Abstract

Social networking sites (SNSs) can be beneficial tools for users to gain social capital. Although social capital consists of emotional and informational resources accumulated through interactions with strong or weak social network ties, the existing literature largely ignores attachment style in this context. This study employed attachment theory to explore individuals' attachment orientations toward Facebook usage and toward online and offline social capital. A university student sample (study 1) and a representative national sample (study 2) showed consistent results. Secure attachment was positively associated with online bonding and bridging capital and offline bridging capital. Additionally, secure attachment had an indirect effect on all capital through Facebook time. Avoidant attachment was negatively associated with online bonding capital. Anxious–ambivalent attachment had a direct association with online bonding capital and an indirect effect on all capital through Facebook. Interaction frequency with good friends on Facebook positively predicted all online and offline capital, whereas interaction frequency with average friends on Facebook positively predicted online bridging capital. Interaction frequency with acquaintances on Facebook was negatively associated with offline bonding capital. The study concludes that attachment style is a significant factor in guiding social orientation toward Facebook connections with different ties and influences online social capital. The study extends attachment theory among university students to a national sample to provide more generalizable evidence for the current literature. Additionally, this study extends attachment theory to the SNS setting with a nuanced examination of types of Facebook friends after controlling extraversion. Implications for future research are discussed.

Introduction

Social networking sites (SNSs) have been positioned as beneficial tools for users to gain social capital in the existing literature on university students,1 international students,2 and national populations.3 Research has shown that extraversion1,2 is an important predictor of social capital. Social capital consists of emotional and informational resources accumulated through interactions with strong or weak ties,4,5 but existing studies largely ignore individuals' innate need for social connectedness with others, and attachment style, when studying the effects of SNSs on social relationships.6

Based on attachment theory,7,8 attachment style is formed from repeated interactions between an infant and the main caregiver. These interactions eventually develop an internal working model for infants that guides their behavior with their caregivers. The model allows infants to feel secure and to defend themselves against separation or loss.9 An infant develops a secure attachment style when the main caregiver responds in a timely and consistent way to the baby's needs.10,11 Conversely, if the main caregiver consistently rejects the infant's requests for physical interaction or ignores the infant's needs, the baby will learn to avoid the caregiver, developing an avoidant orientation.12 Alternatively, if the main caregiver provides inconsistent responses or consistently interferes with the infant's activity, the baby will protest by crying more and will gradually form an anxious–ambivalent approach toward the caregiver.13

These attachment orientations play an important role in individuals' initiation, formation, and maintenance of social relationships with others.14–17 Studies have shown that individuals with secure attachments are comfortable with distance from others and are willing to depend on others and to let others depend on them. Contrarily, individuals with an avoidant attachment will show nervous reactions when others are too close to them. Individuals with anxious–ambivalent attachment constantly worry about others leaving them and thus frequently desire closer relationships. These patterns have been repeatedly found in offline friendships and romantic relationships.15,17,18

Recently, a small number of studies have explored the role of attachment style in online settings, including its effect on online friendships,19 online information dissemination,6 and Facebook use.20,21 These studies suggest that attachment style predicts online social interaction in the same way that it does in the offline context.6 As an environment in which individuals can initiate and manage online and offline social connections, Facebook serves attachment functions and allows users to approach it with different attachment styles.21 For example, securely attached individuals are the best situated to become social hubs, exhibiting larger networks and the most social ties with others.6 Individuals with high attachment anxiety have more frequent Facebook use and are constantly concerned about how others perceive them on Facebook. High attachment avoidance is associated with less Facebook use and less interest in Facebook.21 The evidence supports predictions from attachment theory regarding general Facebook use and online social network structure.

Most studies have focused on validating patterns of attachment styles in online environments and in Facebook use, but very limited attention22 has been paid to the social capital accumulated through Facebook use. Social capital has been found to be an important outcome of social interactions through Facebook usage1–3 and is strongly related to the way individuals interact with social ties of various strengths. Bonding social capital is formed when individuals reciprocally provide and receive emotional support and limited resources that require mutual trust, such as putting their reputation on the line for close friends and family.23 Bridging social capital involves individuals mobilizing resources via different networks and broadening their network through interactions with weak or bridging ties,4,24 such as acquaintances or online-only friends. Individual attachment style thus influences the formation of these types of social capital because individuals' orientation toward social relationships is closely connected to their social resources and ties. Indeed, secure attachment has been found to predict online bonding and bridging capital positively, whereas avoidant attachment is negatively associated with both types of online social capital.22 In addition to the direct associations, the current study considers the frequency of Facebook interaction with different types of ties that help to form social capital in an effort to examine the nuances of the three types of attachment styles and social capital. Existing research has established the essential role of extraversion in forming social capital1,2; thus, extraversion was controlled in this study.

H1a: Attachment style influences online social capital after controlling for extraversion. Secure and anxious–ambivalent attachment has positive associations with online social capital, and avoidant attachment has a negative association with online social capital.

H1b: The frequency of interaction with different ties on Facebook influences online social capital, controlling for extraversion and attachment style. Interacting with strong ties on Facebook has a positive association with online capital. Interacting with weak ties has positive associations with online bridging capital.

This study also examines the association of attachment style and Facebook interaction frequency with offline social capital. Online Facebook networks overlap with offline networks.25 Managing online networks via Facebook interaction may simultaneously strengthen offline social capital.26 Current evidence has not shown a consistent association between Facebook use and offline social capital.2,3 This study explores the effect of attachment style on offline social capital to shed light on the current literature.

H2a: Attachment style influences offline social capital, controlling for extraversion in the same direction as H1a.

H2b: The frequency of interacting with different ties on Facebook influences offline social capital, controlling for extraversion and attachment style in the same direction as H2a.

The current literature indicates that different attachment styles have different approaches to the use of Facebook.6,21 Additionally, abundant evidence has shown that Facebook use results in greater levels of perceived social capital.27 This study explores the mediating role of Facebook use in the effects of attachment style on online and offline social capital.

H3: Attachment style influences online and offline social capital through Facebook use. Secure attachment and ambivalent attachment positively influence online and offline capital through Facebook use, whereas avoidant attachment does not.

Existing research has explored attachment style in online contexts among university students. In addition to university students (study 1), this study employs a nationally representative sample (study 2) for more generalizability.

Study 1

Procedure and participants

An online survey was conducted at four large universities in the northern and southern parts of Taiwan. Recruitment e-mails, posters, and course promotions were employed to promote the annual survey. This survey was part of the SNS topic in the Digital Media Audiences Annual Project, which comprises seven topics with a limited number of questions per topic. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the seven topics. Data collection lasted for 1 month.

Of the 890 participants, 371 (41.7%) were male, and 77.5% were undergraduate students. The average age of the participants was 22.62 years old (SD=2.33; range 18–30 years).

Measurement

Attachment style

Attachment style was measured using need for connectedness statements.15 This method was chosen to follow previous scholars' methods of measuring this construct and has been validated in existing research.28 Participants rated statements on a 7-point scale, where 1=“completely disagree” and 7=“completely agree.” Statements included “I am comfortable depending on others” (secure), “I am nervous when anyone gets too close” (avoidant), and “I often worry that my partner won't stay with me” (anxious–ambivalent).

Online and offline social capital

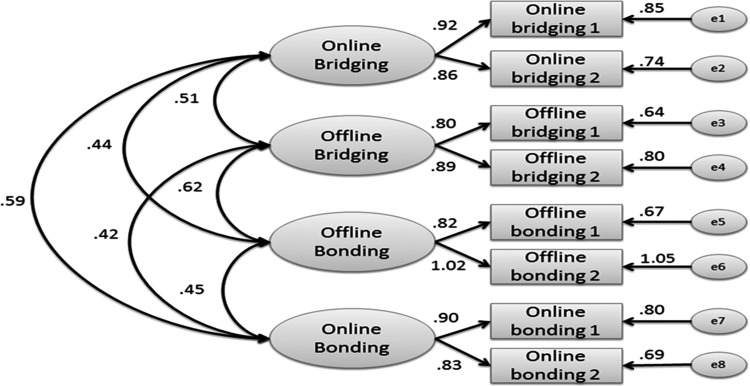

Table 1 shows the scale items, selection description, and reliability scores of each scale. A confirmatory factor analysis (Fig. 1) using the current data in AMOS v20 and the average variance extracted analysis (Table 2) further showed that each scale had excellent convergent and discriminant validity.30

Table 1.

Measurements of Online and Offline Social Capital in Study 1 and Study 2

| Study 1 (college sample) |

| Bridging capital (outward looking dimension, online: α=0.89; offline: α=0.84) |

| Interacting with people on Facebook/offline makes me interested in things that happen outside of my town. |

| Interacting with people on Facebook/offline makes me want to try new things. |

| Bonding capital (emotional support dimension, online: α=0.86; offline: α=0.92) |

| There are several people on Facebook/offline I trust to help solve my problems. |

| There is someone on Facebook/offline I can turn to for advice about making very important decisions. |

| Study 2 (national sample) |

| Bridging social capital (online: α=0.80; offline: α=0.84) |

| Talking with people online/offline makes me curious about other places in the world. (“outward looking” dimension) |

| Interacting with people online/offline makes me feel connected to the bigger picture. (“view of oneself as part of a broader group” dimension) |

| Bonding social capital (online: α=0.80; offline: α=0.80) |

| The people I interact with on Facebook/offline would put their reputations on the line for me. (“access to limited resources” dimension) |

| The people I interact with on Facebook /offline would help me fight an injustice. (“mobilized solidarity” dimension) |

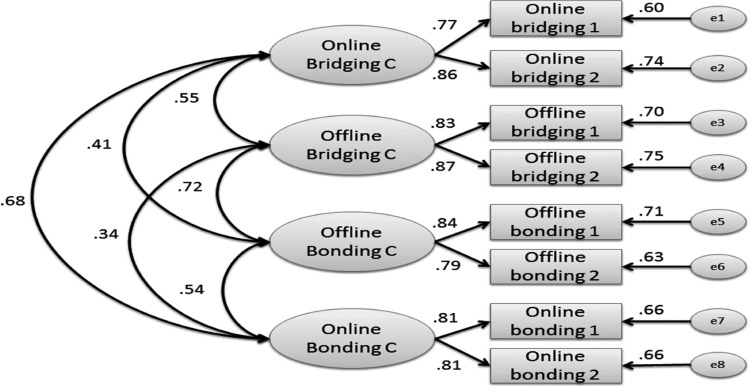

In study 1, the central dimensions of “emotional support” and “outward looking” subscales29 were chosen for bonding and bridging capital. These items had the greatest factor loading in Williams' findings.29 The reason for employing only two items in each dimension was because the question cap was limited by the annual survey. Nevertheless, the confirmatory factor analysis (Fig. 1) for the concepts showed good fit to the data and good reliability and validity between these dimensions. In study 2, the complete scale from Williams29 was pretested. Only two items from each dimension of online and offline social capital were allowed. Therefore, the team conducted an exploratory factor analysis and chose the two items with the highest loadings in both online and offline settings. CFA (Fig. 2) was employed in this study to confirm the factors further. Study 1 and study 2 each examined the sub-dimensions of the complete scales in Williams.29 The similar pattern of the results found in both studies further nuances the findings.

FIG. 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis of online and offline social capital scales in study 1. Note. The model has a chi square of 92.33 (p=0.00), normed fit index (NFI)=0.98, comparative fit index (CFI)=0.98, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)=0.079 (p=0.001). N=890. Chi square tends to be always significant in samples with more than 400 participants and is not a proper indicator in large samples. Therefore, taking references from other indicators, this model has a reasonable fit to the data (RMSEA <0.08).

Table 2.

Analyses of Reliability, and Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Study 1 Social Capital Subscales

| CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | Off bridge | On bridge | Off bond | On bond | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Off bridge | 0.836 | 0.719 | 0.386 | 0.275 | 0.848 | |||

| On bridge | 0.884 | 0.793 | 0.350 | 0.269 | 0.514 | 0.891 | ||

| Off bond | 0.923 | 0.858 | 0.386 | 0.261 | 0.621 | 0.440 | 0.926 | |

| On bond | 0.856 | 0.749 | 0.350 | 0.243 | 0.418 | 0.592 | 0.450 | 0.866 |

According to Hair et al.,30 CR should be >0.70 for good reliability, AVE >0.50 indicates great convergent validity, and MSV <AVE and ASV <AVE both indicate great discriminant validity. The analysis showed that all social capital scales in study 1 have excellent reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity. The numbers in the right section show the correlation scores.

CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted; MSV, maximum shared variance; ASV, average shared variance.

Frequency of interaction with different Facebook friends

Participants indicated their frequency of interacting with family, good friends, average friends, acquaintances, and online-only connections using an 8-point scale, where 1=“never,” 2=“very infrequently,” and 8=“very frequently.” The categorization of friendship was adopted from Manago et al.31 In addition to family, good friends represent close friends who provide emotional support and advice on important decisions. Average friends include connections with whom one can have casual conversations and interactions. In Chinese, acquaintances indicate connections with whom one would only nod to say hello, and online-only friends indicate connections with whom one interacts only online.

Facebook time

Time spent on Facebook was measured by asking participants how many days they used Facebook in a week followed by asking them to estimate the average time they spent per day of use. The total time in a week was derived by multiplying days by minutes per day.

Extraversion

Extraversion (α=0.78) was measured by three statements32—“I am outgoing,” “I am sociable,” and “I have an assertive personality”—on a 7-point scale, where 1=“completely disagree” and 7=“completely agree.”

Results

For H1a and H1b, hierarchical linear regressions (Table 3) conducted in SPSS v20, with extraversion entered in the first step, attachment style in the second step, and frequency of interacting with types of Facebook friends in the third step, showed that a secure attachment style was a positive predictor of online bonding and bridging social capital. An avoidant attachment style negatively predicted online bonding capital, whereas an ambivalent attachment positively predicted online bonding capital. Interaction frequency with good friends on Facebook positively predicted both types of online capital, and the frequency of interaction with average friends positively predicted online bridging capital.

Table 3.

Standardized Regression Coefficients of Hierarchical Linear Regressions

| Collinearity test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online bridge | Online bond | Offline bridge | Offline bond | Tolerance | VIF | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.257*** | 0.243*** | 0.262*** | 0.234*** | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.272*** | 0.217*** | 0.259*** | 0.224*** | 0.889 | 1.125 |

| Secure | 0.114*** | 0.177*** | 0.091** | 0.066 | 0.886 | 1.129 |

| Avoidant | 0.054 | −0.072* | 0.021 | −0.013 | 0.826 | 1.211 |

| Anxious–ambivalent | 0.057 | 0.076* | −0.011 | −0.005 | 0.803 | 1.246 |

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.130*** | 0.087** | 0.194*** | 0.150*** | 0.784 | 1.275 |

| Secure | 0.085** | 0.150*** | 0.077* | 0.052 | 0.881 | 1.135 |

| Avoidant | 0.043 | −0.086** | 0.006 | −0.029 | 0.817 | 1.224 |

| Anxious–ambivalent | 0.012 | 0.033 | −0.033 | −0.022 | 0.789 | 1.268 |

| FB interaction: family | 0.005 | −0.005 | −0.009 | 0.041 | 0.926 | 1.080 |

| FB interaction: good friends | 0.315*** | 0.365*** | 0.287*** | 0.288*** | 0.670 | 1.493 |

| FB interaction: average friends | 0.140*** | 0.058 | −0.057 | 0.026 | 0.523 | 1.913 |

| FB interaction: acquaintance | 0.018 | 0.020 | −0.011 | 0.120** | 0.583 | 1.714 |

| FB interaction: online-only friends | 0.003 | −0.006 | 0.017 | −0.024 | 0.785 | 1.274 |

| R2 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.14 | ||

p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<.001.

VIF, variance inflation factor; FB, Facebook.

For offline social capital (H2a and H2b), the same steps entered in the hierarchical linear regressions shown in Table 3 showed that secure attachment style predicted offline bridging social capital. Interaction frequency with good friends on Facebook positively predicted both types of offline capital. Furthermore, interaction frequency with acquaintances on Facebook negatively predicted offline bonding social capital.

Regarding the indirect effect of attachment style on social capital through Facebook time (H3), a series of mediation analyses employing bootstrap methods using the macro “PROCESS”33,34 in SPSS v20 (Table 4) indicated that secure and anxious–ambivalent attachment orientations had positive indirect effects on both online and offline bonding and bridging social capital through Facebook use time. The avoidant attachment style did not have an indirect effect on social capital through Facebook time.

Table 4.

Statistics of Indirect Effects from the Bootstrapping Analyses (Study 1)

| Effect size | Bootstrapped SE | Bootstrapped CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Secure→FB time→Online bridging social capital | |||

| 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.0002–0.03* | |

| 2. Secure→FB time→Online bonding social capital | |||

| 0.013 | 0.007 | 0.0002–0.03* | |

| 3. Secure→FB time→Offline bridging social capital | |||

| 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.001–0.013* | |

| 4. Secure→FB time→Offline bonding social capital | |||

| 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.001–0.014* | |

| 5. Avoidant→FB time→Online bridging social capital | |||

| 0.010 | 0.008 | −0.004–0.03 | |

| 6. Avoidant→FB time→Online bonding social capital | |||

| 0.010 | 0.008 | −0.003–0.03 | |

| 7. Avoidant→FB time→Offline bridging social capital | |||

| 0.004 | 0.004 | −0.001–0.013 | |

| 8. Avoidant→FB time→Offline bonding social capital | |||

| 0.004 | 0.004 | −0.001–0.013 | |

| 9. Anxious→FB time→Online bridging social capital | |||

| 0.031 | 0.008 | 0.015–0.048* | |

| 10. Anxious→FB time→Online bonding social capital | |||

| 0.03 | 0.009 | 0.015–0.049* | |

| 11. Anxious→FB time→Offline bridging social capital | |||

| 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.004–0.026* | |

| 12. Anxious→FB time→Offline bonding social capital | |||

| 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.004–0.026* | |

Note. *indicates statistically significant.

SE, standardized error; CI, confidence interval.

Study 2

Procedure and participants

Among 2,000 representative participants aged ≥20 years in the Taiwan Communication Survey (TCS) conducted in 2013, 1,109 used Facebook the most and thus served as the sample for this analysis. The survey was conducted face-to-face assisted by a tablet on which the interviewers could immediately enter data into the system. All distributions of demographics in this national sample matched those of the national census population. More details can be found on the Web site.35 Among the 1,109 Facebook users, the average age was 35.73 years (range 20–99 years), 47.7% were male, and users spent an average of 713.52 minutes per week on Facebook (range 2.5-6720 min/week, SD=956.67).

Measure

The national survey35 consists of basic media questions and seven subtopics that have limited questions and that did not include full scales for concepts in this survey. Therefore, only secure and avoidant attachment styles were included in this survey. These styles were measured as in study 1 because secure and avoidant styles represent two opposite anchors of orientation for social connections.

For social capital, two items with the highest loadings from the exploratory factor analysis29 were suggested from a pilot test for the bonding dimension, and two were suggested for the bridging dimension conducted by the design team (Table 1). Additionally, a confirmatory factor analysis (Fig. 2) using the national data in AMOS v20 and the average variance extracted analysis showed that each scale had good reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity (Table 5).30 All the other variables were the same as those in study 1.

FIG. 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis of online and offline social capital scales in study 2. Note. The model has a chi square of 96.41 (p=0.00), NFI=0.98, CFI=0.988, RMSEA=0.067 (p=0.01). Chi square tend to be always significant in samples with more than 400 participants and is not a proper indicator in large samples. Therefore, taking references from other indicators, this model has a close fit to the data.

Table 5.

Analyses of Reliability, and Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Social Capital Subscales in Study 2

| CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | Off bridge | On bridge | Off bond | On bond | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Off bridge | 0.839 | 0.723 | 0.514 | 0.312 | 0.850 | |||

| On bridge | 0.802 | 0.670 | 0.456 | 0.312 | 0.554 | 0.819 | ||

| Off bond | 0.801 | 0.668 | 0.514 | 0.326 | 0.717 | 0.415 | 0.817 | |

| On bond | 0.795 | 0.659 | 0.456 | 0.287 | 0.339 | 0.675 | 0.540 | 0.812 |

According to Hair et al.,30 CR should be >0.70 for good reliability, AVE >0.50 indicates great convergent validity, and MSV <AVE and ASV <AVE both indicate great discriminant validity. The analysis showed that all social capital scales in study 2 have excellent reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity. The numbers in the right section show the correlation scores.

Results

The national survey does not include questions about interaction frequency with different types of friends on Facebook. Based on the available items in the national survey, hierarchical regression models conducted in SPSS v20 with extraversion entered in the first step, attachment styles in the second step, and Facebook time in the third step (Table 6) showed that a secure attachment style positively predicted both online bonding and bridging capital (H1a) but not offline capital (H2a). An avoidant attachment did not predict online or offline capital. Facebook time of use positively predicted online bonding and bridging social capital.

Table 6.

Standardized Regression Coefficients of Hierarchical Linear Regressions

| Collinearity test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Online bridge | Online bond | Offline bridge | Offline bond | Tolerance | VIF |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.238*** | 0.201*** | 0.227*** | 0.251*** | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.226*** | 0.187*** | 0.222*** | 0.244*** | 0.975 | 1.026 |

| Secure attach | 0.088** | 0.089** | 0.032 | 0.043 | 0.921 | 1.085 |

| Avoidant attach | 0.045 | −0.008 | −0.001 | −0.047 | 0.941 | 1.063 |

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.218*** | 0.179*** | 0.221*** | 0.243*** | 0.961 | 1.041 |

| Secure attach | 0.081** | 0.082** | 0.031 | 0.043 | 0.914 | 1.094 |

| Avoidant attach | 0.048 | −0.005 | 0.000 | −0.047 | 0.939 | 1.064 |

| FB time | 0.069* | 0.073* | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.974 | 1.027 |

| R2 (SE) | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | ||

p<0.005; **p<0.01; *p<0.05.

Employing the same bootstrapping method as in study 1, a series of analyses for indirect effects (Table 7) showed that secure attachment had an indirect effect on online bonding and bridging social capital through Facebook. Avoidant attachment did not have an indirect effect on any social capital through Facebook.

Table 7.

Statistics of Indirect Effects from the Bootstrapping Analyses (Study 2)

| Effect size | Boot SE | Bootstrapped CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13. Secure→FB time→Online bridging social capital | |||

| 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.003–0.013* | |

| 14. Secure→FB time→Online bonding social capital | |||

| 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.003–0.015* | |

| 15. Secure→FB time→Offline bridging social capital | |||

| 0.003 | 0.002 | −0.001–0.008 | |

| 16. Secure→FB time→Offline bonding social capital | |||

| 0.003 | 0.002 | −0.001–0.008 | |

| 17. Avoidant→FB time→Online bridging social capital | |||

| −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.008–0.003 | |

| 18. Avoidant→FB time→Online bonding social capital | |||

| −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.005–0.001 | |

| 19. Avoidant→FB time→Offline bridging social capital | |||

| −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.004–0.001 | |

| 20. Avoidant→FB time→Offline bonding social capital | |||

| −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.004–0.001 | |

Note. * indicates statistically significant.

Discussion

Study 1 among university students and study 2 using nationally representative data both showed that attachment is a significant consideration in research regarding SNSs and social capital. These studies also showed that, controlling for the important personality trait of extraversion,1,2,20 attachment style guides individuals' social orientations toward other people and thus influences their different approaches to Facebook. Consistent with theory and the previous literature,19 a secure attachment style is the best-situated social hub.6 Both samples in this study showed that secure attachment received greater levels of online bonding capital, including emotional support and access to limited resources, and online bridging capital, including outward looking and a sense of being part of a broader group. This finding resonates with the rich-get-richer hypothesis in the HomeNet studies,36,37 indicating that those who already have advantages in social relationships gain greater social capital through comfortable social interactions on Facebook. In addition to online capital, the results of the university sample showed that secure attachment style was positively associated with offline social bridging capital (outward looking). The mediation analyses further showed that individuals with secure attachment orientation accumulate more online (study 1 and study 2) social capital through greater Facebook use. Study 1 also showed that Facebook time could help securely attached individuals obtain more offline social capital. This finding may be due to the large, overlapping online and offline networks among university students. The results also showed that managing offline networks online could mobilize online resources to offline networks.

In contrast, avoidant attachment was negatively associated with online bonding capital (study 1). People with avoidant orientations essentially avoid social interaction,21 especially for emotional support with strong ties. This tendency leads to the perception in previous literature that these individuals do not have online or offline social resources for reciprocal favors that require mutual trust.12 At the same time, Facebook does not facilitate the process of accumulating reciprocal social resources. As the results indicate, avoidant attachment does not lead to online or offline social capital through Facebook use. This finding supports the poor-get-poorer hypothesis,36,37 in which those who have disadvantages in real life receive less support through Facebook. It is possible that individuals with avoidant attachment styles cannot receive emotional support or engage in looking outward through interactions with Facebook ties. Thus, they avoid these interactions.7,9

Regarding anxious–ambivalent attachment, study 1 showed that it has a positive association with online bonding capital. Additionally, mediation analyses showed that anxious–ambivalent attachment has an indirect effect on both online and offline social capital through Facebook use. These findings support the poor-get-richer hypothesis,36,37 in which those who have disadvantages in social relationships gain compensated support through Facebook. As attachment theory illustrates, individuals with an anxious orientation are eager to be close to others but hold anxious–ambivalent attitudes toward other individuals.21 The current findings show that Facebook could be a potentially beneficial tool to reduce the effect of this negative attitude toward social interactions on social capital. Although their innate internal working model prohibits individuals with anxious–ambivalent attachment from comfortably enjoying and perceiving social capital in the same way as those with secure attachment, Facebook use may provide a venue for anxious–ambivalent individuals to adjust their social interactions in this setting and lead to greater levels of perceived online and offline social capital.

In addition to attachment style and Facebook time, the role of interaction with types of friends on Facebook was explored in this study. Types of friends can be categorized as a continuum between strong and weak ties, which are highly relevant to bonding and bridging capital. The research showed that interacting with good friends on Facebook had a positive association with online and offline capital, and interaction frequency with average friends was related to online bridging capital. These nuanced findings suggest that types of connections and attachment style influence social capital. Future research should continue to explore how attachment style influences the interaction with different ties to form social capital.

This study contributes to the existing literature by providing support for attachment style as a significant antecedent of social relationships on Facebook after controlling for extraversion.20 Additionally, this study extends the attachment style results from university students to a national sample, providing greater generalizability to attachment theory. Two studies each demonstrated the consistent effect of attachment style on different dimensions of social capital and illustrated the potential effect on offline social capital. Samples from Taiwan, which is classified as a collectivist culture,38,39 show that attachment style has no cultural differences compared with U.S.,20 British,21 Israeli,6 and Korean22 samples. Moreover, types of Facebook interactions and ties and offline social capital were examined in this study to provide more nuance to current applications of attachment theory.

The main limitation of this study is the restriction of the questionnaire items that were included in the survey. This study chose to employ a validated simple measurement15 rather than the complicated four-category dimension.16 However, the results are still robust with the theory and with previous research.22 The current results can be generalized to only users in natural Facebook interactions because this study did not consider “purposive networking,” such as hosting Facebook fan pages for popularity. Readers should take caution when interpreting the results in study 2 because of the low explained variance. Nevertheless, both studies showed that attachment style matters, even when controlling for extraversion. Additionally, attachment style is a distinct construct from extraversion. Future studies should further explore the association between personality traits and attachment styles on social capital.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology under grant #100-2420-H-004-049-SS3 and #101-2410-H-009-001-SS2, and also received support by the Aiming for the Top University Plan of National Cheng Chi University.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends”: social capital and college students' use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2007; 12:1143–1168 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin JH, Peng W, Kim MJ, et al. Social networking and adjustments among international students. New Media & Society 2012; 14:421–440 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gil de Zúñiga H, Jung N, Valenzuela S. Social media use for news and individuals' social capital, civic engagement and political participation. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication 2012; 17:319–336 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granovetter MS. The strength of weak ties. The American Journal of Sociology 1973; 78:1360–1380 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 1988; 94:S95–S120 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaakobi E, Goldenberg J. Social relationships and information dissemination in virtual social network systems: an attachment theory perspective. Computers in Human Behavior 2014; 38:127–135 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowlby J. (1969) Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sroufe LA, Waters W. Attachment as an organizational construct. Child Development 1977; 48:1184–1199 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowlby J. (1988) A secure base: parent–child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowlby J. (2005) A secure base: clinical applications of attachment theory. Vol. 393 New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowlby J. (2008) A secure base: parent–child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartholomew K. Avoidance of intimacy: an attachment perspective. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships 1990; 7:147–178 [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Ruiter C, Van Ijzendoorn MH. Agoraphobia and anxious–ambivalent attachment: an integrative review. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 1992; 6:365–381 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, et al. (1978) Patterns of attachment: a psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 1987; 52:511–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 1991; 61:226–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Adult romantic attachment: theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology 2000; 4:132–154 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenny ME, Rice KG. Attachment to parents and adjustment in late adolescent college students current status, applications, and future considerations. The Counseling Psychologist 1995; 23:433–456 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buote VM, Wood E, Pratt M. Exploring similarities and differences between online and offline friendships: the role of attachment style. Computers in Human Behavior 2009; 25:560–567 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, Wright SL, Hudiburgh LM. The relationships among attachment style, personality traits, interpersonal competency, and Facebook use. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 2012; 33:294–301 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oldmeadow JA, Quinn S, Kowert R. Attachment style, social skills, and Facebook use amongst adults. Computers in Human Behavior 2013; 29:1142–1149 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee DY. The role of attachment style in building social capital from a social networking site: the interplay of anxiety and avoidance. Computers in Human Behavior 2013; 29:1499–1509 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin N. Building a network theory of social capital. Connections 1999; 22:28–51 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granovetter MS. The strength of weak ties: a network theory revisited. Sociological Theory 1983; 1:201–233 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subrahmanyam K, Reich SM, Waechter N, et al. Online and offline social networks: use of social networking sites by emerging adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 2008; 29:420–433 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. Connection strategies: social capital implications of Facebook-enabled communication practices. New Media & Society 2011; 13:873–892 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinfield C, Ellison NB, Lampe C. Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 2008; 29:434–445 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reis HT, Sheldon KM, Gable SL, et al. Daily well-being: the role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 2000; 26:419–435 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams D. On and off the “net”: scales for social capital in an online era. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2006; 11:593–628 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hair J, Black W, Babin B, et al. (2010) Multivariate data analysis. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manago AM, Taylor T, Greenfield PM. Me and my 400 friends: the anatomy of college students' Facebook networks, their communication patterns, and well-being. Developmental Psychology 2012; 48:369–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bessière K, Kiesler S, Kraut R, et al. Effects of Internet use and social resources on changes in depression. Information Communication & Society 2008; 11:47–70 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs 2009; 76:408–420 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayes AF. (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taiwan Communication Survey. Taiwan Communication Survey 2013 Annual Survey. 2013. www.crctaiwan.nctu.edu.tw/AnnualSurvey_e.asp (accessed June22, 2014)

- 36.Kraut R, Patterson M, Lundmark V, et al. Internet paradox: a social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist 1998; 53:1017–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraut R, Kiesler S, Boneva B, et al. Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues 2002; 58:49–74 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hofstede G. (1984) Culture's consequences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandez DR, Carison DS, Stepina LP, et al. Hofstede's country classification 25 years later. Journal of Social Psychology 1997; 137:43–54 [Google Scholar]