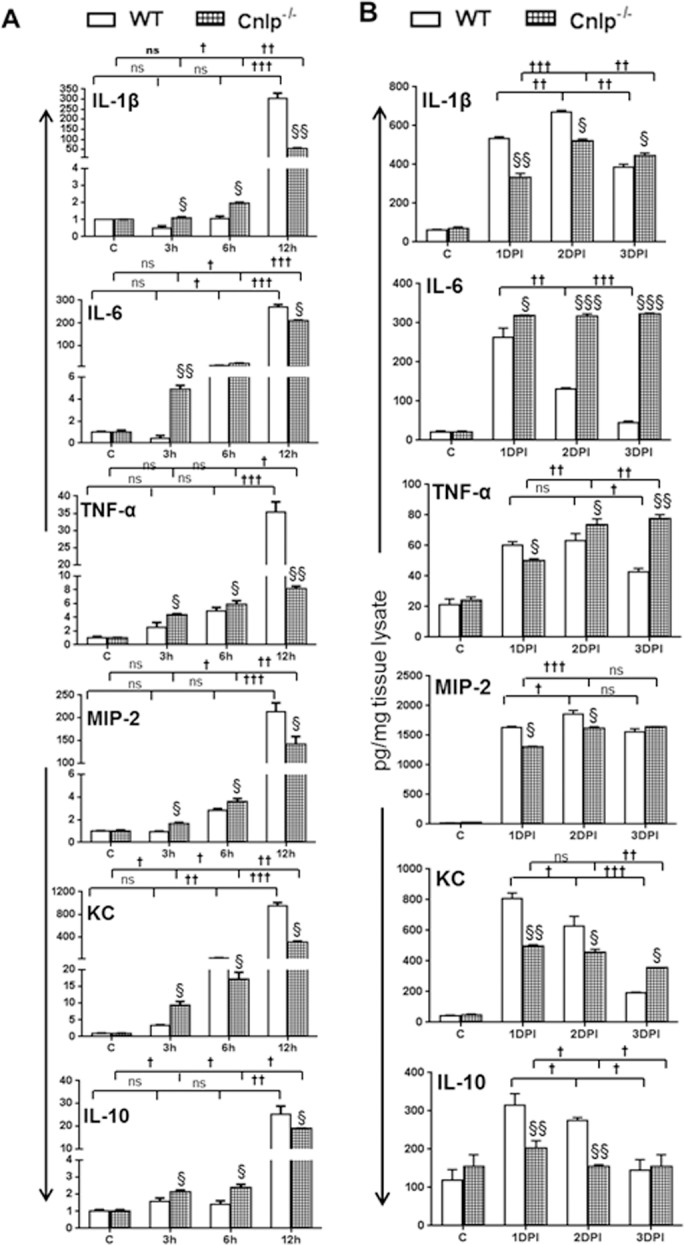

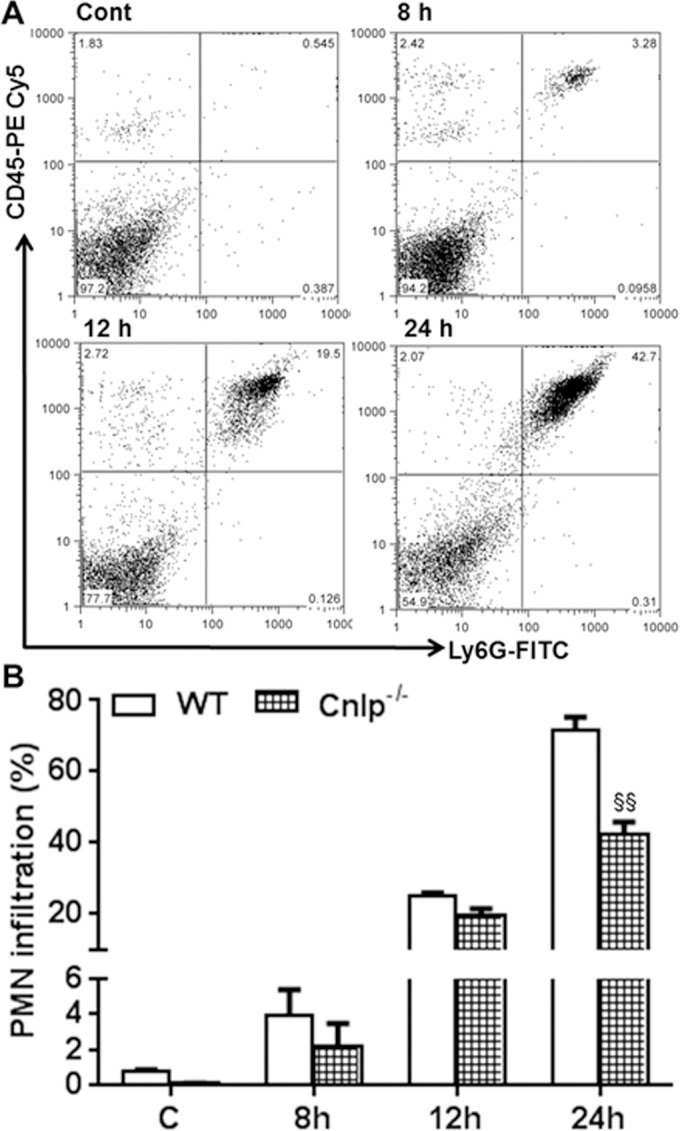

Analysis of the inflammatory mediators showed differential kinetics in Cnlp−/− versus WT mice eyes (Fig. 7). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed the increased mRNA expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, MIP-2, KC, and IL-10 in Cnlp−/− compared to WT eyes at 3 and 6 hours post S. aureus infection; however, their levels were reduced at 12 hours in all cases (Fig. 7A). The quantification of these cytokines at the protein level showed reduced levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, MIP-2, KC, and IL-10 at 1 DPI, and the trend continued to 2 DPI, with the exception of TNF-α, whose levels were slightly increased. At 3 DPI, the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and KC were higher in Cnlp−/− eyes, whereas the levels of MIP-2 and IL-10 were similar to those of WT eyes (Fig. 7B). Flow cytometry analysis revealed slightly reduced but not statistically significant PMN infiltration at 8 and 12 hours post S. aureus infection in Cnlp−/− mouse eyes. However, PMN levels were significantly lower at 24 hours (Fig. 8).

Figure 7.

Cnlp−/− eyes exhibit persistently higher inflammatory mediators. Eyes (n = 4) of WT (C57BL/6) and Cnlp−/− mice (B6 background) were infected with S. aureus (5000 CFU/eye of strain RN6390). The level of inflammation was monitored in infected eyes at the transcript level by qRT-PCR (A) and at the protein level by ELISA (B). Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and comparisons were made between WT versus Cnlp−/− (§); (§P < 0.05; §§P < 0.005; §§§P < 0.0005). One-way ANOVA was used for group comparisons (†P < 0.05; ††P < 0.005; †††P < 0.0005; ns, not significant).

Figure 8.

Cnlp−/− mice exhibit reduced PMN infiltration at the early stages of infection. Eyes (n = 8) of WT (C57BL/6) and Cnlp−/− mice (B6 background) were infected with S. aureus (5000 CFU/eye of strain RN6390). Polymorphonuclear neutrophil infiltration was determined using flow cytometry (A), as described in the legend to Figure 4. Bar graph shows cumulative quantitative data from three independent experiments (B). Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and comparisons were made between WT versus Cnlp−/− (§); (§P < 0.05; §§P < 0.005).

A Lower Dose of S. aureus Causes Endophthalmitis in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− Mice

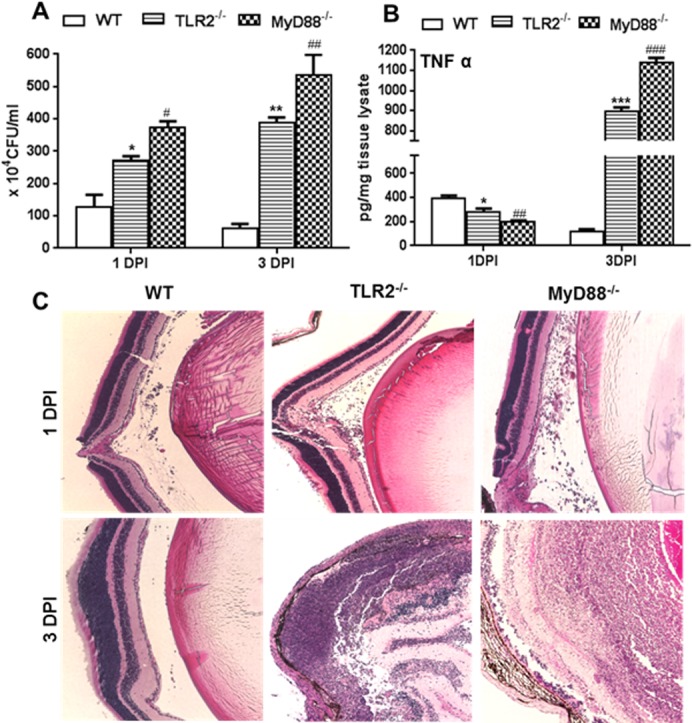

Previous studies have shown that intravitreal injection of 500 CFU of S. aureus causes transient inflammation in WT mice; however, the bacteria are cleared by 3 DPI, and inflammation is resolved.4,17,28 Having shown the increased susceptibility of TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mice by using a dose of 5000 CFU/eye, we sought to determine whether 500 CFU/eye, a 10-fold lower dose could cause endophthalmitis in these KO mice. To this end, our data showed that, similar to the response to the 5000 CFU dose (Fig. 2A), intravitreal injection of 500 CFU of S. aureus resulted in an increased bacterial burden in both TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mouse eyes at 1 and 3 DPI, whereas their viable counts were significantly reduced at 3 DPI in WT mice (Fig. 9A). Analysis of inflammatory mediators (e.g., TNF-α) showed decreased levels at 1 DPI in KO mice but significantly elevated levels at 3 DPI (Fig. 9B). Histological analysis showed no significant damage in WT retinas at 3 DPI. In contrast, increased retinal damage with heavy cellular infiltration was evident in TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− eyes at 3 DPI (Fig. 9C).

Figure 9.

TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− mice developed endophthalmitis with lower infectious doses of S. aureus. Eyes (n = 4) of WT (C57BL/6), TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− mice (both on B6 background) were infected with S. aureus (500 CFU/eye of strain RN6390). At the indicated time points, infected eyes were subjected to bacterial load estimation by serial dilution plating (A), ELISA for proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α (B), and histological analysis (C), as described in legends to figures. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and comparisons were made between WT versus TLR−/− (*) and WT versus MyD88−/− (#); (#P < 0.05; **##P < 0.005; ###P < 0.0005). Magnification: ×20.

TLR2, MyD88, and CRAMP Deficiency Impairs Retinal Innate Responses To S. aureus Endophthalmitis Isolates

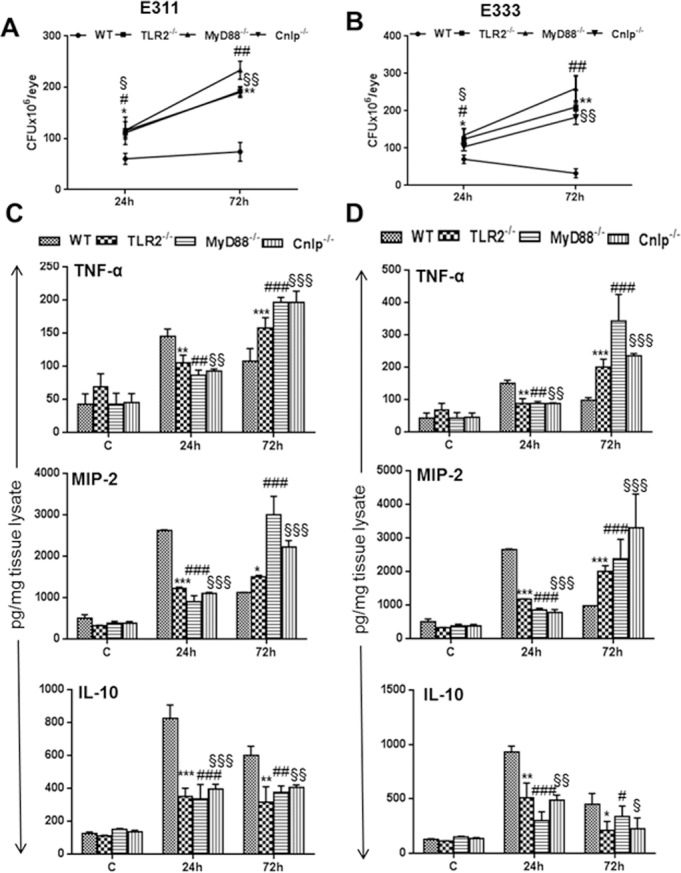

Having shown the impact of loss of TLR2 and MyD88 signaling in initiation of retinal innate responses by using the S. aureus laboratory strain RN6390, we next sought to compare innate responses to human S. aureus endophthalmitis isolates.24 To this end, our results indicated that overall, the KO mice exhibited similar disease progression with minor difference (in terms of levels) following infection with clinical isolates, as observed with RN6390 (Fig. 10). Briefly, the bacterial burdens in all KO eyes infected with the E311 strain (Fig. 10A) or the E333 strain (Fig. 10B) were higher than in WT mice at both 24 hours and 72 hours post infection. Interestingly, the clinical isolates (E333 being slightly more) induced higher levels of inflammatory mediators than RN6390 in both WT and KO mice (compare Fig. 2B and Figs. 10C, 10D). The comparison of individual clinical isolates in WT versus KO mice revealed a similar trend, that is, reduced levels of TNFα and MIP2 at 24 hours and significantly higher levels at 72 hours for both E311- and E333-infected eyes (Fig. 10C and D). However, IL-10 levels remained lower at both 24 hours and 72 hours post infection.

Figure 10.

TLR2−/−, MyD88−/−, and Cnlp−/− eyes exhibit increased bacterial burdens and inflammatory mediators following challenge with endophthalmitis-inducing S. aureus isolates. Eyes (n = 6) of WT (C57BL/6), TLR2−/−, MyD88−/−, and Cnlp−/− mice were infected with clinical grade endophthalmitis S. aureus strains E311 (A, C) and E333 (B, D). At 24 and 72 hours post infection, eyes were enucleated and homogenized, and the bacterial burden was estimated by serial dilution plating (A, B). ELISA was performed to measure the level of inflammatory cytokines by using tissue lysates (C, D). Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and comparisons were made between WT versus TLR2−/− (*), WT versus MyD88−/− (#), and WT versus Cnlp−/− (§);(*#§P < 0.05; **##§§P < 0.005; ***###§§§P < 0.0005).

Discussion

Previous studies from our laboratory and others have shown that the host innate immune responses generated by TLRs are critical in defending the eye from ocular pathogens, including S. aureus.29–33 We postulated that, in an immune-privileged tissue such as the retina, the lack of this innate system gives an advantage to pathogens by allowing them to grow inside the eye, which leads to retinal damage and permanent vision loss. Here, we demonstrated that TLR2/MyD88-dependent signals are responsible for both the production of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines and the infiltration of PMNs at the early stages of staphylococcal endophthalmitis. The lack of these innate responses impedes bacterial clearance and contributes to the increased inflammation and retinal tissue damage seen in TLR2 and MyD88 KO mice at the later stages of infection. Most importantly, even a lower infectious dose of S. aureus was able induce endophthalmitis in these KO mice. Furthermore, our data revealed that in vivo TLR2/MyD88 signaling regulates S. aureus-induced production of CRAMP in the retina and that the deficiency of this signaling renders eyes more susceptible to staphylococcal endophthalmitis. Collectively, these findings indicate that the activation of TLR2 → MyD88 signaling evokes protective innate responses in staphylococcal endophthalmitis and that targeting this signaling cascade may lead to novel therapeutic agents for the prevention or treatment of bacterial endophthalmitis.

Our laboratory has focused on understanding the host innate response to bacterial endophthalmitis and on identifying pathways that lead to intraocular inflammation and cellular infiltration in the vitreous cavity and the loss of retinal function. We demonstrated that S. aureus virulence factors activate TLR2 on retinal microglia19 and Müller glia,3,20 which produce CXC chemokines, which then facilitate neutrophil recruitment to the retina to limit bacterial growth.34 Moreover, the activation of TLR2 prior to S. aureus challenge was shown to attenuate the development of endophthalmitis in WT mice, suggesting its protective role.2 In the current study, we demonstrated that TLR2 deficiency resulted in worse disease outcome, further confirming the protective role of TLR2 in staphylococcal endophthalmitis. Time course studies revealed delayed production of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines at the early stages of infection in TLR2−/− KO mice. As these inflammatory mediators are required for the trafficking of innate immune cells,35 TLR2−/− eyes exhibited reduced PMN infiltration. The crucial role of PMNs in host immune responses against various bacterial infections, including endophthalmitis, has been demonstrated in multiple in vivo models.17,25,26,29,33,36 Although the mechanisms regulating PMN infiltration in bacterial endophthalmitis are not well understood, recent studies have demonstrated that the lack of TLR signaling influences PMN recruitment to the retina in experimental Klebsiella pneumoniae33 and Bacillus cereus29,30 endophthalmitis. Here, we demonstrate that TLR2 plays an important role in initiating PMN infiltration in S. aureus endophthalmitis and that its deficiency delayed this response.

Earlier studies have shown that TLR2-deficient mice have increased mortality compared to WT mice in systemic S. aureus infection, which was attributed to a higher bacterial burden and dysregulated inflammatory responses.37,38 In addition to systemic infections, staphylococci are the leading cause of bacterial endophthalmitis and the mechanisms of in vivo TLR2 signaling, which have not been investigated in the setting of staphylococcal endophthalmitis. However, in a recent study by Novosad et al.,29 TLR2 deficiency did not seem to affect the intraocular growth of bacteria in a B. cereus endophthalmitis model but significantly reduced the levels of PMNs and proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines at 4, 8, and 12 hours post infection. These findings are consistent with our data at the early stages, that is, 12 to 24 hours of S. aureus infection. However, it should be noted that, in contrast to S. aureus, endophthalmitis caused by B. cereus progresses faster with massive destruction of the retina within 20 hours.25 The differences observed between the pathogenicity of S. aureus and that of B. cereus could be due to the expression of different virulence factors such as flagella, which can increase the motility39 as well as engage TLR5 activation30 to amplify intraocular inflammation and retinal damage in bacillus endophthalmitis. To determine whether the retinal innate responses observed in this study are specific to the laboratory strain (RN6390), we tested two S. aureus endophthalmitis isolates (Fig. 10) and observed no significant differences in innate responses to laboratory versus to clinical isolates, despite the fact that clinical isolates were multidrug resistant (MDR).24 Together, these findings suggest that activating TLR2/MyD88 signaling could provide protection against endophthalmitis in humans caused by staphylococci regardless of their antibiotic resistance. In contrast, our recent study demonstrated that MDR ocular isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii40 caused aggressive endophthalmitis in the mouse model,26 supporting the notion that bacterial virulence factors determine the outcome of endophthalmitis in a pathogen-specific manner.18

TLR2 has been implicated in the recognition of a variety of microbial products primarily from Gram-positive bacteria including S. aureus.21,41,42 The wide range of TLR2 ligand specificity may be attributed to its ability to form heterodimers with TLR-1 and TLR-6.43 However, regardless of ligand specificity, TLR2 mediates its signaling primarily through the common adaptor molecule MyD88. Here, we showed that MyD88 deficiency worsens disease outcome in staphylococcal endophthalmitis. In comparison with TLR2−/− eyes, MyD88−/− eyes had higher bacterial burdens, increased tissue damage, and higher inflammation specifically at the later stages of infection (Figs. 1–5). These data suggest that MyD88 is essential for TLR2 and potentially other TLRs to function in eliciting early innate defense against S. aureus infection in an endophthalmitis setting. The relatively higher susceptibility of MyD88−/− to S. aureus endophthalmitis could be due to impairment of IL-1R signaling, as MyD88 is a key mediator of IL-1 and IL-18 responses.43–45 Future studies will determine whether secondary signaling through IL-1R/MyD88 is beneficial or detrimental in staphylococcal endophthalmitis.

The downstream effects of TLR signaling involve the production of inflammatory mediators and AMPs.21 Cathelicidins are an important group of AMPs in exerting protective effects in various bacterial infection models, including the eye.46,47 Our previous in vitro studies have demonstrated that S. aureus infection induces the expression of CRAMP in retinal microglia and Müller glia and that their conditioned medium possess antistaphylococcal activities.3,19,23 In order to investigate the signaling mechanisms for in vivo production of CRAMP in staphylococcal endophthalmitis, we assessed the expression of CRAMP in WT, TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− mice and observed reduced CRAMP production in both of the KO mice. Moreover, we demonstrated that the induced production of CRAMP contributes to bacterial clearance in endophthalmitis, as shown by an increased S. aureus burden in Cnlp−/− eyes. At early stages of infection, Cnlp−/− mice have similar levels of PMN infiltration in the retina, whereas at later stages of infection, Cnlp−/− mice have fewer PMNs than WT mice. It is well known that in addition to antimicrobial actions, LL37/CRAMP possess immunomodulatory properties.48 For example, CRAMP has been shown to have a direct effect on the migration of immune cells, including neutrophils, which in turn produce CRAMP in an autocrine manner.49,50,51 An earlier study showed that LL-37 induces the generation of reactive oxygen species from human neutrophils, which enhances their antimicrobial properties.52 However, PMNs from CRAMP-deficient mice exhibited increased TNF-α production and decreased antimicrobial activity in response to bacterial challenge.51 Our data also showed higher levels of production of TNF-α and IL-6 at 3 DPI in Cnlp−/− mice. Based on our observations, we postulate that the lack of CRAMP produced by infiltrating neutrophils at the site of infection may have distorted the feedback loop, resulting in increased inflammation and poor prognosis of endophthalmitis in Cnlp−/− mice. Together, these data suggest an important role for cathelicidins in retinal innate defense, by modulating the response of neutrophils and the release of inflammatory mediators.

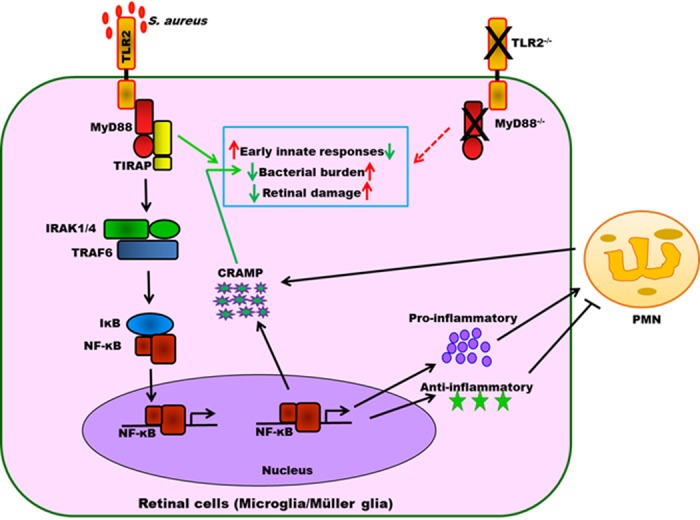

In summary, these results indicate that signals emanating from TLR2 by MyD88 are involved in orchestrating several aspects of the retinal immune response to S. aureus endophthalmitis, including the production of early inflammatory mediators, bacterial containment, and the production of AMPs (Fig. 11). In the absence of TLR2 and MyD88, these responses become dysregulated, leading to increased bacterial burdens and persistent inflammation.

Figure 11.

Role of TLR2 and MyD88 signaling in orchestrating retinal innate responses in staphylococcal endophthalmitis. During endophthalmitis, S. aureus proliferates inside the vitreous and releases its virulence factors (toxins, cell wall components), which, upon recognition by TLR2-expressing microglia and Müller glia, initiate early innate responses by its downstream adaptor molecule MyD88. These innate responses are critical in the recruitment of PMNs to the retina and the production of CRAMP, which together inhibit bacterial growth in the eye. In the absence of TLR2/MyD88 signaling, bacteria grow unchecked, leading to increased inflammation and tissue destruction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Regis P. Kowolski, MD, PhD (Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pittsburgh, PA, USA), for providing clinical S. aureus isolates. We also thank Mallika Gupta and Travis Kochan for their technical support and Bruce Rottmann for critical reading of the manuscript.

Supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant EY19888 and a Research to Prevent Blindness special scholar award (RPB). The microscopy, imaging, and cytometry resource core was supported in part by NIH Center Grant P30EY004068 (Linda D. Hazlett, PhD, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, USA).

References

- 1. Kernt M, Kampik A. Endophthalmitis: pathogenesis, clinical presentation, management, and perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010; 4: 121–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumar A, Singh CN, Glybina IV, Mahmoud TH, Yu FS. Toll-like receptor 2 ligand-induced protection against bacterial endophthalmitis. J Infect Dis. 2010; 201: 255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shamsuddin N, Kumar A. TLR2 mediates the innate response of retinal Muller glia to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2011; 186: 7089–7097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whiston EA, Sugi N, Kamradt MC, et al. alphaB-crystallin protects retinal tissue during Staphylococcus aureus-induced endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 2008; 76: 1781–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Callegan M, Gilmore M, Gregory M, et al. Bacterial endophthalmitis: therapeutic challenges and host-pathogen interactions. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007; 26: 189–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Novosad BD, Callegan MC. Severe bacterial endophthalmitis: towards improving clinical outcomes. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2010; 5: 689–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sadaka A, Durand M, Gilmore M. Bacterial endophthalmitis in the age of outpatient intravitreal therapies and cataract surgeries: host-microbe interactions in intraocular infection. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012; 31: 316–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yam JC, Kwok AK. Update of the management of postoperative endophthalmitis. Hong Kong Med J. 2004; 10: 337–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McDonald M, Blondeau JM. Emerging antibiotic resistance in ocular infections and the role of fluoroquinolones. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010; 36: 1588–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Talreja D, Muraleedharan C, Gunathilaka G, et al. Virulence properties of multidrug resistant ocular isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Curr Eye Res. 2014; 39: 695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Major JC Jr, Engelbert M, Flynn HW Jr, Miller D, Smiddy WE, Davis JL. Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis: antibiotic susceptibilities, methicillin resistance, and clinical outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010; 149: 278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Olson R, Donnenfeld E, Bucci FA Jr, et al. Methicillin resistance of Staphylococcus species among health care and nonhealth care workers undergoing cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010; 4: 1505–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zaidi T, Yoong P, Pier GB. Staphylococcus aureus corneal infections: effect of the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) and antibody to PVL on virulence and pathology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 4430–4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deramo VA, Lai JC, Winokur J, Luchs J, Udell IJ. Visual outcome and bacterial sensitivity after methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-associated acute endophthalmitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008; 145: 413–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Callegan MC, Engelbert M, Parke DW II, Jett BD, Gilmore MS. Bacterial endophthalmitis: epidemiology, therapeutics, and bacterium-host interactions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002; 15: 111–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leid JG, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME, Gilmore MS, Engelbert M. Immunology of staphylococcal biofilm infections in the eye: new tools to study biofilm endophthalmitis. DNA Cell Biol. 2002; 21: 405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sugi N, Whiston EA, Ksander BR, Gregory MS. Increased resistance to Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis in BALB/c mice: Fas ligand is required for resolution of inflammation but not for bacterial clearance. Infect Immun. 2013; 81: 2217–2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Callegan MC, Booth MC, Jett BD, Gilmore MS. Pathogenesis of gram-positive bacterial endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 1999; 67: 3348–3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kochan T, Singla A, Tosi J, Kumar A. Toll-like receptor 2 ligand pretreatment attenuates retinal microglial inflammatory response but enhances phagocytic activity toward Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2012; 80: 2076–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumar A, Pandey RK, Miller LJ, Singh PK, Kanwar M. Muller glia in retinal innate immunity: a perspective on their roles in endophthalmitis. Crit Rev Immunol. 2013; 33: 119–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pandey RK, Yu FS, Kumar A. Targeting toll-like receptor signaling as a novel approach to prevent ocular infectious diseases. Indian J Med Res. 2013; 138: 609–619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kumar A, Shamsuddin N. Retinal Muller glia initiate innate response to infectious stimuli via Toll-like receptor signaling. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e29830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Singh P, Shiha M, Kumar A. Antibacterial responses of retinal Müller glia: production of antimicrobial peptides, oxidative burst and phagocytosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2014; 11: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rarey KA, Shanks RM, Romanowski EG, Mah FS, Kowalski RP. Staphylococcus aureus isolated from endophthalmitis are hospital-acquired based on Panton-Valentine leukocidin and antibiotic susceptibility testing. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2012; 28: 12–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ramadan RT, Ramirez R, Novosad BD, Callegan MC. Acute inflammation and loss of retinal architecture and function during experimental Bacillus endophthalmitis. Curr Eye Res. 2006; 31: 955–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Talreja D, Kaye KS, Yu FS, Walia SK, Kumar A. Pathogenicity of ocular isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii in a mouse model of bacterial endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55: 2392–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singh PK, Donovan DM, Kumar A. Intravitreal injection of the chimeric phage endolysin Ply187 protects mice from Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014; 58: 4621–4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Engelbert M, Gilmore MS. Fas ligand but not complement is critical for control of experimental Staphylococcus aureus Endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 2479–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Novosad BD, Astley RA, Callegan MC. Role of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 in experimental Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis. PLoS One. 2011; 6: e28619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parkunan SM, Astley R, Callegan MC. Role of TLR5 and flagella in bacillus intraocular infection. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e100543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kumar A, Hazlett LD, Yu FS. Flagellin suppresses the inflammatory response and enhances bacterial clearance in a murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Infect Immun. 2008; 76: 89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun Y, Hise AG, Kalsow CM, Pearlman E. Staphylococcus aureus-induced corneal inflammation is dependent on Toll-like receptor 2 and myeloid differentiation factor 88. Infect Immun. 2006; 74: 5325–5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hunt JJ, Astley R, Wheatley N, Wang JT, Callegan MC. TLR4 Contributes to the host response to Klebsiella intraocular infection. Curr Eye Res. 2014; 39: 790–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Giese MJ, Sumner HL, Berliner JA, Mondino BJ. Cytokine expression in a rat model of Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998; 39: 2785–2790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lacy P, Stow JL. Cytokine release from innate immune cells: association with diverse membrane trafficking pathways. Blood. 2011; 118: 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Giese MJ, Rayner SA, Fardin B, et al. Mitigation of neutrophil infiltration in a rat model of early Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44: 3077–3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yimin Kohanawa M, Zhao S, et al. Contribution of Toll-like receptor 2 to the innate response against Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e74287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Akira S. Cutting edge: TLR2-deficient and MyD88-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Immunol. 2000; 165: 5392–5396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Callegan MC, Novosad BD, Ramirez R, Ghelardi E, Senesi S. Role of swarming migration in the pathogenesis of bacillus endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 4461–4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Talreja D, Muraleedharan C, Gunathilaka G, et al. Virulence properties of multidrug resistant ocular isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Curr Eye Res. 2014; 39: 695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li Q, Kumar A, Gui JF, Yu FS. Staphylococcus aureus lipoproteins trigger human corneal epithelial innate response through toll-like receptor-2. Microb Pathog. 2008; 44: 426–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pietrocola G, Arciola CR, Rindi S, et al. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in innate immune defense against Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Artif Organs. 2011; 34: 799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takeda K, Akira S. TLR signaling pathways. Semin Immunol. 2004; 16: 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Miller LS, Cho JS. Immunity against Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011; 11: 505–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Warner N, Núñez G. MyD88: a critical adaptor protein in innate immunity signal transduction. J Immunol. 2013; 190: 3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kumar A, Gao N, Standiford TJ, Gallo RL, Yu FS. Topical flagellin protects the injured corneas from Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Microbes Infect. 2010; 12: 978–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huang LC, Reins RY, Gallo RL, McDermott AM. Cathelicidin-deficient (Cnlp−/−) mice show increased susceptibility to Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 4498–4508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Amatngalim GD, Nijnik A, Hiemstra PS, Hancock RE. Cathelicidin peptide LL-37 modulates TREM-1 expression and inflammatory responses to microbial compounds. Inflammation. 2011; 34: 412–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kurosaka K, Chen Q, Yarovinsky F, Oppenheim JJ, Yang D. Mouse cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide chemoattracts leukocytes using formyl peptide receptor-like 1/mouse formyl peptide receptor-like 2 as the receptor and acts as an immune adjuvant. J Immunol. 2005; 174: 6257–6265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Doss M, White MR, Tecle T, Hartshorn KL. Human defensins and LL-37 in mucosal immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2010; 87: 79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alalwani SM, Sierigk J, Herr C, et al. The antimicrobial peptide LL-37 modulates the inflammatory and host defense response of human neutrophils. Eur J Immunol. 2010; 40: 1118–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zheng Y, Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, et al. Cathelicidin LL-37 induces the generation of reactive oxygen species and release of human α-defensins from neutrophils. Br J Dermatol. 2007; 157: 1124–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]