Abstract

Little is known on the diversity and public health significance of Echinococcus species in livestock in Egypt. In this study, 37 individual hydatid cysts were collected from dromedary camels (n=28), sheep (n=7) and buffalos (n=2). DNA was extracted from protoscoleces/germinal layer of individual cysts and amplified by PCR targeting nuclear (actin II) and mitochondrial (COX1 and NAD1) genes. Direct sequencing of amplicons indicated the presence of Echinococcus canadenesis (G6 genotype) in 26 of 28 camel cysts, 3 of 7 sheep cysts and the 2 buffalo derived cysts. In contrast, Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto (G1 genotype) was detected in one cyst from a camel and 4 of 7 cysts from sheep, whereas Echinococcus ortleppi (G5 genotype) was detected in one cyst from a camel. This is the first identification of E. ortleppi in Egypt.

Introduction

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a cosmopolitan zoonotic disease caused by infection with the cestode Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato (s.l.). The domestic life cycle involves the ingestion of parasite eggs, derived from the final host (dogs and other canids), by an intermediate host belonging to a wide range of mammalian species including humans [1,2]. Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has included echinococcosis as part of a Neglected Zoonosis subgroup in its 2008–2015 strategic plans for the control of neglected tropical diseases [3]. The disease contributes to the poor overall development and work productivity in the endemic areas. CE remains highly endemic in pastoral communities, particularly in regions of South America, the Mediterranean littoral, Eastern Europe, East Africa, the Near and Middle East, Central Asia, China and Russia, with several millions of humans infected [4,5]. It is responsible for approximately 1% admissions to surgical wards in some countries such as Iran [6]. It is estimated that CE results in annual economic losses of several billion dollars in livestock sector due to low performance, morbidity and/or mortality of infected animals, and condemnation of infected organs of slaughtered animals [7].

Based on the biological and molecular studies, E. granulosus s.l. comprises a number of forms that differ substantially in infectivity, host range and genetic characteristics [2]. At least 10 strains (G1–10) of E. granulosus s.l. have been described [8], forming 4 major clades (G1–3, G4, G5, G6–G10) [9,10]. Recent re-evaluations of Echinococcus species strongly suggests that the genotypes G1 to G5 should be reclassified as E. granulosus sensu stricto (s.s.; G1 to G3), E. equinus (G4), and E. ortleppi (G5) [11]. There is also strong support for species status of genotypes G6 to G10 (E. canadensis) and the lion strain (E. felidis). This extensive biologic variation in E. granulosus may influence lifecycle patterns, pathology, antigenicity, transmission dynamics, and sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents. For example, E. canadensis G6–G7, E. equinus, E. granulosus s.s., and E. ortleppi are transmitted mainly through domestic cycles [12]. The diagnosis of Echinococcus species involved might therefore have implications for the design and development of prevention and control measures, diagnostic assays, and drugs [13,14].

In Middle East and Africa, CE is a significant public health problem with high endemicity in the Arabic North Africa [15]. A considerable body of molecular data on E. granulosus s.l. from various intermediate and definitive hosts in African countries has indicated the prevalence of G1 strain (E. granulosus s.s.) and G6 strain (E. canadensis) in this area of the world [16–19]. Thus far, studies from Egypt are mostly phenotypic investigations [20,21], with few data available on genetic identity of the parasite. Among the few molecular studies, two [22,23] used RAPD banding patterns in characterizing hydatid cysts from several hosts and two [24,25] used PCR-sequence analysis of mitochondrial markers on cysts from a few hosts.

The present study was conducted to extend the knowledge on the identity of E. granulosus s.l. cysts collected from a range of livestock (camels, sheep, and buffalos) in Egypt. To this end, hydatid cysts were characterized by PCR-sequence analysis of the partial nuclear gene actin II and mitochondrial genes cytochrome C oxidase subunit 1 (COX1) and NADH dehydrogenase 1 (NAD1).

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Committee of the Post-graduate Studies and Research at Kafr El Sheikh University, Egypt. Hydatid cysts were collected from slaughtered animals during post-mortem inspection by veterinary officers at the Al Basatein Abattoir, Cairo, Egypt, during April-October, 2011. Formal consent and permission for research use of hydatid cysts were obtained from both the university and abattoir veterinarians. No experiment was conducted on live animals.

Cyst collection

A total of 37 hydatid cysts were collected from dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius; n = 28), sheep (Ovis aries; n = 7) and buffalos (Bubalus bubalis; n = 2). All camel derived cysts except for 2 (from the liver) were collected from the lung, whereas all sheep and buffalo derived cysts were collected from the liver. To confirm the potential genetic diversity, only one cyst was collected from each animal. Individual cysts were placed in sterile saline solution in numbered plastic cups and transported within 6 hours to the laboratory in ice box. To evaluate the cyst fertility, cyst contents were aseptically aspirated, transferred into sterile Petri dishes, and examined for the presence of protoscoleces (fertile cysts). Protoscoleces were collected from individual fertile cysts, whereas germinal layer was collected from individual infertile cysts under aseptic conditions. Collected materials were washed three times with sterile saline solution and fixed in 95% ethanol.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Materials from individual cysts were washed off ethanol with distilled water by centrifugation. DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Maryland, USA), following manufacturer-recommended procedures. A 266-bp fragment of the nuclear gene actin II was amplified using the primers described by Da Silva et al. [26], and 396- and 488-bp fragments of mitochondrial genes COX1 and NAD1, respectively, were amplified using the primers by Bart et al. [27]. PCR was done in 50 μl reaction mixture consisted of 1 × GeneAmp PCR buffer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 200 μM of dNTP (Promega, Madison, WI), 3 mM MgCl2, 260 nM primers and 1.5 units of GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promaga). PCR cycles consisted of denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 56°C (for NAD1) or 60°C (for actin II and COX1) for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for 50 s; and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were analyzed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

DNA sequence analysis

PCR products were sequenced directly using the Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were assembled using the ChromasPro (version 1.5) software (http://technelysium.com.au/?page_id=27). The accuracy of data was confirmed by bi-directional sequencing. The obtained sequences were aligned with each other and reference sequences using ClustalX (http://www.clustal.org/) to determine the genotype of Echinococcus isolates. Unique nucleotide sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AB921019 to AB921053 for actin II sequences, AB921054 to AB921090 for COX1 sequences, and AB921091 to AB921125 for NAD1 sequences.

Phylogenetic analysis

In the present study, the haplotype approach described by Abushhewa et al. [16] was adopted to infer phylogeny, using the Bayesian analysis implemented in MrBayes software (version 3.2.2) (http://mrbayes.sourceforge.net/) and the Metropolis Coupled Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMCMC) method to estimate posterior distribution of parameters. Haplotype segregation in the generated sequences was determined using the TCS (version 1.21) software (http://darwin.uvigo.es/software/tcs.html). Reference sequences were compiled from previous studies (Table 1), with Taenia saginata as an outgroup. Nexus files of aligned COX1 and NAD1 gene fragment sequences were created using ClustalX [29], while aligned matrices of COX1 and NAD1 were concatenated using Mesquite software (http://mesquiteproject.org) In MrBayes, the model of sequence evolution was specified with two substitution types (nst = 2), transitions and transversions, for analysis of the input data matrix. The 50% majority rule consensus tree generated was viewed and printed using the Mesquite program.

Table 1. GenBank accession numbers of COX1 and NAD1 of Echinococcus species/ genotypes/haplotype used in phylogenetic analysis in the present study.

| Parasite species/genotype/haplotype | Host origin | Locality | Accession No. for COX1 | Accession No. for NAD1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotype 1 (G1)* | Camel | Egypt | AB921054 | AB921091 |

| Haplotype 2 (G1)* | Sheep | Egypt | AB921090 | AB921125 |

| Haplotype 3 (G5)* | Camel | Egypt | AB921055 | AB921092 |

| Haplotype 4 (G6)* | Camel | Egypt | AB921058 | AB921095 |

| Haplotype 5 (G6)* | Camel | Egypt | AB921068 | AB921105 |

| Haplotype 6 (G6)* | Camel | Egypt | AB921075 | AB921111 |

| Haplotype 7 (G6)* | Camel | Egypt | AB921083 | AB921119 |

| Haplotype 8 (G6)* | Camel | Egypt | AB921084 | AB921120 |

| Haplotype 9 (G6)* | Camel | Egypt | AB921085 | AB921121 |

| G1–3 | Cattle | Libya | HM636639 | HM636643 |

| G1–3 (G1) | Cattle | Libya | HM636641 | HM636644 |

| G1–3 (G1) | Cattle, camel | Iran | FJ796205 | FJ796208 |

| G1–3 (G1) | Human, Cattle | Turkey | HQ717150 | HQ717151 |

| G1–3 (G1) | Human | Turkey | HQ717148 | HQ717153 |

| G1 | Human | Iran | KF612390 | KF612360 |

| G1 | Human | Iran | KF612376 | KF612349 |

| G1 | Sheep | Greece | DQ856467 | DQ856470 |

| G1 | Sheep | United Kingdom | AF297617 | AF297617 |

| G2 | Sheep | Australia | M84662 | AJ237633 |

| G1–3 (G3) | Camel | Iran | FJ796206 | FJ796214 |

| G3 | Buffalo | India | M84663 | AJ237634 |

| G3 | Human | Iran | KF612397 | KF612369 |

| G3 | Sheep | Greece | DQ856466 | DQ856469 |

| G4 | Horse | India | M84664 | AJ237635 |

| G5 | Cattle | Netherlands | M84665 | AJ237636 |

| G6–10 (G6) | Camel | Iran | FJ796207 | FJ796216 |

| G6 | Camel | Africa | M84666 | AJ237637 |

| G6 | Cattle, camel | Libya | HM636638 | HM636642 |

| G6 | Human | Iran | KF612400 | KF612372 |

| G6 | Camel | Kazakhstan | NC_011121 | NC_011121 |

| G6–10 (G7) | Human | Turkey | HQ717155 | HQ717154 |

| G7 | Goat | Greece | DQ856468 | DQ856471 |

| G7 | Pig | Poland | M84667 | AJ237638 |

| G8 | Moose | USA | AB235848 | AJ237643 |

| G10 | Reindeer | Finland | AF525457 | AF525297 |

| E. shiquicus | Pika | China | AB208064 | AB208064 |

| E. felidis | Lion | Uganda | EF558356 | EF558357 |

| E. oligarthrus | Rodent | Panama | M84671 | AJ237642 |

| E. vogeli | Rodent | South America | M84670 | AJ237641 |

| E. multilocularis | Human | Alaska, China | M84668 | AJ237639 |

| E. multilocularis | Rodent | Germany | M84669 | AJ237640 |

| Taenia saginata | Human | Belgium | NC_009938 | NC_009938 |

*Sequences generated in this study.

Results

Distribution of Echinococcus genotypes

Examination of the collected cysts indicated that 3 of 28 cysts derived from dromedary camels were infertile; all others were fertile cysts with protoscoleces. Successful PCR amplification and DNA sequencing were achieved for DNA from all fertile and infertile cysts at all three genetic loci. Genotype identifications at all three genetic loci were in complete agreement for all isolates. Blast search of the obtained sequences derived from camel isolates indicated the occurrence of G6 genotype (E. canadenesis) in 26 of 28 isolates, and G1 (E. granulosus s.s.) and G5 (E. ortleppi) genotypes in one isolate each (35406 and 35408, respectively). Among sheep isolates, G6 and G1 genotypes were seen in 3 and 4 of the 7 isolates, respectively. The 2 isolates derived from buffalo both belonged to the G6 genotype.

Sequence polymorphism in actin II

The alignment of actin II sequences indicated no intra-genotype sequence variation within G6 or G1 genotypes. Sequences of the G6 genotype showed complete identity (100%) to sequences AF528500 generated from hydatid cysts from camels in Algeria [28], and DQ341548 and DQ341551 from cattle and humans from Mauritania [29]. Sequences generated from G1 isolates showed complete identity to relevant sequences in GenBank database from various geographic areas and hosts (FJ997234, FJ997233, EF179175, EF125692, AF528499 and AF528498). The G5 sequence generated from isolate 35408 had one nucleotide substitution (T to C) at position 208 of the reference sequence AF003748 from cattle, and 4 and 7 substitution comparing to sequences AF003749 and AF528500 derived from pigs and camels [26,28], respectively.

Sequence polymorphism in COX1

The alignment of COX1 sequences showed all except one from the G6 genotype in this study were identical. These sequence showed 100% identity to published sequences of G6 derived from different hosts such as AB208063 from camels in Kazakhstan [9], AB458677 from goats in Peru [30], and AB688142 from humans in Russia (direct submission). Only one sequence (35420) had a single nucleotide substitution of C to T at position of 327 of the generated sequences, but was identical to sequence AB650535 generated from camels in Ethiopia [31]. The sequence of G5 genotype showed 99% identity with a single nucleotide substitution of C to T comparing to reference sequences (FJ744757, AB235846 and JX854035) at position 52. No intra-sequence variations were noticed in sequences of the G1 genotype; they were identical to other sequences (KC660075, AB786664, JQ317997, FN646371 and HM598452) in GenBank.

Sequence polymorphism in NAD1

The alignment of NAD1 sequences of G6 genotype isolates showed the presence of 4 types of sequences. The first one contained the majority of sequences and had a complete identity to sequences HM749616, HM749616, HM749617 and HM749618 from camels in Iran [32] and JN637176 from a camel in Sudan [33]. The second type had 4 sequences (37535, 37544, 37545 and 37546) and 2 nucleotide substitutions (both T to A) at positions 315 and 321 comparing to the first type. The third type had only one sequence (37543) and 3 nucleotide substitutions (all T to A) at positions 313, 315 and 321. The fourth type had one sequence (37541) and a single nucleotide substitution (G to C) at position 386. Likewise, two types of G1 sequences were obtained in the study. The first type had 4 sequences and 100% identity to reference sequences AB786664, JQ356721, JF946624, JF946623, GQ358010 HM055622 and others from different countries and hosts. The other sequence was from isolate 37551 and had 2 nucleotide substitutions at positions 281 (T to C) and 321 (T to A). In contrast, isolate 35408 of the G5 genotype generated a sequence identical to G5 sequences JN637177 from camel cysts in Sudan and AB235846 from cattle cysts in Argentina [9], while showed 99% identity to sequence AJ237636 from cattle cysts in the Netherlands [34].

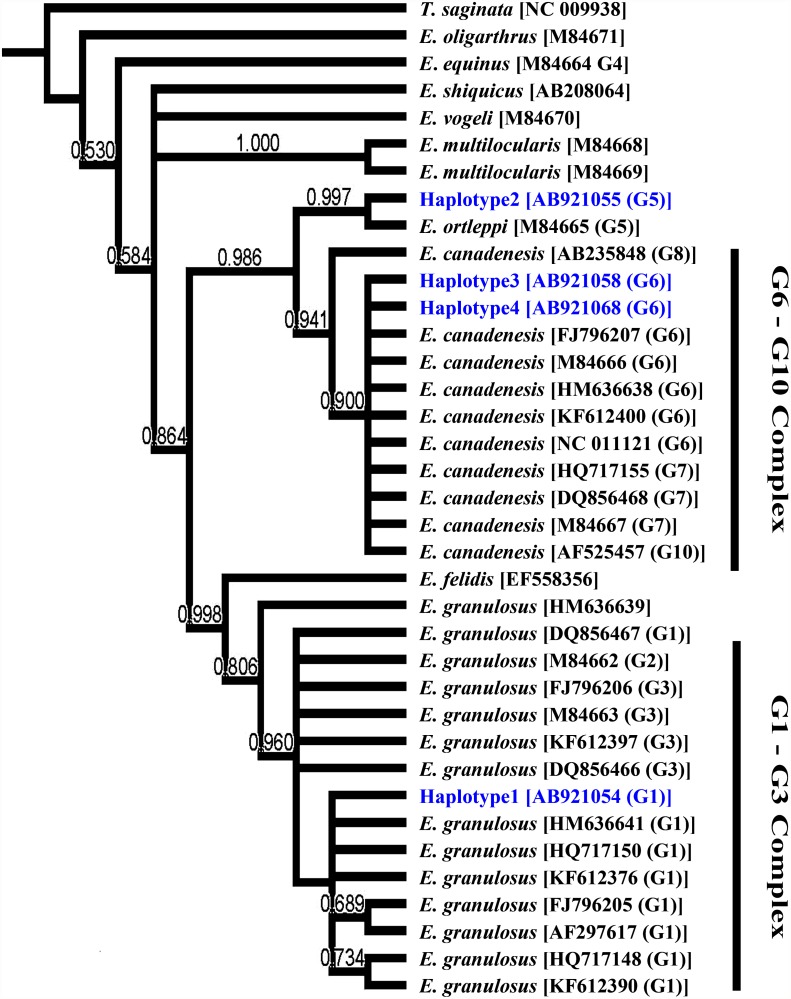

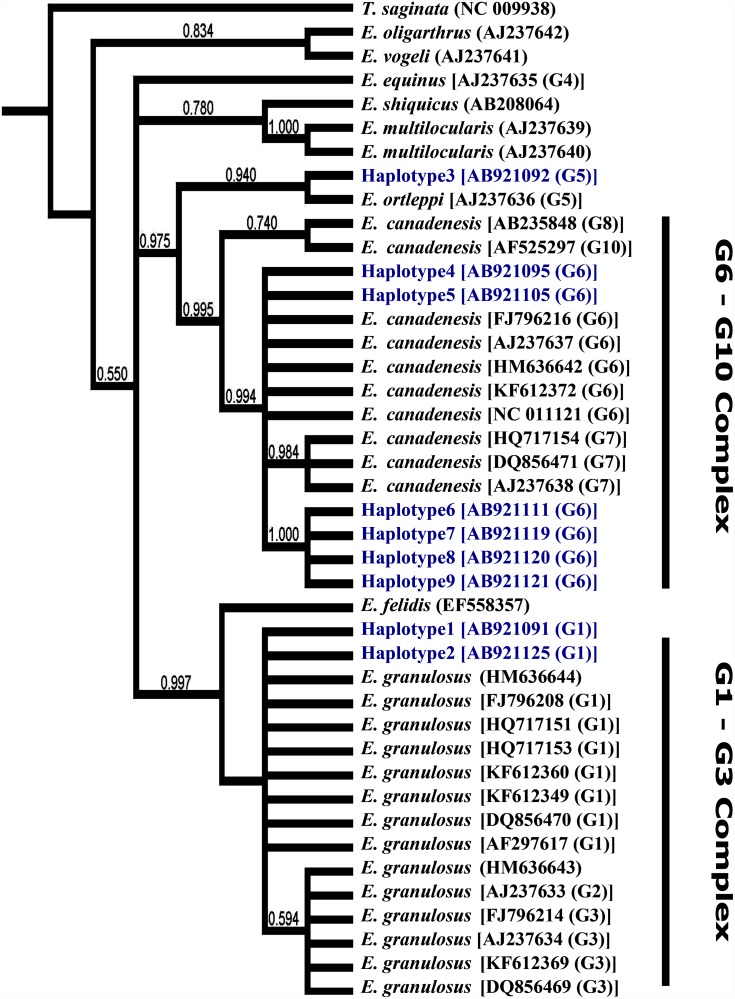

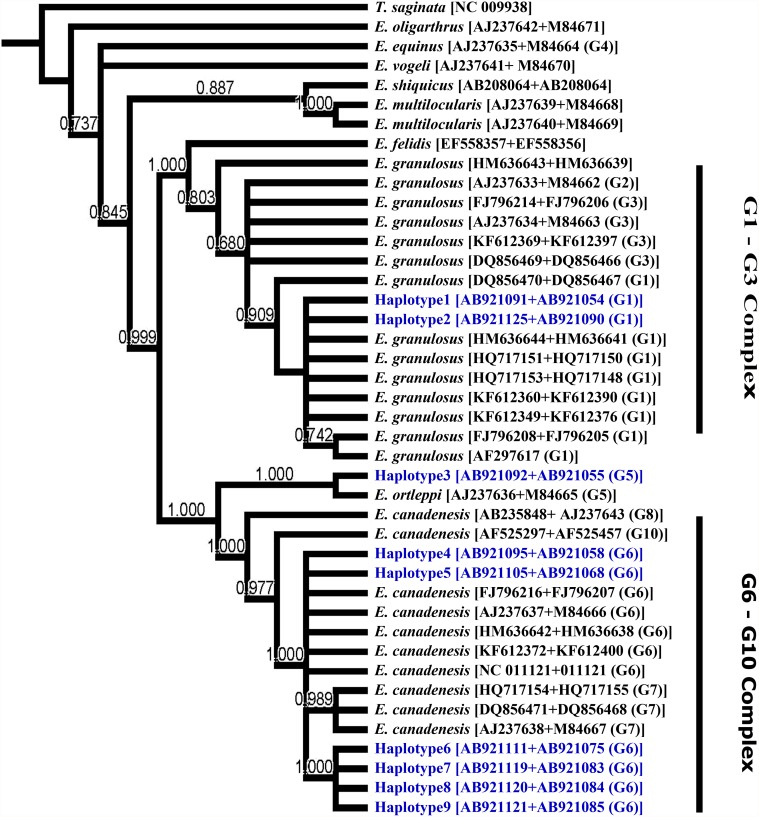

Phylogeny of Echinococcus genotypes

Altogether, 4 haplotypes were detected in COX1 sequences with 2 haplotypes within the G6 genotype, whereas 9 haplotypes were identified at the NAD1 locus with 2 haplotypes within the G1 genotype and 6 haplotypes within the G6 genotype. Phylogenetic trees constructed based on the COX1 (Fig. 1) and NAD1 (Fig. 2) sequences were similar to a tree (Fig. 3) constructed based on the concatenated sequences of both genes. In particular, haplotype 1 of COX sequences grouped with reference sequences from the G1–3 complex, particularly the G1 genotype, with strong bootstrap support (0.90). Haplotype 2 clustered with the E. ortleppi (G5) group, separating from the G6–10 complex with high bootstrap support (0.98). Haplotypes 3 and 4 grouped with the G6 genotype in the G6–G10 complex (bootstrap value = 0.9). Similar distributions of haplotypes within G1–3 and G6–10 complexes were seen in trees constructed based on NAD1 and concatenated sequences. At the genotype level, G5 genotype (E. ortleppi) formed a monophyletic group with G6–10 complex. Similarly, E. felidis was more related to E. granulosus s.s. (G1–G3) forming a sister phylogenetic group (99.0–1.00). Other species were more distant. Thus, E. oligarthrus was very genetically different from other recognized Echinococcus species and genotypes (Figs. 1–3). Likewise, E. vogeli, E. equines (G4), E. multilocularis and E. shiquicus (0.737) were distinct from most E. granulosus s.l. genotypes (G1–G3, G5, and G6–10). Interestingly, E. vogeli grouped with E. oligarthrus in the tree inferred using NAD1 sequences (Fig. 2).

Fig 1. Phylogenetic relationships of Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato isolates from Egypt compared to reference sequences of different Echinococcus species in database.

Evolutionary relationship was inferred based on COX1 sequences (Table 1) using the Bayesian inference (BI) implemented in MrBayes software (version 3.2.2). Taenia saginata (NC_009938) was used as the outgroup.

Fig 2. Phylogenetic relationships of Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato isolates from Egypt compared to reference sequences of different Echinococcus species in database.

Evolutionary relationship was inferred based on NAD1 sequences (Table 1) using the Bayesian inference implemented in MrBayes software (version 3.2.2). Taenia saginata (NC_009938) was used as the outgroup.

Fig 3. Phylogenetic relationships of Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato isolates from Egypt compared to reference sequences of different Echinococcus species in database.

Evolutionary relationship was inferred based on concatenated COX1 and NAD1 sequences (Table 1) using the Bayesian inference implemented in MrBayes software (version 3.2.2). Taenia saginata (NC_009938) was used as the outgroup.

Discussion

CE is endemic in both animals and humans in Egypt [24]. Domestic intermediate hosts are major reservoirs for the disease in humans. Accumulated reports indicated that various livestock are susceptible to hydatid infection in Egypt, with particularly high incidence in camels and sheep [20,35]. In addition, Echinococcus infection is common in stray dogs in Egypt [36], who are usually roaming on streets and near slaughterhouses, feeding on offal of slaughtered animals or carcasses of dead animals in rural areas. Stray dogs also have free access to yards and fields of domestic animals, contaminating the environment with Echinococcus eggs. It is reported that CE is typically a disease of pastoral communities, but less common in agricultural communities [2,18]. Even though Egypt has few pastoral communities, the abundance of stray dogs and common home/street slaughter practices, especially during the festival events, facilitate the establishment of dog-livestock transmission cycle of Echinococcus spp. and increase the risk of human infection [37].

Results reported here indicated that three Echinococcus species are present in farm animals in Egypt, including E. granulosus (sheep genotype or G1), E. canadensis (camel genotype or G6), and E. ortleppi (cattle genotype or G5). The dominance (83.8%) of G6 over the other genotypes (13.5% for G1 and 2.7% for G5) in this study is in agreement with recent reports from Egypt [24,25], which showed exclusive occurrence of G6 in camels and pigs and E. equinus (G4 genotype) in donkeys, and a predominance of G6 with a small number of G1 infections in humans. In contrast, Abd El Baki et al. [38] claimed that G1 was common in humans, camels and sheep using strain specific PCR. Results of the present study have shown a higher diversity of E. granulosus s.l. in Egypt than previously reported, with E. ortleppi being reported for the first time.

The distribution of Echinococcus genotypes differs from country to country and from hosts to hosts. Circulation of the G6 genotype in humans, dromedary camels and cattle was reported in Mauritania [29,39]. This also appears to be the case in Sudan, where G6 is the dominant genotype in humans, camels, cattle, sheep and goats, with some G5 infections in cattle and camels [18,19,33]. Elsewhere, substantial percentages of G6 genotype have been reported in human cases in Argentina (~37%) [40] and Kenya (17%) [17]. Interestingly in Libya, G1 is the exclusive genotype in humans with some occurrence in cattle, whereas G6 dominates in cattle and camels [16]. G1 is also the common genotype in different hosts in Ethiopia [31], Tunisia [39], Palestine [41], Iran [42], India [43], China [44] and Mongolia [45]. Echinococcus granulosus s.s. (G1- G3 complex) is also the major genotype in humans, cattle, sheep and goats in many European and Latin American countries [27,46,47].

The three Echinococcus genotypes detected in this study, G1, G5 and G6, are all known human pathogens [48,49], imposing a significant public health concern. Strains variation may play an important role in not only transmission patterns but also pathogenicity, fertility, and growth rate of hydatid cysts [48]. Considering the fact that most camels for human consumption in Egypt are imported from Sudan, imported camels could be a source of E. canadensis in Egypt. This issue cannot be addressed in the present study because of the low number of cysts analyzed and low resolution of typing tools used. A larger study using a number of isolates from diverse hosts, including humans and stray dogs, from multiple geographic areas is needed to better understand the epidemiology of CE in Egypt.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Kafr El Sheikh University and Al Basatein Abattoir for supporting the field work in Egypt, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for supporting the molecular analysis. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data Availability

Unique nucleotide sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AB921019 to AB921053 for actin II sequences, AB921054 to AB921090 for COX1 sequences, and AB921091 to AB921125 for NAD1 sequences.

Funding Statement

This study was supported in part by the Arab Fund for Economic & Social Development “Zamalat Program” and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 31110103901). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Dowling P, Abo-Shehada M, Torgerson P. Risk factors associated with human cystic echinococcosis in Jordan: results of a case-control study. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000;94: 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eckert J, Gemmell MA, Meslin F, Pawłowski ZS. WHO/OIE manual on echinococcosis in Humans and Animals: A Public Health Problem of Global Concern World Organisation for Animal Health (Office International des Epizooties) and World Health Organisation. 2001; 1–250. [Google Scholar]

- 3. da Silva A. Human echinococcosis: a neglected disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2010;pii: 583297 10.1155/2010/583297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton D. (Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE). Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114: 1–16. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang W, Zhang Z, Wu W, Shi B, Li J, Zhou X, et al. Epidemiology and control of echinococcosis in central Asia, with particular reference to the People's Republic of China. Acta Trop. 2014;141: 235–243. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharafi SM, Rostami-Nejad M, Moazeni M, Yousefi M, Saneie B, Hosseini-Safa A, et al. Echinococcus granulosus genotypes in Iran. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2014;7: 82–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Budke C, Deplazes P, Torgerson P. Global socioeconomic impact of cystic echinococcosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12: 296–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McManus D, Thompson R. Molecular epidemiology and taxononomy of cystic echinococcosis. Parasitol. 2003;127: S37–S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakao M, McManus D, Schantz P, Craig P, Ito A. A molecular phylogeny of the genus Echinococcus inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Parasitol. 2007;134: 713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakao M, Lavikainen A, Yanagida T, Ito A. Phylogenetic systematics of the genus Echinococcus (Cestoda: Taeniidae). Int J Parasitol. 2013;43: 1017–1029. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ito A., Nakao M, Sako Y. Echinococcosis: serological detection of patients and molecular identification of parasites. Future Microbiol. 2007;2: 439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carmena D, Cardona GA. Echinococcosis in wild carnivorous species: Epidemiology, genotypic diversity, and implications for veterinary public health. Vet Parasitol. 2014;202: 69–94. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thompson R, McManus D. Towards a taxonomic revision of Echinococcus . Trends Parasitol. 2002;18: 452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McManus D. Echinococcosis with particular reference to Southeast Asia. Adv Parasitol. 2010;72: 267–303. 10.1016/S0065-308X(10)72010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sadjjadi S. Present situation of echinococcosis in the Middle East and Arabic North Africa. Parasitol Int. 2006;55: S197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abushhewa M, Abushhiwa M, Nolan M, Jex A, Campbell B, Jabbar A, et al. Genetic classification of Echinococcus granulosus cysts from humans, cattle and camels in Libya using mutation scanning-based analysis of mitochondrial loci. Mol Cell Probes. 2010;24: 346–351. 10.1016/j.mcp.2010.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Casulli A, Zeyhle E, Brunetti E, Pozio E, Meroni V, Genco F, et al. Molecular evidence of the camel strain (G6 genotype) of Echinococcus granulosus in humans from Turkana, Kenya. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104: 29–32. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Omer R, Dinkel A, Romig T, Mackenstedt U, Elnahas A, Aradaib IE, et al. A molecular survey of cystic echinococcosis in Sudan. Vet Parasitol. 2010;169: 340–346. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ibrahim K, Thomas R, Peter K, Omer R. A molecular survey on cystic echinococcosis in Sinnar area, Blue Nile state (Sudan). Chin Med J [Engl]. 2011;124: 2829–2833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haridy F, Ibrahim B, Elshazly A, Awad S, Sultan D, El-Sherbini GT, et al. Hydatidosis granulosus in Egyptian slaughtered animals in the years 2000–2005. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2006;36: 1087–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. El Shazly A, Awad S, Nagaty I, Morsy T. Echinococcosis in dogs in urban and rural areas in Dakahlia Governorate, Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2007;37: 483–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Azab M, Bishara S, Helmy H, Oteifa N, El-Hoseiny L, Ramzy RM, et al. Molecular characterization of Egyptian human and animal Echinococcus granulosus isolates by RAPD PCR technique. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2004;34: 83–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Taha H. Genetic variations among Echinococcus granulosus isolates in Egypt using RAPD-PCR. Parasitol Res. 2012;111: 1993–2000. 10.1007/s00436-012-3046-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abdel Aaty H, Abdel-Hameed D, Alam-Eldin Y, El-Shennawy S, Aminou H, Makled SS, et al. Molecular genotyping of Echinococcus granulosus in animal and human isolates from Egypt. Acta Trop. 2012;121: 125–128. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aboelhadid S, El-Dakhly K, Yanai T, Fukushi H, Hassanin K. Molecular characterization of Echinococcus granulosus in Egyptian donkeys. Vet Parasitol. 2013;193: 292–296. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. da Silva CM, Henrique, Ferreira B, Picon M, Gorfinkiel N, Ehrlich R, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of actin genes from Echinococcus granulosus . Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;60: 209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bart J, Morariu S, Knapp J, Ilie M, Pitulescu M, Anghel A, et al. Genetic typing of Echinococcus granulosus in Romania. Parasitol Res. 2006;98: 130–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bart J, Bardonnet K, Elfegoun M, Dumon H, Dia L, Vuitton DA, et al. Echinococcus granulosus strain typing in North Africa: comparison of eight nuclear and mitochondrial DNA fragments. Parasitol. 2004;128: 229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maillard S, Benchikh-Elfegoun M, Knapp J, Bart J, Koskei P, Gottstein B, et al. Taxonomic position and geographical distribution of the common sheep G1 and camel G6 strains of Echinococcus granulosus in three African countries. Parasitol Res. 2007;100: 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moro P, Nakao M, Ito A, Schantz P, Cavero C, Cabrera L. Molecular identification of Echinococcus isolates from Peru. Parasitol Int. 2009;58: 184–186. 10.1016/j.parint.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hailemariam Z, Nakao M, Menkir S, Lavikainen A, Yanagida T, Okamoto M, et al. Molecular identification of unilocular hydatid cysts from domestic ungulates in Ethiopia: Implications for human infections. Parasitol Int. 2012;61: 375–377. 10.1016/j.parint.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rostami Nejad M, Taghipour N, Nochi Z, Mojarad E, Mohebbi S, Harandi MF, et al. Molecular identification of animal isolates of Echinococcus granulosus from Iran using four mitochondrial genes. J Helminthol. 2012;86: 485–492. 10.1017/S0022149X1100071X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ahmed ME, Eltom KH, Musa NO, Ali IA, Elamin FM, Grobusch MP, et al. First report on circulation of Echinococcus ortleppi in the one humped camel (Camelus dromedaries), Sudan. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9: 127 10.1186/1746-6148-9-127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bowles J, McManus D. NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene sequences compared for species and strains of the genus Echinococcus . Int J Parasitol. 1993;23: 969–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dyab K, Hassanein R, Hussein A, Metwally S, Gaad H. Hydatidosis among man and animals in Assiut and Aswan Governorates. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2005;3: 157–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mazyad S, Mahmoud L, Hegazy M. Echinococcosis granulosus in stray dogs and Echino-IHAT in the hunters in Cairo, Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2007;37: 523–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Atkinson J, Gray D, Clements A, Barnes T, McManus D, Yang YR. Environmental changes impacting Echinococcus transmission: research to support predictive surveillance and control. Glob Chang Biol. 2013;19: 677–688. 10.1111/gcb.12088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abd El Baki M, El Missiry A, Abd El Aaty H, Mohamad A, Aminou H. Detection of G1 genotype of human cystic echinococcosis in Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2009;39: 711–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Farjallah S, Busi M, Mahjoub M, Slimane B, Said K, D'Amelio S. Molecular characterization of Echinococcus granulosus in Tunisia and Mauritania by mitochondrial rrnS gene sequencing. Parassitologia. 2007;49: 239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guarnera EA, Parra A, Kamenetzky L, Garcia G, Gutierrez A. Cystic echinococcosis in Argentina: evolution of metacestode and clinical expression in various Echinococcus granulosus strains. Acta Trop. 2004;92: 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Adwan G, Adwan K, Bdir S, Abuseir S. Molecular characterization of Echinococcus granulosus isolated from sheep in Palestine. Exp Parasitol. 2013;134: 195–199. 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shahnazi M, Hejazi H, Salehi M, Andalib A. Molecular characterization of human and animal Echinococcus granulosus isolates in Isfahan, Iran. Acta Trop. 2011;117: 47–50. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sharma M, Fomda BA, Mazta S, Sehgal R, Singh BB, Malla N. Genetic diversity and population genetic structure analysis of Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto complex based on mitochondrial DNA signature. PLoS One. 2013;8: e82904 10.1371/journal.pone.0082904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yan N, Nie H, Jiang Z, Yang A, Deng S, Guo L, et al. Genetic variability of Echinococcus granulosus from the Tibetan plateau inferred by mitochondrial DNA sequences. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196: 179–183. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jabbar A, Narankhajid M, Nolan M, Jex A, Campbell B, Gasser RB. A first insight into the genotypes of Echinococcus granulosus from humans in Mongolia. Mol Cell Probes. 2011;2: 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Beato S, Parreira R, Calado M, Gracio M. Apparent dominance of the G1–G3 genetic cluster of Echinococcus granulosus strains in the central inland region of Portugal. Parasitol Int. 2010;59: 638–642. 10.1016/j.parint.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Piccoli L, Bazzocchi C, Brunetti E, Mihailescu P, Bandi C, Mastalier B, et al. Molecular characterization of Echinococcus granulosus in south-eastern Romania: evidence of G1–G3 and G6–G10 complexes in humans. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19: 578–582. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03993.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thompson RC, Lymbery AJ. Echinococcus: biology and strain variation. Int J Parasitol. 1990;20: 457–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alvarez Rojas CA, Romig T, Lightowlers MW. Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato genotypes infecting humans—review of current knowledge. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44: 9–18. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Unique nucleotide sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AB921019 to AB921053 for actin II sequences, AB921054 to AB921090 for COX1 sequences, and AB921091 to AB921125 for NAD1 sequences.