Abstract

Background

Although critics have expressed concerns about cancer center advertising, the content of these advertisements has not been analyzed.

Objective

To characterize the informational and emotional content of cancer center advertisements.

Design

Systematic analysis of all cancer center advertisements in top U.S. consumer magazines (N=269) and television networks (N=44) in 2012.

Measurements

Using a standardized codebook, we assessed (1) types of clinical services promoted; (2) information provided about clinical services, including risks, benefits, and costs; (3) use of emotional advertising appeals; and (4) use of patient testimonials. Two investigators independently coded advertisements using ATLAS.ti. Kappa values ranged from 0.77 to 1.0.

Results

A total of 102 cancer centers placed 409 unique clinical advertisements in top media markets in 2012. Advertisements promoted treatments (88%) more often than screening (18%) or supportive services (13%; p<0.001). Benefits of advertised therapies were described more often than risks (27% vs. 2%; p<0.001) but rarely quantified (2%). Few advertisements mentioned insurance coverage or costs (5%). Emotional appeals were frequent (85%), most often evoking hope for survival (61%), describing cancer treatment as a fight or battle (41%), and evoking fear (30%). Nearly half of advertisements included patient testimonials, usually focused on survival or cure. Testimonials rarely included disclaimers (15%) and never described the results a typical patient might expect.

Limitations

Internet advertisements were not included.

Conclusions

Clinical advertisements by cancer centers frequently promote cancer therapy using emotional appeals that evoke hope and fear while rarely providing information about risks, benefits, or costs. Further work is needed to understand how these advertisements influence patient understanding and expectations of benefit from cancer treatments.

INTRODUCTION

Demand for cancer care is increasing rapidly in the United States (1–3). More than 1.6 million new cases of cancer are diagnosed each year, and an aging population is expected to contribute to a 45% increase in cancer incidence by 2030 (1). Advances in diagnostic and treatment modalities, coupled with increasing competition in the cancer care market, mean a growing number of patients with cancer face a dizzying array of therapeutic options. In 2012, a total of 1,513 cancer programs were accredited by the American College of Surgeons, and this number continues to grow annually (4).

Increasingly, cancer centers in the United States market their clinical services directly to the public through advertising (5,6). A recent survey of 348 cancer patients reported that 86% were aware of cancer-related advertisements, particularly for products and services related to their cancer types (7). The ethical implications of such advertising have been subject to prior debate (8). Proponents argue that healthcare advertising provides valuable information to the public about screening and treatment options, thereby furthering patient-centered care (9). Critics express concerns that healthcare advertising may exaggerate therapeutic benefits and drive inappropriate demands for clinical services, contributing to rapidly escalating health care costs (10–12). These concerns may be particularly heightened for cancer centers, because patients with advanced malignancies often overestimate the potential benefits they will receive from new treatments and/or their chance for cure (13–24). Misleading, emotionally-charged, or incomplete promotional claims in cancer center advertisements may contribute to widespread misperceptions about cancer care.

To date, however, there has been no empirical examination of the content of cancer center advertisements. An understanding of advertising content is necessary to inform future investigations of advertising impact. We therefore conducted a systematic content analysis of cancer center advertisements for clinical services. Our aim was to describe the types of clinical services promoted, the amount of information provided about these services, and the use of emotional advertising appeals and patient testimonials. We further sought to describe whether informational and emotional advertising content differed by type of cancer center.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic content analysis of all cancer center advertisements for clinical services in top consumer magazines and on television networks in the United States in 2012. We chose to examine magazine and television advertisements because cancer patients report being most frequently aware of advertising in these media markets (7).

Data Sources

We obtained all advertisements from Kantar Media, an independent media-monitoring agency that tracks and electronically archives local and national advertisements in the top 269 U.S. consumer magazines and on 44 television networks (total audience of 115,810,740 in 2012). Kantar Media provided full content (in JPEG format for magazine advertisements and in Audio Video Interleaved (AVI) format for television advertisements) for every cancer center advertisement in 2012.

We additionally collected information about cancer centers to characterize our study sample: 1) National Cancer Institute (NCI) designation status (obtained from the NCI website (25)), 2) Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation status (obtained from the American College of Surgeons website (26)), 3) tax-exemption status (verified by calling the number listed on each cancer center’s website), and 4) number of facilities per center and regional location (obtained from each cancer center’s website).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included unique cancer center advertisements for clinical services in 2012. Duplicate advertisements, advertisements related to cancer but not promoting a cancer center (e.g., Susan G. Komen for the Cure Foundation), and advertisements that were not in English or for which the full-length content was not available were excluded. Upon full content review of remaining advertisements, we further excluded advertisements that were public service announcements only, included only the cancer center name, image or slogan without a description of clinical services, included only a provider profile without a description of clinical services, or described fundraising, employment, or research opportunities only.

Codebook Development

Our multidisciplinary team developed a standardized codebook to categorize advertising content. We developed all coding categories a priori based on content analyses of healthcare advertisements in other contexts (27–29) and advertising principles from the marketing field (30). Our codebook encompassed 4 domains: (1) types of clinical services promoted, (2) information provided about advertised services, (3) use of emotional advertising appeals, and (4) use of patient testimonials and disclaimers.

We categorized types of advertised services as 1) cancer treatments (including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgical interventions), 2) cancer screening (e.g., mammography or colonoscopy) or 3) supportive services (including nutritional services, complementary and alternative therapies, spiritual services, psychosocial services, physical or occupational therapy, and palliative care). Within each category, we also coded whether the type of clinical service was specified (e.g., “Novac7 Intraoperative Radiation Therapy”) or unspecified (e.g., “a combination of complex therapies”).

We assessed whether information was provided about the indication (cancer type and stage), benefits (any description of a potential positive outcome), risks (any description of a potential negative outcome), alternatives, and costs of advertised services. We further categorized information about benefits and risks as qualitative (e.g., “CyberKnife targets and destroys tumors throughout the body.”) or quantitative (“If [breast cancer] is caught early, 98% will survive 5 years.”). We designated any text that mentioned the cost of services or potential insurance coverage as a description of cost (e.g., “In-network with most tri-state area health plans.”).

We coded for emotional appeals related to (1) survival or potential for cure and (2) comfort, quality of life or patient-centered care. We created sub-codes within each category to further classify persuasive advertising techniques that have been described in other contexts (27,28,30). For example, related to survival or potential for cure we specifically assessed for descriptions of (1) hope, survival, or cure; (2) death, disability, or fear; (3) advanced technology; (4) fighting cancer; (5) relentless cancer care; and (6) medical miracles. Related to comfort, quality of life and patient-centered care, we specifically assessed for descriptions of (1) individualized care; (2) comfort, compassion, symptom management, or quality of life; and (3) involving patients and families in decision making.

We defined a patient testimonial as any endorsement of the cancer center by a named patient, including local or national celebrities. For advertisements including patient testimonials, we assessed whether a disclaimer was included (defined as any mention of whether results were typical or whether viewers may expect to see similar results). Finally, if a disclaimer was present, we assessed whether a description of typical results that a viewer might expect was included (31).

The complete codebook, including definitions and representative examples, is included in the appendix.

Coding and Statistical Analysis

Two coders independently coded all advertisements using ATLAS.ti 7, a qualitative data analysis software program with multimedia capability. All questions that arose during individual coding were brought to the team for discussion and resolution by consensus. To assess inter-rater reliability, both coders independently coded a subset of 20 advertisements (10 each magazine and television) and a kappa was calculated for each code. We used simple descriptive statistics (proportions and chi-squared tests) to summarize the data and to compare for differences in content between NCI-designated and non-NCI-designated cancer centers.

Role of the Funding Source

This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The source had no role in study design, conduct or analysis.

RESULTS

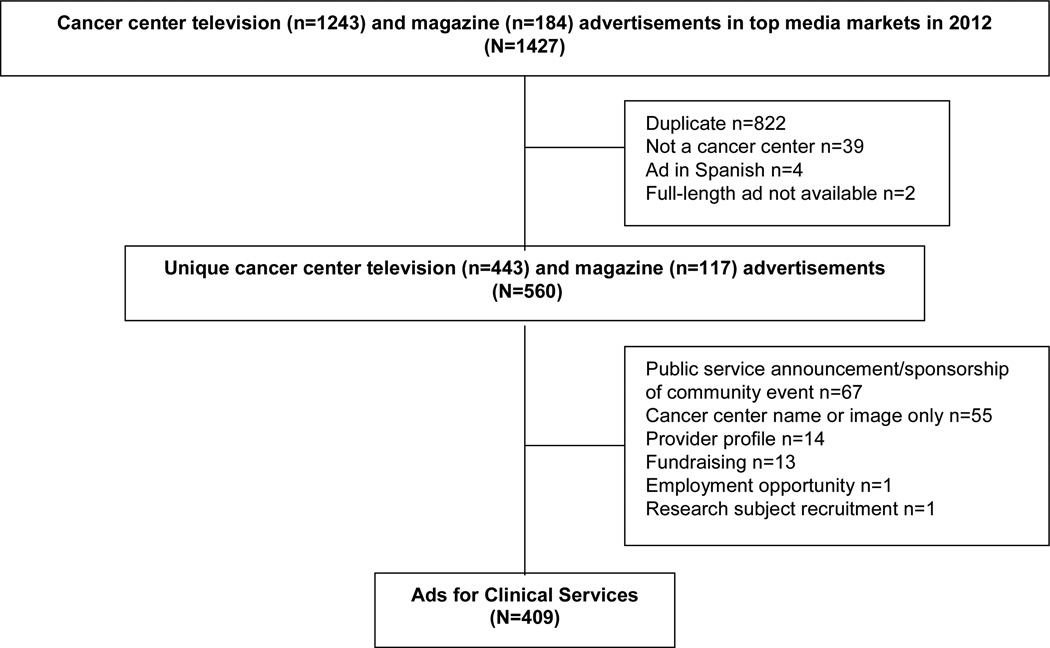

Of 1,427 advertisements placed between January 1 and December 31, 2012, 1,018 were excluded for the reasons identified in Figure 1, leaving 409 unique advertisements promoting clinical services at 102 cancer centers.

Figure 1.

Results of cancer center advertisement search

Eighty-seven cancer centers placed clinical advertisements on television, 28 cancer centers placed clinical advertisements in magazines, and 13 cancer centers advertised in both media markets. The mean number of unique magazine advertisements per institution was 3 (range 1–18) and the mean number of unique television advertisements per institution was 3.7 (range 1–45).

Characteristics of centers placing clinical advertisements are shown in Table 1. The majority were for-profit (60%) and 16% were NCI-designated.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cancer Centers Placing Clinical Advertisements (N=102)

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| For-profit | 60 (59) |

| NCI-designated | 16 (16) |

| Commission on Cancer-accredited | 60 (59) |

| Clinical Sites | |

| Single center | 47 (46) |

| Multi-center | 55 (54) |

| Number of sites, median | 2 (range: 1–135) |

| Region* | |

| Northeast | 19 (19) |

| Midwest | 32 (31) |

| South | 33 (32) |

| West | 21 (21) |

Total does not equal 100%. Some centers had locations in more than one region.

Coding of advertisements proceeded without difficulty. Kappa values for our main findings ranged from 0.77 to 1.0, indicating excellent inter-rater reliability.

Types of Clinical Services

The specific types of clinical services advertised are presented in Table 2. Advertisements most commonly promoted cancer treatments (359/409; 88%) rather than cancer screening (75/409; 18%) or supportive services (53/409; 13%; p<0.001). In half of the advertisements (203/409; 50%), the type of cancer treatment was not specified (e.g., “The most advanced and accurate treatment options,” “Our team has saved lives through groundbreaking technology, personalized treatments, and research.”). Very few advertisements (8/409; 2%) mentioned palliative care or symptom management services.

Table 2.

Clinical Services Promoted by Cancer Centers

| Service | N (%) of 409 Advertisements* |

|---|---|

| Cancer Treatments | 359 (88) |

| Non-Specified Cancer Therapy (e.g., “We offer you our most aggressive treatment plan,” “a combination of complex therapies”) |

203 (50) |

| Radiation Therapy (e.g., “Brachytherapy,” “TomoTherapy,” “Cyberknife”) | 109 (27) |

| Surgical Intervention (e.g., “Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Prostatectomy”) | 63 (15) |

| Chemotherapy | 30 (7) |

| Other or Combined Cancer Therapy (e.g., “Novac7 Intraoperative Radiation Therapy”) |

29 (7) |

| Cancer Screening Services | 75 (18) |

| Cancer Screening or Imaging (e.g., “PET/CT Scan,” “3DCT,” “ductoscopy”) | 75 (18) |

| Supportive Services | 53 (13) |

| Nutritional Services (e.g., “We help cancer patients maintain nutritional diets”) | 23 (6) |

| Complementary and Alternative Medicine (e.g., “acupuncture,” “Yoga”) | 20 (5) |

| Spiritual or Religious Services (e.g., “daily interfaith worship services”) | 16 (4) |

| Psychosocial Services (e.g., “psychological counseling”) | 10 (2) |

| Physical or Occupational Therapy (e.g., “rehabilitation”) | 8 (2) |

| Supportive/Palliative Care (e.g., “pain management”) | 8 (2) |

| Non-Specified Supportive Services (e.g., “a number of supportive services”) | 18 (4) |

Total does not equal 100%. Individual advertisements may promote multiple types of clinical services.

Information about Clinical Services

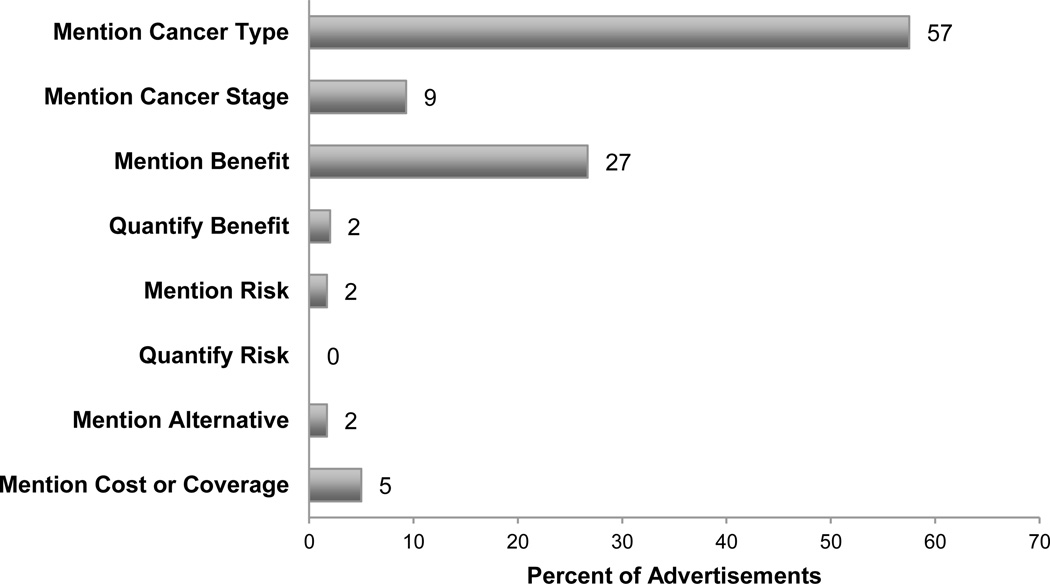

Information provided about clinical services is shown in Figure 2. Fifty-seven percent (235/409) of advertisements indicated a specific type of cancer (e.g., “devoted exclusively to women fighting breast cancer”), whereas only 9% (38/409) indicated the stage of cancer (e.g., “complex and late-stage cancer”) targeted by advertised therapies. Less than 2% (7/409) of advertisements mentioned an alternative to the advertised service (e.g., “CyberKnife may be an alternative to surgery,” “Breast brachytherapy is a 5-day alternative to 6 weeks of radiation.”). Over 25% (109/409) of advertisements mentioned potential benefits of advertised therapies (“the da Vinci System offers a shorter hospital stay and less chance of needing follow-up surgery.”), but only 2% (8/409) quantified these benefits. Less than 2% (7/409) of advertisements mentioned the possibility of risks from treatment (e.g., “a low risk of incontinence and impotence”), and no advertisements quantified the level of potential risks. Only 5% (21/409) of advertisements mentioned cost or coverage of advertised treatments.

Figure 2.

Proportion of 409 advertisements promoting clinical services that mention benefits, risks, indications, alternatives, and costs

Emotional Appeals

Eighty-five percent (347/409) of advertisements included emotional appeals (see Table 3). Emotional appeals more commonly related to survival or potential for cure (347/409, 85%) rather than comfort, quality of life, or patient-centered care (177/409; 43%; p<0.001).

Table 3.

Types of Emotional Appeals Used In Cancer Center Advertisements

| Persuasion Technique | Illustrative Examples | N (%) of 409 advertisements* |

|---|---|---|

| Focus on Survival or Potential for Cure | ||

| Evoke Hope for Survival | Uses language about hope, life, survival, extension of life, or cure (“Call us today to begin your journey from cancer patient to cancer survivor.”) |

248 (61) |

| Focus on Innovation or Treatment Advances |

Describes technology, treatment, or research that is innovative, pioneering, advanced, or upcoming (“We use state-of-the-art technology and give you innovative treatment options.”) |

211 (52) |

| Use Fighting Language | Describes cancer as a fight or battle (“Winning the war against cancer,” “I can kick this,” “I fought, I won.”) |

167 (41) |

| Evoke Fear | Mentions death, disability, fear, or loss (“When David was diagnosed with cancer in his chest, he felt like he was losing everything.”) |

123 (30) |

| Unrelenting Care | Describes treatment that does not stop until cancer is cured or cancer in general is no more (“Making history,” “Care that never quits.”) |

78 (19) |

| Medical Miracles | Describes cancer treatment or center as miraculous, remarkable, or extraordinary (“Extraordinary results.”) |

78 (5) |

| Focus on Comfort, Quality of Life, or Patient-Centered Care | ||

| Individualized Care | States that treatment or experience will be tailored to meet patients’ needs (“I’m remembered by my name, not as a number,” “Our patients are unique. So are their tumors.”) |

127 (31) |

| Highlight Comfort or Describe Quality of Life |

Mentions comfort, compassion, symptom management, or quality of life (“We’re dedicated to not only providing the best treatment, but the best quality of life at every turn.”) |

106 (26) |

| Shared Decision Making | Discusses involvement of patients or family members in medical decision making (“They offered me advice about treatments, but the decision was always mine.”) |

25 (6) |

Total does not equal 100%. Individual advertisements may be coded for multiple persuasion techniques.

Sixty-one percent (248/409) of advertisements used language that evoked hope (e.g., “Your last hope,” “Our advanced care adds another dimension to cancer care. Hope.”). More than 40% (167/409) of advertisements described cancer as a fight or battle (e.g., “Knocking out cancer,” “I fought, I won.”), 30% (123/409) evoked fear (e.g., “I didn’t know if anyone survived pancreatic cancer.”), and 19% suggested unrelenting care (e.g., “Care that never quits.”). More than half of advertisements (211/409) mentioned technological innovations or treatment advances (e.g., “Introducing TomoTherapy, the most advanced treatment available.”) and 6% (24/409) evoked medical miracles (e.g., “Beyond extraordinary.”).

Less than one-third (106/409) of advertisements highlighted patient comfort, compassion, symptom management, or quality of life (e.g., “We provide options to make the treatment time more comfortable.”, “We’re dedicated to not only providing the best treatment, but the best quality of life at every turn.”). Thirty-one percent of advertisements (127/409) mentioned that the treatment or experience would be tailored to meet patients’ needs (e.g., “Personalized care in a comfortable environment”, “Our patients are unique. So are their tumors.”). Six percent (25/409) of advertisements discussed involvement of patients or family members in medical decision making (e.g., “I was part of the decision-making team”, “They offered me advice about treatments, but the decision was always mine.”).

Testimonials

Nearly half (181/409; 44%) of advertisements for clinical services included endorsements from cancer patients; a small minority (21/409; 5%) included endorsements from local or national celebrities. Testimonials overwhelmingly focused on stories about survival or cure (143/181; 79%); for example, “I used to think that you had to go to NYC for anything serious, but after my experience, I don’t know why anyone would go anywhere but the Littman Cancer Center. They saved my life.”, “My doctor back home gave me ONLY a few weeks to live. That’s when I made the ONE decision that saved my life. I went to MD Anderson. That was seven years ago. And counting.” Only 15% (27/181) included a disclaimer (e.g., “Most patients do not experience these results.”). No advertisements described the outcome a typical patient might expect.

Comparison of Advertising Content by Cancer Center Type

Comparison of advertising content by NCI cancer center designation is shown in Table 4. Advertisements placed by NCI-designated cancer centers were less likely than advertisements placed by non-NCI designated cancer centers to promote cancer treatments (p=0.019) or supportive services (p=0.031). Description of risks, benefits and alternatives occurred with similar frequency. However, NCI-designated advertisements were more likely to mention costs or coverage of services (p=0.003) and less likely to indicate a specific type of cancer (p=0.006). Testimonials and emotional appeals related to survival were observed with greater frequency among NCI-designated center advertisements (p<0.001; p=0.041).

DISCUSSION

In a systemic content analysis of 409 advertisements for clinical services placed by 102 cancer centers in the United States in 2012, we found that cancer therapies were promoted more commonly than supportive or screening services and often described in vague or general terms. Advertisements commonly evoked hope for survival, promoted innovative treatment advances, and used language about fighting cancer, while providing relatively limited information about benefits, risks, or costs of advertised therapies. Patient testimonials focused on survival and rarely included disclaimers.

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive analysis of cancer center advertising content. However, our findings are consistent with a prior analysis of advertising among top U.S. hospitals, which also found frequent use of emotional appeals and scarce mention of risk of services or quantification of benefit (27). Our sample included both for-profit and non-profit cancer centers, as well as a significant percentage of cancer centers with more prominent credentials (approximately 5 percent of cancer centers nationally are NCI-designated, whereas 16% of centers placing clinical advertisements in 2012 had this designation). Interestingly, we found that NCI-designated centers more frequently used emotional appeals related to survival or potential for cure. Although these centers mentioned cost or coverage of treatment more commonly, they omitted information about risks, benefits and alternatives with similar frequency as non NCI-designated centers. These findings suggest that emotional appeals coupled with incomplete information are being widely used to promote services, even among the nation’s most prestigious cancer centers.

The use of emotion can be an effective and powerful means of persuasion (32). Information-based strategies present viewers with evidence (such as benefits, risks, and/or costs of products or services) and persuade by the force of logic. In contrast, emotional appeals persuade viewers by creating feelings of empathy for the characters or by associating the brand with feelings of warmth and hope (33). Fear appeals persuade an audience by presenting negative consequences (e.g., progression of cancer or death) and by subsequently providing a solution to the undesirable outcome (e.g., receiving cancer treatment at a specific location) (30,34,35). The use of emotional appeals has several persuasive advantages over reasoning strategies: it does not raise consumers’ normal defenses, it requires less effort from the viewer, and it increases viewer recall of advertised products and/or services (32,36,37). Research has shown that highly emotional advertisements have been more effective in changing behavior for cancer screening and smoking cessation when compared with low-emotion or logic-based advertisements (38,39). Emotional appeals have also been used to advertise genetic tests, self-referred imaging services, and prescription medications (40–42).

Given the inherently frightening nature of cancer, it may be impossible for cancer centers to advertise without arousing viewers’ emotions to some degree. However, clinical advertisements that use emotional appeal uncoupled from information about indications, benefits, risks, or alternatives may lead patients to pursue care that is either unnecessary or unsupported by scientific evidence. Pursuit of unnecessary tests and/or treatment may, in turn, expose patients to avoidable risks and contribute to rising costs for patients and the healthcare system (43). Further research is needed to identify the extent (if any) to which cancer center advertising contributes to rapidly escalating costs of cancer care in the United States.

Finally, the dominant narrative of survival in cancer center advertising must be considered in light of well-described overestimations of curability and treatment benefit among patients with cancer (13–24). While efforts to explain patients’ false hope have traditionally focused on psychological needs and/or inadequate communication with physicians (44–46), advertising testimonials about potential cure may also play a role. To the extent that such advertisements generate inaccurate expectations of treatment benefit, they may complicate provider-patient discussions about prognosis and appropriate therapeutic options. While the Federal Trade Commission recently mandated that testimonials include disclaimers and a description of results that a typical patient may expect to see (31), we found only limited evidence of this practice.

Our study has several limitations. First, we analyzed magazine and television advertisements only. Our findings may not generalize to cancer center advertisements in other types of media such as the Internet, newspapers, radio, or billboards. Second, we obtained advertising content from a media-monitoring agency that tracks advertisements based on the advertiser, content, and date. While healthcare researchers commonly use this search strategy (27,47,48), it is possible that advertisements meeting our inclusion criteria were not obtained. Third, as with other content analyses, our assessment of advertisements involved creating codes to classify data. We attempted to maximize objectivity by developing an extensive codebook with definitions and examples informed by previously defined advertising techniques, and our kappa calculation demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability. Finally, the nature of this analysis did not allow us to directly examine the effect of advertising content on patients.

In summary, we found that clinical advertising by cancer centers frequently promoted cancer therapy using emotional appeals that evoked hope and fear while providing relatively little substantive information about risks, benefits, indications, or costs. Further work is needed to understand how cancer center advertisements influence viewer preferences and patients’ expectations of benefit from cancer treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sara Einhorn for her assistance with coding and Greer Tiver for her assistance with ATLAS.ti.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number KL2TR000146. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Schenker was additionally supported by the Junior Scholar Award from the University of Pittsburgh, Department of Medicine.

Footnotes

This is the prepublication, author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in Annals of Internal Medicine. This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The American College of Physicians, the publisher of Annals of Internal Medicine, is not responsible for the content or presentation of the author-produced accepted version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to this manuscript (e.g., correspondence, corrections, editorials, linked articles) should go to Annals.org or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.

References

- 1.National Research Council. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren JL, Yabroff KR, Meekins A, Topor M, Lamont EB, Brown ML. Evaluation of trends in the cost of initial cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:888–897. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Surgeons [internet] [cited 2014 Jan 29];About Accreditation. updated 2013 Feb 27; Available from: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/whatis.html.

- 5.Newman AA. A Healing Touch From Hospitals. The New York Times; 2011. Sep 13, Sect. B: 2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray SW, Abel GA. Update on Direct-to-Consumer Marketing in Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:124–127. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abel GA, Burstein HJ, Hevelone ND, Weeks JC. Cancer-related direct-to-consumer advertising: awareness, perceptions, and reported impact among patients undergoing active cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4182–4187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schenker Y, Arnold RM, London AJ. The Ethics of Advertising for Healthcare Services. Am J Bioeth. 2014 doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.879943. [In press]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissman JS, Blumenthal D, Silk AJ, Newman M, Zapert K, Leitman R, et al. Physicians report on patient encounters involving direct-to-consumer advertising. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004:W4-219–W4-233. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, Franz CE, Azari R, Wilkes MS, et al. Influence of patients' requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1995–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singer N. Cancer Center Ads Use Emotion More Than Facts. The New York Times; 2009. Dec 18, Sect. A:1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lovett KM, Liang BA, Mackey TK. Risks of online direct-to-consumer tumor markers for cancer screening. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1411–1414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackillop WJ, Stewart WE, Ginsburg AD, Stewart SS. Cancer patients' perceptions of their disease and its treatment. Br J Cancer. 1988;58:355–358. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eidinger RN, Schapira DV. Cancer patients' insight into their treatment, prognosis, and unconventional therapies. Cancer. 1984;53:2736–2740. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840615)53:12<2736::aid-cncr2820531233>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pronzato P, Bertelli G, Losardo P, Landucci M. What do advanced cancer patients know of their disease? A report from Italy. Support Care Cancer. 1994;2:242–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00365729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravdin PM, Siminoff IA, Harvey JA. Survey of breast cancer patients concerning their knowledge and expectations of adjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:515–521. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sapir R, Catane R, Kaufman B, Isacson R, Segal A, Wein S, et al. Cancer patient expectations of and communication with oncologists and oncology nurses: the experience of an integrated oncology and palliative care service. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:458–463. doi: 10.1007/s005200000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chow E, Andersson L, Wong R, Vachon M, Hruby G, Frannsen E, et al. Patients with advanced cancer: a survey of the understanding of their illness and expectations from palliative radiotherapy for symptomatic metastases. Clin Oncol. 2001;13:204–208. doi: 10.1053/clon.2001.9255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SJ, Fairclough D, Antin JH, Weeks JC. Discrepancies between patient and physician estimates for the success of stem cell transplantation. JAMA. 2001;285:1034–1038. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns CM, Broom DH, Smith WT, Dear K, Craft PS. Fluctuating awareness of treatment goals among patients and their caregivers: a longitudinal study of a dynamic process. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:187–196. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, Lynch TJ, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitera G, Zhang L, Sahgal A, Barnes E, Tsao M, Danjoux C, et al. A survey of expectations and understanding of palliative radiotherapy from patients with advanced cancer. Clin Oncol. 2012;24:134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, Finkelman MD, Mack JW, Keating NL, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen AB, Cronin A, Weeks JC, Chrischilles EA, Malin J, Jayman JA, et al. Expectations about the effectiveness of radiation therapy among patients with incurable lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2730–2735. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Cancer Institute [internet] [cited 2013 July 24];NCI-Designated Cancer Centers. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/researchandfunding/extramural/cancercenters/find-a-cancer-center.

- 26.American College of Surgeons [internet] [cited 2014 Jan 29];Cancer Program Accreditation. updated 2011 Oct 18; Available from: http://www.facs.org/cancerprogram/index.html.

- 27.Larson RJ, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Welch HG. Advertising by academic medical centers. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:645–651. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abel GA, Lee SJ, Weeks JC. Direct-to-consumer advertising in oncology: a content analysis of print media. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1267–1271. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Wilkes MS. Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising, 1989–1998. A content analysis of conditions, targets, inducements, and appeals. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong JS. Persuasive Advertising: Evidence-based Principles. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Federal Trade Commission, 16 C.F.R. Part 255. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tellis GJ. Effective Advertising: Understanding When, How, and Why Advertising Works. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stern BB. Classical and Vignette Television Advertising Dramas: Structural Models, Formal Analysis and Consumer Effects. J Consum Res. 1994;20:601–615. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Algie J, Rossiter JR. Fear patterns: a new approach to designing road safety advertisements. J Prev Interv Community. 2010;38:264–279. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2010.509019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz IM. Hospitalization of adolescents for psychiatric and substance abuse treatment. Legal and ethical issues. J Adolesc Health Care. 1989;10:473–478. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(89)90009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ambler T, Burne T. The Impact of Affect on Memory of Advertising. J Advert Res. 1999;39:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunlop SM, Perez D, Cotter T. The natural history of antismoking advertising recall: the influence of broadcasting parameters, emotional intensity and executional features. Tob Control. 2012:1–8. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050256. 0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dillard JP, Nabi RL. The Persuasive Influence of Emotion in Cancer Prevention and Detection Messages. Journal of Communication. 2006;56:S123–S139. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunlop SM, Cotter T, Perez D. When your smoking is not just about you: antismoking advertising, interpersonal pressure, and quitting outcomes. J Health Commun. 2014;19:41–56. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.798375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parrott R, Volkman J, Ghetian C, Weiner J, Raup-Krieger J, Parrott J. Memorable messages about genes and health: implications for direct-to-consumer marketing of genetic tests and therapies. Health Mark Q. 2008;25:8–32. doi: 10.1080/07359680802126061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Illes J, Kann D, Karetsky K, Letourneau P, Raffin TA, Schraedley-Desmond P, et al. Advertising, patient decision making, and self-referral for computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2415–2419. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.22.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frosch DL, Krueger PM, Hornik RC, Cronholm PF, Barg FK. Creating demand for prescription drugs: a content analysis of television direct-to-consumer advertising. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:6–13. doi: 10.1370/afm.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volpp KG, Loewenstein G, Asch DA. Choosing wisely: low-value services, utilization, and patient cost sharing. JAMA. 2012;308:1635–1636. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The AM. Hak T, Koeter G, van Der Wal G. Collusion in doctor-patient communication about imminent death: an ethnographic study. BMJ. 2000;321:1376–1381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7273.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee Char SJ, Evans LR, Malvar GL, White DB. A randomized trial of two methods to disclose prognosis to surrogate decision makers in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:905–909. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0262OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gattellari M, Voigt KJ, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. When the treatment goal is not cure: are cancer patients equipped to make informed decisions? J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:503–513. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donohue JM, Cevasco M, Rosenthal MB. A decade of direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:673–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa070502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mehrotra A, Grier S, Dudley RA. The relationship between health plan advertising and market incentives: evidence of risk-selective behavior. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25:759–765. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.