Abstract

AIM: To investigate whether there is a link between diabetes mellitus (DM) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

METHODS: We conducted a systematic search of PubMed and Web of Science databases, from their respective inceptions until December 31, 2013, for articles evaluating the relationship between DM and GERD. Studies were selected for analysis based on certain inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data were extracted from each study on the basis of predefined items. A meta-analysis was performed to compare the odds ratio (OR) in DM between individuals with and without GERD using a fixed effect or random effect model, depending on the absence or presence of significant heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were used to identify sources of heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed by Begg’s test. To evaluate the results, we also performed a sensitivity analysis.

RESULTS: When the electronic database and hand searches were combined, a total of nine eligible articles involving 9067 cases and 81 968 controls were included in our meta-analysis. Based on the random-effects model, these studies identified a significant association between DM and the risk of GERD (overall OR = 1.61; 95%CI: 1.36-1.91; P = 0.003). Subgroup analyses indicated that this result persisted in studies on populations from Eastern countries (OR = 1.71; 95%CI: 1.38-2.12; P = 0.003) and in younger patients (mean age < 50 years) (OR = 1.70; 95%CI: 1.22-2.37; P = 0.001). No significant publication bias was observed in this meta-analysis using Begg’s test (P = 0.175). The sensitivity analysis also confirmed the stability of our results.

CONCLUSION: This meta-analysis suggests that patients with DM are at greater risk of GERD than those who do not have DM.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Meta-analysis

Core tip: Based on a meta-analysis, we demonstrated that diabetes mellitus is associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Our findings suggested that this association was greater in patients aged < 50 years and in Asian populations.

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is characterized by the presence of esophageal mucosal injury or reflux symptoms caused by the abnormal reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus[1]. The symptoms include heartburn, acid regurgitation and non-cardiac chest pain. Serious esophageal complications of GERD include erosive esophagitis, esophageal stricture, Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Various conditions such as disturbance of the lower esophageal sphincter, increased gastric acid production, increased intragastric pressure and esophageal acid exposure are believed to play an important role in the development of GERD[2-4]. Our understanding of the mechanisms of this disease is incomplete. GERD was found to be highly prevalent in Western societies. However, GERD is a common disorder in both Western and Asian populations and has become more prevalent in Asian populations in recent decades. The disorder is important clinically not only for its influence on patients’ quality of life, but also for a significant proportion of the total cost it generates to the health care system.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the metabolic diseases characterized by hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action or both[5]. Patients with DM suffer various complications and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are frequently encountered in these patients. The pathogenesis of GI symptoms in DM, which are usually attributed to neurological impairment, especially autonomic neuropathy, have not been clearly elucidated. It is reported that esophageal dysfunction occurs frequently in patients with diabetic autonomic neuropathy[6] and esophageal transit is delayed in 35% of patients with DM[7].

Studies evaluating the relationship between DM and GERD have generated conflicting data. Some studies have indicated a positive association between either DM or the metabolic syndrome and GERD[8-10], while others have found no association between these conditions[11,12].

Given this uncertainty, we conducted a meta-analysis of available studies comparing the risk of GERD in individuals with and without DM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and search

We conducted a systematic search of PubMed and Web of Science databases from their inceptions until December 31, 2013. We used combinations of the subject headings: “diabetes mellitus”, “blood glucose”, “hyperglycemia”, “glycosylated hemoglobin”, “metabolic syndrome”, “gastroesophageal reflux”, “esophagitis”, “heartburn”, “esophageal pH” and “regurgitation”. We also performed hand searches in reference citations of identified reviews and original articles selected for full-text retrieval.

Study selection

For inclusion in the meta-analysis, a study had to fulfill the following criteria: (1) report the numbers of GERD and non-GERD subjects; (2) include data on individuals with and without DM in both GERD and non-GERD groups; and (3) be published in English. For overlapping studies, only the study with the largest sample numbers was included.

Definition of GERD

Although esophageal manometry and 24-h pH monitoring are the gold standards for detecting esophageal motor disorder and GERD, in our study, the diagnosis of GERD was established on the basis of reflux symptom questionnaires and the frequency of the cardinal symptoms, namely heartburn and acid regurgitation, occurring one or more times a week, with or without other symptoms.

The definition of esophagitis was established on the basis of endoscopic esophageal mucosal breaks.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Study selection was performed independently by two investigators (Sun and Tan). Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through consultation with the third reviewer (Zhu). We extracted the following data from each publication: the first author’s name, year of publication, country, proportion of men, number of GERD and control subjects and number of subjects with and without DM in both groups. The quality of each study was independently evaluated by each investigator using the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale[13].

Statistical analysis

Data from all relevant studies were combined to estimate the pooled OR with a 95%CI using a random effects model. Subgroup analyses according to geographic region and age were performed to assess the potential modifying effect of these variables on outcomes. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to investigate the influence of a single study on the overall risk estimate. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using I2 statistics; random effect models were used to determine when I2 was at least 50%. Publication bias was statistically assessed using Begg’s regression test. All analyses were conducted with STATA software version 12 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, United States). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study selection

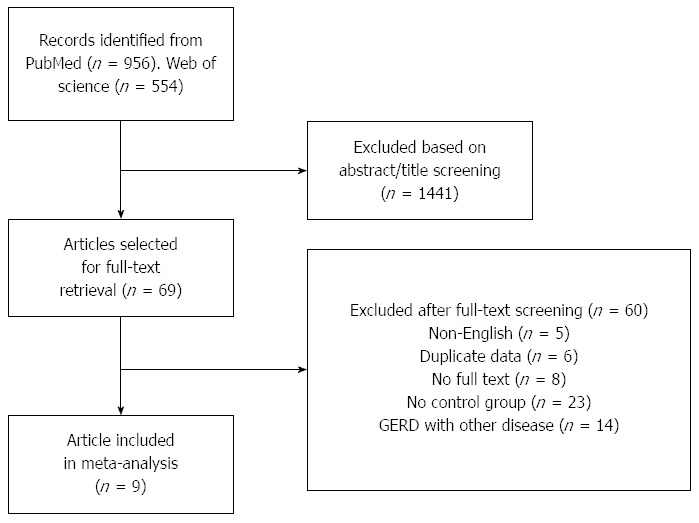

Our search of PubMed and Web of Science databases and manual review of articles cited in the identified and related publications initially retrieved 1510 articles, of which, 956 records were identified from the PubMed database and the remainder from Web of Science. After abstract and title screening, 1441 records were excluded as they were not related to our present meta-analysis. Of the 69 articles selected for detailed evaluation, the data of six studies were duplicated, 23 studies did not have a control group, five studies were not published in English, 14 articles evaluated the relationship between GERD and another disease, eight studies had no full-text and another four studies were excluded for having incomplete data. Overall, nine articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. A flow chart showing the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the selection process of the studies included in this meta-analysis. GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the nine included studies are summarized in Table 1. All studies were published in the past 10 years. Of these, one study was conducted in America, one in Europe and seven in Asia. Records from Japan[14], South Korea[15], Taiwan[16-18], Turkey[19] and China[20] were defined as Asian studies, while those from Europe[21] and America[22] were defined as Western studies. Of these nine studies, eight were cross-sectional and the other had a case-control design. Sample size ranged from 743 to 43 363 participants, with a total of 9067 individuals with GERD and 81 968 controls. Four studies evaluated the association between erosive esophagitis and DM[14-16,18]. None of the included records divided DM into Type 1 DM and Type 2 DM.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Ref. | Country | MeanAge (yr) | Men |

No. of subjects |

|||

| GERD (+) DM(+) | GERD (+) DM(-) | GERD (-) DM(+) | GERD (-) DM(-) | ||||

| Yönem et al[19] | Turkey | 42.57 | 50.7% | 42 | 217 | 90 | 996 |

| Kim et al[15] | South Korea | 46.7 | 59.0% | 119 | 1691 | 987 | 19167 |

| Chen et al[20] | China | 62.5 | 41.4% | 28 | 122 | 766 | 7134 |

| Tseng et al[17] | Taiwan | 52.3 | 56.9% | 248 | 2018 | 474 | 5030 |

| Jansson et al[21] | Sweden | 48.0 | 47.0% | 79 | 2744 | 847 | 35893 |

| Chiba et al[14] | Japan | 33.9 | 77.6% | 50 | 678 | 117 | 4145 |

| Rubenstein et al[22] | United States | 58.7 | 100.0% | 52 | 166 | 91 | 460 |

| Ou et al[16] | Taiwan | 51.4 | 58.6% | 60 | 292 | 188 | 1500 |

| Hsu et al[18] | Taiwan | 51.7 | 46.2% | 8 | 123 | 28 | 584 |

GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; DM: Diabetes mellitus.

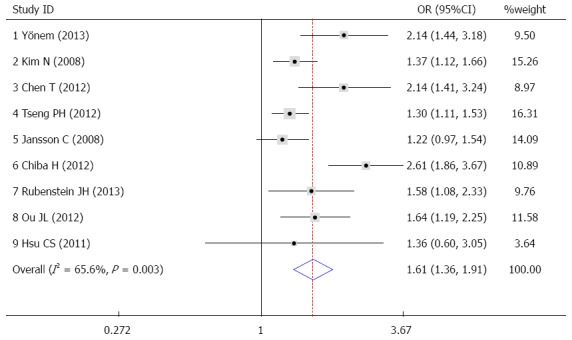

Main analysis of the prevalence of GERD associated with DM

None of the included studies divided DM into Type 1 DM and Type 2 DM. The OR was used to evaluate the association between DM and GERD. High heterogeneity was observed across the studies (I2 = 65.6%). Therefore, a random effects model was used. The overall pooled OR of DM in GERD subjects compared with that in non-GERD subjects was 1.61 (95%CI: 1.36-1.91; P = 0.003) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

OR and 95%CI of individual studies for the association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and diabetes mellitus in all subjects.

Subgroup meta-analysis

Many studies have found that the prevalence of GERD increases with age[23,24], presumably because aging decreases the motility of the esophagus. In order to explore the influence of age, we performed an age-stratified analysis, separating the studies into two subgroups with mean age < 50 years and mean age ≥ 50 years. We identified an association between DM and GERD in both subgroups and the OR was 1.70 (95%CI: 1.22-2.37) and 1.52 (95%CI: 1.27-1.82), respectively. However, only the subgroup with mean age < 50 years showed statistical significance (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

OR and 95%CI of individual studies for subgroup analysis by age (A) and by geographic region (B).

Figure 3B shows the results of subgroup analysis with reference to geographic region. A pooled analysis was conducted for the Asian and Western subgroups in order to explore the relationship between GERD patients and the risk of DM in different areas. The combined OR between GERD and DM in the Western studies was 1.33 (95%CI: 1.05-1.68). However, there was a more pronounced association in the Asian subgroup, OR = 1.71 (95%CI: 1.38-2.12).

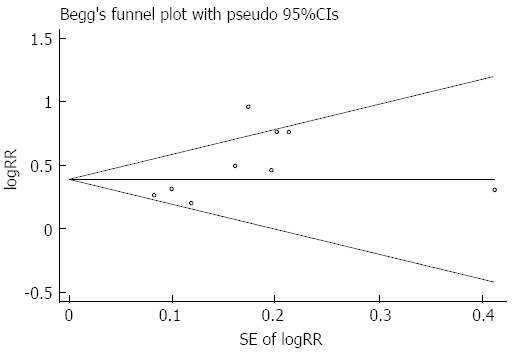

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

To test the robustness of our findings, sensitivity analysis was conducted. The analysis investigated the influence of a single study on the overall risk estimate by omitting one study at a time, yielding a narrow range of ORs from 1.48 (95%CI: 1.29-1.70) to 1.69 (95%CI: 1.38-2.06). In addition, no single study substantially contributed to the heterogeneity observed across all studies (Figure 4). Begg’s regression test revealed that there was no publication bias in the overall analysis (P = 0.175) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis.

Figure 5.

Begg’s regression for publication bias.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to explore the relationship between GERD and DM. Our results showed that DM was a significant risk factor for the prevalence of both GERD and esophagitis.

According to the Montreal definition[1], GERD is diagnosed when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications, such as reflux esophagitis, stricture, Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal adenocarcinoma, and the disease is subclassified into esophageal or extra-esophageal syndromes. The cardinal symptoms in GERD patients are heartburn and regurgitation[25]. GERD includes erosive esophagitis and endoscopy-negative reflux disease, which are also known as non-erosive reflux disease. It is reported that one of the reasons for the difficulty in identifying causative factors for GERD is the confusion between reflux esophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease[1]. Although the reflux of intragastric contents is defined as the etiology, the underlying mechanism of GERD has not been adequately elucidated. Multiple factors have been reported to be associated with GERD, such as age, gender, body mass index (BMI), body weight, alcohol consumption and smoking[26-29].

Patients with DM suffer various complications, among which esophageal dysfunction is common, including reduced amplitude of esophageal contractions, fewer peristaltic waves, a decrease in the velocity of peristalsis, reduced lower esophageal sphincter pressure and abnormal gastroesophageal reflux[30-32]. Abnormal gastroesophageal reflux, which is commonly named GERD, not only affects the quality of patients’ lives, but also increases the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma[33]. The major mechanism for GERD is transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. Classic studies have shown that being overweight and obesity are important independent risk factors for GERD. Obesity has been speculated to cause GERD symptoms due to multiple factors, including an increased gastroesophageal sphincter gradient, the incidence of hiatus hernia and intra-abdominal pressure[34]. Some patients with DM, particularly those with type 2 DM, are obese. This may be one reason why DM causes GERD. Although the pathophysiology of esophageal dysfunction in patients with DM is unknown, it has been suggested that this dysfunction is caused largely by autonomic neuropathy, especially vagal nerve damage[6], as most diabetic patients with esophageal dysfunction show evidence of coexistent peripheral motor or autonomic neuropathy. In addition, gastric emptying can be delayed by diabetic autonomic neuropathy, which may promote erosive esophagitis[35]. Various studies have reported on the relationship between diabetic autonomic neuropathy and esophageal dysfunction; however, no consensus has yet been reached. Diabetic neuropathy can develop at the time when blood glucose begins to increase but is usually seen 5-10 years after the onset of diabetes[36]. Patients with DM frequently have neuropathy without any gastrointestinal symptoms, which is attributed to simultaneous efferent and afferent nerve damage[37]. Consequently, an exact evaluation of esophageal dysfunction on the basis of symptoms may be difficult in patients with DM as typical reflux symptoms may be vague in some diabetic patients[38,39]. Previous studies indicated that the duration of DM is also an important factor for GI symptoms in type 2 DM patients as longer disease duration is associated with more complications[39,40]. It has been reported that diabetic patients with three major diabetic complications, retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy, are more likely to have symptomatic GERD[9]. Thus, maintaining a good HbA1c level and ideal body weight are important in preventing GERD in DM patients.

Our subgroup meta-analysis by geographic region showed that there was an association between GERD and DM in both the Asian or Western subgroup, while only the former showed statistical significance. GERD is known to be a major clinical problem in Western countries, with 14%-24% of adults experiencing heartburn and acid regurgitation at least once a week, and recently, the frequency has increased to approximately one-third of the adult population[41]. Unfortunately, GERD is becoming increasingly prevalent in Asia where it is currently estimated that more than 10% of the population experiences at least weekly symptoms of heartburn and/or acid regurgitation[26,42]. There appears to be racial differences in the clinical presentation as well as in the natural history of GERD between Eastern and Western societies[19]. Genetic factors, a high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, dietary differences and disparities in parietal cell mass and gastric acid secretion are possible factors accounting for these racial differences[43].

It is unclear whether the incidence and prevalence of GERD symptoms increase with age[27]. Some cross-sectional studies found no association, while other reports showed that the prevalence of erosive esophagitis increased with age[23,24]. The results of our study revealed that there was an association between age and GERD. The mechanisms responsible for the higher proportion of severe esophagitis in the elderly are unknown but it is assumed that impairment of esophageal motility in the elderly might be a factor. In addition, the presence of hiatus hernia is a risk factor for GERD in both the elderly and non-elderly and the incidence of hiatus hernia in the elderly is extremely high. Moreover, the mean size of hiatus hernia increases with advancing age[44]. A previous study also demonstrated that the size of hiatus hernia was associated with the severity of esophagitis[45].

In summary, we found a significant association between GERD and DM. Of course, a meta-analysis of observational studies in principle can never prove causality. The detailed mechanism underlying the relationship between DM and GERD should be studied as GERD in diabetic patients is clinically important as it may be associated with changes in the absorption of oral hypoglycemic drugs, for example. Moreover, the delayed transit of capsules and increased abnormal acid reflux may generate a risk of mucosal ulceration and decrease the patient’s quality of life. Consequently, early detection of GERD in patients with DM is very important so that adequate therapy can effectively delay the onset and slow the progression of such complications.

This study has a number of inherent limitations that warrant mentioning. Firstly, as most of the included studies were cross-sectional, only associations between DM and GERD could be determined, not cause and effect. To elucidate possible causal relationships, further studies with a longitudinal design and paired controls are required. Secondly, literature retrieval only included two databases and was restricted to English-language literature, so there may be a certain selection bias. Finally, the data were not adjusted for BMI.

COMMENTS

Background

Both diabetes mellitus (DM) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) have a high prevalence worldwide. The relationship between these diseases remains controversial.

Research frontiers

To date, several studies have assessed the association between DM and GERD in various regions and ethnic groups; however, the results have been mixed and inconsistent. No meta-analyses have been conducted on this topic.

Innovations and breakthroughs

When the electronic database and hand searches were combined, a total of nine observational studies were identified for final analysis, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The findings support an association between GERD and DM. However, the direction of this association remains to be determined.

Applications

DM appears to be either directly or indirectly associated with the risk of GERD. An exploration of the mechanism for this association may help to reduce GERD risk.

Peer-review

The authors show the association between DM and GERD by a meta-analysis. This manuscript is a well-described study of a current and relevant issue.

Footnotes

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: April 19, 2014

First decision: May 29, 2014

Article in press: August 28, 2014

P- Reviewer: Desai ND, Hillman LC, Rocha R S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R, Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920; quiz 1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB, Ergun GA, Pandolfino J, Fitzgerald S, Tran T, Kramer JR. Obesity increases oesophageal acid exposure. Gut. 2007;56:749–755. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.100263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JC, Mui LM, Cheung CM, Chan Y, Sung JJ. Obesity is associated with increased transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:883–889. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwakiri K, Sugiura T, Hayashi Y, Kotoyori M, Kawakami A, Makino H, Nomura T, Miyashita M, Takubo K, Sakamoto C. Esophageal motility in Japanese patients with Barrett’s esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1036–1041. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2013;36 Suppl 1:S67–S74. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verne GN, Sninsky CA. Diabetes and the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1998;27:861–874, vi-vii. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong MF, Horowitz M, Jones KL, Wishart JM, Harding PE. Natural history of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:503–507. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung SJ, Kim D, Park MJ, Kim YS, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Metabolic syndrome and visceral obesity as risk factors for reflux oesophagitis: a cross-sectional case-control study of 7078 Koreans undergoing health check-ups. Gut. 2008;57:1360–1365. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.147090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishida T, Tsuji S, Tsujii M, Arimitsu S, Sato T, Haruna Y, Miyamoto T, Kanda T, Kawano S, Hori M. Gastroesophageal reflux disease related to diabetes: Analysis of 241 cases with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:258–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horikawa A, Ishii-Nozawa R, Ohguro M, Takagi S, Ohtuji M, Yamada M, Kuzuya N, Ujihara N, Ujihara M, Takeuchi K. Prevalence of GORD (gastro-oesophageal reflux disease) in Type 2 diabetes and a comparison of clinical profiles between diabetic patients with and without GORD. Diabet Med. 2009;26:228–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ariizumi K, Koike T, Ohara S, Inomata Y, Abe Y, Iijima K, Imatani A, Oka T, Shimosegawa T. Incidence of reflux esophagitis and H pylori infection in diabetic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3212–3217. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kase H, Hattori Y, Sato N, Banba N, Kasai K. Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in diabetes patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;79:e6–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiba H, Gunji T, Sato H, Iijima K, Fujibayashi K, Okumura M, Sasabe N, Matsuhashi N, Nakajima A. A cross-sectional study on the risk factors for erosive esophagitis in young adults. Intern Med. 2012;51:1293–1299. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim N, Lee SW, Cho SI, Park CG, Yang CH, Kim HS, Rew JS, Moon JS, Kim S, Park SH, et al. pylori and Gerd Study Group of Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research. The prevalence of and risk factors for erosive oesophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease: a nationwide multicentre prospective study in Korea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:173–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ou JL, Tu CC, Hsu PI, Pan MH, Lee CC, Tsay FW, Wang HM, Cheng LC, Lai KH, Yu HC. Prevalence and risk factors of erosive esophagitis in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc. 2012;75:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tseng PH, Lee YC, Chiu HM, Chen CC, Liao WC, Tu CH, Yang WS, Wu MS. Association of diabetes and HbA1c levels with gastrointestinal manifestations. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1053–1060. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu CS, Wang PC, Chen JH, Su WC, Tseng TC, Chen HD, Hsiao TH, Wang CC, Lin HH, Shyu RY, et al. Increasing insulin resistance is associated with increased severity and prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:994–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yönem Ö, Sivri B, Özdemir L, Nadir I, Yüksel S, Uygun Y. Gastroesophageal reflux disease prevalence in the city of Sivas. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2013;24:303–310. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2013.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen T, Lu M, Wang X, Yang Y, Zhang J, Jin L, Ye W. Prevalence and risk factors of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in a Chinese retiree cohort. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Johnsen R, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Severe symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease are associated with cardiovascular disease and other gastrointestinal symptoms, but not diabetes: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubenstein JH, Morgenstern H, McConell D, Scheiman JM, Schoenfeld P, Appelman H, McMahon LF, Kao JY, Metko V, Zhang M, et al. Associations of diabetes mellitus, insulin, leptin, and ghrelin with gastroesophageal reflux and Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1237–1244.e1-e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson DA, Fennerty MB. Heartburn severity underestimates erosive esophagitis severity in elderly patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:660–664. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohammed I, Cherkas LF, Riley SA, Spector TD, Trudgill NJ. Genetic influences in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a twin study. Gut. 2003;52:1085–1089. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.8.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moraes-Filho JP, Navarro-Rodriguez T, Eisig JN, Barbuti RC, Chinzon D, Quigley EM. Comorbidities are frequent in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease in a tertiary health care hospital. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64:785–790. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000800013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–717. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moayyedi P, Talley NJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 2006;367:2086–2100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, Kelly CP, Camargo CA. Body-mass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2340–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng Z, Margolis KL, Liu S, Tinker LF, Ye W, Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Effects of estrogen with and without progestin and obesity on symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:72–81. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinekawa F, Kubo F, Matsuda K, Fujita Y, Tomita T, Uchida Y, Nishioka M. Relationship between esophageal dysfunction and neuropathy in diabetic patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2026–2032. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Annese V, Bassotti G, Caruso N, De Cosmo S, Gabbrielli A, Modoni S, Frusciante V, Andriulli A. Gastrointestinal motor dysfunction, symptoms, and neuropathy in noninsulin-dependent (type 2) diabetes mellitus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:171–177. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199909000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lluch I, Ascaso JF, Mora F, Minguez M, Peña A, Hernandez A, Benages A. Gastroesophageal reflux in diabetes mellitus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:919–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.987_j.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thrift AP, Pandeya N, Whiteman DC. Current status and future perspectives on the etiology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2012;2:11. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Vries DR, van Herwaarden MA, Smout AJ, Samsom M. Gastroesophageal pressure gradients in gastroesophageal reflux disease: relations with hiatal hernia, body mass index, and esophageal acid exposure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1349–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loke SS, Yang KD, Chen KD, Chen JF. Erosive esophagitis associated with metabolic syndrome, impaired liver function, and dyslipidemia. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5883–5888. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moki F, Kusano M, Mizuide M, Shimoyama Y, Kawamura O, Takagi H, Imai T, Mori M. Association between reflux oesophagitis and features of the metabolic syndrome in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1069–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frøkjaer JB, Andersen SD, Ejskaer N, Funch-Jensen P, Arendt-Nielsen L, Gregersen H, Drewes AM. Gut sensations in diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Pain. 2007;131:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kinekawa F, Kubo F, Matsuda K, Kobayashi M, Furuta Y, Yamanouchi H, Inoue H, Kurata H, Uchida Y, Kuriyama S. Is the questionnaire for the assessment of gastroesophageal reflux useful for diabetic patients? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1017–1020. doi: 10.1080/00365520500217043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kinekawa F, Kubo F, Matsuda K, Kobayashi M, Furuta Y, Fujita Y, Okada H, Muraoka T, Yamanouchi H, Inoue H, et al. Esophageal function worsens with long duration of diabetes. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:338–344. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bytzer P, Talley NJ, Leemon M, Young LJ, Jones MP, Horowitz M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with diabetes mellitus: a population-based survey of 15,000 adults. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1989–1996. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.16.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nocon M, Keil T, Willich SN. Prevalence and sociodemographics of reflux symptoms in Germany--results from a national survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1601–1605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goh KL. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: A historical perspective and present challenges. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 1:2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spechler SJ, Jain SK, Tendler DA, Parker RA. Racial differences in the frequency of symptoms and complications of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1795–1800. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Leandro G, Scarcelli C, D’Ambrosio LP, Seripa D, Perri F, Niro V, Paris F, Andriulli A, et al. Clinical features of reflux esophagitis in older people: a study of 840 consecutive patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1537–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones MP, Sloan SS, Rabine JC, Ebert CC, Huang CF, Kahrilas PJ. Hiatal hernia size is the dominant determinant of esophagitis presence and severity in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1711–1717. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]