Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to assess the rate of antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence and to identify any determinants among adult patients.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 351 ART patients in the ART clinic of the University of Gondar referral hospital. Data were collected by a pretested interviewer-administered structured questionnaire from May to June 2014. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine factors significantly associated with adherence.

Results

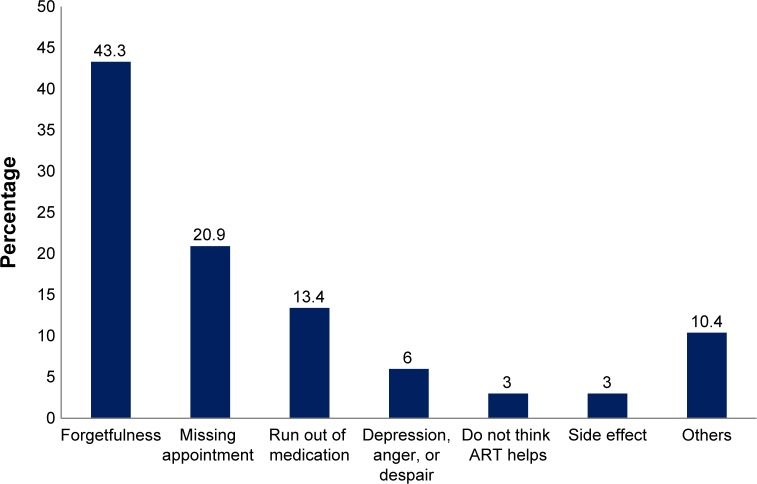

Of 351 study subjects, women were more predominant than men (64.4% versus 35.6%). Three hundred and forty (96.9%) patients agreed and strongly agreed that the use of ART is essential in their life, and approximately 327 (93.2%) disclosed their sero-status to family. Seventy-nine (22.5%) participants were active substance users. The level of adherence was 284 (80.9%). Three hundred forty-one (97.2%) respondents had good or fair adherence. Among the reasons for missing doses were forgetfulness (29 [43.3%]), missing appointments (14 [20.9%]), running out of medicine (9 [13.4%]), depression, anger, or hopelessness (4 [6.0%]), side effects of the medicine used (2 [3.0%]), and nonbelief in the ART (2 [3.0%]). The variables found significantly associated with non-adherence were age (P-value 0.017), employment (P-value 0.02), HIV disclosure (P-value 0.04), and comfortability to take ART in the presence of others (P-value 0.02).

Conclusion

From this study, it was determined that forgetfulness (43.3%) was the most common reason for missing doses. Also, employment and acceptance in using ART in the presence of others are significant issues observed for non-adherence. Hence, the ART counselor needs to place more emphasis on the provision and use of memory aids.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, adherence, determinants, Ethiopia, Africa

Introduction

According to the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) resource center statistics in 2011, there are 249,179 adult human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients in Ethiopia, who have been registered for the antiretroviral therapy (ART) medication.1 Adherence to ART results in successful HIV outcomes, which ensures optimal viral and CD4 control and prevention of further complications.2 However, adherence to ART often poses a special challenge and requires commitment from the patient and the health care team.3,4 Due to rapid replication and mutation of HIV, poor adherence results in the development of drug-resistant strains of HIV.5 For ideal CD4 count and long-term suppression of viral load in patients, adherence to ART must be >95.0%.6 ART adherence can be classified as “good” when the patient misses three or less doses, “fair” between three and eight doses, and “poor” missing more than eight doses per month.3

Several factors have been associated with poor adherence including low levels of health literacy or numeracy, certain age-related/cognitive challenges, psychosocial issues, nondisclosure of HIV sero-status, substance abuse, stigma, and difficulty with taking medication.7 In addition, house- and work-related activities are some other challenges to adherence to ART.6 Furthermore, a meta-analysis conducted by Mills et al examined barriers and facilitators of ART adherence in 72 developed and 12 developing country settings (five African). Main barriers to ART adherence included fear of disclosure, forgetfulness, health illiteracy, substance abuse, complicated regimens, and patients being away from their medications.8 Moreover, in developing countries, financial constraints, sex-related issues, and stigma remained a barrier to the access and adherence to ART.9–13

In the presence of various barriers affecting the taking of ART, like economic, institutional, and cultural, non-adherence to ART is estimated at between 50% and 80% in different social and cultural settings.14 For example, in Brazil, cumulative incidence of non-adherence to ART is noted to be 36.9%, while in South Africa, it was noted to be varying from 10% to 37%.15–18

Addressing the situation in Ethiopia, the adherence to ART level was found to be 74.2%.19 Forgetting to take the medicine, changes in daily routine, and being away from home are identified to be three main reasons for non-adherence.20,21 Another Ethiopian study reported that the adherence rate was 72.4%, and the adherence was higher among patients who have family support than among people living independently.20–24 The reasons for non-adherence were found to be running out of medications (27.3%), being away from home (21.2%), and being busy with other things (21.2%).20 However, up until now, there is a lack of any recent data that address barriers to ART adherence in Gondar city, Ethiopia. Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine the level of adherence and factors associated with it among HIV patients receiving ART at the University of Gondar referral hospital. This study is meant to fill the information gap pertaining to ART adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). Understanding the factors affecting it can increase a clinician’s attention to adherence when working with particularly susceptible patients and can inform the development of interventions.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from May to June 2014 at the University of Gondar referral hospital, a pioneer in this work and the highest referral center in Northwest Ethiopia. The ART clinic in the hospital provides voluntary counselling and testing and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) to 4,158 PLWHA. Gondar is the historical capital city and is located in the Amhara region in the northwest part of Ethiopia. The estimated population of Gondar is approximately 206,987, of whom 98,085 are men and 108,902 are women.25

Study sample

Those PLWHA taking ART for at least 2 months, who were above the age of 18 years and volunteered to give informed consent, were included in the study.

Accordingly, the study involved 351 voluntary patients, who attended the ART pharmacy for refill, during the study period. Convenient sampling technique was used to approach the respondents. Data were collected using face-to-face interviews and a pretested questionnaire. The principal investigator followed the data collection process and made the necessary corrections on the spot. Health research ethical approval was obtained from the University of Gondar Research and Ethics Committee.

Structure of data collection tool

A structured pretested questionnaire with 21 items, which is developed from different literature, was used for data collection purpose.6–13 The first section of the questionnaire constituted ten items relating to sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors, including age, sex, education, occupation, marital status, religion, living conditions, and family income. The second section constituted five questions relating to the knowledge, attitude, and practice of PLWHA toward ART medications, which were rated using the Likert scale and yes/no answers. Five items related to treatment-related variables, comprising the following: duration of therapy classified as <6 months, 6–12 months, 12 months to 3 years, and >3 years; side effects of treatment as yes/no; satisfaction with health care providers, from satisfaction all the time to little satisfaction most of the time; any missing dose over the past 1 month; and the number of missing doses observed using pill count. Therefore, a lack of correct behavior was defined as non-adherence. The correct behavior was meant to describe each patient’s HAART-taking behavior, without missing doses.

The final section includes one question related to the reasons for non-adherence to ART medication, to the relevant patients. All the interviews were done face-to-face by the researcher, to ensure that all questions were clear and there was no chance of confusion or misunderstanding.24

Data analysis

The data were analyzed by the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows software application program version 20.0, and frequencies, percentages, cross tabulation, and odds ratio (OR) of different variables were determined. Binary logistic regression was used to determine factors significantly associated with non-adherence. Associations were considered significant at P<0.05. All variables statistically significant at the P<0.25 level in bivariate analyses were included in the multivariate model so that confounding factors were excluded.

Results

Sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics of respondents

A total of 351 voluntary patients, who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, were enrolled as subjects for this study. There were more females than males, and the majority were in the range of 31–45 years of age (38.2%). Nearly half of the respondents were married (49.9%) and 87.5% were Christian orthodox. Most of the respondents (31.1%) had elementary-level education with a monthly income of 500–1,500 Birr (72.6%). They lived with their family (76.6%) and with self-support (74.9%). Details about the demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients on ART (N=351)

| Patient characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 125 (35.6) |

| Female | 226 (64.4) |

| Age | |

| 18–30 | 95 (27.1) |

| 31–45 | 134 (38.2) |

| 46–64 | 122 (34.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Unmarried | 53 (15.1) |

| Married | 175 (49.9) |

| Divorced | 76 (21.7) |

| Widowed | 47 (13.4) |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox | 307 (87.5) |

| Islam | 37 (10.5) |

| Protestant | 5 (1.4) |

| Catholic | 2 (0.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Amhara | 327 (93.2) |

| Tigre | 16 (4.6) |

| Others | 8 (2.3) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 255 (72.6) |

| Unemployed | 96 (27.4) |

| Monthly income | |

| No income | 44 (12.5) |

| Less than 500 | 118 (33.6) |

| 501–1,500 | 133 (37.9) |

| Above 1,500 | 56 (16.0) |

| Educational level | |

| Illiterate | 66 (18.6) |

| Basic education | 22 (6.3) |

| Elementary | 109 (31.1) |

| Secondary | 72 (20.5) |

| College diploma and above | 82 (23.4) |

| Living condition | |

| Living alone | 74 (21.1) |

| Living with family | 269 (76.6) |

| Living with friend | 3 (0.9) |

| Living with others | 5 (1.4) |

| Source of support | |

| Self-support | 263 (74.9) |

| Families | 78 (22.2) |

| NGOs | 10 (2.8) |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; NGOs, nongovernmental organizations.

Attitude toward ART

From the total of 351 respondents, 232 (66.1%) strongly agreed that ART drug is essential for their life, and 281 (80.1%) were comfortable, 42 (11.9%) neither comfortable nor uncomfortable, and 18 (8%) uncomfortable to take ART medications in the presence of others. Approximately 327 (93.2%) respondents disclosed their HIV sero-status to family members, whereas 249 (70.9%) disclosed their HIV status to community. Seventy-nine (22.5%) respondents were active substance users (active substance is any of the substance of abuse including cigarette, khat, alcohol, or any other that could affect the adherence and treatment outcome of HAART) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Attitude of PLWHA toward ART (N=351)

| Patient characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| ART is essential for the HIV patient | |

| Strongly agree | 232 (66.1) |

| Agree | 108 (30.8) |

| Uncertain | 8 (2.3) |

| Disagree | 3 (0.9) |

| Are you feeling comfortable to take ART in the presence of others | |

| Comfortable | 281 (80.1) |

| Uncomfortable | 28 (8.0) |

| Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable | 42 (11.9) |

| Family disclosure | |

| Yes | 327 (93.2) |

| No | 24 (6.8) |

| Community disclosure | |

| Yes | 249 (70.9) |

| No | 102 (29.1) |

| Use of active substance | |

| Yes | 79 (22.5) |

| No | 272 (77.5) |

Abbreviations: PLWHA, people living with HIV/AIDS; ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

Adherence with ART and respondents’ satisfaction

As shown in Table 3, 36 (10.3%) began ART within the last 6 months, 44 (12.5%) in the last 6 months to 1 year, 79 (22.5%) respondents started ART in the last 1–3 years, and 192 (54.7%) began after more than 3 years. Concerning drug’s side effects, 186 (53%) respondents reported that they had encountered side effects using ART. Approximately 178 (50.7%) respondents were not well satisfied with the health care providers’ services, and only 4.3% of the respondents were satisfied with the health care providers all the time. Sixty-seven (19.1%) respondents missed at least one dose in the previous 1 month, of whom eleven (16.4%) doubled the dose, 22 (32.8%) waited for the next dose, and 34 (50.8%) took medicines immediately they remembered, as a means to handle the missing dose. The majority of respondents (97.2%) were found to have either fair or good adherence.

Table 3.

Treatment adherence and satisfaction with ART (N=351)

| Patient characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Duration of therapy | |

| <6 months | 36 (10.3) |

| 6–12 months | 44 (12.5) |

| >12 months to 3 years | 79 (22.5) |

| >3 years | 192 (54.7) |

| Side effect | |

| Yes | 186 (53) |

| No | 165 (47) |

| Satisfaction with health care provider | |

| Most of the time | 50 (14.2) |

| Sometimes | 108 (30.8) |

| None of the time | 178 (50.7) |

| All the time | 15 (4.3) |

| Dose missed? | |

| Yes | 67 (19.1) |

| No | 284 (80.9) |

| Number of missed doses | |

| 1–3 doses | 38 (56.7) |

| 4–8 doses | 19 (28.4) |

| >8 doses | 10 (14.9) |

Abbreviation: ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Reasons for non-adherence

The reasons that respondents reported missing their doses were forgetfulness 29 (43.3%), missing appointment 14 (20.9%), having run out of medicines 9 (13.4%), depression, anger, or despair 4 (6.0%), side effects 2 (3.0%), and a bad attitude toward ART (patients did not think that the medicine helped) 2 (3.0%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reasons given for missing the ART medication doses among PLWHA in Gondar (N=67).

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; PLWHA, people living with HIV/AIDS; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

Based on the binary logistic analysis output, age (P-value 0.017), employment (P-value 0.02), HIV disclosure (P-value 0.04), and comfortability to take ART in the presence of others (P-value 0.02) were variables found to be significantly associated with non-adherence. The likelihood of ART non-adherence in the age group 31–45 years and 18–30 years was 1.51 (OR; 95% confidence interval 1.20–1.82) and 0.63 (OR; 95% confidence interval 0.35–0.91) times that of the age group 46–64 years, respectively. The likelihood of ART non-adherence in the employed patients was 0.41 times that of the unemployed. The likelihood of ART non-adherence in the PLWHA, who disclosed HIV status to family, was 0.48 times more than those who did not disclose. The likelihood of ART non-adherence among PLWHA who were comfortable taking ART in the presence of others was 3.97 times that of those who were not comfortable (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with non-adherence to ART (N=351)

| Variable | Adherence level

|

OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherent | Non-adherent | |||

| Age | ||||

| 18–30 | 82 (86%) | 13 (14%) | 0.63 (0.35, 0.91) | 0.017 |

| 31–45 | 101 (75%) | 33 (25%) | 1.51 (1.20, 1.82) | |

| 46–64 | 101 (82.8%) | 21 (17.2%) | 1 | |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed | 200 (78.4%) | 55 (21.6%) | 0.41 (0.20, 0.88) | 0.02 |

| Unemployed | 84 (87.5%) | 12 (12.5%) | 1 | |

| HIV disclosure (family) | ||||

| Disclosed | 265 (81%) | 62 (19%) | 0.48 (0.23, 0.98) | 0.04 |

| Undisclosed | 19 (79.2%) | 5 (20.8%) | 1 | |

| Comfortability to take ART in the presence of others | ||||

| Comfortable | 234 (83.3%) | 47 (16.7%) | 3.97 (1.17, 13.50) | 0.02 |

| Uncomfortable | 23 (82.1%) | 5 (17.9%) | 1 | |

| Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable | 27 (64.3%) | 15 (35.7%) | 0.56 (0.23, 0.89) | |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Discussion

With the growing global prevalence of many chronic diseases, adherence-related problems are expected to worsen, as predicted by World Health Organization.26 Adherence rates in PLWHA are usually reported as the percentage of the prescribed doses of the HAART medications actually taken by the patient over a specified period. Maintaining an adherence greater than 95% is mandatory in HIV patients, although adherence data are often presented as dichotomous variables (adherence versus non-adherence).27 Monitoring and supporting adherence are of high importance for successful HIV treatment. At least 95% ART adherence is required to suppress viral replication, show clinical improvement, and increase the CD4 count.28 If this adherence level is not maintained, then it will lead to poor treatment outcome. The current study revealed the adherence rate to be 80.9%, which is higher than ideal African adherence rate of 77%29 and comparable with the other studies.18,21,30

In our sample, the females (64.4%) were more in number than males, which is similar to that of other studies.24,30 Further, the HIV prevalence in women (1.9%) is higher than in men (1%) in Ethiopia.31 The study showed that the majority of the participants were married (49.9%) followed by divorced (21.7%). This finding raises a need of more efforts to be geared toward partners’ testing and disclosure to avoid marital HIV infections in discordant couples and to fight any stigma at home.32 The results from this study demonstrated that age, the level of education achieved, employment or nonemployment, HIV disclosure to family, and comfortability in taking ART in the presence of others are the conditions that will effect ART adherence. This is contradictory to the finding of Maqutu et al.33 However, demographic factors are closely linked to socioeconomic status, which encompasses access to resources such as educational opportunities, living conditions, social support, and health facilities, which are similarly observed in the literature of Rachlis et al’s review on livelihood and ART adherence at its early stage.34

Educational level and income were the two most frequently studied livelihood factors to be the determinants for self-efficacy, which shows that one can successfully assess a specific behavior.35 Studies showed that support from the family and supporting PLWHA were predictors of ART adherence.36,37 In this study, 74.9% of the respondents were self-supporting, while only 22.8% had support from family and 2.8% from nongovernmental organizations. A study conducted in Zambia showed that patient-related factors facilitating adherence included looking and feeling better, the support from patients’ family, and physical reminders.38 For adherence counseling, family or community members should be engaged to build support, and this implies that self-supporting alone may also be a factor to increase the uptake of ART medication; support from family, friends, nongovernmental organizations, and other groups for PLWHA also needs to be emphasized.39

The attitude of PLWHA about ART is detrimental to the treatment outcome. A patient’s positive attitude will ensure that the patient adheres to ART and so a better outcome can be achieved.21 From the total respondents, approximately 97% of them agreed and strongly agreed that the use of ART is essential to their life. Approximately 80% of the patients were comfortable to take ART in the presence of others. These results were higher than that of the Yirgalem study (26.8%) but lower when compared to the previous study from Gondar (97.2%).21,23 In this study, 93.2% disclosed their HIV sero-status to family members and 70.9% to the community, which helped the patient to take medication openly and in the presence of others. So, encouraging voluntary HIV status disclosure in a community with access to ART may help to decrease stigma and improve adherence. Further, 23% of the patients took active substances regularly, which is much higher than studies previously reported from Gondar (3.2%)23 and Wolaita (3.6%),24 which may be one of the reasons for more patients to miss doses.40

The risk of poor adherence increases with the duration and complexity of treatment regimen, and both long duration and complex treatment are inherent in chronic illnesses. The respondents’ adherence rate was inversely proportional to the length of time they had been on ART. The longer they were on ART, the lesser they adhered. A similar trend was observed in the other African studies, during early therapy before they developed long-term adverse effects and dramatic increase in their health.30

In this study, more than half (50.7%) of the respondents were not satisfied with health care providers, and the reasons were not clearly disclosed. Lack of respectful treatment, confidentiality, health care access, communication barrier, and poor information given to patients were some of the reasons disclosed by the PLWHA, as being associated with non-adherence to ART.

This is consistent with a previous study, which reported that poor self-reported access to medical care is strongly associated with HIV stigma and PLWHA, who experience stigmatization. They might perceive more difficulty accessing care. Fear of rejection and discrimination may lead to a perception that the health care setting is intolerant and inaccessible.12 The health care system needs to improve patients’ confidence, trust, and satisfaction with their relationship with health care providers. This is specifically true, as participants have indicated. The system will thrive only if the patients perceive that it is a confidential service and that the problems of access and assistance with their needs are eliminated.

Forgetfulness, missing appointment, and running out of medicine were the most common reasons for poor adherence to medications in this study. Similar reasons were reported in the studies conducted in Yirgalem Hospital, Gondar, and Harari in Ethiopia and in South Africa and Guatemala.21,23,30,33,36 Further, our study also identifies that more important determinants, health care facilities and providers, influence an adherence to ART.

Binomial logical regression has revealed that age, employment, HIV disclosure, and being comfortable to take ART in the presence of others all have a significant association with ART adherence. These findings are logical in the sense that patients who disclosed their HIV status to family members can get more support and help from them. Unemployed patients are more likely to be depressed and less likely to socialize, leading to miss appointments and access to health care. HIV disclosure was one of the significant factors observed in Gondar and Wolaita studies.23,24 Further, unemployment was found to be significantly associated with non-adherence in the Brazilian study.17

Our measurement of adherence was only based on patients’ self-report. This may be subject to social desirability, inaccurate memory, and recall bias. Despite the perceived limitations, many clinicians and researchers alike continue to rely extensively on self-report adherence measures, probably because they continue to be the least costly and burdensome way to assess ART adherence.

Conclusion

Forgetfulness was the most common reason for poor adherence to the medication. As the non-adherence is a multidimensional problem, tailored counseling interventions, targeted at the underlying cause of non-adherence, seems an attractive method for supporting PLWHA with their use of ART drugs. Interventions addressing this type of non-adherence may need to focus on simplifying the regimen, providing reminders to the patients to take their medications, and supporting patients in making the intake of medication part of their daily routine.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to thank University of Gondar hospital and the ART center for providing their support in fulfilling this research project. They also extend their heartfelt thanks to Ms Rosalind Schogger for her help in the English language editing of the manuscript.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Author contributions

BT contributed to the study design, conception, literature review, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. AS and ZS contributed to the study design, data collection, manuscript writing, and analysis and interpretation of the data. All the authors critically revised the manuscript, have given final approval to the version published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.MOH/HAPCO . HIV/AIDS Estimates and Projections in Ethiopia, 2011–2016. Addis Ababa, ET: Health Programs Department, HAPCO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erah PO, Arute JE. Adherence of HIV/AIDS patients to antiretroviral therapy in a tertiary health facility in Benin City. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;2(7):145–152. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO/UNAID . Progress on Global Access to HIV Antiretroviral Therapy; a Report on 3″ by 5″ and Beyond Geneva, World Health Organization/United Nation Joint Programmed on AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health, Ethiopia . Guidelines for Management of OPI Antiretroviral Treatment in Adolescents and Adults in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, ET: MOH; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO/HIV/AIDS Programme . HIV Drug Resistance: Fact Sheet. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apisarnthanarak A, Mundy LM. Long-term outcomes of HIV infected patients with <95% rates of adherence to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(1):115–117. doi: 10.1086/653445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chesney MA. Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(2):171–176. doi: 10.1086/313849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg KM, Demas PA, Howard AA, Schoenbaum EE, Gourevitch MN, Arnsten JH. Gender differences in factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1111–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kempf M, Pisu M, Dumcheva A, Westfall A, Md J, Saag M. Gender differences in discontinuation of antiretroviral treatment regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(3):336–341. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b628be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holzemer WL, Uys LR. Managing AIDS stigma. SAHARA J. 2004;1(3):165–174. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2004.9724839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, Martins D, Cunningham WE. The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1101–1108. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1068-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyimo RA, Stutterheim SE, Hospers HJ, de Glee T, van der Ven A, de Bruin M. Stigma, disclosure, coping and medication adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS in Northern Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(2):98–105. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiMatteo MR, Haskard-Zolnierek KB, Martin LR. Improving patient adherence: a three-factor model to guide practice. Health Psychol Rev. 2012;6(1):74–91. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penn C, Watermeyer J, Evans M. Why don’t patients take their drugs? The role of communication, context and culture in patient adherence and the work of the pharmacist in HIV/AIDS. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(3):310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eliud W. ART Adherence in Resource Poor Settings in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multidisciplinary Review. Rockville, MD: AIDS INFO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonolo Pde F, César CC, Acúrcio FA, et al. Non-adherence among patients initiating antiretroviral therapy: a challenge for health professionals in Brazil. AIDS. 2005;19(suppl 14):s5–s13. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191484.84661.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nachega JB, Stein DM, Lehman DA, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults in Soweto, South Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20(10):1053–1056. doi: 10.1089/aid.2004.20.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MOH/HAPCO . Guidelines for Management of Opportunistic Infections and Anti Retroviral Treatment in Adolescents and Adults in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, ET: MOH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Murri R, AdICoNA Study Group et al. Correlates and predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: overview of published literature. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31:123–127. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212153-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endrias M, Alemayehu W, Gail D. Adherence to ART in PLWHA at Yirgalem Hosptial, South Ethiopia. Ethio J Health Dev. 2008;22(2):174–179. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayele T, Tefera B, Fisehaye A, Sibhatu B. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV/AIDS in resource-limited setting of southwest Ethiopia. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tessema B, Biadglegne F, Mulu A, Getachew A, Emmrich F, Sack U. Magnitude and determinants of non-adherence and non-readiness to highly active antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV/AIDS in Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amsalu A, Wanzahun G, Mohammed T, Tariku D. Factors associated with antiretroviral treatment adherence among adult patients in Wolaita Soddo Hospital, Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Sci J Pub Health. 2014;2(2):69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 25.UNFPA . Summary and Statistical Report of the 2012 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. Ethiopia: UNFPA; 2012. pp. 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization . Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medications. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bangsberg DR. A paradigm shift to prevent HIV drug resistance. PLoS Med. 2008;5(5):e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;296(6):679–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Habtamu M, Tekabe A, Zelalem T. Factors Affecting Adherence to Antiretroviral Treatment in Harari National Regional State. Vol. 2013. Eastern Ethiopia: ISRN AIDS; 2013. p. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MOH/HAPCO . National HIV/AIDS Estimates in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, ET: MOH; 2012. p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dlamini PS, Wantland D, Makoae LN, et al. HIV stigma and missed medications in HIV-positive people in five African countries. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(5):377–387. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maqutu D, Zewotir T, North D, Naidoo K, Grobler A. Factors affecting first-month adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive adults in South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2010;9(2):117–124. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2010.517478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rachlis BS, Mills EJ, Cole DC. Livelihood security and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low and middle income settings: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):6–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barclay TR, Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, et al. Age-associated predictors of medication adherence in HIV positive adults: health beliefs, self-efficacy, and neuro-cognitive status. Health Psychol. 2007;26(1):3–7. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell JI, Ruano AL, Samayoa B, EstradoMuy DL, Arathoon E, Young B. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in an urban, free-care HIV clinic in Guatemala city, Guatemala. J Int Asso Phy AIDS Care. 2010;9(6):390–395. doi: 10.1177/1545109710369028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amberbir A, Woldemichael K, Getachew S, Girma B, Deribe K. Prediction of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons: a prospective study in southwest Ethiopia. BMC Pub Health. 2008;8:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant E, Logie D, Masura M, Gorman D, Murray SA. Factors facilitating and challenging access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a township in the Zambian Copperbelt. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1155–1160. doi: 10.1080/09540120701854634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO/HIV/AIDS Programme . Strengthening Health Services to Fight HIV/AIDS: ANTIRETROVIRAL Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: Recommendation for a Public Health Approach. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehavot K, Huh D, Walters KL, King KM, Andrasik MP, Simoni JM. Buffering effects of general and medication-specific social support on the association between substance use and HIV medication adherence. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(3):186–187. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, Martins D, Cunningham WE. The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1101–1108. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1068-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]