Abstract

Context

During the past 2 decades, a major transition in the clinical characterization of psychotic disorders has occurred. The construct of a clinical high-risk (HR) state for psychosis has evolved to capture the prepsychotic phase, describing people presenting with potentially prodromal symptoms. The importance of this HR state has been increasingly recognized to such an extent that a new syndrome is being considered as a diagnostic category in the DSM-5.

Objective

To reframe the HR state in a comprehensive state-of-the-art review on the progress that has been made while also recognizing the challenges that remain.

Data Sources

Available HR research of the past 20 years from PubMed, books, meetings, abstracts, and international conferences.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Critical review of HR studies addressing historical development, inclusion criteria, epidemiologic research, transition criteria, outcomes, clinical and functional characteristics, neurocognition, neuroimaging, predictors of psychosis development, treatment trials, socioeconomic aspects, nosography, and future challenges in the field.

Data Synthesis

Relevant articles retrieved in the literature search were discussed by a large group of leading worldwide experts in the field. The core results are presented after consensus and are summarized in illustrative tables and figures.

Conclusions

The relatively new field of HR research in psychosis is exciting. It has the potential to shed light on the development of major psychotic disorders and to alter their course. It also provides a rationale for service provision to those in need of help who could not previously access it and the possibility of changing trajectories for those with vulnerability to psychotic illnesses.

In our opinion, prevention of psychosis in the pre-psychotic precursor stages is possible.

Gerd Huber, 19871

During the past 2 decades, a transition in the clinical characterization of psychotic disorders has occurred. The construct of a clinical high-risk state for psychosis (hereinafter: HR) (also known as the “at-risk mental state” [ARMS],2 “prodromal,” and “ultra-high-risk” [UHR] state) has evolved to capture the prepsychotic phase, describing people presenting with potentially prodromal symptoms.3 The importance of this HR stage of psychosis has been increasingly recognized to such an extent that an attenuated psychosis syndrome is being considered as a new diagnostic category in the DSM-5.4 This category was introduced with the goal of developing treatments for prevention of psychotic disorders.5-9 However, its role as a diagnosis is being debated.10-15 This new conceptualization of the HR state would see indicated prevention16 of psychotic disorder as just one of many treatment outcomes. Prodromal symptoms and signs of psychosis are, thus, considered pleiotropic and are related to several potential outcomes, including the development of nonpsychotic disorders, rather than being unique to psychotic disorders. Thus, the proposed syndrome in the forthcoming DSM-5 can be considered analogous to chest pain (a condition requiring diagnosis and treatment and possibly indicating myocardial infarction but also a sign of possible pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, panic attack, or gastroesophageal reflux) rather than to hyperlipidemia (an asymptomatic risk factor for myocardial infarction).

Ideally, in early detection and intervention of psychosis, we would like to prevent or postpone the psychotic onset. If disease-modifying therapies or effective lifestyle preventive interventions were available, these could be started before any clinical signs appear. However, these treatments are not on the immediate horizon.17 Thus, the HR construct serves as a clinical stage in which further research is warranted. The objective of this article is to provide a comprehensive state-of-the-art review of the progress that has been made, while also recognizing the challenges that remain, based on the contributions of the leading experts in the field of prodromal psychosis.

Methods

Relevant articles from the past 20 years retrieved in the literature search (PubMed, books, meetings, abstracts, and international conferences) were critically reviewed by worldwide experts in the field. Results are presented after consensus and are summarized in illustrative tables and figures.

Results

History

Although early symptoms of psychosis have long been recognized,18 the term prodromal was first introduced by Mayer-Gross in 1932.19 It formally appeared in PubMed literature in 1989 in a pioneering work by Huber and Gross,20 who, influenced by Mayer-Gross' observations, first described basic symptoms (BS) in the 1960s and initiated the first prospective early detection study in the 1980s. In 1989, Häfner et al,21 for the first time, examined the prodrome on a representative population of 232 first-admitted psychosis patients of a large catchment area in and around Mannheim, Germany, in the ABC (Age, Begin, and Course of Schizophrenia) study.22-25 It was shown that in 73% of all the patients, the disorder began with a prodromal phase, which lasted, on average, 5 years.23,24

In 1991, Jackson and McGorry26 started reliability studies to assess first-episode patients via a semistructured interview to determine the presence or absence of the prodromal symptoms. On the basis of this work, Yung et al27 established the first clinical service for potentially prodromal individuals (1995) and began investigating the predictive validity of the prospectively defined ARMS criteria, developing the first UHR psychometric instrument. These and other investigations of early detection and intervention in the prodrome and first-episode psychosis were the subject of an early collection of articles on this topic.27-35

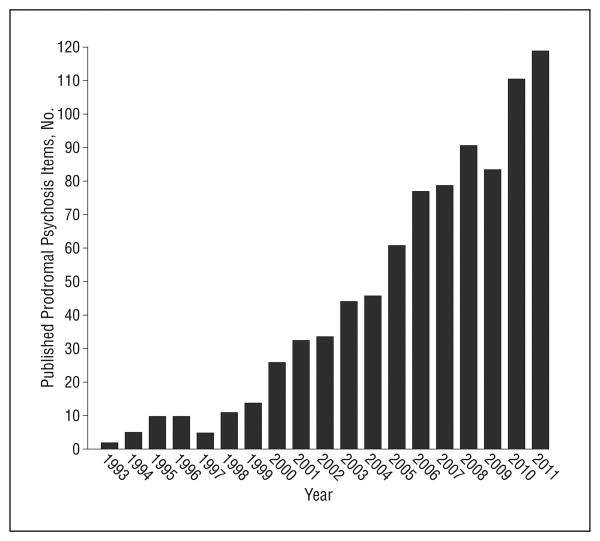

In the following years, in the United States, Miller and McGlashan36 developed a similar psychometric instrument for quantitatively rating symptom severity for patients at UHR for psychosis.37 In Europe, the further development of the BS approach for identifying individuals at HR was grounded in the diagnostic validation of a scale for the assessment of BS (1996),38 as implemented by the investigations of the group led by Klosterkötter et al.39 All the previously mentioned preliminary investigations have put forth operationalized HR diagnostic criteria, as outlined in Table 1 and described in the following subsection. These criteria have been the subject of a great deal of study and validation, as well as criticism. The explosion of interest in the literature has been remarkable, as characterized in Figure 1.

Table 1. Clinical High-Risk (HR) Criteria for Psychosisa.

| Instrument | Basic Symptomsb | Genetic Risk and Deterioration Syndrome | Brief Limited Intermittent Psychotic Episode | Attenuated Psychotic Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAARMS | NA | Family history of psychosis OR an individual with schizotypal personality disorder AND a decline in functioning OR sustained low functioningc | Transient psychotic symptoms: symptoms in the subscales of unusual thought content, nonbizarre ideas, perceptual abnormalities, disorganized speech; duration of the episode <1 wk; spontaneous remission; symptoms occurred within the past 12 mo; AND decline in functioning OR sustained low functioningc,d | Subthreshold attenuated positive symptoms: eg, ideas of reference, “magical” thinking, perceptual disturbance, paranoid ideation, odd thinking and speech; held with either subthreshold frequency or subthreshold intensity; present for>1 wk in the past 12 mo AND decline in functioning OR sustained low functioningc |

| SIPS/SOPS | NA | First-degree relative with a psychotic disorder OR an individual with schizotypal personality disorder AND a significant decrease in functioning in the past month compared with 1 year agoe | Transient psychotic symptoms in the realm of delusions, hallucinations, disorganization; intermittently for at least several minutes per day at least once per month, but <1 h/d, <4 d/wk over 1 mo. Onset in past 3 mo. Symptoms are not seriously disorganizing or dangerousf | Subthreshold attenuated positive symptoms: eg, unusual ideas, paranoia/suspiciousness, grandiosity, perceptual disturbance, conceptual disorganization; without psychotic-level conviction; onset or worsening in the past year; frequency: ≥1/wk in the past month |

| SPI-A / SPI-CY | Cognitive-perceptive basic symptoms (COPER): ≥1 of 10 basic symptoms with a score of ≥3 in the past 3 mo and first occurrence ≥1 y ago irrespective of earlier frequency or persistence AND/OR cognitive disturbances (COGDIS): ≥2 of 9 basic symptoms with a score of ≥3 in the past 3 mo | NA | NA | NA |

| BSIP | NA | Genetic risk AND further risk factors according to screening instrument (eg, social decline, unspecific prodromes) OR unspecified category: combination and minimal amount of certain unspecific risk factors/prodromes | Transient psychotic symptoms above transition cutoff each time <1 wk with spontaneous remissiong | Subthresholded attenuated positive symptoms at least several times per week, in total persisting for>1 wk |

Abbreviations: BS, basic symptom; BSIP, Basel Screening Instrument for Psychosis; CAARMS, Comprehensive Assessment of the At-Risk Mental State; NA, not assessed; SIPS, Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes; SOPS, Scale of Prodromal Symptoms; SPI-A, Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, adult version SPI-CY, Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, child and youth version.

Adapted from Cannon et al.40 Early Recognition Inventory for the Retrospective Assessment of the Onset of Schizophrenia inclusion criteria are not shown.

Basic symptoms include COPER (cognitive-perceptive symptoms) and COGDIS (cognitive disturbances).

A significant decline in functioning is defined as a Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) score at least 30% below the previous level of functioning, occurring within the last year and sustained for at least 1 month; a sustained low functioning is defined as a SOFAS score of 50 or less for the past 12 months or longer.

CAARMS: a first-episode psychosis is diagnosed when psychotic symptoms extend for more than 1 week.

A significant decrease is defined as a 30% decrease in Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score from premorbid baseline.

SIPS: a first-episode psychosis is diagnosed when psychotic symptoms extend more than 1 h/d for more than 4 d/wk during 1 month OR when they are seriously disorganizing and dangerous.

BSIP: a first-episode psychosis is diagnosed above the transition cutoff (Brief Psychiatric Rating Scales scores of hallucination ≥4, delusions ≥5, unusual thought content ≥5, and suspiciousness ≥5 and symptoms persist for >1 week).

Figure 1.

Prodromal psychosis items published in each year across the electronic databases. The literature search is updated to December 2011.

Hr Criteria

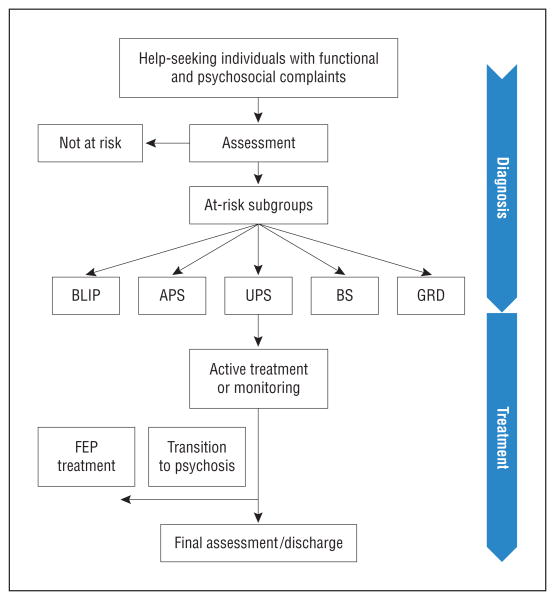

The diagnostic flowchart of HR individuals is depicted in Figure 2. Two broad sets of criteria have been used to diagnose the HR state: UHR and BS criteria41 (Table 1). These criteria are used in help-seeking individuals aged 8 to 40 years.

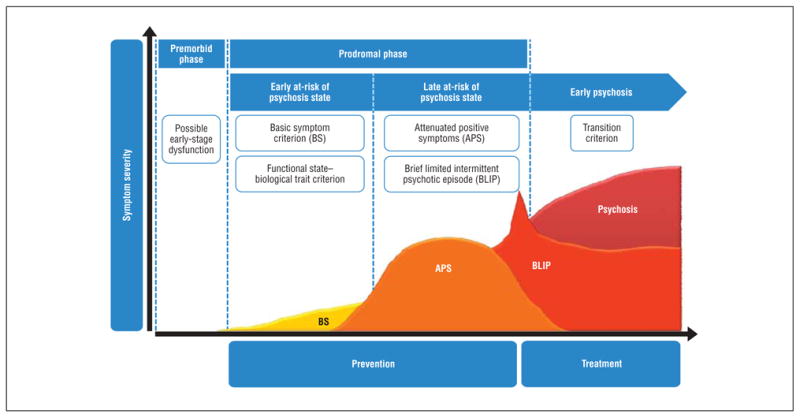

Figure 2.

Clinical management (diagnosis and treatment) flowchart of the clinical high-risk state (HR) for psychosis. APS indicates attenuated psychotic symptoms subgroup; BLIP, brief limited intermittent psychotic episode subgroup; BS, basic symptoms subgroup; FEP, first-episode psychosis; GRD, genetic risk and deterioration syndrome subgroup; and UPS, unspecified prodromal symptoms subgroup.

The UHR criteria have been the most widely applied in the literature to date.6,42-48 Inclusion requires the presence of 1 or more of the following: attenuated psychotic symptoms (APS), brief limited intermittent psychotic episode (BLIP), and trait vulnerability plus a marked decline in psychosocial functioning (genetic risk and deterioration syndrome [GRD]) and unspecified prodromal symptoms (UPS). Different interview measures have been developed to assess UHR features and to determine whether individuals meet the previously mentioned criteria: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental State (CAARMS), the Structured Interview for Prodromal Symptoms (SIPS) (including the companion Scale of Prodromal Symptoms [SOPS]), the Early Recognition Inventory for the Retrospective Assessment of the Onset of Schizophrenia (ERIraos), and the Basel Screening Instrument for Psychosis (BSIP). The CAARMS was developed by Yung et al49 at the Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation clinic in Melbourne and has been widely used in Australia, Asia, and Europe. The ERIraos was developed by Häfner et al22 to assess schizophrenia onset, and it is used in some German and Italian studies. The BSIP was developed in the Early Detection of Psychosis Clinic in Basel by Riecher-Rössler et al.50 It differs slightly from the other 2 instruments by also including a fourth at-risk category of individuals with certain combinations of risk factors and UPS.51 Miller et al52 developed the SIPS/SOPS, which have become the instruments most used in North America and Europe. A self-rating prodromal screening questionnaire has also been developed and validated.53

Basic symptoms (BS) are subjectively experienced disturbances of different domains, including perception, thought processing, language, and attention, that are distinct from classic psychotic symptoms in that they are independent of abnormal thought content and reality testing and insight into the symptoms' psychopathologic nature is intact.54 Studied prospectively in several studies,45,55-58 BS were originally assessed using the Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms (BSABS)58,59 and, more recently, the Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, adult version (SPI-A)59 and child and youth version (SPI-CY).60 A special version for children and adolescents seemed necessary to allow for developmental issues and a distinct clustering of symptoms in this age group.39 Besides a variety of subjective disturbances in affect, drive, stress tolerance, and body perception, these instruments focus on self-perceived cognitive and perceptual changes, ultimately clustered in 2 partially overlapping subsets relating to the COPER criteria (10 cognitive-perceptive BS) and the COGDIS criteria (the 9 cognitive BS that are the most predictive of later psychosis).56 Because the UHR and BS criteria relate to complementary sets of clinical features, with the BS criteria perhaps identifying an earlier prodromal state and the UHR criteria reflecting a somewhat later phase,61,62 there is an increasing tendency for centers to use both when assessing HR individuals.63 Furthermore, the simultaneous presence of UHR and COGDIS seems to be associated with higher transition risks.45 In the German Research Network on Schizophrenia,47 which introduced the BS/UHR-based 2-stage model of early and late risk,61 the ERIraos has been used to assess UHR and BS criteria.25 The assumed natural history of the HR state and the model of psychosis onset developed according to the previously mentioned criteria are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Model of psychosis onset from the clinical high-risk state. The higher the line on the y-axis, the higher the symptom severity.

Epidemiologic Research

As all HR criteria rely on help-seeking individuals, the prevalence of the HR state in the general population is unknown.64 The available epidemiologic research, based on fully structured lay person interviews and questionnaires for the assessment of psychotic symptoms, which have been shown to generate results different from those of clinical interviews,65,66 estimates a prevalence of approximately 4% to 8% for psychotic symptoms or psychotic-like experiences: such symptoms may be associated with a degree of distress and help-seeking behavior but do not necessarily amount to clinical psychotic disorder.67 However, studies in children have indicated that even frank psychotic symptoms occur in nearly every 10th child but frequently possess little clinical relevance and remit without intervention. Research is needed to examine whether current at-risk criteria must be tailored to the special needs of children.68 A pilot69 to a currently conducted study assessing HR criteria according to the SIPS and BS criteria on the telephone by trained clinicians found much lower prevalence risks of 2% in 16- to 40-year-olds. Another recent study70 in a general population sample of 212 adolescents who attend school (aged 11-13 years) estimated that up to 8% met the APS criteria for a risk syndrome according to the SIPS criteria, whereas only 1% did so when also considering the CAARMS disability criterion. Notably, 89% of adolescents with any APS reported distress caused by them. Thus, approximately 6.9% in this adolescent population fulfilled the APS and the distress criterion necessary to diagnose the proposed DSM-5 syndrome (see later herein).

Transition Criteria

In the HR literature, a variety of criteria have been used to define the transition to psychosis.71 Typically, these criteria are based on the definition given by Yung et al.72 They require the occurrence of at least 1 fully positive psychotic symptom several times a week for more than 1 week.5 Similarly, the SIPS criteria require the presence of at least 1 fully positive psychotic symptom several times per week for at least 1 month or at least 1 fully psychotic symptom for at least 1 day if this symptom is seriously disorganizing or dangerous52 (Table 1).

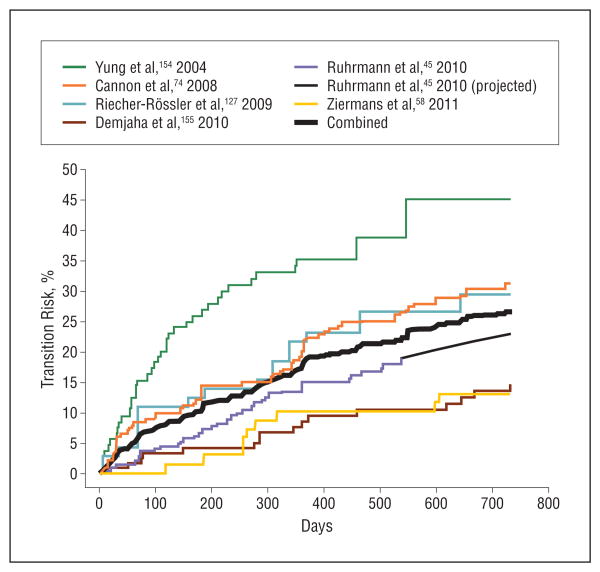

Outcomes

A key concept to emerge from work in this area is that although people with potentially prodromal features are at greatly increased risk for a psychotic disorder, mostly in a relatively short period,73 less than 40% will actually develop one. The risk of transition to psychosis in samples of HR individuals has varied between studies, with declining risks in recent years.42 In a recent meta-analysis74 of approximately 2500 HR individuals, it was shown that there was a mean (95% CI) transition risk, independent of the psychometric instruments used, of 18% (12%-25%) at 6 months of follow-up, 22% (17%-28%) at 1 year, 29% (23%-36%) at 2 years, 32% (24%-35%) at 3 years, and 36% (30%-43%) after 3 years74 (Figure 4). In individuals who will later transition to psychosis, most will develop a DSM/ICD schizophrenia spectrum disorder.75 Possible causes of the apparent decline in transition risks include (1) treatment of HR patients preventing or delaying psychosis onset; (2) a lead-time bias, that is, earlier detection resulting in transitions seemingly occurring later; and (3) a dilution effect, that is, more “false-positives” who are not really at risk being referred to HR services, possibly as a result of these services and their intake criteria becoming more well-known.42

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of transition risks in studies reporting Kaplan-Meier estimates of psychosis transition over time in the high-risk state (n = 984 individuals) (for details of the study, see Fusar-Poli et al75). These risks are based on treated cohorts with no standardized treatment, so transition risk estimates are not for natural course or untreated cases.

To date, transition estimates in the HR state have been made in samples of help-seeking individuals who were referred because they were distressed and impaired and, thus, have a higher risk of psychosis with the need for care than do those in the general population. The number of individuals in the community who meet HR criteria remains unknown (as noted previously herein),69 and the available instruments are not indicated for screening in the general population.76 In addition, little is known about the outcome in the group of HR individuals who do not convert to psychosis, as few studies provide the characteristics of these individuals.77 In the largest study78 published to date, to our knowledge, the nonconverting group demonstrated significant improvement in attenuated positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and social and role functioning. However, this group remained, on average, at a lower level of functioning than did nonpsychiatric comparison subjects, suggesting that initial prodromal categorization is associated with persistent disability for a significant proportion.78 Furthermore, retrospective studies23,79 of patients with schizophrenia have found that some individuals develop a prodrome-like syndrome that resolves (an “outpost” syndrome) only to develop full-blown schizophrenia some time later. In the absence of long-term follow-up data in the HR literature, it remains unclear in what proportion of these nonconverters the improvement will be permanent or only temporary.54 A recently completed 15-year follow-up study80 found that HR individuals continued to develop psychotic disorder up to 10 years after initial presentation, which suggests that outpost syndromes may be a possibility in a subset of individuals. This long-term perspective may, therefore, be in line with the 9.6-year 65% (COPER) to 79% (COGDIS) transition risk in BS studies.55

Clinical and Functional Characteristics

In addition to HR symptoms, people who meet the criteria for HR in help-seeking populations usually present with other clinical concerns. Many have comorbid diagnoses, in particular anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders, that are clinically debilitating.81,82 High levels of negative symptoms, significant impairments in academic performance and occupational functioning, and difficulties with interpersonal relationships and substantially compromised subjective quality of life83 are often observed.81,84-86 The experience of HR symptoms per se is also associated with a marked impairment in psychosocial functioning86 which appears as a core feature of the HR state.87 Social impairment is a predictor of longitudinal outcome86,88 and tends to be resistant to treatment (pharmacological and psychosocial).89 It is also reflected by a considerably decreased subjective quality of life.83,90

The HR state might also be associated with increased suicidality. In a small pilot sample, 59% of HR patients who accepted treatment presented with at least mild suicidal ideation, and 47% reported at least 1 suicide attempt before being accepted in an early intervention service.91

Neurocognition

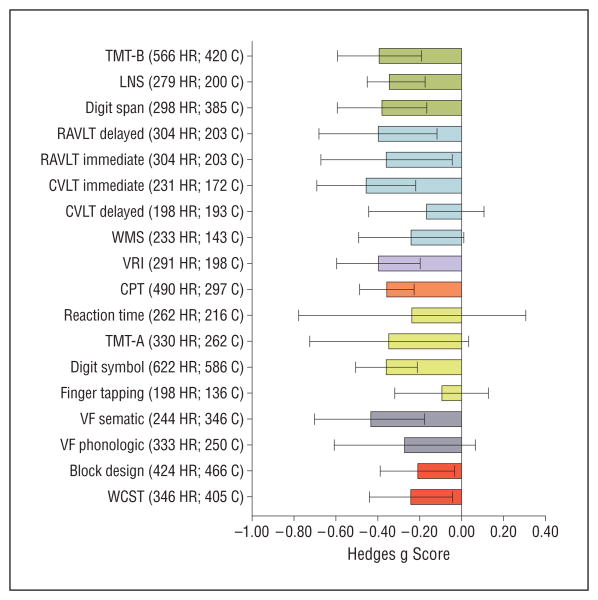

Neurocognitive studies in the HR population have attempted to establish whether the deficits observed during a first episode of psychosis were already evident during the prepsychotic phases. Two recent meta-analyses of more than 1000 HR individuals matched with control subjects yielded small-to-medium impairments across most neurocognitive domains (Figure 5).93,94 Widespread mild cognitive deficits are present in HR individuals, falling at a level that is intermediate between that of healthy individuals and those diagnosed as having schizophrenia87 and comparable with those at familial (“genetic”) risk and with follow-back premorbid data.92 These deficits have been found to be predictive of functioning in the HR group.95 Further deficits have been observed in the social cognition domain,94 which is considered a good predictor of functional and psychosocial outcomes.96 Moreover, HR individuals who convert to psychosis show more severe neurocognitive deficits at baseline than do nonconverters in nearly all domains (eFigure; http://www.archgenpsychiatry.com),93 in particular in the verbal fluency and memory domains.94 However, there is considerable heterogeneity across studies, which underscores the variability in phenotypic expression or measurement sensitivity, and a critical need for future prospective longitudinal studies designed to assess the different trajectories of HR cognitive changes. The mild cognitive deficits of most HR individuals may account for the presenting symptoms and problems. These deficits are often more of a concern to the individual than is their long-term risk of transition,88 and may predict poor psychosocial functioning.97,98

Figure 5.

Neurocognitive profiles of individual tasks in high-risk individuals (n = 1188) compared with controls (n = 1029).92 Mean Hedges g scores are shown across cognitive tasks (negative values indicate worse performance in high-risk individuals compared with the control group). Error bars represent 95% CI. C indicates number of controls; CPT, Continuous Performance Test (d prime); CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; HR, number of high-risk individuals; LNS, Letter Number Sequencing; RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; TMT-A, Trail Making Test Part A; TMT-B, Trail Making Test Part B; VF, Verbal Fluency; VRI, Visual Reproduction Index (WMS visual reproduction and Rey complex figures); WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (perseverative errors); and WMS, Wechsler Memory Scale (verbal recall). Working memory is shown in green, verbal memory in blue, visual memory in violet, attention in orange, processing speed in yellow, verbal fluency in gray, and executive functions in red.

Structural, Functional, and Neurochemical Imaging

A major goal of studies of people at HR for psychosis has been to find neuroimaging indicators of psychosis vulnerability.99 Early studies focused on detecting specific volumetric reductions in regions known to be affected in schizophrenic psychoses, such as the hippocampus100,101 and the anterior cingulate cortex.102 Although significant differences have been seen compared with healthy samples, overall, these seem to be smaller than those evident in people with frank psychosis.103 Although replication of significant findings is a problem for the field as a whole, volumetric reductions in the temporal,104 cingulate,104 insular,105 prefrontal,105 and parahippocampal106 cortices have been associated with later development of psychosis. Furthermore, there is some evidence that structural brain imaging can be used to classify HR individuals in terms of their future clinical outcome.107 However, there is enormous variability in findings, highlighting the heterogeneity of the population and the likely lack of sensitivity for volumetric measures alone.

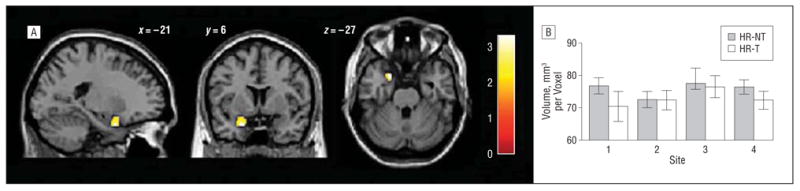

More recent studies have used alternative imaging methods to examine the extent of baseline abnormalities in HR populations. Functional magnetic resonance imaging tasks have shown changes in activation in HR samples that are intermediate between those in first-episode patients and controls,108,109 although no replication studies have been published. Results of brain spectroscopy studies have suggested some differences in metabolite concentration, but samples are small and the regions studied are highly variable.110-112 More promising are data from positron emission tomography studies, which indicate elevated striatal dopamine synthesis in HR individuals113 that is greater in those who later convert to psychosis114 and consistent with the finding of 14% elevation in established schizophrenia.115 Similarly, electrophysiologic abnormalities have been associated with the HR state.116,117 Several critical reviews and meta-analyses of structural,105,118,119 functional,120 and neurochemical115,121-123 imaging findings in the HR state124 are now available. The results of the largest multicenter structural neuroimaging study in HR individuals published to date106 are depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Structural brain alterations observed in the largest multisite neuroimaging studies of high-risk (HR) individuals (n = 182) and matched controls (n = 167).107 Baseline differences are shown between HR individuals who did (HR-T, n = 48) and did not (HR-NT, n = 134) develop psychosis during the following 2 years. The HR-T individuals had less gray matter volume than did the HR-NT individuals in the left parahippocampal gyrus, bordering the uncus. The plot shows mean gray matter volumes for the 2 HR subgroups at each site (1 indicates London, United Kingdom; 2, Basel, Switzerland; 3, Munich, Germany; and 4, Melbourne, Australia). Error bars represent SD.

Advanced multimodal imaging techniques showed that dysfunction in dopamine and glutamate systems, both widely implicated in the pathogenesis of psychosis, directly correlated with altered cortical structure110 and functioning125-127 in HR individuals. Although further longitudinal neuroimaging studies are required to confirm the previously mentioned preliminary results, these recent findings suggest that advanced neuroimaging methods may have additional predictive value for detecting individuals at particularly high risk for psychosis.

Predictors of Psychosis

Can we predict who among HR individuals will progress to full-blown psychosis? A great deal of research on this issue has been generated in the last decade, and it has been shown that prediction of actual transition in those identified with HR criteria can be further improved by a stepwise multilevel assessment.128 We focus herein on the clinical predictors of psychosis onset; available studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Clinical Predictors of Transition to Psychosis From the HR State in Studies Enrolling at Least 60 Individuals and Reporting Regression Models of Significant Clinical Predictorsa.

| Source | HR Group | HR Sample, No. | PR, % | Follow-up, y | Predictors | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| PPV | SE | SP | ||||||

| Klosterkötteretal,55 2001 | BS | 160 | 49 | 9.6 | (1-4) Thought interference, pressure, preservation, blockages, (5) disturbance of receptive language, (6) unstable ideas of references, (7) derealization, (8-9) visual/acoustic perception disturbances,(10) inability to discriminate between ideas and perception, fantasy, and true memoryb | 65 | 87 | 54 |

| Mason et al,129 2004 | UHR | 74 | 50 | 2 | (1) Odd beliefs/magical thinking, (2) marked impairment in role functioning, (3) blunted or inappropriate affect,(4) auditory hallucinations, (5) anhedonia/asocialityc | 86 | 84 | 86 |

| Yung et al,130 2004 | UHR | 104 | 39 | 2.3 | (1) Attenuated psychosis symptoms + genetic risk, (2) long duration of prodromal symptoms, (3) poor social functioning, (4) poor attentiond | 81 | 60 | 93 |

| Thompson et al,131 2011 | (1) High unusual thought content scores;(2) low functioning; (3) having genetic risk with functional declinee | 64 | 17 | 94 | ||||

| Cannon et al,73 2008 | UHR | 291 | 35 | 2.5 | (1) A genetic risk for schizophrenia with recent deterioration in functioning, (2) higher levels of unusual thought content, (3) higher levels of suspicion/paranoia, (4) greater social impairment, (5) and a history of substance abusec | 79 | 8 | 98 |

| Riecher-Rössler et al,128 2009 | UHR | 64 | 34 | 5.4 | (1) Attenuated psychotic symptoms (suspiciousness), (2) negative symptoms (anhedonia/asociality), (3) cognitive deficitsf | 81 | 83 | 79 |

| Ruhrmann et al,45 2010 | UHR + BS | 245 | 19 | 1.5 | (1) Positive symptoms, (2) bizarre thinking, (3) sleep disturbances, (4) schizotypal disorder, (5) level of functioning in the past year, (6) years of educationg | 83 | 42 | 98 |

| Demjaha et al,132 2010 | UHR | 122 | 15 | 2 | (1) Negative, (2) cognitive/disorganized CAARMS domains | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: BS, basic symptoms; CAARMS, Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental State; HR, clinical high risk for psychosis; NA, not available; PPV positive predictive value; PR, psychosis risk; SE, sensitivity; SP, specificity; UHR, ultra high risk.

Schultze-Lutter et al56 found no significant predictive power for Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale negative scores.

Model based on cognitive-perceptive symptoms.

Five-factor model.

Model requiring the presence of at least 1 of the 4 potential predictors.

Three-factor model.

Combined model.

Six-factor model (schizotypal disorder: symptom criteria >1 year); resulting in prognostic index with 4 risk classes (PR 3.5, 8.0, 18.4, 85.1).

An early study55 showed that the absence of BS in HR individuals excluded a subsequent schizophrenia with a probability of 96%. More recently, the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study87 reported 5 clinical predictive variables in their sample of HR participants: genetic risk with functional decline, high unusual thought content scores, high suspicion/paranoia scores, low social functioning, and history of substance abuse. Three of the 5 variables were replicated to be associated with transition in an independent cohort from the Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation sample: high unusual thought content scores, low functioning, and genetic risk with functional decline.131 In the European Prediction of Psychosis Study,45 a clinical prediction model including 6 variables produced favorable accuracy results. In this study, the regression equation was used to introduce a prognostic index that allows stratification of risk into 4 classes, thereby avoiding the considerable loss of sensitivity resulting from narrowing of criteria. A more individualized risk estimation or clinical staging of risk could significantly advance the development of risk-adapted inclusion criteria for randomized preventive trials.62 In the Basel Early Detection of Psychosis Clinic study, with follow-up of up to 7 years, HR individuals with high suspiciousness and high anhedonia/asociality scores had an especially high transition risk.128

Prediction of psychosis could be further improved by combining the clinical markers with a family history of psychosis, neurocognitive128,133 or electrophysiologic134 measures, by investigating environmental factors,98 by conducting multicenter studies,106 by using advanced imaging voxel-based meta-analyses,106,119 or by adopting automated analysis methods.107,135 The latter point is addressed by recent studies using multivariate neurocognitive pattern classifications to facilitate the HR diagnosis and the individualized prediction of illness transition.135 Classification accuracy was 91% for converters and 89% for nonconverters. Psychosis transition was mainly predicted by executive and verbal learning impairments.135 Similarly, multivariate neuroanatomical gray matter pattern classification was 88% for individuals with later transition and 86% for those without.107 However, a definitive conclusion concerning these predictions awaits replication in future studies.

Treatment Trials

Preventive interventions in psychosis are feasible and can be effective. Most trials indicate clinically meaningful advantages of focused treatment (psychological, psychopharmacologic, or neuroprotective interventions) compared with the respective contrast groups. A recent review136 of treatment effectiveness in the HR state concluded that receiving focused treatment from specialized services was associated with lower risk of psychosis at 12 months and at 24 to 36 months. However, no reliable recommendations can be made regarding whether psychosocial interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy; potentially neuroprotective agents, such as ω-3 fatty acids; or antipsychotic agents are more effective for the prevention of psychosis in HR. Consequently, the safest approach is recommended, that is, psychological interventions and fish oil intake rather than antipsychotic drug treatment. Several large-scale clinical trials are under way, which will substantially increase the evidence base for best clinical practice in HR.137-139 We present herein an updated meta-analysis of available randomized controlled treatment trials in the HR population, which includes transition data up to 1 year. We confirmed a significant effect of active treatments, with a risk ratio of 0.34 (from 23% to 7%, P < .001) and a number needed to treat of 6 in the focused treatments vs the contrast group at 1 year. Details of the available trials are given in Table 3.

Table 3. Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Treatment Trials in HR Individuals Including Transition Data Up to 1 Year.

| Source | HR Inclusion Criteria | Focused Treatment | Contrast Group | DI, mo | NNT at 1 y, Mean (95% CI) | Transition at 1 y (Focused vs Contrast) | Meta-analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| RR (95% CI) | P Value | |||||||

| McGorry et al,7 2002a | CAARMS | Risperidone, 1-2 mg + CBT + NBI (n=31) | NBI (n = 28) | 6 | 4 (2.1-18.3) | 19.3 vs 35.7, NS | 0.541 (0.225-1.297) | .17 |

| Morrison et al,9 2004b | CAARMS based | CT (n=37) | Monitoring (n=23) | 6 | 5 (2.3-63.8) | 5.7 vs 21.7, NS | 0.263 (0.057-1.205) | .09 |

| McGlashan et al,6 2006 | SIPS | Olanzapine, 5-15 mg (n=31) | Placebo (n=29) | 12 | 5 (2.3-inf) | 16.1 vs 37.9, NS | 0.425 (0.168-1.075) | .07 |

| Ammingeretal,8 2010 | CAARMS | ω-3 PUFA, 1.2 g (n=41) | Placebo (n=40) | 3 | 5 (2.6-13.7) | 4.8 vs 27.5, Sig | 0.175 (0.041-0.746) | .02 |

| Yung et al,140 2011 | CAARMS | Risperidone, 0.5-2 mg + CT (n=43) | CT+placebo (n=44) | 6 | NA | 4.7 vs 9.1 vs 7.1, NS c | 0.516 (0.100-2.658) | .43 |

| ST+placebo (n=28) | NS | |||||||

| Addington et al,141 2011 | SIPS | CBT (n = 27) | ST (n = 24) | 6 | 8 (3.7-inf) | 0 vs 12.5, NS | 0.128 (0.007-2.350) | .17 |

| Bechdolf et al,57 2012 | EIPS | IPI (n=63) | SC (n = 65) | 12 | 8 (4.2-27.3) | 3 vs 16.9, Sig | 0.178 (0.039-0.799) | .02 |

| Overalld | 273 | 281 | 7.3 | 5.8 | 7.6 vs 23 | 0.335 (0.219-0.575) | <.001 | |

Abbreviations: CAARMS, Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental State; CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; CT, cognitive therapy; DI, duration of intervention; EIPS, early initial prodromal state (COPER or first-degree relatives with psychosis plus functional decline); HR, clinical high risk; inf, infinite; IPI, integrated psychological intervention (CT, social skills, psychoeducation for family, and cognitive remediation); NA, not assessed; NBI, needs-based intervention; NNT, number needed to treat; NS, nonsignificant differences between focused treatment and contrast group; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; RR, risk ratio; SC, supportive counseling; Sig, significant; SIPS, Structured Interview for Prodromal Symptoms; ST, supportive therapy.

See also Phillips et al.142

See also Morrison et al.143 Additional evidence suggests that preventing the start of cannabis use or stopping already started use may diminish the risk of a psychotic disorder.144

Six-month results.

Random effects models applied, Q=3.590, P=.732, I2=0.

Socioeconomic Considerations

The preliminary cost-effectiveness literature indicated that the extra costs, compared with standard care, required in the first year of treatment are compensated for by subsequent savings associated with the prevention of transition to psychosis. These benefits are mainly related to a shortening of the duration of untreated psychosis in those who develop psychosis, resulting, for example, in less need for inpatient care and a reduction in treatment costs.145,146 Although early interventions might be associated with significant cost benefits even in the long term,147 future research is required to fully address their cost-effectiveness.148

Attenuated Psychosis Syndrome

Many of the previously noted findings have informed the ongoing debate about the inclusion of an HR syndrome in the next edition of the DSM-5.4 The current proposal is to include a category of “attenuated psychosis syndrome” in the DSM-5 that is modeled on the UHR category of APS (http://www.dsm5.org). This new category was previously called the “psychosis risk syndrome.” However, the recent name change was an attempt to highlight current symptoms as the focus for treatment rather than the risk that the symptoms might pose for future psychotic disorder.11 Furthermore, the category also requires the symptoms to be sufficiently distressing and disabling to the person or a parent or guardian to lead them to seek help (eAppendix).11

At present, there is no diagnostic category in the DSM or the ICD for the HR state, although the schizotypal disorder included in the psychosis section in the ICD-10 shares several similarities with the DSM-5 proposal.10 In conventional clinical practice, HR individuals may not receive appropriate treatment despite the fact that this group experiences symptoms88,149 that are distressing enough for them to seek help and a considerably decreased quality of life.90 Defining HR as a new diagnostic category may make clinicians more likely to identify and treat these individuals. Although available evidence suggests that most HR individuals will not develop a psychotic disorder (at least within 3 years of presentation),74 the purpose of clinical management at this stage is not solely to prevent the later onset of frank illness but also to ameliorate the presenting symptoms, problems, and functional deficits. These are often more of a concern to the individual than is their long-term risk of transition.47 This finding is consistent with the newly proposed diagnostic label of attenuated psychosis syndrome rather than risk syndrome. Moreover, when HR individuals are engaged at this stage and then later develop psychosis, the delay before the latter is treated can be markedly reduced, and the first episode may be less traumatic. For clinical practice, a formal diagnosis will allow the development of treatment, not only preventionrelated approved interventions; will grant access to the health care system; and will allow the establishment of rules to guide treatment, thus avoiding undertreatment and overtreatment.10

On the other hand, there are also counter-arguments against the inclusion of the HR state in the DSM-5. Regarding the implied risk of a full-blown disorder, concerns about the substantial number of false-positive patients who are not actually at risk for psychotic disorder and the declining transition risk over the recent years remain.12 An additional concern is that there is still the danger that people meeting the criteria will be incorrectly conceptualized as being on the psychosis spectrum and that an irreversible lifelong underlying “process” has started.12,150 Unintended consequences might then ensue, including stigma across different settings and cultures of care, discrimination, and unnecessary treatment.12,15 In particular, antipsychotic drugs (which may have significant effects on the brain151) may be used, despite these medications not being recommended in any clinical guidelines for the treatment of HR individuals (see Table 4).152 Diagnostic creep may occur, resulting in lowering of the HR threshold and a subsequent reduction in transition risk.12 Finally, we may not yet know enough about factors in addition to the HR criteria that potentially increase the risk of transition. Ironically, codification of the HR state may actually reduce this necessary research in the area.15 The alternative option would be to rely on cross-diagnostic staging or a risk stratification approach, which considers the varying severity of the psychosis risk states and has the connotation that each stage may remit and not progress with optimum and timely intervention.153 This approach is likely to be less stigmatizing but requires more research to better define the stages.153

Table 4. Treatment Guidelines for the Psychosis High-Risk State Proposed by Different International Organizations.

| Organization | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| American Psychiatric Association | “Careful assessment and frequent monitoring” |

| Canadian Psychiatric Association | “Should be offered monitoring” |

| Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists | “Antipsychotic medication not normally prescribed unless symptoms are directly associated with risk of self-harm or aggression” |

| Italian Institute of Health | “Use of antipsychotic medication is doubtful, behavioral cognitive treatment is recommended” |

| German Association for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Neurology | “Continuous care and follow-up; if relevant symptoms reaching the level of a disorder occur, CBT and sociotherapy should be offered; if psychotic symptoms emerge antipsychotics should be offered” |

Abbreviation: CBT indicates cognitive behavior therapy.

Comment

Two decades of research into the prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis has brought important new knowledge. Nevertheless, many questions remain unanswered, and important challenges are still ahead. First, although there are indications that HR individuals show psychopathologic, functional, neurocognitive, and structural brain abnormalities, it is unclear to what extent these findings reflect psychiatric distress in general or are unique features associated with being on the path to a fullblown psychotic disorder. Thus, more longitudinal research comparing individuals who develop psychotic disorder with those who do not is still needed. In addition, the inclusion of other psychiatric groups as controls would help distinguish between general psychiatric symptoms and those specific to the HR state. Second, there is a need to recognize the importance of and to investigate outcomes other than schizophreniform psychosis. The focus to date has been on positive symptoms, both in terms of the inclusion criteria for the HR state and the definition of transition to psychoses. However, there is increasing evidence that negative symptoms154 and the level of cognitive and social functioning may also be meaningful measures of clinical outcomes. At present, HR individuals with poor social and role function, neurocognitive impairments, and high levels of negative symptoms may still be classified as “nontransitions” because their positive symptoms have not reached the conventional threshold for frank psychosis. Thus, these outcomes may be more relevant to an underlying schizophrenia construct than to positive symptoms alone.71,154 It is also important to ascertain whether the HR criteria detect people at risk for other nonpsychotic disorders. Third, children, adolescents, and adults may need to be considered separately in terms of presenting features, predictors, and treatment needs given their different developmental stages. Fourth, we may need to refine our thinking around trait and state risk factors for the disorder. For example, do certain neurocognitive abnormalities that are milder in HR individuals than in psychotic individuals represent state risk factors that will deteriorate further with progression of illness? Or is their intermediate nature due to the HR sample consisting of some people at risk and some not at risk? It is also important to characterize the heterogeneity of the HR subgroups as we do not know whether patients with GRD, BLIP, APS, or BS criteria have differences in neurobiological features and outcome. The fifth challenge is to test what we have learned so far in order to develop and evaluate interventions that can delay, ameliorate, or even prevent psychosis onset and illness progression or that can prevent comorbidity of other psychiatric disorders.155 For example, given evidence of social cognitive deficits in HR patients,156 could therapies addressing emotion recognition be effective? Replication of the finding that fish oil may prevent psychosis8 is needed; antidepressants,157 mood stabilizers,158 and neuroprotective factors,44 such as N-acetyl cysteine,159 may also have potential benefits. Future research could also identify potential critical intervention points where success may alter the life course of illness. Sixth, provision of services to HR individuals across different cultures and mental health structures needs consideration. Different models of service will result in different populations seeking help. An HR service that is co-located with a psychosis service may be expected to receive referrals that have a different transition risk than one located more in the community or developed as part of a general youth service, although the latter would reduce stigma more effectively. Thus, treatment models must be tailored toward the presenting problems and the expected transition risk. Initial treatment guidelines proposed by various international organizations are summarized in Table 4.

In summary, the relatively new field of HR research in psychosis is exciting. It has the potential to shed light on the development of major psychotic disorders and to alter their course. It also provides a rationale for service provision to those in need of help who could not previously access it and the possibility of changing trajectories for those with vulnerability to psychotic illness. Challenges remain and we must be mindful of premature intellectual closure in the area. There is still much work to be done.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Online-Only Material: The eAppendix and eFigure are available at http://www.archgenpsychiatry.com.

Additional Information: We dedicate the present work to professor Gerd Huber, pioneer researcher in the HR state for psychosis. At the time this article was released, a final decision was reached regarding the inclusion of APS as a new DSM-5 category, with a recommendation for APS to be in Section 3 for research and further study rather than in the main text.160

Contributor Information

Dr Paolo Fusar-Poli, Department of Psychosis Studies, King's College London, London, United Kingdom; OASIS team for prodromal psychosis, NHSSLAM Foundation Trust, London.

Dr Stefan Borgwardt, Department of Psychiatry, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

Dr Andreas Bechdolf, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany.

Dr Jean Addington, Department of Psychiatry, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Dr Anita Riecher-Rössler, Department of Psychiatry, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

Dr Frauke Schultze-Lutter, University Hospital of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

Dr Matcheri Keshavan, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Dr Stephen Wood, Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Melbourne and Melbourne Health, Melbourne, Australia; School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Dr Stephan Ruhrmann, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany.

Dr Larry J. Seidman, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Dr Lucia Valmaggia, Departments of Psychosis Studies and Psychology, King's College London, London, United Kingdom; OASIS team for prodromal psychosis, NHSSLAM Foundation Trust, London.

Dr Tyrone Cannon, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California, Los Angeles.

Dr Eva Velthorst, Department of Early Psychosis, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Dr Lieuwe De Haan, Department of Early Psychosis, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Dr Barbara Cornblatt, Department of Psychiatry Research, The Zucker Hillside Hospital, New York, New York.

Dr Ilaria Bonoldi, OASIS team for prodromal psychosis, NHSSLAM Foundation Trust, London; Department of Psychosis Studies King's College London, London, United Kingdom.

Dr Max Birchwood, School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Dr Thomas McGlashan, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

Dr William Carpenter, Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore.

Dr Patrick McGorry, Orygen Youth Health Research Centre, University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

Dr Joachim Klosterkötter, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany.

Dr Philip McGuire, Department of Psychosis Studies King's College London, London, United Kingdom; OASIS team for prodromal psychosis, NHSSLAM Foundation Trust, London.

Dr Alison Yung, Orygen Youth Health Research Centre, University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

References

- 1.Klosterkötter JGG, Huber G, Wieneke A, Steinmeyer EM, Schultze-Lutter F. Evaluation of the Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms: BSABS as an instrument for the assessment of schizophrenia proneness: a review of recent findings. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. 1997;5:137–150. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schultze-Lutter F, Schimmelmann BG, Ruhrmann S. The near Babylonian speech confusion in early detection of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(4):653–655. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, McGuire P. Vulnerability to Psychosis: From Neurosciences to Psychopathology. London, United Kingdom: Psychology Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fusar-Poli P, Yung AR. Should attenuated psychosis syndrome be included in DSM5? Lancet. 2012;379(9816):591–592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey SM, McFarlane CA, Hallgren M, McGorry PD. Psychosis prediction: 12-month follow up of a high-risk (“prodromal”) group. Schizophr Res. 2003;60(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, Addington J, Miller T, Woods SW, Hawkins KA, Hoffman RE, Preda A, Epstein I, Addington D, Lindborg S, Trzaskoma Q, To-hen M, Breier A. Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):790–799. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey S, Cosgrave EM, Germano D, Bravin J, McDonald T, Blair A, Adlard S, Jackson H. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):921–928. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amminger GP, Schafer MR, Papageorgiou K, Klier CM, Cotton SM, Harrigan SM, Mackinnon A, McGorry PD, Berger GE. Long-chain ω-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):146–154. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison AP, French P, Walford L, Lewis SW, Kilcommons A, Green J, Parker S, Bentall RP. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;(185):291–297. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J. Probably at-risk, but certainly ll: advocating the introduction of a psychosis spectrum disorder in DSM-V. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter WT., Jr Criticism of the DSM-V risk syndrome: a rebuttal. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2011;16(2):101–106. doi: 10.1080/13546805.2011.554278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yung AR, Nelson B, Thompson AD, Wood SJ. Should a “Risk Syndrome for Psychosis” be included in the DSMV? Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corcoran CM, First MB, Cornblatt B. The psychosis risk syndrome and its proposed inclusion in the DSM-V: a risk-benefit analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arango C. Attenuated psychotic symptoms syndrome: how it may affect child and adolescent psychiatry. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(2):67–70. doi: 10.1007/s00787-010-0144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drake RJ, Lewis SW. Valuing prodromal psychosis: what do we get and what is the price? Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mrazek P, Haggerty H. Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Research. Washington, DC: Academy Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGorry PD, Nelson B, Amminger GP, Bechdolf A, Francey SM, Berger G, Riecher-Rössler A, Klosterkötter J, Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Nordentoft M, Hickie I, McGuire P, Berk M, Chen EY, Keshavan MS, Yung AR. Intervention in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a review and future directions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(9):1206–1212. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08r04472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan HS. The onset of schizophrenia: 1927. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(6) suppl:134–139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.6.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer-Gross W. Die Klinik der Schizophrenie. In: Bunke O, editor. Handbuch der Geisteskrankheiten. IX. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huber G, Gross G. The concept of basic symptoms in schizophrenic and schizoaffective psychoses. Recenti Prog Med. 1989;80(12):646–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riecher A, Maurer K, Löffler W, Fätkenheuer B, an der Heiden W, Häfner H. Schizophrenia: a disease of young single males? preliminary results from an investigation on a representative cohort admitted to hospital for the first time. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1989;239(3):210–212. doi: 10.1007/BF01739655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Häfner H, Riecher-Rössler A, Hambrecht M, Maurer K, Meissner S, Schmidtke A, Fätkenheuer B, Löffler W, van der Heiden W. IRAOS: an instrument for the assessment of onset and early course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1992;6(3):209–223. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90004-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Häfner H, Maurer K, Löffler W, an der Heiden W, Munk-Jørgensen P, Hambrecht M, Riecher-Rössler A. The ABC Schizophrenia Study: a preliminary overview of the results. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33(8):380–386. doi: 10.1007/s001270050069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Häfner H, Maurer K, Läffler W, Riecher-Rässler A. The influence of age and sex on the onset and early course of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:80–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Häfner H, Riecher-Rössler A, Maurer K, Fätkenheuer B, Löffler W. First onset and early symptomatology of schizophrenia: a chapter of epidemiological and neurobiological research into age and sex differences. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1992;242(2-3):109–118. doi: 10.1007/BF02191557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, McKenzie D. The reliability of DSM-III prodromal symptoms in first-episode psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(5):375–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yung AR, McGorry PD, McFarlane CA, Jackson HJ, Patton GC, Rakkar A. Monitoring and care of young people at incipient risk of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):283–303. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention in schizophrenia: editor's introduction. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):197–199. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):353–370. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention in schizophrenia: research. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):327–345. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGorry PD, Edwards J, Mihalopoulos C, Harrigan SM, Jackson HJ. EPPIC: an evolving system of early detection and optimal management. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):305–326. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falloon IR, Kydd RR, Coverdale JH, Laidlaw TM. Early detection and intervention for initial episodes of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):271–282. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Moe LC. First-episode schizophrenia, I: early course parameters. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):241–256. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olin SC, Mednick SA. Risk factors of psychosis: identifying vulnerable populations premorbidly. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):223–240. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO. Early detection and intervention with schizophrenia: rationale. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):201–222. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, Stein K, Driesen N, Corcoran CM, Hoffman R, Davidson L. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(4):273–287. doi: 10.1023/a:1022034115078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGlashan T, Walsh B, Woods S. The Psychosis-Risk Syndrome: Handbook for Diagnosis and Follow-Up. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klosterkötter J, Ebel H, Schultze-Lutter F, Steinmeyer EM. Diagnostic validity of basic symptoms. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;246(3):147–154. doi: 10.1007/BF02189116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Fusar-Poli P, Bechdolf A, Schimmelmann BG, Klosterkötter J. Basic symptoms and the prediction of first-episode psychosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):351–357. doi: 10.2174/138161212799316064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, McGorry P. The empirical status of the ultra high-risk (prodromal) research paradigm. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):661–664. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olsen KA, Rosenbaum B. Prospective investigations of the prodromal state of schizophrenia: assessment instruments. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(4):273–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yung AR, Stanford C, Cosgrave E, Killackey E, Phillips L, Nelson B, McGorry PD. Testing the Ultra High Risk (prodromal) criteria for the prediction of psychosis in a clinical sample of young people. Schizophr Res. 2006;84(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carr V, Halpin S, Lau N, O'Brien S, Beckmann J, Lewin T. A risk factor screening and assessment protocol for schizophrenia and related psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(suppl):S170–S180. doi: 10.1080/000486700240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW, Correll CU, Auther AM, Nakayama E. The schizophrenia prodrome revisited: a neurodevelopmental perspective. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):633–651. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK, Heinimaa M, Linszen D, Dingemans P, Birchwood M, Patterson P, Juckel G, Heinz A, Morrison A, Lewis S, von Reventlow HG, Klosterkotter J. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the prospective European Prediction of Psychosis Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):241–251. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Broome MR, Woolley JB, Johns LC, Valmaggia LR, Tabraham P, Gafoor R, Bra-mon E, McGuire PK. Outreach and support in south London (OASIS): implementation of a clinical service for prodromal psychosis and the at risk mental state. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20(5-6):372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J. Early detection and intervention in the initial prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(suppl 3):S162–S167. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simon AE, Dvorsky DN, Boesch J, Roth B, Isler E, Schueler P, Petralli C, Umbricht D. Defining subjects at risk for psychosis: a comparison of two approaches. Schizophr Res. 2006;81(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell'Olio M, Francey SM, Cosgrave EM, Killackey E, Stanford C, Godfrey K, Buckby J. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11-12):964–971. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riecher-Rössler A, Gschwandtner U, Aston J, Borgwardt S, Drewe M, Fuhr P, Pflüger M, Radü W, Schindler Ch, Stieglitz RD. The Basel early-detection-of-psychosis (FEPSY)-study: design and preliminary results. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115(2):114–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riecher-Rössler A, Aston J, Ventura J, Merlo M, Borgwardt S, Gschwandtner U, Stieglitz RD. The Basel Screening Instrument for Psychosis (BSIP): development, structure, reliability and validity [in German] Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2008;76(4):207–216. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Cannon T, Ventura J, McFarlane W, Perkins DO, Pearlson GD, Woods SW. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):703–715. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loewy RL, Bearden CE, Johnson JK, Raine A, Cannon TD. The Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ): preliminary validation of a self-report screening measure for prodromal and psychotic syndromes. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(1):117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schultze-Lutter F. Subjective symptoms of schizophrenia in research and the clinic: the basic symptom concept. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(1):5–8. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klosterkötter J, Hellmich M, Steinmeyer EM, Schultze-Lutter F. Diagnosing schizophrenia in the initial prodromal phase. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(2):158–164. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J, Picker H, Steinmeyer E, Ruhrmann S. Predicting first-episode psychosis by basic symptoms criteria. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4(1):11–22. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bechdolf A, Wagner M, Ruhrmann S, Harrigan S, Veith V, Pukrop R, Brockhaus-Dumke A, Berning J, Janssen B, Decker P, Bottlender R, Maurer K, Moller H, Gaebel W, Hafner H, Maier W, Klosterkotter J. Preventing progression to first-episode psychosis in early initial prodromal states. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(1):22–29. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.066357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ziermans TB, Schothorst PF, Sprong M, van Engeland H. Transition and remission in adolescents at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1-3):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schultze-Lutter F, Addington J, Ruhrmann S, Klosterkötter J. Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, Adult Version (SPI-A) Rome, Italy: Giovanni Fiorito Editore; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schultze-Lutter F, Marshall M, Koch E. Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, Child and Youth Version (SPI-CY), Extended English Translation. Rome, Italy: Giovanni Fiorito Editore; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keshavan MS, DeLisi LE, Seidman LJ. Early and broadly defined psychosis risk mental states. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1-3):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klosterkötter J, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, Ruhrmann S. Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next? World Psychiatry. 2011;10(3):165–174. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Valmaggia L. Heterogeneity in the assessment of the at-risk mental state for psychosis [letter] Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(7):813. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nelson B, Fusar-Poli P, Yung AR. Can we detect psychotic-like experiences in the general population? Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):376–385. doi: 10.2174/138161212799316136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ochoa S, Haro JM, Torres JV, Pinto-Meza A, Palacín C, Bernal M, Brugha T, Prat B, Usall J, Alonso J, Autonell J. What is the relative importance of self reported psychotic symptoms in epidemiological studies? results from the ESEMeD-Catalonia Study. Schizophr Res. 2008;102(1-3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Granö N, Karjalainen M, Itkonen A, Anto J, Edlund V, Heinimaa M, Roine M. Differential results between self-report and interview-based ratings of risk symptoms of psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5(4):309–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39(2):179–195. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schimmelmann B, Walger P, Schultze-Lutter F. The significance of at-risk symptoms of psychosis in children and adolescents. Can J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800107. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schimmelmann BG, Michel C, Schaffner N, Schultze-Lutter F. What percentage of people in the general population satisfies the current clinical at-risk criteria of psychosis? Schizophr Res. 2011;125(1):99–100. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kelleher I, Murtagh A, Molloy C, Roddy S, Clarke MC, Harley M, Cannon M. Identification and characterization of prodromal risk syndromes in young adolescents in the community: a population-based clinical interview study. Schizophr Bull. 2011;38(2):239–246. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yung AR, Nelson B, Thompson A, Wood SJ. The psychosis threshold in Ultra High Risk (prodromal) research: is it valid? Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yung AR, Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, McFarlane CA, Francey S, Harrigan S, Patton GC, Jackson HJ. Prediction of psychosis: a step towards indicated prevention of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;172(33):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, Woods SW, Addington J, Walker E, Seidman LJ, Perkins D, Tsuang M, McGlashan T, Heinssen R. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, Borgwardt S, Kempton M, Barale F, Caverzasi E, McGuire P. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fusar-Poli P, Bechdolf A, Taylor MJ, Bonoldi I, Carpenter WT, Yung AR, McGuire P. At risk for schizophrenic or affective psychoses? a meta-analysis of DSM/ICD diagnostic outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Schizophr Bull. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs060. published online May 15, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yung AR, Stanford C, Cosgrave E, Killackey E, Phillips L, Nelson B, McGorry PD. Testing the Ultra High Risk (prodromal) criteria for the prediction of psychosis in a clinical sample of young people. Schizophr Res. 2006;84(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Simon AE, Velthorst E, Nieman DH, Linszen D, Umbricht D, de Haan L. Ultra high-risk state for psychosis and non-transition: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2011;132(1):8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Addington J, Cornblatt BA, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Heinssen R. At clinical high risk for psychosis: outcome for nonconverters. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):800–805. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J, Maier W, Klosterkötter J. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):182–191. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yung A, Nelson B, Yuen H, Spiliotacopoulos D, Lin A, Simmonds HA, Bruxner A, Broussard C, Thompson A, McGorry P. Long term outcome in an ultra high risk (“prodromal”) group. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:22–23. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yung AR, Nelson B, Stanford C, Simmons MB, Cosgrave EM, Killackey E, Phillips LJ, Bechdolf A, Buckby J, McGorry PD. Validation of “prodromal” criteria to detect individuals at ultra high risk of psychosis: 2 year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2008;105(1-3):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Woods SW, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt BA, Heinssen R, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, McGlashan TH. Validity of the prodromal risk syndrome for first psychosis: findings from the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(5):894–908. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bechdolf A, Pukrop R, Köhn D, Tschinkel S, Veith V, Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Geyer C, Pohlmann B, Klosterkötter J. Subjective quality of life in subjects at risk for a first episode of psychosis: a comparison with first episode schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(1):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Addington J, Penn D, Woods SW, Addington D, Perkins DO. Social functioning in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2008;99(1-3):119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lencz T, Smith CW, Auther A, Correll CU, Cornblatt B. Nonspecific and attenuated negative symptoms in patients at clinical high-risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(1):37–48. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Velthorst E, Nieman DH, Linszen D, Becker H, de Haan L, Dingemans PM, Birch-wood M, Patterson P, Salokangas RK, Heinimaa M, Heinz A, Juckel G, von Reventlow HG, French P, Stevens H, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J, Ruhrmann S. Disability in people clinically at high risk of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(4):278–284. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Seidman LJ, Giuliano AJ, Meyer EC, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Bearden CE, Christensen BK, Hawkins K, Heaton R, Keefe RS, Heinssen R, Cornblatt BA North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS) Group. Neuropsychology of the prodrome to psychosis in the NAPLS consortium: relationship to family history and conversion to psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):578–588. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fusar-Poli P, Byrne M, Valmaggia L, Day F, Tabraham P, Johns L, McGuire P. Social dysfunction predicts two years clinical outcome in people at ultra high risk for psychosis. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cornblatt BA, Carrión RE, Addington J, Seidman L, Walker EF, Cannon TD, Cadenhead KS, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Tsuang MT, Woods SW, Heinssen R, Lencz T. Risk factors for psychosis: impaired social and role functioning. Schizophr Bull. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr136. published online November 10, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ruhrmann S, Paruch J, Bechdolf A, Pukrop R, Wagner M, Berning J, Schultze-Lutter F, Janssen B, Gaebel W, Möller HJ, Maier W, Klosterkötter J. Reduced subjective quality of life in persons at risk for psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(5):357–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hutton P, Bowe S, Parker S, Ford S. Prevalence of suicide risk factors in people at ultra-high risk of developing psychosis: a service audit. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5(4):375–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fusar-Poli P, Deste G, Smieskova R, Barlati G, Yung AR, Howes O, Stieglitz R, McGuire P, Borgwardt S. Cognitive functioning in prodromal psychosis: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(6):1–10. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Woodberry KA, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ. Premorbid IQ in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(5):579–587. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Giuliano AJ, Li H, Mesholam-Gately RI, Sorenson SM, Woodberry KA, Seidman LJ. Neurocognition in the psychosis risk syndrome: a quantitative and qualitative review. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):399–415. doi: 10.2174/138161212799316019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lin A, Wood SJ, Nelson B, Brewer WJ, Spiliotacopoulos D, Bruxner A, Broussard C, Pantelis C, Yung AR. Neurocognitive predictors of functional outcome two to 13 years after identification as ultra-high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2011;132(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Niendam TA, Jalbrzikowski M, Bearden CE. Exploring predictors of outcome in the psychosis prodrome: implications for early identification and intervention. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19(3):280–293. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9108-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Carrión RE, Goldberg TE, McLaughlin D, Auther AM, Correll CU, Cornblatt BA. Impact of neurocognition on social and role functioning in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):806–813. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]