Abstract

Objective:

Congenital and acquired prothrombotic disorders have been highlighted in a recent series of cerebrovascular stroke (CVS), with a controversial role in pathogenesis. The aim is to study some prothrombotic risk factors [activated protein C (APC) resistance, von Willebrand factor (vWF), anticardiolpin (ACL) antibodies and plasma homocysteine] in children with ischemic stroke, and to evaluate the role of aspirin and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in its management in relation to outcome.

Methods:

A total of 37 cases aged from 1 month to 15 years ( mean ± standard deviation 26.2 ± 35.7 months), diagnosed as ischemic stroke (>24 hours) were recruited. Complete blood count, prothrombin time and concentration, partial thromboplastin time, serum electrolytes, random blood sugar, C-reactive protein, electrocardiogram and echocardiography were done. Levels of APC resistance, vWF, ACL antibodies [immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM)] and plasma homocysteine were estimated. A total of 25 cases received aspirin 3–5 mg /kg/d and 12 patients received LMWH as initial dose at 75 international units (IU)/kg subcutaneously (SC) then 10–25 IU/kg/day for 15 days in a nonrandomized fashion.

Results:

The levels of APC resistance, vWF, ACL antibodies (IgG and IgM) and plasma homocysteine were significantly higher in stroke cases than in controls. There was no significant difference between cases treated with aspirin and those with LMWH in all prothrombotic factors. Significant positive correlations were found between vWF and ACL antibodies (IgG and IgM) levels before treatment. Significant decrease in cognitive function was detected between cases treated with LMWH and those treated with aspirin.

Conclusion:

Ischemic CVS in children is multifactorial. Thrombophilia testing should be performed in any child with CVS. Early use of aspirin improves the prognosis and has less effect on cognitive function.

Keywords: children, prothrombotic risk factors, stroke, therapy

Introduction

The incidence of stroke varies in different countries with respect to the ethnic population background and the number of patients studied [Zivelin et al. 1998]. The incidence of cerebrovascular stroke (CVS) is rare in children (0.6 per 10,000, ranging from 0.2 to 7.9 per 100,000), but it is being increasingly recognized and diagnosed [DeVeber et al. 2001]. Ischemic stroke is associated with increased mortality, life quality impairment and severe disability. The differential diagnosis of ischemic stroke is difficult due to a variety of mimicking stroke conditions and the delay in diagnosis [De Meyer et al. 2012].

The importance of genetic and acquired prothrombotic disorders has been emphasized in a recent series of CVS. The role of these factors in the pathogenesis of stroke is controversial. Common inherited risk factors that have been investigated for thrombosis are antithrombin III, protein C & S deficiency, mutation factor V (Leiden) and factor II variant (G20210A), and sickle cell anemia [Nowak-Göttl et al. 2004].

Factor V Leiden mutation predisposes to thrombosis by producing resistance to activation of protein C, which can be diagnosed by coagulation tests as activated protein C (APC) resistance [Hiatt and Lentz, 2002]. Factor V Leiden is associated with relative risk of ischemic stroke in patients aged less than 50 years. Recently, an association between prothrombotic risk factors and increased levels of von Willebrand Factor (vWF), a marker of endothelial damage dysfunction, among patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) with stroke has been detected [Roldán et al. 2005; van Schie et al. 2010]. However, the true mechanism of stroke with increased level of vWF as a triggering risk factor is still unknown. In addition hyperhomocysteinemia, homocysteinuria and increased lipoprotein levels have been recently shown to introduce significant rare risk factors for thrombosis [Nowak-Göttl et al. 2004]. The acquired risk factors for pediatric thromboembolic stroke include perinatal diseases, medical intervention, acute diseases (sepsis and dehydration), chronic diseases (malignancy, renal, cardiac, collagen and rheumatic diseases) and drugs (prednisone, Escherichia coli asparagenase, heparin, antifibrinolytic agents and contraceptives) [Nowak-Göttl et al. 2004].

Management of stroke in children is different from adults due to age-related differences in the coagulation system, stroke pathophysiology and neuropharmacology. Obstacles to acute stroke include delay in diagnosis and minimizing risk to a vulnerable population [Biller, 2009].

The aim of this work was to evaluate in children with ischemic stroke the following prothrombotic risk factors: APC resistance; vWF; anticardiolpin (ACL) antibodies (Ab) [immunoglobulin (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM)] and plasma homocysteine. The role of antiplatelet agents (aspirin) and anticoagulant therapy [low molecular weight heparin (LMWH)] in the management of CVS in relation to the outcome was also evaluated.

Patients and methods

This study was conducted in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) at the Assiut Children’s University Hospital between December 2010 and February 2012. The study included 37 infants and children (20 ♂ and 17 ♀) taken in a nonrandomized form, aged from 1 month to 15 years (mean 26.2 ± 35.7 months), diagnosed as ischemic stroke (>24 hours) by computerized tomography (C-T) with contrast and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain according to a previously described protocol [Sébire et al. 2005].

Exclusion criteria were children with trauma, brain tumors, condition mimic stroke such as transient postectal hemiparesis, migraine, syndrome of alternative hemiplegia and neonates. The study also included 20 apparently healthy children of matchable age and sex taken as controls. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University, and a written consent was obtained from the children’s parents or legal guardian for participation in the study.

All cases and controls were subjected to full history and clinical examination including family history of stroke, hypertension and diabetes. Routine investigations including complete blood count (CBC), prothrombin time (PT) and concentration, C-reactive protein (CRP), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), serum electrolyte, random blood sugar, electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiography. In addition, levels of APC resistance, vWF, ACL Ab (IgG and IgM) and plasma homocysteine were estimated for all cases and controls.

All cases were under medical treatment for stroke in the PICU according to the cause of stroke and condition of the patients. A total of 25 cases received aspirin 3–5 mg /kg/day and 12 patients received LMWH as initial dose at 75 international units (IU)/kg subcutaneously (SC) then 10–25 IU/kg/day for an average of 15 days in a consecutive non-randomization sampling. Heparin was given in cases with cardiac cause of stroke and four cases with central nervous system (CNS) infections. The side effects of anticoagulants were recorded. Follow up for all cases was done by MRI and /or magnetic resonance venography (MRV) when needed for a period of 1 year at the pediatric neurology outpatient clinic at the Children’s University Hospital to detect recurrence and any neurological sequelae.

The neurological sequelae were assessed by follow up of the patients by EEG, brain MRI and cognition assessment using the Arabic version14 of the Stanford–Binet test (4th edition) [Delany and Hopkins, 1986], a standardized and well-validated psychometric test used to assess memory, attention, language and concentration.

APC resistance assay

APC resistance was determined using the Coatest APC Resistance kit according to the original instructions provided by the manufacturer (Chromogenix, Mölndal, Sweden). In contrast to the APC procedure, the patients’ standard and control plasmas were diluted 1:20 with barbitol buffer to a pH of 7.6 (Behringwerke, Marburg/Lahn, Germany). From each patient’s blood sample, 50 μl of plasma (1:20 diluted) was mixed with 50 μl of factor V deficient plasma and 50 μl of activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) reagent, and incubated for 7 min at 37°C. Thereafter, 50 μl of undiluted APC CaCl2 solution was added. The times of analysis were measured using a Coa Screener coagulometer. The degree of dilution of the APC solution was described as a percentage [Horstkamp et al. 1999].

vWF

Laboratory assays for vWF, a standard ‘antigen’ [antisera enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) based (VWF:Ag)] were evaluated for their ability to detect alterations in VWF levels following differential processing of blood for testing [Favloro et al. 1995].

ACL Ab assay

ACL IgG and IgM were measured using ELISHA kit supplied by ORGENTEC Diagnostica GmbH Cat No. ORG 515 AntiCardiolipin IgG/IgM. Highly purified cardiolipin was bound to micro wells saturated with β2-glycoprotein I. Antibodies against these antigens, if present in diluted serum or plasma, bind to the respective antigen. Washing of the micro wells removed unspecific serum and plasma components. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated antihuman IgG and IgM immunologically detect the bound patient antibodies forming a conjugate/antibody/antigen complex. Washing of the micro wells removes unbound conjugate. An enzyme substrate in the presence of bound conjugate hydrolyzes to form a blue color. Addition of an acid stops the reaction forming a yellow endproduct. The intensity of this yellow color was measured photometrically at 450 nm. The amount of color was directly proportional to the concentration of IgG or IgM antibodies present in the original sample.

Homocysteine assay

Competitive immunoassay with IMMULITE and IMMULITE 1000 in the patient plasma or serum sample releases homocysteine from its binding proteins. It is converted to S-adenosyl-homocysteine (SAH) by an offline 30-min incubation at 37°C in the presence of S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine hydrolase and dithiothreitol (DTT). The treated sample and alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-SAH antibody are introduced simultaneously into a test unit containing an SAH-coated polystyrene bead. During a 30 min incubation, the converted SAH from the patient sample competes with the immobilized SAH for binding of the alkaline phosphatase labeled anti-SAH antibody conjugate. Unbound enzyme conjugate is removed by a centrifugal wash. Substrate is added and the procedure continued as described for typical immunoassays in the operator’s manual. The incubation cycle was 1 × 30 min.

Sample pretreatment

Sample pretreatment working solution (300 μl) was added to prepared tubes. Then 15 μl of patient untreated plasma or serum was added to each tube. The tubes were covered, mixed well and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in a water bath or oven. The treated sample was transferred to an IMMULITE sample cup.

Statistical analysis

The data were collected, categorized and processed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17. The quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and comparison was made using paired a Student’s t-test for two independent groups. Levels of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Correlations between quantitative variables were performed using Pearson correlation and multiple regression analysis by the stepwise method.

Results

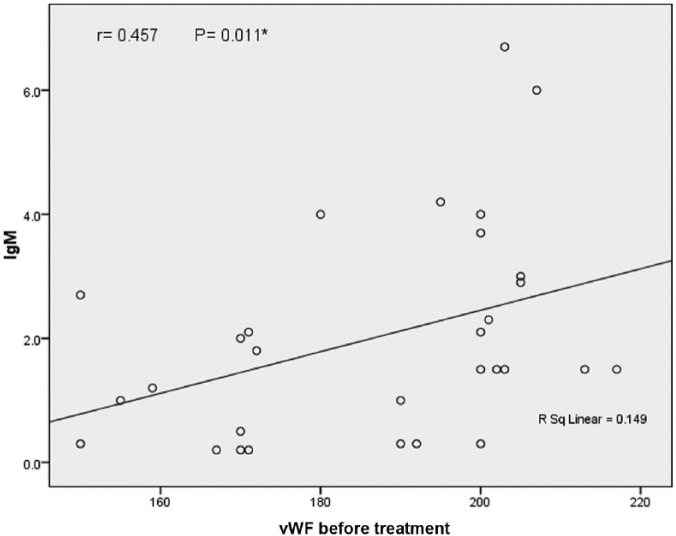

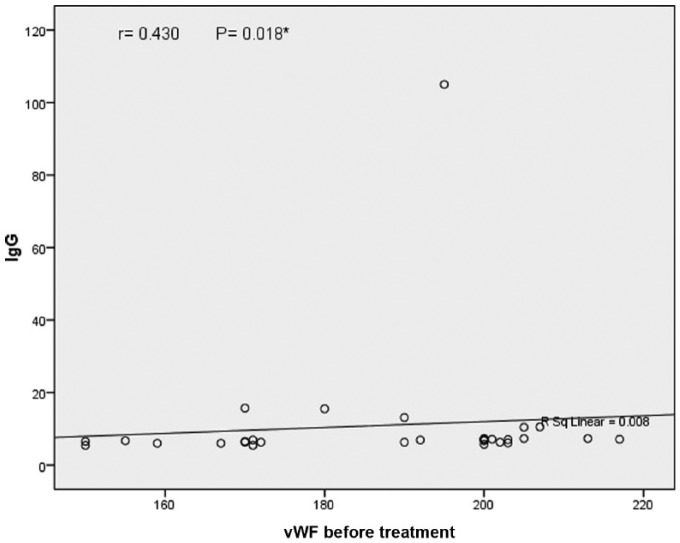

Results are shown in Tables 1 –4 and Figures 1–2.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data for cases with stroke.

| Variables | n= 37 | % | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: (years) | |||

| 1 month to 1 year | 19 | 51.35 | 0.015* |

| 1–2 years | 8 | 21.62 | |

| >2 years | 10 | 27.06 | |

| Mean ± SD; median (range) | 26.2 ± 35.7; 15 (2–168 months) | ||

| Duration of illness: | |||

| <48 hours | 20 | 54.05 | 0.485NS |

| >48 hours | 17 | 45.94 | |

| Mean ± SD (range) | 11.1 ± 8.3 (2–35 days) | ||

| Positive family history of stroke | 8 | 21.62 | <0.001** |

| Positive family history of diabetes mellitus | 3 | 8.10 | <0.001** |

| Irritability | 12 | 32.43 | 0.005** |

| Coma | 18 | 48.64 | 0.877 |

| Vomiting | 18 | 48.64 | 0.877 |

| Convulsions | 30 | 81.08 | <0.001** |

| Hemiparesis | 28 | 75.67 | <0.001** |

| Hypertension | 10 | 27.02 | <0.001** |

| Arrhythmia | 6 | 16.21 | <0.001** |

| Dehydration | 15 | 40.54 | 0.163 |

| Respiratory or gastrointestinal infections | 11 | 28.72 | 0.001** |

mild significance.

high significance.

p value cases versus total number.

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Levels of prothrombotic risk factors in cases* and control.

| Variables (mean ± SD) | Cases (n = 37) | Controls (n = 20) | p value | % of abnormality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT (sec) | 13.25 ± 3.04 | 12. 72 ± 0.42 | 0.360 | 0.8 |

| PTT (sec) | 23.44 ± 1.86 | 34.84 ± 6.80 | 0.000$ | 40.5 |

| APC resistance (%) | 5.12 ± 0.18 | 3.1± 1 | 0.001$ | 30.7 |

| vWF (%) | 204.47 ± 13.37 | 110.81 ± 3.42 | 0.000$ | 32.4 |

| ACL IgG (µ/ml) | 10.91 ± 17.97 | 8.92 ± 0.97 | 0.556 | 30.01 |

| ACL IgM (µ/ml) | 4. 52 ± 1. 70 | 2.15 ± 1.30 | 0.000$ | 27.03 |

| Homocysteine (µmol/l) | 22.7± 9.1 | 8.4± 4.9 | <0.01$ | 50.9 |

A total of 8 cases (21.6%) had more than one prothrombotic risk factor.

p values significant <0.05.

ACL, anticardiolpin; APC, activated protein C; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; SD, standard deviation; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Table 3.

Comparison of prothrombotic risk factors in relation to antithrombotic therapy.*

| Variables (mean ±SD) | Aspirin (n = 25) | LMWH (n = 12) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT (sec) | 13.56 ± 3.48 | 12.38 ± 0.88 | 0.353 |

| PTT (sec) | 35.96 ± 7.07 | 31.75 ± 5.15 | 0.136 |

| APC resistance (%) | 2.17 ± 1.78 | 1.59 ± 1.48 | 0.414 |

| vWF (%) | 202.91 ± 13.37 | 208.75 ± 13.28 | 0.298 |

| ACL IgG (µ/ml) | 7.15 ± 20.93 | 8.50 ± 2.31 | 0.540 |

| ACL IgM (µ/ml) | 3.4± 2.3 | 4. 8±1.8 | 0.41 |

| Homocysteine (µmol/l) | 19.7± 7.35 | 20.7± 9.19 | 0.12 |

No significant differences found between cases treated with aspirin and those treated with LMWH in all the studied parameters.

ACL, anticardiolipin; APC, activated protein C; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; SD, standard deviation; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Table 4.

Frequency of outcome in cases with ischemic stroke in relation to antithrombotic therapy.

| Variables | Aspirin (n = 25) | LMWH (n = 12) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of stay: | |||

| <10 days | 11 (44%) | 5 (41.66%) | 0.893 |

| ⩾10 days | 14 (56%) | 7 (58.33%) | 0.875 |

| Mean ± SD | 10.1 ± 7.4 | 14.0 ± 10.3 | 0.214 |

| Outcome: | |||

| Died | 4 (16%) | 2 (16.66%) | 0.959 |

| Survived | 21 (84%) | 10 (83.33%) | 0.763 |

| Neurological sequelae: | |||

| Epilepsy | 11 (44%) | 7 (58.33%) | 0.414 |

| Hemiparesis | 10 (40%) | 6 (50%) | 0.565 |

| Cognitive deficit | 4 (16%) | 8 (66.6%) | 0.032*. |

p values significant <0.05.

LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Correlation between vWF and ACL Ab IgM.

IgM, immunoglobulin M; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Figure 2.

Correlation between vWF and ACL Ab IgG.

IgG, immunoglobulin G; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

There were 11 cases with vasculitis, 10 cases with CNS infection, 8 cases with cardiac lesions (five cases cyanotic and three cases acyanotic without previous anticoagulant therapy) and eight cases with no predisposing factor (cryptogenic stroke). There were no recurrences during the 1 year follow-up period. No side effects from the use of aspirin or heparin were recorded.

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical data for cases with stroke. Most of the cases (51.3%) were under 1 year of age with a significant difference (p = 0.015). Irritability (p < 0.05), convulsions, hemiparesis, hypertension, arrhythmia and family history of stroke were the main significant presenting symptoms (p < 0.001 for each).

Table 2 presents the levels of prothrombotic risk factors in cases and controls. There was a significant decrease in PTT, and significant increases in APC resistance, vWF, homocysteine and ACL IgM levels between cases and controls (p < 0.001 for each). A total of eight cases (21.6%) had more than one prothrombotic risk factor. Five cases with vasculitis had a combination of APC resistance, ACL IgM and homocysteine, while the remaining three cardiac cases had APC resistance, vWF and homocysteine.

Table 3 shows a comparison of prothrombotic risk factors in relation to antithrombotic therapy. No significant differences between cases treated with aspirin and those treated with LMWH were found in all the studied parameters.

Table 4 represents the outcome in cases with ischemic stroke in relation to antithrombotic therapy. Patients treated with aspirin showed a lower cognitive deficit than those treated with LMWH (16% versus 66 %) with p = 0.03.

Significant positive correlation was detected between vWF and ACL Ab IgM and IgG levels (r = 0.457, p = 0.01 and r = 0.430, p = 0.01, respectively).

Discussion

Ischemic stroke in children is a major cause of significant morbidity and mortality. The most common age of stroke in the present study was under 1 year (51.35%). This agrees with Barnes and colleagues who found a large proportion of childhood stroke occurs in children less than 12 months of age; most survived but with significant neurological deficits [Barnes et al. 2004]. Biller stated that infants are at risk for stroke due to abnormal blood flow resulting from arrhythmia or abnormal anatomy, or change in perfusion during cardiac surgery, or impaired cerebral perfusion and polycythemia [Biller, 2009]. Nowak-Göttl and colleagues stated that the distribution of prothrombotic risk factors varies in different countries based on age-dependent references [Nowak-Göttl et al. 2004]. However, DeVeber and colleagues showed no significant difference in ratio of normal to abnormal coagulation tests when analyzed by different age groups with or without additional risk factors or family history of coagulation disorders [DeVeber et al. 1998].

Positive family history of stroke was found in eight cases (21.62 %) in this series, which is comparable with Karttunen and colleagues who found 14% [Karttunen et al. 2003]. Jastrzebska and colleagues found that parents with history of stroke had a procoagulant state with high levels of vWF, fibrinogen and protein C in terms of inheritance [Jastrzebska et al. 2002]. Seizure was the most common presentation in this study (81.08%); this agrees with previous studies [Makhija et al. 2008; Del Balzo et al. 2009] where convulsion was in 76% but differs from those reported by Sébire and colleagues who found convulsions in 40% [Sébire et al. 2005]. However, they stated that stroke may be subtle and has been associated with poor performance (visual or auditory). Hypertension was present in 27.02% of our cases. This could be due to the higher percent of vasculitis (11 cases) and this agrees with the findings of Turan and colleagues [Turan et al. 2007]. Respiratory and gastrointestinal infections were present in 28.72% of the present study’s cases. This is consistent with the findings of Emsley and colleagues who stated that infections and dehydration appear to be triggering factors that present one-third of stroke causes through a pathogenic mechanism by blocking blood flow to the tissues [Emsley et al. 2008].

Thrombosis occurs as a result of interaction between coagulation and fibrinolysis, leading to a prothrombotic state. PTT was significantly shortened in the studied cases compared with the controls. The percentage of abnormality was 40.5%. This agrees with previous studies [Nowak-Göttl et al. 2004; Biller, 2009] who found a shortened PTT, but since similar values were noted in their control subjects of the same age, little value can be placed on this finding

APC resistance was significantly higher in stroke cases than controls with an abnormal percentage of 30.7%. This agrees with a previous study [Karttunen et al. 2003]. The role of APC resistance in CVS remains to be elucidated. Factor V circulates in plasma as an active cofactor; activation by thrombin results in factor Va, which serves as a cofactor for the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin. Factor V is controlled by APC to stop blood from forming clots (APC can easily turn off Factor V) and Factor Va inactivation is an ordered event. Factor Va is elevated at arginine 500, and then arginine 306 and arginine 679, by APC [Castoldi and Rosing, 2010]. Factor V Leiden results from the replacement of arginine with glutamine at amino acid position 50 (R500 Q) [Ragni, 2011]. Factor V Leiden is a genetically acquired trait that can result in thrombophilia (hypercoagulable state), resulting in the phenomenon of APC resistance, where mutation of the Factor V gene changes Factor V protein, making it resistant to inactivation by protein C [Martinelli et al. 2000]. Thus APC does not work in abnormal Factor V (Leiden protein) and takes longer to turn off Factor V Leiden. This is why people with this mutation clot more than those without it. In addition, all prothrombotic Factor V mutations (Factor V Leiden, Factor V Cambridge, Factor V Hong Kong) make it resistant to cleavage by APC (APC resistance) [Martinelli et al. 2000]. It therefore remains active and increases the rate of thrombin generation [Ragni, 2011].

Factor V Leiden is the most common cause of inherited thrombophilia in Caucasian populations (40–50%) and deep venous thrombosis compared with controls (10%) [Castoldi and Rosing, 2010]. It is uncommon in Asia, Africa and Latin America (10%) [Martinelli et al. 2000]. It was reported recently as risk factor for CVS in children of Mediterranean origin [Duran et al. 2005].

In this study, levels of vWF were significantly higher in the cases than in the controls, with abnormalities in 32.4% of cases. This is consistent with the work of Folsom and colleagues who reported that vWF concentration was 20% higher in stroke cases than in those who remained free of cardiovascular disease, but the difference was not statistically significant [Folsom et al. 1999]. Plasma vWF, which is synthesized primarily by vascular endothelial cells, has three major activities: (1) mediating platelet adhesion to damaged arterial walls; (2) mediating platelet aggregation at high shear stress; and (3) binding and stabilizing Factor VIII. Vascular injury or stress increases vWF synthesis, so an elevated plasma vWF level may reflect excessive endothelial stress. Increased vWF levels may therefore augment platelet adhesion, enhance shear stress induced platelet aggregation, and increase plasma Factor VIIIc levels, thereby increasing the risk of cerebral thrombosis when atherosclerotic plaques rupture.The results in the present study are higher than those reported by Conway and colleagues who stated that raised vWF can predict clinical outcome (including stroke in AF) [Conway et al. 2003]. Thus the observed relationship between vWF and stroke may be related to the wide spread endothelial damage dysfunction and local atherothrombosis rather than to thromboembolism from left atrial appendix. Previous studies [Heppell et al. 1997; Goldsmith et al. 2000] found that raised vWF is predictive of thrombosis in damaged atrial appendage endocardium in patients with mitral valve disease and heart failure, whereas Fukuchi and colleagues found correlation between endocardial expression of vWF and the degree of platelet adhesion and thrombus formation in atrial appendage [Fukuchi et al. 2001].

In relation to ACL Ab, both IgG and IgM levels were higher in the studied cases than controls with abnormalities of 30.01% and 27.03%, respectively. Also there was a positive correlation between vWF and ACL Ab before treatment. This may be explained by the higher percentage of vasculitis in our cases and is also consistent with research by DeVeber and colleagues, who stated that a significant proportion of children with thromboembolism had predominance of ACL Ab (33%) [DeVeber et al. 1998]. Previous studies [Folsom et al. 1999; Conway et al. 2003; Heppell et al. 1997] reported that elevation of vWF is also associated with an increased risk of CVS. In addition, Hiatt and Lentz found that antiphospholipid Ab are found in 1–5% in controls and 40% in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE] [Hiatt and Lentz, 2002]. Mishra and Rohatgi found ACL (lupus anticoagulant and ACL) is present in 29.4% of patient and 4% of controls [Mishra and Rohatgi, 2009]. The clinical importance of ACL Ab increases with its titer and the significance of this titer below 40 phospholipid units IgG and IgM0 is uncertain. This test should be deferred after several weeks of discontinuing anticoagulants [Hiatt and Lentz, 2002]. However, Lanthier and colleagues found that, in children with arterial ischemic stroke, the increase in ACL IgG titer did not predict recurrence of thromboembolism [Lanthier et al. 2004]. The association between ACL and CVS is still controversial. Some studies demonstrated association between antiphospholipid and systemic stroke, but others found no association. However, children with thrombophilia, as well as their mothers, apart from carrying the risk for CVS, may be predisposed to higher risk of thrombosis or pregnancy complications [Simchen et al. 2009].

Plasma homocysteine was significantly higher in this series than controls (22.7 ± 9.1 versus 8.4 ± 4.9) with percentage of abnormality of 50.9%.This agrees with previous studies [Hiatt and Lentz, 2002; Perini et al. 2005], who found moderate hyperhomocysteinemia (15–100 mg/l) in 20–30% of patients with ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease and venous thrombosis. The elevated homocysteine may be caused by genetic defect in methionine metabolism, renal failure or deficiency of foliate or B 12 [Selhub, 1999]. Homocysteine is an important risk factor for vascular disease due to its procoagulative effect and induces endothelial damage [Ganesan et al. 2006]. Khajuria and Houston explain the effect of homocysteine on coagulation factors by increasing thrombin generation, which in turn induce monocytes expression, and tissue factor which is the key protein of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation [Khajuria and Houston, 2000]. Therefore, hypercoagulable state can be detected by screening tests in most patients and should include lupus anticoagulant, ACL and plasma homocysteine, CRP, plasminogen, clotting time and lipoprotein A. However, Ostovan and colleagues stated that hypercoagulative state as a cofactor in cardiovascular accident patients with patent foramen ovale did not seems to be a direct risk factor for embolic cardiovascular accident at least any higher than in the normal population [Ostovan et al. 2010].

Thrombolytic therapy management of stroke in children is different from adults due to age-related differences in the coagulation system, stroke pathophysiology and neuropharmacology. Obstacles to acute stroke include delay in diagnosis and minimizing risk to a vulnerable population. Sträter and colleagues stated that a low dose of aspirin is probably beneficial in stroke [Sträter et al. 2004], while Dix and colleagues stated that LMWH is effective and safe not only in patient with venous thrombosis but also in stroke [Dix et al. 2000]. Although aspirin is the more cost-effective and its administration more convenient than LMWH, LMWH is more appropriate in venous vascular accident associated with prothrombotic risk factors [Coull et al. 2002]. The antiplatelet action of aspirin starts several days after administration and aspirin should never replace heparin therapy when there is a high risk of recurrent ischemic stroke or embolism [Roach et al. 2008].

There was no significant difference between cases who received aspirin and cases who received LMWH in all prothrombotic risk factors in the present study. This agrees with previous studies [Sträter et al. 2001; Berge et al. 2000] who stated that, in prospective multicenter studies, LMWH is not superior to a medium dose of aspirin in preventing recurrence because stroke type, basic disease and the underlying prothrombotic risk factors are essential controlling factors. Monagle and colleagues recommended LMWH or aspirin as initial therapy until the cause of the embolism has been excluded [Monagle et al. 2008]. Also McCabe and colleagues stated that vascular stroke commonly occurs in patients on aspirin and may reflect incomplete inhibition of platelet function with aspirin therapy [McCabe et al. 2005]. The platelet function analysis (PFA-100) activates platelets by aspirating the blood sample at a moderate or higher sheet rate through a capillary to a biologically active membrane with a central aperture. This membrane is coated with collagen and either adenosine diphosphate (ADP) or epinephrine [Coull et al. 2002]. The time taken for activated platelets to adhere, aggregate and occlude the aperture is called the closure time. Aspirin prolongs the epinephrine closure time without prolongation of ADP closure time in control subjects. PFA-100 is a sensitive assay for the detection of early phase cardiovascular disease in patients who had incomplete inhibition of platelet function with aspirin. There was an inverse relationship between vWF antigen and epinephrine closure time. Hence vWF play an important role in mediating aspirin nonresponsiveness on PFA-100 [Coull et al. 2002]. Also Conway and colleagues stated that vWF itself may play an important role in the mechanism behind stroke and cardiovascular outcome among aspirin-treated AF patients and might represent a target for novel therapies or adjunctive aid to risk stratification to AF [Conway et al. 2003]. Therefore, vWF could be a promising target in stroke therapy [De Meyer et al. 2012]. There is no convening evidence that anticoagulants are effectively influenced by stroke subtype [Coull et al. 2002].

As regarding the outcome, there was no significant difference between cases receiving aspirin and cases received LMWH in relation to duration of hospital stay, survival rate and neurological sequel except for cognitive defect. Cases with aspirin therapy in this study showed a significantly lower cognitive defect than those who received LMWH (16% and 66.6%, respectively). This is in accordance with Sébire and colleagues who found a cognitive defect in 34% of cases [Sébire et al. 2005], but disagrees with the Multicentre Acute Stroke Trial–Italy (MAST-I) Group which found no effect of aspirin either alone or with streptokinase on the morbidity rate [MAST-1, 1995]. However, Coull and colleagues stated that an antiplatelet agent (aspirin) in acute stroke presenting <48 hours should be given in a dose of 165–325 mg/kg/day to reduce mortality and morbidity, provided contraindications (allergy and gastrointestinal bleeding) are absent [Coull et al. 2002].

Also regarding fractionated heparin SC, the available data demonstrated no reduction in mortality and morbidity. SC LMWH may be considered for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis in patients at risk of ischemic stroke. The benefit is negated by a concomitant increase in occurrence of hemorrhage. Therefore, the use of SC unfractionated heparin is not recommended for reducing the risk of death or stroke-related morbidity, or for preventing early stroke recurrence. The positive benefit of these agents must be weighed against the risk of systemic and intracranial hemorrhage [Coull et al. 2002]. The relatively small number of cases in this study limits an estimation of the magnitude of risk factors for stroke.

Conclusion

Ischemic CVS in children is multifactorial with more than one risk factor affected, both inherited or acquired. Aspirin improves the prognosis as it is easier to administer and cheaper, lowers morbidity and has less effect on cognitive function. Thrombophilia testing should be performed in any child with CVS and positive tests may eventually lead to therapy to reduce the risk of recurrence. A randomized, prospective study is needed to clarify the benefit of antithrombotic therapy in prevention of recurrence in stroke patients with prothrombotic abnormalities.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge grant support to all staff members and nursing team in the pediatric intensive care unit at Assiut Children’s University Hospital, Egypt, for their help and cooperation in this work.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributor Information

Azza A. Eltayeb, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Children University Hospital, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt

Gamal A. Askar, Children University Hospital, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt Assistant Prof of Pediatrics, Children University Hospital, Assiut University, Egypt

Naglaa H. Abu Faddan, Children University Hospital, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt Assistant Prof of Pediatrics, Children University Hospital, Assiut University, Egypt

Taghreed M. Kamal, Assiut University Hospital, Assiut University, Egypt

References

- Barnes C., Newall F., Furmedge J., Mackay M., Monagle P. (2004) Arterial ischaemic stroke in children. J Paediatr Child Health 40: 384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge E., Abdelnoor M., Nakstad P., Sandset P. (2000) Low molecular-weight heparin versus aspirin in patients with acute ischaemic stroke and atrial fibrillation: a double-blind randomised study. Lancet 355: 1205–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biller J. (2009) Stroke in Children and Young Adults, 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Castoldi E., Rosing J. (2010) APC resistance: biological basis and acquired influences. J Thromb Haemost 8: 445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway D., Pearce L., Chin B., Hart R., Lip G. (2003) Prognostic value of plasma von Willebrand factor and soluble P-selectin as indices of endothelial damage and platelet activation in 994 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Circulation 107: 3141–3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull B., Williams L., Goldstein L., Meschia J., Heitzman D., Chaturvedi S., et al. (2002) Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents in acute ischemic stroke: report of the Joint Stroke Guideline Development Committee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Stroke Association (a division of the American Heart Association). Neurology 59: 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Meyer S., Stoll G., Wagner D., Kleinschnitz C. (2012) Von Willebrand factor: an emerging target in stroke therapy. Stroke 43: 599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Balzo F., Spalice A., Ruggieri M., Greco F., Properzi E., Iannetti P. (2009) Stroke in children: inherited and acquired factors and age-related variations in the presentation of 48 paediatric patients. Acta Paediatr 98: 1130–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delany E., Hopkins T. (1986) The Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scale: Fourth Edition, Examiner’s Handbook. Chicago, IL: Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- DeVeber G., Andrew M., Adams C., Bjornson B., Booth F., Buckley D., et al. (2001) Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis in children. N Engl J Med 345: 417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVeber G., Monagle P., Chan A., MacGregor D., Curtis R., Lee S., et al. (1998) Prothrombotic disorders in infants and children with cerebral thromboembolism. Arch Neurol 55: 1539–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix D., Andrew M., Marzinotto V., Charpentier K., Bridge S., Monagle P., et al. (2000) The use of low molecular weight heparin in pediatric patients: a prospective cohort study. J Pediatr 136: 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran R., Biner B., Dermir M., Celtik C., Karasalihoglu S. (2005) Factor V Leiden mutation and other thrombophilia markers in childhood ischemic stroke. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 11: 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley H., Smith C., Tyrrell P., Hopkins S. (2008) Inflammation in acute ischemic stroke and its relevance to stroke critical care. Neurocrit Care 9: 125–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaloro E., Facey D., Grispo L. (1995) Laboratory assessment of von Willebrand factor. Use of different assays can influence the diagnosis of von Willebrand’s disease, dependent on differing sensitivity to sample preparation and differential recognition of high molecular weight VWF forms. Am J Clin Pathol 104: 264–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom A., Rosamond W., Shahar E., Cooper L., Aleksic N., Nieto F., et al. (1999) Prospective study of markers of hemostatic function with risk of ischemic stroke. Circulation 100: 736–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi M., Watanabe J., Kumagai K., et al. Increased von Willebrand factor in the endocardium as a local predisposing factor for thrombogenesis in overloaded human atrial appendage. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 37: 1436–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan V., Prengler M., Wade A., Kirkham F. J. (2006) Clinical and radiological recurrence after childhood arterial ischemic stroke. Circulation, 114 (20) pp. 2170–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith I., Kumar P., Carter P., Blann A., Patel R., Lip G. (2000) Atrial endocardial changes in mitral valve disease: a scanning electron microscopy study. Am Heart J 140: 777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppell R., Berkin K., McLenachan J., Davies J. (1997) Haemostatic and haemodynamic abnormalities associated with left atrial thrombosis in nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. Heart 77: 407–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt B., Lentz S. (2002) Prothrombotic states that predispose to stroke. Curr Treat Options Neurol 4: 417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstkamp B., Kiess H., Krämer J., Riess H., Henrich W., Dudenhausen J. (1999) Activated protein C resistance shows an association with pregnancy-induced hypertension. Hum. Reprod 14: 3112–3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastrzebska M., Torbus-Lisiecka B., Honczarenko K., Foltynska A., Chełstowski K., Naruszewicz M. (2002) Von Willebrand factor, fibrinogen and other risk factors of thrombosis in patients with a history of cerebrovascular ischemic stroke and their children. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 12: 132–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karttunen V., Hiltunen L., Rasi V., Vahtera E., Hillbom M. (2003) Factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene mutation May predispose to paradoxical embolism in subjects with patent foramen ovale. Blood Coagulation Fibrinolysis 14: 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khajuria A., Houston D. (2000) Induction of monocyte tissue factor expression by homocysteine: a possible mechanism for thrombosis. Blood 96: 966–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanthier S., Kirkham F., Mitchell L., Laxer R., Atenafu E., Male C., et al. (2004) Increased anticardiolipin antibody IgG titers do not predict recurrent stroke or TIA in children. Neurology 62: 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhija S., Aneja S., Tripathi R., Narayan S. (2008) Etiological profile of stroke and its relation with prothrombotic states. Ind J Pediatr 75: 579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli I., Bucciarelli P., Margaglione M., De Stefano V., Castaman G., Mannucci P. (2000) The risk of venous thromboembolism in family members with mutations in the genes of factor V or prothrombin or both. Br J Haematol 111: 1223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe D., Harrison P., Mackie I., Sidhu P., Lawrie A., Purdy G., et al. (2005) Assessment of the antiplatelet effects of low to medium dose aspirin in the early and late phases after ischaemic stroke and TIA. Platelets 16: 269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra M., Rohatgi S. (2009) Antiphospholipid antibodies in young Indian patients with stroke. J Postgrad Med 55: 161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monagle P., Chalmers E., Chan A., DeVeber G., Kirkham F., Massicotte P., et al. (2008) Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest 133(Suppl. 6): 887S-968S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multicentre Acute Stroke Trial–Italy (MAST-I) Group (1995) Randomised controlled trial of streptokinase, aspirin, and combination of both in treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet 346: 1509–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Göttl U., Duering C., Kempf-Bielack B., Sträter R. (2003) Thromboembolic diseases in neonates and children. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb 33: 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostovan M., Nikfarjam D., Moaref A., Aghasadeghi K. (2010) Assessment of hypercoagulation state in patients with embolic cerebrovascular or transient ischemic attack and patent foramen ovale. Int Cardiovascul Res J 4: 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Perini F., Galloni E., Bolgan I., Bader G., Ruffini R., Arzenton E., et al. (2005) Elevated plasma homocysteine in acute stroke was not associated with severity and outcome: stronger association with small artery disease. Neurol Sci 26: 310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragni M. (2011) Hemorrhagic disorders: coagulation factor deficiencies. In: Goldman L., Schafer A. (eds), Cecil Medicine, 24th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier, Chapter; 167. [Google Scholar]

- Roach E., Golomb M., Adams R., Biller J., Daniels S., deVeber G. (2008) Management of stroke in infants and children. A scientific statement from a special writing group of the American Heart Association Stroke Council and the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Stroke 39: 2644–2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roldán V., Marín F., García-Herola A., Lip G. (2005) Correlation of plasma von Willebrand factor levels, an index of endothelial damage dysfunction, with two point-based stroke risk stratification scores in atrial fibrillation. Thromb Res 116: 321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sébire G., Tabarki B., Saunders D., Leroy I., Liesner R., Saint-Martin C., et al. (2005) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in children: risk factors, presentation, diagnosis and outcome. Brain 128: 477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selhub J. (1999) Homocysteine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr 19: 217–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simchen M., Goldstein G., Lubetsky A., Strauss T., Schiff E., Kenet G. (2009) Factor V Leiden and antiphospholipid antibodies in either mothers or infants increase the risk for perinatal arterial ischemic stroke. Stroke 40: 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sträter R., Kirkham F., deVeber G., Chan A., Ganesan V., Nowak-Göttl U. (2004) Recurrent arterial ischemic stroke in childhood: the role of prothrombotic disorders and underlying conditions. Neuropediatrics 35: abstract V22. [Google Scholar]

- Sträter R., Kurnik K., Heller C., Schobess R., Luigs P., Nowak-Göttl U. (2001) Aspirin versus low-dose low-molecular-weight heparin: antithrombotic therapy in pediatric ischemic stroke patients: a prospective follow-up study. Stroke 32: 2554–2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan T., Cotsonis G., Lynn M., Chaturvedi S., Chimowitz M., for the Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) Trial Investigators (2007) Relationship between blood pressure and stroke recurrence in patients with intracranial arterial stenosis. Circulation 115: 2969–2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schie M., De Maat M., Dippel D., de Groot P., Lenting P., Leebeek F., et al. (2010) Von Willebrand factor propeptide and the occurrence of a first ischemic stroke. J Thromb Haemost 8: 1424–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivelin A., Rosenberg N., Faier S., Kornbrot N., Peretz H., Mannhalter C., et al. (1998) A single genetic origin for the common prothrombotic G20210A polymorphism in the prothrombin gene. Blood 92: 1119–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]