Abstract

Objectives

Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) is an important healthcare-associated pathogen. We evaluated the impact of CRKP strain type and treatment on outcomes of patients with CRKP bacteriuria.

Patients and methods

Physician-diagnosed CRKP urinary tract infection (UTI)—defined as those patients who received directed treatment for CRKP bacteriuria—was studied in the multicentre, prospective Consortium on Resistance against Carbapenems in Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRaCKle) cohort. Strain typing by repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (rep-PCR) was performed. Outcomes were classified as failure, indeterminate or success. Univariate and multivariate ordinal analyses to evaluate the associations between outcome, treatment and strain type were followed by binomial analyses.

Results

One-hundred-and-fifty-seven patients with physician-diagnosed CRKP UTI were included. After adjustment for CDC/National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN)-defined UTI, critical illness and receipt of more than one active antibiotic, patients treated with aminoglycosides were less likely to fail therapy [adjusted OR (aOR) for failure 0.34, 95% CI 0.15–0.73, P = 0.0049]. In contrast, patients treated with tigecycline were more likely to fail therapy (aOR for failure 2.29, 95% CI 1.03–5.13, P = 0.0425). Strain type data were analysed for 55 patients. The predominant clades were ST258A (n = 18, 33%) and ST258B (n = 26, 47%). After adjustment for CDC/NHSN-defined UTI and use of tigecycline and aminoglycosides, infection with strain type ST258A was associated with clinical outcome in ordinal analysis (P = 0.0343). In multivariate binomial models, strain type ST258A was associated with clinical failure (aOR for failure 5.82, 95% CI 1.47–28.50, P = 0.0113).

Conclusions

In this nested cohort study of physician-diagnosed CRKP UTI, both choice of treatment and CRKP strain type appeared to impact on clinical outcomes.

Keywords: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, MDR, UTIs, aminoglycosides, tigecycline

Introduction

Infections with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) represent a growing threat to patients in the USA and worldwide.1 The treatment of these infections is problematic, as few therapeutic options are available.2 Antibiotics that may retain in vitro activity against CRKP include polymyxins such as colistin, tigecycline and aminoglycosides. Novel therapies that promise to be effective against CRKP, such as ceftazidime/avibactam, plazomicin and BAL30072, are still far from the armamentarium of the physician.

Most CRKP in the USA produce carbapenemases of the K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) family. In addition, metallo-β-lactamases such as New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM-1) are prevalent causes of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae in other parts of the world, and are beginning to be reported in the USA as well.3,4 The most common endemic strain of CRKP is ST258 by MLST, which can be further subdivided into clinically and microbiologically distinct clades by the use of high-resolution restriction mapping, repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (rep-PCR) and whole-genome sequencing.3,5 In most patients who have CRKP isolated during their hospitalization, CRKP is found in urine cultures.3 About a third of patients with CRKP bacteriuria meet CDC/National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) criteria for urinary tract infection (UTI).3,6 However, these criteria were primarily designed for surveillance purposes, and many patients with CRKP bacteriuria who do not meet these criteria are thought to have UTI by their providers and receive directed treatment. To address this point, we describe the impact of various treatment regimens on the outcomes of patients who were treated with antibiotics directed against CRKP—colistin, tigecycline, aminoglycosides, fosfomycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole—for CRKP bacteriuria, while adjusting for the presence of UTI as defined by CDC/NHSN. Our primary aims were to evaluate the impact of treatment and strain type on outcomes in physician-diagnosed CRKP UTI.

Patients and methods

Patients

The multicentre, prospective Consortium on Resistance against Carbapenems in Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRaCKle) study was described previously.3 The current study represents a nested cohort within CRaCKle. All hospitalized patients who had a urine culture that grew CRKP and who received active treatment within 7 days of their first positive urine culture during their hospitalization were included if their index hospitalization began and ended in the study period, 24 December 2011 to 1 October 2013. Patients were included once at the time of their first episode of treated CRKP bacteriuria. The institutional review boards of all health systems involved approved the study.

Definitions

The index hospitalization was designated as the first hospital stay within the study period during which CRKP was isolated from the urine followed by active treatment within 7 days. Active treatment was defined as receipt of an aminoglycoside, colistin, tigecycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or fosfomycin, unless in vitro resistance was documented to that antimicrobial in the patient's isolate, following CLSI (aminoglycosides, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and fosfomycin) and EUCAST (colistin and tigecycline) guidelines. The base of the regimen was assigned as follows: any regimen that contained an aminoglycoside was deemed aminoglycoside-based; any regimen that contained colistin, but not an aminoglycoside, was deemed colistin-based; and any regimen that contained tigecycline, but not colistin or an aminoglycoside, was deemed tigecycline-based. All other regimens were classified as ‘other’.

Criteria as outlined by CDC/NHSN were used to define UTI and asymptomatic bacteraemic UTI (ABUTI); these two categories were grouped together as CDC/NHSN-defined UTI for analysis purposes.6 Non-physiological urinary drainage was defined as the presence of an indwelling urinary catheter, permanent urinary diversion or intermittent urinary catheterization. All other patients were considered to have physiological urinary drainage.

Critical illness was defined as a Pitt bacteraemia score ≥4 points on the day of the index urine culture.7 Treatment failure was defined as patients who had recurrent CRKP isolated from the urine at least 7 days after their index culture. In addition, those who did not survive their index hospitalization (death or discharge to hospice) were considered treatment failures. Treatment success was defined as patients who had a negative urine culture documented after their index culture and who did not meet any of the criteria for treatment failure. Treatment outcome was deemed indeterminate in those patients who did not meet criteria for success or failure.

Microbiology

CRKP is defined as K. pneumoniae isolates with non-susceptibility to the following carbapenems as per CLSI guidelines: meropenem, imipenem or ertapenem.8 Bacterial identification and routine antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed with MicroScan (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) or Vitek 2 (bioMérieux), supplemented by a GN4F Sensititre tray (Thermo Fisher) to confirm carbapenem results and to test tigecycline susceptibility.

Detection of carbapenemases in CRKP and strain typing

Detection of carbapenemase genes and rep-PCR strain typing was performed as previously described.3 Briefly, PCR amplification of blaKPC, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaIMP and blaOXA-48 genes was conducted using established primers and methods; amplicons were sequenced at a commercial sequencing facility (MCLAB, San Francisco, CA, USA) and analysed.9,10 rep-PCR was performed using the DiversiLab strain typing system (Bacterial BarCodes, bioMérieux, Athens, GA, USA). Isolates with ≥95% similarity were considered to be of the same rep-PCR type. MLST was performed on CRKP isolates from the predominant rep-PCR types, as previously described.11 Sequences of seven housekeeping genes (rpoB, gapA, mdh, pgi, phoE, infB and tonB) were compared with the MLST database (http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/genopole/PF8/mlst).

Analysis

The primary outcome was analysed as an ordinal variable in the following order: failure, indeterminate, success. Ordinal logistic regression was used to estimate associations between outcomes and microbiological and clinical variables. For all models, ordinal lack-of-fit testing was performed to rule out a poorly fitted model. In addition, for the purpose of sensitivity analysis, as well as to estimate effect sizes, all associations were evaluated in binomial logistic models either combining indeterminates with success (i.e. comparing patients with failure versus all others) or with failure (i.e. comparing patients with success versus all others). Barnard's exact test was used to compare proportions. The Brown–Mood median test was used to compare medians. All analyses were performed using JMP software (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

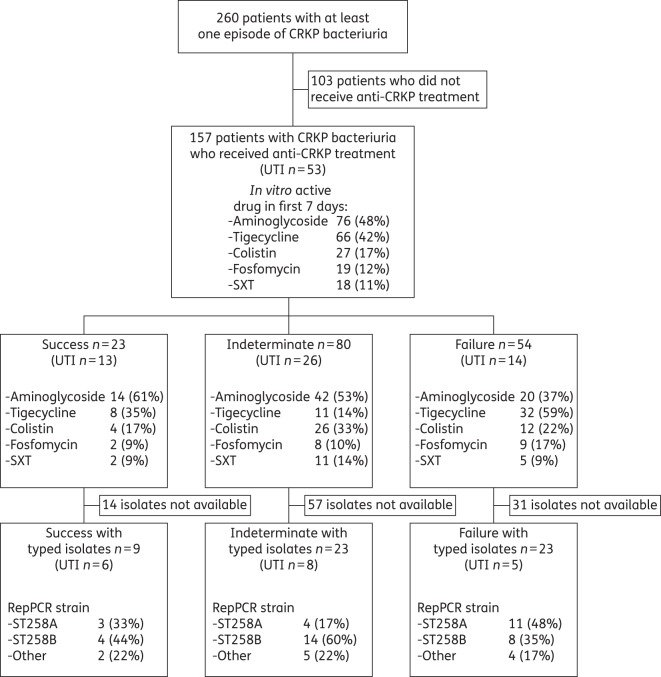

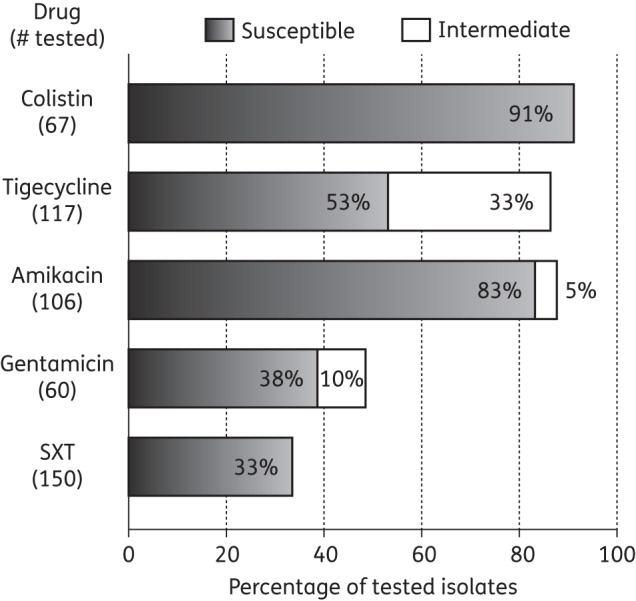

During the 21 month study period, 157 unique patients with physician-diagnosed CRKP UTI were included in the study (Figure 1). Their clinical characteristics are outlined in Table 1. Median follow-up time from date of discharge of the index hospitalization to the end of the study period was 306 days (IQR 193–487 days). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed as clinically indicated (Figure 2). Colistin and amikacin demonstrated the most reliable in vitro activity, with susceptibility rates of 91% and 83% in tested isolates, respectively. Only five isolates were tested against fosfomycin; four of these were resistant.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the treatment of patients in various outcome categories. UTI was as defined in CDC/NHSN criteria. SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes

| All | Success | Indeterminate | Failure | Pa | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 157 | 23 | 80 | 54 | ||

| Female | 93 (59) | 11 (48) | 55 (69) | 27 (50) | 0.4260 | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 72 (61–82) | 73 (58–84) | 74 (63–82) | 71 (59–81) | 0.4231 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.9433 | |||||

| white | 88 (56) | 14 (61) | 44 (55) | 30 (56) | ||

| black | 63 (40) | 8 (35) | 33 (41) | 22 (41) | ||

| Hispanic | 4 (3) | 1 (4) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | ||

| other | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 2 (1–4) | 4 (2–5) | 3.5 (2–6) | 0.1653 | |

| Renal failure upon admissionc | 34 (22) | 3 (13) | 18 (23) | 13 (24) | 0.3771 | |

| UTId | 53 (34) | 13 (57) | 26 (33) | 14 (26) | 0.0210 | 0.0289 |

| Urinary drainage | 0.0783 | 0.3898 | ||||

| physiological | 48 (30) | 8 (35) | 26 (33) | 14 (26) | ||

| Foley catheter | 82 (52) | 9 (39) | 39 (49) | 34 (63) | ||

| other | 27 (17) | 8 (35) | 15 (19) | 6 (11) | ||

| Location at time of culture | 0.0159 | 0.1974 | ||||

| ward | 62 (39) | 10 (43) | 33 (41) | 19 (35) | ||

| emergency department | 61 (39) | 10 (43) | 35 (44) | 16 (30) | ||

| ICU | 34 (22) | 3 (13) | 12 (15) | 19 (34) | ||

| LOS (days), median (IQR) | 11 (7–17) | 13 (10–17) | 10 (6–16) | 9 (6–21) | 0.1393 | |

| Critical illnesse | 39 (25) | 8 (35) | 9 (11) | 22 (41) | 0.0295 | 0.3792 |

| Origin | 0.4438 | |||||

| skilled nursing facility | 86 (55) | 13 (57) | 47 (59) | 26 (48) | ||

| home | 44 (28) | 4 (17) | 22 (28) | 18 (33) | ||

| hospital transfer | 17 (11) | 3 (13) | 7 (9) | 7 (13) | ||

| long-term acute care | 10 (6) | 3 (13) | 4 (5) | 3 (6) | ||

| Disposition | —f | |||||

| skilled nursing facility | 78 (50) | 12 (52) | 45 (56) | 21 (39) | ||

| home | 33 (21) | 5 (22) | 20 (25) | 8 (15) | ||

| long-term acute care | 29 (18) | 6 (26) | 15 (19) | 8 (15) | ||

| death | 16 (10) | — | — | 16 (30) | ||

| hospice | 1 (1) | — | — | 1 (2) |

LOS, length of stay.

All data are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

aP value indicating the univariate relationship between the variable of interest and the ordinal outcome (success, indeterminate, failure).

bMultivariable model including UTI, location, critical illness and urinary drainage.

cRenal failure defined as creatinine >2 mg/dL upon admission.

dUTI as defined by CDC/NHSN.

eCritical illness defined as Pitt bacteraemia score ≥4.

fNot analysed as disposition was part of the outcome definition.

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

UTI as defined by NHSN

Within this cohort of 157 patients with physician-diagnosed CRKP UTI, 53 (34%) met CDC/NHSN criteria for UTI. Of these 53 patients, 10 (19%) had CRKP bacteraemia. In addition, 2 (4%) and 2 (4%) patients had CRKP isolated from wounds and respiratory tract, respectively. Of the 104 patients who did not meet criteria for infection, 14 (13%) had CRKP isolated from non-urinary sources, 8 (8%) from wounds and 3 (3%) from respiratory sources, and 3 (3%) had CRKP bacteraemia >24 h after their urine culture.

Outcomes

In 23 (15%) of 157 patients with physician-diagnosed UTI, treatment success was documented, whereas 54 patients (34%) were deemed treatment failures. The remaining 80 patients (51%) had an indeterminate outcome. Of the 54 patients with treatment failure, 16 (30%) died and 1 (2%) was discharged to a hospice. The remaining 37 (69%) patients had recurrent CRKP bacteriuria. In univariate ordinal regression, CDC/NHSN-defined UTI, location at the time of culture and critical illness were associated with outcome. In a multivariable ordinal model including these variables and urinary drainage, only the association with CDC/NHSN-defined UTI remained significant (P = 0.0289). To determine the direction and magnitude of these associations, we used multivariable binomial models to compare patients with failure versus all others and patients with success versus all others. In the multivariable binomial model comparing patients with failure versus all others, critical illness was associated with failure [adjusted OR (aOR) for failure 2.66, 95% CI 1.09–6.53, P = 0.0313]. None of the other variables was associated with failure. In comparing success versus all others, both CDC/NHSN-defined UTI (aOR for success 2.93, 95% CI 1.13–7.85, P = 0.0273) and critical illness (aOR for success 3.62, 95% CI 1.08–11.98, P = 0.0376) were associated with success. None of the other variables was associated with success.

Treatment

The majority of patients (110/157, 70%) received only one active agent (Table 2). In patients who received a single active agent, aminoglycosides (gentamicin or amikacin) or tigecycline were most commonly used. Forty-seven (30%) patients received more than one active agent, in a variety of combinations (Table 2). Presence of CDC/NHSN-defined UTI was not associated with the use of any specific antimicrobial. CDC/NHSN-defined UTI was also not associated with receipt of more than one active agent; 16/53 (30%) patients with CDC/NHSN-defined UTI received more than one agent compared with 31/104 (30%) patients without CDC/NHSN-defined UTI (not significant). The administration of fosfomycin was associated with absence of critical illness; none of the 39 patients with critical illness received fosfomycin, compared with 19/118 (16%) patients without critical illness (P = 0.004). Critical illness was not associated with receipt of more than one drug or any other treatment choice.

Table 2.

Treatment

| All | Success | Indeterminate | Failure | Pa | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 157 | 23 | 80 | 54 | ||

| Any in vitro active drug in first 7 days | ||||||

| aminoglycoside | 76 (48) | 14 (61) | 42 (53) | 20 (37) | 0.0292 | 0.0041 |

| colistin | 27 (17) | 4 (17) | 11 (14) | 12 (22) | 0.3469 | 0.6531 |

| tigecycline | 66 (42) | 8 (35) | 26 (33) | 32 (59) | 0.0047 | 0.0365 |

| SXT | 18 (11) | 2 (9) | 11 (14) | 5 (9) | 0.7801 | 0.9633 |

| fosfomycin | 19 (12) | 2 (9) | 8 (10) | 9 (17) | 0.2168 | 0.2790 |

| Base of regimenc | 0.0269 | 0.0083 | ||||

| aminoglycoside | 76 (48) | 14 (61) | 42 (53) | 20 (37) | ||

| colistin | 23 (15) | 3 (13) | 10 (13) | 10 (19) | ||

| tigecycline | 36 (23) | 3 (13) | 14 (18) | 19 (35) | ||

| other | 22 (14) | 3 (13) | 14 (18) | 5 (9) | ||

| Single in vitro active drug in first 7 daysd | 110 (70) | 16 (70) | 63 (79) | 31 (57) | 0.0500 | |

| aminoglycoside | 47 (30) | 8 (35) | 28 (35) | 11 (20) | 0.2990 | 0.1004 |

| colistin | 11 (7) | 2 (9) | 8 (10) | 1 (2) | 0.2079 | 0.3182 |

| tigecycline | 30 (19) | 3 (13) | 13 (16) | 14 (26) | 0.0148 | 0.0102 |

| SXT | 14 (9) | 2 (9) | 9 (11) | 3 (6) | 0.6664 | 0.9531 |

| fosfomycin | 8 (5) | 1 (4) | 5 (6) | 2 (4) | 0.9444 | 0.9888 |

| >1 in vitro active drug in first 7 dayse | 47 (30) | 7 (30) | 17 (21) | 23 (43) | 0.0500 | 0.0575 |

| aminoglycoside + tigecycline | 17 (11) | 4 (17) | 9 (11) | 4 (7) | — | |

| aminoglycoside + fosfomycin | 7 (4) | 1 (4) | 3 (4) | 3 (6) | — | |

| aminoglycoside + colistin | 2 (1) | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (2) | — | |

| aminoglycoside + colistin + tigecycline | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | — | |

| aminoglycoside + SXT | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | — | |

| colistin + tigecycline | 11 (7) | 1 (4) | 2 (3) | 8 (15) | — | |

| colistin + fosfomycin | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | — | |

| tigecycline + SXT | 3 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (4) | ||

| tigecycline + fosfomycin | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | 3 (6) | ||

SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

All data are expressed as n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

aP value indicating the univariate relationship between the variable of interest and the ordinal outcome (success, indeterminate, failure).

bAdjusted for the presence of UTI, critical illness and for receipt of more than one anti-CRKP drug (except for single drug variables and single drug versus multiple drugs, which were adjusted for UTI only).

cBase of regimen was assigned as follows: any regimen that contained an aminoglycoside was deemed aminoglycoside-based; any regimen that contained colistin, but not an aminoglycoside, was deemed colistin-based; and any regimen that contained tigecycline, but not colistin or an aminoglycoside, was deemed tigecycline-based. All other regimens were classified as ‘other’.

dComparisons are made within the single drug group.

eThe group of patients who received more than one drug was compared with those who received a single drug. No analyses were performed on individual combination regimens secondary to small numbers.

The association between the use of any single drug and outcomes was evaluated in a multivariable ordinal logistic model that included the drug in question, critical illness, the presence of CDC/NHSN-defined UTI and the use of more than one active antibiotic. In these models, use of aminoglycosides and tigecycline was associated with outcomes. Multivariable binomial models indicated that patients treated with aminoglycosides were less likely to fail therapy (aOR for failure 0.34, 95% CI 0.15–0.73, P = 0.0049), whereas patients treated with tigecycline were more likely to fail therapy (aOR for failure 2.29, 95% CI 1.03–5.13, P = 0.0425). Neither the use of aminoglycosides (aOR for success 2.04, 95% CI 0.80–5.45, P = 0.1362) nor the use of tigecycline (aOR for success 0.59, 95% CI 0.19–1.65, P = 0.3165) was associated with treatment success. To determine whether these associations were influenced by the use of a composite definition for treatment failure, we repeated the models after excluding the 17 patients who did not survive their index hospitalization. The associations between treatment choice and treatment failure remained significant after excluding these patients (data not shown).

We then evaluated the associations between regimen base and outcomes. In multivariable ordinal regression adjusting for critical illness, CDC/NHSN-defined UTI and the use of more than one active antibiotic, regimen base was associated with outcome (P = 0.0083). Further evaluation of this effect with binomial analyses showed an association with failure (P = 0.0065), but not with success (P = 0.4330). Using the aminoglycoside-based regimen group as the reference group, the aORs for failure were 1.92 (95% CI 0.63–5.76) for colistin-based regimens, 5.19 (95% CI 2.03–14.13) for tigecycline-based regimens and 1.71 (95% CI 0.46–5.78) for other regimens.

A non-significant trend was seen towards association between outcome and receipt of more than one active antibiotic in multivariable ordinal regression (P = 0.0575). Patients who received more than one in vitro active agent were more likely to experience failure (aOR for failure 2.53, 95% CI 1.21–5.37, P = 0.0141).

CRKP strains

The isolates of 55 patients were available for strain typing (Table 3). Significant differences were not seen between patients with available index isolates versus those whose isolates were unavailable in demographics, treatment choices or outcomes (data not shown). The predominant strain types were rep-PCR A (n = 18, 33%) and B (n = 26, 47%), both part of the ST258 strain complex.3 The remaining 11 patients had a variety of other strain types identified by rep-PCR. The majority of isolates expressed KPC; 24 (44%) carried blaKPC-2 and 29 (53%) carried blaKPC-3. One isolate carried blaNDM-1 and one was negative for all carbapenemases tested.

Table 3.

Strain types

| All | ST258A | ST258B | Other | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 55 | 18 | 26 | 11 | |

| Female | 27 (49) | 11 (61) | 12 (46) | 4 (36) | 0.1788 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 69 (59–80) | 66 (51–73) | 73 (61–83) | 69 (60–85) | 0.3801 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.4595 | ||||

| white | 35 (64) | 11 (61) | 16 (62) | 8 (73) | |

| black | 17 (31) | 5 (28) | 9 (35) | 3 (27) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (4) | 1 (6) | 1 (4) | 0 | |

| other | 1 (2) | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (1–4) | 4.5 (2–6) | 3 (2–5) | 0.1691 |

| Renal failure upon admissionb | 15 (27) | 4 (22) | 7 (27) | 4 (2–5) | 0.3984 |

| UTIc | 19 (35) | 6 (33) | 8 (31) | 5 (45) | 0.4801 |

| Urinary drainage | 0.6588 | ||||

| physiological | 16 (29) | 4 (22) | 9 (35) | 3 (27) | |

| Foley catheter | 32 (58) | 12 (67) | 15 (58) | 5 (45) | |

| other | 7 (13) | 2 (11) | 2 (8) | 3 (27) | |

| Location at time of culture | 0.7153 | ||||

| ward | 26 (47) | 9 (50) | 10 (38) | 7 (64) | |

| emergency department | 16 (29) | 4 (22) | 11 (42) | 1 (9) | |

| ICU | 13 (24) | 5 (28) | 5 (19) | 3 (27) | |

| LOS (days), median (IQR) | 12 (8–22) | 18 (8–41) | 12 (8–20) | 11 (9–28) | 0.2093 |

| Critical illnessd | 14 (25) | 6 (33) | 5 (19) | 3 (27) | 0.2253 |

| Origin | 0.2989 | ||||

| skilled nursing facility | 21 (38) | 7 (39) | 12 (46) | 2 (20) | |

| home | 20 (36) | 8 (44) | 8 (31) | 4 (36) | |

| hospital transfer | 10 (18) | 3 (17) | 3 (12) | 4 (36) | |

| long-term acute care | 4 (7) | 0 | 3 (12) | 1 (9) | |

| Disposition | 0.8829 | ||||

| skilled nursing facility | 25 (45) | 8 (44) | 13 (50) | 4 (36) | |

| home | 15 (27) | 4 (22) | 8 (31) | 3 (27) | |

| long-term acute care | 8 (15) | 3 (17) | 2 (8) | 3 (27) | |

| death | 7 (13) | 3 (17) | 3 (11) | 1 (9) | |

| Any in vitro active drug in first 7 days | |||||

| aminoglycoside | 26 (47) | 7 (39) | 12 (46) | 7 (64) | 0.2435 |

| colistin | 10 (18) | 5 (28) | 5 (19) | 0 | 0.1788 |

| tigecycline | 21 (38) | 5 (28) | 11 (42) | 5 (45) | 0.1789 |

| SXT | 7 (13) | 1 (6) | 4 (15) | 2 (18) | 0.1789 |

| fosfomycin | 7 (13) | 5 (28) | 1 (4) | 1 (9) | 0.020 |

| >1 in vitro active drug in first 7 days | 15 (27) | 5 (28) | 6 (23) | 4 (36) | 0.5049 |

| Outcome | 0.1073 | ||||

| success | 9 (16) | 3 (17) | 4 (15) | 2 (18) | |

| indeterminate | 23 (42) | 4 (22) | 14 (54) | 5 (45) | |

| failure | 23 (42) | 11 (61) | 8 (31) | 4 (36) |

LOS, length of stay; SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

All data are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

aComparing rep-PCR A versus all others.

bRenal failure defined as creatinine >2 mg/dL upon admission.

cUTI as defined by CDC/NHSN.

dCritical illness defined as Pitt bacteraemia score ≥4.

None of the clinical variables was significantly associated with ST258A, except for fosfomycin use, which was more common in patients with ST258A (P = 0.0317). On univariate ordinal regression, strain type was not associated with outcome. We then constructed a multivariable ordinal regression model (Table 4) that included strain type and the variables previously identified as related to outcome (CDC/NHSN-defined UTI, tigecycline use and aminoglycoside use). In this model, ST258A was associated with outcome (P = 0.0343). In binomial models, ST258A was associated with failure (aOR for failure 5.82, 95% CI 1.47–28.50, P = 0.0113), but not associated with success (aOR for success 0.73, 95% CI 0.12–3.74, P = 0.7120). We also constructed a model that included the base of the regimen used (Table 5). In this model a trend towards association was seen for ST258A and outcome (P = 0.0598). In the corresponding binomial models, ST258A was again associated with failure (aOR for failure 5.07, 95% CI 1.32–23.59, P = 0.0176), but not associated with success (aOR for success 0.89, 95% CI 0.14–4.62, P = 0.8935). To determine whether the increased failure rates of patients infected with ST258A were related to the increased use of fosfomycin, we repeated these models after exclusion of patients treated with fosfomycin. The association between strain type and treatment failure remained significant after excluding these patients (data not shown). Furthermore, we evaluated whether these results were influenced by the use of a composite outcome by repeating the analyses excluding those patients who did not survive their index hospitalization (n = 7). Excluding these patients also did not alter the association between strain type and treatment failure (data not shown).

Table 4.

Strain type analysis adjusted for treatment regimen

| Pa | aOR for successb | Pb | aOR for failurec | Pc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST258A versus other | 0.0343 | 0.73 (0.12–3.74) | 0.7120 | 5.82 (1.47–28.50) | 0.0113 |

| UTId | 0.0575 | 4.32 (0.94–24.03) | 0.0607 | 0.41 (0.10–1.50) | 0.1807 |

| Tigecycline | 0.0094 | 0.15 (0.01–1.11) | 0.0645 | 5.83 (1.46–28.52) | 0.0116 |

| Aminoglycoside | 0.8147 | 0.54 (0.10–2.70) | 0.4512 | 1.05 (0.29–4.05) | 0.9413 |

The model includes the following variables: UTI, tigecycline, aminoglycoside and strain A versus all other.

aOrdinal logistic regression.

bBinomial logistic regression success versus all others.

cBinomial logistic regression failure versus all others.

dUTI as defined by CDC/NHSN.

Table 5.

Strain type analysis adjusted for treatment regimen base

| Pa | aOR for successb | Pb | aOR for failurec | Pc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST258A versus other | 0.0598 | 0.89 (0.14–4.62) | 0.8935 | 5.07 (1.32–23.59) | 0.0176 |

| UTId | 0.0169 | 5.23 (1.17–28.59) | 0.0302 | 0.28 (0.06–1.05) | 0.0587 |

| Regimen base | 0.1495 | 0.7233 | 0.1052 | ||

| aminoglycoside (reference) | — | — | |||

| colistin | 1.74 (0.19–13.35) | 0.96 (0.16–5.31) | |||

| tigecycline | 0.47 (0.02–4.18) | 5.08 (1.07–29.31) | |||

| other | 1.85 (0.20–14.14) | 0.41 (0.04–2.84) |

The model includes the following variables: presence of UTI, regimen base and strain A versus all other.

aOrdinal logistic regression.

bBinomial logistic regression success versus all others.

cBinomial logistic regression failure versus all others.

dUTI as defined by CDC/NHSN.

Discussion

This study shows that the outcomes of CRKP UTI are influenced by both the choice of antimicrobial treatment and the CRKP strain type. In this large prospective multicentre cohort, patients who were treated with aminoglycosides enjoyed better outcomes, whereas patients treated with tigecycline experienced worse outcomes. These associations remained significant after adjustment for relevant clinical co-variables. In addition, we report here the first evidence that patients infected with the CRKP strain ST258A are more likely to have treatment failure. The ST258 strain complex is the most common strain complex of CRKP globally, and was recently shown to consist of at least two clinically and molecularly distinct strain types.3,5,12,13 The current finding that ST258A is associated with worse outcomes after treated CRKP bacteriuria adds to this growing knowledge base, and emphasizes the link between clinical and molecular findings. The molecular mechanisms causing these observed clinical differences between patients with different CRKP strains remain unclear. Different strains may carry different virulence factors encoded in chromosomal or plasmid DNA. In support of this, ST258 CRKP was shown to be more virulent compared with other CRKP strains in a Caenorhabditis elegans model, whereas blaKPC-2 was not itself associated with virulence.14 Candidates for virulence factors that may differ between various strains include changes in types of capsular polysaccharides (variations in the cps locus) or the mere overproduction of these polysaccharides, expression of iron chelators, mutations in porins such as OmpK35 and OmpK36 and other changes.15–17

The treatment of CRKP infections is challenging and, while new antibiotic options are on the horizon, unfortunately these will require time before they become widely available. In the meantime, most data on the treatment of CRKP infections have been reported from patients with CRKP bloodstream infections, and only limited data exist for other CRKP infections.18–21 Qureshi et al.22 recently reported their retrospective experience in a cohort of 21 patients with UTI. Interestingly, use of doxycycline for these infections was common at their centre and resulted in clinical cure in all nine patients treated in this way. In our cohort, doxycycline was not a common treatment choice and was not included in analyses. We noted that treatment with aminoglycosides appeared to be associated with better outcomes. This is consistent with data from Satlin et al.,23 who reported superior urinary clearance with aminoglycoside therapy. In another study that described a retrospective cohort that included seven patients who were treated with aminoglycosides, the same trend towards increased efficacy of aminoglycosides was observed.24 In contrast, tigecycline—which is primarily excreted through faeces and does not achieve high urinary levels25—was associated with worse outcomes in our cohort. In addition to this link to poor clinical outcomes, we have recently reported that the use of tigecycline in these patients is associated with the subsequent rapid development of tigecycline resistance.26

Our study has several important limitations. First, the study of UTIs is problematic as a universally accepted gold standard does not exist. The distinction between colonization and infection is quite difficult, especially in older patients with urinary catheters. Therefore, we chose to study all patients in whom the treating clinician deemed directed therapy was necessary, rather than relying solely on criteria developed for the purpose of surveillance. As expected, only a subset of patients who were treated met criteria for UTI by CDC/NHSN guidelines. The disadvantage of this approach is that patients with urinary CRKP colonization may been included in whom antibiotic treatment was unlikely to be of any clinical benefit. In all analyses, we have adjusted for presence of UTI by CDC/NHSN criteria. A second limitation is that this was an observational study in which treating physicians were free to treat who they wanted and use whichever regimen they deemed appropriate. Confounding by indication will occur in this situation. As an example of this, we noted that receipt of more than one active agent was associated with an increased likelihood of failure. Another consequence is that the treatment regimens were quite heterogeneous and difficult to analyse. Interventional studies will be needed to determine the best approach to CRKP UTI. A third limitation involves the difficulty of assigning a definitive outcome to all patients. For about half of the patients, the outcome was deemed indeterminate. To address this issue, we performed not only ordinal analyses, but also binomial analyses in both directions. In this way, we provided a sensitivity analysis by grouping the patients either with an indeterminate outcome with patients who failed, or with patients with a successful outcome. Furthermore, we repeated the models after exclusion of those patients who did not survive their index hospitalization and found very similar results.

In summary, we found, in concordance with previously published data, that aminoglycosides appear to be associated with the best clinical outcomes in patients treated for CRKP bacteriuria. This may inform the future design of the control arm in studies on treatment of CRKP UTI with newer agents with activity against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. In addition, we report preliminary data linking the molecularly and clinically distinct CRKP clade ST258A to worse clinical outcomes in CRKP bacteriuria. This finding will need to be validated in other independent studies to further our understanding of outcomes in K. pneumoniae strains.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UM1AI104681, and by funding to D. v. D. and F. P. from the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. V. G. F. was supported by Mid-Career Mentoring Award K24-AI093969 from NIH. In addition, this work was supported in part by the Veterans Affairs Merit Review Program (R. A. B.), the National Institutes of Health (Grant AI072219-05 and AI063517-07 to R. A. B.), and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center VISN 10 (R. A. B.), the Research Program Committees of the Cleveland Clinic (D. v. D.) and an unrestricted research grant from the STERIS Corporation (D. v. D.).

Transparency declarations

D. v. D. has received research funding from Steris Inc. and has served on the Speaker's Bureau for Astellas, on a drug safety monitoring board for Pfizer and on a consultancy board for Sanofi Pasteur. R. A. B. has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Merck and Checkpoints, and has served on a Tetraphase drug safety monitoring board. All other authors: none to declare.

Disclaimer

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the patients described in this paper and their families.

References

- 1.Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1791–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Duin D, Kaye KS, Neuner EA, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a review of treatment and outcomes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;75:115–20. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Duin D, Perez F, Rudin SD, et al. Surveillance of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: tracking molecular epidemiology and outcomes through a regional network. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4035–41. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02636-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasheed JK, Kitchel B, Zhu W, et al. New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:870–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1906.121515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deleo FR, Chen L, Porcella SF, et al. Molecular dissection of the evolution of carbapenem-resistant multilocus sequence type 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:4988–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321364111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC. CDC/NHSN Surveillance Definitions for Specific Types of Infections. http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/17pscnosinfdef_current.pdf . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Chow JW, Yu VL. Combination antibiotic therapy versus monotherapy for gram-negative bacteraemia: a commentary. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;11:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(98)00060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-second Informational Supplement M100-S22. Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lascols C, Hackel M, Marshall SH, et al. Increasing prevalence and dissemination of NDM-1 metallo-β-lactamase in India: data from the SMART study (2009) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1992–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viau RA, Hujer AM, Marshall SH, et al. “Silent” dissemination of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates bearing K. pneumoniae carbapenemase in a long-term care facility for children and young adults in Northeast Ohio. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1314–21. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4178–82. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4178-4182.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramirez MS, Xie G, Marshall SH, et al. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates: a zone of high heterogeneity (HHZ) as a tool for epidemiological studies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:E254–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright MS, Perez F, Brinkac L, et al. Population structure of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from midwestern U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4961–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00125-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavigne JP, Cuzon G, Combescure C, et al. Virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates harboring bla KPC-2 carbapenemase gene in a Caenorhabditis elegans model. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diago-Navarro E, Chen L, Passet V, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae exhibit variability in capsular polysaccharide and capsule associated virulence traits. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:803–13. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robin F, Hennequin C, Gniadkowski M, et al. Virulence factors and TEM-type β-lactamases produced by two isolates of an epidemic Klebsiella pneumoniae strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1101–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05079-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai YK, Fung CP, Lin JC, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae outer membrane porins OmpK35 and OmpK36 play roles in both antimicrobial resistance and virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1485–93. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01275-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tumbarello M, Viale P, Viscoli C, et al. Predictors of mortality in bloodstream infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae: importance of combination therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:943–50. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zarkotou O, Pournaras S, Tselioti P, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with bloodstream infections caused by KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and impact of appropriate antimicrobial treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1798–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qureshi ZA, Paterson DL, Potoski BA, et al. Treatment outcome of bacteremia due to KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: superiority of combination antimicrobial regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2108–13. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06268-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daikos GL, Tsaousi S, Tzouvelekis LS, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections: lowering mortality by antibiotic combination schemes and the role of carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:2322–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02166-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qureshi ZA, Syed A, Clarke LG, et al. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of patients with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteriuria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3100–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02445-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satlin MJ, Kubin CJ, Blumenthal JS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of aminoglycosides, polymyxin B, and tigecycline for clearance of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from urine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5893–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00387-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander BT, Marschall J, Tibbetts RJ, et al. Treatment and clinical outcomes of urinary tract infections caused by KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a retrospective cohort. Clin Ther. 2012;34:1314–23. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann M, DeMaio W, Jordan RA, et al. Metabolism, excretion, and pharmacokinetics of [14C]tigecycline, a first-in-class glycylcycline antibiotic, after intravenous infusion to healthy male subjects. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:1543–53. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.015735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Duin D, Cober E, Richter S, et al. Tigecycline therapy for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) bacteriuria leads to tigecycline resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12714. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]