Summary

The recent discovery of combination-sensitive neurons in the primary auditory cortex of awake marmosets may reconcile previous, apparently contradictory, findings that cortical neurons produce strong, sustained responses, but also represent stimuli sparsely.

Recent advances in neural recording techniques have led to a debate over the most fundamental principles of representation in the primary auditory cortex (A1). As researchers increasingly study A1 in awake animals in preference to their long-established anesthetized preparations, conflicting claims have been made about the responsiveness of the neurons found there and their selectivity for particular sound features. A recent study [1] may help to reach a consensus on this matter, by showing that some A1 neurons respond vigorously to certain complex stimuli, even when responses to the elements of those stimuli are weak or nonexistent. This suggests that nonlinear mechanisms in auditory cortex can result in highly selective, ‘sparse’ responses, but that these responses can still be strong for ecologically relevant stimuli.

Responses in Auditory Cortex of Awake Animals: Sustained or Sparse?

It is often stated that neural responses in the cortex of awake, behaving animals are qualitatively different from those recorded under anesthesia. In anesthetized mammals, the responses of A1 neurons are generally dominated by a transient increase in firing rate that may not persist beyond the first few tens of milliseconds after a sound has begun. Such transient activity is consistent with responses observed in other sensory systems, but there is real doubt about the importance of these responses for neural coding. If the response stops shortly after the beginning of the sound, it is unclear how ongoing features of a sustained sound can be represented.

Some studies have shown that this is actually an oversimplification, as significant stimulus-related information can be found well after the end of the sound in the activity of A1 neurons recorded in anesthetized animals 2 and 3. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that sustained responses are more common in the awake animals than under anesthesia [4]. More intriguingly, Wang et al. [5] reported that such responses occur for particular sounds, and that different subsets of neurons produce sustained responses in response to different sounds. This suggests that acoustic stimuli are represented by prolonged increases in firing in varying subsets of neurons, questioning the significance of transient responses in the rest of the neural population.

However, these experiments used conventional extracellular recording methods. As Olshausen and Field [6] have argued, there is a potentially serious bias problem with this type of recording. Extracellular recording measures only action potentials or spiking activity. Thus, if a neuron produces no action potentials, it will not be detected. Even neurons that produce action potentials only occasionally will tend to be missed. This means that extracellular recordings will be biased towards those neurons that produce strong responses, and are therefore likely to overestimate the activity of the population.

To assess more accurately how different sounds are represented by the population of neurons in auditory cortex, Hromádka et al. [7] sequentially sampled the activity of A1 neurons in awake rats using cell-attached recordings. With the cell-attached technique, it is possible to know that the recording pipette is in contact with a neuron, even if the neuron does not produce any action potentials. This method therefore avoids the bias inherent in extracellular recording. Hromádka et al. [7] found that only a handful — less than 5% — of the neurons sampled produced well-driven responses to simple or naturalistic stimuli, while the majority of neurons failed to respond at all to any of these sounds.

Other studies have shown that, as well as being relatively rare events, individual action potentials can carry significant amounts of information. This has been demonstrated in mouse barrel cortex, for example, where optical activation of a small number of action potentials in a sparse subset of neurons can alter an animal’s behavior [8]. Thus, it would seem that perceptual decisions might be made on the basis of modest changes in firing rate by cortical neurons.

Theory of Sparse Coding

These two lines of evidence regarding the nature of the cortical representation appear to be in conflict. On the one hand, we have a view in which only sustained volleys of action potentials, generated by specific stimuli, matter. On the other, individual action potentials are thought to be significant and capable of determining an animal’s behavior.

To reconcile these two points of view, it is helpful to take a theoretical perspective. The notion of ‘sparse coding’ 9 and 10 stems from the viewpoint that action potentials should be relatively rare events. Such rarity is likely to be metabolically efficient — action potential production is a major part of cortical energy consumption [11] — and may produce redundancy-reducing neural codes that are particularly well-suited to natural sensory signals [12].

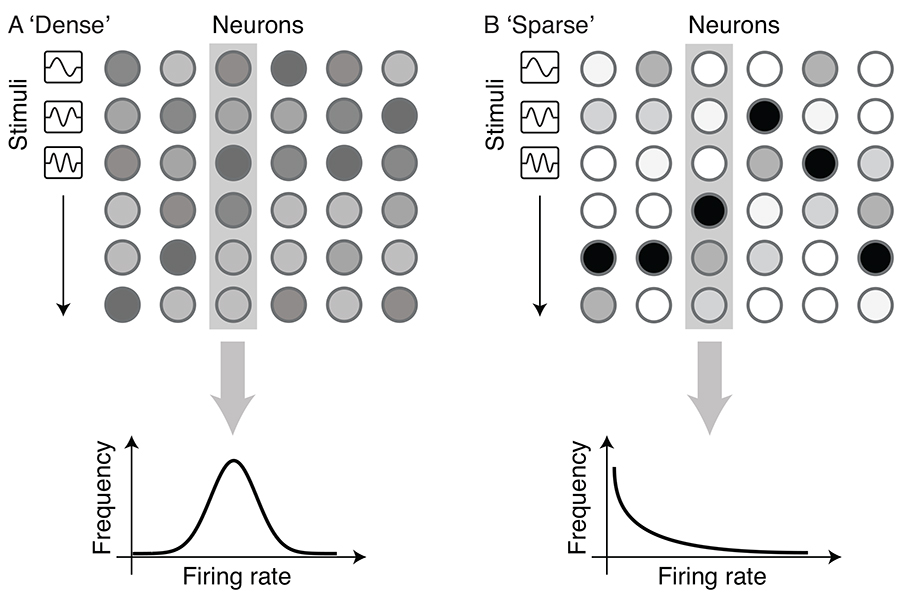

The visual cortex is believed to represent natural visual input using a sparse code 9 and 13, in which only a small proportion of neurons are active at any given time. Consequently, small subsets of the population participate in the representation of each stimulus, as shown in Figure 1. A sparse code is the opposite of a dense code, where a large proportion of neurons are active at all times, each contributing a small amount to the representation of each stimulus. Chechik et al. [14] have shown that redundancy is lower in A1 than in the thalamus; this is consistent with the idea that the auditory representation is sparser in the cortex than in subcortical structures.

Figure 1.

Sparse coding

(A) Neural codes are often assumed to be dense. In a dense code, a large proportion of neurons produce action potentials in response to every stimulus, and so activity (indicated by gray shading) is approximately evenly spread throughout the neural population. (B) In contrast, in a sparse code, a small, changing subset of neurons produces strong responses to each stimulus (black shading), whereas the rest of the population is quiescent or weakly active (white and pale shading). The resulting exponential response distribution of firing rate and the statistical independence between neurons reduce the redundancy of the neural code, while maximizing the information content of each action potential.

Sparse coding provides a clear theoretical account of the infrequent responses observed by Hromádka et al. [7]. But further investigation of the idea of sparse coding suggests that the strong responses observed in marmoset auditory cortex by Sadagopan and Wang [1] are also what should be expected from a sparse code. As shown in Figure 1, redundancy reduction and the maximization of information transmitted by each spike require neurons to have sparse, exponential response distributions — each neuron should produce disproportionately strong responses to a small proportion of stimuli. This is precisely the pattern of activity observed by Sadagopan and Wang [1].

Nonlinear Combination Sensitivity

The most important aspect of the study by Sadagopan and Wang [1] is that they present evidence which begins to reveal how the sparse responses in auditory cortex might arise. They show that many A1 neurons are sensitive to precise temporal and spectral combinations of tone pips, even though those neurons do not respond to the individual tone pips when presented alone. This suggests that A1 neurons are performing a highly nonlinear processing of sound; a standard linear model predicts that the neurons would respond weakly to each of the components of any complex sound that elicited a strong response.

Going back to the pioneering studies of Nobuo Suga and colleagues [15] in echolocating bats, combination sensitivity has long been known to be a property of neurons at higher levels of the auditory system. This is reminiscent of the conjunction-sensitive responses of neurons in area V4 of visual cortex. For example, Pasupathy and Connor [16] showed that V4 neurons are sensitive to both the elements and the position of visual boundary stimuli. This suggests that similar mechanisms of conjunction sensitivity operate in visual and auditory cortex, and also implies, as recently argued [17], that A1 might be more similar to higher visual areas than to primary visual cortex.

In both of these sensory systems, such highly nonlinear combination sensitivity presents a significant challenge to standard techniques for investigating neural responses to complex stimuli. Methods for characterizing such responses frequently assume (or test) a linear model relating the responses to the presented stimulus [18]. The linear model is powerful and tractable, and even when its assumptions are not precisely met, it can provide a reasonable description of neural processing [19]. As a result, the linear model continues to be the basis of many studies of sensory processing. Sadagopan and Wang [1] demonstrate a fundamental failure of the linear model: responses to combinations cannot be predicted from responses to the elements of those combinations. If, as seems highly probable, nonlinear combination sensitivity is an important mechanism in higher cortex, then understanding neurons in such areas will require the development of new classes of nonlinear models.

Another consequence of showing that A1 neurons can be highly selective for complex sounds is that this paves the way for investigating how these stimulus preferences are organized within the cortex. This is a controversial topic, but A1 clearly lacks the highly ordered organization that characterizes the primary cortical fields in other sensory modalities [17]. Indeed, one previous study [14] has demonstrated that neighboring A1 neurons can have quite different stimulus preferences. However, Sadagopan and Wang [1] note that nonlinear combination sensitivity is most prevalent in the superficial regions of the cortex, which is consistent with other recent evidence for laminar differences in the response properties of A1 neurons [20]. A more detailed investigation into the cortical location of these nonlinear interactions should help to reveal how this sparse representation of complex sounds arises, and provide further insights into the functional circuitry of A1.

References

- 1.Sadagopan S, Wang X. Nonlinear spectrotemporal interactions underlying selectivity for complex sounds in auditory cortex. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:11192–11202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1286-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moshitch D, Las L, Ulanovsky N, Bar-Yosef O, Nelken I. Responses of neurons in primary auditory cortex (A1) to pure tones in the halothane-anesthetized cat. J. Neurophysiol. 2006;95:3756–3769. doi: 10.1152/jn.00822.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell RAA, Schulz A, King AJ, Schnupp JWH. Brief sounds evoke prolonged responses in anesthetized ferret auditory cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2010 doi: 10.1152/jn.00730.2009. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu T, Liang L, Wang X. Temporal and rate representations of time-varying signals in the auditory cortex of awake primates. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:1131–1138. doi: 10.1038/nn737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Lu T, Snider RK, Liang L. Sustained firing in auditory cortex evoked by preferred stimuli. Nature. 2005;435:341–346. doi: 10.1038/nature03565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olshausen BA, Field DJ. How close are we to understanding V1? Neural Comput. 2005;17:1665–1699. doi: 10.1162/0899766054026639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hromádka T, DeWeese MR, Zador AM. Sparse representation of sounds in the unanesthetized auditory cortex. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huber D, Petreanu L, Ghitani N, Ranade S, Hromádka T, Mainen Z, Svoboda K. Sparse optical microstimulation in barrel cortex drives learned behaviour in freely moving mice. Nature. 2008;451:61–64. doi: 10.1038/nature06445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olshausen BA, Field DJ. Emergence of simple-cell receptive field properties by learning a sparse code for natural images. Nature. 1996;381:607–609. doi: 10.1038/381607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laughlin SB, Sejnowski TJ. Communication in neuronal networks. Science. 2003;301:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.1089662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1133–1145. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field DJ. What is the goal of sensory coding? Neural Computation. 1994;6:559–601. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinje WE, Gallant JL. Sparse coding and decorrelation in primary visual cortex during natural vision. Science. 2000;287:1273–1276. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chechik G, Anderson MJ, Bar-Yosef O, Young ED, Tishby N, Nelken I. Reduction of information redundancy in the ascending auditory pathway. Neuron. 2006;51:359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suga N. Principles of auditory information-processing derived from neuroethology. J. Exp. Biol. 1989;146:277–286. doi: 10.1242/jeb.146.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasupathy A, Connor CE. Shape representation in area V4: position-specific tuning for boundary conformation. J. Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2505–2519. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King AJ, Nelken I. Unraveling the principles of auditory cortical processing: can we learn from the visual system? Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:698–701. doi: 10.1038/nn.2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machens CK, Wehr MS, Zador AM. Linearity of cortical receptive fields measured with natural sounds. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:1089–1100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4445-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smyth D, Willmore B, Baker GE, Thompson ID, Tolhurst DJ. The receptive-field organization of simple cells in primary visual cortex of ferrets under natural scene stimulation. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:4746–4759. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04746.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atencio CA, Schreiner CE. Laminar diversity of dynamic sound processing in cat primary auditory cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2009 2009 Oct 28; doi: 10.1152/jn.00624.2009. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]