Abstract

Purpose

Nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy is common and is associated with increased prescription copayment amount and black race. Studies suggest that household wealth may partly explain racial disparities. We investigated the impact of net worth on disparities in adherence and discontinuation.

Patients and Methods

We used the OptumInsight insurance claims database to identify women older than age 50 years diagnosed with early breast cancer, from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2011, who were using hormonal therapy. Nonadherence was defined as a medication possession ratio of ≤ 80% of eligible days over a 2-year period. We evaluated the association of demographic and clinical characteristics, annual household income, household net worth (< $250,000, $250,000 to $750,000, or > $750,000), insurance type, and copayments (< $10, $10 to $20, or > $20) with adherence to hormonal therapy. Logistic regression analyses were conducted by sequentially adding sociodemographic and financial variables to race.

Results

We identified 10,302 patients; 2,473 (24%) were nonadherent. In the unadjusted analyses, adherence was negatively associated with black race (odds ratio [OR], 0.76; P < .001), advanced age, comorbidity, and Medicare insurance. Adherence was positively associated with medium (OR, 1.33; P < .001) and high (OR, 1.66; P < .001) compared with low net worth. The negative association of black race with adherence (OR, 0.76) was reduced by adding net worth to the model (OR, 0.84; P < .05). Correcting for other variables had a minimal impact on the association between race and adherence (OR, 0.87; P = .08). The interaction between net worth and race was significant (P < .01).

Conclusion

We found that net worth partially explains racial disparities in hormonal therapy adherence. These results suggest that economic factors may contribute to disparities in the quality of care.

INTRODUCTION

Lack of compliance (early discontinuation and/or nonadherence) with medications is a well-known problem in the medical literature.1–3 Oral hormonal therapy for the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer (BC) results in a reduction in BC recurrence,4 and for women at high risk for BC, these medications result in a 50% reduction in the incidence of new BCs.5 Despite its efficacy, approximately 7% to 10% of patients discontinue therapy annually,6–11 with only approximately 50% of patients completely finishing their recommended 5-year course. This nonadherence reduces the potential survival benefits associated with hormonal therapy.12–15 Our work, and work by other researchers, suggests that patient race is one of several factors that is associated with nonadherence.6,10,16,17 Treatment-related factors may partially explain the racial differences in BC survival outcomes.18

Another factor that affects adherence is out-of-pocket costs. In a prior study by our group, we found that higher copayment amounts were inversely associated with adherence to adjuvant aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy.19 In addition, we demonstrated that shifts in use from brand name to generic AIs were associated with decreased discontinuation and increased adherence to hormonal therapy that persisted after controlling for copayment amount.20 Finally, we found that women with high income were more likely to be adherent than women with low income despite controlling for other factors.20

Compared with white women, BC incidence is lower among black women, but mortality is approximately 40% higher.21 Interestingly, the racial disparity in mortality began in the 1980s and has continued to increase since that time. This disparity coincides with an increased understanding of the importance of adjuvant treatment and suggests that this disparity is modifiable.22 Studies suggest that black women more often do not receive timely treatment compared with white women,23 are less likely to receive optimal systemic adjuvant therapy than white women,24,25 and are more likely to have delays in the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, all of which are associated with worse survival.26,27

In studies of patients without cancer, there is a suggestion that disparities in wealth may contribute to health disparities between racial/ethnic groups. An analysis from the Consumer Finance and Health Retirement Survey demonstrated that blacks and Hispanics have, on average, significantly lower net worth compared with whites. Participants in the lowest net worth quartile had a three to five times higher odds of reporting fair or poor health status compared with those in the highest net worth quartile.28 No studies have examined the influence of net worth on quality of care in patients with cancer. We investigated the contribution of net worth to explaining racial disparities in adherence to hormonal therapy among women with early-stage BC.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Source

We used the OptumInsight insurance claims database to identify a cohort of women with BC who were receiving hormonal therapy. OptumInsight maintains a proprietary research database containing claims, membership, provider, and ancillary data for over 36 million members. These include 25 million commercial members from UnitedHealthcare and six million Medicare managed care members. Membership and provider records are linked to pharmacy claims and medical claims, including diagnosis and procedure codes (Current Procedural Terminology, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, procedures) with their dates of service and providers. The OptumInsight database provides information on each prescription filled, including the drug, the prescriber and his/her medical specialty, the out-of-pocket payment, and the prescription copayment amount.

Sample Selection

We identified all women who had a diagnosis of nonmetastatic invasive BC and who were continuously enrolled 12 months before and 12 months after the diagnosis date (2007 to 2011). We restricted our sample to patients who had a prescription claim for hormonal therapy (AIs or tamoxifen) with a diagnosis of BC in the 6 months before the first hormone therapy prescription and who were at least 50 years of age at the time of the initial prescription.

Demographic Characteristics

Age at hormone therapy initiation was categorized as 50 to 55, 56 to 65, 66 to 74, and ≥ 75 years. Race was classified as white, black, Asian, or Hispanic by self-report. In addition, patients were categorized by geographic region, education (< or ≥ high school), and year of hormone therapy initiation (2007 to 2011).

Comorbid Disease

To assess the prevalence of comorbid disease in our cohort, we used the episode treatment groups method.29,30 This methodology uses an algorithm to compile clinical information, including prescriptions and claims for medical encounters, into episodes of care that can then be used to create a metric for chronic disease comorbidity. Patients were categorized as having one to five or ≥ six comorbid conditions.

Clinical Characteristics

For each patient, we determined the specialty of the provider who prescribed hormonal therapy most frequently, categorizing the physician as medical oncologist or primary care physician/surgical oncologist. Surgery was classified as mastectomy or lumpectomy.

Financial Factors

The copayment for the hormonal therapy was the amount paid by a subscriber for a 30-day prescription. Copayments for 60- or 90-day prescriptions were adjusted to 30-day copayment amounts. Copayment was categorized as less than $10, $10 to $20, or more than $20 based on common copayment amounts (multiples of $5), and so there was a roughly even distribution across the patient population. Coverage type was categorized as commercial or Medicare. The number of patients on Medicaid was low; therefore, these patients were excluded from the analysis.

We categorized annual household income as < $40,000, $40,000 to $99,999, and ≥ $100,000 and net worth as < $250,000, $250,000 to $749,999, and ≥ $750,000. We constructed the three-level categories based on sample size and natural cutoff values. OptumInsight uses a major data syndicator, Knowledge-Based Marketing Solutions (KBM, Richardson, TX), which is linked to participants in OptumInsight by name, date of birth, address, and phone number. KBM collects data from primary sources, including public records, purchase transactions, census data, and consumer surveys. An algorithm for the estimation of net worth was created by KBM and validated against a data set with known net worth using a multivariable predictive model that included Internal Revenue Service data (investments, average refund, and average savings), mortgage loan–to–home value ratio, balance to credit limits on credit cards, number of open bank cards with balances, and aggregated credit. Net worth was the only estimated variable.

Outcomes

We categorized patients as having discontinued therapy if the calculated drug supply, based on the last prescription date plus any surplus from a prior prescription, indicated a minimum 45-day supply gap with no hormone therapy on hand. Adherence was determined by the medication possession ratio (MPR) (ie, the number of pills supplied over a fixed period of time) between the first and the last prescription over a maximum 2-year period.31 We categorized patients as being adherent if the MPR was ≥ 80%.

Follow-Up and Censoring

All patients were followed for up to 2 years. The median length of follow-up was 691 days for those with a drug supply of ≤ 2 years (n = 7,650). Follow-up was available through December 31, 2012. We censored patients at the date at which they disenrolled from their health plan or at the end of the study period.

Statistical Analysis

We compared the demographic, clinical, and economic characteristics of black and white patients, patients in the three net worth groups, and adherent and nonadherent patients, using overall χ2 tests. We then determined the unadjusted adherence rates for each of the characteristics. Similar analyses were conducted for early discontinuation.

We used multivariable logistic regression models to analyze the association between net worth and hormonal therapy adherence, classified as a dichotomous variable (MPR ≥ v < 80%). All variables were included that had an unadjusted association of P < .05. To assess whether racial differences in adherence were explained by covariates, each variable was screened individually in the multivariable model along with race. The association between race and adherence was assessed after the addition of financial, demographic, and clinical factors. A stratified multivariable analysis by each net worth category was also performed, as was a formal test for interaction. We examined multicollinearity in our models using the link test for postestimation.

We used multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate the association between net worth and hormonal therapy discontinuation controlling for clinical, financial, and demographic factors. We estimated Kaplan-Meier survival curves for time to discontinuation by net worth category. The assumption of proportionality was confirmed visually. For all models, we rejected the null hypothesis at the P < .05 level of significance. All analyses were conducted using STATA version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We identified 10,302 patients who initiated hormonal therapy; 2,473 (24%) were nonadherent during the study period. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the total cohort. The mean age of patients at the time of BC diagnosis in our study was 61 years. The majority of the study cohort identified themselves as white (79.2%), followed by black (9.2%) and Hispanic (5.8%). The majority of patients had commercial insurance (95.8%). Of the patients in this cohort, 3,358 (33%) had low net worth, 4,982 had medium net worth (48%), and 1,935 (19%) had high net worth. Black patients, compared with white patients, were less likely to be adherent (71.2% v 76.6%, respectively), less likely to have high net worth (4.4% v 20.5%, respectively), more likely to have a higher copayment (42.5% v 38.4%, respectively), and more likely to have a low income (43% v 18%, respectively). Net worth was significantly associated with all of the covariates we assessed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Diagnosed With Localized Breast Cancer Who Received Adjuvant HT, Overall and by Net Worth Category

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 10,302) |

Patients With Low Net Worth (< $250,000; n = 3,385) |

Patients With Medium Net Worth ($250,000-$750,000; n = 4,982) |

Patients With High Net Worth (> $750,000; n = 1,935) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Adherence | ||||||||

| Yes | 7,829 | 76.0 | 2,427 | 71.7 | 3,839 | 77.1 | 1,563 | 80.8 |

| No | 2,473 | 24.0 | 958 | 28.3 | 1,143 | 22.9 | 372 | 19.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 8,158 | 79.2 | 2,409 | 71.2 | 4,079 | 81.9 | 1,670 | 86.3 |

| Black | 952 | 9.2 | 543 | 16.0 | 367 | 7.4 | 42 | 2.2 |

| Hispanic | 595 | 5.8 | 286 | 8.5 | 238 | 4.8 | 71 | 3.7 |

| Asian | 222 | 2.2 | 55 | 1.6 | 101 | 2.0 | 66 | 3.4 |

| Other/unknown | 375 | 3.6 | 92 | 2.7 | 197 | 4.0 | 86 | 4.4 |

| Region | ||||||||

| Northeast | 1,019 | 9.9 | 265 | 7.8 | 493 | 9.9 | 261 | 13.5 |

| West | 2,549 | 24.8 | 821 | 24.3 | 1,355 | 27.2 | 373 | 19.3 |

| Midwest | 4,871 | 47.3 | 1,808 | 53.5 | 2,318 | 46.6 | 745 | 38.5 |

| South | 1,855 | 18.0 | 488 | 14.4 | 812 | 16.3 | 555 | 28.7 |

| Net worth | ||||||||

| Low (< $250,000) | 3,385 | 33.0 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Medium ($250,000-$750,000) | 4,982 | 48.0 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| High (> $750,000) | 1,935 | 19.0 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Household income | ||||||||

| Low (< $40,000) | 2,129 | 20.7 | 1,841 | 54.4 | 288 | 5.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Medium ($40,000-$100,000) | 5,812 | 56.4 | 1,538 | 45.4 | 4,085 | 82.0 | 189 | 9.8 |

| High (> $100,000) | 2,361 | 22.9 | 6 | 0.2 | 609 | 12.2 | 1,746 | 90.2 |

| Adjusted 30-day copay | ||||||||

| < $10 | 3,315 | 32.2 | 1,035 | 30.6 | 1,654 | 33.2 | 626 | 32.4 |

| $10-$20 | 3,006 | 29.2 | 977 | 28.9 | 1,449 | 29.1 | 580 | 29.9 |

| > $20 | 3,981 | 38.6 | 1,373 | 40.6 | 1,879 | 37.7 | 729 | 37.7 |

| Medicare | ||||||||

| Yes | 435 | 4.2 | 182 | 5.49 | 208 | 4.2 | 45 | 4.2 |

| No | 9,867 | 95.8 | 3,203 | 4.6 | 4,774 | 95.8 | 1,890 | 97.7 |

| Education | ||||||||

| < High school | 2,824 | 27.4 | 2,831 | 54.1 | 979 | 19.7 | 14 | 0.7 |

| > High school | 7,478 | 72.6 | 1,554 | 45.9 | 4,003 | 80.3 | 1,921 | 99.3 |

| Age at HT initiation, years | ||||||||

| 50-55 | 2,986 | 29.0 | 1,074 | 31.7 | 1,425 | 28.6 | 487 | 25.2 |

| 56-65 | 5,213 | 50.6 | 1,591 | 47.0 | 2,570 | 51.6 | 1,052 | 54.4 |

| 66-75 | 1,398 | 13.6 | 449 | 13.3 | 669 | 13.4 | 280 | 14.5 |

| ≥ 75 | 705 | 6.8 | 271 | 8.0 | 318 | 6.4 | 116 | 6.0 |

| Year of HT initiation | ||||||||

| 2007 | 1,490 | 14.5 | 471 | 13.9 | 708 | 14.2 | 311 | 16.1 |

| 2008 | 2,757 | 25.8 | 927 | 27.4 | 1,229 | 24.7 | 501 | 25.9 |

| 2009 | 2,655 | 25.8 | 835 | 24.7 | 1,305 | 26.2 | 515 | 26.6 |

| 2010 | 2,487 | 24.1 | 83 | 24.6 | 1,227 | 24.6 | 427 | 22.1 |

| 2011 | 1,013 | 9.8 | 319 | 9.4 | 513 | 10.3 | 181 | 9.4 |

| Mastectomy | ||||||||

| No | 5,128 | 49.8 | 1,567 | 46.3 | 2,543 | 51.0 | 1,018 | 52.6 |

| Yes | 5,174 | 50.2 | 1,818 | 53.7 | 2,439 | 49.0 | 917 | 47.4 |

| No. of comorbidities | ||||||||

| 1-5 | 8,282 | 80.4 | 2,642 | 78.1 | 4,020 | 80.7 | 1,620 | 83.7 |

| ≥ 6 | 2,020 | 19.6 | 743 | 21.9 | 962 | 19.3 | 315 | 16.3 |

| Provider specialty | ||||||||

| Hematology-oncology | 7,389 | 71.7 | 2,403 | 71.1 | 3,600 | 72.3 | 1,384 | 71.5 |

| Other | 2,913 | 28.3 | 980 | 28.9 | 1,382 | 27.7 | 551 | 28.5 |

Abbreviation: HT, hormonal therapy.

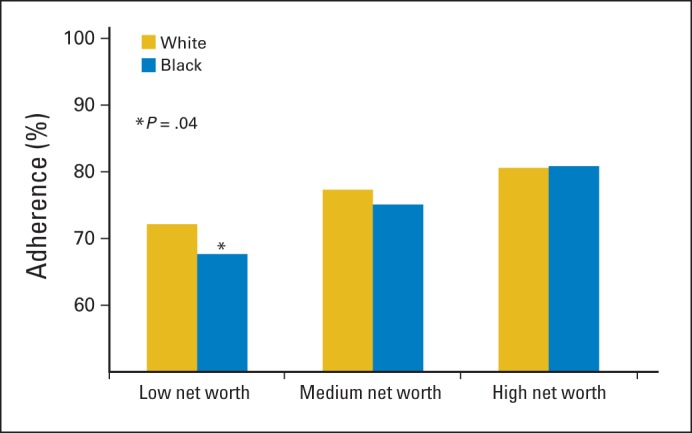

In the unadjusted analyses, adherence was negatively associated with black race (odds ratio [OR], 0.76; 95% CI, 0.55 to 0.88), advanced age, comorbidity, and Medicare insurance (OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.45 to 0.67). Adherence was positively associated with medium net worth (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.20 to 1.46) and high net worth (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.45 to 1.90) compared with low net worth (Table 2). In an adjusted logistic regression analysis, black patients were no longer less likely to be adherent with hormonal therapy (OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.01) compared with white patients (Table 2). Women with a medium household net worth (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.43) and a high household net worth (OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.36 to 1.84) were also more likely to be adherent with hormonal therapy compared with those with a low net worth. Medicare patients were also less likely to be adherent (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.72) compared with patients with commercial insurance. Patients with increased comorbid conditions and increased age had significantly lower odds of adherence. In the adjusted model, income was no longer significant after controlling for net worth, so it was removed as a result of the strong correlation with net worth (r = 0.8). The interaction between race and net worth was significant, with no significant association of race in the medium and high net worth groups and a significant association in the low net worth group (P < .01). A stratified analysis by net worth confirmed that lower adherence was seen among black women in the low net worth group (OR, 0.81; P < .046), whereas no association was observed between black race and adherence in the medium and high net worth groups (Fig 1).

Table 2.

Adherence (medication possession ratio ≥ 80%) of Patients Diagnosed With Localized Breast Cancer at Age ≥ 50 Years Who Received Adjuvant HT

| Factor | Adherent (n = 7,829) |

Nonadherent (n = 2,473) |

P* | Unadjusted OR |

Multivariable Analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Race/ethnicity | < .001 | ||||||||

| White | 6,247 | 76.6 | 1,911 | 23.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Black | 678 | 71.2 | 274 | 28.8 | 0.76 | 0.55 to 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.74 to 1.01 | |

| Hispanic | 430 | 72.3 | 165 | 27.7 | 0.74 | 0.55 to 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.62 to 1.16 | |

| Asian | 182 | 82.0 | 40 | 18.0 | 1.29 | 0.85 to 1.97 | 1.38 | 0.90 to 2.11 | |

| Other | 292 | 77.9 | 83 | 22.1 | 1.07 | 0.84 to 1.38 | 1.03 | 0.80 to 1.32 | |

| Region | < .001 | ||||||||

| Northeast | 831 | 81.6 | 188 | 18.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| West | 1,988 | 80.0 | 561 | 20.0 | 0.67 | 0.55 to 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.57 to 0.84 | |

| Midwest | 3,619 | 74.3 | 1,252 | 25.7 | 0.80 | 0.67 to 0.96 | 0.81 | 0.67 to 0.98 | |

| South | 1,387 | 74.8 | 468 | 25.2 | 0.65 | 0.55 to 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.57 to 0.81 | |

| Net worth | < .001 | ||||||||

| Low (< $250,000) | 2,427 | 71.7 | 958 | 28.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Medium ($250,000-$750,000) | 3,839 | 77.1 | 1,143 | 22.9 | 1.33 | 1.20 to 1.46 | 1.29 | 1.15 to 1.43 | |

| High (> $750,000) | 1,563 | 80.8 | 372 | 19.2 | 1.66 | 1.45 to 1.90 | 1.59 | 1.36 to 1.84 | |

| Household income | < .001 | ||||||||

| Low (< $40,000) | 1,544 | 72.5 | 585 | 27.5 | 1.0 | — | |||

| Medium ($40,000-$100,000) | 4,405 | 75.8 | 1,407 | 24.2 | 1.19 | 1.05 to 1.32 | — | ||

| High (> $100,000) | 1,880 | 79.7 | 481 | 20.4 | 1.48 | 1.29 to 1.70 | — | ||

| Adjusted 30-day copay | < .001 | ||||||||

| < $10 | 2,574 | 77.7 | 741 | 22.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| $10-$20 | 2,311 | 76.9 | 695 | 23.1 | 0.96 | 0.85 to 1.08 | 0.99 | 0.88 to 1.10 | |

| > $20 | 2,944 | 74.0 | 1,037 | 26.0 | 0.82 | 0.73 to 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.80 to 1.01 | |

| Medicare | < .001 | ||||||||

| No | 7,550 | 76.5 | 2,317 | 23.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 279 | 64.1 | 156 | 35.9 | 0.55 | 0.45 to 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.46 to 0.72 | |

| Education | .009 | ||||||||

| < High school | 2,095 | 74.2 | 729 | 25.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| > High school | 5,734 | 76.7 | 1,744 | 23.3 | 1.14 | 1.04 to 1.26 | 0.94 | 0.84 to 1.06 | |

| Age at HT initiation, years | .001 | ||||||||

| 50-55 | 2,219 | 74.3 | 767 | 25.7 | 0.85 | 0.75 to 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.77 to 0.95 | |

| 56-65 | 4,031 | 77.3 | 1,182 | 22.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| 66-75 | 1,072 | 76.7 | 326 | 23.3 | 0.96 | 0.84 to 1.11 | 1.08 | 0.93 to 1.26 | |

| ≥ 75 | 507 | 71.9 | 198 | 28.1 | 0.75 | 0.63 to 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.73 to 1.07 | |

| Year of HT initiation | < .001 | ||||||||

| 2007 | 1,094 | 73.4 | 396 | 26.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| 2008 | 1,956 | 73.6 | 701 | 26.4 | 1.01 | 0.87 to 1.17 | 1.03 | 0.89 to 1.20 | |

| 2009 | 1,992 | 75.0 | 663 | 25.0 | 1.09 | 0.94 to 1.26 | 1.10 | 0.95 to 1.28 | |

| 2010 | 1,962 | 78.9 | 525 | 21.1 | 1.35 | 1.16 to 1.57 | 1.36 | 1.17 to 1.59 | |

| 2011 | 825 | 81.4 | 188 | 18.6 | 1.59 | 1.31 to 1.93 | 1.54 | 1.26 to 1.89 | |

| Mastectomy | .356 | ||||||||

| No | 3,877 | 75.6 | 1,251 | 24.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 3,952 | 76.4 | 1,222 | 23.6 | 1.04 | 0.95 to 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.00 to 1.21 | |

| No. of comorbidities | .021 | ||||||||

| 1-5 | 6,334 | 76.5 | 1,948 | 23.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| ≥ 6 | 1,495 | 74.0 | 525 | 26.0 | 0.88 | 0.78 to 0.98 | 0.88 | 0.79 to 0.99 | |

| Physician specialty | .867 | ||||||||

| Hematology-oncology | 5,612 | 75.9 | 1,777 | 24.1 | 0.99 | 0.90 to 1.10 | — | ||

| Other | 2,217 | 76.1 | 696 | 23.9 | 1.0 | — | |||

Abbreviations: HT, hormonal therapy; OR, odds ratio.

χ2 statistical comparison across total distribution of selected characteristics.

Fig 1.

Racial difference in adherence to hormonal therapy within each net worth category.

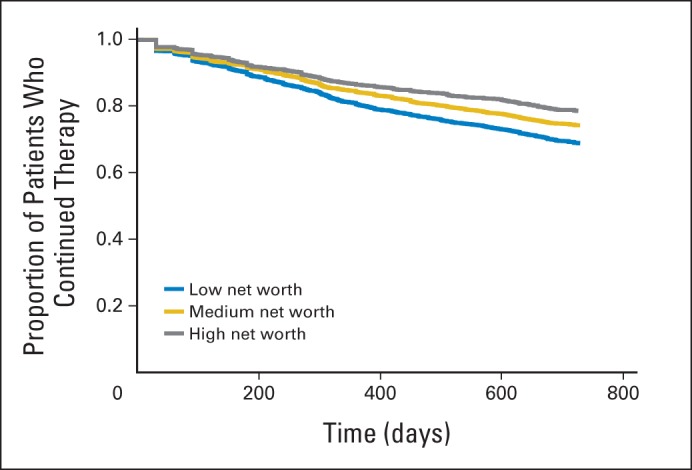

Early discontinuation was identified in 2,652 women (26%). In the multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis, discontinuation was negatively associated with a medium net worth (hazard ratio [HR], 0.82; 95% CI, 0.76 to 0.90) and high net worth (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.59 to 0.75) compared with low net worth. The association between black race and discontinuation was diminished in the multivariable analysis (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.14) compared with the unadjusted association (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.32). Women with more comorbid conditions (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.22) and those age 50 to 55 years (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.22) were more likely to discontinue therapy early (Appendix Table A1, online only). Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves showed differences in discontinuation by net worth over time (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for continuation of hormonal therapy by net worth category (P < .01).

A series of multivariable models showing the relationship between race and adherence are listed in Table 3. In the unadjusted model, the odds of being adherent to hormonal therapy for black women were 32% lower than for white women (OR, 0.76; P < .001). After adjustment for net worth, the odds of being adherent for black women were now 19% lower (OR, 0.84; P = .02). The addition of further clinical, financial, and sociodemographic variables had only a slight additional effect on the relationship between black race and adherence In the full model, the racial disparity was reduced (OR, 0.87; P = .08). The analysis showed similar results with income substituted for net worth (Appendix Table A2, online only). A sensitivity analysis was performed categorizing net worth as a continuous variable, and the results were unchanged.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Examining Effect of Demographic and Net Worth on Race Disparities in Adherence to Hormonal Therapy

| Multivariable Model | Analysis Comparing Blacks to Whites |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black |

||

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Race | Referent | 0.76* | 0.65 to 0.88 |

| Race + net worth | — | 0.84* | 0.72 to 0.98 |

| Race + net worth + copay | — | 0.84* | 0.72 to 0.98 |

| Race + net worth + copay + comorbidities | — | 0.84* | 0.72 to 0.98 |

| Full model† | — | 0.87‡ | 0.74 to 1.01 |

P < .01.

Full model = race + net worth + copay + comorbidities + Medicare + region + education + age + year of hormonal therapy + comorbidities + mastectomy.

P = .08.

DISCUSSION

In this study of women with BC whose pharmacy benefits were administered through a large US health plan manager, we found that financial factors, such as income and net worth, were linearly associated with adherence and discontinuation to hormonal therapy. We also found that black race was associated with decreased hormonal therapy adherence and increased discontinuation. Interestingly, the association between race and adherence is reduced after controlling for net worth, and in a stratified analysis, the racial difference was only observed in hormone therapy adherence in the low net worth group; no racial disparity is observed in the medium and high net worth groups.

It is increasingly recognized that the financial burden from health care costs results in significant patient distress, and as a result, increased attention has been paid to the financial toxicity of oncologic treatments.32 In a population-based study in patients with colorectal cancer, 38% of patients reported at least one treatment-related financial hardship, defined as debt accumulation, borrowing money from family or friends, ≥ 20% income decline, or selling/refinancing the primary home.33 Patients with cancer are more than twice as likely to file for bankruptcy than people without cancer, and younger patients with cancer are up to five times more likely to file for bankruptcy than patients with cancer ≥ age 65 years.34 Survivors of cancer who report financial problems are also more likely to report delaying medical care or foregoing medical care and prescriptions.35,36 It is not surprising that patients who are more financially vulnerable are more likely to discontinue therapy early or delay renewing prescriptions. Other investigators have previously evaluated the association between financial factors and medication adherence. In a study that used the 5% Medicare random sample, Medicare beneficiaries had reduced adherence to heart failure and diabetes medications during the drug coverage gap. Patients on generic drugs had greater adherence during the coverage gap than those on brand name drugs.37 Similarly, significant reductions in the MPR for β-blockers, statins, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have been reported during the Medicare coverage gap.38

We found that household net worth was a significant contributor to racial disparities in hormonal therapy adherence. We also found that it was a better predictor of adherence than insurance. This is likely a result of the fact that the correlation between wealth and income decreases after retirement. Others have observed an association between net worth (wealth) and various health states, but none have focused on cancer or cancer therapy. For example, wealth is associated with higher mammographic screening rates, less self-related health, and decreased symptom burden at the end of life.28,39,40 In addition, a systematic review of 29 studies that evaluated wealth and health summarized that personal wealth was associated with lower mortality, lower prevalence of chronic medical conditions, improved functional status, and reduced health care utilization.41 Importantly, controlling for wealth (net worth) reduced or eliminated observed racial differences in health.41 In aggregate, these findings suggest that measures of socioeconomic status may not be sufficient when measuring factors that contribute to racial disparities if they do not account for personal wealth.

As with our prior analysis,20 in an unadjusted analysis, women in the highest income bracket were significantly more likely to be adherent than women in the lowest income group. However, when net worth was added to the model, this association was no longer significant. Low-income groups have traditionally been found to be vulnerable with regard to quality of health care, and this may be exacerbated by the overlap in the time frame of this study with the economic downturn in the United States. However, income may be an inadequate assessment of financial resources. This is particularly true for the elderly, for whom net worth seems to be a more accurate metric of socioeconomic differences in use of health care services.42

Although we have focused on adherence to hormonal therapy in this article, which represents the largest population of patients with cancer taking oral antineoplastic agents, there are also concerns about nonadherence with imatinib in chronic myelogenous leukemia,43–45 thiopurine in pediatric leukemia,46 and capecitabine in breast and GI tract cancers.47 This issue will become increasingly important as more oral antineoplastic drugs come into use.48 The average total monthly cost of oral biologic therapies ranges from $5,000 to $8,000, whereas AIs cost between $180 and $400 per month. Higher drug costs will likely translate to higher out-of-pocket costs. Patients with fewer financial resources or less comprehensive health insurance may be most vulnerable.

This study had several strengths. We used a large database with a nationwide sample that included patients with a wide variety of prescription benefit plans, allowing for a population with diverse financial backgrounds. This study independently evaluated the effects of income, net worth, and copayment amount. There has been minimal prior work evaluating these financial factors in patients with cancer, particularly in combination. However, some study limitations should be mentioned. All of our patients received some form of prescription coverage, and therefore, our results are not generalizable to patients without prescription coverage. Along the same lines, all of the patients in our sample had commercial insurance and, therefore, may represent a relatively wealthy population. Mail-order pharmacies may underestimate the true adherence rate, because some patients have automatic refill services. We did not have individual information on why patients discontinued therapy, which, in some cases, may have been because of toxicity or patient preference. Finally, our measure of net worth is estimated based on a composite of public records, purchase transactions, census data, and consumer surveys. It is possible that this algorithm may not account for all household assets.

In summary, we have shown that household net worth is associated with adherence and discontinuation of adjuvant hormonal therapy and partially explains the observed racial disparities in hormonal therapy adherence and discontinuation. These results suggest that economic factors may contribute significantly to disparities in the quality of BC care. Future studies evaluating disparities in BC care and survival outcome should account for individual-level economic factors, such as income, and global financial resources, such as net worth. Interventions to reduce racial disparities in adherence should target individuals with low net worth.

Appendix

Table A1.

HT Discontinuation in Women With Localized Breast Cancer

| Factor | No Discontinuation (n = 7,650) |

Discontinued (n = 2,652) |

Unadjusted Analysis |

Multivariable Analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 6,090 | 74.7 | 1,911 | 25.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Black | 673 | 70.7 | 274 | 29.3 | 1.16 | 1.02 to 1.32 | 1.04 | 0.91 to 1.14 |

| Hispanic | 431 | 72.4 | 164 | 27.6 | 1.21 | 0.94 to 1.57 | 1.09 | 0.84 to 1.42 |

| Asian | 169 | 76.1 | 53 | 23.9 | 1.01 | 0.72 to 1.42 | 0.95 | 0.68 to 1.34 |

| Other | 28 | 71.8 | 11 | 28.2 | 0.95 | 0.77 to 1.18 | 0.97 | 0.79 to 1.21 |

| Region | ||||||||

| Northeast | 801 | 78.6 | 188 | 18.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| West | 1,343 | 72.4 | 512 | 27.6 | 1.26 | 1.07 to 1.47 | 1.27 | 1.09 to 1.50 |

| Midwest | 1,970 | 77.3 | 579 | 22.7 | 1.07 | 0.91 to 1.24 | 1.04 | 0.89 to 1.22 |

| South | 3,531 | 72.5 | 4,871 | 27.5 | 1.27 | 1.10 to 1.46 | 1.22 | 1.06 to 1.42 |

| Net worth | ||||||||

| Low (< $250,000) | 2,391 | 70.6 | 958 | 28.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Medium ($250,000-$750,000) | 3,839 | 74.9 | 1,143 | 25.1 | 0.80 | 0.74 to 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.76 to 0.90 |

| High (> $750,000) | 1,525 | 78.8 | 410 | 21.2 | 0.65 | 0.58 to 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.59 to 0.75 |

| Household income | ||||||||

| Low (< $40,000) | 1,539 | 72.3 | 590 | 27.7 | 1.0 | — | ||

| Medium ($40,000-$100,000) | 4,301 | 74.0 | 1,511 | 26.0 | 0.94 | 0.86 to 1.04 | — | |

| High (> $100,000) | 1,810 | 76.7 | 551 | 23.3 | 0.81 | 0.72 to 0.91 | — | |

| Adjusted 30-day copay | ||||||||

| < $10 | 2,491 | 75.1 | 824 | 24.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| $10-$20 | 2,276 | 75.7 | 730 | 24.3 | 0.96 | 0.86 to 1.06 | 0.96 | 0.86 to 1.06 |

| > $20 | 2,883 | 72.4 | 1,098 | 27.6 | 1.03 | 0.94 to 1.13 | 1.06 | 0.96 to 1.17 |

| Medicare | ||||||||

| No | 7,363 | 74.6 | 2,504 | 25.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 287 | 66.0 | 148 | 34.0 | 1.17 | 0.99 to 1.38 | 1.08 | 0.89 to 1.30 |

| Education | ||||||||

| < High school | 2,049 | 72.6 | 775 | 27.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| > High school | 5,601 | 74.9 | 1,877 | 25.1 | 0.90 | 0.82 to 0.97 | 1.04 | 0.94 to 1.14 |

| Age at HT initiation, years | ||||||||

| 50-55 | 2,165 | 72.5 | 821 | 27.5 | 1.16 | 1.06 to 1.27 | 1.14 | 1.05 to 1.22 |

| 56-65 | 3,970 | 76.2 | 1,243 | 23.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 66-75 | 1,042 | 74.5 | 356 | 25.5 | 0.98 | 0.87 to 1.10 | 0.95 | 0.84 to 1.08 |

| ≥ 75 | 473 | 67.1 | 232 | 32.9 | 1.20 | 1.05 to 1.39 | 1.16 | 0.99 to 1.35 |

| Year of HT initiation | ||||||||

| 2007 | 1,045 | 70.1 | 445 | 29.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 2008 | 1,836 | 69.1 | 821 | 30.9 | 1.07 | 0.95 to 1.20 | 1.05 | 0.94 to 1.18 |

| 2009 | 1,959 | 73.8 | 696 | 26.2 | 1.08 | 0.95 to 1.22 | 1.08 | 0.95 to 1.22 |

| 2010 | 1,975 | 79.4 | 512 | 20.6 | 1.08 | 0.94 to 1.22 | 1.08 | 0.95 to 1.24 |

| 2011 | 835 | 82.4 | 178 | 17.6 | 1.47 | 1.23 to 1.76 | 1.51 | 1.26 to 1.82 |

| Mastectomy | ||||||||

| No | 3,806 | 74.2 | 1,322 | 25.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 3,844 | 74.3 | 1,330 | 25.7 | 0.99 | 0.91 to 1.06 | 0.96 | 0.89 to 1.04 |

| No. of comorbidities | ||||||||

| 1-5 | 6,177 | 74.6 | 2,105 | 25.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| ≥ 6 | 1,473 | 72.9 | 547 | 27.1 | 1.12 | 1.02 to 1.24 | 1.11 | 1.01 to 1.22 |

| Physician specialty | ||||||||

| Hematology-Oncology | 5,498 | 74.4 | 1,891 | 25.6 | 0.97 | 0.89 to 1.05 | — | |

| Other | 2,152 | 73.9 | 761 | 26.1 | 1.0 | — | ||

Abbreviations: HT, hormonal therapy; HR, hazard ratio.

Table A2.

Logistic Regression Examining Effect of Demographic and Income on Race Disparities in Adherence to Hormonal Therapy

| Multivariable Model | Analysis Comparing Blacks to Whites |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black |

||

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Race | Referent | 0.76* | 0.65 to 0.88 |

| Race + income | — | 0.81* | 0.70 to 0.96 |

| Race + income + copay | — | 0.81* | 0.70 to 0.95 |

| Race + income + copay + comorbidities | — | 0.82* | 0.70 to 0.95 |

| Full model† | — | 0.85‡ | 0.73 to 1.00 |

P < .01.

Full model = race + income + copay + comorbidities + Medicare + region + education + age + year of hormonal therapy + comorbidities + mastectomy.

P = .04.

Footnotes

Supported by Grant No. RSGT-11-012-01-CPHPS from the American Cancer Society (A.I.N.), a fellowship from the National Cancer Institute (Grant No. R25 CA094061; J.T.), and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (D.L.H.).

None of the funders have participated in the conduct of this study.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Dawn L. Hershman, Jennifer Tsui, Jason D. Wright, Alfred I. Neugut

Financial support: Dawn L. Hershman, Alfred I. Neugut

Administrative support: Dawn L. Hershman

Collection and assembly of data: Dawn L. Hershman

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Household Net Worth, Racial Disparities, and Hormonal Therapy Adherence Among Women With Early-Stage Breast Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Dawn L. Hershman

No relationship to disclose

Jennifer Tsui

No relationship to disclose

Jason D. Wright

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst)

Ellie J. Coromilis

No relationship to disclose

Wei Yann Tsai

No relationship to disclose

Alfred I. Neugut

Consulting or Advisory Role: Executive Health Exams, Intl, Pfizer

REFERENCES

- 1.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD000011. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banning M. A review of interventions used to improve adherence to medication in older people. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Cooper PS, et al. Interventions to improve medication adherence among older adults: Meta-analysis of adherence outcomes among randomized controlled trials. Gerontologist. 2009;49:447–462. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visvanathan K, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Use of pharmacologic interventions for breast cancer risk reduction: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2942–2962. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimmick G, Anderson R, Camacho F, et al. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3445–3451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziller V, Kalder M, Albert US, et al. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:431–436. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, et al. Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:556–562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chlebowski RT, Geller ML. Adherence to endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Oncology. 2006;71:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000100444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lash TL, Fox MP, Westrup JL, et al. Adherence to tamoxifen over the five-year course. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99:215–220. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, et al. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:602–606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan PT, et al. Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1763–1768. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swedish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. Randomized trial of two versus five years of adjuvant tamoxifen for postmenopausal early stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1543–1549. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.21.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yood MU, Owusu C, Buist DS, et al. Mortality impact of less-than-standard therapy in older breast cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryant J, Fisher B, Dignam J. Duration of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001;30:56–61. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fink AK, Gurwitz J, Rakowski W, et al. Patient beliefs and tamoxifen discontinuance in older women with estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3309–3315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grunfeld EA, Hunter MS, Sikka P, et al. Adherence beliefs among breast cancer patients taking tamoxifen. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Clark AS, et al. Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2013;310:389–397. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2534–2542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hershman D, Tsui J, Meyer J, et al. Change from brand to generic aromatase inhibitors and hormone therapy adherence for early stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts and Figures, 2011-2012. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shavers VL, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:334–357. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassett MJ, Griggs JJ. Disparities in breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy: Moving beyond yes or no. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2120–2121. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, et al. Missed opportunities: Racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1357–1362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hershman DL, Wang X, McBride R, et al. Delay of adjuvant chemotherapy initiation following breast cancer surgery among elderly women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99:313–321. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9206-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hershman DL, Wang X, McBride R, et al. Delay in initiating adjuvant radiotherapy following breast conservation surgery and its impact on survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1353–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollack CE, Cubbin C, Sania A, et al. Do wealth disparities contribute to health disparities within racial/ethnic groups? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:439–445. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-200999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dang DK, Pont JM, Portnoy MA. Episode treatment groups: An illness classification and episode building system—Part I. Med Interface. 1996;9:118–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dang DK, Pont JM, Portmoy MA. Episode treatment groups: An illness classification and episode building system—Part II. Med Interface. 1996;9:122–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hess LM, Raebel MA, Conner DA, et al. Measurement of adherence in pharmacy administrative databases: A proposal for standard definitions and preferred measures. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1280–1288. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure: Out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1484–1486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1306826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, et al. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: A population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1608–1614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1143–1152. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119:3710–3717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, et al. Forgoing medical care because of cost: Assessing disparities in healthcare access among cancer survivors living in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116:3493–3504. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Baik SH, Lave JR. Effects of Medicare Part D coverage gap on medication adherence. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:e214–e224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stuart B, Davidoff A, Erten M, et al. How Medicare Part D benefit phases affect adherence with evidence-based medications following acute myocardial infarction. Health Serv Res. 2013;48:1960–1977. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams BA, Lindquist K, Sudore RL, et al. Screening mammography in older women: Effect of wealth and prognosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:514–520. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silveira MJ, Kabeto MU, Langa KM. Net worth predicts symptom burden at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:827–837. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollack CE, Chideya S, Cubbin C, et al. Should health studies measure wealth? A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allin S, Masseria C, Mossialos E. Measuring socioeconomic differences in use of health care services by wealth versus by income. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1849–1855. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noens L, van Lierde MA, De Bock R, et al. Prevalence, determinants, and outcomes of nonadherence to imatinib therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: The ADAGIO study. Blood. 2009;113:5401–5411. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darkow T, Henk HJ, Thomas SK, et al. Treatment interruptions and non-adherence with imatinib and associated healthcare costs: A retrospective analysis among managed care patients with chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25:481–496. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, et al. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:306–311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.9123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hawwa AF, Millership JS, Collier PS, et al. The development of an objective methodology to measure medication adherence to oral thiopurines in paediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: An exploratory study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:1105–1112. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0700-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Partridge AH, Archer L, Kornblith AB, et al. Adherence and persistence with oral adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer in CALGB 49907: Adherence companion study 60104. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2418–2422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruddy K, Mayer E, Partridge A. Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:56–66. doi: 10.3322/caac.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]